Introduction

Introduction

No community in Yemen has suffered the consequences of the current war as harshly as the Muhamasheen (Marginalized), a Yemeni underclass that has experienced centuries of discrimination, exploitation and poverty. The Muhamasheen (sing. Muhamash) are commonly referred to in Yemen as the Akhdam (servants). While there are no official statistics on the size of the community, the UN has reported that there are up to 3.5 million Muhamasheen in Yemen.[1]

Prior to the current conflict, social discrimination against the Muhamasheen limited their access to education, healthcare, housing and meaningful work. As this policy brief explores, the war has compounded these vulnerabilities and the existing poverty of this group. Discrimination against the Muhamasheen has also hindered their access to humanitarian aid and made it harder for those who have been displaced by fighting to find safe shelter.

For several months this author has been conducting interviews with Muhamasheen from across Yemen about how the conflict has affected them. This policy brief presents the outcomes of these conversations, as well as recommendations to address the multi-faceted challenges this community faces.

Disputed Origins at the Core of Social Marginalization

The origins of Yemen’s Muhamasheen community are disputed. A popular belief is that the Muhamasheen are descendants of Abyssinian soldiers who occupied Yemen in the sixth century.[2] Another account traces their origins to Yemen’s Red Sea coastal plain.[3] Nuaman al-Hudhaifi, president of the National Union for the Marginalized, says the community’s marginalization stems from the overthrow and enslavement of the Najahid dynasty in the 12th century.

In a society where the social structure is partly based on lineage, the Muhamasheen’s unclear origins and existence outside tribal structures has led to centuries of descent-based discrimination. While the Hashemites, who are said to be descended from Prophet Mohammad, are at the top of Yemen’s social hierarchy in many areas of the country, the Muhamasheen — considered without origin — occupy the bottom regardless of where they live.[4] This also intersects with racial discrimination, as most Muhamasheen are dark-skinned.

The Contours of Community Exploitation and Discrimination

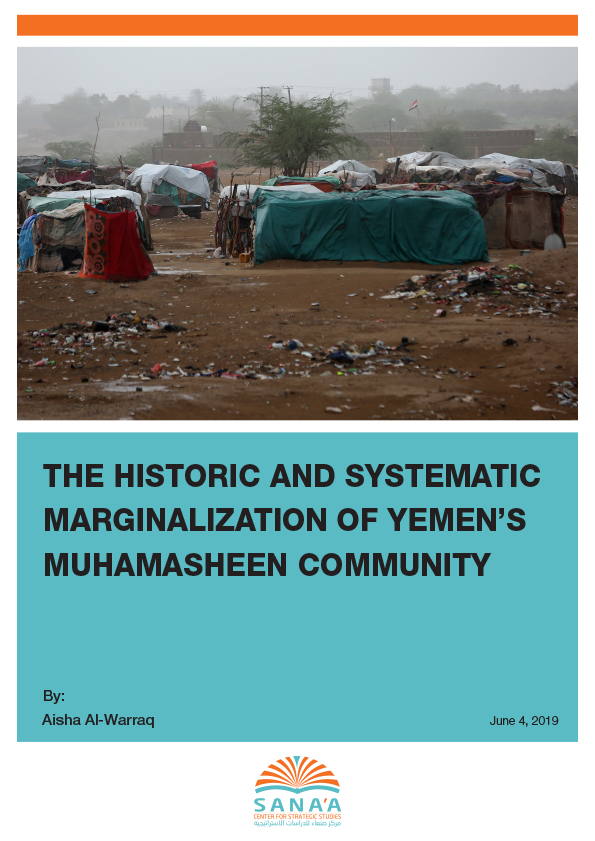

Today, discrimination against Yemen’s Muhamasheen manifests in multiple ways, blending elements of both racism and a caste system. The minority group mostly resides in slums on the outskirts of cities, often without electricity, clean water or secure shelters. Low school enrollment levels have resulted in literacy levels of 20 percent among adults, according to a study by UNICEF.[5] Muhamasheen children often face harassment and bullying by teachers and other students at school, leading to high drop-out rates, while Muhamasheen parents sometimes withdraw their children from school so they can work.[6] According to UNICEF, just nine percent of Muhamasheen register their children at birth, and the lack of birth certificates can also be an obstacle to school enrollment.[7]

Al-Hudhaifi said that he faced less harassment at school than other Muhamasheen children in part due to his skills as a football player, which won him a place on the school football team. Al-Hudhaifi now works for the Ministry of Public Works and Roads in Taiz. In general, however, Muhamasheen are excluded from public sector jobs, except in waste management as street cleaners, where they work on daily wages and without employment contracts. In the private sector, they are typically confined to low-paid, socially-stigmatized work such as shoe-shining, car washing and collecting plastic and scrap material.

There are large Muhamasheen communities in the governorates of Hudaydah, Taiz, Ibb, Lahj, Mahweet and the coastal areas of Hajjah and Hadramawt, though the group is present in every governorate in Yemen. Discrimination is generally worse in rural areas, where Muhamasheen are often prohibited from buying land or property, according to al-Hudhaifi. Some Muhamasheen are forced to work for local tribal or village leaders, or they cultivate land for agricultural use and pay the landowners from their yield in a sharecropping-type arrangement.

No Yemeni law specifically discriminates against the Muhamasheen, yet systemic discrimination prevents Muhamasheen from accessing redress or mediation from exploitation; they face systemic prejudice in the justice system and within local governments and tribal authorities.[8]

Muhamasheen at the National Dialogue Conference

Many in the Muhamasheen community took part in the Yemeni uprising of 2011, but while the revolution eventually forced President Ali Abdullah Saleh to step down, it did little to break down discrimination against this minority. Protesters from the Muhamasheen said they faced racism and discrimination inside Change Square, the central gathering place for those participating in the uprising in Sana’a.[9] In 2012, the first ever Muhamasheen conference was held in Sana’a, but al-Hudaifi said the Muhamasheen’s vision to resolve the community’s problems was ignored by the Technical Committee for the National Dialogue Conference (NDC), which was intended to guide Yemen’s post-revolutionary political transition. The National Union of the Marginalized, which was founded in 2007 and brings together 80 civil society organizations focused on the Muhamasheen, organized rallies in January 2013 in Taiz, Ibb, al-Bayda, Aden and in front of President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi’s residence in Sana’a demanding a place at the NDC, after which the Muhamasheen were promised fair representation on the committee. Ultimately, this did not materialize; al-Hudaifi was the sole representative of the Muhamasheen on the 565-member NDC committee.

Despite this, al-Hudaifi said the cause of the Muhamasheen garnered attention and sympathy at the NDC. The NDC outcomes included several recommendations to improve the inclusion and status of Muhamasheen in Yemeni society.[10] The NDC recommended that legislation should be enacted to ensure the full integration of the Muhamasheen, and their enjoyment of all the rights guaranteed by the Yemeni constitution. The NDC called specifically for legislation to ensure that the Muhamasheen achieved social equality and equal opportunities, and for moral, financial and legislative support to enable the Muhamasheen to participate in the development process. Other NDC recommendations addressed improving the participation of Muhamasheen in public life, proposing a 10 percent quota for the group in public sector employment and equal access to leadership and decision-making positions.[11]

The NDC outcomes were intended to guide Yemen’s new constitution. However, while the draft constitution released in January 2015 included articles enshrining the minimum political participation of women and youth, at 30 percent and 20 percent respectively, no such quota was included for the Muhamasheen.[12] The draft constitution contained one article calling for legislative and executive actions “to raise the status of vulnerable and marginalized groups,” to promote their political, economic and social participation, and to integrate them into society. Al-Hudaifi said the failure to incorporate NDC recommendations on the Muhamasheen in the draft constitution, in particular the absence of a quota, represented “a disavowal by all national forces” of the legal rights agreed by the NDC.

The Disproportionate Impact of the War on the Muhamasheen

The escalation of the ongoing conflict in March 2015 has greatly magnified the Muhamasheen community’s poverty, displacement and food insecurity. Although humanitarian agencies often feature the Muhamasheen in fundraising and publicity photographs documenting the Yemeni crisis, humanitarian aid to the community is far less consistent than for other groups, and in some areas the Muhamasheen have been systematically excluded from assistance.

The widespread economic collapse and loss of livelihoods driven by the conflict — between the armed Houthi movement and supporters of the internationally recognized Yemeni government — has created competition for the low-paid jobs which were once reserved for the Muhamasheen. Prior to the conflict the government’s Cleaning and Improvement Fund, which is responsible for waste management, was primarily staffed by Muhamasheen. However, garbage collectors were among the public sector workers who lost their income due to the conflict. UN agencies and other donors have stepped in to finance the Cleaning and Improvement Fund, creating livelihoods opportunities, but some Muhamasheen told the Sana’a Center that they have not benefited from these jobs, which have been taken instead by internally displaced people (IDPs) and others in need from outside the Muhamasheen community.

The Muhamasheen were among the first to be displaced in the current conflict, with the dislocation compounded by discrimination. Large communities of Muhamasheen were displaced by conflict in Aden, Taiz and Hudaydah, but have struggled to access IDP camps or shelter in public institutions, such as schools, due to prejudice from other IDPs.[13] Without tribal connections, the Muhamasheen also lack native villages to flee to. Instead, many displaced Muhamasheen who escaped frontlines have been forced to shelter in farmland, parks and public spaces, where it is difficult to access services or support. They have often been excluded from efforts by host communities and local authorities to support IDPs, and have been evicted from land where they have taken refuge.[14] For example, Muhamasheen families who fled from Saada to Amran were asked to leave agricultural land by landowners.[15] Their repeated displacement has pushed some Muhamasheen to the edges of cities and in some cases close to frontlines, increasing their vulnerability.[16]

Several other aspects of the conflict that have affected Yemenis across the country have been felt most acutely by Muhamasheen. Women and girls from the Muhamasheen have long faced a greater risk of gender-based violence than other women; during the conflict, Muhamasheen women have been more vulnerable than others to sexual violence and harassment by fighters, particularly at checkpoints.[17]

While access to healthcare in Yemen was precarious even before the current war began, the collapse of state institutions has made access far more difficult in many areas around the country. However, even where healthcare services are available, for Muhamasheen, treatment is at times denied due to discrimination; Muhamasheen, who have suffered injuries inflicted by both Houthi and anti-Houthi forces, have reported being denied treatment upon arrival at healthcare facilities.[18]

Different Areas, Similar Stories: Snapshots of the Muhamasheen Experience from Around Yemen

Bajel, Hudaydah Governorate

In Bajel district, northeast of Hudaydah City, an aid worker for an international humanitarian organization told the Sana’a Center that the Muhamasheen were rarely included on beneficiary lists. He supervises a cash-for-work project with the Cleaning and Improvement Fund which does not include any Muhamasheen beneficiaries, even though the community is disproportionately unemployed and lacking access to basic necessities in the district. The Muhamasheen’s lack of social or political power means they also lack representatives to lobby local community leaders for their inclusion, he said. Meanwhile, a supervisor for the Cleaning and Improvement Fund in Bajel said he was punished and nearly fired by his manager when he included Muhamasheen on a list of proposed beneficiaries to an international organization. His manager was under pressure from community leaders, district officials and local Houthi authorities, who insisted on vetting the list of names proposed as beneficiaries, he said.

A Muhamash who did secure work with the Cleaning and Improvement Fund in Bajel said he tried to advocate for more people from his neighborhood, al-Dhalam, to be given work through the program. Al-Dhalam is populated by Muhamasheen, most of whom live in tents without sanitation or water. He asked a local committee member, who identifies local beneficiaries for international humanitarian organizations, to include Muhamasheen from al-Dhalam as workers on the cleaning project and as beneficiaries of shelter and sanitation projects; the committee member refused and told him “these people are like cows.” While some Muhamasheen in the area do receive sporadic monthly food baskets, the aid is inconsistent and rations are often shared with families who have not been able to register, he added.

A teacher in al-Mahaniah in Bajel district told the Sana’a Center that many Muhamasheen had fled to the area to escape frontlines; they moved into existing Muhamasheen communities, which already lacked proper sanitation, contributing to increased cases of cholera.

Qataba District, al-Dhalea Governorate

In Qataba district in the northwest of al-Dhalea governorate, which is currently the site of heavy clashes between forces from the armed Houthi movement and the Saudi-led military coalition, locals told the Sana’a Center that more than 2,000 Muhamasheen families are living in precarious conditions under the constant threat of eviction by landowners. Some families live in one-room stone shelters, while others reside in tin shacks without protection from the sun in summer or insulation from the cold in winter. A Muhamash living in Qataba said the minority faced intense racism; he said that in May 2017, dozens of Muhamasheen were forcibly expelled from Qataba because a man from a local tribe intended to marry a woman from the Muhamasheen, contravening social norms. In retaliation, the man was killed by his brother and members of his tribe burned down the homes of 40 Muhamasheen families, the resident told the Sana’a Center.

Another Muhamash in Qataba told the Sana’a Center that the local community resents the distribution of aid to the Muhamasheen. Only 283 Muhamasheen families in Qataba were receiving humanitarian assistance from the World Food Programme in April, he said, emphasizing that the group needs not just food, but also health and education assistance, protection from violence, and most importantly, safe shelter. “We don’t even have a foothold in which to settle; we are threatened with eviction by force by the landowners at any time,” he said.

Taiz Governorate

The situation of Muhamasheen in Taiz, which has been an active frontline in the conflict, differs between districts, a local aid worker who manages food aid distribution in al-Qahirah district told the Sana’a Center. International organizations include Muhamasheen in beneficiary lists in Taiz, however this has created some resentment, he said. Local committee representatives and local organizations complain that the Muhamasheen are the primary recipients of international humanitarian assistance; “I don’t know if this is really the case or if this comes from a racist perspective,” the aid worker said. As in other parts of Yemen, aid distribution is irregular and unpredictable in Taiz, a resident of al-Azaez district said. Around 300 Muhamasheen households in the district were receiving monthly assistance from different organizations, but in May 2019, 200 of these households received nothing because the aid organization’s project had concluded.

Sawan district, Sana’a City

In Yemen’s capital Sana’a, Muhamasheen in Sawan district told the Sana’a Center that some people from the community have retained their jobs as street cleaners, but that conditions have become more difficult during the war. They generally do not have proper equipment for the job, collecting rubbish by hand and without gloves, exposing themselves to health risks. “Our health and personal hygiene is affected by doing this,” a street cleaner from the Muhamasheen said. His salary is 25,000 Yemeni rials per month (around US$45)[19]; the conflict-driven collapse of the Yemeni currency’s value and the inflation in food prices means that this is not enough to pay even one week’s expenses, he added.

Aden Governorate

Many Muhamasheen in Aden live in Dar Saad, an area with poor services, frequent power cuts and scarce water. Of those who are employed, most are street cleaners, although some women are domestic workers while men have earned money in work as varied as collecting scrap plastic to fighting for one of the various local militias. Some Muhamasheen in Aden also receive cash assistance or food baskets from the World Food Programme. A local activist told the Sana’a Center that Dar Saad has only a single road that was not fully paved; she noted that this was unusual for Aden, where most roads are paved even in poor areas like Basatin, which is mostly populated by Somali refugees.

Discrimination against Muhamasheen is generally less intense in Aden than in parts of northern Yemen, but it is still prevalent. The local activist has worked to create child-friendly spaces in Aden and has involved Muhamasheen children in these activities. However, she said this has caused problems with parents who refuse to let their children play with Muhamasheen children; it is a challenge to convince these parents to let their children treat their peers equally, she explained.

Marib City, Marib Governorate

The relatively high level of security in Marib has brought hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people to the city since the conflict began. In 2017, the governorate struck a deal with the internationally recognized government to keep up to 20 percent of revenues from locally-extracted resources. This has contributed to economic growth, which has also attracted IDPs.

Muhamasheen have been among the IDPs who have settled in Marib, and locals told the Sana’a Center they have observed an increasing number of Muhamasheen women begging in the city. Muhamasheen in Marib predominantly work in garbage collection and agriculture, and live in concentrated communities in several districts of the city. Internally displaced Muhamasheen reported receiving some humanitarian assistance, while civil society and humanitarian organizations provide aid targeted broadly toward those in need, which some Muhamasheen benefit from.

The rapid demographic and economic growth in Marib has led to the physical expansion of the city; for some Muhamasheen, this has meant that their dwellings which were previously on the outskirts of the city are now in the city center. This has improved their access to services, including electricity. Muhamasheen have resisted attempts by local authorities to move them from these areas. Local authorities have paved Al-Arbaeen Road in Marib City, but were forced to stop at the Muhamasheen settlement in the area, as the residents refused to leave.

Looking Ahead: Recommendations to Address Systemic Marginalization

The following are recommendations to improve the integration and inclusion of Muhamasheen in Yemen:

-

Yemeni authorities should adopt the outcomes of the National Dialogue Conference focused on the inclusion and integration of Muhamasheen communities.

- Among the most important of these is the establishment of a quota for the participation of Muhamasheen in all government authorities and bodies. Representation at decision-making levels could be a transformative first step toward equality and the achievement of legal, economic, social, civil and political rights for the Muhamasheen.

- The enactment of laws criminalizing discrimination on the grounds of descent or race should also be a priority.

- Any post-conflict government should implement a comprehensive national strategy to improve access to education, health, housing and public services for Muhamasheen communities, and should provide opportunities for technical and vocational training to improve their employment prospects.

- The government should include Muhamasheen as recipients of the Social Welfare Fund; this would contribute to alleviating the extreme poverty in the community.

- Donor states and institutions and humanitarian organizations should insist on the inclusion of Muhamasheen in programs they support or implement in Yemen. They should also take steps to ensure that humanitarian assistance and development programs reach Muhamasheen communities, for example through cooperation with civil society organizations representing the Muhamasheen.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Endnotes

- “Report of the Special Rapporteur on Minority Issues,” United Nations Human Rights Council Thirty-First Session, January 28, 2016. Available at http://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/31/56. Accessed June 4, 2019

- Robert F. Worth, “Languishing at the Bottom of Yemen’s Ladder,” New York Times, February 27, 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/27/world/middleeast/27yemen.html?partner=rssnyt&emc=rss&module=ArrowsNav&contentCollection=Middle%20East&action=keypress®ion=FixedLeft&pgtype=article. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- Ibid.

- “From Night to Darker Night: Addressing Discrimination and Inequality in Yemen.” Equal Rights Trust, June 2018, https://www.equalrightstrust.org/ertdocumentbank/Yemen_EN_online%20version.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- “UNICEF Situation Report – Muhammasheen mapping update,” UNICEF, January 2015, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNICEF%20Yemen%20SitRep%20January%202015.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- “From Night to Darker Night: Addressing Discrimination and Inequality in Yemen.” Equal Rights Trust, June 2018, https://www.equalrightstrust.org/ertdocumentbank/Yemen_EN_online%20version.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- “UNICEF Situation Report – Muhammasheen mapping update,” UNICEF, January 2015, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNICEF%20Yemen%20SitRep%20January%202015.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- Rania El Rajji, “’Even war discriminates’: Yemen’s minorities, exiled at home,” Minority Rights Group International, January 2016, https://minorityrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/MRG_Brief_Yemen_Jan16.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- Tom Finn, “In revolt, Yemeni “untouchables” hope for path out of misery,” March 7, 2012, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-yemen-akhdam/in-revolt-yemeni-untouchables-hope-for-path-out-of-misery-idUSLNE82602Q20120307. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- “Outcomes Document,” National Dialogue Conference, assembled by the Political Settlements Research Programme (University of Edinburgh) from non-official translations of Working Group Outcomes.

- “Annual report of the UNHCHR and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General,” UN Human Rights Council 27th session, August 27, 2014, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/Yemen%20A%20HRC%2027%2044.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- “The 2015 Draft Yemeni Constitution,” January 15, 2015, Constitution Net, http://constitutionnet.org/sites/default/files/2017-07/2015%20-%20Draft%20constitution%20%28English%29.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- “2019 Humanitarian Needs Overview – Yemen,” UN OCHA, December 2018, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2019_Yemen_HNO_FINAL.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- Rania El Rajji, “’Even war discriminates’: Yemen’s minorities, exiled at home,” Minority Rights Group International, January 2016, https://minorityrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/MRG_Brief_Yemen_Jan16.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- “From Night to Darker Night: Addressing Discrimination and Inequality in Yemen.” Equal Rights Trust, June 2018, https://www.equalrightstrust.org/ertdocumentbank/Yemen_EN_online%20version.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- Ibid

- Based on the exchange rate in Sana’a on May 20, 2019

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية