A view of Al Saleh Mosque in Sana’a, inaugurated in November 2008 and named after former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, which Houthi authorities have taken to calling “The People’s Mosque,” on April 26, 2019 // Photo Credit: Asem Alposi

The Sana’a Center Editorial

The Sana’a Center Editorial

Yemen’s Game of Parliaments

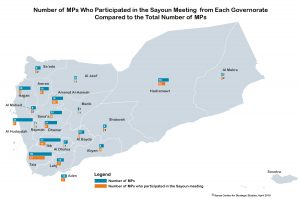

April saw the most powerful monarchy in the world – one with few democratic inclinations of its own – send armed forces and air defenses into its southern neighbor to surround a session of parliament and ensure it proceeded. The session was held in neither Yemen’s capital, nor the government’s interim capital; the members of parliament (MPs) were elected 16 years earlier – so long ago that 39 of them had since passed away; and, despite members being promised 500,000 Saudi riyals each just to attend, the session did not make quorum. But such was the case for legitimacy last month in Sayoun, Hadramawt governorate, where President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi convened the Yemeni government for the first time in four years – before traveling back to his home-in-exile in Riyadh.

Simultaneously, 600 kilometers away in Sana’a, the armed Houthi movement – which deposed Hadi in a 2015 coup with the help of the former president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, whom they later murdered – was racing to assert its own legitimacy, staging bi-elections to replace 24 of the deceased MPs. The Houthi leadership, since taking control of the capital, has also regularly staged parliamentary meetings lacking quorum. The reality is that while neither of Yemen’s warring sides can rightly claim the constitutional authority to carry out the functions of parliament, their attempts to do so magnify the rupture of parliament as a national institution.

For Hadi, the Sayoun session was a double-edged sword. While it ostensibly demonstrated that he was at the head of a government, reconvening MPs also demonstrated that there is a government beneath him – one which would constitutionally have the right to replace him should the president die or be otherwise unable to fulfill his duties. Put differently: the only real leverage Hadi had over his Saudi patrons was that they needed him, even if only as a figurehead, to legitimize their intervention in Yemen; now, Riyadh has a plausible Plan ‘B’.

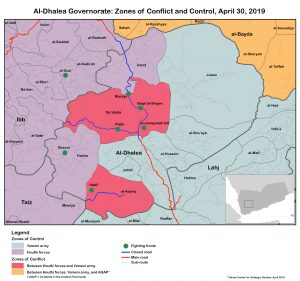

All of this also took place within the context of the Houthi forces’ most significant battlefield gains since the Saudi-led coalition began its intervention in the Yemen conflict in 2015. Advances in al-Dhalea and nearby governorates showed that, after four years on the defensive, Houthi forces still have fight left in them. With December’s United Nations-brokered Stockholm Agreement and the ceasefire around Hudaydah port which it precipitated, the Houthi forces’ greatest battlefield vulnerability was neutralized, and they were free to refocus their efforts elsewhere. The Houthi forces’ gains in April are also forcing the Saudi-led coalition and the Yemeni government to recalibrate and redeploy. This underlines two other apparent issues: (1) it is highly unlikely the Hudaydah ceasefire will translate into a wider peace agreement, and (2) if it was not already painfully obvious after more than four years of attrition, this war is unwinnable.

In considering that, one must weigh that the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) has estimated that the conflict will claim the lives of nearly a quarter of a million people in Yemen – due to either hunger or violence – if it continues through 2019. The country has already been pushed back decades in terms of development, and will continue its regression as long as the conflict continues. This begs the question: when this game of parliaments ends, what will be left to govern?

Contents

Developments in Yemen

International Developments

Endnotes

Developments in Yemen

Political Developments

Hadi Government Holds Parliamentary Session Despite Falling Short of Quorum

April saw an escalation on the latest battleground between President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi’s government, the armed Houthi movement and southern separatists: Yemen’s legislative institutions. On April 13, the internationally recognized government opened its first parliamentary session since the beginning of the conflict — the same day that by-elections were held in Houthi areas for vacant parliamentary seats.[1] The meeting also came only two months after the separatist Southern Transitional Council’s (STC) would-be parliament, the Southern National Assembly, held their second session in Mukalla, Hadramawt governorate.[2]

Formal outcomes of the April 13-16 parliamentary session, staged in Sayoun, Hadramawt, were limited to the ratification of the new state budget and the election of a new speaker — Sultan al-Barakani, a veteran figure in the General People’s Congress (GPC) party and former party whip during former President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s rule. MPs also thanked the Saudi-led coalition for its intervention in the Yemen conflict. At the meeting’s conclusion, Barakani adjourned parliament until after Ramadan, which this year runs from early May to early June.

The 301-seat House of Representatives was elected in 2003, with its term extended in 2009 through a deal between former President Saleh and opposition parties, and then again in 2011 by the Gulf Initiative that aimed to resolve Yemen’s political crisis following the Arab Spring uprisings. Thus, the Parliament has not seen a general election in 16 years. In that time 39 seats have been vacated due to the deaths of MPs, with 11 of these seats filled by local by-elections in 2008. This left 273 living MPs who could potentially have attended the April session in Sayoun. According to the Yemeni constitution, parliamentary quorum requires the attendance of at least half of the members plus one – a mark which the Sayoun session failed to meet, with only 118 MPs present. The STC said that the parliamentary session was unconstitutional and those STC members who are also member of the House of Representatives did not attend.

Regardless of the event’s questionable legality, staging it offered the Hadi government an opportunity to assert its continued international recognition and the continuity of parliament as an institution. However, pervasive insecurity in Aden – and southern separatists’ de facto authority there – undermined prospects to convene parliament in Aden – the Yemeni government’s interim capital. Sana’a Center sources also reported that the United Arab Emirates – a member of the regional military coalition intervening in Yemen on behalf of the government, but also a primary backer of the STC – refused to allow the parliament to meet in Aden or Mukalla, its main zones of influence in Yemen. Saudi Arabia, which heads the regional military coalition, provided a heavy security presence for the event. In the evening prior to the opening session Saudi air defenses positioned around Sayoun shot down almost a dozen aerial drones, according to Sana’a Center sources.

On April 30, members of the Yemeni parliament then met with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in Riyadh. At the meeting, the parliamentarians gave bin Salman a letter formally requesting that Riyadh ease the increasing restrictions, fees and deportations it has been imposing on Yemeni workers in the kingdom. More than a million Yemeni expatriates work in Saudi Arabia, collectively sending home billions of dollars annually; however, Saudi policies to nationalize its labor market have in recent years forced tens of thousands of Yemenis to return home.[3]

Houthis Stage By-Elections

The Houthi authorities – who have regularly held parliamentary sessions in Sana’a with fewer than the legal minimum required attendees – sought to assert their own legitimacy in April by filling the seats of deceased lawmakers. On April 15, the Houthi-controlled Supreme Commission for Elections and Referendum (SCER) said that 24 of the vacant seats in Houthi-controlled areas had been filled, and the new lawmakers were sworn in on April 17. The four remaining vacant parliamentary seats are in territories controlled by anti-Houthi forces. Both the Hadi government and the Houthi leadership denounced the parliamentary moves of the other as illegal.

Military and Security Developments

Houthis Forces Make Largest Territorial Advances Since 2015

While the UN-brokered ceasefire generally held in Hudaydah City, frontlines in other areas saw increased hostilities in April. Al-Dhalea governorate – situated in Yemen’s southwest – saw some of the most intense fighting, as well as neighboring governorates of Abyan, Lahj and al-Bayda. Major escalations took place in al-Dhalea’s northern and western areas bordering the governorates of Ibb and Taiz, respectively, where Houthi forces made gains in Qa’ataba and Hasha districts. Houthi forces also claimed to have taken control of Dhi Na’im district in neighboring al-Bayda governorate. Given their strategic location between Sana’a and Aden, al-Dhalea and al-Bayda act as a gateway between Yemen’s northern and southern governorates. Houthi forces made headway into areas historically seen as part of southern Yemen, giving additional symbolic value to these territorial gains.

In al-Dhalea, fighting has been centered on the mountainous areas of al-Oud — strategically located along the border between al-Dhalea and Ibb and only sparsely populated by remote villages with minimal road access.[4] Yemeni media outlets reported that the Houthi advance was bolstered by support from local tribal leaders and high-level defections within anti-Houthi forces.[5] Houthi forces were largely pushed out of al-Dhalea in 2015, though they maintained a foothold in parts of the northern Damt and Qa’ataba districts.

Toward the end of the month, fighting picked up in al-Dhalea’s western Hasha district. After making rapid advances in the preceding days, on April 24 Houthi forces reportedly took control of the Dhawran area in the center of Hasha.[6] In the last days of April, Houthi forces were in the process of pushing eastwards from Hasha into al-Azariq district.

Houthi forces also made advances in neighboring al-Bayda governorate, taking control of Dhi Na’im district on April 20.[7] Al-Bayda’s local police chief, Brigadier General Ahmed Ali Mohammed al-Humiqani, resigned shortly after, citing the “neglect” of the governorate by the Hadi government and the Saudi-led military coalition in the face of Houthi advances.[8] By the end of the month the increased violence had severed most road networks between northern and southern areas, posing severe risks for both humanitarian operations and the commercial distribution of goods (see ‘Fighting Severs North-South Access Roads, Threatens Aid Operations’ and ‘Severe Shortage of Basic Commodities Imminent’).

Coalition Deploys Reinforcements, Tariq Saleh Given Expanded Role

The Yemeni armed forces and pro-government media reported that coalition airstrikes targeted Houthi positions in northern al-Dhalea, as well as Houthi reinforcements in Ibb and Dhamar, which were reported to be on their way to the frontlines.[9] Anti-Houthi reinforcements also arrived from other governorates; on April 7, the Aden al-Ghad news outlet quoted military sources as saying that forces affiliated with Tariq Saleh’s Republican Guard deployed to the Murays area of Qa’ataba, from their base in Mokha, Taiz.[10]

According to Sana’a Center sources, for several weeks in April, Saleh was in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, where he met with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Deputy Defense Minister Khalid bin Salman, and Prince Fahd bin Turki, commander of the coalition joint forces. The same sources said that coalition leaders have become frustrated with anti-Houthi forces’ lack of progress and aim to transfer greater military responsibilities to Saleh, including the responsibility for the entire western Tihama coast.

Anti-Houthi Forces in Hajjah Push South

In Hajjah governorate on Yemen’s northwestern coast, anti-Houthi forces continued their offensive in Abs district, where ground forces are pushing south in the direction of Hudaydah governorate. Fighting in early April was concentrated in the Bani Hassan area, where UN humanitarian chief Mark Lowcock said 100,000 people were displaced due to the violence.[11]Further north in Hajjah, there was fighting around Nar mountain, close to the Saudi border, and in the Ahem Triangle area. These locations lie northeast and south of the Houthi-controlled Haradh city, respectively, which anti-Houthi forces are attempting to encircle.

Saudi Air Force Bombs Checkpoint in al-Mahra

On April 18, Saudi Apache attack helicopters bombed Labib checkpoint, on the western border of al-Mahra governorate in eastern Yemen. The region, which borders Oman, has to date been isolated from the conflict against Houthi forces that is raging in the country’s western areas. There have, however, been recurring tensions in al-Mahra regarding a growing Saudi military presence in the governorate, which many locals view as an attempt by Riyadh to secure the area for the building of an oil pipeline and to gain greater influence in the region, which borders both Oman and the Gulf of Aden.[12]

Local media reported that the airstrikes on the checkpoint came after the convoy of Governor Rajih Bakrit, who is Saudi-allied, was engaged in a firefight with local tribesmen manning the position.[13] This was the first time the Saudi Air Force has been employed in Riyadh’s dispute with locals in al-Mahra, and as such represents a significant escalation of the situation. Days later, reports emerged that Riyadh was pressuring the Yemeni government to issue an official decree to replace local forces at Labib checkpoint with a Saudi-allied militia, spurring local tribesmen to send reinforcements to buttress the checkpoint.[14]

Economic Developments

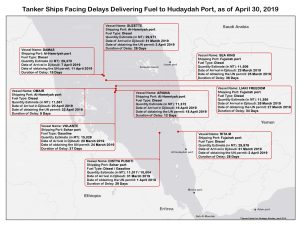

Warring Parties’ Economic Conflict Spurs Fuel Shortages in Northern Yemen

In April, Houthi-controlled areas experienced widespread fuel shortages. The average black market fuel price more than doubled, with 20 liters of gasoline increasing from YR 7,400 to YR 16,000 between April 1 and April 25. The fuel crisis resulted from a drop in deliveries to the Red Sea port of Hudaydah, which began in March though existing stocks delayed the market impact until April. At various points in April there were a dozen or more tanker vessels moored offshore waiting to offload fuel, with Houthi authorities and the Government of Yemen’s Economic Committee trading blame as to why the ships remained idle.

At the heart of the issue was the ongoing struggle between the warring parties over the regulation of imports and control of the country’s currency stocks. Since the Yemeni government’s Decree 75 came into effect in October 2018, the Economic Committee has increasingly sought to regulate fuel imports, with fuel importers’ previously unregulated demand for foreign currency being seen by many as the primary cause of the domestic currency’s past instability.[15]

Under Decree 75, all fuel importers must apply to the Economic Committee to qualify to import fuel, with the committee’s decisions in this regard enforced by the Saudi-led coalition’s naval forces. Among the requirements is that traders must provide three years of bank statements to qualify to import fuel – a clause that has disqualified many Houthi-aligned traders who are new to the market. Importers must also document how they intend to finance the delivery and pay the exporter. Houthi authorities retaliated by threatening the country’s major bankers and traders – most of whom are based in Sana’a – not to work with the Economic Committee.

Until the end of March 2019, the central bank in Aden was offering foreign currency funds to only a limited number of fuel importers, though all traders were free to import fuel if they met the Economic Committee’s requirements. On April 2, the CBY in Aden adopted a unified mechanism for importing fuel. Under this mechanism, all fuel importers must purchase foreign currency from the central bank in Aden – via deposits at select commercial banks which would then be transferred to the Aden central bank – in order to obtain the importation license. While this would help ease downward pressure on the Yemeni rial in the local currency market, it would also draw large amounts of cash out of Houthi-controlled areas and magnify the cash liquidity crisis there.

Anticipating this move, in March the Houthi authorities began pressuring importers in areas under their control to place orders for fuel without applying to the Economic Committee for a license. The result was that in April numerous tankers carrying fuel arrived in the Red Sea, passed the through the United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism (UNVIM) in Djibouti – which inspects all ships entering Hudaydah port – but were then denied permission from the Saudi-led coalition to dock and offload.

On April 15, the Economic Committee posted a chart online listing 12 vessels carrying an estimated total of 68,600 tons of petrol and 153,000 tons of diesel destined for Yemen.[16] According to the chart, at that time only one ship, belonging to the World Food Programme, had been granted approval to dock and offload fuel by the Economic Committee. The Economic Committee said that eight additional vessels would be granted approval if the importers submitted their applications.[17] The fuel crisis in northern Yemen only began to recede on April 25, with the importers having submitted their applications, which the Economic Committee approved, and the tankers were allowed to dock, with the Houthi authorities’ acquiescence. As of April 30, however, at least nine tanker ships remained idle in the Red Sea; these were divided between vessels for which the importer had not submitted an application to the Economic Committee, and those that had and were approved but the Houthi authorities were barring from offloading.

Fuel Crisis Becomes Political Football Between Warring Parties

Over the course of April, the coverage of different pro-government and pro-Houthi sources on Facebook, Twitter and other online platforms highlighted how the fuel crisis was heavily politicized. There was a feverous exchange of visuals and infographics that were designed to cast blame for the crisis on their political opponents.

The Yemeni government claimed the Houthis were responsible for the crisis through pressuring fuel importers to stop submitting fuel import applications to the Economic Committee, and encouraging certain fuel importers to send fuel shipments to Yemen despite the fact that they were unlikely to obtain authorization from the Economic Committee. The Houthis meanwhile framed the crisis as being a symptom of the Yemeni government’s actions, and specifically the implementation of Decree 75.

Severe Shortage of Basic Commodities Imminent

On April 15, UN humanitarian chief Mark Lowcock warned that commercial food imports into Yemen through Hudaydah and Saleef ports were down 40 percent during the first three months of 2019 compared to the last quarter of 2018, in a briefing to the Security Council.[18]

Prominent Yemeni food importers told the Sana’a Center in April that a severe shortage of basic commodities was likely to begin in June. Many importers have ceased new orders because of the central bank in Aden’s requirement that importers must purchase letters of credit using Yemeni rial banknotes, and Houthi authorities’ ban on commercial banks transferring cash liquidity from Sana’a to Aden. The importers said that once current commodities stocks are exhausted, shortages will ensue.

The importers also said that the closure of most roads between Sana’a and Aden due to an escalation in fighting (see ‘Houthis Forces Make Largest Territorial Advances Since 2015’) would severely disrupt commercial deliveries and operations. Most of Yemen’s manufacturing capacity is located in Houthi-controlled areas, while currently only Aden port can receive containerized cargo (Hudaydah and nearby ports can currently only receive bulk cargo). A prolonged closure of the roads would lead to a shortage of imports for many factories in the north, while finished products would be unable to reach the south.

Aid Recipients Still Losing Out to Currency Arbitrage

On March 10, UNICEF announced that it would pay US$50 monthly, in local currency, to 136,000 teachers and school staff to help keep classes for children running. The Sana’a Center has since learned that the UN exchanged its foreign currency at a rate of YR 480 per US$1, at a time when the market exchange rate was YR 580 per US$1, meaning the Yemeni banks performing the exchange — Alkuraimi Bank for Islamic Microfinance and Al Amal Microfinance Bank — profited YR 100 per US$1 exchanged. As the Sana’a Center has previously reported, Yemeni banks have regularly profited from currency arbitrage when handling funds from international organizations entering the country, at the expense of aid recipients.[19]

Houthi Authorities Attempt an Electronic Rial Payment System, Again

The Houthi authorities have been suffering from a liquidity shortage in local currency banknotes since the Yemeni government fragmented the central bank management between Sana’a and Aden in September 2016.[20] Two currency-related factors have contributed to the intensifying liquidity crisis in Houthi-controlled areas: the Houthi authorities’ consistent refusal to allow the circulation of new banknotes printed by the central bank in Aden, and their inability to replenish physical currency banknotes – meaning bills printed prior to September 2016, many of which are damaged and would otherwise be replaced, are still in circulation.

In an attempt to address the liquidity crisis and ensure partial salary payments to public servants working in areas under its control, the Houthi authorities’ so-called ‘National Salvation Government’ in Sana’a began implementing an electronic rial system at the end of April. The Houthi-run Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) was selected for the initial trial of this system after other public institutions – including the Yemeni Telecommunications Corporation – outright refused to receive salary payments via the electronic system. The YPC employees’ syndicate organized large demonstrations against adopting the new payment system, leading Houthi authorities to imprison three syndicate members. (As of writing, it is not clear whether the system would be implemented.)

In March 2018, the Houthi authorities launched a pilot program for an electronic rial system.[21] The Sana’a Center Economic Unit’s analysis is that attempts to electronically replace domestic currency banknotes will create pressure on the local currency through increased demand for imported commodities. This will quickly lead to a price disparity in the market where vendors will charge one price in exchange for physical banknotes and another for electronic rials. A similar price disparity was observed when Houthi authorities attempted a voucher payment system in April 2017.[22]

Central Bank in Aden Offers Commercial Banks Preferential Exchange Rate

On April 22, the central bank in Aden announced that it would – in exchange for physical domestic banknotes – sell Yemeni commercial and Islamic banks foreign currency at a rate of YR506 per US$1, or the current market rate if the rate was lower than YR506-US$1.[23] As part of this new incentive, the central bank in Aden is also offering to facilitate foreign currency deposits to the accounts that Yemeni banks hold with correspondent banks abroad, to help underwrite the letters of credit and financial transfers for fuel, food and medicine imports.

As with other efforts the Aden central bank and Economic Committee are making to supply the market with foreign currency, while this move will help ease downward pressure on the Yemeni rial it will also draw physical currency out of Houthi-controlled areas and magnify the liquidity crisis there.

The government’s new banking policy was likely introduced in response to steps the Houthi authorities took in March to ban Yemeni banks from opening letters of credit with the central bank in Aden for food and medicine importers headquartered in Houthi-controlled areas.[24] These are among the measures the government and the Houthi authorities have recently taken – new, divergent and conflicting regulations – that make it difficult for Yemeni banks to operate.

Other Economic Developments in Brief

- April 6: As part of an annual series of meetings, a Yemeni government delegation traveled to Washington, D.C. for a 10-day trip to meet with officials from the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the US Treasury Department and US State Department.[25] The delegation, which was mainly comprised of senior representatives of the Central Bank in Aden, notably included the banks’s governor Hafedh Mayad and Minister of Planning and International Cooperation Najeeb al-Awj.

- April 12: The central bank in Aden announced that flour would be added to the list of essential commodities for which the bank will issue letters of credit, financed by the US$2 billion deposit Saudi Arabia made in January 2018.[26]

- April 24: The central bank in Aden announced the arrival of the first financial transfer from the Saudi government as part of the agreement reached on March 31.[27] The agreement stipulates that Riyadh will direct foreign funds it is transferring into Yemen – both payments to local stakeholders and financial assistance for the Yemeni government’s military and civilian budgets – through the Central Bank in Aden. According to a banking source close to the developments, the total amount of the Saudi transfers is an estimated $120 million per month.[28]

- April 27: Yemen’s Development Champions – a group of prominent Yemeni business people and economic experts – held their fifth forum in Amman, organized by the Sana’a Center and partner organizations.[29] Over three days, the Champions discussed mechanisms to restructure public finances and secure the return of Yemeni capital post-conflict.

- April 28: Houthi leader Abdelmalik al-Houthi met with heads of banks and financial institutions in Yemen to discuss ways to increase state revenues, specifically through Zakat and taxation, according to sources who attended the meeting and spoke to Sana’a Center.[30] Bankers also raised concerns that prospective Houthi plans to confiscate the assets and accounts of political rivals from the banks would be deeply problematic for them, to which al-Houthi responded that he would explore an asset freeze instead.

Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments

UNDP: Conflict Responsible For 233,000 Deaths

The conflict in Yemen will have claimed 233,000 lives by the end of 2019, either by fighting or through lack of access to food, health services and infrastructure, according to a study commissioned by the UN Development Programme (UNDP).[31] Sixty percent of these deaths will be children under five. (An April 23 report from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project stated that fighting alone had killed more than 70,000 people since 2016.[32])

The report examines the impact of the conflict on Yemen’s development. It finds that the war has already reversed Yemen’s development gains by 26 years: if the conflict continues until 2030, it will set back Yemen’s development by nearly four decades. Child mortality has risen from 46.3 deaths per 1,000 births in 2014 to 69.6 in 2019; this figure could reach 136.6 in 2030 if the conflict is not resolved. The percentage of people in extreme poverty has nearly tripled during the conflict, from 18.8 percent in 2014 to 58.3 percent in 2019. The report estimates that if the war continues until 2022, it will cost 482,000 lives; this figure is projected to rise to 1.8 million should the conflict persist until 2030. Meanwhile, Yemen has lost US$89 billion in economic output from the conflict, and the GDP per capita (at purchasing power parity) has sunk by US$2,000 during the war. If the conflict continues, lost economic output will rise to $US181 billion by 2022 and to US$657 billion by 2030, the study forecasts.

The study also offers a projection of a counterfactual scenario in which the conflict did not happen. In 2014, half the population of Yemen lived in poverty and the country was struggling with food insecurity and poor infrastructure; Yemen was unlikely to achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 even in the absence of conflict. But the country was steadily improving. The conflict — which the UNDP describes as a “war on children” — has decimated a generation, reversing development gains for those who survive. The impact of the conflict will last far beyond 2030, the report notes; as well as the damage to infrastructure, many of those who survive the conflict will have suffered stunted growth, which can lead to lower educational achievements and lost wages.

Fighting Severs North-South Access Roads, Threatens Aid Operations

Increased fighting, damage to infrastructure and intensified security concerns have threatened the humanitarian response in al-Dhalea and potentially other governorates further north. On April 22, pro-government media outlets reported that Houthi forces detonated explosives on al-Watif Bridge in al-Dhalea’s Qa’ataba district, which connects Ibb and al-Dhalea.[33] The bridge lies on one of the roads connecting Aden to Sana’a and was the only main north-south route still generally accessible. Alternative routes were often largely impassable. The Sana’a Center was shown video of one instance at al-Khla mountain in Yafa’a district, Lahj governorate, where a line of hundreds of truck had broken down trying to traverse a twisting mountain road.

On April 23, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) said that it had been forced to suspend or relocate its critical programming due to the fighting.[34] This included mobile health clinics and cholera treatment in al-Dhalea governorate. The IRC said the severing of the road between Sana’a and Aden had also complicated the transport and delivery of medical and food supplies around Yemen.

Local Authorities Detain Thousands of Migrants in Aden

Eight migrants have died from preventable illnesses and at least two were shot in makeshift migrant detention camps set up in April in Aden, Lahj and Abyan governorates, the International Organization for Migration said on May 2.[35] They were among around 5,000 irregular migrants, mostly Ethiopians, detained by local authorities in April, the IOM said. Yemeni security officials told the Associated Press on April 24 that police had detained 5,000 migrants who were trying to cross into Saudi Arabia.[36] The IOM said the detainees, including hundreds of children, were being held at al-Mansoura football stadium in Aden City and at a military camp in Lahj.[37]

On April 25, some migrants escaped after local youths opened the gates of al-Mansoura stadium, but they were subsequently recaptured and held at another stadium in Sheikh Osman. The IOM said the stadiums and the military camp were not fit to accommodate large numbers of people; they lack clean water, safe sanitation and risk the spread of disease. The eight migrant deaths were caused by complications from acute watery diarrhoea (AWD), the IOM said; authorities at the military camp in Lahj have detected 200 cases of AWD among 1,400 detainees. On April 30, guards opened fire on migrants at the al-Mansoura football stadium, injuring two people including a teenage boy who may be paralyzed for life as a result.

UNSC Briefing: More than 100,000 Displaced in Hajjah, Cholera in Resurgence

On April 15, the UN Humanitarian Chief Mark Lowcock told the Security Council that despite the ceasefire largely holding in Hudaydah governorate, fighting to the north in Kushar district, Hajjah governorate, had displaced 50,000 people since February.[38] In Abs district, nearly 100,000 people had been displaced in the last two weeks, he said. Lowcock warned of catastrophic consequences if fighting damaged or cut off the main water source in Abs, which serves over 200,000 people, or if the battle moved south toward Hudaydah governorate, which could result in the displacement of up to 400,000 residents.

The under-secretary also noted a resurgence of cholera in the country. Despite efforts to counter the epidemic, nearly 200,000 suspected cases have been reported by humanitarian agencies in 2019, triple the number during the same period in 2018, he said. The first week of April saw the highest number of suspected cholera infections since January 2018, with 31,126 suspected cases in 22 of Yemen’s 23 governorates, according to a report by the European Commission.[39] Amid the breakdown of the country’s health system, more than 3,300 cases of diphtheria have also been reported since 2018, which marks the first outbreak of the infection in Yemen since 1982.

Lowcock said that the UN and partner organizations continued to face several hurdles related to the delivery of aid in the country. The World Food Programme (WFP) continues to face challenges accessing the Red Sea Mills in Hudaydah, which contain enough grain to feed 3.7 million people for a month. The UN had briefly gained access to the mills on February 26 for the first time in six months.[40]

Saudi, UAE Not Fulfilling Funding Pledges to Yemen

On the issue of funding, Lowcock noted that the United Nations Yemen Response Plan had only received $276 million so far this year, 10 percent of what was pledged by donor countries at the High Level Pledging Event for the Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen, held on February 26 in Geneva, Switzerland.[41]

The largest pledges came from Saudi Arabia and the UAE, who each promised $750 million. According to Sana’a Center sources, the British government has been pressuring both Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Emirati Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed to disburse the promised funds. Several Sana’a Center sources said that the countries leading the anti-Houthi military coalition in Yemen appear to be delaying payment until they receive assurances of favorable media coverage and visibility. In October 2018, a leaked UN document showed that Saudi Arabia had forced the UN to accept certain public relations conditions that would positively highlight Saudi Arabia’s role in Yemen in exchange for Saudi and Emirati funding for humanitarian relief efforts.[42] According to the leaked document, Saudi demands included that certain UN agencies publish articles in major Western newspapers highlighting the Saudi financial to relief efforts in Yemen. In addition, Saudi Arabia stipulated that aid agencies operating in Yemen agree to a local visibility plan that would ensure that “donors get deserved recognition and not be overshadowed by the recipient’s agencies’ visibility.”[43]

Other Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments in Brief

- April 4: Médecins Sans Frontières suspended patient admissions to its emergency hospital in Aden.[44] On April 2, armed men threatened guards and medical staff before kidnapping a patient at the facility. The patient was found dead later that day on a street in the al-Mansoura district of Aden.

- April 7: Fourteen children were killed and 16 critically injured, most under the age of nine, in a blast near two schools in Sana’a.[45] Houthi authorities said a Saudi-led military coalition airstrike hit houses and a school in a residential area in the capital. The coalition denied carrying out any strikes in the area.[46]

- April 12: 238,000 people in 45 districts in Yemen are at risk of experiencing Integrated Phase Classification 5 (IPC5) levels of food insecurity, according to the Assessment Capacities Project.[47] Level IPC5 indicates an extreme lack of food and other basic needs leading to starvation, death and destitution.

- April 24: Médecins Sans Frontières reported that many Yemeni mothers and children are dying because they cannot reach medical facilities in time to be saved.[48] The report noted that the conflict has severely reduced the number of operational health facilities, while available facilities are often difficult to reach due to the fighting and shifting frontlines.

- April 27: Seven members of a family, including two women, were killed in a bombing in al-Dhalea governorate, Yemeni officials said.[49]

- April 29: A woman and her four sons were killed by a rocket that hit their home in Jabal Habashi, a district in Taiz governorate. The rocket was fired by Houthi forces, according to Al Masdar.[50]

- April 29: Houthi forces detained 21 people during a raid in Bani Khalid in Dhamar governorate, Al Masdar reported.[51]

International Developments

At the United Nations

UN Special Envoy Briefs Security Council on Withdrawal Plan for Hudaydah

Diplomatic efforts related to Yemen at the United Nations in April continued to focus on implementing the terms of the Stockholm Agreement — the UN-mediated deal agreed to by the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the armed Houthi movement.[52] Since the signing of the agreement in December 2018, little progress on fulfilling the terms of the deal has been witnessed on the ground. Both sides in the conflict continue to cling to their own interpretations of the terms agreed to in Sweden and accuse the other party of violating the agreement. The primary stumbling block to the deal’s implementation concerns the mutual redeployment of forces from frontlines in the port city of Hudaydah. The Stockholm Agreement called for both sides to withdraw troops from the city and the ports of Hudaydah, Saleef and Ras Issa, and for the troops to be replaced with local security forces. However, the composition of the local security forces has been a major issue of contention among the warring parties, which thus far has blocked the implementation of the deal (for more information, see The Yemen Review: February 2019).[53]

In mid-April, the UN said that the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the Houthi movement had agreed to a detailed plan for phase one of the withdrawal of military forces in Hudaydah. UN Special Envoy for Yemen Martin Griffiths, who chaired the December 2018 peace talks in Sweden, announced the agreement on April 15 during a briefing to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC).[54] The agreement was reached after negotiations between the parties and the chair of the Redeployment Coordination Committee (RCC) General Michael Lollesgaard. In an interview with Reuters, Griffiths said the UN did not “have an exact date at the moment for the beginning of this physical redeployment,” adding that it hoped to see the withdrawal begin in “a few weeks.”[55]

If both parties adhere to the terms of the redeployment plan, it will mark the first major voluntary drawdown of forces during the conflict in Yemen. According to a UN official who spoke to the Associated Press, phase one would entail coalition and Houthi forces pulling back several kilometers from the current frontlines.[56] The second phase — intended to demilitarize the city and allow for the return of civilian life — would see the further redeployment of fighters 18 to 30 kilometers from the city, depending on the location. The official noted that opposing forces are currently deployed only 100 meters apart in some areas of Hudaydah City.

Griffiths acknowledged during the Security Council briefing that getting the parties to agree on the phase one redeployment plan for Hudaydah had been a “long and difficult process.”[57] The UN envoy had announced progress in March toward implementing phase one of the proposed withdrawal, which he said would be presented to the parties through the RCC for endorsement. However, mistrust led both sides to trade accusations over delays in agreeing to the withdrawal and warnings that open conflict could resume in the city (for more information, see The Yemen Review: March 2019). General Lollesgaard was also unable to hold a joint meeting of the RCC and had to meet separately with Yemeni government and Houthi representatives to discuss the operational details of the plan.[58]

The Stockholm Agreement called for a second round of negotiations between the warring parties in January, but these were postponed due to the lack of progress in implementing the December deal. Diplomatic sources told the Sana’a Center that, subject to progress in Hudaydah, further negotiations could be held after Ramadan. Berlin is among the locations being discussed to host the talks.

In related news, Germany announced that it would contribute 10 soldiers and police officers to the UN observer mission overseeing the ceasefire in Yemen’s Hudaydah. The United Nations Mission to support the Hudaydah Agreement (UNMHA) was formed in January and calls for 75 observers to monitor the ceasefire in the contested port city. According to Sana’a Center sources, only 13 UN observers had actually been deployed in Hudaydah as of the end of April.

Regarding the other aspects of the Stockholm Agreement, no developments were reported in April on the Statement on Taiz. The agreement also included a prisoner exchange deal, which was initially envisioned to take place in January but stalled amid disagreements between the warring parties over the lists of prisoners to be released. Representatives of the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the armed Houthi movement are expected to meet in Amman, Jordan on May 12 to discuss the prisoner swap.

Recent escalations on Yemen’s frontlines (see ‘Houthi Forces Make Largest Territorial Advances Since 2015’) are an illustration of the strictly defined parameters of December’s Stockholm Agreement. Amid UN-backed talks and the shuffle diplomacy of the UN special envoy, both the Houthis and the Government of Yemen have kept a military solution firmly on the table. MPs gathered for the parliamentary meeting in Sayoun reaffirmed their resolve to take Hudaydah by force should the political track fail to deliver a timely outcome.[59] Meanwhile, the Houthis recently announced new missile capabilities and, in a television interview, leader Abdulmalik al-Houthi said that his forces would target Riyadh, Abu Dhabi and Dubai should the coalition-backed offensive on Hudaydah City resume.[60]

In the United States

Trump Vetoes Legislation To End US Support for Coalition In Yemen

On April 16, President Donald Trump vetoed a bipartisan resolution that would end US assistance to the Saudi-led military coalition in Yemen. “This resolution is an unnecessary, dangerous attempt to weaken my constitutional authorities, endangering the lives of American citizens and brave service members,” Trump said in his veto message.[61] He added that, apart from its operations against Al-Qaeda in the Arab Peninsula (AQAP) and the so-called ‘Islamic State’ group, or Daesh, the US was not engaged in the “hostilities” that the legislation seeks to prohibit. On May 2, Republicans in the Senate blocked a resolution that would have overturned the president’s veto.[62]

The US announced an end to aerial refueling for Saudi-led coalition aircraft in November, but still provides intelligence, advisory and logistical assistance. The nature and scope of US support in the war against the armed Houthi movement has been suspected to extend further than publicly acknowledged by the US government; in May 2018, the New York Times reported that US ground troops stationed on Saudi Arabia’s southern border assisted in locating and destroying Houthi weapons caches.[63] Since the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in October last year at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul there has been growing support in Congress for greater scrutiny of Washington’s role in Yemen, including from some Republican lawmakers.

While the resolution was not expected to become law, the veto sends a message of enduring US support for the Saudi-led coalition. Trump’s veto message positions the war in Yemen within regional power struggles, with frequent mention of Iranian support for the Houthis and what he calls Tehran’s “malign activities” in the country. However, growing weariness with the implication for the US of regular coalition airstrikes against civilian targets — as well as the Trump administration’s apparently boundless carte blanche for Saudi Arabia — has begun to create a gulf between the executive branch and lawmakers on both sides of the aisle. The business-as-usual signal also comes as Trump seeks large troop withdrawals from Syria and Afghanistan that he said were in line with his promise to end costly military interventions abroad. An apparent drawdown in forces abroad may go some way to assuaging critics of America’s “endless wars,” but indications are that covert operations and the type of indirect support seen in Yemen has either continued or expanded during Trump’s tenure.[64]

CENTCOM Confirms 8 Strikes Against AQAP Militants in First Quarter of 2019

On April 1, United States Central Command (CENTCOM) said that it had carried out eight strikes targeting AQAP militants in the first three months of 2019.[65] In January, two strikes hit Marib governorate, while six strikes were conducted in al-Bayda governorate in March.

CENTCOM said that one of the January strikes killed Jamal al-Badawi, one of the alleged plotters of the 2000 USS Cole bombing in Aden. In 2003, a US grand jury indicted al-Badawi for his role in the attack, in which 17 American sailors were killed.[66] While the Pentagon is required to release reports on its counterterrorism strikes for purposes of transparency around civilian casualties, other government agencies do not face the same accountability obligations. In March, the White House overturned an executive order that required all “relevant agencies” to provide information related to counterterrorism strikes “outside areas of active hostilities” — which the vast majority of Yemeni territory is designated to be.[67] This removes oversight of any covert CIA operations in Yemen. In May 2017, President Trump gave the CIA new authority to conduct drone strikes, reversing efforts by President Obama’s administration to limit Langley’s drone program.[68]

Yemeni media outlets reported two strikes in April, one in Mahleh district, west Marib, on April 15, and the other in Shibam city, central Hadramawt, on April 7.[69] The news reports described the bombings as US drone strikes. There has been no confirmation by CENTCOM, although the Pentagon rarely issues press releases so soon after a strike unless it involved a high-profile target. Determining responsibility for airstrikes has become more difficult as the Yemen war has progressed, with coalition member states carrying out a relentless air campaign, Houthi forces demonstrating increasing capabilities in deploying militarized drones, and the United Arab Emirates quietly expanding its own drone operations in Yemen with the support of Chinese UAV technology.[70]

Trump Seeking ‘Terrorist’ Designation for Muslim Brotherhood

On April 30, the White House announced that it was working to designate the Muslim Brotherhood as a “foreign terrorist organization.” While some former US officials have expressed skepticism that such a designation could meet legal standards, if successful the move would have wide-ranging financial, legal and political implications for the group and its affiliates across the region, including the Islah party in Yemen.

US Arms Sales to Saudi, UAE Exceed $68 billion During Yemen War

The US has made deals for at least US$68.2 billion worth of arms and military training with Saudi Arabia and the UAE since 2015, according to data collected by the Security Assistance Monitor, a US think tank, and collated by Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ).[71] The figure includes commercial and government arms deals. A US State Department official told ARIJ that American weapons deals to the Saudi-led coalition since the start of the Yemen conflict totaled around $67.4 billion.

In Europe

Leaked Document Details Use of French-Made Weapons in Yemen Conflict

April saw the release of classified military documents detailing France’s involvement in the war in Yemen. The documents, produced by the French Directorate of Military Intelligence, were obtained by Disclose, a French investigative news organization, and provide insight into the Saudi-led coalition’s widespread use of and dependence on Western military hardware.[72]

The documents reveal details on the use of specific French-made weapons in the conflict. One classified report, entitled “Yemen: security situation,” includes maps outlining the position of French-made weapons inside Yemen and along the Saudi border. This report was delivered to French President Emmanuel Macron, Prime Minister Edouard Philippe and France’s defense and foreign ministers in early October 2018. As of September 25, 2018, 48 French-built CAESAR howitzer cannons were positioned along the Saudi-Yemeni border. The report says the artillery is being used to “backup loyalist troops and Saudi armed forces in their progression into Yemeni territory.” The report noted that 436,700 people in Yemen’s Hajjah and Sa’ada governorates fell within range of the artillery fire. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, France has sold 132 CAESARs to Saudi Arabia since 2010. The leaked military report also states that 129 additional CAESAR howitzers are set to be delivered to Saudi Arabia between now and 2023.

The report revealed that French-made tanks were being employed in the conflict. French intelligence estimated that 70 Leclerc-type tanks were stationed in Yemen, with the Emirati military employing around 40 Leclerc tanks at military camps in Mokha, Taiz governorate, and al-Khawkhah in Hudaydah governorate. While the report stated that the tanks had not been “observed on the front line[s]” during the conflict, this narrative was contradicted by Disclose after examining satellite imagery and video shot on the ground in Yemen. The Leclerc-type tanks were deployed in several major coalition offensives, including on the frontlines in Hudaydah in November 2018 as part of the coalition’s efforts to capture the strategically-important port city. According to the US-based Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, the tanks were responsible for 55 civilian deaths during the fighting in Hudaydah.

French-made equipment is also helping the coalition carry out airstrikes in Yemen. According to the leaked documents, Saudi aircraft have been equipped with Damocles pods, which are made by French defense group Thales and maintained by French engineers. The Damocles pod allows pilots to guide missiles via laser to targets on the ground. The technology is also employed on the Emirati air forces’ French-made Mirage fighter planes, which “operate over Yemen.” According to the documents, the UAE had purchased French-made guided missiles for the Mirage aircraft, including Black Shaheen missiles co-developed by France and the UK, and AASM missiles manufactured by the French defense firm Safran. Other French-made equipment is playing a part in non-combat support operations for the coalition. Cougar combat helicopters have been used to transport Saudi troops. In addition, A330 MRTT tanker aircraft, which are built by the European multinational cooperation Airbus, operate from the Saudi air base in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and play a key role in air-to-air refueling operations for combat aircraft over Yemen. In the report, French military intelligence estimates that the Saudi- and Emirati-led coalition has carried out 24,000 airstrikes in Yemen since the beginning of Operation Decisive Storm in March 2015.

Leaked Documents: Saudi Forces ‘Ineffective’, Dependent on Western Support

Overall, the documents paint a negative picture of Saudi military capabilities and highlight how Western arms sales and military advice have supported the anti-Houthi coalition in prosecuting the war in Yemen. The appendix of the report notes that military equipment from the US, the UK, France, Sweden, Austria, South Korea, Italy, and Brazil are all being employed by the coalition to facilitate combat operations. It also describes the Saudi military as operating “ineffectively” and hints that US military backing for coalition partners may be broader than what has been publicly acknowledged by Washington. According to one of the leaked documents, the Saudi air forces’ Close Air Support operations are being supported by “targeting effectuated by American drones.”[73] This information contrasts with the White House’s contention that the US military is not directly involved in hostilities in Yemen.[74]

The revelations from the documents also appear to contradict previous public pronouncements by the French government, which has long contended that French weapons sold to the coalition were being used solely for defensive purposes. During an interview with a French radio station on April 18, Minister of the Armed Forces Florence Parly said that French weapons were “not being used in any offensive in the war in Yemen” and that no evidence existed linking French arms to civilians deaths in the country.[75] France’s domestic intelligence agency is investigating the leaks, which a judicial source characterized as “a compromise of national defense secrecy,” France 24 reported. Responding to the newly-revealed information on the scale of French weapon sales to the coalition, Human Rights Watch called on France and the UK to follow Germany’s lead and halt arm exports to Saudi Arabia, arguing that it is the only position “in line with EU obligations.”[76]

UK Foreign Secretary Hosts Meeting of ‘Quad’ Ministers on Yemen

On April 26, British Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt hosted a meeting in London on the UN-led peace process for Yemen.[77] The gathering brought together ministers from the so-called ‘Quad’ nations – including Hunt, Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir, Emirati Foreign Minister Abdullah bin Zayid bin Sultan, and Acting US Secretary of State for Near East Affairs David Satterfield – and UN Special Envoy for Yemen Martin Griffiths. In the lead up to the London meeting, the Emirati foreign affairs minister hosted US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in the UAE on April 18, during which both officials agreed that all parties in the Yemen conflict “must make good on the commitments they made in Sweden,” the US State Department spokesperson Morgan Ortagus said.[78] Bin Zayed also met with French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian in Paris on April 24.[79]

According to Sana’a Center sources, the four-party discussions between the US, UK, Saudi and the UAE focused mainly on the future political process in Yemen. While the same group of countries had met in the Polish capital Warsaw in February, the sources described the recent meeting as more forward-looking and encouraging.[80]

Germany Approves Shipment of Weapon Parts to Saudi Arabia and the UAE

Germany’s Federal Security Council approved the shipment of weapon parts to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, German media reported on April 12.[81] The reports followed a March decision by Berlin to extend its halt on arm exports to Saudi Arabia (for more information, see The Yemen Review: March 2019).[82] The ban – which was initially put in place in October 2018 after Saudi agents murdered journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul – was renewed for six months until September 30, 2019. However, the recent extension made an exception for joint EU armament projects after pressure from France and the UK. Accessories for the Cobra artillery tracking radar systems, developed jointly by Germany and France, were also approved for export to the UAE. The decision by the Federal Security Council drew criticism from the German opposition, with The Left deputy parliamentary leader Sevim Dagdelen describing the move as “a violation of current European law.”

Rights Groups Join Legal Challenge to UK Arms Exports to Saudi Arabia

Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Oxfam and Rights Watch UK in April joined a legal appeal that seeks to end Britain’s weapon exports to Saudi Arabia.[83] The case, which was filed by the Campaign Against Arms Trade (CAAT) at the Court of Appeal in London and heard from April 9 to 12, challenged the legality of arms exports to Saudi Arabia. Part of the hearing was closed to the public so the government could provide classified evidence. The challenge before the Court of Appeal seeks to overturn a July 2017 ruling by the High Court in London, which said that it was legal for the British government to continue authorizing arm exports to Saudi Arabia.

During the appeal, CAAT argued that British-made weapons were being employed in violations of international law in the conflict in Yemen.[84] Legal counsel for CAAT also cited the humanitarian impact of the Saudi airstrikes, including damage to civilian infrastructure that has contributed to the outbreak of cholera and a food crisis in the country. In addition, CAAT argued that Saudi Arabia’s “indiscriminate” targeting had failed to take “feasible precautions” to differentiate between civilians and combatants, which has led to disproportionate death or injury to civilians.

Meanwhile, legal counsel for the government contended that Secretary of State for Legal Trade Liam Fox, as representative for the government, was entitled to take into account the reliability of reported Saudi violations of international law and factor them into the overall analysis for the decision on whether British military exports to Riyadh should continue. Since the beginning of the conflict in Yemen in 2015, the UK has licensed 4.7 billion British pounds worth of arms sales to Saudi Arabia, CAAT alleges.

Pope Condemns Arms Sales to Saudi Arabia

On March 31, during an interview with Spanish news program Salvados, Pope Francis criticized nations selling weapons to Saudi Arabia, saying they had “no right to talk about peace.”[85] The pontiff’s statement came in response to a question about the Spanish government’s sale of weapons to Riyadh. Pope Francis commented that Spain was not the only country selling arms to Saudi Arabia, and the actions of those nations were “fomenting war in another country,” in reference to the conflict in Yemen.

Hadi Government Blocks EU Delegation from Visiting Sana’a

At the end of April, a planned European Union parliamentary delegation visit to Sana’a was canceled after the Yemeni government blocked approval for the trip with the Saudi-led coalition, which controls Yemeni airspace, according to Sana’a Center diplomatic sources.

This report was prepared by (in alphabetical order): Ali Abdullah, Waleed Alhariri, Ryan Bailey, Anthony Biswell, Hamza al-Hamadi, Bilqees al-Lahbi, Maged al-Madhaji, Farea al-Muslimi, Spencer Osberg, Hannah Patchett, Ghaidaa al-Rashidy, Sala al-Sakkaf, Victoria K. Sauer, Holly Topham, and Aisha al-Warraq.

The Yemen Review – formerly known as Yemen at the UN – is a monthly publication produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. Launched in June 2016, it aims to identify and assess current diplomatic, economic, political, military, security, humanitarian and human rights developments related to Yemen.

In producing The Yemen Review, Sana’a Center staff throughout Yemen and around the world gather information, conduct research, and hold private meetings with local, regional, and international stakeholders in order to analyze domestic and international developments regarding Yemen.

This monthly series is designed to provide readers with contextualized insight into the country’s most important ongoing issues.

This report was developed with the support of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

Endnotes

- “Yemen leader-in-exile Hadi returns for meeting of divided parliament,” Reuters, April 13, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-election/yemen-leader-in-exile-hadi-returns-for-meeting-of-divided-parliament-idUSKCN1RP0CS. Accessed May 1, 2019.

- “Diplomacy Sinking at Hudaydah Port — The Yemen Review, February 2019,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, March 7, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7162. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “Saudi Arabia’s ‘Deportation Storm’,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, April 9, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7303. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “صور للجبال تنشر لأول مرة | العود .. أسد العرين الذي يحرس الضالع” (“Mountain Photos Published For The First Time: Oud … Lion Areen Guarding Al-Dhale”), Maeen Press, April 7, 2019, https://maeenpress.net/newsyemen/6914/. Accessed May 2, 2019.

- “Paving the way for al-Houthi to the secession border… Al-Masdar online traces the details of the full story of Al-Oud front,” Al Masdar, April 21, 2019. https://almasdaronline.com/articles/166834. Accessed May 2, 2019.

- “Al-Dhale .. Houthi gunmen control first security point in Al-Azariq and captivate one of its members,” Al Masdar, April 26, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/167005. Accessed May 2, 2019.

- “After nearly five years of steadfastness the Houthis control Thi Na’em in Al-Baydha,” Al Masdar, April 21, 2019, https://almasdaronline.info/articles/166811. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Al-Baydda provincial police chief resigns from position to protest the failing of resistance,” Al Masdar, April 21, 2019, https://almasdaronline.info/articles/166812. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Coalition airstrikes target Houthis’ reinforcements in Al-Dhale,” September Net: Yemen National Military Web, April 4, 2019, http://en.26sepnews.net/2019/04/04/coalition-airstrikes-target-houthis-reinforcements-in-al-dhale/. Accessed May 2, 2019; “اخر اخبار اليمن – طيران التحالف يدمر عددًا من الأطقم العسكرية ويستهدف تعـزيزات لمليشيا الحوثي في #إب” (“Aviation Alliance destroys a number of military crews and targets reinforcements of the militia Houthi in Ibb”), 7adramout Net, April 5, 2019, https://www.7adramout.net/adnlng/2320217/اخر-اخبار-اليمن—طيران-التحالف-يدمر-عددًا-من-الأطقم-العسكرية-ويستهدف-تعـزيزات-لمليشيا-الحوثي-في-إب.html. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “قوات تابعة لطارق صالح تصل الضالع لصد هجوم الحوثيين” (“Troops of Tariq Saleh arrive at al-Dhalea to repel the Houthi attack”), Adengd, April 7, 2019. http://adengd.net/news/378257/. Accessed May 2, 2019.

- “Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock Briefing to the Security Council on the humanitarian situation in Yemen – New York, 15 April 2019,” UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), April 15, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/under-secretary-general-humanitarian-affairs-and-emergency-relief-coordinator-mark-17. Accessed May 2, 2019.

- “The UN’s Stockholm Syndrome: The Yemen Review, March 2019,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, April 8, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7269#Tribesmen-Clash-With-Saudi-Troops-in-al-Mahra. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “اباتشي السعودية يستهدف نقطة أمنية في المهرة ولجنة الاعتصام: لن نقف مكتوفي الايدي” (“Saudi Apache targets checkpoint in Mahra. Sit-in committee: we will not stand by”) Al Mawqea Post, April 18, 2019, https://almawqeapost.net/news/39857. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “بضغوط من الرياض.. توجيهات رئاسية بتسليم نقطة أمنية في المهرة للقوات السعودية والقبائل تتداعى” (“Under pressure from Riyadh… Presidential directives to hand over.a checkpoint in Mahra to Saudi forces, tribes object”), April 21, 2019, Al Mawqea Post, https://almawqeapost.net/news/39901. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “The Yemen Review – October 2018,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 10, 2018, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/6620. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- Economic Committee, April 15, 2019, https://bit.ly/2ZGHiRY. Accessed April 29, 2019.

- Ibid.

- “Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock Briefing to the Security Council on the humanitarian situation in Yemen,” Reliefweb, April 15, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/under-secretary-general-humanitarian-affairs-and-emergency-relief-coordinator-mark-17. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “Yemen Economic Bulletin: How currency arbitrage has reduced the funds to address the humanitarian crisis,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, September 6, 2017, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/4740. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- Mansour Rageh, Amal Nasser and Farea Al-Muslimi, “Yemen Without a Functioning Central Bank: The Loss of Basic Economic Stabilization and Accelerating Famine,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 2, 2016, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/55. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Yemen at the UN – March 2018 Review,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, April 7, 2018, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/yemen-at-the-un/5563. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Yemen at the UN – April 2017 Review,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, May 8, 2017, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/yemen-at-the-un/99. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- Central Bank of Yemen Aden. 2019. “Announcement for all commercial and Islamic banks” Facebook. April 22, 2019, https://www.facebook.com/AlbnkAlmrkzyAlymnydnCentralBankOfYemenAdenBr/posts/1541450912651819?__tn__=-R. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- Sana’a Center interview on March 22, 2019.

- Central Bank in Aden, April 6, 2019, https://bit.ly/2XTHg7A. Accessed, April 29, 2019.

- Central Bank in Aden, April 12, 2019, https://urlzs.com/Rycd. Accessed April 29, 2019.

- Central Bank in Aden, April 24, 2019, https://bit.ly/2GJNRKR. Accessed April 29, 2019.

- Sana’a Center interview on April 4, 2019.

- “Development Champions Forum Concludes Fifth Meeting,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, May 1, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/news/7348. Accessed May 6, 2019.

- “خاص- زعيم مليشيا الحوثي يلتقي مديري البنوك في صنعاء” (“Special – Houthi militia leader meets bankers in Sana’a”), Khabar News Agency, April 28, 2019, https://www.khabaragency.net/news110311.html. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Assessing the impact of war on Development in Yemen,” United Nations Development Programme, April 23, 2019, https://www.undp.org/content/dam/yemen/General/Docs/ImpactOfWarOnDevelopmentInYemen.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Yemen war death toll surpasses 70,000,” Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, April 23, 2019, https://www.acleddata.com/2019/04/18/press-release-yemen-war-death-toll-surpasses-70000/. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “The militia bursts the “al-Watif” bridge between Ibb and al-Dhale and cuts the highway,” (“المليشيا تفجر جسر “الوطيف” الواصل بين إب والضالع وتقطع الطريق العام”), Al Sahwah Net, April 22, 2019. https://alsahwa-yemen.net/p-29342. Accessed May 2, 2019.

- “Yemen: Uptick in fighting forces IRC to suspend critical life-saving programming,” International Rescue Committee, April 23, 2019, https://www.rescue.org/press-release/yemen-uptick-fighting-forces-irc-suspend-critical-life-saving-programming. Accessed May 2, 2019.

- “Migrants die while detained in inhumane conditions in Yemen,” International Organization of Migration, May 2, 2019, https://www.iom.int/news/migrants-die-while-detained-inhumane-conditions-yemen. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “Yemeni officials say 5,000 migrants detained in Aden,” The Associated Press, April 24, 2019, https://www.apnews.com/a288c477980e4c1a8a14dd17eb67288e. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “Deep Concern as Thousands of Migrants Rounded Up in Yemen,” Reliefweb, April 26, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/deep-concern-thousands-migrants-rounded-yemen. Accessed April 27, 2019.

- “Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock Briefing to the Security Council on the humanitarian situation in Yemen,” UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, April 15, 2019, https://m.reliefweb.int/report/3084613. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “ECHO Daily Flash,” European Commission, April 25, 2019, https://erccportal.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ECHO-Flash/ECHO-Flash-List/yy/2019/mm/4. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “Diplomacy Sinking at Hudaydah Port — The Yemen Review, February 2019,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, March 7, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7162. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “Yemen: Donors pledge US$2.62 billion to support a massive humanitarian operation,” UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, February 26, 2019, https://www.unocha.org/story/yemen-donors-pledge-us26-billion-support-massive-humanitarian-operation. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- Patrick Wintour, “Saudis demanded good publicity over Yemen aid, leaked UN document shows,” The Guardian, October 30, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/oct/30/saudis-demanded-good-publicity-over-yemen-aid-leaked-un-document-shows. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- Ibid.

- “MSF suspends hospital admissions in Aden after patient is kidnapped and killed”, Médecins Sans Frontières, April 04,2019, https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/what-we-do/news-stories/news/yemen-msf-suspends-hospital-admissions-aden-after-patient-kidnapped. Accessed April 27,2019.

- “The United Nations children’s fund says a blast near two schools in Yemen’s rebel-held capital Sana’a killed 14 children and critically injured 16,” SBS News, April 9, 2019, https://www.sbs.com.au/news/un-condemns-deadly-yemen-school-blast. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “Yemenis recount horror of mysterious blast in capital,” The Associated Press, April 8, 2019, https://www.apnews.com/18074f37e82d4546b9bc4768f3c59829. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “Yemen drivers of food insecurity,” ACAPS, April 12, 2019, https://www.acaps.org/sites/acaps/files/products/files/20190411_acaps_yemen_analysis_hub_drivers_of_food_insecurity_in_ipc_5_districts_in_yemen.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2019.

- “Complicated delivery: The Yemeni mothers and children dying without medical care”, Médecins Sans Frontières, April 9, 2019, https://www.msf.org/complicated-delivery-yemeni-mothers-and-children-dying-without-medical-care. Accessed April 28, 2019.

- “Yemen officials say bombing kills 7 family members,” The Associated Press, April 27, 2019, https://www.apnews.com/53fa92b22d504376a07266f584b522c2. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “مقتل أم وأربعة من أبنائها جراء سقوط صاروخ للحوثيين على منزل غرب تعز” (“A mother and her four sons were killed when a Houthi rocket hit a house west of Taiz”), Al Masdar, April 29, 2019, https://www.almasdaronline.com/articles/167078. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “مليشيات الحوثي تداهم قرية في آنس بذمار وتعتقل 21 مواطناً” (“Houthi militias raided a village in Anas Bhammar and detained 21 citizens”) Al Masdar, April 29, 2019, https://https://www.almasdaronline.com/articles/167128. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “Full Text of the Stockholm Agreement,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary General for Yemen,” December 13, 2018, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/full-text-stockholm-agreement. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “The Yemen Review: February 2019”, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, March 7, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7162. Accessed May 6, 2019.

- “Starvation, Diplomacy and Ruthless Friends: The Yemen Review 2018,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, January 22, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/6808. Accessed May 5, 2019; “Briefing of Martin Griffiths, UN Special Envoy for Yemen to the Security Council,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, April 15, 2019, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/briefing-martin-griffiths-un-special-envoy-yemen-security-council. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- Aziz El Yakkoubi, “U.N. envoy sees troop withdrawal in Yemen’s Hodeidah within weeks,” Reuters, April 18, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security/u-n-envoy-sees-troop-withdrawal-in-yemens-hodeidah-within-weeks-idUSKCN1RU265?il=0. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- Edith Lederer, “UN Envoy: Yemen parties agree on initial Hodeidah withdrawals,” The Associated Press, April 15, 2019, https://www.apnews.com/8f254a6838f54166bf7a5ab50f7904a8. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “Briefing of Martin Griffiths, UN Special Envoy for Yemen to the Security Council,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, April 15, 2019, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/briefing-martin-griffiths-un-special-envoy-yemen-security-council. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Yemen Brief and Consultations,” What’s in Blue, April 15, 2019, https://www.whatsinblue.org/2019/04/yemen-briefing-and-consultations-8.php. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “نص البيان الختامي الصادر عن جلسات مجلس النواب في سيئون” (“Text of the final statement issued by the meetings of the House of Representatives in Sayoun”), Rai Al-Yemen, April 17, 2019. https://raialyemen.com/news5495.html. Accessed May 2, 2019.

- “متحدث القوات المسلحة يكشف عن صاروخ باليستي جديد” (“Armed Forces spokesman reveals new ballistic missile”), 26 September News, April 13, 2019, https://www.26sep.net/news_details.php?sid=154009. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Presidential Veto Message to the Senate to Accompany S.J. Res. 7,” April 16, 2019, Presidential Memoranda, US White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/presidential-veto-message-senate-accompany-s-j-res-7/. Accessed April 29, 2019.

- “Senate fails to override Trump’s veto of resolution demanding end to U.S. involvement in Yemen war,” The Washington Post, May 2, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/senate-fails-to-override-trumps-veto-of-resolution-demanding-end-to-us-involvement-in-yemen/2019/05/02/4bd0a524-6cf9-11e9-8f44-e8d8bb1df986_story.html?utm_term=.b419e87decd8. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- Helene Cooper, Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Eric Schmitt, “Army Special Forces Secretly Help Saudis Combat Threat From Yemen Rebels,” The New York Times, May 3, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/03/us/politics/green-berets-saudi-yemen-border-houthi.html. Accessed April 30, 2019.

- Stephen Tankel, “Donald Trump’s Shadow War,” Politico, May 9, 2018, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/05/09/donald-trumps-shadow-war-218327. Accessed April 29, 2019.

- “CENTCOM Yemen Strike Summary Jan. 1 – Apr. 1, 2019,” US Central Command, April 1, 2019. https://www.centcom.mil/MEDIA/PRESS-RELEASES/Press-Release-View/Article/1801674/centcom-yemen-strike-summary-jan-1-apr-1-2019/. Accessed May 1, 2019.

- Gregory Johnsen, “US Military’s Ambiguous Definition of a ‘Legitimate’ Target,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, February 20, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7076. Accessed May 1, 2019.

- “The UN’s Stockholm Syndrome – The Yemen Review, March 2019,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, April 29, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7269#White-House-Revokes-US-Military-Drone-Strike-Reporting-Requirement. Accessed April 29, 2019.

- “Trump gives CIA authority to conduct drone strikes: WSJ,” Reuters, March 14, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-cia-drones-idUSKBN16K2SE. Accessed April 29, 2019.

- “A violent explosion shakes the city of Shibam in Hadramout,” Cratersky, April 7, 2019, https://cratersky.net/posts/13666. Accessed April 30, 2019; “A US plane kills two people in Mahal, Marib,” News Yemen, April 15, 2019, https://newsyemen.net/news40341.html. Accessed April 30, 2019.

- “Stockholm Agreement Meets Yemeni Reality – The Yemen Review, January 2019,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, February 11, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7027#Houthi-UAV-attacks-Coalition-Airstrikes-in-Retaliation. Accessed April 30, 2019; Rawan Shaif and Jack Watling, “How the UAE’s Chinese-Made Drone Is Changing the War in Yemen,” Foreign Policy, April 27, 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/04/27/drone-wars-how-the-uaes-chinese-made-drone-is-changing-the-war-in-yemen/. Accessed April 30, 2019.

- Frank Andrews, “التكلفة الحقيقية لصفقات السلاح الأميركية لحلفائها في حرب اليمن” (“The real cost of US arms deals to its allies in the Yemen war,” Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism”), April 9, 2019, https://arij.net/report/التكلفة-الحقيقية-لصفقات-السلاح-الأمي/. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- “Made In France,” Disclose, April 15, 2019, https://made-in-france.disclose.ngo/en/chapter/yemen-papers. Accessed May 4, 2019.

- Alex Emmons, “Secret Report Reveals Saudi Incompetence and Widespread Use of U.S. Weapons in Yemen,” The Intercept, April 15, 2019, https://theintercept.com/2019/04/15/saudi-weapons-yemen-us-france/. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “US lawmakers vote to end US support for war in Yemen,” The Guardian, February 14, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/feb/13/us-congress-house-yemen-war-trump-saudi-arabia. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “French weapons not used against civilians in Yemen: minister,” Reuters, April 18, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-france-arms/french-weapons-not-used-against-civilians-in-yemen-minister-idUSKCN1RU0H0. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “UK, France Should Join German Saudi Arms Embargo,” Human Rights Watch, April 12, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/04/12/uk-france-should-join-german-saudi-arms-embargo. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Yemen: Foreign Secretary to host meeting with Saudi, Emirati and US counterparts,” Foreign & Commonwealth Office, UK Government, April 26, 2019, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/yemen-foreign-secretary-to-host-meeting-with-saudi-emirati-and-us-counterparts. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Secretary Pompeo’s Meeting With Foreign Minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan of the United Arab Emirates,” US Mission United Arab Emirates, https://ae.usembassy.gov/secretary-pompeos-meeting-with-foreign-minister-sheikh-abdullah-bin-zayed-al-nahyan-of-the-united-arab-emirates/. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Abdullah bin Zayed meets French Foreign Minister,” The National, April 25, 2019, https://www.thenational.ae/uae/abdullah-bin-zayed-meets-french-foreign-minister-1.853356. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Jeremy Hunt to chair Yemen Quad meeting on next steps in peace process,” Foreign & Commonwealth Office, UK Government, February 13, 2019, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/jeremy-hunt-to-chair-yemen-quad-meeting-on-next-steps-in-peace-process. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Germany exporting weapons to Saudi Arabia and UAE — reports,” Deutsche Welle, April 12, 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/germany-exporting-weapons-to-saudi-arabia-and-uae-reports/a-48296155. Accessed May 5, 2019.

- “Bundesregierung verlängert Rüstungsembargo gegen Saudi-Arabien,” (“Federal Government extended arms embargo against Saudi Arabia”) Spiegel Online, March 29, 2019.