The Sana’a Center Editorial

Signing Over Sovereignty

History will likely record the Riyadh Agreement as a game-changing moment in the ongoing Yemeni conflict – how exactly the game will change is still far from certain. What the agreement signed on November 5 in the Saudi capital may mean is that for the first time since the war began the disparate forces that make up the anti-Houthi coalition could come under a unified command and control, and that there may be one fewer state-within-a-state in Yemen to contend with.

History will likely record the Riyadh Agreement as a game-changing moment in the ongoing Yemeni conflict – how exactly the game will change is still far from certain. What the agreement signed on November 5 in the Saudi capital may mean is that for the first time since the war began the disparate forces that make up the anti-Houthi coalition could come under a unified command and control, and that there may be one fewer state-within-a-state in Yemen to contend with.

While Yemen’s internationally recognized government and the secessionist Southern Transitional Council (STC) had been at odds since the latter’s inception in 2017, more recently there has also been searing tension between the two primary backers of these Yemeni parties, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, respectively. The Riyadh Agreement seeks to put these differences to rest: it lays out steps for the STC, both politically and militarily, to be absorbed into the Yemeni government. While the two Yemeni parties are signatories to the agreement, its clauses pave the way for both, and all other military and security forces in southern Yemen, to come under Saudi Arabia’s charge. The agreement would thus have the UAE relinquishing its authority over the multitude of militias it has recruited, trained, armed and financed since it entered the war in 2015 as Saudi Arabia’s main coalition partner in a regional military intervention in Yemen.

In reshaping the Yemeni cabinet and making it explicitly beholden to Saudi Arabia, the Riyadh Agreement could mean that President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi’s decisions will no longer be dictated by his sons or his political ally, Yemen’s Islah Party. Instead, Hadi and the STC have accepted that all major government actions be subordinated to Saudi Arabia. The STC, in an abrupt turn, also has accepted to be under an arrangement that explicitly endorses a unified Yemeni state, in so doing opening the door for its representatives to be present at any future United Nations-led peace talks to end the wider war. By staging a coup against the Yemeni government in Aden this past August, the STC has thus earned its place in the cabinet and international recognition, in another normalization of violence as a means to political ends.

From a purely conflict resolution perspective, having more of the main belligerents represented at the table is good news. Before, even if UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths had secured an agreement between warring parties, the large southern constituencies unrepresented at the talks may not have felt beholden to it and could have undermined the effectiveness of the deal on the ground.

With the anti-Houthi side thus seemingly unifying under Saudi patronage, for better or worse, Riyadh now owns what happens, and what doesn’t happen, in southern Yemen. While unwritten in the actual text, it would appear the new hierarchy the agreement envisions will specifically be headed by Saudi Deputy Defense Minister Khalid bin Salman, who has quietly assumed responsibility for the Yemen file from his brother, Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince and defense minister. This was notable in the meetings Khalid held in the months leading up to the Riyadh Agreement with United Arab Emirates Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, the heads of the Yemeni government and the STC, and the UN special envoy for Yemen, among others.

Indeed, following the attacks on the Saudi Aramco oil facilities in September, it was Khalid who took point position for Riyadh in back-channel talks with the armed Houthi movement for military de-escalation. The 31-year-old prince will undoubtedly be pushing for the agreement’s success to prove himself worthy of authority in the eyes of King Salman and, most importantly, his brother Mohammed who is soon to be king and will be looking for a new crown prince. Khalid bin Salman’s vested interest in the agreement’s success and the back-channel conversations between him and the Houthis which began in September, as reported by the Sana’a Center, could foster the necessary matrix for a broader peace process in Yemen among all sides. It could allow Saudi Arabia to regain one thing it had in 2011, following the Yemeni uprising, and lost again in 2015 with the start of its military intervention in Yemen, which is the ability to be an umbrella over everyone to reach a peace deal in the country.

A worst-case scenario for the Riyadh Agreement, however, is that it turns into a mass wedding but no one is quite sure who is meant to be married to whom, and chaos ensues. The vastness of the profound military and political reforms that the agreement calls for, the vagueness on the specifics regarding how these reforms should be undertaken and the hyperoptimistic time frame within which they should be completed leaves one to wonder if anything but chaos is possible. Even if the Yemeni government and the STC were entering into the agreement in the spirit of cooperation and good faith – which they most certainly are not – its implementation would be fraught, especially with the process headed by a Saudi bureaucracy known for its bloat and sluggishness. Remember, Saudi Arabia began its military adventure in Yemen claiming that the war would be over in a matter of weeks; now, close to five years later, the lack of foresight those words held is painfully apparent.

There have been various missed opportunities that may have been more conducive to a deal like the Riyadh Agreement to unite the anti-Houthi side: such as July 2015 when the coalition and local forces liberated Aden from Houthi control; or when Hadi sacked Aidarous al-Zubaidi as governor of Aden in April 2017 and before the latter had founded the STC; or when STC-affiliated forces first routed the Yemeni government from Aden in January 2018 and Riyadh and Abu Dhabi had stepped in to resolve the tensions. At best, the current Riyadh Agreement should thus be approached with cautious optimism.

For the agreement to succeed Saudi Arabia cannot approach it as an end in itself, but as part of a larger effort to reconstitute the Yemeni government, end the conflict and bring about stability in its southern neighbor. Three steps to demonstrate this seriousness would be to: 1) put real money and resources into helping reform Yemeni government finances and economic practices, rather than just throwing money at the problem when it reaches a crisis point; 2) reopen Sana’a Airport to commercial flights, beginning with medical evacuations for those with emergencies; 3) stop deporting hundreds of thousands of Yemeni laborers as part of the Saudi Vision 2030’s aims for ‘Saudization’ of the labour force – in the years to come the loss of these remittances to Yemen, currently the country’s largest source of foreign currency, will cause untold hardship and undoubtedly reignite socioeconomic instability and conflict.

Whatever the outcome of the Riyadh Agreement, history will remember that Yemeni government and STC leaders alike smiled at the cameras and hailed the Riyadh Agreement as a triumph. These men who denounce the Houthis as Iranian proxies themselves celebrated signing over the country’s sovereignty, and their own legitimacy and authority, to a foreign power.

Contents

- Riyadh Picks Up the Pieces

- Other Political Developments

- Military and Security Developments

- Economic Developments

-

Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments

- UN Pressures Houthi Authorities on Humanitarian Access in Northern Yemen

- Fuel Shortages Blamed for Water Crisis, Delays in Aid Distribution

- War Data Project Estimates Direct-Conflict Deaths at 100,000-plus

- Report: Systematic Torture, Rape of Migrants Openly Trafficked in Yemen

- Court Seizes Assets of Baha’i Detainee

Developments in Yemen

Riyadh Picks Up the Pieces

Yemen’s internationally backed government and the Southern Transitional Council (STC) signed an agreement November 5 in the Saudi capital, Riyadh, intended to end their recent power struggle in southern Yemen.[1] As part of the accord, known as the Riyadh Agreement, the STC will be given seats in a newly formed Yemeni government composed of political technocrats, as well as a seat at the negotiating table during any future peace talks. In exchange, all STC-aligned military forces will be placed under the authority of the interim government’s Ministry of Defense and STC-aligned security forces under the Ministry of Interior. Brokered during weeks of talks in Jeddah and signed in Riyadh, the deal also calls for returning the Yemeni government to its interim capital of Aden and reactivating all Yemeni government institutions.

Saudi Arabia, along with its partner in the coalition, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), had called for reconciliation talks in August shortly after the STC staged a coup and routed the government from Aden. Major power brokers who attended the ceremony included Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Emirati Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayad, Yemeni President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi and STC leader Aidarous al-Zubaidi.

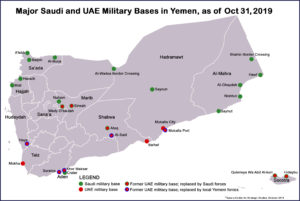

The Riyadh Agreement also reaffirmed Saudi Arabia’s role as the primary actor in the military coalition,[2] assuming military responsibilities in the anti-Houthi coalition that had previously been held by its partner, the UAE. Tension had increased between Riyadh and Abu Dhabi over fighting in the south between Saudi-backed Yemeni government forces and those aligned with the Emirati-backed STC. However, a breakthrough appeared to come following an October 6 meeting between Emirati Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayad and Deputy Defense Minister Khalid bin Salman.[3] The agreement grants Saudi Arabia security responsibility for Aden and other southern governorates as well as overall control of the integrated military and security forces in the anti-Houthi coalition.

This process had been occurring throughout the month of October, before the actual signing of the agreement, with Saudi reinforcements arriving in Aden and other southern governorates and assuming security control from withdrawing Emirati forces. The General Command of the UAE Armed Forces announced October 30 that Emirati troops had ended their deployment in Aden governorate and had handed over security responsibility to Saudi Arabia and the Yemeni government. Emirati troops, in cooperation with allied forces, would continue the “war on terrorist organizations” in Yemen’s southern governorates, the statement added.[4]

The UAE had established a heavy military presence in Yemen’s southern governorates and on the Red Sea Coast since entering the conflict in 2015 as a key part of the Saudi-led coalition. In June, Sana’a Center sources within the anti-Houthi forces in the Red Sea city of Mokha reported that the UAE was undertaking a large-scale removal of its military assets and personnel, including armored vehicles, tanks, radar installations, and helicopters. This was followed by the UAE drawing down troops in both Marib and Hudaydah governorates.[5]

The Aden pullout began earlier in the month, with Reuters reporting on October 8 that an Emirati convoy of military vehicles and at least 200 troops had departed the city via a vessel from Buraiqa oil terminal.[6] Yemeni government officials told The Associated Press that 15 Saudi military transport aircraft landed in Aden on October 24, carrying troops, tanks and other military equipment.[7] The officials also said Saudi reinforcements had arrived in Shabwa and Hadramawt governorate, apparently in line with the Riyadh Agreement. The UAE Red Crescent also suspended activities in Aden, according to a former media officer for the organization who said it would leave a “huge vacuum” in healthcare provision and other humanitarian efforts in the city and other southern governorates.[8]

Analysis: Saudi Arabia Takes the Helm in Southern Yemen

The most important aspect of the Riyadh Agreement is that, if fully implemented, Saudi Arabia will assume ultimate responsibility for southern Yemen politically, militarily and in terms of security, with the United Arab Emirates relinquishing its authority over its Yemeni proxies there. UAE-backed proxy forces across south Yemen are to be absorbed into government military and security units, with the new unified chain of command and control ultimately responsible to the Saudis. The apparent aim: to create a unified front to challenge the armed Houthi movement for control of northern governorates… [Read a full analysis here of the Riyadh Agreement by the Sana’a Center co-founder and executive director, Maged al-Madhaji.]

Other Political Developments

Houthi Partial Cease-Fire Holding, De-escalation Efforts Continue

A unilateral cease-fire by the armed Houthi movement from drone and missile operations on Saudi soil appeared to be holding, with no such cross-border strikes reported through October. The Houthis had threatened on October 3 to resume strikes if Riyadh ignored the cease-fire overture, according to Al-Masirah TV.[9] The next day, Saudi diplomatic sources told Reuters that Riyadh had significantly decreased airstrikes in Yemen since the Houthis’ offer and that the kingdom was seriously considering a deal to de-escalate the conflict.[10] Saudi Deputy Defense Minister Khalid bin Salman, said October 4 that Riyadh viewed the ceasefire “positively.”[11]

Mahdi al-Mashat, head of the Houthis’ Supreme Political Council, announced the unilateral cease-fire after Houthi forces claimed responsibility in mid-September for attacks on Saudi oil facilities that temporarily knocked more than 5 percent of the world’s crude production offline. Senior Houthi officials and international diplomats later confirmed to the Sana’a Center that after the announcement Al-Mashat and bin Salman spoke by telephone, initiating a channel for direct communication.

Houthis Release Detainees Accused of Failed 2011 Assassination Plot, Angering GPC

The October 18 release of at least 20 prisoners in Houthi custody, including five individuals accused of attempting to assassinate former President Ali Abdullah Saleh in 2011, stoked an angry response among members of the late president’s political party. The prisoner exchange with the Islah party took place in Al-Jawf governorate and also included a number of activists from the 2011 Yemeni revolution, according to a report by Al-Masdar.[12] Five of the released prisoners were arrested after the June 2011 bombing of a mosque in the presidential compound in Sana’a, which wounded Saleh.[13] The five suspects released were never tried or convicted. The armed Houthi movement released 14 detainees as part of the exchange while the Islah party handed over 10 prisoners.[14]

In response to the release, the Sana’a branch of the General People’s Congress (GPC) – the party of the former president – announced on October 20 that it would boycott all future work in Houthi governing institutions, including the Supreme Political Council and the Shura Council.[15] The walkout lasted six days. During a meeting on October 26, the GPC President in Sana’a, Sheikh Sadiq Amin Abu Ras, and Mahdi al-Mashat, head of the Houthis’ Supreme Political Council, discussed the disagreement and stressed the need to maintain unity between the parties.[16] Saudi media alleged that the reversal followed Houthi threats to GPC officials.[17]

Other Political Developments in Brief:

- October: Protesters demanded less corruption, better public services and the replacement of the current local authority during popular demonstrations throughout the month in Taiz city.[18] On the security front, the protesters also pushed for the opening of humanitarian corridors and for reopening supply routes from Taiz to Aden currently controlled by Houthi forces.

- October 12: The Ministry of Education of the internationally recognized Yemeni government lashed out at Qatar over the state-backed Qatar Charity’s decision to finance the printing of new school textbooks in Houthi-held areas, saying it was participating in “poisoning the mind of the Yemeni student.”[19]

- October 17: A Houthi-run court issued subpoenas for a number of world leaders over alleged war crimes in Yemen. The list of 124 individuals, published by Al-Thawra newspaper, included US President Donald Trump, former President Barack Obama, former British premiers David Cameron and Theresa May, Saudi King Salman, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, president of the internationally-recognized Yemeni government Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, among others. The court, whose legitimacy is not recognized beyond the Houthi authority, threatened to try in absentia persons who did not heed the summons.[20]

Military and Security Developments

Sudanese Troops Pulling Out of Yemen

Sudan has withdrawn “several thousand” of its troops stationed in Yemen as part of the Saudi-Emirati-led coalition, The Associated Press reported October 30. The departing troops, mainly from the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), have left in recent months, two senior Sudanese officials told the AP.[21] The head of the RSF, Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, had agreed with Saudi Arabia that the withdrawn forces would not be replaced but that several thousand Sudanese soldiers would remain in the country to train Yemeni government forces. The officials said Sudanese troop levels in Yemen had peaked at 40,000 in 2016-2017.

Reports of Sudan withdrawing troops from Yemen, mainly from the Hudaydah governorate, first circulated in July.[22] General Abdul Fattah al-Burhan, chairman of Sudan’s Transitional Military Council following the ousting of longtime Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, claimed in a July 30 interview that no withdrawal was taking place and that Sudanese forces would remain in Yemen.[23] However, the Sana’a Center reported at the time that the July redeployments were made in preparation for a full Sudanese withdrawal from Yemen by the end of the year.

STC, Yemeni Government Forces Ally in Al-Dhalea, Feud in Abyan

STC-aligned Security Belt forces and Yemeni government troops advanced against Houthi forces in Al-Dhalea governorate in October. According to a military spokesperson for the Southern Joint Forces who spoke with The National, the combined anti-Houthi forces commenced attacks on three axes on October 8. Capt. Majed al-Shoueibi was quoted as saying the offensive pushed the Houthis out of 80 percent of northern Al-Dhalea and allowed the Southern Joint Forces to capture the strategic Al-Fakhir area, west of Al-Qataba district, which links Al-Dhalea to neighboring Ibb governorate.[24] Houthi forces counterattacked on October 11 with reinforcements brought in from Ibb,[25] and fighting in the western part of Al-Dhalea continued into November.[26]

Meanwhile on October 31 in nearby Abyan governorate, the Ahwar district saw fighting between STC- and Yemeni government-affiliated forces that left six dead on both sides, according to medical sources quoted in a Xinhua report. Yemeni government forces captured the district from STC forces and local tribesmen who joined the fighting alongside the STC.[27]

Houthi Forces Make Further Military Gains in Sa’ada

Houthi forces launched an offensive in Sa’ada governorate in late October against Yemeni government troops. Houthi forces captured most of Al-Malaheeth region following a major offensive against coalition forces, which included the Yemeni Al-Arouba Brigade and Saudi troops, according to a Yemeni government soldier who spoke with the Sana’a Center. According to a report by Al-Masdar, Houthi forces captured around 40 positions from the coalition near the Al-Malaheeth front, on the border with Saudi Arabia’s Jizan province and seized the road linking the area with Al-Mazraq in neighboring Hajjah governorate.[28] The report claimed many casualties on the coalition side.

The latest round of fighting in Sa’ada governorate, the stronghold of the Houthi movement, came after Houthi forces claimed in September to have destroyed three government brigades and captured over 2,000 soldiers in an August operation near the Saudi-Yemeni border.[29] That battle centered around Sa’ada’s Kitaf region.

Military and Security Developments in Brief:

- October: Pro-STC forces organized demonstrations and sit-ins during the month demanding the removal of the governor of Socotra, Ramzi Mahrous.[30] Mahrous and pro-Hadi forces have accused Emirati troops and Security Belt forces of attempting to stage a coup in the governorate amid reports that the UAE has sent additional weapons and military cargo to island.[31]

- October 10: US President Donald Trump confirmed that suspected Al-Qaeda bombmaker Ibrahim al-Asiri was killed in a US counterterrorism operation in Yemen two years ago.[32] Al-Asiri was allegedly involved in the failed “underwear bomb” plot on a US-bound airliner on Christmas Day, 2009. He was also accused of having built explosive devices disguised as printer cartridges used in another transatlantic aircraft bomb plot in 2010. The latter attack was foiled following a tip-off from Saudi Arabia’s Prince Mohammed bin Nayef, then a senior Interior Ministry official.

- October 29: An explosion struck a convoy of vehicles used by Defense Minister Mohammed al-Maqdishi at the ministry’s headquarters in Marib governorate. At least one person was killed and one injured, with casualty reports varying up to two dead and four wounded.[33] A source close to the defense minister told the Sana’a Center a surface-to-surface missile struck while a high-level meeting between Yemeni and Saudi officials was taking place. Senior officials were not among the casualties, he indicated, adding that one person has been arrested for leaking information that led to the strike.

- November 1: A suspected drone strike in Raydan, Marib governorate, killed two alleged AQAP members, Khamis bin Arfaj, a commander in the organization, and his brother, Turki bin Arfaj.[34]

- November 1: Houthi movement spokesperson Yahya Sarea claimed the group had shot down a US-made drone, known as the Scan Eagle, along the Yemeni border with the Saudi province of Asir.[35]

Economic Developments

SAFER Preparing to Export Crude Oil via Shabwa

The internationally recognized Yemeni government began transporting crude oil in October from the state-run energy company, Safer Exploration and Production Operations Company (SEPOC), more commonly known as SAFER, in Marib governorate in preparation for export from the Nashima terminal located south of Belhaf in Shabwa governorate.[36] As reported by the Sana’a Center in May 2019, the government had been trying to secure the delivery of crude oil from the point of production in Marib to an existing pipeline that starts in Shabwa’s west Ayyad and runs to the Nashima export terminal.[37] Currently the oil is being trucked overland but a Chinese company is looking to construct a pipeline that would ensure the quick transport of crude oil the entire way.[38] Currently an estimated 8,000 barrels per day (bpd) is being produced and trucked to west Ayyad.[39] Some government officials estimate that in the coming months the amount will increase to up to 16,000 bpd.[40]

In a sign of the challenges the plan faces, however, the pipeline in Shabwa was targeted by unidentified assailants in two separate incidents in October. The first explosion occurred on October 7 south of the governorate capital of Ataq.[41] A second explosion on October 27 targeted the pipeline in Rawdah district.[42] No group claimed responsibility for the blasts, but previous similar attacks in the region have been carried out by Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

Yemeni Finance Minister Seeks International Aid to Address Budget Deficit

Yemen requires increased international financial support to help close its 2019 budget deficit of $2 billion, Finance Minister Selim bin Breik told an annual meeting of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in Washington.[43] Bin Breik was speaking October 21 at an IMF gathering of finance ministers and central bank governors from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

The significance of Bin Breik’s remarks are heightened by growing concern about the depleting amount of funds left from the $2 billion deposit Saudi Arabia made in the Aden central bank in January 2018. The central bank has been using the Saudi money to underwrite the import of five essential commodities (rice, wheat, sugar, milk and cooking oil) since June 2018. According to one senior banking official, roughly $1.4 billion of the Saudi deposit has been spent, with a further $300 million in process to be used to cover the next scheduled batch of food import applications.[44] Once processed, this would leave approximately $300 million from the Saudi deposit, which is expected to be exhausted by mid-January 2020.[45] Without additional outside aid, when the Saudi financing runs out the Sana’a Center economic unit estimates the Yemeni rial will quickly lose more than half its current value against the US dollar.

Houthis Release IBY General Manager

In late October, the general manager of the International Bank of Yemen (IBY), Ahmed Thabet, was released after almost three months of detention in Sana’a, three banking officials told the Sana’a Center.[46] Local media previously claimed Thabet had been detained by Houthi authorities after refusing to provide bank funds to the movement.[47]

Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments

UN Pressures Houthi Authorities on Humanitarian Access in Northern Yemen

The UN Humanitarian Coordinator in Yemen is pressuring Houthi authorities on restrictions to humanitarian response in areas under their control. Lise Grande sent a letter to Houthi authorities on October 9 calling for an end to administrative constraints that the UN body says are stopping aid from reaching those in need. These included restricting freedom of movement for humanitarian personnel and impeding needs assessments — including those that are used to determine famine classifications.

The letter also pushed back on efforts to place conditions on organizations that are either seeking to work in Houthi-controlled areas or renewing their approvals — conditions it said could undermine the ability of humanitarian actors to maintain impartiality. Houthi authorities have sought to apply similarly compromising conditions to agreements at the project level, which are also subject to lengthy delays; the latest data indicates that at least 56 projects are still pending in Houthi-controlled areas, affecting 4.3 million people.

OCHA chief Mark Lowcock highlighted problems surrounding humanitarian access in Yemen in his briefing to the UN Security Council on October 17.[48] Lowcock said the Houthis have introduced more than 100 directives that organizations must comply with while contending with harassment and persistent attempts at interference. He added that the Houthis refused entry to UN personnel — including a senior official — in September.

Fuel Shortages Blamed for Water Crisis, Delays in Aid Distribution

Humanitarian organizations warned in October that deepening fuel shortages in Houthi-controlled northern Yemen had delayed humanitarian aid and prompted a clean-water crisis. By month’s end, the immediate crisis had eased with the offloading of several fuel ships caught up in a dispute between Aden- and Sana’a-based authorities over customs and port fees. International NGOs, anticipating further such crises, called for the internationally recognized government and Houthi authorities to stop using fuel as a tool of war.

Save the Children said October 9 that the fuel shortage had delayed its deliveries of food and medical supplies and had prevented hospitals from receiving diesel to run their generators.[49] Its director, Tamer Kirolos, said shipments that should have taken one day required three as trucks waited for fuel. Save the Children and the Norwegian Refugee Council expressed concern that cholera, which the NRC said in its October 16 statement had killed nearly 1,000 people in Yemen this year, could worsen for lack of safe water for drinking and sanitation.[50]

Oxfam reported October 22 that fuel shortages had severely cut clean water supplies to 15 million people since September, 11 million of whom rely on piped networks and 4 million of whom depend on water being trucked in by private companies. Central water systems, it said, had to be shut down during the crisis in the cities of Ibb, Dhamar and Al-Mahwit, affecting about 400,000 people. Piped water systems Oxfam installed that supply about 250,000 people ran at half capacity, the group said, adding that the fuel crisis also had forced it to cut trucked water to thousands more.[51]

Prices of staple foods were also affected, with 50 kilogram sacks of flour rising from 11,000 rials to 14,000 rials in Sana’a during the crisis before falling back to about 10,400 rials. Sana’a residents relying on trucked water saw prices rise from 5,000 rials per 1,000 liters to as high as 15,000 rials before normalizing. Fuel prices in the city were roughly 1,000 rials per liter on the black market, well above the official rate of 365 rials per liter, and the NRC said petrol stations either closed or so limited their hours that, at their peak, lines stretched several kilometers with waits of two to three days. Later in October, as more fuel came into the market, it was possible to buy at official prices and Sana’a petrol stations were crowded but moving. Oxfam also reported water distribution in urban areas returning to normal, but said in early November that rural areas were still struggling. The organization added that it anticipated further severe fuel shortages in the coming month.[52]

Save the Children and the NRC separately cited a need for the internationally recognized Yemeni government to lift regulations on fuel imports so supplies could enter the country without interruption. Kirolos, of Save the Children, called for “free, unhindered access for humanitarian and commercial goods, including fuel, into and across the country as this is a life-line for many families.”[53] Oxfam condemned the fuel crisis as “the latest example of the warring parties using the economy as a weapon of war.” It blamed the dramatic escalation to the usual fuel shortage issue on additional import restrictions imposed by the internationally recognized government but said that Houthi authorities also imposed restrictions.[54]

Importers are required to pay government-mandated fuel import taxes and customs fees in Aden before ships are allowed to offload fuel in Hudaydah, but Houthi authorities have refused to allow port entry to ships that pay the fees. Importers also are frustrated by having to pay twice – once to the government in Aden and again to the Houthi authorities in Sana’a – in order to ship fuel to the more populous northern areas (see ‘New Fuel Crisis Causes Price Spikes’, The Yemen Review, September 2019’).

The latest fuel crisis began to subside after 10 vessels were given waivers by the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the Saudi-led coalition before proceeding to the Houthi-controlled docking area where they berthed and unloaded; by the end of October, three of the 10 vessels given waivers remained at anchorage.[55] This should allow enough fuel to meet market demands for three-to-four weeks, but the situation beyond that remains uncertain. Eight more vessels remained in a coalition holding area[56] as of October 31 with fuel merchants reluctant to pay the fuel import taxes and customs fees to the government that were, as of the end of September 2019, being deposited in the central bank branch of Hudaydah.

War Data Project Estimates Direct-Conflict Deaths at 100,000-plus

More than 100,000 Yemenis have died in direct conflict since 2015, according to an estimate published October 31 by an organization that aggregates data in war zones. The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) said the figure included 20,000 direct-conflict deaths in 2019. Attacks on civilian targets since 2015 have killed more than 12,000 civilians, according to ACLED, which noted the true civilian toll would be higher because the figure did not include civilian deaths considered as collateral damage to military strikes and actions.[57] The United Nations humanitarian coordinator, Mark Lowcock, meanwhile, told the UN Security Council on October 17 that September had been the deadliest month thus far in 2019 for civilians, with 388 killed or injured due to conflict. He noted there were more than 30 active frontlines.[58]

According to ACLED, Taiz governorate has seen the most direct conflict deaths through the war, with 19,000 since 2015, despite a decline in violence there in 2019; Hudaydah and Al-Jawf followed with about 10,000 fatalities in each governorate since 2015.[59] ACLED, which notes it uses the most conservative reports of direct conflict fatalities, does not count indirect causes of death linked to the war, including starvation and disease.

Muhsin Siddiquey, the country director in Yemen for Oxfam, said the ACLED figures should serve as “a wake up call to all sides” and noted the true death toll was much higher when deaths related to lack of medicine, food and clean water were included.[60] A UNDP report released earlier this year estimated the number of such indirect conflict deaths would reach 131,000 by the end of 2019,[61] bringing the estimated overall figure to more than 230,000 people dead.

Report: Systematic Torture, Rape of Migrants Openly Trafficked in Yemen

Hundreds of Ethiopian migrants passing through Yemen on their way to seek work in Saudi Arabia are being waylaid in Ras al-Ara, Yemen, where human traffickers detain, torture, starve and systematically rape them while extorting money from their families back home, The Associated Press reported October 30.

Yemeni and Ethiopian traffickers work together, transporting the migrants openly through military checkpoints as Yemeni authorities largely ignore the imprisonment and torture, AP reported. It quoted a former coast guard officer as saying the traffickers move freely in public, paying bribes at checkpoints. The AP quoted an unidentified humanitarian worker who monitors the flow of migrants as estimating 800 out of every 1,000 migrants disappear into the lockups during their journey. On a single day, AP reported seeing more than 700 migrants come ashore.[62]

Abuse of migrants moving through Yemen is not new; a 2014 Human Rights Watch report spoke of the use of torture and extortion against migrants flourishing in 2006 in Harad district in Hajjah governorate near the border with Saudi Arabia.[63] A humanitarian worker, who spoke to the Sana’a Center on condition of anonymity, has been interviewing child victims of torture since 2015. She spoke of a migrant boy whose family was unable to pay, saying he was hung by his hand while locked up. On eventually being released, his hand had to be amputated, she said.[64]

Shortly after the AP report, on November 1, the International Organization for Migration released a statement noting the “perilous journey to and through Yemen” faced by migrants from the Horn of Africa.[65] IOM estimates at least 160,000 migrants will have entered Yemen by the end of 2019, including many unaccompanied or separated children.[66] “Migrants on the route to Yemen are amongst some of the most vulnerable, and meeting the humanitarian needs of this population must remain a priority for the international community,” Mohammed Abdiker, the IOM regional director for the Horn of Africa, said in a fund-raising appeal aimed in part at providing urgent humanitarian assistance to migrants stranded in Yemen.[67]

Court Seizes Assets of Baha’i Detainee

A Houthi-run court on October 22 ordered the money and property of a Baha’i man on death row to be seized in a case condemned by human rights organizations as part of the systematic persecution of Yemen’s Baha’i religious minority. The move came in the latest hearing for Hamed bin Haydara, an independent human rights organization that has been monitoring the case told the Sana’a Center.[68] A Houthi-run court sentenced Bin Haydara, a leader in the Baha’i community, to death in January 2018.

International human rights groups have condemned the persecution of Yemeni Baha’i, who are believed to number more than 1,000, first by the Yemeni government pre-2014 and later by Houthi authorities who took over Sana’a (see ‘In Focus: Persecution of Baha’i Religious Minority in Yemen, The Yemen Review – March 2019’).[69] The US Commission on International Religious Freedom, a bipartisan government-appointed commission, raised concern October 13 that the Houthis appeared to be appraising assets of the Baha’i community in general and expressed concern they may confiscate assets and deport Yemeni Baha’is.[70] The UN Human Rights Council called in September for the immediate release of all Baha’i detained in Yemen for their religious beliefs and to “cease the harassment and judicial persecution to which they are subjected.[71]

International Developments

At the United Nations

Progress Emerges on Aspects of the Stockholm Agreement

After 10 months of little progress, October saw movement related to carrying out provisions of the December 2018 Stockholm Agreement, reached between the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the armed Houthi movement. As part of the UN-backed de-escalation accord, both the Yemeni government and the Houthi movement had committed to a cease-fire in Hudaydah governorate, a prisoner exchange and a statement of understanding to discuss de-escalation in the city of Taiz.

In a unilateral move, the Houthis released 290 detainees on September 30, and on October 11 announced that they had a new prisoner swap proposal on offer to the Yemeni government involving 2,000 detainees in a “first phase.”[72] Abdul Qader al-Murtada, head of the Houthis’ prisoner affairs committee, called on the government to respond in kind. Hadi Haig, his counterpart on the Yemeni government’s side, denied on the same day receiving any formal offer.[73]

The new initiative appears to be the latest Houthi attempt to signal to the Yemeni government and its Saudi backers the group’s ability to compromise as well as to revive the prisoner exchange aspect of the Stockholm Agreement. Intended as a confidence-building measure, the proposal envisioned the release of about 7,000 prisoners from each side. However, despite exchanging proposed lists of names in January, the Houthis’ unilateral prisoner release in late September was the first move characterized as a step toward fulfilling what was agreed to in Sweden. The International Committee of the Red Cross, which facilitated that September 30 release, confirmed that 290 Yemenis had been freed from Houthi custody.[74]

On the Hudaydah front, the Redeployment Coordination Committee – the tripartite UN, Houthi and Yemeni government body charged with establishing mechanisms for the demilitarization of Hudaydah City – established four joint observations posts “designed to facilitate direct inter-party de-escalation in flash point areas” along the city’s frontlines.[75] The UN reported a reduction in cease-fire violations last month in the strategic port city, which serves as the entry point for most of Yemen’s basic goods and humanitarian supplies.[76]

On Taiz, UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths told the UN Security Council during an October 17 briefing that the warring parties had offered to open humanitarian corridors to the city.[77] Local efforts independent from the United Nations were advancing in Taiz, with the former governor, Shawki Hayel Saeed, leading mediation efforts between the Houthis and the Yemeni government in the city. The role played by Saeed – who hails from a prominent Yemeni business family and owns one of the biggest banks in the country – provides an example of how well-connected businessmen in the country can influence outcomes in the conflict.

The constructive responses toward implementing the three main aspects of what was agreed to in Stockholm – after months of general inactivity and intransigence – comes amid reports of a broader de-escalation effort between Saudi Arabia and the Houthi Movement (see: ‘Houthi Partial Cease-Fire Holding, De-escalation Efforts Continue’). The Special Envoy appeared to use this detente to advocate for jumpstarting aspects of the Yemeni peace process. He visited Sana’a for two days on October 1, following the Houthis’ release of the 290 detainees, where he held a meeting with the Houthi leader, Abdelmalek al-Houthi.[78] On October 17, Griffiths traveled to Riyadh for talks with Deputy Defense Minister Khalid bin Salman on mediation efforts between the Yemeni government and the STC related to southern Yemen.[79] The envoy revisited the Saudi capital on October 24 for a second meeting with bin Salman focused on ways to support the political process in Yemen and the implementation of the Stockholm Agreement. The envoy then traveled again to Sana’a on October 23 for a second meeting with Abdelmalek al-Houthi.[80]

Attempt to Have Eminent Experts Brief Security Council is Rebuffed

A UN-appointed panel that has investigated alleged war crimes in Yemen met informally October 18 with members of the UN Security Council after some council members objected to a formal briefing. Security Council Report, an independent organization that monitors and analyzes Security Council activities, said only that “certain council members” plus Saudi Arabia and the UAE had pushed back against a formal briefing by the chairman of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen.[81] The group has reported violations from all warring sides, and its mandate was extended by a year in September.

During their visit to New York, the Eminent Experts told the Sana’a Center that UNSC member states had been generally supportive of their work, but they lamented the lack of cooperation from various actors in the conflict.[82] The group has only been granted access to Yemen once, then the internationally backed Yemeni government refused to grant permission for further visits. The experts expressed pessimism about the prospects for entering in 2020 during a discussion with NGO representatives in New York. While their new mandate has just begun, they also said that one UN member state had suggested delving deeper into crimes related to starvation and denying humanitarian access as a weapon of war in the year ahead as the Security Council has the authority to impose a wide range of measures against perpetrators, including sanctions, under UNSC Resolution 2417 of 2018.[83]

Regional Developments

Pakistan Emerges as Saudi-Iran Go-Between

Saudi Arabia and Iran signaled in early October their interest in a diplomatic solution to the growing tension in the Gulf. Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan traveled to Tehran and Riyadh, apparently acting as a mediator between the regional rivals, who have had no diplomatic relations since 2016.

Khan met with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani on October 13, when the pair discussed tension in the Gulf and the Iran nuclear deal. President Rouhani said he welcomes dialogue to find a solution to “regional issues,” in a joint press conference following the meeting.[84] The Pakistani premier also met with Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei later on the same day. Khan then traveled to Riyadh, where he met with Saudi King Salman bin Abdulaziz al-Saud and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman on October 15. While a report of the meeting in Saudi state media gave little detail regarding the content of the discussions, Khan’s office said the prime minister had called for a peaceful resolution to the regional tension.[85, 86]

Voice of America said that Pakistan’s foreign minister, Shah Mehmood Qureshi, had “hinted” at a possible ceasefire in Yemen in comments to reporters following the meetings, but did not elaborate.[87] Khameini told Khan that Tehran supported an end to Yemen’s war and referred to a “four-point solution” without giving further details – though likely in reference to a peace initiative first forwarded in 2015.[88, 89] Reports on the Riyadh meeting did not say whether the leaders discussed the war in Yemen, which has been suggested as a viable avenue to pursue de-escalation between the US, Saudi Arabia and Iran.[90]

Pakistan’s mediation drive comes on the heels of the September attacks on Saudi oil facilities (see The Yemen Review – September 2019). While the Houthis claimed that they had launched the strikes – which temporarily knocked half of the kingdom’s crude supply offline – Saudi Arabia and the US said Iran was responsible. Despite strong condemnation from the Trump administration, the US response to the attacks was, in the end, more restrained than expected. Though the Department of Defense announced the deployment of almost 2,000 further US troops to Saudi Arabia in mid-October, analysts have suggested that this will do little to assuage Riyadh’s fear that its powerful ally has left it out in the cold.[91, 92] In comments to the Financial Times, a western diplomat said the Aramco attacks were also key to Saudi Arabia’s decision to explore de-escalation with the Houthi movement, explaining that the Yemen war allowed Iran to deflect responsibility for the incident (see ‘Houthi Partial Cease-Fire Holding, De-escalation Efforts Continue’).[93]

In September, Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan said that US President Donald Trump had asked him to mediate between the two countries during a meeting on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly.[94] Khan added that the Saudi crown prince had asked him, during a visit to Riyadh prior to the annual meeting, to speak with Rouhani. Saudi officials, however, told the New York Times that while both Pakistan and Iraq had offered themselves as mediators, the initiative had not come from the kingdom.[95]

Though a close ally and strategic partner of Saudi Arabia, Pakistan did not join the Saudi-led military coalition in 2015. Relations between Islamabad and Tehran are fraught, but Pakistan has generally sought to maintain a neutral stance regionally given its long border with Iran, its own Shia population and longstanding tensions with India.

Regional Developments in Brief:

- October 2: The US State Department published a formal request by the internationally recognized Yemeni government to restrict the imports on artifacts from Yemen. The request, which was received on September 11, was made under Article 9 of the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit, Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.[96]

- October 23: Saudi Arabia reshuffled its Cabinet and appointed Prince Faisal bin Farhan al-Saud as foreign minister, replacing Ibrahim Abdulaziz al-Assaf. Al-Saud was previously Riyadh’s ambassador to Germany and also served a stint as a political adviser in the Saudi embassy in Washington D.C.[97]

- October 26: Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javid Zarif met with Houthi spokesperson Mohammed Abdel Salam in Tehran to discuss the latest efforts to end the conflict in Yemen.[98] Zarif had said on October 8 that Iran would be a “companion” to Saudi Arabia if it ended the war in Yemen and that it supported solving regional problems at the negotiating table.[99]

Former President of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) Ali Nasser Mohammad speaks at the Sana’a Center’s fourth Yemen Exchange conference, held October 21-26 in Beirut, Lebanon.[100] The event saw Yemeni political and tribal figures, economists, security experts, artists and journalists discuss Yemen’s civil war and the local, regional and international actors and dynamics involved with diplomats, scholars and representatives of international organizations. The gathering, which provides a platform for Yemeni voices and a way for participants to deepen their knowledge about the multifaceted nation and conflict, is held regularly, with the next Exchange planned for the first quarter of 2020.

Former President of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) Ali Nasser Mohammad speaks at the Sana’a Center’s fourth Yemen Exchange conference, held October 21-26 in Beirut, Lebanon.[100] The event saw Yemeni political and tribal figures, economists, security experts, artists and journalists discuss Yemen’s civil war and the local, regional and international actors and dynamics involved with diplomats, scholars and representatives of international organizations. The gathering, which provides a platform for Yemeni voices and a way for participants to deepen their knowledge about the multifaceted nation and conflict, is held regularly, with the next Exchange planned for the first quarter of 2020.

In Europe

Germany Loosens Arms Export Restrictions to UAE

Germany’s Federal Security Council, which is in charge of approving German arms exports, has approved the export to the United Arab Emirates of components used to power US-made Patriot missile batteries, German media reported October 4.[101] The decision followed heightened tension in the Gulf due to an attack on Aramco oil facilities in Saudi Arabia mid-September, and a subsequent US decision to deliver two additional Patriot batteries to the UAE. The power generators are to be delivered by the Germany-based Jenoptik Power Systems.

In their coalition agreement of March 2018, Germany’s ruling parties had declared they would no longer approve arms exports to states participating in the Yemen conflict.[102] A loophole in the clause, however, stipulated that this would exclude companies that previously had been issued licenses and could prove that

respective arms exports would remain in the recipient country. This has provided for continued arms exports to members of the Saudi-led military coalition, and as reported by the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine, the UAE alone has been licensed for arms exports worth more than EUR 200 million in the first eight months of 2019.[103]

German arms exports to Saudi Arabia were stopped following the killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018. The UK and France, however, pressured Germany to stop impeding the delivery of German components for joint arms projects (see, ‘Arms Debate Triggers Dispute Between UK and Germany: The Yemen Review, February 2019’ and ‘Germany Extends Saudi Arms Export Ban But Exempts Joint EU Ventures: The Yemen Review, March 2019’).

The Franco-German Council of Ministers renegotiated issues surrounding the export of joint arms projects in October, with Germany and France announcing that an agreement had been reached on October 16 regarding legally binding thresholds on weapons components.[104] Details were not made public. Days prior to the Council of Ministers, Agence France-Presse (AFP) cited French government sources as saying that Germany and France had agreed that the former could only block the export of joint arms projects in cases where more than 20 percent of the components were made in Germany.[105]

This report was prepared by (in alphabetical order): Ali Abdullah, Waleed Alhariri, Ghaidaa Alrashidy, Nicholas Ask, Ryan Bailey, Anthony Biswell, Hamza Al-Hamadi, Maged Al-Madhaji, Farea Al-Muslimi, Spencer Osberg, Hannah Patchett, Sala al-Sakkaf, Victoria Sauer, Susan Sevareid, and Holly Topham.

The Yemen Review – formerly known as Yemen at the UN – is a monthly publication produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. Launched in June 2016, it aims to identify and assess current diplomatic, economic, political, military, security, humanitarian and human rights developments related to Yemen.

In producing The Yemen Review, Sana’a Center staff throughout Yemen and around the world gather information, conduct research, and hold private meetings with local, regional, and international stakeholders in order to analyze domestic and international developments regarding Yemen.

This monthly series is designed to provide readers with contextualized insight into the country’s most important ongoing issues.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover diplomatic, political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Endnotes

- “Yemen war: Government and separatists agree deal to end infighting,” BBC News, November 5, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-50306171.

- Riyadh Agreement, English transcript of the accord as carried by Al-Masdar Online English, November 6, 2019, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/58.

- “Abu Dhabi crown prince, top Saudi defense official discuss military, defense matters,” Retuers, October 6, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-emirates-saudi-security/abu-dhabi-crown-prince-top-saudi-defense-official-discuss-military-defense-matters-idUSKBN1WL0JN.

- “The return of Emirati forces operating in Aden after the successful liberation and securing of the city [AR],” Emirates News Agency, October 30, 2019, https://wam.ae/ar/details/1395302798763.

- Elana DeLozier, “UAE Drawdown May Isolate Saudi Arabia in Yemen”, July 2, 2019, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/uae-drawdown-in-yemen-may-isolate-saudi-arabia.

- “UAE pulls some forces from Yemen’s Aden as deal nears to end standoff – witnesses,” Reuters, October 8, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/yemen-security/uae-pulls-some-forces-from-yemens-aden-as-deal-nears-to-end-standoff-witnesses-idUSL5N26T5VI.

- Ahmed al-Haj, “Yemen officials: Saudi airlift deploys troops, tank to Aden,” The Associated Press, October 24, 2019, https://apnews.com/9925fb89774d47f88a28eb7e74c912fe.

- “UAE Red Crescent suspends its activities in Aden, Yemen [AR],” Anadolu Agency, October 21, 2019, www.aa.com.tr/ar/الدول-العربية/الهلال-الأحمر-الإماراتي-يوقف-نشاطه-في-عدن-اليمنية-/1620902.

- Divya Singh “Yemen’s Houthis say preparing for new strikes on Saudi Arabia, if calls for ceasing hostilities ignored,” The Indian Wire, October 3, 2019, https://www.theindianwire.com/world/yemen-houthi-new-strikes-saudi-arabia-194835/.

- Aziz El Yaakoubi, Stephen Kalim and Lisa Barrington, “Saudi Arabia considering some form of Yemen ceasefire: sources,” Reuters, October 4, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-saudi/saudi-arabia-considering-some-form-of-yemen-ceasefire-sources-idUSKBN1WJ23H.

- Khalid bin Salman, Twitter, October 4, 2019, https://twitter.com/kbsalsaud/status/1179918350887071744.

- “Finally, Ibrahim Al-Hammadi and his friends were released after 8 years of unfair detention for the attempted assassination of Saleh [AR],” Al-Masdar, October 18, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/172902.

- “Yemen’s president Saleh ‘wounded in palace attack,’” The Telegraph, June 3, 2011, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/yemen/8554795/Yemens-President-Saleh-wounded-in-palace-attack.html.

- “Ibrahim al-Hammadi and his colleagues accused of attempting to assassinate Saleh in prisoner exchange deal (names and details) [AR],” Yemen Days, October 18, 2019, https://yemendays.com/posts/373.

- “Sanaa conference announces boycott of the Houthis in protest against the release of five youths of the February Revolution [AR],” Al-Masdar, October 20, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/173005.

- “President Al-Mashat Meets The President Of The General People’s Congress And His Deputy To Discuss Many Issues [AR],” Ansarollah website, October 26, 2019, https://www.ansarollah.com/archives/287996.

- “GPC Officials Rejoin Houthi Institutions After Receiving Threats,” Asharq al-Awsat, October 28, 2019, https://aawsat.com/english/home/article/1964836/gpc-officials-rejoin-houthi-institutions-after-receiving-threats.

- “Taiz .. Demonstrations demand the departure of the corrupt in power and the provision of services and salaries [AR],” Al-Mashhad al-Yemeni, October 26, 2019, https://www.almashhad-alyemeni.com/147878.

- “Yemen denounces Qatar Charity financing Houthi-produced school books,” Arab News, October 12, 2019, https://www.arabnews.com/node/1567826/middle-east.

- “Yemen’s rebel court issues ‘subpoena’ for Donald Trump, Barack Obama, and Mbs,” The New Arab, October 17, 2019, https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2019/10/17/houthi-court-issues-subpoena-for-trump-obama-and-mbs.

- Samy Magdy, “Sudan drawing down troops in Yemen in recent months,” The Associated Press, October 30, 2019, https://apnews.com/d5705f44afea4f0b91ec14bbadefae62

- Shukri Hussein, “Sudanese forces partially withdraw from Yemen [AR],” Anadolu Agency, July 24, 2019, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/sudanese-forces-partially-withdraw-from-yemen-/1540335.

- Ali Mahmood, “Sudanese forces not withdrawing from Yemen’s Hodeidah, spokesman says”, The National, July 25, 2019, https://www.thenational.ae/world/mena/sudanese-forces-not-withdrawing-from-yemen-s-hodeidah-spokesman-says-1.890502.

- Ali Mamood, “Dozens of rebels killed as southern forces make gains on Yemen front,” The National, October 9, 2019, https://www.thenational.ae/world/mena/dozens-of-rebels-killed-as-southern-forces-make-gains-on-yemen-front-1.921170.

- “Houthis launch attack against gov’t-controlled areas in southern Yemen,” Xinhua Net, October 11, 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-10/11/c_138464422.htm.

- “Fierce battles in Dahlea and Lightning Brigades break militia attacks in Al-Fakhir and Battar [AR],” News Yemen, November 6, 2019, https://newsyemen.net/news47666.html.

- “Signing Saudi-brokered deal on Yemen postponed as fighting resumed,” Xinhua Net, October 31, 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-11/01/c_138519163.htm.

- “Ansarallah forces launch large-scale offensive in northern Yemen, capture 40 sites,” Al-Masdar, October 25, 2019, https://www.almasdarnews.com/article/ansarallah-forces-launch-large-scale-offensive-in-northern-yemen-capture-40-sites/.

- “Press conference of the Armed Forces Speaker Brigadier General Yahya Sarea – Operation Victory from God,” Al-Masirah, September 29, 2019, https://almasirah.net/gallery/preview.php?file_id=30579.

- South Yemen Daily Post, Twitter post,“Socotra witness the largest demonstration and sit-in in the history of the island,” October 31, 2019, https://twitter.com/SYDP67/status/1189765728892866560.

- “UAE-backed militia besiege Yemen governor of Socotra amid fears of coup,” Middle East Monitor, October 31, 2019, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20191031-uae-backed-militia-besiege-yemen-governor-of-socotra-amid-fears-of-coup/.

- “Statement from the President,” The White House, October 10, 2019. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/statement-from-the-president-11/.

- “Yemen Officials: Defense Minister Escapes Attack on Convoy,” Associated Press, October 29, 2019, https://www.voanews.com/middle-east/yemen-officials-defense-minister-escapes-attack-convoy.

- “Two suspected al-Qaeda members killed by air strike in Marib,” Al-Muqawama Post, November 1, 2019, https://almawqeapost.net/news/45223.

- “Yemeni rebels claim they have shot down a US-made drone,” The Associated Press, November 1, 2019, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2019/11/01/yemeni-rebels-claim-they-have-shot-down-a-us-made-drone/.

- Sana’a Center interviews with SAFER and government officials, October 31, 2019.

- Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, “An Environmental Apocalypse Looming on the Red Sea — The Yemen Review, May 2019,” June 6, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7504#Economic-Developments-in-Brief.

- Sana’a Center interviews with government and UN officials, October 31, 2019.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Oil pipeline blasted in Yemeni southern Shabwa,” Debriefer, October 8, 2019, https://debriefer.net/en/news-11801.html.

- “Gunmen blow up oil pipeline in southeastern Yemen,” Xinhua Net, October 27, 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-10/27/c_138507466.htm.

- Yemen News Agency (SABA), “Finance Minister: $2 Billion Budget Deficit for 2019,” October 21, 2019, https://www.sabanew.net/viewstory/54890.

- Sana’a Center interview with a senior Yemeni banking official, on October 26, 2019.

- Ibid.

- Sana’a Center interviews with three Yemeni banking officials, October 29 and 31, 2019; Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, “The Southern Implosion – The Yemen Review, August 2019,” September 4, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/8016#Houthis_detain_IBY_GM.

- Al Masdar Online, “Houthis Kidnapp International Bank of Yemen Director in Sana’a,” Al Masdar Online, August 10, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/170191.

- “Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock, Briefing to the Security Council on the humanitarian situation in Yemen, 17 October 2019,” UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, October 17, 2019.

- “New fuel crisis deepens suffering for hungry Yemenis,” Norwegian Refugee Council, October 16, 2019, https://www.nrc.no/news/2019/october/new-fuel-crisis-deepens-suffering-for-hungry-yemenis/.

- “New fuel crisis deepens suffering for hungry Yemenis,” Norwegian Refugee Council, October 16, 2019, https://www.nrc.no/news/2019/october/new-fuel-crisis-deepens-suffering-for-hungry-yemenis/.

- “15 million Yemenis see water supplies cut amid fuel crisis,” Oxfam, October 22, 2019, https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/15-million-yemenis-see-water-supplies-cut-amid-fuel-crisis.

- Oxfam policy adviser’s updates via email, October 31 and November 4, 2019.

- “Fuel shortages deepen crisis in Yemen-Save the Children,” Save the Children, October 9, 2019, https://www.savethechildren.net/news/fuel-shortages-deepen-crisis-yemen-–-save-children.

- “15 million Yemenis see water supplies cut amid fuel crisis,” Oxfam, October 22, 2019, https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/15-million-yemenis-see-water-supplies-cut-amid-fuel-crisis.

- As per vessel tracking data provided to the Sana’a Center on October 31, 2019.

- Ibid.

- “Press Release: Over 100,000 Reported Killed in Yemen War,” Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, October 31, 2019, https://www.acleddata.com/2019/10/31/press-release-over-100000-reported-killed-in-yemen-war/.

- “Amid ‘Positive Indications’, Warring Parties in Yemen Must Stop Hostilities, Restart Talks to End World’s Worst Humanitarian Crisis, Special Envoy Tells Security Council,” United Nations, Meetings Coverage, Security Council, October 17, 2019, https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sc13990.doc.htm.

- “Press Release: Over 100,000 Reported Killed in Yemen War,” Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, October 31, 2019, https://www.acleddata.com/2019/10/31/press-release-over-100000-reported-killed-in-yemen-war/.

- “Reaction to Yemen death toll reaching 100,000 people,” Oxfam, October 31, 2019, https://oxfamapps.org/media/press_release/reaction-to-yemen-death-toll-reaching-100000-people/.

- Jonathan D. Moyer, David Bohl, Taylor Hanna, Brendan R. Mape & Mickey Rafa, “Assessing the Impact of War on Development in Yemen,” UNDP and the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures, 2019, p. 9, https://www.undp.org/content/dam/yemen/General/Docs/ImpactOfWarOnDevelopmentInYemen.pdf.

- Maggie Michael, “Migrants endure rape and torture on route through Yemen,” The Associated Press, October 30, 2019, https://apnews.com/476e15db8b77486e9d157b33f9494b22.

- “Yemen’s Torture Camps Abuse of Migrants by Human Traffickers in a Climate of Impunity,” Human Rights Watch, May 25, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/05/25/yemens-torture-camps/abuse-migrants-human-traffickers-climate-impunity.

- Sana’a Center confidential interview with a humanitarian worker, November 1, 2019.

- “IOM: USD 54 Million Needed in 2019 for Migrant Response in Horn of Africa, Yemen,” International Organization for Migration via Reliefweb, November 1, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/iom-usd-54-million-needed-2019-migrant-response-horn-africa-yemen.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Sana’a Center confidential interview with a human rights monitor following the case, November 1, 2019.

- “The Yemen Review – March 2019, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, April 8, 2019, March 2019 report in The Yemen Review, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7269#In-Focus-Persecution-of-Bahai-Religious-Minority-in-Yemen.

- “USCIRF Raises Alarm Over Reports that Houthi Court in Yemen May Deport Baha’is,” United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, October 13, 2019, https://www.uscirf.gov/news-room/press-releases-statements/uscirf-raises-alarm-over-reports-houthi-court-in-yemen-may.

- “Resolution adopted by the Human Rights Council on 26 September 2019, 42/2 Human rights situation in Yemen,” UN General Assembly Human Rights Council, October 2, 2019, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session42/Pages/ResDecStat.aspx.

- “Yemen’s Houthis offer Saudi-backed government new prisoner swap deal,” Reuters, October

- Hadi Haig, Twitter post, “We have not received anything from that…”, October 11, 2019, https://twitter.com/hadi_haig/status/1182630598004920326.

- “Yemen: 290 detainees were released with the facilitation of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC),” International Committee of the Red Cross, September 30, 2019, https://www.icrc.org/en/document/yemen-290-detainees-were-released-facilitation-international-committee-red-cross-icrc.

- “Note to Correspondents: Statement by the Chair of the Redeployment Coordination Committee, Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Abhijit Guha,” United Nations, October 22, 2019, https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2019-10-22/note-correspondents-statement-the-chair-of-the-redeployment-coordination-committee-lt-gen-%28ret%29-abhijit-guha-scroll-down-for-arabic.

- Briefing of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen to the open session of the Security Council,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, October 17, 2019, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/security_council_briefing_-_17_october_2019_-_as_delivered.pdf.

- Ibid..

- “The Special Envoy for Yemen Arrives in Sana’a,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, October 1, 2019. https://osesgy.unmissions.org/special-envoy-yemen-arrives-sana.

- Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, Twitter post, “Met earlier in #Riyadh with @kbsalsaud,” October 17, 2019, https://twitter.com/OSE_Yemen/status/1184906420782804993.

- Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, Twitter post, “I had a constructive meeting with Abdel Malik Al Houthi,” October 28, 2019, https://twitter.com/OSE_Yemen/status/1188855974507008003.

- “November 2019 Monthly Forecast,” Security Council Report, October 31, 2019, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/monthly-forecast/2019-11/yemen-12.php.

- Sana’a Center discussions with the Group of Eminent Experts at an NGO roundtable, New York, October 18, 2019.

- Ibid.

- “Welcome peace gesture by Pakistan, says President Rouhani alongside PM Imran,” Sanaullah Khan Dawn, October 13, 2019. https://www.dawn.com/news/1510619/welcome-peace-gesture-by-pakistan-says-president-rouhani-alongside-pm-imran.

- “HRH Crown Prince Receives Prime Minister of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan,” Saudi Press Agency, October 15, 2019. https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewfullstory.php?lang=en&newsid=1982879#1982879.

- “Prime Minister Imran Khan’s Visit to Saudi Arabia,” Prime Minister’s Office, Islamic Republic of Pakistan, October 16, 2019. https://pmo.gov.pk/press_release_detailes.php?pr_id=3093.

- “Pakistan: Threat Of Saudi-Iran War Subsiding Due to Diplomacy by Islamabad,” Ayaz Gul, Voice of America October 16, 2019. https://www.voanews.com/middle-east/pakistan-threat-saudi-iran-war-subsiding-due-diplomacy-islamabad.

- “A proper end to the war on Yemen will bear positive effects on the region: Imam Khamenei,”Official website of Iran’s Supreme Leader, October 13, 2019. http://english.khamenei.ir/news/7107/A-proper-end-to-the-war-on-Yemen-will-bear-positive-effects-on.

- “Iran submits four-point Yemen peace plan to United Nations,” Louis Charbonneau, Reuters, April 17, 2015. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-iran/iran-submits-four-point-yemen-peace-plan-to-united-nations-idUSKBN0N823820150417.

- “The U.S.-Iran Off Ramp Goes Through Yemen,” Kevin L. Schwartz, LobeLog, September 30, 2019. https://lobelog.com/the-u-s-iran-off-ramp-goes-through-yemen/.

- “DOD Statement on Deployment of Additional U.S. Forces and Equipment to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,” United States Department of Defense, October 11, 2019. https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Releases/Release/Article/1987575/dod-statement-on-deployment-of-additional-us-forces-and-equipment-to-the-kingdo/

- “Trump Is Sending More Troops to Saudi Arabia,” Bilal Y. Saab, Foreign Policy, October 16, 2019. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/10/16/trump-deployment-troops-saudi-arabia-abandoning-syria-iran-attacks/.

- “Riyadh holds talks with Houthis in effort to break Yemen deadlock,” Andrew England and Simeon Kerr, Financial Times, October 11, 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/0e924804-ec31-11e9-85f4-d00e5018f061.

- “Pakistan’s Khan says he is mediating with Iran after Trump asked him to help,” Michelle Nichols, Reuters, September 24, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-iran-khan/pakistans-khan-says-he-is-mediating-with-iran-after-trump-asked-him-to-help-idUSKBN1W92W0.

- Farnaz Fassihi and Ben Hubbard, “Saudi Arabia and Iran Make Quiet Openings to Head Off War,” New York Times, October 4, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/04/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-iran-talks.html.

- “Notice of Receipt of Request From the Republic of Yemen Government Under Article 9 of the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property,” Federal Register, October 2, 2019, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/10/02/2019-21358/notice-of-receipt-of-request-from-the-republic-of-yemen-government-under-article-9-of-the-1970.

- Stephen Kalin, “Young Saudi prince with Western experienced named foreign minister,” Reuters, October 23, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-saudi-cabinet/young-saudi-prince-with-western-experience-named-foreign-minister-idUSKBN1X22G8.

- “Iran’s FM, Yemeni Houthi official meet in Tehran,” Xinhua Net, October 27, 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-10/27/c_138505801.htm.

- “Iran’s FM says Saudi will be “companion” if ends Yemen war,” The Associated Press, October 8, 2019, https://apnews.com/5190ad26d91f424e9463868acade2701.

- “The Fourth Yemen Exchange Conference Concludes,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 28, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/news/8295.

- “Federal government approves tricky arms export to Emirates [German],” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, October 4, 2019, https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/ausland/bundesregierung-genehmigt-heiklen-ruestungsexport-an-emirate-16416637.html.

- Government of Germany, “Coalition agreement between CDU, CSU and SPD, 19th legislative period [German],” March, 2019, https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/975226/847984/5b8bc23590d4cb2892b31c987ad672b7/2018-03-14-koalitionsvertrag-data.pdf?download=1

- “Federal government approves tricky arms export to Emirates [German],” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, October 4, 2019, https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/ausland/bundesregierung-genehmigt-heiklen-ruestungsexport-an-emirate-16416637.html.

- “Council of Ministers in Toulouse: Germany and France sign agreements for arms exports [German],” Die Zeit, October 16, 2019, https://www.zeit.de/politik/2019-10/ministerrat-toulouse-deutschland-frankreich-abkommen-ruestungsexporte.

- “Germany no longer wants to stop all joint arms deals [German],” AFP via Die Zeit, October 13, 2019, https://www.zeit.de/politik/ausland/2019-10/waffenexport-embargo-deutschland-frankreich-saudi-arabien.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

Former President of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) Ali Nasser Mohammad speaks at the Sana’a Center’s fourth

Former President of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) Ali Nasser Mohammad speaks at the Sana’a Center’s fourth