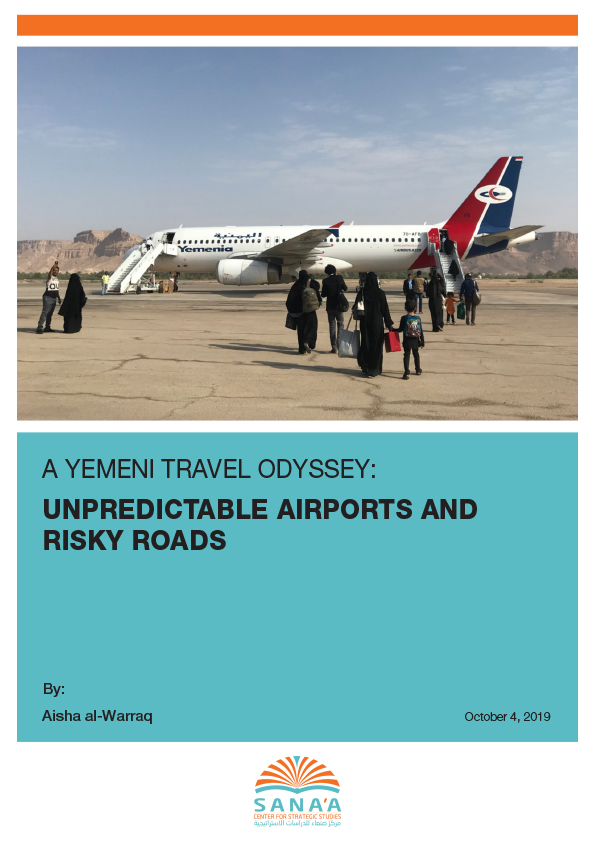

Passengers board a Yemenia airplane preparing to depart on September 8, 2018, from Sayoun International Airport in the Hadramawt governorate, about 600 kilometers east of Sana’a, Yemen // Photo Credit: Sala al-Sakkaf.

By Aisha al-Warraq

Sitting in departures at Queen Alia International Airport in Amman, a backlog of WhatsApp messages ping in upon connecting to the airport Wi-Fi – friends warning me that Aden is risky these days, ready to explode at any moment.

Sitting in departures at Queen Alia International Airport in Amman, a backlog of WhatsApp messages ping in upon connecting to the airport Wi-Fi – friends warning me that Aden is risky these days, ready to explode at any moment.

Trembling, tears come to my eyes. If something happens to me while in Aden, will my family blame me for not telling them that I am traveling? It has been nearly a year since I was last in Yemen; I want to surprise them. And what about my friend who is planning to pick me up at Aden airport and host me for the night before my long journey by road to Sana’a – will that even be possible by the time I arrive? Her home is in an area now surrounded by various armed groups.

Maybe it is best to take a flight back to Frankfurt, return to my flat near campus and cancel this entire plan. But a call to my sister in Saudi Arabia strengthens my resolve; I will travel, no matter what.

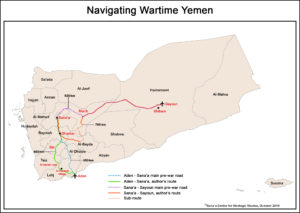

Under the best war-time circumstances, travel to, from and within Yemen is long, tiresome and stressful. There is constant uncertainty about whether airports will be open or closed or how smooth road travel will be through frontlines and scores of checkpoints run by various combatants. Since the Saudi-led coalition stopped commercial air traffic at Sana’a airport in 2016, many Yemenis have been unable to seek medical care abroad; the journey to alternative airports is difficult. My long-awaited trip began August 7, days after deadly twin attacks on police and militia targets in Aden and as southern separatists readied to turn on their government allies in the southern city.

Flights to Yemen operate from only five cities worldwide, with most Yemenis traveling via Amman or Cairo. Flying through Khartoum is more expensive, and flights from Jeddah and Riyadh are used mostly by Yemenis living in Saudi Arabia. On arriving from Frankfurt, I have a 10-hour layover – more than the six-hour minimum required by Yemenia for its passengers transiting through Amman because its flights are regulated by the Saudi-led war coalition, meaning times can change or passenger lists can require verification if non-Yemenis are aboard. Some of my wait is spent explaining to security officers that I need to collect my luggage in the arrivals hall because Yemenia was unable to check my bags through to Aden. As a Yemeni, I need, but cannot be issued at the airport, a visa to enter the arrivals area.

Eventually, I am allowed access to collect my bags. There, I meet a Yemeni woman working with a UN agency. We both are traveling to Sana’a, but her trip will be much different: she is preparing to fly directly to the capital aboard a new UN Airbus and can expect to be in Sana’a by lunchtime. Only humanitarian flights have been allowed in and out of Sana’a airport since 2016, so I will be flying to Aden, spending the night and then setting out on a 14-hour road trip to Sana’a – about twice as long as in peacetime. Back in November 2016, while working for an international agency, I flew into Sana’a aboard a humanitarian flight. I thought about that trip and how I had waited for my taxi after arriving in Sana’a while impatient soldiers urged me to hurry up and leave so they could close the airport. The woman jars me back to the present, asking if I am staying in Aden. Only one night, I say. That’s better, she responds.

Luggage collected and back in departures, I meet a Yemeni woman in her 20s who came to Amman for back surgery. We speak about returning to Yemen – we both have missed our families in Sana’a while abroad and are looking forward to the comforting feeling of being home. We check in and are seated beside each other.

As our plane fills up, many sick or physically infirm passengers – often elderly with traveling companions – make their way to their seats. Some students board and only a few families with children. The mix isn’t surprising. Securing visas is especially difficult for Yemenis, and overseas travel is unaffordable for most, especially after the economic devastation caused by five years of war. But those desperate or determined enough, able to afford it and able to secure visas – often for study or on medical grounds – make the exhausting journey.

One traveler, an elderly woman unable to walk, gazes silently at her son as he and a woman traveling with them try to carry her from the wheelchair down the aisle, struggling with the older woman and their handbags. Flight attendants watch, shouting orders: “Lift her from behind!”, “Hold her legs!” Tears begin to fill the younger woman’s eyes and her voice shakes when she asks them for help that doesn’t come. “Try not to hurt her back!” Between them, they maneuver her into a nearby seat, retrieve their handbags and sit, exhausted, beside her.

As we fly toward Aden, the woman beside me stretches awkwardly, trying to ease her back pain. To my other side, a Yemeni woman from a prominent family speaks of her homes in Amman, Dubai and Saudi Arabia, and of heading home to Ibb with her husband and young sons for the Eid holiday. We land in Aden three-and-a-half hours later in the dusty, humid late afternoon, and I watch the wealthy young family disembark and step into a private car at the base of the airplane stairs.

The rest of us head into the chaotic terminal where airport staff – often impossible to discern from travelers in their street clothes and hoodies – shout and glare at people, eventually stamping our passports. We wait nearly two hours for our luggage, the hall filling with more passengers arriving from Khartoum. Finally, I join my friend who has been waiting outside to take me to her home for the night before my road journey to Sana’a. The tension and anger so palpable at the airport gives way to an eeriness outside, with sounds of distant gunfire and armed soldiers chatting in groups along the way. “People expect fighting at any moment,” my friend tells me.

I sleep early, with plans confirmed to leave early the next morning for the 460-kilometer journey to the capital, Sana’a. The driver collects from their homes three other women heading to Sana’a, and the four of us share the standard US$200 fee. There are cheaper options available; buses cost about US$23, but the journey takes up to four hours longer because of checkpoint delays while passengers are questioned and their papers checked. Some shared taxis pack in more passengers than ours, which can reduce the cost to as low as US$25 per person.

We pass 62 checkpoints along the way, some appearing well-established, others an individual soldier or two briefly stopping and waving through vehicles. At most of them, soldiers or militiamen simply ask where we are coming from and where we are going. At two checkpoints, government-allied soldiers begin arguing with the driver, ordering him to open the trunk and bags inside. He slips them some money and we pass unchecked. As we moved farther north, the questions are similar though the shift of territorial control is clear. Fighters manning checkpoints now mostly dress in civilian clothes, unlike the uniformed soldiers earlier on, and signs appear with the Houthi slogan: “God is Greater, Death to America, Death to Israel, Curse on the Jews, Victory to Islam.” At a checkpoint north of Dhamar, all cars are told to pull over and open their trunks. Our driver knows one of the soldiers, who comes over, pretends to inspect, accepts a “tip” and clears us to travel on.

Residents of Alkala village in the Maghreb Ans area of Dhamar governorate work on September 24, 2019, to clear a road so frequently affected by rain and flooding that the village is accessible only by donkeys // Photo Credit: Saqr Abu Hassan

Our driver knows the unspoken rules and the roads, making the Aden-to-Sana’a journey daily and complaining of lack of sleep, especially with many Eid travelers and people fleeing the tense situation in Aden. The trickiest part of our journey, he says, will be in the southern Taiz governorate, passing through Al-Saylah “road,” which is packed dirt except when rainwater flows through from the surrounding mountains. This 10-kilometer stretch is wide enough for only one vehicle to pass, full of potholes and large rocks; it takes an hour to navigate, more when it rains. We find it muddy from the previous day’s rain, but passable.

We stop twice on our way to Sana’a, pulling over for breakfast along a stretch of road near al-Farshah village in Lahj with two simple restaurants and a small grocery and, later in the afternoon, for lunch in Ibb, a city along our route. My traveling companions are Yemeni-Sudanese aid workers who moved from Sana’a to Aden after the war began, saying they were able to find better opportunities to work with international organizations in Aden than in the now Houthi-controlled north. We pass the time talking about changes they’ve seen in Sana’a on trips back to visit family – more coffee shops opening, they say, as people adapt to life under Houthi rule, and more women are wearing colorful, trendy abayas rather than customary black.

Our driver is from Aden, and his cell phone rings constantly. Usually, it is his father, who calls with the news that fighting has begun in the city. In one of his many updates, he informs his son that an acquaintance has died in the fighting; we offer our condolences and say some prayers. My fellow travelers worry about friends in Aden, texting for information and reassurances. I receive a message that Aden airport has shut down and, not knowing how long it will remain closed, text the travel agency to change my outbound flight from Aden to Sayoun, in the eastern province of Hadramawt and the only other airport in the country currently taking international commercial flights.

As Sana’a approaches, I know that all I need to relieve the headache and back pain from the long car ride is to get home. But it will be one more hour caught in a pre-holiday traffic jam before my 10-year-old brother spots me stepping out from the car. Charging through the front door, he jumps up to hug me. Pulling my bag inside together, we are met by my father, mother, three sisters and sister-in-law hurrying down the stairs, laughing and talking over each other. I pick up my 14-month-old nephew, who – much to my relief – smiles when I hold and kiss him. After much catching up and a retelling of my 54 hours traveling from Frankfurt to Amman to Aden and, finally, Sana’a, midnight is approaching. My parents ask how long I can stay. In 13 days, I explain, I will need to leave. Their eyes tear up as my father says: “We wouldn’t have let you come if we had known you are only going to stay for 13 days – it’s not even worth the travel.”

It is a whirlwind trip full of family, friends and many arrangements, including my engagement and a party to celebrate it – but that’s another story. The days are like a dream, and one I don’t want to leave. Every day, though, I think about my return journey. I know the length of the trip and the type of roads we will travel.

On the morning of August 22, I set out on the 16-hour, 828-kilometer drive through the mountains to Marib and then across a vast stretch of desert to Sayoun, traveling with a colleague who asks many times how much longer our journey will take. Our driver’s standard response: “We still have a lot of time. You will enjoy it.” Neither of us do. I start the journey exhausted and nervous about every checkpoint because my colleague is an unrelated man. At the driver’s suggestion, we make a plan. I will be his aunt. He memorizes my full name and my mother’s name, in case pressed.

In Houthi territory, the driver says “family,” and we are generally waved through with only a cursory question or glance. Checkpoints in government territory are stricter, however, and we are often asked for identification, the purpose of travel and whether we are related. Nobody challenges my colleague’s assertion that I am his aunt. I had been told there may be some Al-Qaeda checkpoints, but to my knowledge we aren’t encountering any – it isn’t always clear who is asking the questions.

With Aden unstable and northerners being turned back at some checkpoints heading south to the city, many other travelers also had shifted their flights to Sayoun. One hotel after another is full. Too tired to argue anymore with the driver, I drop my bags at a dirty, overpriced hostel full of dust and cigarette odor. It costs almost 14,000 Yemeni rials (US$23) for one night – as much as 5-star hotels in the city charge. I call my family, let them know I have arrived safely and try to sleep. Waking up early with a cold, I do what I should have done the day before: I call an acquaintance of a friend who can – and does – find me a clean hotel at a fair price where I can recover before my flight. After a late lunch of chicken and rice and some rest, we visit nearby Shibam Hadramawt, known as the “Manhattan of the Desert” for its towering mud-brick buildings that date back to the 16th century – a nice way to spend my last evening in Yemen.

Shortly before dawn, ticket to Amman in hand, I stand outside the airport doors, waiting for it to open along with the latest group of students, the ill and infirm, a few families and others whose journey, like mine, likely had begun many hours earlier.

Aisha al-Warraq is a researcher and program coordinator for the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. She has worked on food security and child protection issues for various international humanitarian organizations and has contributed to building civil society in Yemen through involvement in programs to empower young entrepreneurs.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية