By: Rafat Ali Al-Akhali & Zaid Ali Basha

Executive Summary

The sustainability of a peace agreement in Yemen depends on two critical economic issues. First, in a conflict that is largely over access to resources, the issues of distribution, control, and sharing of those resources can make or break peace. Therefore, these issues must be addressed head-on during negotiations. Second, where peace agreements lack provisions that create overall economic stability, warfare can resume during the fragile implementation period. The fears over the resumption of conflict after signing a peace agreement are substantiated by several historical events in Yemen, such as the failure of the GCC Initiative.

The sustainability of a peace agreement in Yemen depends on two critical economic issues. First, in a conflict that is largely over access to resources, the issues of distribution, control, and sharing of those resources can make or break peace. Therefore, these issues must be addressed head-on during negotiations. Second, where peace agreements lack provisions that create overall economic stability, warfare can resume during the fragile implementation period. The fears over the resumption of conflict after signing a peace agreement are substantiated by several historical events in Yemen, such as the failure of the GCC Initiative.

At the sixth Development Champions Forum in Amman, Jordan, from January 25 to 27, 2020, the Development Champions therefore focused on identifying urgent macroeconomic, fiscal, and monetary issues that pose a direct threat to the successful implementation of any peace agreement in Yemen. The discussions led to the following key recommendations to Yemeni negotiating parties and international supporters of the peace process on economic provisions that need to be included in the peace agreement:

- Agree on the economic priorities of the post-agreement government, and a process to redefine the state’s economic philosophy within a broader reform agenda and vision.

- Agree on measures to end the division of key state institutions that play a vital role in Yemen’s economy, including the Central Bank of Yemen.

- Establish a socio-economic council mandated with formulating responsive public policies.

- Commit to a transparent, inclusive, and sustainable process for payment of public sector salaries, and agree on a measured approach to the rehabilitation and reintegration of combatants.

- Ensure the smooth, fair, and transparent collection of local revenue and appointment of new heads of public revenue authorities, and put in place an effective accountability mechanism.

- Agree on the allocation of revenue from natural resources.

- Agree on a good governance framework for the reconstruction and recovery process.

- Reopen all seaports, airports, and land border crossings, and lift all restrictions on the movements of goods and travellers through Yemen’s borders.

Contents

- Executive Summary

- Economic Drivers of the Conflict

- The Missing Piece in the Current Peace Process

- Recommendations

- Overarching Economic Provisions

- Public Sector Wages Bill

- The Central Bank

- Collection of Public Revenue

- Reconstruction & Recovery

- Opening Seaports, Airports, & Land Border Crossings, & Lifting Restrictions

- Appendix: Yemen’s Chronic Macroeconomic Drivers of Instability

Economic Drivers of the Conflict

Beyond the ideological drivers, regional dynamics, and political aims of controlling territory and gaining legitimacy, there are crucial economic factors that continue to fuel the conflict in Yemen. To address these economic factors, the Development Champions Forum strongly believes in the importance of including provisions related to the economy in any upcoming peace agreement. The Forum convened its sixth meeting as part of the Rethinking Yemen’s Economy initiative from January 25 to 27, 2020, in Amman, Jordan, where the Forum members discussed the critical economic priorities that should be addressed in the peace process. This policy brief presents the Forum’s insights and recommendations on this topic.

The fighting in Yemen has to a large degree centered around the control of key economic resources and institutions—the “commanding heights” of the country’s economy.[1] The warring parties have been fighting over access to ports; collection of revenue from taxes and customs; production and export of crude oil and liquified natural gas (LNG); regulation of the local currency; channelling of aid inflows; control of key state institutions; and dominance across strategic economic sectors such as telecommunications. Unless the conflict over access to resources is addressed directly and resolved during peace negotiations, historical evidence indicates the heightened potential for renewed violence to erupt soon after a conflict has officially come to an end.

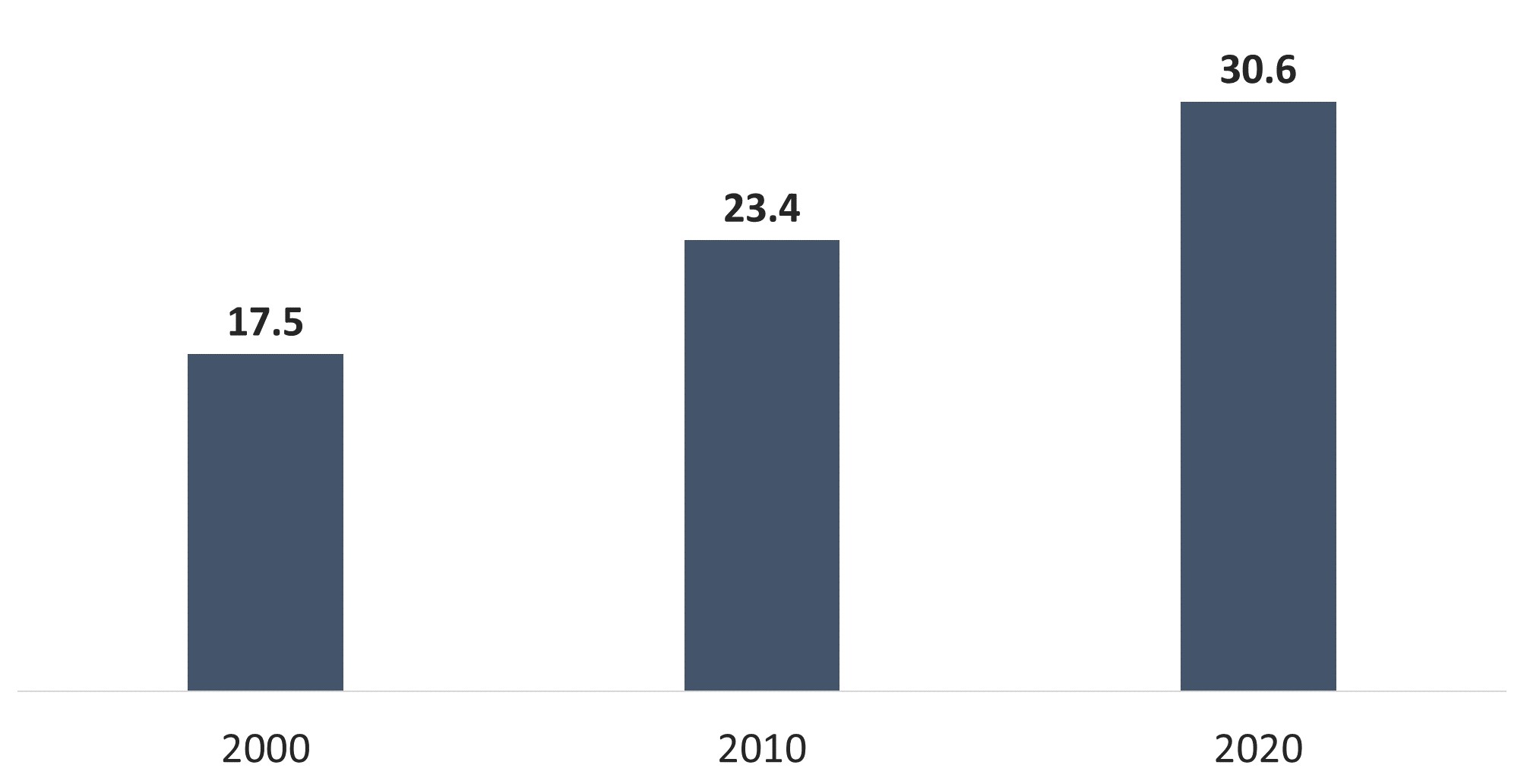

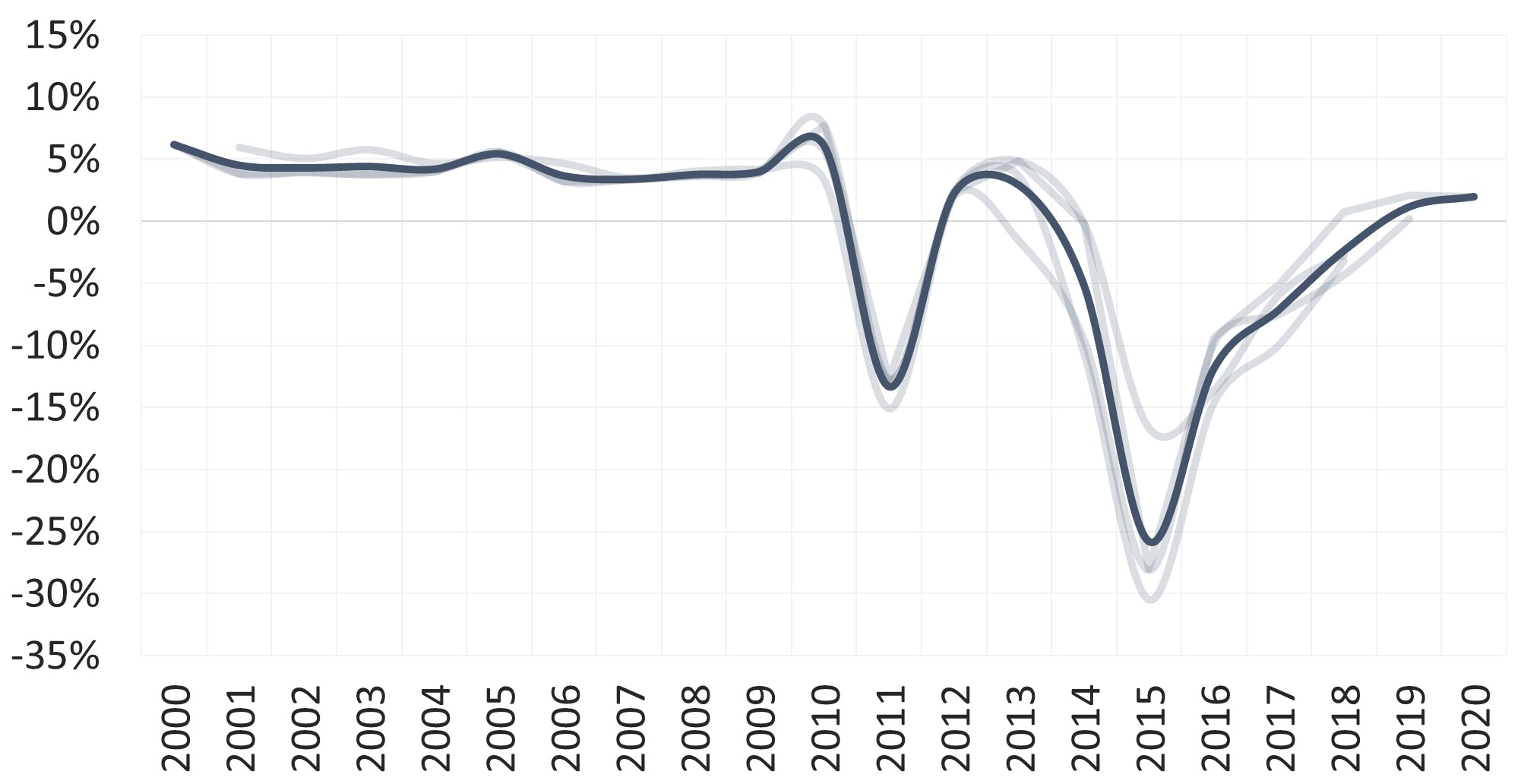

Economic instability in Yemen has been driving social and political unrest over the past two decades. This is evidenced by the growth of Al-Qaeda, country-wide riots against draconian reforms, an armed northern insurgency, mass southern protests, and sweeping demands for political reforms throughout the 2000s, to the vast uprisings, political upheavals, and complex armed conflicts of the following decade.[2] Post-2011, Yemen’s overall economy sustained consecutive devastating shocks, throwing an already impoverished economy into a circle of economic decline. All the while, Yemen’s population has continued to grow exponentially, exploding from around 17 million in 2000 to 30 million in 2020, and its human capital accumulation has continued to regress.[3] Thus, as this growth continues to increase the already dire need for clean water, staple foods, stable income, rural development, essential public services, electricity access, infrastructure, and housing, it will inevitably lead to recurring episodes of upheavals if neglected again. As such, in any upcoming transition process, peace can endure through a cessation of hostilities only inasmuch as the factors that destabilize the economy are addressed. Economic stability is necessary to restore Yemenis’ confidence in the peace process, build up the political capital needed to break the vicious cycle of conflict and fragility, and launch and sustain long term socio-economic transformation and prosperity.

Studies have shown that the parties responsible for the implementation of a peace agreement will immediately be confronted with critical financial and economic issues that stand between peace and war.[4] Generally, research evidence cautions peacemakers and implementers alike that “the period immediately after the signing of a peace agreement is arguably the time of greatest uncertainty and danger.”[5] They point out that the risks of failure of peace agreements are especially likely when they do not result in a reliable roadmap for navigating the imminent hazards of the war-torn post-agreement terrain. Yemen has a recent experience proving this point: following the 2011 protest movement, the GCC Initiative focused heavily on the political and military/security arrangements but largely overlooked the key priorities and processes related to the economy, which contributed to the collapse of the transitional period.

The Missing Piece in the Current Peace Process

Since the conflict started, there have been successive attempts to reach a political settlement. These efforts have been sponsored by the United Nations Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, starting with the talks in Geneva and Biel in Switzerland in 2015, followed by the negotiations in Kuwait in 2016 and the consultations between the government of Yemen and Ansar Allah in Sweden in December 2018, resulting in the Stockholm Agreement. Separately, the Saudi-sponsored Riyadh Agreement between the Yemeni government and the Southern Transitional Council (STC) was signed in November 2019.

The structure of the peace negotiations has been limited to the political aspect and the security/military aspect, with the exception of the UN-brokered consultations convened in Sweden, where one of the consultation tracks focused on the “economic file”, and the resulting Hodeidah Agreement required that “Revenues of the ports of Hodeidah, Salif and Ras Issa shall be channeled to the Central Bank of Yemen through its branch in Hodeidah as a contribution to the payment of salaries in the governate of Hodeidah and throughout Yemen.”[6] But even in Stockholm, the economic issues were only discussed as part of confidence-building measures, and to reach an agreement on steps that would lay the groundwork for peace talks, and not as a main pillar of the future peace agreement in its own right.

There have also been some other initiatives aiming to reach agreements on certain economic issues, such as the efforts to coordinate the work of the Central Bank as a national and independent institution, efforts to pay the salaries of civil servants throughout the country, and finally the efforts to implement the economic clauses of the Stockholm Agreement. But these efforts, as important as they are, are limited to supporting de-escalation and confidence-building; it is not evident yet that the Yemeni parties and international community have firmly embraced the need to include economic provisions that must be agreed upon as an integral part of the peace agreement.

International Experiences in Including Economic Provisions in Peace Agreements

There are several examples of peace settlements that have addressed disputes over economic resources, as part of a wider political agreement.[7] In 1995, the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, also known as the Dayton Agreement or the Dayton Accords, provided for a central bank whose first governing board should consist of a governor appointed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), after consultation with the Presidency, and three members appointed by the Presidency. Of those three appointed members, two were from the Federation—one Bosniac and one Croat, who should share one vote—and a third was from the Republika Srpska, all three of whom should serve a six-year term. The governor, who should not be a citizen of Bosnia and Herzegovina or any neighbouring state, could cast tie-breaking votes on the governing board.

In 2003, the Accra Comprehensive Peace Agreement, or Accra Peace Agreement, which was the final peace agreement in the Second Liberian Civil War, provided specified lists of allocations of ministries and membership of public corporations, at the level of the national government, to the warring factions. It also provided for mechanisms for a Governance Reform Commission to work on good governance, and a new Contract and Monopolies Commission (CMC) to provide for transparency. Each of these bodies had specified membership across conflict divisions including, for example, in the case of the CMC, “five members appointed by the Chairman, on the approval of the NTLA (National Transitional Liberian Authority) from the broad spectrum of society, who may or may not be technocrats.”

In Angola, in an attempt to incorporate non-state armed actors in the new provincial government as a way of demobilizing the conflict, the 2006 Memorandum of Peace and Understanding in Cabinda Province, which provided significant autonomy to the Cabinda province to address conflict there, also enabled economic power-sharing in the form of allocating public corporations to erstwhile armed actors.

The above examples are not necessarily intended to serve as a blueprint for Yemen, but are rather used here to illustrate how other countries have incorporated elements related to the economy within their peace processes and reached agreement on economic-related issues based on what they deemed most suitable for their context. In Yemen, the space needs to be created to allow Yemeni parties to define, negotiate, and agree on their own set of economic-related measures based on the Yemeni context and realities. Unfortunately, and despite the lessons learned from historical cases and other empirical evidence, it is noted that the rounds of political negotiations on Yemen have not yet adequately addressed the economic drivers and consequences of the Yemen conflict.

Recommendations

Overcoming the economic consequences of the ongoing conflict in Yemen will take many years of coordinated efforts among the government, political parties to the conflict, private sector, society, and international partners. Granted, the peace agreement will be primarily a political agreement, and therefore cannot include details on what needs to be done at all levels, but the members of the Development Champions Forum believe that the signatories to the peace agreement must resolve the sticking points that are pivotal to the economy. They believe that key economic issues must be included in the peace agreement, which is important to lay the groundwork for the success of the transitional period after the peace agreement. The following are the most important of these issues:

Overarching Economic Provisions

- Agreeing on the economic-related priorities of the post-agreement government: There must be an agreement on broad outlines of the priorities of the new government’s program. This includes, for example, prioritizing public expenditures that promote economic recovery and stimulate growth, and prioritizing key sectors such as the power sector.

It is imperative that the government’s priorities should not be left out of the political agreement, for that would repeat the fate of the consensus government that was formed after the GCC Initiative. Formed from disparate political parties, the post-2011 consensus government did not get genuine political support for its priorities. As a result, its agenda was disconnected from the country’s political reality at the time, which rendered the new government’s efforts ineffective. Therefore, the political agreement must be clear, not only on how the government is formed, but also on the priorities that it must address. For example, in the case of a reform government, reforms must be identified. Similarly, in the case of a caretaker government, or any other government for that matter, the parameters of its program must be clearly defined so that there is little ambiguity over what it should or should not be doing.

- Ending the division of state institutions: There must be an agreement on clear mechanisms and a time frame to address the division of state institutions, especially those that play an integral role in the economy of Yemen, while committing to working within the scope of these institutions once restored. Creating parallel government structures not only weakens the role of established institutions but also erases their institutional memory, thus preventing the government from building on past achievements.

- Establishing a socio-economic council: The peace agreement should include a provision that leads to the establishment of a council that brings together the government, private sector, and civil society, and mandate it to formulate economic policies. In this regard, previous efforts that ended in 2014 can be benefitted from in the establishment of this council. Whether the council’s policies guide or dictate the government is a decision that needs to be negotiated and agreed on by the negotiating parties.

- Agreeing on a process to redefine the state’s economic philosophy: The period immediately following the peace agreement can provide a unique opportunity for elaborating a new vision for development that avoids replicating the failures of the past[8]—the over-dependence on oil revenues, the marginalization and impoverishment of rural areas, and skyrocketing food trade deficits, to mention only a few examples. The peace agreement can set the stage for this process by including provisions on how to structure this process (e.g., who should be included, timeframe, etc.).

Public Sector Wages Bill

- Payment of public sector salaries: It is imperative for the peace agreement to ensure the payment of public sector salaries in a sustainable manner to maintain service delivery and institutional resilience. Furthermore, the rising wage bill for the public sector, including the military and security apparatus, is a ticking bomb that threatens future economic stability in Yemen. Therefore, the signatories of the agreement shall commit to a transparent and inclusive process for removing double-dippers and ghost workers from the 2014 payroll, and shall agree on a clear and fair mechanism for any additions to the 2014 public sector payroll.

- Rehabilitation and reintegration of combatants: It is often mentioned that additions to the 2014 public sector payroll is mainly required to absorb the large numbers of fighters recruited by the different armed groups. The Development Champions strongly recommend against the blind integration of large numbers into the payroll as the state will struggle to carry the burden of paying additional wages and salaries in perpetuity to an already-bloated public sector when a peace agreement is reached. The Development Champions recommend that the signatories of the agreement commit to developing a national program for the rehabilitation and reintegration of members of armed groups and military formations who were not already included in the 2014 payroll of the Civil Service or the Ministries of Defence and Interior.

The Central Bank

- The administration of the Central Bank: The peace agreement must include a provision to enable the Central Bank to play its essential role and carry out its main functions, in accordance with the law, including agreement on the appointment of its board of directors based on the requirements stipulated in Central Bank Law and respective criteria of competence and integrity.

- Funding channels: The agreement must include a provision requiring all donors to funnel all aid and financial grants through official channels, without the intervention of any political party. As such, the Central Bank should have a clear oversight role of international aid flows to ensure they contribute to the country’s foreign exchange reserves. The agreement must also confirm the government’s adherence to the highest standards of transparency on donor aid and stipulate oversight provisions.

Collection of Public Revenue

- Agreement on how to allocate natural resources revenues: The peace agreement must include provisions on whether the producing governorates will continue to get 20% of the proceeds from the sale of oil and gas, as is currently the case; whether the pre-war system that was in place will be re-implemented; or whether an entirely new arrangement will be put in place. In all cases, there must be a provision in the agreement that requires depositing oil and gas revenues into a special account at the Central Bank. The provision should also stipulate that an international auditor would monitor this account, and that the government would adhere to the highest standards of transparency in managing this vital sector.

- Depositing local revenue: The signatories of the agreement shall commit to a transparent and accountable process to ensure that the various local authorities collect all local revenue from taxes and customs fees into the government’s account at the Central Bank, after directly deducting the approved funds that have been allocated in the budget for local authorities.

- Appointments to revenue authorities during the transitional period: The agreement must specify transparent and merit-based criteria and mechanisms for appointing the heads of public revenue authorities and their branches throughout the country (i.e., tax authority, customs authority, etc.) and holding them accountable.

Reconstruction & Recovery

- Reconstruction and recovery: The peace agreement must include articles on reconstruction and recovery, including the governing principles for the reconstruction and recovery process as well as the institutional structures that will be tasked with managing this process. The aim of these articles is to ensure that the reconstruction and recovery efforts are efficient, transparent, and congruent with the interests of the Yemeni people. They must also cover the role of donors and the commitment to support the government in negotiating a mutual accountability framework with the donors for implementing/facilitating the reconstruction and economic recovery process with clear indicators.

Opening Seaports, Airports, & Land Border Crossings, & Lifting Restrictions

- Ending all restrictions in place: The peace agreement must enable the opening of the various seaports, airports, and land border crossings. It must also lift all restrictions that were imposed on the movement of goods and travellers, and terminate all programs that were put in place to search and inspect ships outside Yemeni ports. This could also be a confidence-building measure ahead of a peace agreement.

- Restoring basic security and confidence: Confidence of international maritime transporters in Yemen’s seaports, especially the Port of Aden and the Port of Hodeidah, must be restored through the provisions of the peace agreement. In addition, the peace agreement must establish the ground for regaining International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) compliance status at Yemen’s major terminals to restore trust amongst the international shipping community.[9]

Appendix: Yemen’s Chronic Macroeconomic Drivers of Instability

The historical and projected trends of all vital macroeconomic indicators for Yemen show an unprecedented gloomy economic outlook. Throughout the 2000s, Yemen’s economic policies did not succeed in stimulating economic growth; to the contrary, they mostly maintained a fiscal deficit, while a trade imbalance started growing quickly despite the notable growth of exports, and the national currency slowly but steadily lost its value against foreign currencies. During the decade that followed, these economic problems were magnified. Public finances collapsed as revenue dwindled, while public spending remained at high levels due to the war effort, bloated public sector’s wages, and fuel imports.[10] To finance the surge in the fiscal deficit, public debt increased sharply. Besides, due to the plunge in crude oil exports and suspension of LNG exports, Yemen became almost entirely a net importer of all goods.

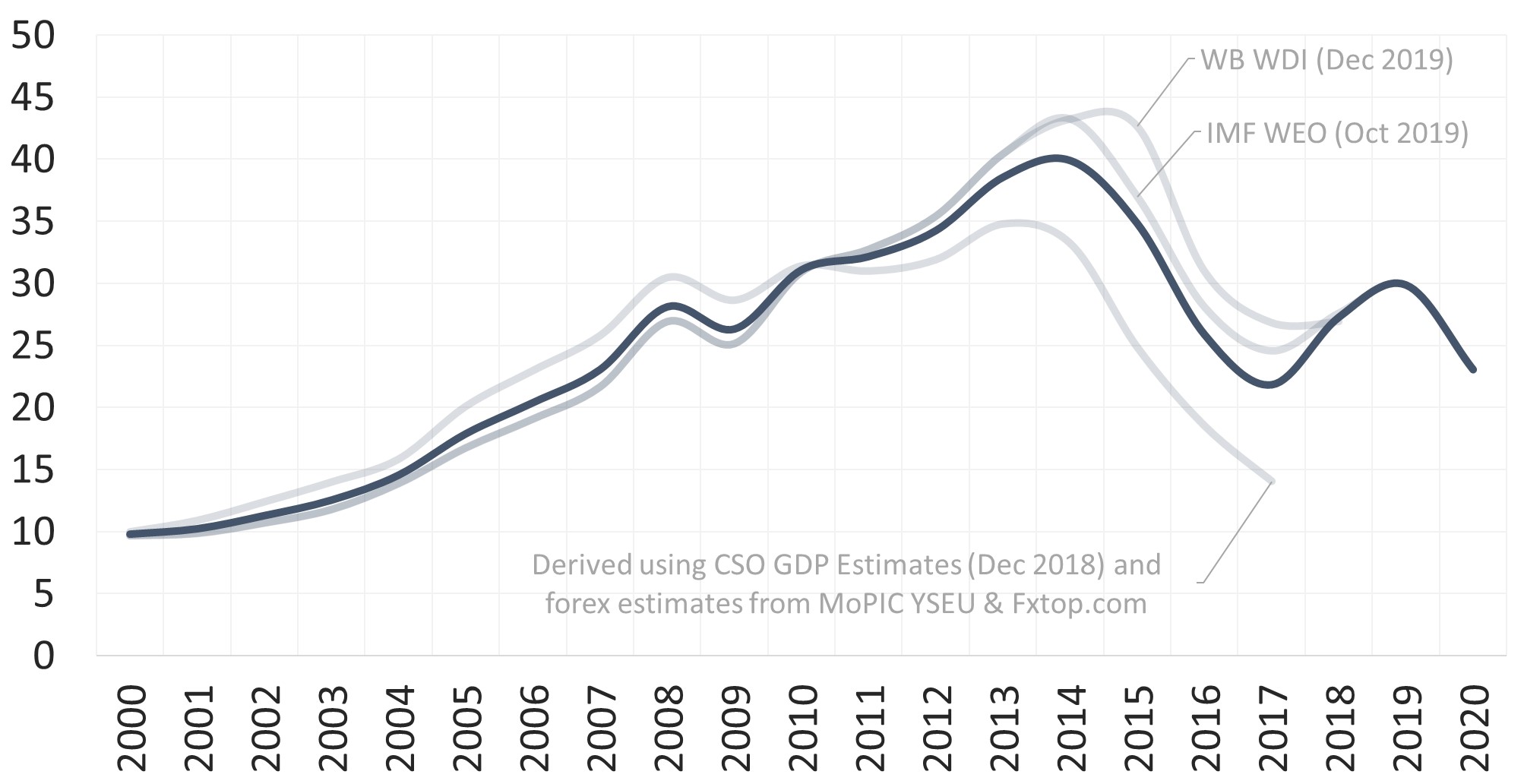

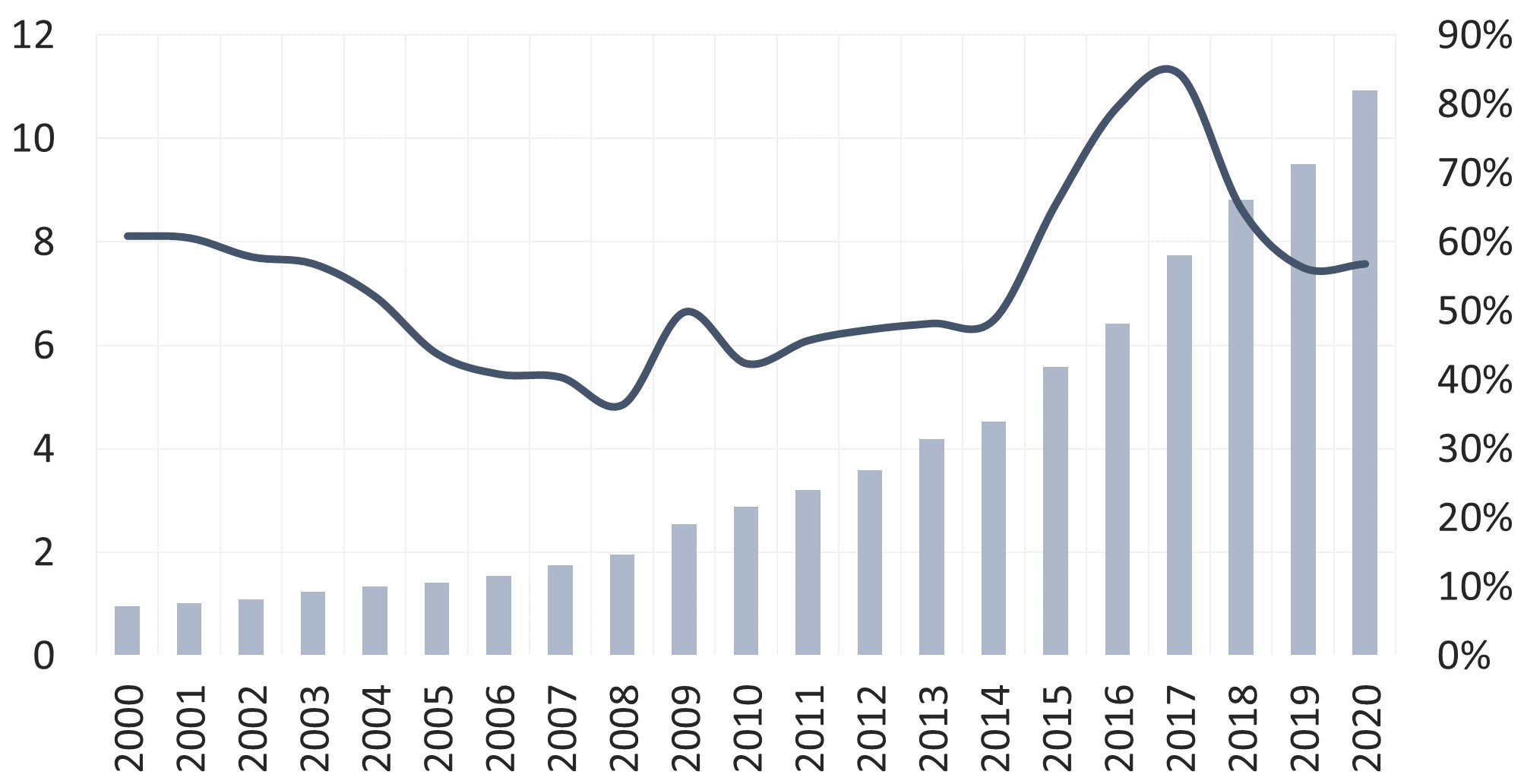

Compounded by rampant corruption that has always strained Yemen’s scarce resources, this poor management of Yemen’s economy and the subsequent wartime setbacks have altogether resulted in a significant contraction in Yemen’s economy. Just before the outbreak of the current COVID-19 pandemic, the IMF projected Yemen’s 2020 nominal gross domestic product (GDP) at $23 billion, a decline of 47% compared to over $43 billion in 2014.[11] Also, the exchange rate of the US dollar in the parallel market skyrocketed to a record high of 820 Yemeni rials per US dollar in October 2018, before stabilizing at the end of 2019 at around 600 rials per dollar. Meanwhile, double-digit inflation rates have continued to spiral out of control, exceeding their safe limits. According to one estimate, the inflation rates for 2017, 2018, and 2019 were 30.4%, 27.6%, and 14.7% respectively, climbing to 35.5% in 2020.[12]

The cost of economic recovery is insurmountable. Only one year into the war, the IMF estimated that Yemen lost 25-35% of its GDP in 2015 alone and over $20 billion—50% of pre-war GDP—in the country’s total infrastructure since the war’s onset.[13] At that time, it had already speculated that the costs of rebuilding the economy would by far exceed Yemen’s capacity to mobilize resources, especially given the limited scope for domestic revenue mobilization and high debt.[14]

Far beyond the costs of rebuilding the economy, the conflict’s devastating impact has reversed human development in Yemen. In a report published in April 2019, UNDP estimated that Yemen’s hard-earned human development gains had already been set back by 21 years.[15]

Any upcoming negotiations to end Yemen’s conflict will come against this backdrop of grave challenges. Surely, if neglected, these challenges will fuel discontent, instability, and insecurity in the immediate future just as they did in the past.

To summarize, the following specific economic challenges in Yemen have been identified by the Development Champions Forum as urgent and integral to any upcoming peace negotiations:

Restriction of economic activity

- Collapse of key state institutions and their division among the parties to the conflict

- Loss of the labour force due to displacement, death, injury, or joining the battlefield

- Hikes in unemployment and sweeping loss of income

- Inability of local traders to freely import and locally transport goods

- Prohibitive cost of conducting business in Yemen, local markets’ unattractiveness to investment and the inadequate business environment, and the subsequent capital flight

Collapse of public finances and their deepening structural deficiencies

- Unsustainable public spending and inability to pay salaries and wages

- Severe decline of public revenue and high public debt service burden

- Inability to cover necessary social protection

- Collapse of all essential public services

Collapse of the banking sector and the monetary system

- Division of the Central Bank of Yemen

- Conflicting monetary policies regarding a single currency and banking regulations

- Inability to control inflation

- Depletion of the Central Bank’s foreign currency reserves

- Depreciation of the local currency

- The severe liquidity crisis in the local banking system

- Lack of access to foreign currency in the local market to finance basic foodstuff imports

- Traders’ limited access to external financing and international banking services

|

Exhibit 1: Yemen’s Steady Population Growth versus Its Collapsed Economy |

|

|

(a) Population (Millions)

|

(b) Economic Growth (Real GDP Annual % Change)

|

|

Sources: (a) Average of available population estimates and projections from the following six sources: (1) Central Statistical Organization. “Projections for 2005-2025.” June 2010. (2) Central Statistical Organization. “Gross Domestic Product Estimates.” December 2018. (3) International Monetary Fund. “World Economic Outlook Database.” October 2019. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2019/02/weodata/index.aspx. (4) Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. “World Population Prospects 2019, Online Edition. Rev. 1.” August 2019. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/. (5) World Bank Group. “World Development Indicators.” https://data.worldbank.org/country/yemen%20rep. Accessed February 21, 2020. (6) Department of Statistics, International Labour Organization. “ILOSTAT Database – Population by sex and age – UN estimates and projections, July 2019 (thousands) – ILO modelled estimates.” https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/. Accessed February 21, 2020. (b) Average of available estimates and projections from the following four sources: (1) CSO GDP estimates, 2018 (Base = 2000). (2) United Nations. “Statistical Annex – Table A.3: Developing economies: rates of growth of real GDP, 2009-2019.” in “World Economic Situation and Prospects 2018.” 2018. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/WESP2018_Full_Web.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2020. (Base year unspecified). (3) IMF WEO, Oct. 2019 (Base = 1990). (4) WB WDI, Feb. 2020 (Base = 2010). The various estimates and projections are shown in light grey, which, despite their variance due to methodology, draw more or less the same trendlines. |

|

|

Exhibit 2: Macroeconomic Overview of Yemen During and Before the Conflict |

|

|

(a) Nominal GDP (Current Prices) (USD, Billions)

|

(b) General Gross Debt (YER, Trillions) & Its % of GDP

|

|

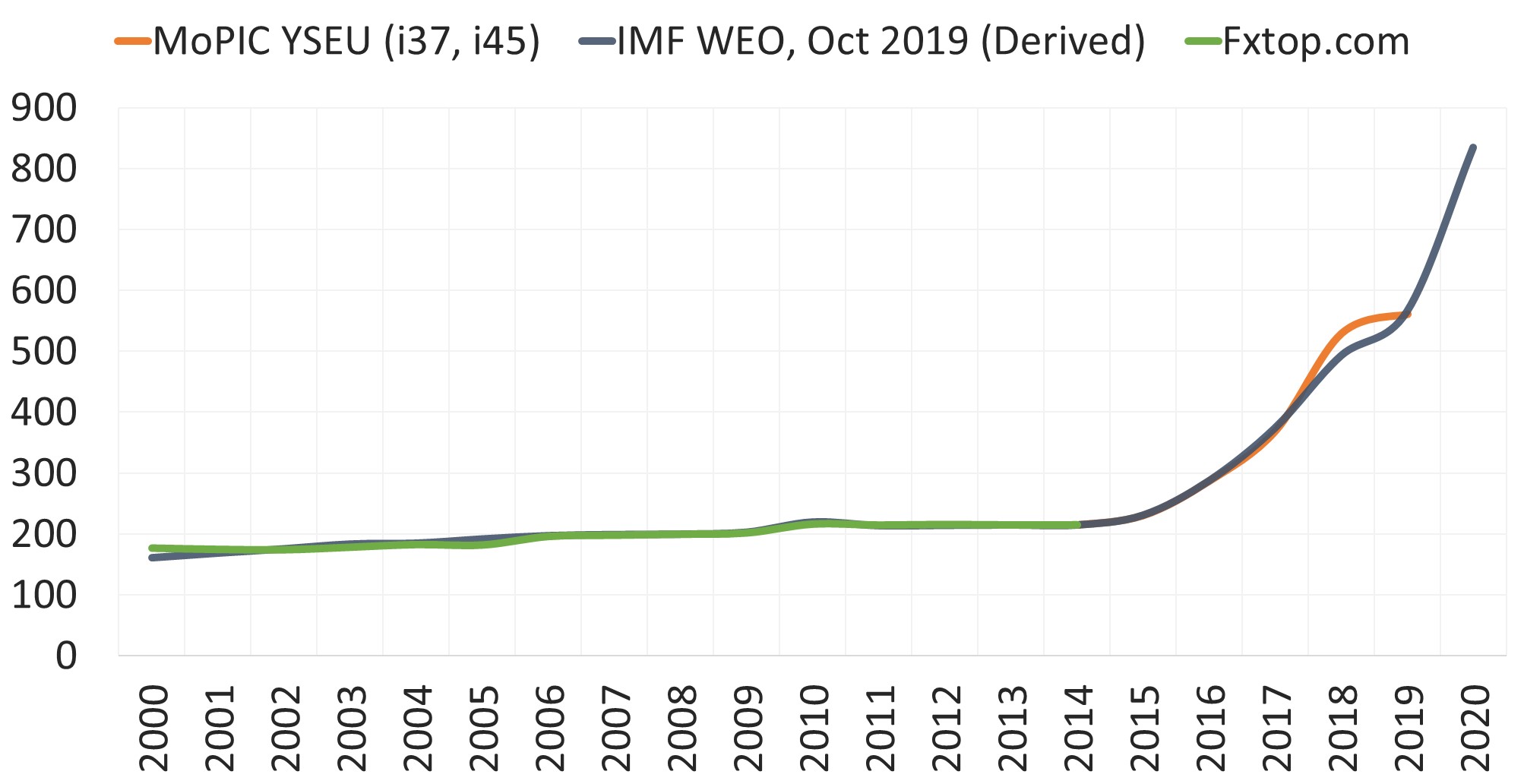

(e) USD/YER Forex in Parallel Market

|

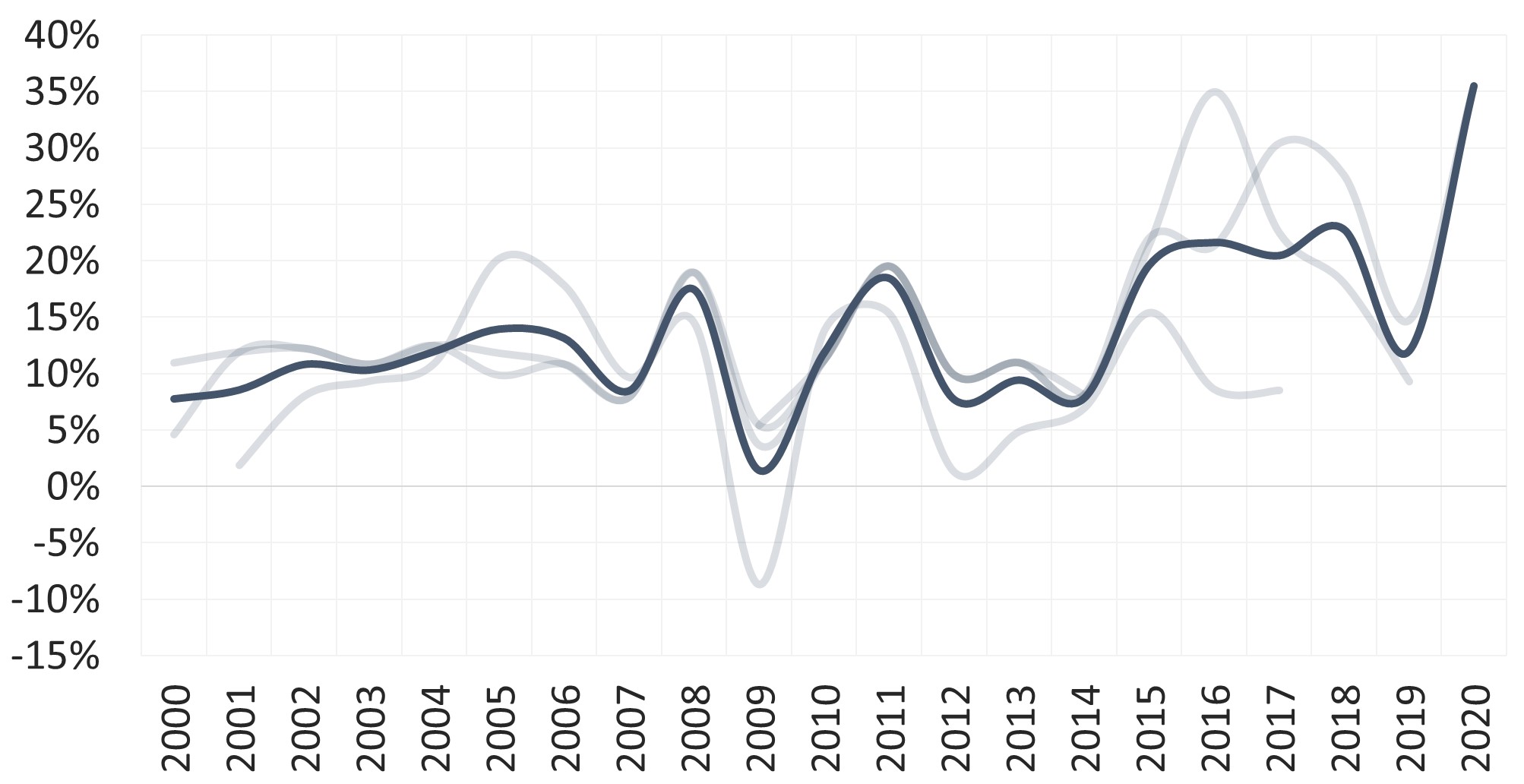

(f) Inflation (Consumer Prices Annual % Change)

|

|

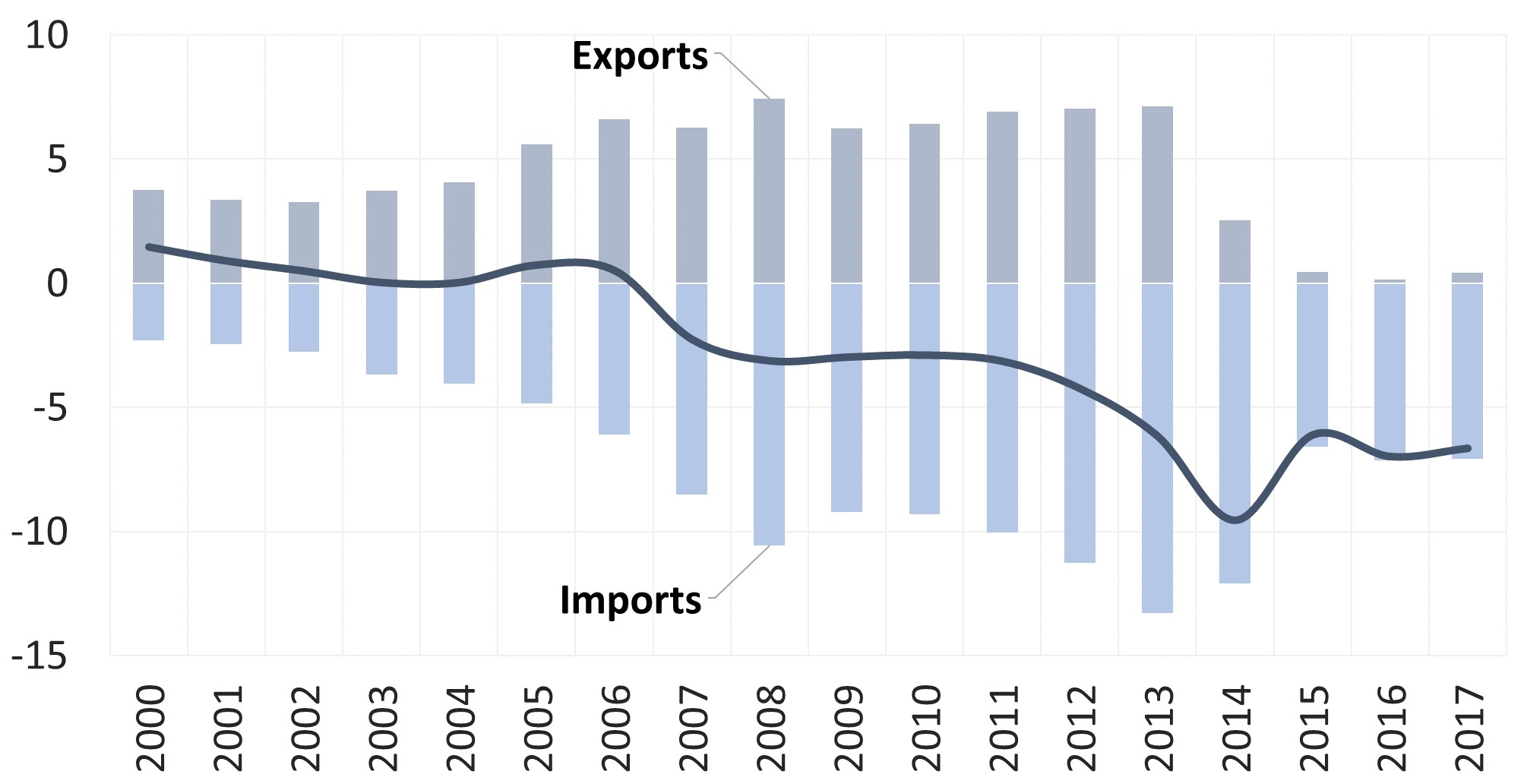

(c) Merchandise Trade Balance (USD, Billions)

|

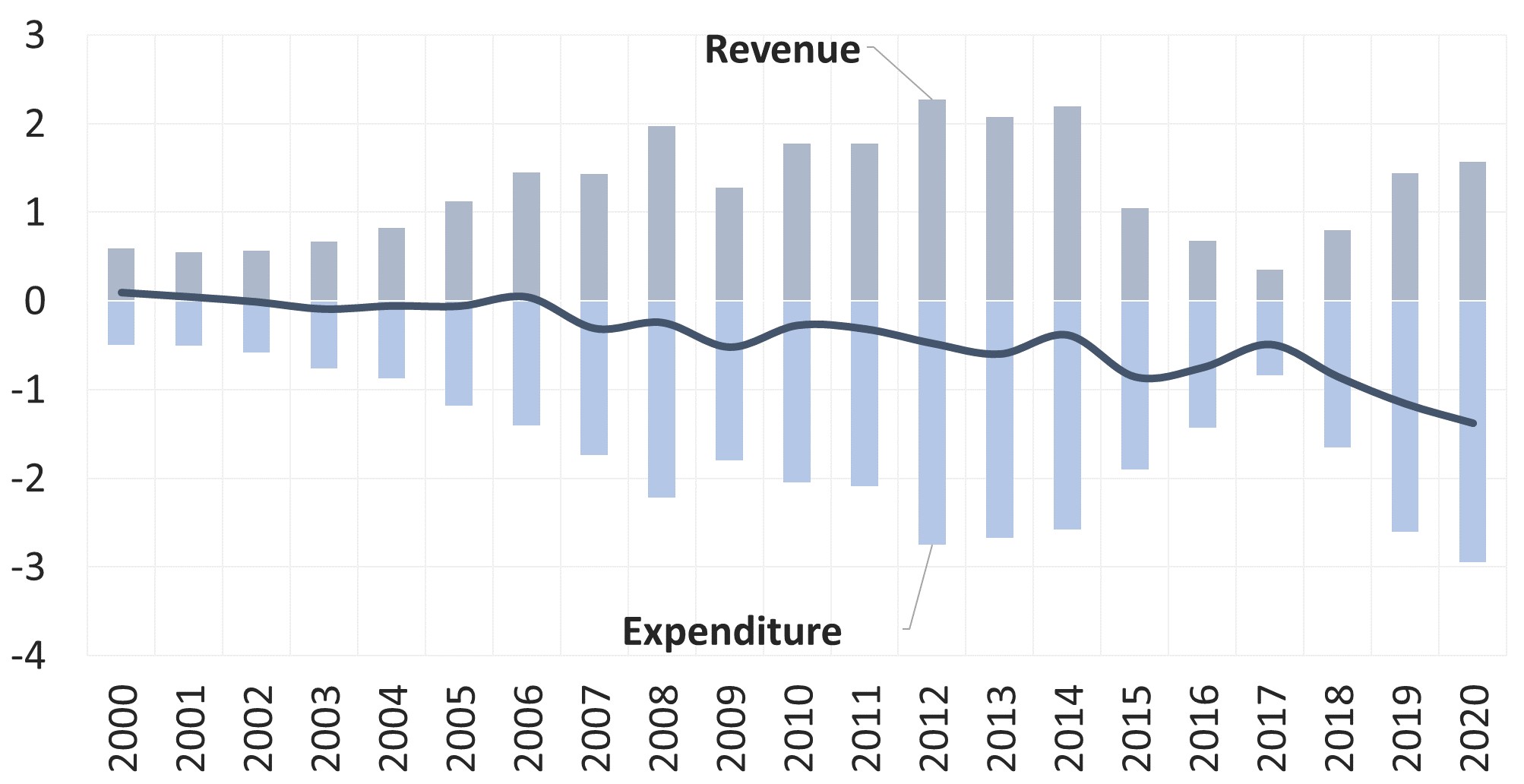

(d) Budget deficit (YER, Trillions)

|

|

Sources: (a) Average of available estimates and projections from the following three sources: (1) CSO GDP estimates, 2018. The local currency was converted to USD using historical annual average foreign exchange rates. For 2000-2013, the exchange rates were retrieved from https://fxtop.com/. For 2014-2017, the exchange rates were retrieved from issues 37 (“Riyal Devaluation Ignites Inflation”, September 2018) and 45 (“The Depreciation of the Yemeni Currency Aggravates the Suffering of Yemenis”, October 2019) of the “Yemen Socio-Economic Update” periodical issued by the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation. (2) IMF WEO, Oct. 2019. (3) WB WDI, Feb. 2020. The various estimates and projections are shown in light grey. It is noted that there is a large discrepancy post-2011 between the trendline charted using MoPIC data and IMF and World Bank data. (b, d) IMF WEO, Oct. 2019. (c) WB WDI, Feb. 2020. (e) Historical annual average foreign exchange rates were retrieved from the following three sources: (1) For 2000-2014, Fxtop.com. (2) For 2014-2019, MoPIC YSEU, issue 37 of Sep. 2018 & issue 45 of Oct. 2019. (3) For the entire period, derived from IMF WEO, Oct. 2019, by dividing nominal GDP in YER by the nominal GDP in USD. (f) Average of available estimates and projections form the following four sources: (1) CSO GDP estimates, 2018. (2) “Table A.6: Developing economies: consumer price inflation, 2009-2019” in UN WESP, 2018. (3) IMF WEO, Oct. 2019. (4) WB WDI. The various estimates and projections are shown in light grey, which, despite their variance due to methodology, draw more or less the same trendlines. |

|

footnotes:

[1] Al-Akhali, Rafat. “The Battle to Control the ‘Commanding Heights’ of the Yemeni Economy.” Middle East Centre, London School of Economics and Political Science. June 16, 2017. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mec/2017/06/16/the-battle-to-control-the-commanding-heights-of-the-yemeni-economy/. Accessed February 21, 2020.

[2] (i) BBC. “Yemen Profile – Timeline.” November 6, 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-14704951. Accessed February 21, 2020. (ii) Human Rights Watch. “In the Name of Unity: The Yemeni Government’s Brutal Response to Southern Movement Protests.” December 15, 2009. Accessed February 21, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/report/2009/12/15/name-unity/yemeni-governments-brutal-response-southern-movement-protests. (iii) The New York Times. “Worst riots in a decade leave 16 dead in Yemen.” July 22, 2005. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/07/22/world/africa/worst-riots-in-a-decade-leave-16-dead-in-yemen.html. Accessed February 21, 2020.

[3] Rethinking Yemen’s Economy (RYE). “Developing Human Capital.” January 16, 2020. https://devchampions.org/uploads/publications/files/Rethinking_Yemens_Economy-policy_brief_18.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2020.

[4] (i) Badanjak, Sanja. “Banks, central banks, and banking regulations in peace agreements.” (PA-X Report, Economic Series). Political Settlements Research Programme (PSRP), Global Justice Academy, University of Edinburgh. Edinburgh: 2019. http://www.politicalsettlements.org/publications-database/banks-banking-regulations/ or https://www.peaceagreements.org/publication/14. Accessed February 21, 2020. (ii) Bell, Christine. “Economic Power-sharing, Conflict Resolution and Development in Peace Negotiations and Agreements.” (PA-X Report, Economic Series). Political Settlements Research Programme (PSRP), Global Justice Academy, University of Edinburgh. Edinburgh: 2018. https://www.politicalsettlements.org/publications-database/economic-power-sharing-conflict-resolution-and-development-in-peace-negotiations-and-agreements/ or https://www.peaceagreements.org/publication/11. Accessed February 21, 2020.

[5] Woodward, Susan L. “Economic Priorities for Peace Implementation.” International Peace Institute (formerly the International Peace Academy). New York: October 2002. https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/economic_priorities.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2020.

[6] Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary General for Yemen. “Agreement on the City of Hodeidah and Ports of Hodeidah, Salif, and Ras Isa.” United Nations. New York: December 2018. https://osesgy.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/hodeidah_agreement_0.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2020.

It is worth noting that until the date of this publication, this provision of the Hodeidah agreement has not yet been implemented. While revenues have been deposited to an account at CBY Hodeidah Branch, no agreement was reached on the details of how to use it for payment of public salaries.

[7] Bell, 2018.

[8] Kadri, Ali. “World Bank ‘Economic Medicine’ and the Impoverishment of Yemen.” Global Research. 2012. https://www.globalresearch.ca/yemen-world-bank-economic-medicine-and-the-impoverishment-of-yemen/29167. Accessed February 21, 2020.

[9] ISPS is an international code that came into force in 2004. The code is part of the amendments made to the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) Convention (1974/1988) on minimum security arrangements for ships, ports, and government agencies, through the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and its member countries, to safeguard and protect ships and ports in the course of carrying out international trade. It prescribes responsibilities to governments, shipping companies, shipboard personnel, and port/facility personnel to “detect security threats and take preventative measures against security incidents affecting ships or port facilities used in international trade.”

[10] In October 2019, the IMF projected Yemen’s general government expenditure for 2020 at almost three trillion Yemeni rials (YR 2.95 trillion) with the following fiscal assumptions: “Hydrocarbon revenue projection are based at WEO assumptions for oil and gas prices (authorities use $55/brl) and authorities projections of production of oil and gas. Non-hydrocarbon revenues largely reflect authorities projection, as well as most of the expenditure categories with exception of fuel subsidies which are projected based at WEO price consistent with revenues. Monetary projection are based on key macroeconomic assumptions on growth rate of broad money, credit to private sector, deposit growth. Start/end months of reporting year: January/December GFS Manual used: Government Finance Statistics Manual (GFSM) 2001 Basis of recording: Cash General government includes: Central Government; Local Government; Valuation of public debt: Nominal value Primary domestic currency: Yemeni rial Data last updated: 08/2019.”

[11] IMF WEO, Oct. 2019.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Lagarde, Christine. “The Calculus of Conflict in the Middle East.” International Monetary Fund. September 16, 2016. https://blog-imfdirect.imf.org/2016/09/16/the-calculus-of-conflict-in-the-middle-east/. Accessed February 21, 2020.

[14] Rother, Björn et al. “The Economic Impact of Conflicts and the Refugee Crisis in the Middle East and North Africa.” Staff Discussion Notes No. 16/8, International Monetary Fund. September 16, 2016. (ISBN/ISSN: 9781475535785). http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=44228.0, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2016/sdn1608.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2020.

The authors pointed out that the still ongoing large-scale conflicts in the Middle East leave deep marks on economies. For example, they estimated at the time of their report that “even with a relatively high annual growth rate of 4.5 percent, it would take Syria more than 20 years just to rebound to its 2010 pre-conflict GDP level.”

[15] United Nations Development Program (UNDP), in cooperation with the Frederick S. Pardee Centre for International Futures and the Josef Korbel School of International Studies in the University of Denver. “Assessing the impact of war on development in Yemen.” April 23, 2019. https://www.arabstates.undp.org/content/rbas/en/home/presscenter/pressreleases/2019/yemen-has-already-lost-2-decades-of-human-development.html. Accessed February 21, 2020.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية