Executive Summary:

Executive Summary:

This policy brief summarizes discussions regarding Yemen’s human capital at a “Rethinking Yemen’s Economy” workshop held in Amman, Jordan, on August 24-25, 2019. The workshop participants agreed that Yemen’s human capital accumulation has almost certainly regressed since the current conflict began. However, there is a dearth of reliable data to assess the scope and nature of this regression and thus how to best direct responses. There was also a consensus that many of the obstacles to improving Yemen’s human capital were present prior to the current conflict. In line with these findings, this brief recommends: countrywide population surveys; more funding of development projects over emergency humanitarian assistance; education reforms; and the targeting of sectors with high human capital returns. Crucially, policymakers should not wait for the end of the conflict to implement these recommendations. Investment in Yemen’s human capital now, specifically in geographic areas away from frontline fighting, should hasten the speed of the post-conflict economic recovery and lay the foundations for the sustainable development of the economy beyond the war.

Introduction

As part of the “Rethinking Yemen’s Economy” initiative, a group of education and healthcare specialists, private sector actors, and civil servants, including representatives of the Development Champions, convened in Amman, Jordan, on August 24-25, 2019, for a workshop on Yemen’s human capital. This policy brief presents some of Yemen’s human capital indicators before and during the current conflict, while highlighting some of the obstacles to gathering required statistical data. It also presents recommendations to strengthen human capital in Yemen at the macro-level.

Participants assessed the current conflict’s impact on Yemen’s already weak human capital ratings – as illustrated by alarming health, education and employment indicators – to be at the heart of what the United Nations has called the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

While workshop participants agreed that the current conflict has likely precipitated a regression in Yemen’s human capital accumulation, much of this decline can be attributed to a magnification of pre-existing problems. For decades, rather than investing in human capital, the Yemeni government pursued a narrow economic vision based on Yemen’s depleting oil reserves. Acknowledgment of the historically entrenched, structural constraints that have hindered human capital development in Yemen fed into discussions on how best to reverse this trend in the short, medium and long term. Participants sought to identify opportunities to instigate change in spite of the ongoing conflict, with the ideal (but not easily achievable) goal of identifying measures that would not only provide immediate relief but also endure beyond the conflict.

Amid weakened state governance in Yemen since the outbreak of the current conflict, there is scope for greater private sector investment in human capital. The state still has a lead role to play in terms of oversight and policy formation, but the private sector is in a stronger, more flexible position to assist with the implementation of certain policies designed to strengthen Yemen’s human capital development. Participants stressed the need for greater coordination between the public and private sectors concerning Yemen’s education system and the provision of knowledge and skills that will better prepare Yemenis for the domestic and foreign job markets. Participants added that donors could also provide financial and technical assistance by placing greater emphasis on development aid, as opposed to focusing primarily on emergency humanitarian relief. Investing in Yemen’s human capital now, specifically in those areas of the country that are not experiencing frontline fighting, rather than waiting for the overarching conflict to end, should hasten Yemen’s post-conflict economic recovery.

Participants also highlighted the importance of targeting sectors with room for growth through the more effective use of Yemen’s human resources; harnessed in the right way, Yemen’s young, rapidly growing population offers sizeable socioeconomic gains. Agri-business, service, and mining were singled out as sectors that could benefit from this human resource boom.

Definition of Human Capital

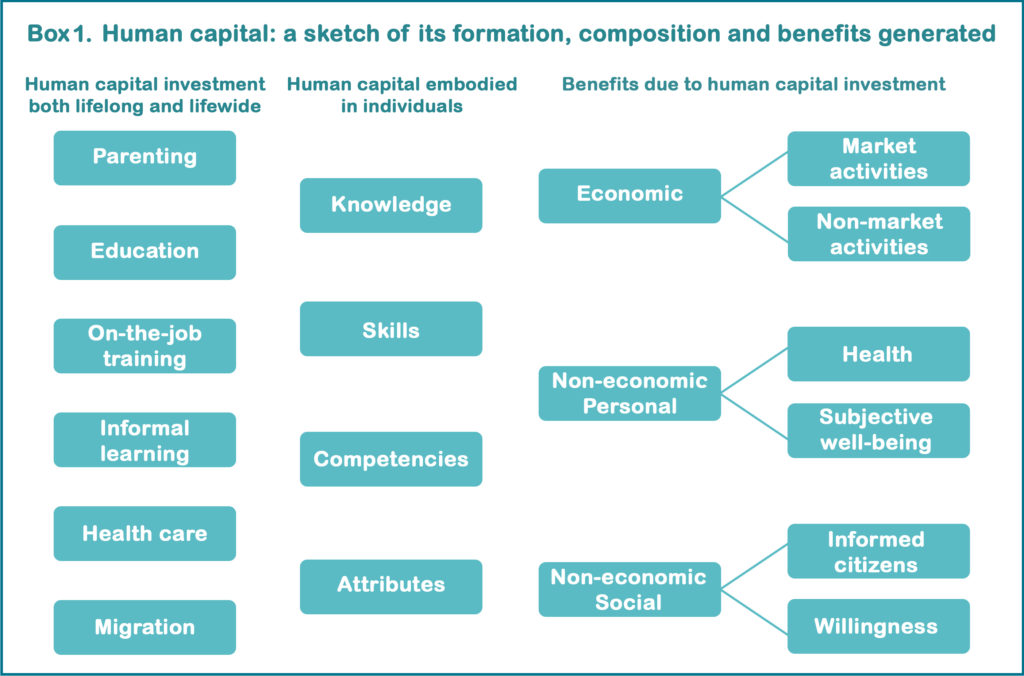

The World Bank defines human capital as “the knowledge, skills, and health that people accumulate throughout their lives, enabling them to realize their potential as productive members of society.”[1] The following diagram (Figure 1. Human Capital), charts the different sources of human capital and how this human capital investment translates to individual and societal benefits. The advancement of individual human capital is widely regarded as a key component of socioeconomic productivity and development.[2] Lastly, the public and private sectors are both accepted as playing a role in harnessing human capital accumulation.[3]

Figure 1. Human Capital  Source: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Conference of European Statisticians, 2016

Source: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Conference of European Statisticians, 2016

Human Capital in Yemen Before the Conflict

In Yemen, human capital accumulation has been stunted by cyclical violence and instability, and a lack of investment by the government, among other factors. Health and nutrition indicators imply that human capital in Yemen was already very weak before the onset and escalation of the current conflict. For example, in 2009, 31.5% of the total population – about seven million people – were food insecure, urging the World Food Programme in its 2009 Comprehensive Food Security Survey to call for “urgent, bold, and immediate interventions to avoid the situation from worsening.” By 2011, 44.5% of the total population – about eleven million people – were food-insecure, a deterioration in the national number of food-insecure population of almost 60% compared to 2009.[4] In fact, according to the Global Hunger Index (GHI), Yemen rankings of the severity of hunger of its population have been falling under the “alarming” category since 1992.

Education and employment indicators draw the same dreary image about the overall state of human capital – the latter of which is covered extensively in the Yemen Labor Force Survey 2013-2014 conducted by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor and the Central Statistical Organization (CSO), with support from the International Labour Organization.[5] To note but a couple of examples from the Yemen Labor Force Survey, before the current conflict the majority of Yemen’s male-dominated 4.86 million-strong workforce were uneducated and informally employed.[6] Only 23 percent of the workforce had received secondary education and only 8 percent had received post-secondary education.[7] Workshop participants noted how the nature of schooling and education in Yemen had underprepared students to enter the job market and had acted as a brake on Yemen’s human capital accumulation. The experts present during the discussions in Amman pointed toward an emphasis on rote learning (memorization techniques) over critical thinking and an outdated curriculum that did not offer enough vocational training nor adequately prepared students for the job market. Rapid population growth in Yemen in an environment of limited foreign direct investment and poor economic growth led to insufficient employment opportunities for young people, and in turn rising unemployment and poverty rates.

A young and fast-growing population such as Yemen’s could be used as a vehicle through which to stimulate economic growth if the conditions are right and job-seekers are presented with a range of career paths that promote progression based on meritocracy. In Yemen, however, the growing youth population has been faced with a weak job market plagued by a lack of economic opportunities and diversification as well as nepotism and corruption. This lack of job opportunities for the younger generation has in turn fueled discontent, instability, and insecurity, giving rise to a number of socioeconomic problems such as child marriage and the recruitment of young men into armed groups. These problems have become more pronounced during the current conflict.

The Current Conflict and Yemen’s Human Capital Regression

The war in Yemen has left a path of destruction in its wake – the effects of which extend well beyond the frontlines and will be felt for years after the conflict ends. It is impossible to quantify the impact on Yemen’s already underdeveloped human capital, but some of the health, education, and employment indicators paint a bleak picture. The country’s human capital growth has likely been set back years if not decades; hence the importance of trying to counter this reality sooner rather than later.

An estimated 24 million Yemenis – 80 percent of the population – require some form of humanitarian assistance to survive.[8] Yemen’s economic decline has arguably had a larger impact on the broader population than the violence itself, and is one of the major driving forces behind Yemen’s deepening humanitarian crisis.[9] Rising unemployment and poverty levels have been exacerbated by the devaluation of the Yemeni rial and a subsequent drop in purchasing power. The cumulative impact has left many Yemeni households struggling to put food on the table or access medicine or healthcare when required.

Life-threatening diseases such as cholera have also taken root. The outbreak is proving difficult to counter in light of the decimation of basic services such as garbage collection, waste management, water treatment and supply, access to fuel and the provision of electricity.[10] That is not to mention the debilitation of Yemen’s healthcare system: almost half of Yemen’s public healthcare facilities have ceased operating during the conflict, while the majority of those that remain open are suffering from medical and staff shortages that leave them only partially operational.[11]

As for Yemen’s education system, UNICEF reported on September 25, 2019, that one in five education facilities that were operational before March 2015 are now closed. According to this report, there are currently 2 million Yemeni children out of school — almost 500,000 of whom dropped out shortly after March 2015.[12] As school dropout rates have increased, so too have the number of child marriages and child soldiers.

These alarming indicators go some way to illustrating the impact of the conflict on Yemen’s human capital. Statistics never tell the full story, however; particularly during times of war, when accurate, widespread data collection and verification are nearly impossible. The Yemeni governmental body, the Central Statistical Organization (CSO), last carried out a national census in 2004. Since then, data that has been collected by UN agencies, international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) is often limited in geographical scope and sample size. The general assumption is that the humanitarian and development picture in Yemen is much bleaker than has been reported.

Given the severity of Yemen’s humanitarian crisis, the emphasis placed on the provision of emergency relief by UN agencies, INGOs, humanitarian organizations and their respective donors is understandable. The consensus among workshop participants was, however, that the international community is too narrowly focused on emergency humanitarian relief and that more development aid ought to be provided to Yemen. Participants insisted that Yemen does not want to be a “nation of beggars” where food baskets are seen as the easy solution, but are ultimately millions of dollars of aid literally “eaten up” – while also distorting the local market and impacting the existing private sector – without lasting benefit for society. They argued instead for more careful examinations of where development assistance can be provided at the local level with a view to offering sustainable solutions that Yemen can benefit from beyond the current conflict.

Recommendations

Short Term:

Capitalize on Yemen’s Upcoming Demographic Window

To change the unsustainable crisis-response narrative about Yemen, the government should formulate a desperately-needed human capital vision, strategy, and national as well as sectoral policies for the next 10 years, especially in vital economic sectors of Yemen that can precipitate human capital growth. This vision ought to capitalize on a precious human capital opportunity for Yemenis, which is the forgotten upcoming demographic window. By our estimates, Yemen is expected to enter the demographic window of opportunity around 2030 as a result of a shift in the population’s age structure, whereby the working-age population – assumed to be, in the case of Yemen, from the ages of 16 to 59 – will be larger than the non-working-age population.

Based on our analysis[13], Yemen’s working-age populations will continue its slow and steady increase and shall account for approximately half of the population by 2050. The growing working-age population promises either a “demographic bonus” or yet another era of unrest in Yemen – if it does not obtain quality education and cannot find good employment and fair opportunities for economic prosperity. In 2015, it was estimated that 7.5 million males fell in the working-age group, a number that is projected to double by 2050, exceeding 15 million. Religious extremism and fanaticism, civil wars, and the Qat dilemma – to name only a few of Yemen’s long-standing list of specifically man-made problems – will surely persist, unless effective policy measures and government interventions prevent that.

Enable the Central Statistical Organization (CSO) to Conduct Field Surveys

Were the main warring parties to grant the CSO greater room to maneuver free of political interference, the body would be in a much stronger position to properly assess the impact of the conflict. This information could then be shared with UN agencies, INGOs, humanitarian organizations and donors to deepen their understanding and to assist policy and decision-making as well as humanitarian aid programming and implementation. The information could also guide efforts to safeguard and invest in Yemen’s human capital in spite of the ongoing conflict.

The warring parties should set the terms and conditions for a mutually agreed framework that enables the CSO to conduct an extensive field survey that spans as much of Yemen’s territory as possible. The field survey should chart a number of population indicators that would help deepen the current level of understanding of the conflict’s impact on Yemen’s human capital. The survey should aim to assess: (a) local population indicators that subsequently account for any population movement and displacement during the conflict; (b) health and education indicators such as the number of health and education facilities that are still operational and an assessment of the population’s level of access to both; and (c) employment indicators for the public and private sectors.

The main warring parties should agree on the scope, methodology and operational budget to enable the CSO to carry out the field survey. In order to establish a mutually agreed framework that the CSO can then implement, a consensus will likely need to be reached on the following:

- Identifying specific areas of engagement that the CSO can operate in, in addition to the listing of specific areas that the CSO is not authorized to operate in;

- Determining the sample size based on the budget allocated for the field survey;

- Determining the sample within each governorate in proportion to its estimated population size, taking into account that the numbers from 2004 may not be correct for some governorates[14]; and

- Ensuring the differences between urban and rural areas are accounted for. While the majority of Yemen’s population resides in rural areas, there are indicators that suggest an ongoing shift. This appears to be due to a number of factors related to the conflict, such as displacement and the search for employment – both of which have contributed to rapid population growth in Marib governorate, for example.

International Donors Should Invest More in Development

There is now an increased focus from international donors on funding projects that promote socioeconomic development in Yemen. More can be done, however, and international donors should consult with public and private sector actors in Yemen in order to assess the viability of introducing an increased number of development projects at the local level.

International donors are understandably concerned about the need to continue providing emergency humanitarian relief to mitigate the negative impact of Yemen’s humanitarian crisis. Wherever possible, however, international donors should look to combine emergency humanitarian relief efforts with development aid, empowering local actors and fostering benefits from this assistance beyond the current conflict. Moreover, combining humanitarian relief with investment in human capital through the provision of school meals nation-wide should be considered.

International donors should carry out a thorough assessment to determine which specific geographic areas to target and what kinds of technical and financial support to offer. This assessment should go beyond common or narrow themes that quantify the obvious sufferings of Yemenis as opposed to trying to provide an innovative and far-sighted human development framework that goes beyond the ongoing conflict. It must focus more on long-run human development growth through policy measures that promote, for example, knowledge, innovation, and entrepreneurship, in addition to ensuring the provision of critical health and education services.

Donors should also look to coordinate efforts with local institutions, such as the CSO (if it is granted greater freedom to maneuver by the warring parties, as per the above recommendation) and the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, as well as other public and private sector actors. For example, instead of making regular deliveries of clean drinking water to areas that are currently struggling to obtain this essential commodity, international donors could look to work with local private sector actors (e.g. construction companies) to build a water treatment and bottling facility. The project could look to employ members of the local population in the construction work, and train other members of the local population to work at the facility once constructed. Emergency assistance can continue while the facility is being built.

Medium to Long Term:

Educational Reforms

Looking beyond the current conflict, national and local governing authorities – specifically the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Technical Education and Vocational Training – should carry out education reforms in coordination with private sector actors. Formal partnerships between education institutions and private sector actors is one avenue that could be explored, while also including representation of select civil society organizations (CSOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

A central component of any education reform strategy in Yemen should be improving the link between Yemen’s education system and the country’s job market. Gender must also be taken into consideration to ensure that women are granted access to education and better represented in the public and private sector workforces.

Any education reform attempts must also consider the skills needed for different sectors, the public and private sector actors involved and their respective responsibilities (e.g. provision of technical training). By making high-school, college, and university education and vocational training sector-oriented, Yemeni citizens should find themselves better prepared to enter certain sectors in the domestic and foreign job markets.

Invest in Sectors With High Returns

Specific sectors can be targeted in view of enhancing human capital, social development, and economic growth, as well as in terms of harnessing the potential of productive industries and generating new employment opportunities. (See RYE policy brief ‘Generating New Employment Opportunities’ published in October 2018.[15]) Workshop participants said that the fishing and agricultural should be prioritized, given that the majority of Yemen’s working-age population reside in rural areas and of those the majority are employed in these sectors. They also agreed that services, as well as mining and minerals sectors should be given more attention. All of these sectors have huge, relatively untapped potential. Participants

Participants also said that consideration should be given to promoting employment of Yemenis in neighboring countries’ service sector (e.g. call centers). the Yemeni economy will likely not be capable of absorbing the entire Yemeni workforce. Therefore, exporting Yemeni workforce – and training people for certain sectors abroad – should be part of an overall human capital strategy for the future.

Endnotes

[1] World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/human-capital/brief/about-hcp, accessed October 12, 2019 .

[2] World Bank Group, “The Human Capital Project,” (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018), https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/30498/33252.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y, accessed October 12, 2019.

[3] Pietro Calice, “How Financial Deepening Can Contribute to Human Capital Development,” Private Sector Development Blog, World Bank Group, April 30, 2019, https://blogs.worldbank.org/psd/how-financial-deepening-can-contribute-human-capital-development, accessed October 12, 2019.

[4] World Food Programme (WFP), “Comprehensive Food Security Survey 2012: The State of Food Security and Nutrition in Yemen.” 2012. Accessed January 9, 2019. http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/ena/wfp247832.pdf?_ga=1.262912651.687705134.1486911247.

[5] International Labour Organization (ILO), “Yemen Labour Force Survey 2013-14,” (Beirut: International Labour Organization, 2015), 7, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—-arabstates/—-ro-beirut/documents/publication/wcms_419016.pdf, accessed October 12, 2019; World Bank, “The Republic of Yemen: Unlocking the Potential for Economic Growth,” Report No. 102151-YE (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2016), xi, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/23660/Yemen00Republi00for0economic0growth.pdf; “Generating New Employment Opportunities in Yemen,” Rethinking Yemen’s Economy, October 17, 2018, https://www.devchampions.org/publications/policy-brief/Generating-new-employment-opportunities, accessed October 16, 2019.

[6] ILO, Yemen Labour, 7.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “About OCHA Yemen,” OCHA, https://www.unocha.org/yemen/about-ocha-yemen, accessed October 16, 2019.

[9] “Generating New Employment Opportunities in Yemen”, Rethinking Yemen’s Economy, October 17, 2018, https://devchampions.org/publications/policy-brief/Generating-new-employment-opportunities. Accessed November 15, 2019.

[10] “CHOLERA SITUATION IN YEMEN”, World Health Organization, November 2018, applications.emro.who.int/docs/EMROPub_2018_EN_20770.pdf?ua=1. Accessed November 15, 2019.

[11] ” WHO enhances access to basic health care in Yemen”, World Health Organization, December 17, 2018, www.emro.who.int/yem/yemen-news/who-enhances-access-to-basic-health-care-in-yemen.html. Accessed November 15, 2019.

[12] “As school year starts in Yemen, 2 million children are out of school and another 3.7 million are at risk of dropping out,” UNICEF, September, 25, 2019. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/school-year-starts-yemen-2-million-children-are-out-school-and-another-37-million, accessed October 16, 2019.

[13] This analysis is based on the United Nations’ official population estimates and projections (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), Population Division, “World Population Prospects,” http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/DVD/. Accessed January 9, 2020.

[14] For example, the census data for al-Mahra from the 2004 survey is estimated to be significantly lower than the actual population size.

[15] “Generating New Employment Opportunities in Yemen,” Rethinking Yemen’s Economy.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية