The story is familiar. Dina,[1] an eight-year-old girl, lost both her legs after stepping on a landmine designed to detonate under a weight exceeding eight kilograms. She had been eagerly awaiting her return to her home, situated close to a frontline between government and Houthi forces in Al-Durayhimi district, Hudaydah. Her father had assured her they would return home and that the fighting would cease following the Stockholm Agreement in December 2018. However, her home and its garden had been transformed into a deadly playground, littered with anti-personnel landmines cunningly disguised as innocuous objects — rocks, household items, and even toys.

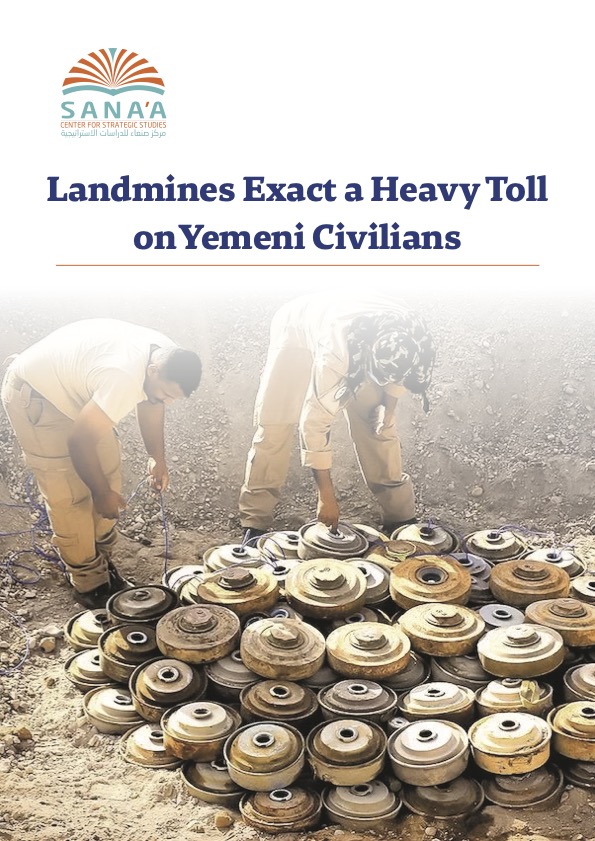

Civilians in Yemen, including women and children, have been displaced from their homes and farms, only to find themselves in areas contaminated by mines and unexploded ordnance. Lacking any knowledge of the tactics used by parties to the conflict, they are vulnerable to these deadly hazards, which are often indiscriminately planted during military withdrawals. The internationally recognized government alleges that the Houthis have planted two and a half million landmines in areas affected by the conflict since March 2015. Compounding the crisis is the ongoing refusal of the warring parties to provide maps of these minefields to specialized agencies, as required by the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention (APMBC), which Yemen signed in 1998.

Despite entering its third year, the truce in Yemen and subsequent dearth of major offensives has failed to halt the deadly toll of landmines and unexploded ordnance. These insidious devices, often referred to as “silent killers,” lie in wait. A single misstep can prove fatal for the victim. Yemen now ranks third globally in terms of landmine and cluster munition victims, with over 9,500 civilians, mostly women and children, killed or injured since March 2015, according to the Yemen Executive Mine Action Center (YEMAC) in Sana’a.

Yemen’s landmine crisis dates back to the 1980s, when 12 million mines were transferred from Libya to Yemen. Many were planted in the border region between North Yemen and South Yemen. In 2007, a Yemeni lawyer filed a lawsuit against the then-leader of Libya, Muammar Gaddafi, demanding compensation for the damage and injuries caused to Yemeni civilians. The legacy of this chapter of Yemen’s history continues to plague countless civilians today, particularly farmers and herders who fall victim to mines that litter farms and pastoral areas. Witness accounts gathered by Human Rights Watch, along with evidence collected by local human rights organizations, indicate that Republican Guard forces planted anti-personnel landmines around their camps in Bani Jarmuz area near Sana’a in 2011. In August 2023, sources within the 2nd Military Region in Hadramawt reported that an engineering team had dismantled a network of landmines and explosive devices planted by Al-Qaeda.

The majority of landmine victims are civilians. Women and children are vulnerable as they engage in activities such as collecting firewood and water and tending to livestock and may lack the experience to identify or avoid mines. Children are particularly vulnerable because they are often out playing. Ibrahim, a boy from Al-Jawf, was only eight when a mine claimed his life. The object resembled a pen – conflict parties often disguise these deadly weapons as everyday items.

In 2018, as a result of the war and the division of government institutions and bodies between the north and south, the Yemen Executive Mine Action Center (YEMAC) in Aden was formed as an independent entity from the main center in Sana’a, which was established in December 1999. The Center had heavily relied on a specialized unit of mine-detection dogs, but they were tragically bombed by the Saudi-led coalition in October 2021, further exacerbating the challenges of identifying and clearing war remnants and mined areas.

The clearance of land, farms, and roads from mines and explosive remnants of war not only safeguards civilians from direct injury but also facilitates the free movement of goods and people, enabling access to essential services, employment, education, and other aspects of life.

However, despite multiple rounds of peace talks, both regionally and internationally brokered, the warring parties in Yemen have refused to provide clear maps of minefields. Instead, they wield these life-saving resources as bargaining chips to advance their respective agendas. Given that landmines can remain active for decades, there continue to be regular reports of civilian casualties, including fatalities, survivors left with “permanent disabilities,” and victims of psychological trauma, as well as social and economic losses.

An employee with the Yemen Association for Landmines and UXO Survivors in Sana’a said that the NGO has recorded nearly nine thousand survivors of incidents involving landmines or unexploded ordinance. The care provided to them is limited to post-injury medical attention, physical rehabilitation, and locally made prosthetics, wheelchairs, and crutches. The number of victims represents just those recorded by the main office in Sana’a, and these survivors have no representation in the ongoing peace negotiations to advocate for their rights and needs. Any settlement that does not include compensation and rights for these victims risks leaving them in the lurch.

Mine survivors, many of whom have suffered limb amputations, require comprehensive and sustainable care. This care should be provided right after the occurrence of the incident and should continue until survivors can resume their lives as fully as possible. Such an endeavor necessitates a well-coordinated system and sustained efforts and support to heal the wounds of these victims and empower them to seek appropriate compensation.

This commentary was produced as part of the Yemen Peace Forum, a Sana’a Center initiative that seeks to empower the next generation of Yemeni youth and civil society activists to engage in critical national issues.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية