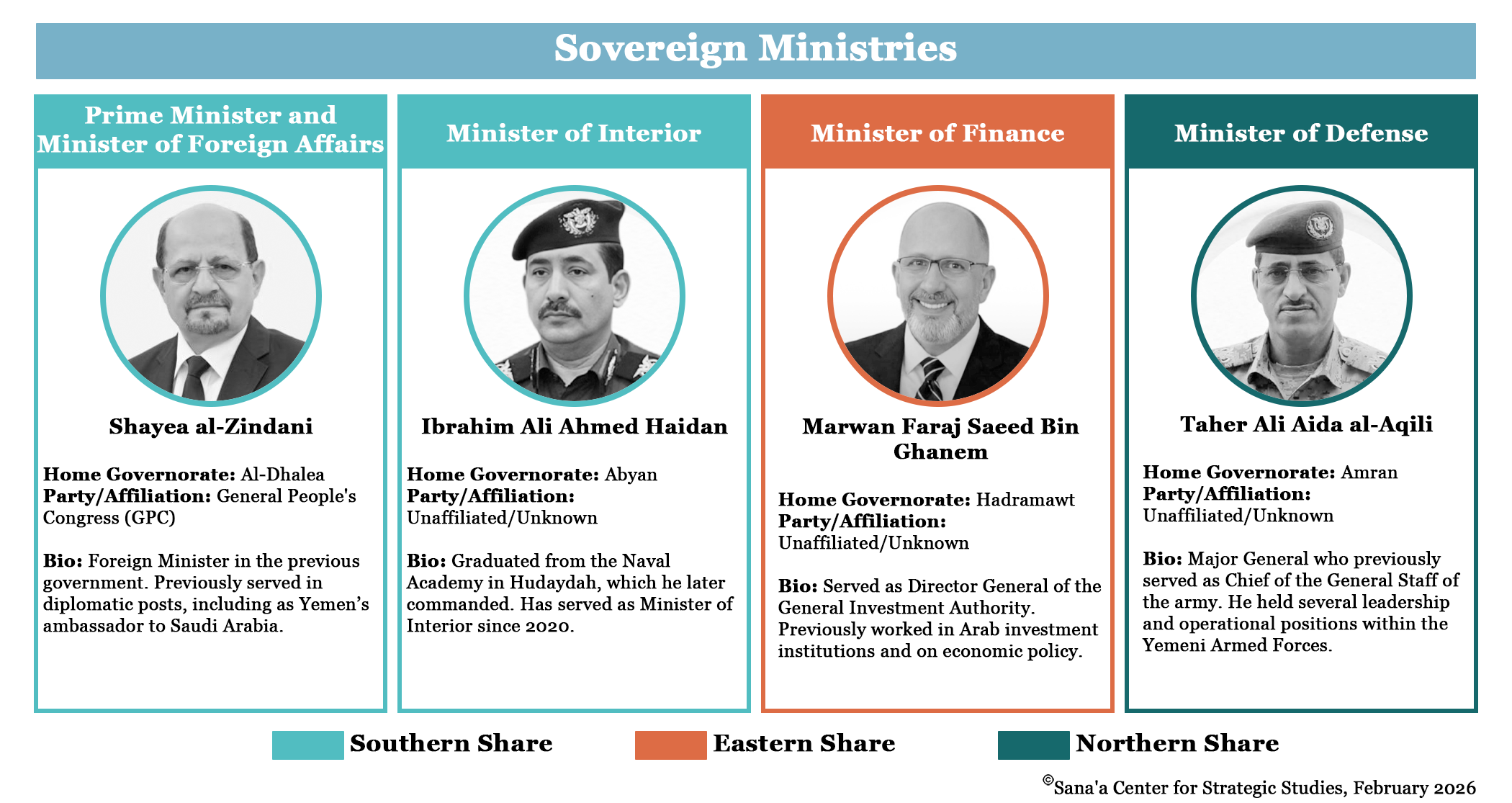

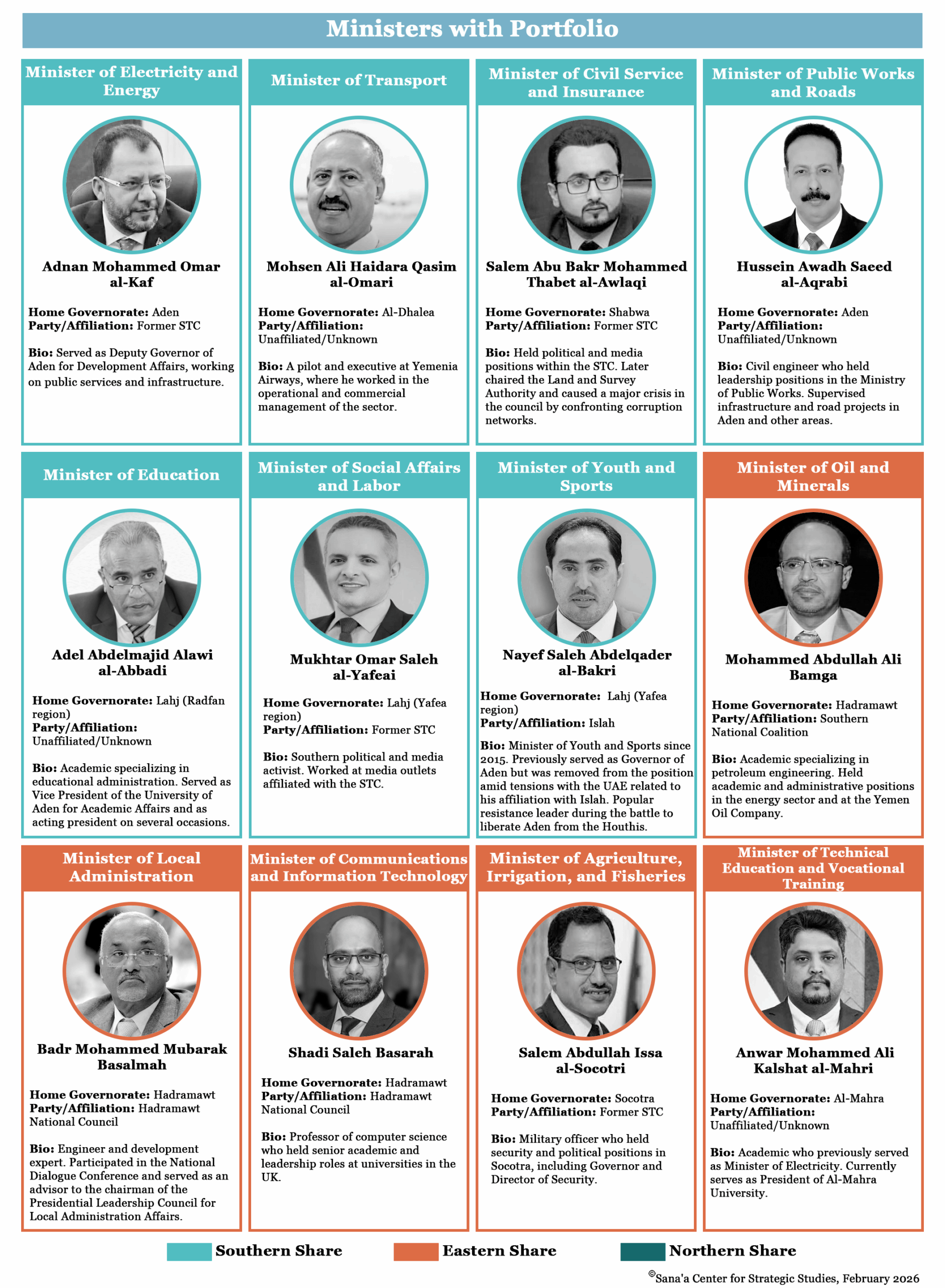

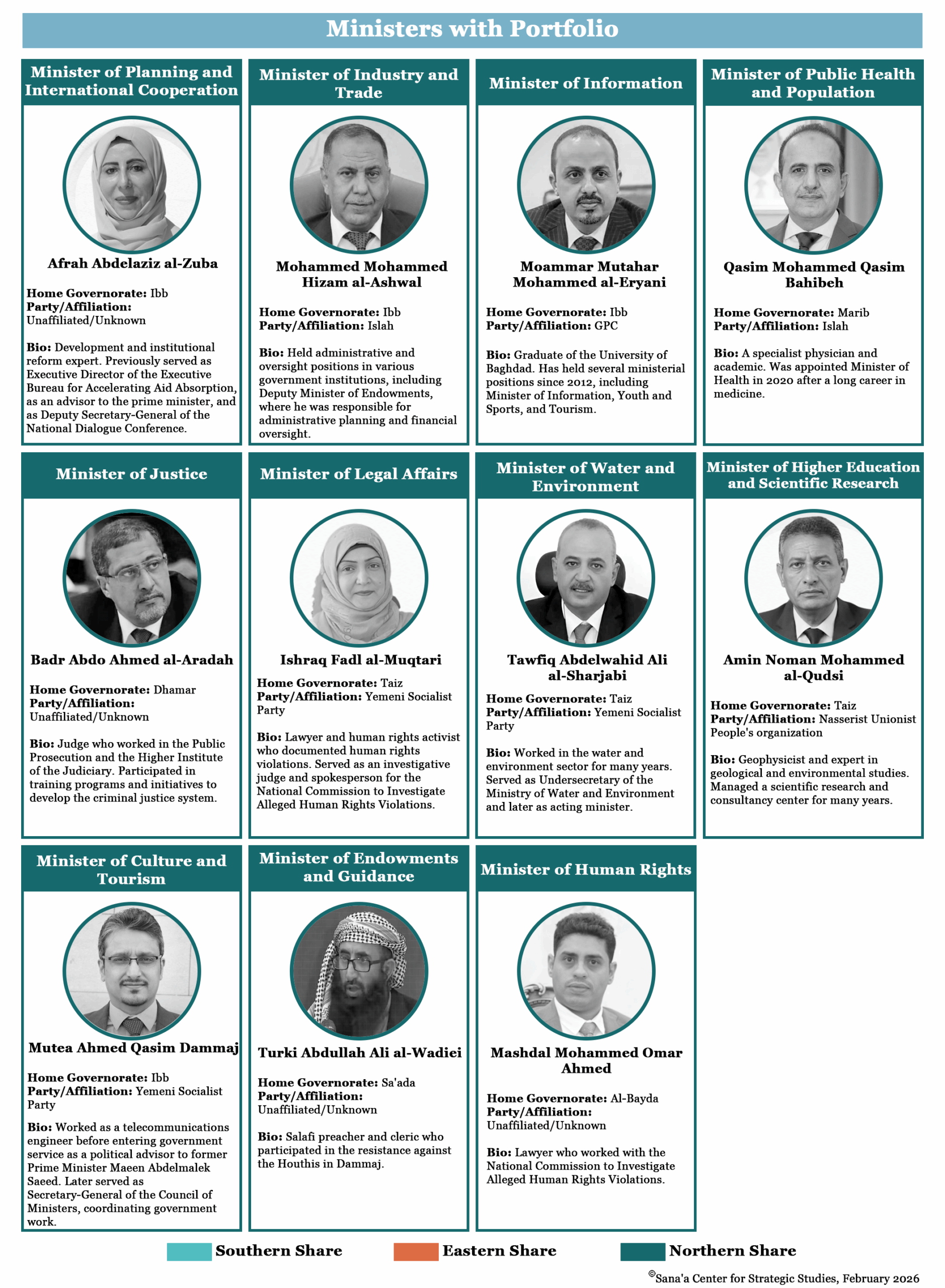

Three weeks after Prime Minister Shayea al-Zindani was tasked with forming a government, a notably large cabinet was announced, comprising 35 ministers, including eight ministers of state (see full list and bios below). Since the start of the war, Yemen has seen successive changes in the premiership without corresponding changes in the government, and the formation of quota-based cabinets in which the prime minister lacked the authority to appoint or dismiss ministers. Both factors have contributed to the weakness of successive governments.

Although Prime Minister Al-Zindani was formally tasked with forming the government, he had little control over the new cabinet’s composition. Decision-making authority rested largely with Saudi Arabia and Presidential Leadership Council (PLC) head Rashad Al-Alimi, with only limited influence from other political actors. The process sparked an open debate over quotas for the representation of political parties, with critics arguing that they affect the competence of nominees. In the past, parties prioritized loyalty over merit, contributing to low levels of public trust. Notably, the quotas for regional representation established for this government did not elicit similar objections, despite potentially being more dangerous, as they risk reinforcing the country’s division along regional lines.

The notion of a technocratic government has been advocated since 2014, yet it remains politically unrealistic in Yemen. In practice, government work lies at the heart of political activity, and it is possible to strike a balance between political loyalty and competence. The presence of political parties and other political actors has helped prevent unilateral decision-making and the reckless appointment of unsuitable nominees. Collective decision-making remains necessary, even if it lengthens and complicates the process.

A Distortion of Governance

Yemen’s war, now entering its second decade, has produced distortions in how public office and public engagement are perceived and practiced. First among these is the growth of rent-seeking by public officials, in which posts are treated as privileges devoid of responsibility. This partly explains the large number of ministers. This condition is also a product of the government’s prolonged presence abroad, as well as of the way those at the top have treated public office as a means of cultivating loyalty and rewarding certain individuals.

Second, influence in the public sphere is increasingly driven by individual reach and engagement through television and social media. This shift has coincided with a significant decline in the influence of traditional political and media outlets. This is compounded by policymakers’ growing obsession with media exposure and an increasing degree of political superficiality, driven by sustained detachment from the problems on the ground. Under conditions of political polarization, social media platforms have become arenas for mobilization and incitement, where all forms of falsehood, hate speech, and provocation are permissible. Like any populist tool, the loudest and most extreme voices tend to attract the greatest attention and followership.

Third, in recent years, governments have failed to secure public trust due to factors beyond their control. These include limited financial resources and the need to build institutions almost from scratch – the Yemeni state had been highly centralized in Sana’a for decades. Operating from Aden brought institutional challenges, including the absence of basic infrastructure and the loss of accumulated institutional experience. In the interim, some institutional structures and capacities have been developed, from which the new government may benefit.

The conflict, with its attendant divisions and the proliferation of armed factions on the ground, has also prevented the transfer of revenues to the government from profit-generating institutions. Government export revenues were cut off as a result of Houthi attacks targeting oil facilities, and the intensity of internal polarization further paralyzed its ability to function. In principle, the current situation has comparatively improved, as the Saudi-Emirati rift is no longer spilling over into Yemen and incapacitating the government.

Other forms of dysfunction are deeply entrenched, such as the rife corruption within Yemen’s governmental and political class, whose severity has been exacerbated by institutional weakness and the erosion of what remains of accountability and oversight mechanisms. While corruption is widely recognized for draining the state’s limited financial resources, an equally serious but less scrutinized issue is the inflated bureaucracy and its lack of competence. The excessive number of public employees places a heavy burden on the budget, while patronage-driven appointments drain limited resources and undermine the government’s capacity to perform.

Silver Linings and Charting A Path Forward

The new cabinet brings some positive changes, not least the representation of women. Since the formation of a government following the Riyadh 2019 agreement, there has been a noticeable lack of women. The new cabinet has three women ministers, one of whom serves as a minister of state. The hope is that women’s participation extends beyond token participation to recognizing their ability to drive meaningful change. Under the party quota system, political parties pushed to fill their allotted cabinet seats with men, deprioritizing women’s participation and producing some of Yemen’s weakest governments. The renewed presence of women and their appointment to major ministries, such as Legal Affairs and Planning and International Cooperation, has fueled hope that the government will move beyond questions of representation to tangible progress on issues affecting Yemeni women.

The current government has also been reinforced by a number of respected figures in Yemen, whose integrity and experience are expected to contribute to its performance and help address dysfunctions within a system deeply mired in corruption and compounded structural failures.

Despite ongoing discourse about parity between the North and the South, it is clear that the South has received a larger share of portfolios, particularly those of key and sovereign ministries. Some of these portfolios were allocated to recent members of the Southern Transitional Council (STC), which has now officially been dissolved. It is hoped that they have drawn lessons from the STC’s past mistakes and its opportunistic approach to power, marked by a disregard for the legitimacy of the state.

A decade of dysfunction and popular struggle can be the catalyst for meaningful reform. For this to happen, however, it is essential to revive the work of institutions tasked with combating corruption, which once monitored financial irregularities with a degree of transparency, as well as those responsible for public-sector appointments. Most critical of all is the reform of judicial institutions, which have become heavily politicized in recent years and have, since the outbreak of the war, suffered from division and disorder.

Reviving the work of the House of Representatives will be key. The legislative body should play an essential role in representing political and social forces and in overseeing the executive’s performance. The paralysis of the parliament stems from two main factors. First, its division and obsolescence—split between Sana’a and Aden, with no elections since 2003 —have left many members unable to fulfill their duties. Second, the security and political environment has prevented the convening of parliamentary sessions and the exercise of even basic functions, such as endorsing the government. This particular obstacle can now be overcome in the absence of the STC, which had previously blocked several attempts to hold sessions in southern Yemen.

Although staging parliamentary elections remains difficult due to security concerns and the inherent risks posed by widespread political polarization, this could be addressed through temporary measures, such as allowing local authorities to select and endorse representatives to political leaders.

The Yemeni state now needs to focus on overcoming its legacy of corruption and patronage, a legacy that the war has layered with polarization and practices embedded in political culture and conduct. Disentangling from this legacy will require considerable time and political will. The new government will test the state’s ability to assert its presence in areas under its control and to establish domestic legitimacy, not merely international recognition.

Finally, a lasting, peaceful settlement or effective military intervention will ultimately depend on the government’s successful restoration of state authority in Aden. Any development in Aden will remain limited in scope and duration unless it is part of a broader effort to address Yemen’s overall situation.

It is no exaggeration to say that this government may represent a last chance. The challenges are substantial, and the security situation is fragile; together, they create an environment conducive to rebellion and uncontrolled popular mobilization—dynamics that could deepen chaos and fragmentation in government-held areas. The expectations placed on this government are therefore at an all-time high.

This commentary is part of a series of publications produced by the Sana’a Center and funded by the government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The series explores issues within economic, political, and environmental themes, aiming to inform discussion and policymaking related to Yemen that foster sustainable peace. Any views expressed within should not be construed as representing the Sana’a Center or the Dutch government.