This year, Yemen experienced a series of weather shocks as flash floods swept through 15 governorates across Yemen between March 24 and June 6, affecting some areas multiple times. Considering that 80 percent of the Yemeni population is in need of some form of humanitarian assistance and more than 3.6 million people are internally displaced,[1] while public services and infrastructure have been laid bare during five long years of war, swathes of Yemen’s population are vulnerable to the immediate and long-term impact of these floods. This comes in the midst of a global pandemic, a continuing war and cuts in international aid to Yemen.[2]

The long-term impact of floods and natural disasters on the various sectors and overall GDP in Yemen are little understood, but some studies conducted following the 2008 Hadramawt floods indicate a lingering effect of such disasters on food security and household income. While agriculture is the sector worst hit by floods, others such as the service sector and food processing industries feel the shockwaves of such disasters.[3] According to the Climate Investment Fund, the 2008 floods inflicted damage amounting to 6 percent of GDP.[4]

Although rainfall in Yemen may be intense during its short spring and summer seasons, particularly in the Western highlands, an alarming change in weather patterns in the past decade has resulted in a higher frequency of flash floods and tropical cyclones, a novel weather phenomenon in Yemen. These are recurring in normally dry areas that received 50 mm of rainfall annually such as Hadramawt, Al-Mahra, Shabwa and Marib. In 2008, Hadramawt sustained long-term damage from floods that is still felt until today, according to Omar Shehab, the Director General of the Environmental Protection Authority in Hadramawt.[5] In 2015, the first tropical cyclone recorded since modern records began in the 1940s hit eastern governorates and the Socotra archipelago; two other cyclones occurred in 2018.

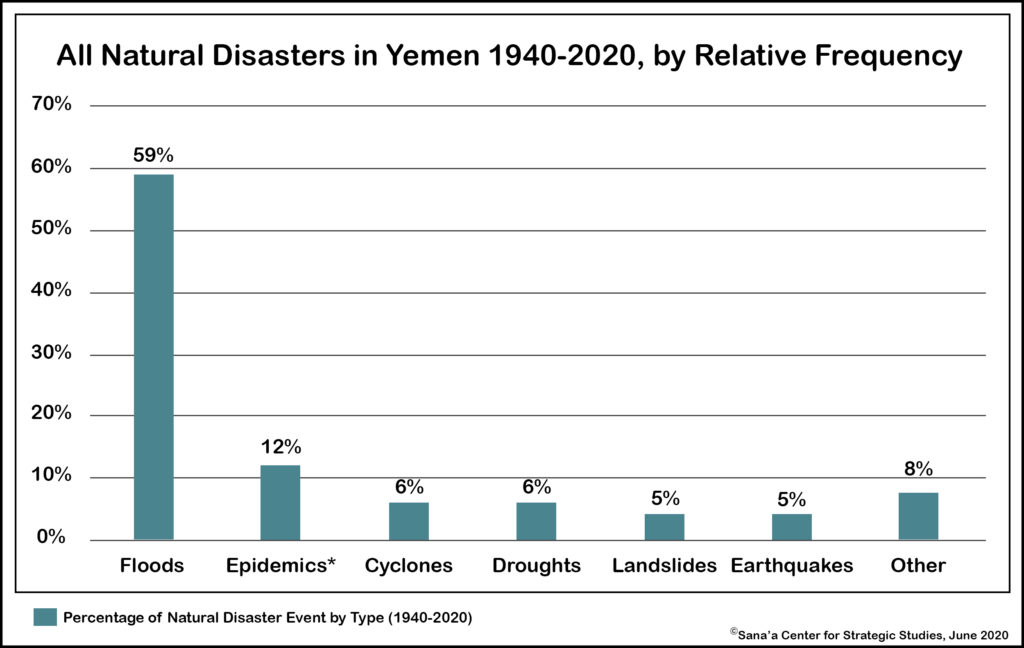

Extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and more intense, bringing Yemen face-to-face with a looming climate change emergency. Yemen is ranked 167 among 181 countries on the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) index in 2017, which measures countries’ vulnerability and readiness to face climate change.[6] Floods constitute the highest recurring natural disaster in Yemen; 39 floods happened between 1972 and 2020, making it an almost yearly occurrence and sometimes multiple floods occurred in a single year.[7]

Between March and June 2020, 150,000 people were affected by the floods, including 64,000 internally displaced people, and a further 7,000 became displaced within this period as a direct result of the floods.[8] According to a UN source, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to comment publicly, a network of local NGOs was mobilized including many volunteers to assess the damage and provide hygiene kits, food baskets and make-shift shelters to those who lost their homes. This was significantly hampered in April and June due to COVID-19 risks that restricted movement of humanitarian staff and aid. However, according to the UN source, “the biggest challenge is having a very weak national coordination body in the interim capital, Aden, that is absorbed in a political tit-for-tat.”

In ideal circumstances, the responsibility for rescue operations and disaster response coordination lies with the Civil Defense Authority, according to Yemen’s Law 24 of 1997 on the Civil Defense.[9] Fuad Ali, a UNDP Deputy Team Leader in the Economic Resilience and Recovery Team, said that civil defense received capacity building and support to respond to disasters prior to the war.[10] However, a source in the Civil Defense Authority in Sana’a said that their current work has been reduced to firefighting and basic rescue operations. The civil defense official explained that the agency does not have the capacity or resources for the wide range of responsibilities stipulated in the law or set in its disaster response plan.[11]

In Aden, the Civil Defense Authority has been almost stripped bare. According to the head of the Aden Civil Defense, Major General Mohammed Al-Shab’an, their offices were looted during the Houthi incursion in 2015. They now have no presence outside of Aden, are left with only a few firefighting vehicles and receive funds, often late, for operational costs that barely cover maintenance of vehicles and staff salaries. Al-Shab’an said no plan was in place to respond to the flooding disaster and there were no designated evacuation locations or capacity to evacuate people. “We tried our best given the limited resources available to us, such as driving our firefighting vehicles around the city to make public announcements for the residents to take the necessary precautions,” Al-Shab’an said, adding that the floods in Aden were especially devastating because of unplanned urban development as buildings blocked and redirected the path of flood waters. Water flow was further obstructed by security roadblocks that riddle the city, especially around high-value buildings such as the Central Bank of Yemen.[12]

Interviews with Aden residents convey some of what people experienced during these floods. Zahra’a Ali, 22, a sociology student and resident of Crater, one of the districts in Aden badly affected by the floods, described how the flood water picked up large rocks and debris as it carved its path through the mountains, becoming thick with garbage and mixing with an overflowing sewage system. In some areas, entrances to homes were blocked by a thick layer of silt carried by floodwater from the mountains, she said. The Al-Khesaf neighborhood, which houses marginalized communities in fragile tin houses, was essentially washed away. Crater’s old system for rainwater drainage known as manahel was ineffective as newly constructed buildings blocked them and flood water that became trapped in neighborhoods quickly turned into foul swamp water.[13]

According to another resident of Crater, Ayah al-Ebbi, 23, a student of laboratory sciences involved in community work, the flood response came primarily from youth activists, who appealed to local philanthropists to cover the high costs of vacuum trucks that drain water from residential areas. Al-Ebbi currently hosts her relatives who fled their home in April after losing all their furniture in the floods. She said that some local NGOs came to assess the damage and distribute hygiene kits and, while she praised local initiatives that swiftly mobilized in response to the calamity, she said the scale of the disaster required an official and coordinated response from the state. Nevertheless, Al-Ebbi said many residents were better prepared when floods occurred again on April 21, having sealed their homes, and immediately drained the water as it flowed.[14]

While residents spoke of some district heads responding quickly with whatever means possible, a video circulating on social media two days after the second round of floods showed the acting governor of Aden, Ahmed Salmin Rabi’, followed by residents in Crater demanding water and electricity and hurling obscenities at him.[15]

Al-Mahra is another governorate that has suffered from floods and cyclones in recent years. “People of Al-Mahra remember with horror the cyclone of 2018,” said Noor Makki, 28, a resident of governorate capital Al-Ghaydah who works at the Fisheries Authority, “so when meteorological warnings announced an atmospheric depression, we were on high alert and many people took shelter in the mountains.” Makki said that while the rains were not as severe as they had initially anticipated, they did affect certain areas prone to flooding where internally displaced people (IDPs) and newcomers had settled.[16] A similar situation devastated 3,500 IDP shelters in Marib governorate,[17] where the largest displacement site, Al-Jufaina, is located.[18] The Shelter Cluster, the inter-agency coordination body co-chaired by UNHCR and IOM and responsible for coordinating IDP shelter management and aid distribution, was unresponsive to multiple Sana’a Center requests for comment.

Building on flood courses is also a problem in Hadramawt, according to Dr. Khaled Bawahedi, an associate professor at the Faculty of Environmental and Marine Sciences in Hadramawt University. “The local government continues to tolerate the construction of houses on flood courses and valleys, with complete disregard to the risks this poses to the population — often to IDPs and poor communities. During this round of floods and also during previous floods, some communities were deprived of clean water – this is what happened in Al-Hajr, one of most badly hit areas in Hadramawt,” he said. Bawahedi sees a clear link between these weather shocks and climate change, but said higher education institutions’ resources to research and share knowledge on adaptation and mitigation are limited and official support is lacking for this type of work.[19] Omar Shehab said the Environmental Protection Authority he leads in Hadramawt was shut down from 2013-2017, and that funding for research and even basic field data collection is non-existent.[20]

In discussions with people from some of the affected governorates, one gets the impression that each operates in isolation; there is no sense that climate change-related disasters cross not only governorate lines but national and international borders. According to Anwar No’man, an environmental scientist who has been working on climate change in Yemen since 1996, Yemen is party to the main international environmental treaties and has taken some steps in adaptation and mitigation. In 2009 it developed a National Adaptation Program of Action and continued to submit periodic reports to the parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the latest of which was in June 2018. However, development and climate change projects were sidelined during the war as donors shifted their focus and funds to short-term humanitarian aid. “Climate change action is an emergency that requires long-term commitment,” No’man said. When asked about whether communities are aware of climate change, he explained, “Farmers are becoming aware of a shift in seasons and rain pattern disruptions. They might not be aware of concepts such as climate change and global warming, but they understand from first-hand experience that nature is changing and it’s causing their crops to fail.” [21]

This year’s floods, an emergency requiring an immediate response on par with humanitarian emergencies caused by the war, are also part of a global emergency that requires a coordinated long-term commitment. There is no sign that the intensity of rains and cyclones will be abated; on the contrary, they are expected to become more extreme. Communities and local governments require the tools and knowledge to adapt to such disasters and to understand the risks of redirecting rainwater without proper planning. The frequency of floods in Yemen should make flood risk reduction in IDP sites a priority, especially as several IDP sites are situated in high-risk areas.. The risk of floods remains high in Yemen for the upcoming months as the rainy season may stretch until October.

This environment bulletin appeared in Struggle for the South – The Yemen Review, June 2020

Yasmeen al-Eryani is a non-resident fellow at Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies and a Ph.D candidate in Social Anthropology at Tampere University in Finland, where her research focuses on education practices during armed conflict in Yemen. She tweets @YEryani

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover diplomatic, political, social, economic and security-related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Endnotes

- “Yemen Situation Report”, UNOCHA, June 2, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Situation%20Report%20-%20Yemen%20-%203%20Jun%202020%20%281%29.pdf

- Vivian Yee, “Yemen Aid Falls Short, Threatening Food and Health Programs,” New York Times, June 2, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/02/world/middleeast/yemen-saudi-united-nations-aid.html

- Manfred Wiebelt; Clemens Breisinger; Olivier Ecker; Perrihan Al-Riffai; Richard D. Robertson, and Rainer Thiele, “Climate change and floods in Yemen: Impacts on food security and options for adaptation,” International Food Policy Research Institute, IFPRI Discussion Paper 1139, Washington DC, 2011. http://ebrary.ifpri.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15738coll2/id/126748

- “Strategic Program for Climate Resilience for Yemen”, Climate Investment Funds, April 30, 2012, https://www.climateinvestmentfunds.org/country/yemen

- Sana’a Center interview with Omar Shehab, Director General of the Environmental Protection Authority, June 23, 2020.

- Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN), 2017, https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/

- The Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, June, 2020, https://public.emdat.be/data

- “Emergency Plan of Action: Yemen”, The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, April 28, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/MDRYE009.pdf

- Yemen national law (24) on civil defense, April 6, 1997, https://yemen-nic.info/db/laws_ye/detail.php?ID=11524

- Sana’a Center interview with Fuad Ali, Deputy Team Leader of the Economic Resilience and Recovery Team, UNDP, June 21, 2020.

- Sana’a Center background interview, not for attribution, with an official in Civil Defense, Sana’a, June 23, 2020.

- Sana’a Center interview with Major General, Mohammed Al-Shab’an, Head of the Civil Defense Authority, Aden, June 22, 2020

- Sana’a Center interview with Zahra Ali, a resident of Crater, Aden, June 22, 2020

- Sana’a Center interview with Ayah Al-Ebbi, a resident of Crater, Aden, June 22, 2020

- Azouz Jamal, Facebook, April 23, 2020 https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=3765275230181682&id=100000977258408

- Sana’a Center interview with Noor Makki, resident of Al-Ghaydah, Al-Mahra, June 22, 2020

- “Displacement in Marib”, IOM-Yemen, April 22, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/en_iom_yemen_displacement_in_marib_22_april_2020.pdf

- “Al Jufainah Camp, Marib City: Camp Profiile”, IOM-Yemen, February, 2020, https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/situation_reports/file/en_iom_yemen_jufainah_camp_marib_city.pdf

- Sana’a Center interview with Dr. Khaled Bawahedi, Associate Professor in the Faculty of Environmental and Marine Sciences, Hadramawt University, June 23, 2020

- Sana’a Center interview with Omar Shehab, Director General of the Environmental Protection Authority in Hadramawt, June 23, 2020.

- Sana’a Center interview with Anwar No’man, environmental scientists and Yemen climate change expert, June 22, 2020