The Sana’a Center Editorial

The Sana’a Center Editorial

Hadi Must Go

Yemeni President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi is doing his best to prevent an end to the conflict in Yemen. Ensuring that last year’s Riyadh Agreement – meant to mend divisions with his rivals in southern Yemen – never gets implemented is only his latest venture in this regard. Hadi’s tenure has been a case study in parasitic statesmanship, in which only his amoral pursuit of riches and self-preservation has been able to rise above his ineptitude. During his presidency, now in its ninth year, he has overseen Yemen’s steady dissolution from a nation hoping to transition to democracy post-Arab Spring, to a nation fragmented by civil war and regional military intervention, to a land of warring statelets, mass suffering and despair. Enough – it is time for Hadi to go. Once this clear necessity is acknowledged by all concerned parties – in particular Saudi Arabia, his patron, the United Nations Security Council, which bestows on him international legitimacy, and the shrinking number of Yemeni actors who ally with him for lack of better options – then the conversation can shift to how to replace him.

At a basic level, Hadi never had the qualities associated with successful leadership. Former President Ali Abdullah Saleh appointed Hadi his deputy following the 1994 civil war because the latter – showing little in the way of managerial competence, decisiveness, charisma or vision – posed little threat to Saleh’s rule. Hadi was a senior southern military figure who fled north following his side’s defeat in the 1986 South Yemen Civil War and then allied with the Saleh regime in the 1994 north-south civil war, all of which helped to make him a highly divisive figure with little natural constituency. In the south he is widely regarded with suspicion and contempt. In the rest of the country, he is viewed as a nobody.

Hadi’s claim to the presidency is also tenuous. Following the 2011 Yemeni uprising, the internationally-backed Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) initiative facilitated Saleh’s exit from office and Hadi’s ascent, with the latter’s popular mandate of a two-year transitional term affirmed in a one-candidate ‘election’ in 2012. Hadi subsequently oversaw the nearly year-long National Dialogue Conference, which was meant to bring Yemen’s various factions to a consensus on how to address the country’s most pressing issues. He then overstepped his mandate and torpedoed the transition by attempting to impose a six-region federation of Yemen that many see as the catalyst for the current armed conflict. Hadi’s two-year term was extended for one year in 2014. Following the Houthi forces’ invasion of the capital in September of that year, Hadi’s flight south and eventually to Riyadh, and the regional military intervention in March 2015, his term as president became indefinite and unaccountable to the Yemeni people.

Hadi’s legitimacy to head Yemen’s ‘internationally recognized government’ is almost wholly conferred by the UNSC and the international community through UNSC Resolution 2216, which recognizes him as the legitimate president of Yemen in the wake of the Houthi takeover of Sana’a. His legitimacy is entirely detached from his performance as a head of state. Riyadh, meanwhile, for the most part sees Hadi as useful for providing international legal cover for its military campaign in Yemen, and little else. This lack of accountability has allowed Hadi’s presidency to metastasize into a government in exile that serves primarily as a vehicle for corruption.

Hadi’s small inner circle, made up of his sons and powerful figures from his home governorate of Abyan, are far from the only figures profiting from the conflict, but given their placement atop the government hierarchy, the scope and scale of their corruption are exceptional. The continuity of this graft is dependent on Hadi maintaining the presidency, while at the same time any negotiated end to the war will likely require Hadi to transition out of power. Knowing this, the president and his circle’s vested interests are tied to the war continuing, removing any incentive to compromise during negotiations, whether with the Houthis or nominal allies in the anti-Houthi coalition.

In 2016, Hadi scuttled UN-sponsored peace talks in Kuwait. By firing then-Vice President Khaled Bahah – seen as a potential compromise candidate the warring parties might agree on to replace Hadi – and appointing General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, a figure widely reviled across Yemen, he derailed negotiations and ensured no deal would be reached to replace him. By 2017, his government’s failure to provide basic public services in southern Yemen, and his personal targeting of rival southern leaders, led to the formation of the Southern Transitional Council (STC). Backed by the United Arab Emirates, the STC quickly began challenging Hadi for dominance in the south and splintered the common front against the Houthis. This rivalry broke out into open hostilities when STC-affiliated forces drove the Yemeni government out of Aden in the summer of 2019. With clashes again raging in the south, Hadi, the southerner exiled in 1980s South Yemen power politics, has made Abyan’s war the Republic’s war.

The Saudi-sponsored Riyadh Agreement in November 2019 was meant to mend the divide by integrating the STC into the Yemeni government both politically and militarily, in exchange for the STC having representation in the government delegation at any future UN-sponsored negotiations to end the war. Had genuine reconciliation been Hadi’s motivation, he could have eased tension with the STC by incorporating members into his government and demonstrating that he could be their president as well. But as per form, Hadi made no such concession, instead prioritizing a historic local feud over the good of the country.

Today, STC influence in the south is expanding as Hadi shrinks further into exile in Riyadh, leaving Yemenis facing the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic without functioning state institutions to provide them even basic assistance. If the past eight years are any guide, maintaining the political status quo will entail continued failures in governance, further political and social division and unending war for Yemen.

Efforts to put Yemen on a better path politically must start without delay, and the change should begin at the top. The main parties within the anti-Houthi coalition should realize the president is beholden to them, not the other way around, and recognize the Yemeni government can be stronger without him. The parties that signed the GCC initiative and claim to commit to a real political transition for Yemen need to decide whether they are serving Yemen or Hadi.

The Saudis, meanwhile, are well aware of their dysfunctional relationship with Hadi. Ending support for him is both rational and an outside-the-box move to begin repairing the fractured anti-Houthi coalition. Backing the replacement of the ineffectual Hadi with a presidential council, representing the coalition’s main Yemeni parties, would be a major, and necessary, step in the right direction.

This bold move will need to be met with clear support from the international community through a new UNSC resolution reflecting the realities in Yemen. The UN claims its current framework responds to threats to peace in Yemen. Hadi has become such a threat and the UNSC should be glad to see the back of him, just as most Yemenis will be.

While pursuing alternatives to the Hadi presidency would carry risks, the current track should, to Yemenis and all concerned stakeholders, be unpalatable. Given the extent of elite capture in the executive office, diluting Hadi’s power or replacing him with a single figure would not create the conditions for effective leadership at the head of the Yemeni government to emerge. Rather, a presidential council that offers representation to the various political parties is likely the only viable option to both balance their vested interests and garner enough buy-in to begin reunifying areas of the country outside Houthi control. A more cohesive Yemeni government might then have some chance at developing the institutional capacity to provide for the population, and also be able to put forward a representative delegation for negotiations with the armed Houthi movement to end the wider war.

Contents

- The Struggle for the South

- On the Houthi Front

- Economic Developments

- The COVID-19 Pandemic

- Environmental Developments

- Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments

- In the Region

- Commentary: The United Nations Security Council: From Participant to Passive Observer in Yemen

- In the United States

With apparent fuel shortages gripping Houthi-held areas of Yemen last month, queues at gas stations in the Sana’a were seen extending for kilometers on June 17, 2020. For full coverage see: Another Stage-Managed Fuel Crisis in Northern Yemen // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

Developments in Yemen

The Struggle for the South

STC-Backed Forces Seize Socotra

On June 20, the secessionist Southern Transitional Council (STC) seized control of the island governorate of Socotra, overthrowing the Yemeni government-backed local authority. The Yemeni government, which is also battling with the separatist forces in Abyan, labeled the STC’s takeover as yet another coup.[1] The two sides are involved in a power struggle in southern Yemen, which escalated with the STC’s declaration in late April that it would institute self-rule in governorates that were part of the former South Yemen.

The takeover in Socotra began with STC-aligned forces capturing governorate facilities and military bases in the capital, Hedebo. The Saudi-led coalition, which has troops stationed on the island and had previously brokered an agreement to end the fighting on the island,[2] attempted to pressure the STC to halt its offensive, but the group refused to do so. Saudi troops did not move, however, to stop the separatist forces. Instead, Ramzi Mahrous, the Yemeni-government appointed governor of Socotra, accused Saudi Arabia, along with the United Arab Emirates, of letting the STC move into positions that the Yemeni army had withdrawn from as part of negotiations to deescalate the fighting.[3] Saudi forces sheltered Mahrous and several other officials loyal to the government of President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi before facilitating their evacuation to Al-Mahra on the Yemeni mainland.[4] According to Sana’a Center sources, Saudi forces remained in control of Socotra’s airport and the island’s main seaport.

On June 22, the STC moved to stamp its influence by appointing a new governor, Raafat al-Thaqali.[5] It also expelled Yemenis native to the country’s north from the island, accusing them of being mercenaries for the Hadi government, while granting an amnesty for any southern opponents.[6] The STC now controls the local authority in four southern governorates – Socotra, Lahj, Al-Dhalea, and Aden – granting the group access to locally-generated revenues and providing it additional leverage in Saudi-backed negotiation efforts to end its rivalry with the Yemeni government.

Saudi-Announced Cease-Fire and Govt-STC Talks Fail to Halt Abyan Fighting

Yemeni government and STC-backed forces clashed throughout June in Abyan governorate, undeterred by the Saudi-led coalition’s June 22 announcement of a cease-fire negotiated by political leaders of both sides in Riyadh.

Clashes centered in the Sheikh Salam area, with STC forces looking to push east toward the coastal town of Shaqra and government-backed troops trying to move west to the governorate capital, Zinjibar, which sits on the road to Aden. Fighting also continued around the town of Al-Jaar, north of Zinjibar.[7] Casualties have been high in the governorate, with 85 dead on both sides reported June 11,[8] and a further 54 killed during a 24-hour-period on June 24.[9] Despite the attrition, neither side has gained substantial territory.

Saudi-led coalition spokesman Turki al-Maliki had announced that the government and STC had agreed to a cease-fire on June 22. Saudi troops were also deployed to Abyan to monitor the cease-fire and establish a mechanism to deal with violations. However, the agreement remains marred by distrust, with both sides accusing the other of violating the truce.[10] Saudi Arabia is also sponsoring talks between the STC and Yemeni government leaders in the Saudi capital intended to implement the Riyadh Agreement, the November 2019 deal that ended a previous round of fighting in southern Yemen and laid out a path for the STC to be integrated politically and militarily within the Yemeni government. However, the deal was never put into place, mainly because of disagreements over the order in which aspects of the agreement would be implemented. The STC has pushed for political elements of the agreement – such as the formation of a unity government and the naming of a new governor for Aden – to take precedence, while the government insists first on the security element, which includes the redeployment of troops to pre-August 2019 positions and the STC placing its forces under the command of the Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Interior. It remains to be seen whether the Riyadh Agreement in its current form is salvageable. STC leaders told The Associated Press that while the council is open to the negotiations, it is standing by its self-rule declaration.[11]

The Riyadh Agreement Dilemma

A key obstacle to nationwide peace negotiations is the formation of a Yemeni government delegation that includes the Southern Transitional Council (STC). This was meant to be a key outcome of the Saudi-brokered Riyadh Agreement the two rival parties acceded to last year. As it stands, however, successful implementation of the Riyadh Agreement requires redeploying forces loyal to Yemeni President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi in Aden, his government’s interim capital, risking renewed bloody confrontations with STC-affiliated forces that would wreck the peace negotiations. This is the dilemma of the Riyadh Agreement.

On November 5, 2019, the Internationally Recognized Government of Yemen (IRG) and the Southern Transitional Council (STC) signed an agreement in Riyadh to end their military confrontations. These had raged in Aden and other southern governorates over the previous months and led to the expulsion of President Hadi’s forces from the city. The agreement – styled in the model of the 2016 Kuwait talks between the IRG and the de facto Houthi authorities of Sana’a – stipulated the return of the government to Aden, a power-sharing arrangement and the integration of STC military and security forces into the government armed forces and Ministry of Interior. Upon achieving that, the STC will be included in the national cabinet and any future government delegation to negotiate a nationwide cessation of hostilities with the armed Houthi movement, also known as Ansar Allah, who hold Sana’a and most of Yemen’s north.

Since then, implementation of the Riyadh Agreement has been frustrated by disagreement on the sequencing of implementation, an issue that is often cited as the reason for scuppering the proposed 2016 Kuwait Agreement. The STC insists on appointing a governor and a chief of police for Aden before it redeploys its forces out of the city; Hadi insists on the opposite. Distrust and demonstrably bad intentions on both sides have poisoned the implementation talks. While the two sides profess compliance, they continue to take military actions that belie their rhetoric. Fighting has continued on and off since November, with the STC escalating its rhetoric against Hadi and his government, claiming that Hadi is merely a pawn for northern terrorists (a reference to Hadi’s governing ally, the Yemeni Congregation for Reform, better known as Islah) and occupiers. Hadi’s side, on the other hand, has continued to build up its forces and move units from Marib and Hadramawt to increase pressure on the STC.

The Saudis, who rammed this agreement down the throat of both sides, seemed to have skipped their history lesson. Instead, they bought into the prevailing narrative that presents this conflict as one between a faction, supposedly dominated by northerners, who wish to preserve Yemeni unity, and southerners who are trying to rid themselves from northern domination and restore their old state. Pundits, meanwhile, note the competition between Saudi Arabia and the UAE. They also point out the declared target of the UAE to eliminate Islah. While valid, none of these characterizations captures the nuances of reality.

To understand the nature of the conflict between the Hadi government and the STC, one has to go back to January 1986. Rival factions within the Yemen Socialist Party that governed South Yemen fought a short but very bloody civil war in Aden that claimed more than 10,000 lives in two weeks. Broadly speaking, the conflict pitted two components of southern society against one another: the pastoralists of eastern Abyan and Shabwa (referred to as the Bedouins); and the farmers and warriors of Lahj and Dhalea (referred to as the Tribesmen). The fighting in 1986 was not a lone confrontation between these two distinct groups – it dates far back into history – but it was the most violent. The conflict ended with the defeat of the Abyan/Shabwa Bedouin faction and the expulsion of tens of thousands of its members – including President Hadi – to North Yemen and beyond.

This type of identity conflict is common in Yemen, and society had developed an elaborate tribal code to cope with such conflicts and mitigate their impact. However, Yemenis were shocked at the viciousness and lack of compromise of the 1986 conflict in Aden. Two factors explain its severity. In 1972, the Yemen Socialist Party (then led by the Abyan faction) adopted the Maoist model of socialism and nationalized private businesses, including small ones. Access to state jobs was the only source of livelihood left. Therefore, losing a power struggle was no longer a setback of earnings potential; it became a matter of survival.

Further exacerbating that situation, the YSP organized peasant uprisings beginning in 1972 against landowners and traditional leaders. Sultans, sheikhs, clerics and businessmen – society’s depository of traditional wisdom, accumulated over thousands of years, of conflict management and mitigation – were killed, imprisoned or chased away. In such a traditional society, where modern legal institutions and structures had not yet evolved, that action was tantamount to the society decapitating itself. So conflict could no longer be mitigated as it used to be, or as it continued to be in North Yemen.

In the aftermath of the 1986 civil war, the Bedouins, then derogatorily referred to as Zumra (liberally translated as “desperate band”), were uprooted and their homes were confiscated and occupied by the victors. They ended up in exile in North Yemen, where many were integrated into the armed forces, forming 15 brigades called the Unity Brigades. Along with president Hadi, most of his inner circle were among the survivors of that conflict.

When North and South Yemen agreed to unify in 1990, the winners of the 1986 conflict, the tribesmen, derogatorily referred to as the Toghma (liberally translated as the “Ruling Clique”), demanded that their Zumra enemies be kicked out of Sana’a. President Saleh complied and former president Ali Nasser Mohammed had to leave Yemen, while his colleagues had to disperse in distant governorates such as Sa’ada. Hadi, then viewed as an insignificant exiled officer in the department of military supplies, was spared exile but had to move to Hajjah for a few weeks.

In 1994, a simmering confrontation over the implementation of the unity agreement between President Ali Abdullah Saleh and Ali Salem al-Beedh, the former president of South Yemen who assumed the vice president’s post in the unified Republic of Yemen, erupted into a brief civil war. The three month conflict ended with Saleh’s forces marching victoriously into Aden, with the Unity Brigades the spearhead of that army. Saleh made sure to have Southern leadership of the military campaign into southern territories, so he appointed Hadi, the least illustrious southern commander, as Minister of Defense. As expected, upon taking Aden, Saleh allowed his northern tribal allies the opportunity to loot government property, and sent several top businessmen, including Mohammed Adhban and Saleh al-Murshed, to buy back the loot on behalf of the government. Meanwhile, many exiled southern officers of the Unity Brigades went after their former rivals in the south, seizing their private homes and killing many of them. Most of the atrocities that took place in Aden in 1994 were payback for 1986.

Representation of southern Yemen after the conflict was monopolized by Hadi’s group, the Zumra. The Toghma, who represented a majority of the people of the South, were largely marginalized. For years, military and security officers of the Toghma were out of work and often out of livelihoods. Domestic and international pressure forced Saleh to pass decrees to reintegrate them into the national army. Still, Saleh’s behavior from 1986 until he resigned in 2012 indicated his intentions to continually undermine the South.[12] He appointed Hadi as head of a presidential committee charged with reintegrating forcibly discharged southern officers, knowing full well that Hadi would do his utmost to obstruct its implementation to punish his former enemies. In 2001, Saleh tried to tinker with the Zumra monopoly on southern representation by courting some Al-Dhalea figures and firing one of the Zumra’s most powerful figures, then-Minister of Interior General Hussien Arab. In response, the Zumra announced a political coalition, Caucus of the Sons of Southern and Eastern Governorates, that threatened to call for southern independence. The Zumra were no more pro-unity than the Toghma, but rather had used their alliances with northern forces and the central government in an effort to marginalize their southern competitor.

This history should make it clear that the struggle for southern Yemen is not merely a political conflict – it is a conflict of identities. Southerners, especially the Toghma-affiliate STC, are doing themselves a disservice by presenting the conflict as one between the South and the North, as denying the real dynamics of the discord makes its resolution impossible. In turn, attempting to implement the Riyadh Agreement without dealing with the underlying causes of the STC-Hadi government rivalry will only complicate the situation. The defeat of Hadi’s forces and their expulsion from Aden in 2019 served to defuse longstanding tensions in the city. Bringing them back, refilling the powder keg, no matter how clever the redeployment plans are, will risk a much worse bloodshed than happened last year – remember 1986.

Still, successful implementation of the Riyadh Agreement is seen as a prerequisite for progress toward negotiations for a nationwide cessation of hostilities. In reality, the best option to halt the current violence and maintain a fragile peace would be a modified version of the accord. On the security front, it could stipulate that the forces from each side stay in place and apart, with a token police force in Aden. STC-aligned forces could still be integrated onto the payroll of the government, addressing a major grievance of the group related to funding. Meanwhile, to avoid tensions in Aden, the seat of government could be relocated to the more pro-government confines of Sayoun or Mukalla in Hadramawt, or Al-Ghaydah in Al-Mahra.

In this way, the struggle over southern Yemen would be temporarily defused. The underlying cause of the conflict in the South, meanwhile, could then be deferred to the national reconciliation effort that must take place after the war, in a similar manner to what needs to be done in with Houthi authorities in Sana’a at the national level.

Abdulghani Al-Iryani is a senior researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies where he focuses on the peace process, conflict analysis and transformations of the Yemeni state. He tweets at @abdulghani1959

Violence in the South Spreads to Shabwa

East of Abyan, hostilities in Shabwa escalated between STC- and GoY-aligned forces against the backdrop of ongoing tribal disputes. Clashes erupted after the government’s Special Security Forces (SSF), which are aligned with the Islah party, attempted to block the local STC leadership and tribes in Jerdan district from holding a meeting to discuss developments in the south. A member of Al-Dabab tribe was killed during the clashes, which involved the use of heavy weapons, prompting tribal forces to block the SSF from returning west to the governorate capital Ataq. Calm was restored through tribal mediation and the Sana’a Center confirmed an agreement was struck for the SSF to withdraw from Jerdan district, for each side to release captured soldiers and for the formation of a fact-finding committee.

The next day, further clashes erupted in Nissab district, between tribes and the SSF related to the killing in May of Talal al-Awlaqi, a soldier in the STC-aligned Shabwani Elite Forces. Local tribes had called for accountability and the SSF’s departure from Nissab, with the STC declaring support for the Al-Areeq tribe. On June 12, Al-Areeq tribal forces, gunmen from tribes loyal to STC and some members of the Shabwani Elite Forces attacked and besieged SSF positions in Nissab city. STC-aligned forces took control of half of the city, including markets and government buildings. In response to the clashes, roads were cut and both sides rushed to bolster their forces, with the government’s 21st Mechanized Brigade and other forces moving from Bayhan district toward Nissab and tribal and STC-aligned forces also mobilizing reinforcements toward the city. However, by June 20, clashes between the two sides had largely subsided in Nissab.

On the Houthi Front

Houthis Squash Tribal Uprising in Al-Bayda, Push into Marib from the South

In June, Houthi forces suppressed a challenge from local tribes in Al-Bayda. Tension had been rising in the strategic central governorate – which borders four northern and four southern governorates – since late April after Houthi forces killed a local woman during a raid. In response, Yasser al-Awadi, a local tribal sheikh and member of the General People’s Congress (GPC), called on local tribes to band together, demand justice for the killing and expel Houthi supervisors. The Houthis had sent leaders to negotiate with the Al-Awad tribe in May while also continuing battles in Al-Bayda with pro-government forces that had pushed forward in the Qaniyah district along the border with Marib.[13] As mediation efforts failed to quell the dispute, the Houthis dispatched additional troops to Radman al-Awad district at the end of May.[14]

On June 17, Houthi forces moved against Al-Awad tribe, launching missiles and drones and clashing with tribal forces in Radman al-Awad.[15] The fighting was short-lived, with the Houthis putting down the challenge in roughly 24 hours of clashes. The group seized the market and center of the district, along with Yasser al-Awadi’s home, forcing him to flee to neighboring Marib.[16] According to Sana’a Center sources in Al-Bayda, the uprising failed in part due to a lack of military planning and to dissent within the tribe, with some elements that were dissatisfied with Yasser al-Awadi’s administration of the tribe in the past using the opportunity to double cross him.

The tribal uprising in Al-Bayda also suffered from a lack of support from the Yemeni government and the Saudi-led coalition. This had been a factor in previous failed tribal uprisings against the Houthis. The Hajjur tribe had risen up against the Houthis in February 2019, and despite the Yemeni government saying that it would send forces to bolster the tribal forces in Hajjah governorate, the Houthis managed to quell the challenge, killing a Hajjur tribal elder and later carrying out a campaign of mass arrests in the governorate.[18]

By the end of the month, Houthi forces claimed to have regained control of all of Ramdan al-Awad and the Qaniyah front to the north, including parts of neighboring Mahliyah and Al-Abidiah districts in Marib and the main road connecting the two districts that had served as a key government supply line. Pro-Houthi media, citing Houthi military spokesperson Yahya Sarea, reported that more than 400 square kilometers was captured by the group.18 According to a Sana’a Center observer in Marib, government and tribal forces were forced to retreat to Al-Abdiah district to the east while the Saudi-led coalition attempted to stem the Houthi advance with airstrikes.[19]

Meanwhile, fighting also increased in the northwest of the governorate, with Houthi forces attacking government positions on Mount Haylan in the Serwah front, and battles also continuing in Majzar district as well as in Al-Jadaan, to the north of Serwah. [20]

On June 29, a Yemeni army unit carried out a raid in Al-Khashaa, Wadi Ubaida, Marib city, that resulted in the death of at least half a dozen members of Sabaian family.**

Frontlines Active Across the Country

Fighting between Houthi and anti-Houthi forces flared on frontlines in multiple other governorates, including Al-Dhalea, Lahj and Taiz. Clashes in Al-Dhalea were mostly focused in the Al-Fakhir area in Qatabah district and along the Al-Azariq front on the border with neighboring Taiz governorate. In Lahj, STC-affiliated Southern Resistance forces attacked Houthi forces in Al-Hadd Yafa district on the border with Al-Bayda governorate. Houthi forces cut supply lines between Lahj and Al-Bayda, which had been used by the Saudi-led coalition’s military command in Aden to provide military and financial support to Al-Bayda’s local Popular Resistance. Fighting in Hadd al-Yafa centered around Al-Jamajim Mountain, which is currently held by Southern Resistance forces. Houthi forces, seeking to take advantage of the redeployment of STC-aligned forces to Abyan governorate, attacked the area with artillery and heavy weapons and seized some positions. In Qabaytah district in the west of the governorate, Houthi forces battled an alliance of Yemeni government forces affiliated with the Fourth Military District and the STC-affiliated Security Belt forces and Fifth Support and Backup Brigade.

Meanwhile, in Taiz, clashes involving shelling, gunfire and sniping occurred in Taiz city and in various other frontlines in the governorate. Intra-coalition tensions persisted in Al-Hujariah region between the Islah party, forces loyal to Tariq Saleh, and the General People’s Congress branch affiliated with the Speaker of the Parliament, Sultan Al-Burkani.

Renewed Saudi-Houthi Air War

Multiple drone and missile attacks by the Houthi movement on Saudi territory in June harkened back to the regular cross-border strikes witnessed in 2019 before the two sides agreed in September to a cease-fire on aerial attacks. On June 16, Houthi military spokesperson Yahya Sarea announced on Twitter that the group had carried out drone strikes against Khamis Mushait in southern Saudi Arabia,[24] while the Saudi-led coalition said it had intercepted a ballistic missile fired toward Najran province.[25] Later in the month, Sarea claimed that Houthi forces had targeted a Saudi Ministry of Defense building, the King Salman air base and an intelligence building in Riyadh on June 22. Coalition spokesperson Turki al-Malki announced Saudi air defenses had intercepted a ballistic missile fired toward the Saudi capital.[26]

Inside Yemen, the Saudi-led coalition also continued its campaign of aerial bombardment. Saudi-owned Al Arabiya reported that a high-ranking Houthi commander in charge of the movement’s explosive drone production was likely killed in airstrikes on the Nehm front in eastern Sana’a governorate along the border with Marib. The Houthis had acknowledged the death of Mohammed Abdo Musleh al-Ghouli on June 14, but did not provide any details on how or where he had been killed.[27] On June 16, at least five airstrikes were carried out in the capital Sana’a. A day earlier, the Houthis said a strike against a civilian vehicle in Sa’ada had killed 13 people, including four children, though the Saudi-led coalition denied the report.[28]

The Houthis from the Sa’ada Wars to the Saudi-Led Intervention

The Houthis, a religious Zaidi movement that is limited to Yemen, have expanded their rhetoric to more closely reflect ideas espoused by Iran and other Shia Islamist movements in the so-called ‘Axis of Resistance’, yet the group’s nature remains highly local, based on ancestral and territorial history. One cannot easily join the core Houthi movement because it does not trust anyone who joined after it expanded beyond Sa’ada and became the ruling power in Sana’a. Relations between the movement’s members are based on absolute loyalty to the leadership and complete faith in the inevitability of reaching the movement’s goals. The group’s faith in its own purity has led to a sense of superiority over others and distrust of outsiders.

Understanding the Houthis requires distinguishing between their true internal rhetoric versus the actions and words directed at non-members. The group’s coherence and unity has formed the basis for its existence and has served to protect it against outsiders, whether foreign powers or fellow Yemenis. Even now, while governing in Sana’a and controlling the majority of Yemen’s population, the actions of the group remain influenced by the feeling that there always lurks a threat to the movement’s existence.

The full commentary by Sana’a Center Non-Resident Fellow Maysaa Shuja al-Deen can be read here.

Economic Developments

Another Stage-Managed Fuel Crisis in Northern Yemen

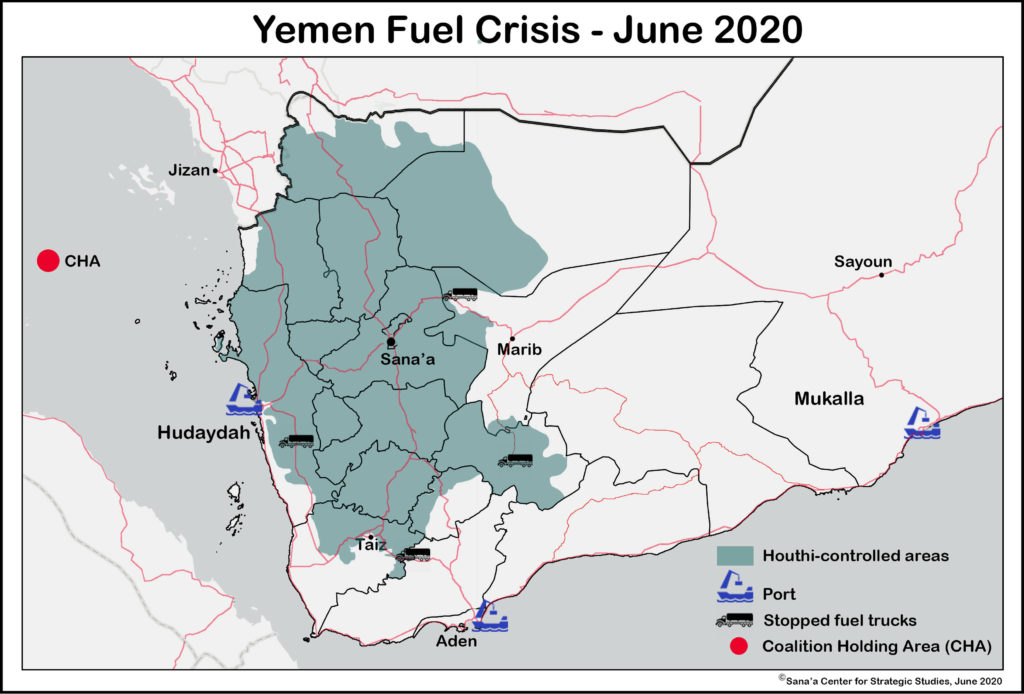

The images are familiar by now: Yemenis in Houthi-controlled territory queue at fuel stations, amid announced shortages. Meanwhile, fuel tankers build up in the Coalition Holding Area (CHA), located in international waters in the Red Sea offshore of Jizan, Saudi Arabia. The number of ships awaiting approval from the government and the Saudi-led coalition to proceed to Houthi-controlled Hudaydah port reaches the proportions of a small flotilla. Combined, these images would seem to tell a simple and compelling story: the Saudi-led coalition and Yemeni government are preventing fuel from entering Hudaydah to spite the Houthis, and ordinary Yemenis are paying the cost.

Yet the reality is much murkier. The truth is that the government and the Houthis are both guilty of participating in a self-interested tug of war to control fuel imports through Hudaydah, with little concern for the human cost of the disruption. This time around the Yemeni government, supported by the coalition, suspended approvals for fuel imports to dock and unload at Hudaydah throughout June. The Houthis, meanwhile, exploited the halt in fuel imports for political propaganda purposes and economic gain. By framing the fuel crisis as a symptom of foreign aggression that is exacerbating an already dire humanitarian situation, the group attempted to absolve itself of any responsibility while cynically controlling the supply of fuel to market, driving up prices, and, by extension, Houthi revenues.

Origins of the Latest Fuel Standoff

Currently, all fuel import shipments headed to Houthi-controlled Hudaydah port must pass through the United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism (UNVIM) in Djibouti. Once cleared, they then proceed to the CHA for a security check by the Saudi-led coalition. Before receiving authorization to proceed to Hudaydah port, vessels must receive final approval from the government’s Technical Office of the Supreme Economic Council, which checks that importers have submitted the necessary paperwork, in accordance with government fuel import regulations. In June, however, the Yemeni government suspended permission for fuel tankers to exit the CHA and dock at Hudaydah port. The last fuel shipment to arrive at the port prior to this was aboard the Alejandrina on May 31, carrying 8,400 metric tons (MT) of fuel oil. As of June 30, a total of 20 vessels carrying a combined 500,000 MT of fuel were in the CHA.[29]

The Yemeni government made the move after becoming suspicious that the Houthis had withdrawn up to 45 billion Yemeni rials (YR) from a ‘special account’ at the Central Bank of Yemen’s (CBY) Hudaydah branch, and misappropriated the funds by channeling them to the group’s war effort.[30] The account contained months of fuel import taxes and customs fees which, per an agreement that the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen (OSESGY) brokered in November 2019 between the Houthis and the government, would be earmarked to pay public sector employees in Houthi-controlled areas.[31] The mechanism was essentially a scaled-down version of an unrealized aspect of the Stockholm Agreement, in which the parties had agreed that revenues from Hudaydah, Saleef and Ras Issa ports would be deposited at CBY Hudaydah and used toward the payment of public sector salaries.[32]

The November fuel import mechanism was intended to prevent future disruptions to fuel imports entering through Hudaydah, which then get distributed in Houthi-controlled territories, following multiple fuel crises in 2019.[33] In March and April last year, there was a significant buildup of vessels in the CHA and a disruption to the domestic fuel market after the Houthis allegedly urged importers not to comply with the government’s Decree 75, which outlined regulations that must be met for obtaining permission to import fuel into Yemen. Traders who wished to import via Hudaydah port already had to obtain authorization from the Houthi-run Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) and agree to hand over the fuel to the YPC, the sole authorized fuel distributor in Houthi-controlled territory. As a sweetener, the Houthis offered to cover demurrage costs for vessels delayed from docking at the port, according to several fuel traders who spoke with the Sana’a Center at the time. The same standoff played out again in September last year, this time in reaction to the government’s Decree 49, which obligated all fuel importers to pay fuel import taxes and customs to the government in order to import fuel into Yemen, in addition to allowing for fuel quality control checks.

Funds in the CBY Hudaydah special account were supposed to be left untouched until the two sides agreed upon the list of public sector employees to be paid and which side would make up any difference in the amount needed to cover the salary payments. On April 16, the Houthi-run Supreme Economic Committee issued a statement saying that the OSESGY mechanism had expired and that it would use revenues accumulated up until March 31 to unilaterally start paying an undisclosed number of public sector employees in Houthi-controlled territories half salaries, though as of the end of June there was little indication that these payments had been made.[34]

Evidence that the funds were withdrawn and used for Houthi military campaigns is circumstantial. According to government officials, per the terms of the November 2019 agreement, the Houthis agreed to provide regular bank statements to OSESGY, which would then be conveyed to the Yemeni government, proving that the fuel and tax customs revenues remained in the CBY Hudaydah special account.[35] Government officials told the Sana’a Center that they have not seen any bank statements since early February, speculating that the Houthis withdrew the funds to help finance the group’s military campaign and the territorial gains made in 2020.[36]

OSESGY has tried to kickstart talks over a reconfigured version of the fuel import mechanism but the government has been reluctant to enter discussions until the Houthis confirm or return the YR45 billion to the special account.[37] Government officials also told the Sana’a Center that it may again attempt to implement Decree 49, requiring fuel import taxes and customs fees be paid directly to the government rather than deposited in the special account at CBY Hudaydah, with the revenue to then be used to pay public sector employees in Houthi-controlled territory.[38] The government attempted a similar move in August last year, leading to a standoff the following month in which the government eventually backed down.

It is unclear how the same approach from the government would prove any more successful now. Importers will still need authorization from the Houthi-run YPC to enter and unload at Hudaydah port, and the Houthi authorities having demonstrated their willingness to hold up fuel deliveries and risk shortages to thwart the Yemeni government’s attempts to regulate fuel imports. The YPC’s leverage is rooted in the fact that Houthi-controlled territory, where the majority of Yemen’s population lives, represents the country’s biggest domestic fuel market where the most profit can be made.

While suspending imports through Hudaydah in June 2020, the government granted approval for fuel traders to import fuel via Mukalla instead. From Mukalla port, the fuel is trucked overland to Houthi-controlled territory, a substitute trade and supply route used during past disruptions to fuel imports via Hudaydah. The government also sanctioned additional fuel imports via Aden port.

Never Let a Good Crisis Go to Waste

In the run-up to and immediately after the arrival of the last fuel shipment to Hudaydah in May, the Houthis started to sound the alarm on acute fuel shortages in their areas.[39] They warned that the suspension of import activity and accompanying fuel shortages harmed the group’s ability to combat the spread of COVID-19 in Yemen. In a June 6 letter to United Nations Resident Coordinator for Yemen Lise Grande, the Houthis argued that blocking fuel tankers from entering Hudaydah had a considerable negative impact on the humanitarian situation in Yemen, with the lack of fuel directly affecting hospitals, and health, hygiene and water sectors in general. This argument was echoed in a Houthi-run YPC circular on June 9.[40]

Houthi authorities’ statements on the ramifications of acute shortages are worrying, given the scale of Yemen’s humanitarian and economic crises. External actors like the UN and international humanitarian organizations have a duty of care that shapes a collective effort to protect the population at large as much as possible. Prolonged fuel shortages in northern Yemen have significant humanitarian implications, including on the implementation of humanitarian operations and the transportation of food and water, given how fuel prices are a major contributing factor behind the rise in food prices during the conflict.[41]

During June, long lines formed outside fuel stations in Houthi-controlled territories.[42] While the image of vehicles queuing up in Houthi territories implies one story, import data tells a different one, bringing into question the speed at which the fuel crisis escalated. The temporary suspension of fuel imports into Hudaydah on a number of occasions aside, fuel has continued to flow fairly consistently through the port.[43] Over the 12-month-period from June 2019 until May 2020, fuel imports into Hudaydah averaged 195,000 MT.[44] In January and February, imports amounted to 170,000 and 188,000 MT, respectively, with imports then jumping in March, April and May, to an estimated 237,000, 228,000 and 190,000 MT of fuel, respectively.[45] The March 2020 figure represented a record monthly high arriving at Hudaydah port since the conflict began.[46] This suggests that there may have been a surplus of fuel created in Houthi-controlled areas before the group issued the first shortage warnings in June.

The high fuel import levels in March and April coincided with a drop in global prices.[47] March prices fell further in April, with Brent Crude and WTI Crude plummeting to $26 and $11 dollars per barrel respectively.[48] According to Yemeni fuel traders, the time between an importer securing a fuel shipment from the United Arab Emirates, where a significant amount of fuel entering Hudaydah (and Yemen as a whole) comes from, and the vessel arriving at Hudaydah port is typically between 15 and 30 days, with the longer wait time often due to bureaucratic delays.[49] Given this timeline, fuel arriving in late March through May was likely bought on the cheap, with the Houthi-run YPC likely banking on a windfall.

This bet looked to have backfired, however, as the drop in global fuel prices coincided with a drop in global demand.[50] In Yemen, although incredibly difficult to accurately gauge, indicators suggest that demand also notably decreased from March onwards, a view shared by fuel traders who spoke with the Sana’a Center.[51] This was likely linked to decreased mobility among sections of the population fearful of contracting COVID-19 as well as the decline in remittance flows from migrant workers in neighboring countries, namely Saudi Arabia, which has forced Yemenis to deal with reduced incomes and cut back on spending.[52]

With a surge in fuel imports being met with a drop in demand, the Houthi-run YPC likely inadvertently clogged its own distribution pipeline. To avoid losing money as a result of the situation, the Houthis needed an increase in fuel prices.

Fuel Rationing and Higher Prices Leads to More Revenues for the Houthis

The government’s decision to suspend fuel imports appears to have thrown the Houthis a lifeline on their bet on importing cheap fuel, allowing the group to create the public perception of shortages and justify fuel rationing, in turn increasing market prices and allowing the group to recoup more revenues. The Houthi-run YPC instituted a quota system on June 10, with strict time restrictions dictating what times citizens can queue up and purchase up to 40 liters of fuel based on their vehicle registration number, creating a sense of urgency and scarcity.[53] The system was brought in before there were more obvious signs to suggest increased shortages. Three-day long queues were reported in Hudaydah during the third week of June, with the price of fuel at YR17,000 per 20 liters, compared to YR5,000 at the end of May.[54] The fuel price hikes that occurred in Houthi-controlled territories parallel to the buildup of vessels in the CHA also presumably helped the Houthi-run YPC to cover rising demurrage costs.

Evidence for the Houthi objective of limiting the overall amount of fuel available for purchase is also bolstered by the fact that fuel trucks were being denied entry into Houthi-controlled territory. During a June 20 televised telephone interview with Houthi-run YPC spokesperson Ameen al-Shubaiti, Yemeni journalist Abdulhafidh Mougeb asked Al-Shubaiti about why the YPC was restricting the movement of fuel trucks. Mougeb cited up to 60 trucks held in Al-Jawf, 1oo trucks in Affar, Al-Bayda, 50 trucks in Taiz and 50 trucks in Hudaydah. Using the reported figures that Moujeb presented to the Houthi-run YPC spokesperson, the 260 trucks would be carrying more than 50,000 barrels of fuel. On June 26, an estimated 44 fuel trucks were shown in a video circulated on social media idling outside the group’s territory in an area close to the borders between Al-Jawf, Marib and Sana’a governorates.[55] Per local sources the Sana’a Center spoke with, the trucks in Taiz were stopped near Al-Rahidah. In Hudaydah, trucks were being forced to idle near Houthi-held Bayt al-Faqih.[56]

On June 22, the government accused the Houthis of denying more than 150 fuel trucks entry into Houthi-controlled territories and threatening truck drivers and fuel traders.[57] It also denounced such actions as a clear illustration of the Houthis’ rejection of government attempts to lessen the impact of the disruption to Hudaydah fuel imports on the broader population.[58]

While it is notable that the Houthis did not precipitate this current standoff over fuel imports, their actions appear to be taken from a playbook they developed during past episodes: shortages are accompanied by price hikes and well-coordinated advocacy campaigns aimed at the UN and other international actors.[59]

During the September 2019 standoff, the price of fuel in Sana’a climbed to YR20,000 per 20 liters from YR7,300 the previous month, a 239 percent increase.[60] The four preceding months saw a spike in fuel import activity, with 800,000 MT coming in via Hudaydah, compared to 630,000 MT during the first four months of 2019.[61] The import data raises the possibility that the Houthis stockpiled fuel in anticipation for a planned disruption. The supply of Marib Light crude produced at Block-18 in Marib and refined locally is another factor that helps the Houthis to mitigate the impact of any disruption to Hudaydah fuel imports.

When prices went up in September 2019 during the onset of the standoff, Houthi authorities increasingly lobbied UN agencies, INGOs and humanitarian organizations to put pressure on the government and the Saudi-led coalition to allow fuel to enter Hudaydah, with the larger objective likely being to get the government to back down from implementing Decree 75 and Decree 49.[62] The strategy paid off. At the beginning of October 2019, the government and the coalition issued a waiver to a number of vessels that were allowed to proceed from the CHA to Hudaydah without having fulfilled the decree requirements.[63] OSESGY mediation efforts also paved the way for the Hudaydah fuel import mechanism that was agreed in November, a catalyst of the current standoff.

Without Accountability, the Next Fuel Crisis Awaits

The ongoing saga over fuel imports in Yemen represents one front in the warring parties’ reckless economic warfare, which has had an immensely destabilizing effect on the country’s economy and served to exacerbate the humanitarian situation.

The government’s Decree 75 and Decree 49, while ostensibly fuel import regulations, are in the current context weaponized in support of the government’s greater war aims. The Houthi authorities’ response has similarly arisen to protect financial and political dimensions of the group’s wider military pursuits. The mandate of UN agencies, INGOs and aid organizations prioritizes immediate humanitarian need for fuel, but the lobbying of the Yemeni government and the Saudi-led coalition to release fuel tankers held in the CHO has essentially aided the Houthi side in the fuel standoff.

At the same time, international organizations have not called out the Houthi authorities for the latter’s role in stage managing and profiteering from fuel crises in northern areas. According to one fuel trader who spoke with the Sana’a Center, the Houthis have warned importers against sailing their tankers out of the CHA or seeking to break their contracts with the YPC and sell the fuel elsewhere. The Houthi authorities backed up these warnings with threats to deny importers future permission to distribute fuel in Yemen’s northern areas, the country’s most lucrative market.[64]

The longer such standoffs persist and are framed as the cause of a fuel crisis in Houthi-control areas, the higher the likelihood the UN and international pressure will again come to bear on the Yemeni government and the coalition to stand down, again undermining the government’s attempts to assert authority over fuel imports. This appears to be playing out again.

On July 2, the Technical Office of the Supreme Economic Council announced that it would award import licenses to four shipments carrying a total of 92,000 MT tons of various fuels to Hudaydah: one carrying 29,000 MT of petrol, one with 28,000 MT of diesel, another carrying 27,000 MT of mazout, and one vessel carrying 8,000 MT of liquified petroleum gas (LPG).[65] The government authorized the deliveries in response to a request made by the UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths, who met with government officials in Riyadh on June 30.[66] Thirteen out of the 20 vessels idling during June, carrying a combined total of 338,000 MT, had submitted fuel import applications to the OSESGY in June to be passed on for approval to the government-run Technical Office. The four vessels that the government authorized to proceed to Hudaydah Port were among the applications submitted.

While a deescalation of the standoff is a positive outcome for Yemenis at large, a resolution without accountability placed on both sides for their roles in the disruption and the stage-managed fuel shortage almost certainly ensures that Yemen’s next fuel crisis is just around the corner.

Other Economic Developments:

Houthis Institute Tax to Benefit Group’s Leaders and Loyalists

A controversial new decree by Houthi authorities in Sana’a channels tax revenues to a small segment of loyalists, a move critics have decried as discriminatory. On April 29, President of the Houthi-run Supreme Political Council Mehdi al-Mashat signed an executive bylaw that imposes a 20 percent tax on all economic activity involving natural resources, which is anticipated to target most prominently the country’s oil, gas and fishing industries.[67] However, Yemeni outlet Al-Masdar reported that the group had been informally imposing the levy for at least five months, citing its use against sand and gravel crushers, water companies and even chicken farms.[68]

Houthi authorities characterized the new regulations as an expansion of the 1999 Zakat law, the Islamic religious obligation that is intended as charitable almsgiving to underprivileged groups. Based on the new interpretation, revenues from the tax would go directly to the Ahl al-Bayt, descendants of the Prophet Mohammed, which includes the Al-Houthi family and Yemen’s Hashemites, made up largely of Houthi loyalists. The move harkens back to the pre-republic Yemeni Imamate, where the ruling dynasty and other Hashemite families enjoyed special privileges and were considered above the rest of society. It also fits with Houthi ideology, which advocates the Ahl al-Bayt have a divine right to rule.[69]

The new Zakat regulations drew fierce criticism on social media and from the Yemeni government. Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed accused the Houthis of fracturing Yemeni society and rejecting the values of equal citizenship enshrined the republic’s constitution, saying in a tweet that the new law was based on “hereditary discrimination and racism.”[70]

STC Seizes Newly-Printed Yemeni Rials

The STC-run Supreme Economic Committee announced June 13 that it would prevent the government-run Aden central bank from feeding any newly-printed banknotes into the market, in view of protecting the value of the Yemeni rial in Aden against further depreciation.[71] On the same day, STC-allied forces intercepted seven containers that had an estimated YR60 billion newly-printed banknotes inside, the equivalent of almost US$80 million.[72] The STC’s actions came as part of ongoing efforts to manage the local economy in Aden following the declaration of self-rule in late April 2020.

According to one Aden-based banking official, the newly-printed banknotes that the STC intercepted did not have a serial number on them and so would not have been fed immediately onto the market.[73] The normal practice would be for the notes to be stored at the Aden central bank and then when the bank is ready to issue the new notes a serial number is added. The timing of the STC’s actions were also significant as they seemed to occur during a period in which the Saudi-led mediation efforts between the STC and the government had been temporarily suspended.

On June 30, Saudi-led coalition forces intercepted a separate batch of newly-printed Yemeni rial banknotes at Mukalla port before transporting the notes to the local central bank branch in the city.[74] According to one government official that the Sana’a Center spoke with, the undisclosed amount of Yemeni rial banknotes is currently under the watchful eye of coalition forces at the central bank in Mukalla.[75]

For more information on the economic implications of the STC’s latest powerplay in Aden and what it means for the government-run Aden central bank, see: Yemen Economic Bulletin: STC’s Aden Takeover Cripples Central Bank and Fragments Public Finances.[76]

Yemenis in Sana’a were in the clutches of both a fuel crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic last month (pictured here on June 15, 2020) // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

The COVID-19 Pandemic

As the Virus Advances, Yemenis Adjust to New Realities

COVID-19 continued to spread rapidly across Yemen at the end of June, UNOCHA reported, although a severe lack of testing and under-reporting meant figures for confirmed cases and deaths remained low.[77] By the end of June, just 3,508 COVID-19 tests had been carried out in Yemen, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported, but this figure did not include positive test results from Houthi-controlled areas as Houthi authorities only report negative test results.[78] The armed Houthi movement is not disclosing the number of cases or deaths in territory it controls. The internationally recognized Yemeni government reported 818 cases and 173 deaths in areas it nominally controls in June.[79] By July 5, a total of 1,252 cases of COVID-19 and 338 deaths had been announced in Yemen, the WHO reported.[80]

Modeling published in June by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Studies projected that the unmitigated spread of COVID-19 in Yemen could lead to 7.7 million to 11 million symptomatic cases and 58,000 to 84,000 deaths after six months.[81] The study projected demand for critical care would peak roughly four months from the start of transmission, when between 24,000 and 44,000 people would require critical care. At the end of June, Yemen had just 710 intensive care beds, 380 ventilators and 25 operational isolation units.[82]

The Sana’a Center spoke in June with Yemenis from across the country about what it is like to live through a pandemic in a war-torn country with a shattered health system. Their responses have been edited for clarity.

Athar Ali Mohammed Yahya is a civil society leader in Aden and director of planning and development at Alf Ba Civilization and Coexistence Foundation. Deaths in Aden surged in May due to COVID-19 and other infectious diseases that spread in the wake of heavy flooding in the city.[83] Several hospitals, unprepared to deal with the pandemic, simply closed as cemeteries overflowed. Yahya said that life in Aden at that time was especially grim, but described a city learning to live with a new threat.

Personally, look, in May, we went through very difficult circumstances in Aden, and I was feeling down because all we heard of during this phase, which was also during Ramadan, was about deaths: ‘our neighbor died,’ ‘a colleague died,’ ‘a relative died,’ ‘one of my parents died,’ and so forth. There was death every day. They were tragic circumstances, and we felt that everyone abandoned us during that period: the warring political factions, the Southern Transitional Council, [President] Hadi’s government, they were in conflict and they abandoned everything.

Now, people’s awareness is better, and hygiene too. There are very large campaigns in Aden that have greatly contributed to decreasing deaths and infections. As for wearing the facemask, people before were not convinced there is COVID-19 in Aden. But now, people understand that it is here and that wearing the facemask lowers infection. This does not mean markets and places are not crowded, but there is awareness, people are even eating more healthily. They understand it is important to strengthen immunity. I now have hope, and I believe we have overcome the crisis, but of course by staying home as much as possible and abiding by precautionary measures.

As you know, working from home is a tragedy in a city where there isn’t strong electricity or internet. This always affects work as it takes longer to finish work from home. On a personal level, there has been a positive and negative impact. What has been positive is that I see my family more, and I’ve had time to read more than before. What has been negative is that I realized I was not someone who likes to stay at home, and I have been at home for so long now.

In Yemen’s other major southern port city Mukalla, in Hadramawt, English Literature professor Khaled Balkhasher said life started to return to normal in June. Yemen’s first announced case of coronavirus was reported in Al-Shihr port in Hadramawt on April 10, leading to curfews and movement restrictions in the governorate. On June 10, Hadramawt governor Faraj al-Bahsani issued a decree banning non-Hadramis from entering the governorate as part of efforts to combat the spread of coronavirus. To enforce the measure, military posts were established at the borders with Shabwa and Marib governorates.[84] As of June 27, Hadramawt had confirmed 310 cases and 122 deaths, the highest numbers in Yemen, although this may be in part attributable to its more proactive local authorities.[85] Balkhasher, who teaches at Hadramawt University, described a city emerging from lockdown.

“Mukalla is a city where people gathered in cafes and other places. People were deprived of their lifestyle… Besides, the hot weather and humidity made life indoors unbearable. The power cuts that last 12 to 16 hours added salt to the wound.

But, now it has been okay. I can move in the city and practice my hobbies from dawn until 8pm. Things are back to normal, about 70 percent of the way. Starting about two weeks ago, cafes started opening again until 8pm. People have begun to live almost normally… The deaths are mostly due to other diseases, like dengue fever.

Still, at the beginning, this felt more difficult than anything we have faced in Mukalla in recent years. I lost some colleagues and friends. I felt for a moment that we could not face the pandemic with our very poor health system.

At the university, whether we will do online classes or resume classes indoors depends on the instructions from the Ministry of Higher Education. While there is an option to give lectures via Zoom, that is difficult because of our weak internet. Probably, we will either resume classes with social distancing or double the marks of the first round of exams to just end the academic year after classes were suspended in April.

In Yemen’s capital, Sana’a, Houthi authorities reported four cases of COVID-19 in May; they have concealed all cases and deaths since then. Médecins Sans Frontières, which is supporting the main treatment center for COVID-19 in Sana’a, said in June that the 15-bed intensive care unit was consistently full and that the team there had witnessed a high rate of deaths.[86] Dr. Nabil, who works at a public hospital in Sana’a, said medical staff were struggling to treat patients due to inadequate funds and resources. Yemen is facing an aid funding crisis and donations have fallen in part due to concerns over Houthi interference in aid distribution.[87] Dr. Nabil said his hospital had received no support, but that staff continued to work out of duty toward their patients. The Sana’a Center is using a pseudonym for this doctor due to Houthi authorities’ intimidation of doctors who discuss COVID-19 publicly.

“When we met with the [Houthi health] minister after Eid, we were told that there is no support from any organization [for our hospital], and that we were alone in dealing with this situation. In this period, [some hospital staff] have worked for free, without salaries. The hospital must function using only its own revenues. Imagine, there is no support from any organization or even from the ministry. There are not any ventilators in the intensive care unit, so work is really quite difficult. Most of the challenges we experience when facing a grave situation like coronavirus are because we have very little capacity to do anything… Despite all the difficulties we faced because of the war, with coronavirus it is more difficult because of the cuts in aid.

And yet, there is a group of hospital employees who continue to work because they swore an oath. Despite these harsh conditions, they will work and there is nothing that will stand in their way from doing so. They were trained how to treat coronavirus cases. Their spirits remain strong, even without any material support. For them, it’s not possible to abandon the Yemeni people, and so, they give their all.

At Al-Thawrah Hospital in Taiz, a city that has experienced the brunt of the war between Houthi forces and fighters loyal to the internationally recognized government, Dr. Abdulrahim al-Samie spoke of the challenges of keeping employee morale lifted. Yemen suffers from a shortage of trained medical staff, and doctors have reported a high fatality rate among medics dealing with the pandemic.[88] Dr. Al-Samie said spreading hope helped to galvanize his team, whether facing a war or a pandemic.

“For me, in comparing the challenges brought by the war with those brought by the coronavirus pandemic, the separation between these challenges is a small margin. It can be said, in the end, that both are war. There is an enemy and there are those who defend against an enemy. The big difference is that coronavirus is an unknown and invisible enemy. It’s possible for it to attack at any time, and so the daily challenges against an invisible enemy almost bring more mental and physical pressure than war, and that’s in addition to the daily grind of war.

Of course, there is hope. I am an optimistic person. I find hope through patience, through persevering, through expecting the best out of the future… especially as I am responsible for maintaining morale so that those under my administration stick together. I always try to give hope to those around me in order to preserve social cohesion. I try to use human and financial resources to invest what is available as much as possible. The challenges do not go away easily, and sometimes they accumulate, especially in this time of epidemic. Coronavirus accumulates and breeds, and each challenge gives birth to another, but our experience during the past six years made us insist on life. Insisting on life generates hope for tomorrow.

Environmental Developments

In Focus: How Weak Urban Planning, Climate Change and War are Magnifying the Impacts of Floods and Natural Disasters

This year, Yemen experienced a series of weather shocks as flash floods swept through 15 governorates across Yemen between March 24 and June 6, affecting some areas multiple times. Considering that 80 percent of the Yemeni population is in need of some form of humanitarian assistance and more than 3.6 million people are internally displaced,[89] while public services and infrastructure have been laid bare during five long years of war, swathes of Yemen’s population are vulnerable to the immediate and long-term impact of these floods. This comes in the midst of a global pandemic, a continuing war and cuts in international aid to Yemen.[90]

The long-term impact of floods and natural disasters on the various sectors and overall GDP in Yemen are little understood, but some studies conducted following the 2008 Hadramawt floods indicate a lingering effect of such disasters on food security and household income. While agriculture is the sector worst hit by floods, others such as the service sector and food processing industries feel the shockwaves of such disasters.[91] According to the Climate Investment Fund, the 2008 floods inflicted damage amounting to 6 percent of GDP.[92]

Although rainfall in Yemen may be intense during its short spring and summer seasons, particularly in the Western highlands, an alarming change in weather patterns in the past decade has resulted in a higher frequency of flash floods and tropical cyclones, a novel weather phenomenon in Yemen. These are recurring in normally dry areas that received 50 mm of rainfall annually such as Hadramawt, Al-Mahra, Shabwa and Marib. In 2008, Hadramawt sustained long-term damage from floods that is still felt until today, according to Omar Shehab, the Director General of the Environmental Protection Authority in Hadramawt.[93] In 2015, the first tropical cyclone recorded since modern records began in the 1940s hit eastern governorates and the Socotra archipelago; two other cyclones occurred in 2018.

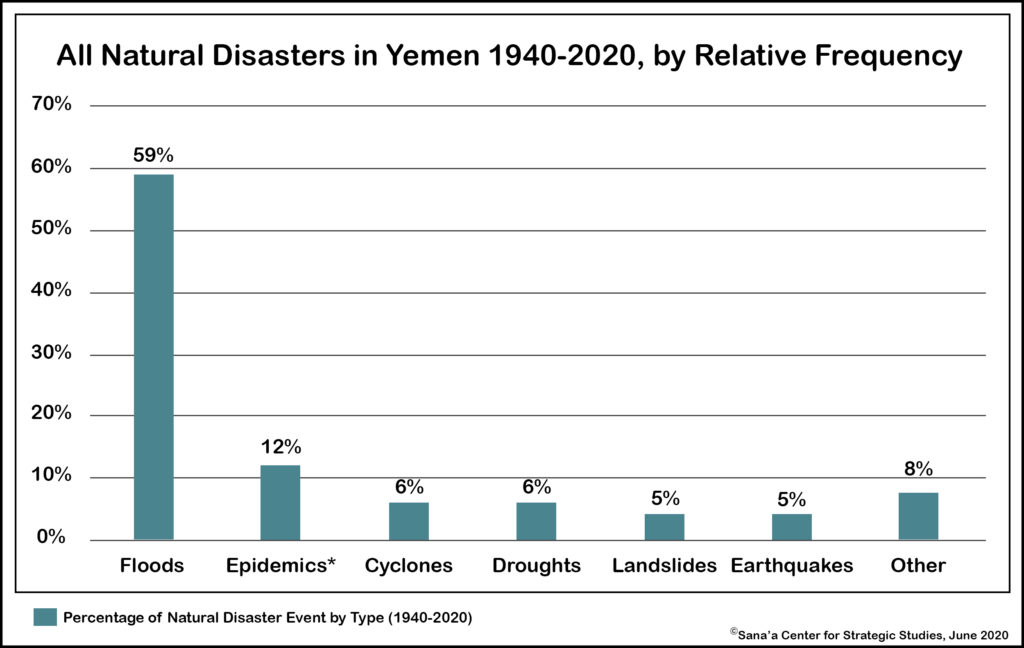

Extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and more intense, bringing Yemen face-to-face with a looming climate change emergency. Yemen is ranked 167 among 181 countries on the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) index in 2017, which measures countries’ vulnerability and readiness to face climate change.[94] Floods constitute the highest recurring natural disaster in Yemen; 39 floods happened between 1972 and 2020, making it an almost yearly occurrence and sometimes multiple floods occurred in a single year.[95]

Source data: EM-DAT, CRED / UCLouvain, Brussels, Belgium, www.emdat.be (D. Guha-Sapir), 2020-06-15; *Excluding COVID-19

Between March and June 2020, 150,000 people were affected by the floods, including 64,000 internally displaced people, and a further 7,000 became displaced within this period as a direct result of the floods.[96] According to a UN source, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to comment publicly, a network of local NGOs was mobilized including many volunteers to assess the damage and provide hygiene kits, food baskets and make-shift shelters to those who lost their homes. This was significantly hampered in April and June due to COVID-19 risks that restricted movement of humanitarian staff and aid. However, according to the UN source, “the biggest challenge is having a very weak national coordination body in the interim capital, Aden, that is absorbed in a political tit-for-tat.”

In ideal circumstances, the responsibility for rescue operations and disaster response coordination lies with the Civil Defense Authority, according to Yemen’s Law 24 of 1997 on the Civil Defense.[97] Fuad Ali, a UNDP Deputy Team Leader in the Economic Resilience and Recovery Team, said that civil defense received capacity building and support to respond to disasters prior to the war.[98] However, a source in the Civil Defense Authority in Sana’a said that their current work has been reduced to firefighting and basic rescue operations. The civil defense official explained that the agency does not have the capacity or resources for the wide range of responsibilities stipulated in the law or set in its disaster response plan.[99]

In Aden, the Civil Defense Authority has been almost stripped bare. According to the head of the Aden Civil Defense, Major General Mohammed Al-Shab’an, their offices were looted during the Houthi incursion in 2015. They now have no presence outside of Aden, are left with only a few firefighting vehicles and receive funds, often late, for operational costs that barely cover maintenance of vehicles and staff salaries. Al-Shab’an said no plan was in place to respond to the flooding disaster and there were no designated evacuation locations or capacity to evacuate people. “We tried our best given the limited resources available to us, such as driving our firefighting vehicles around the city to make public announcements for the residents to take the necessary precautions,” Al-Shab’an said, adding that the floods in Aden were especially devastating because of unplanned urban development as buildings blocked and redirected the path of flood waters. Water flow was further obstructed by security roadblocks that riddle the city, especially around high-value buildings such as the Central Bank of Yemen.[100]

Interviews with Aden residents convey some of what people experienced during these floods. Zahra’a Ali, 22, a sociology student and resident of Crater, one of the districts in Aden badly affected by the floods, described how the flood water picked up large rocks and debris as it carved its path through the mountains, becoming thick with garbage and mixing with an overflowing sewage system. In some areas, entrances to homes were blocked by a thick layer of silt carried by floodwater from the mountains, she said. The Al-Khesaf neighborhood, which houses marginalized communities in fragile tin houses, was essentially washed away. Crater’s old system for rainwater drainage known as manahel was ineffective as newly constructed buildings blocked them and flood water that became trapped in neighborhoods quickly turned into foul swamp water.[101]

According to another resident of Crater, Ayah al-Ebbi, 23, a student of laboratory sciences involved in community work, the flood response came primarily from youth activists, who appealed to local philanthropists to cover the high costs of vacuum trucks that drain water from residential areas. Al-Ebbi currently hosts her relatives who fled their home in April after losing all their furniture in the floods. She said that some local NGOs came to assess the damage and distribute hygiene kits and, while she praised local initiatives that swiftly mobilized in response to the calamity, she said the scale of the disaster required an official and coordinated response from the state. Nevertheless, Al-Ebbi said many residents were better prepared when floods occurred again on April 21, having sealed their homes, and immediately drained the water as it flowed.[102]

While residents spoke of some district heads responding quickly with whatever means possible, a video circulating on social media two days after the second round of floods showed the acting governor of Aden, Ahmed Salem Rabi’, followed by residents in Crater demanding water and electricity and hurling obscenities at him.[103]

Al-Mahra is another governorate that has suffered from floods and cyclones in recent years. “People of Al-Mahra remember with horror the cyclone of 2018,” said Noor Makki, 28, a resident of governorate capital Al-Ghaydah who works at the Fisheries Authority, “so when meteorological warnings announced an atmospheric depression, we were on high alert and many people took shelter in the mountains.” Makki said that while the rains were not as severe as they had initially anticipated, they did affect certain areas prone to flooding where internally displaced people (IDPs) and newcomers had settled.[104] A similar situation devastated 3,500 IDP shelters in Marib governorate,[105] where the largest displacement site, Al-Jufaina, is located.[106] The Shelter Cluster, the inter-agency coordination body co-chaired by UNHCR and IOM and responsible for coordinating IDP shelter management and aid distribution, was unresponsive to multiple Sana’a Center requests for comment.

Building on flood courses is also a problem in Hadramawt, according to Dr. Khaled Bawahedi, an associate professor at the Faculty of Environmental and Marine Sciences in Hadramawt University. “The local government continues to tolerate the construction of houses on flood courses and valleys, with complete disregard to the risks this poses to the population — often to IDPs and poor communities. During this round of floods and also during previous floods, some communities were deprived of clean water – this is what happened in Al-Hajr, one of most badly hit areas in Hadramawt,” he said. Bawahedi sees a clear link between these weather shocks and climate change, but said higher education institutions’ resources to research and share knowledge on adaptation and mitigation are limited and official support is lacking for this type of work.[107] Omar Shehab said the Environmental Protection Authority he leads in Hadramawt was shut down from 2013-2017, and that funding for research and even basic field data collection is non-existent.[108]

In discussions with people from some of the affected governorates, one gets the impression that each operates in isolation; there is no sense that climate change-related disasters cross not only governorate lines but national and international borders. According to Anwar No’man, an environmental scientist who has been working on climate change in Yemen since 1996, Yemen is party to the main international environmental treaties and has taken some steps in adaptation and mitigation. In 2009 it developed a National Adaptation Program of Action and continued to submit periodic reports to the parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the latest of which was in June 2018. However, development and climate change projects were sidelined during the war as donors shifted their focus and funds to short-term humanitarian aid. “Climate change action is an emergency that requires long-term commitment,” No’man said. When asked about whether communities are aware of climate change, he explained, “Farmers are becoming aware of a shift in seasons and rain pattern disruptions. They might not be aware of concepts such as climate change and global warming, but they understand from first-hand experience that nature is changing and it’s causing their crops to fail.[109]

This year’s floods, an emergency requiring an immediate response on par with humanitarian emergencies caused by the war, are also part of a global emergency that requires a coordinated long-term commitment. There is no sign that the intensity of rains and cyclones will be abated; on the contrary, they are expected to become more extreme. Communities and local governments require the tools and knowledge to adapt to such disasters and to understand the risks of redirecting rainwater without proper planning. The frequency of floods in Yemen should make flood risk reduction in IDP sites a priority, especially as several IDP sites are situated in high-risk areas.. The risk of floods remains high in Yemen for the upcoming months as the rainy season may stretch until October.

Yasmeen al-Eryani is a non-resident fellow at Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies and a Ph.D candidate in Social Anthropology at Tampere University in Finland, where her research focuses on education practices during armed conflict in Yemen. She tweets @YEryani

FSO Safer: Renewed Warnings of Environmental Catastrophe

Seawater has leaked into the engine compartment of the FSO Safer, according to a report by The Associated Press, renewing focus on the potential environmental disaster posed by the abandoned oil tanker positioned in the Red Sea off the coast of Hudaydah.