On returning from work one evening, my house was unusually quiet. Only my sister was home, and she was packing up a few things. I knew immediately my parents had taken the decision she and I had been resisting for weeks: we were leaving the home I had grown up in. Armed fighters on every street, especially those visible from our second-story windows on the roof of the house next door, made it unwise to stay any longer. It was March 2015, and the war clearly was coming our way.

I packed a few things, some clothes, my passport, university certificates, photographs, and headed through the darkness of a power outage to an empty flat my father had rented a few blocks away in my city of Taiz, the start of my journey as an “internally displaced person” – an IDP in humanitarian agency shorthand, a statistic in Yemen’s war.

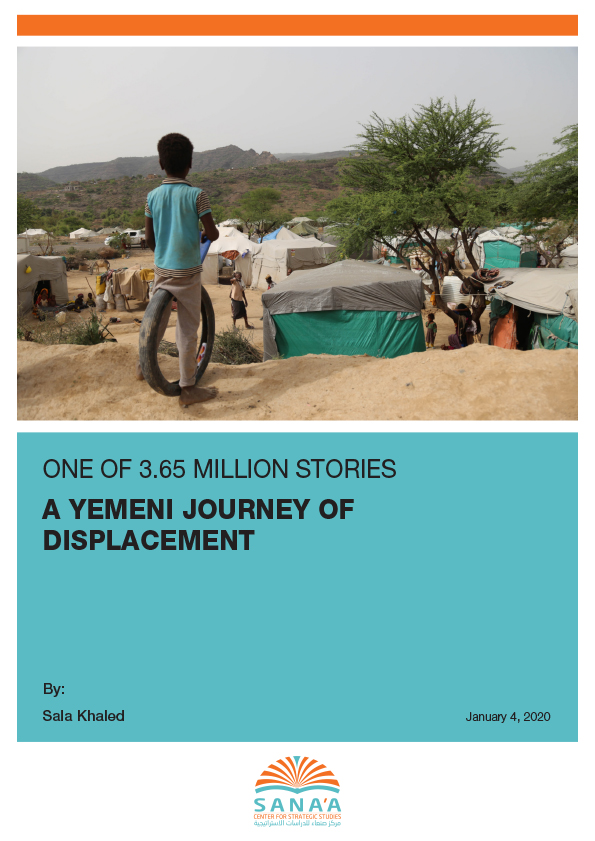

Through nearly five years of conflict, an estimated 3.65 million Yemenis have been displaced.[1] Some, like me and my family, eventually joined the Yemeni diaspora, more than 375,000 people scattered in Ethiopia, Oman, Somalia, Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, Jordan, Egypt, Sudan and elsewhere.[2] But poverty and the sheer difficulty of traveling out of the country has left far more people who are trying to escape active frontlines moving about inside Yemen, renting rooms and flats, moving in with relatives, filling IDP camps and shelters.

Conditions vary as much as individual stories do, but according to a recent report by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, IDPs in rural Yemen tend to have fewer services and work opportunities, and are more reliant on humanitarian aid; those moving to Yemen’s cities generally do so for a better chance at finding work. Many IDPs, especially those from rural areas who owned land, said they hoped to return home; others are working to build new lives in new cities.[3]

My city, Taiz, is planted over a rocky hill 270 kilometers south of Sana’a, the capital. Some streets are like rollercoasters, and walking them is a workout. Prior to the war, Taiz was known for Saber Mountain, a weekend picnic destination overlooking the city of 600,000, and for its salty, smoked cheese that is eaten with sweets and chutney. Now, it is known for its ever-present frontlines and humanitarian crises.

The Saudi- and Emirati-led military coalition’s airstrikes began March 26, 2015, when the coalition entered Yemen’s civil war to dislodge Houthi rebels who had taken over Sana’a and to restore to power the government led by President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi. In those days, the Houthis were focused on Aden, where Hadi had fled. Houthi fighters passed through Taiz on their way to the active fighting in Aden, leaving some armed men behind in a quiet shifting of power in the city. Armed men in the streets became a common sight, but ground-fighting had not yet begun. A vacant house next door to ours had been rented to a new tenant, a local member of the armed Houthi movement. Instead of moving in family, however, the house began to fill with fighters. When coalition airstrikes began in Aden and on the outskirts of Taiz, my parents recognized it was only a matter of time before our new neighbor attracted attention.

On the Move: A Few Blocks isn’t Far Enough to Escape Airstrikes

That first evening in the nearby flat, I couldn’t bear my new lodgings – sparse with no power, mattresses on the floor, bare walls with sheets hung up as curtains over windows. My sister and I went to a nearby cafe, thinking to cheer up with a frappuccino and an hour of internet. The cafe owner welcomed us, but said the generator was out of fuel and shortages meant he couldn’t buy the diesel it needed. We returned to the flat. To pass time, I pulled out a book I’d started weeks earlier, 1919, by the Egyptian novelist Ahmed Mourad, and reading by a rechargeable light, came across a passage that reads: “My friend, as long as we do not die, there remains hope. … One day, we will be very important. … We will free this country from dirt. … We will not die here like dogs.” I still keep a picture of that passage on my phone. I am not one to believe in messages sent by the universe, but at that moment, I wanted to believe I would survive.

I woke up early for work and smelled my mother’s bread cooking in the kitchen, a smell I never particularly liked but now found comforting. With petrol in short supply, the streets were quiet. At my office, a company for exporting Yemeni goods, everyone was frustrated – complaining they couldn’t charge their phones or even iron their work shirts and hijabs. We were told to take a holiday until things got better. They never did. Time moved so slowly that week, and we passed our days inside the flat playing round after round of cards, while outside life had come to a standstill: no electricity, no fuel, no public transport. It was still early in the war, people were afraid to go out, making just quick trips for necessities.

The following week, just before Friday prayers, an explosion shook the neighborhood. I grabbed my hijab and ran to the corridor, where I saw my sister slowly fall against the wall and crumple to the floor in shock. My mother and I helped her stand, and we ran across the street to where my older brother and sister lived with their families. Smoke was rising from the end of the street, the site of a military base located near my old school. Flashbacks to 2011 filled my mind, when Taiz was indiscriminately shelled during fighting between forces loyal to and opposing then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh. But this was an airstrike, a totally new, horrifying experience.

We sat under the stairs, in the basement of my siblings’ building, listening to the explosions while my father stood outside watching airstrikes on the neighborhood. I wanted him to come inside and, at the same time, I wanted us to get outside – I was afraid an airstrike would destroy the building on top of us. My sisters, nieces and sister-in-law were crying; only my youngest niece was grinning, happy we were all sitting together.

Our days went on this way for about two weeks, and each time I heard the plane overhead my hands would go cold and my eyes would widen as I tried to slow my heartbeat and listen for where the airstrike would land. At that time, as a Yemeni, I felt like my existence didn’t matter to anyone except my family. To get past this feeling, I tweeted about the situation, joining in social media campaigns to end the war. “By God, I feel that it’s useless, we waste our energy telling the world ‘enough war’ but it’s never enough to them #Yemen #KefayaWar.” I knew it was hopeless, but it felt better to speak up and, in a way, be heard.

Staying any longer in Taiz became unbearable. We considered three options: Hudaydah, 250 kilometers to the northwest and still safe at that time; the village of our family’s roots on the outskirts of Taiz; or the city of Ibb, 60 kilometers north. Hudaydah was too far, our village wasn’t a good option as we had no house there and services were limited, so we chose Ibb. The following day, we packed our few things in handbags and loaded ourselves into two cars: Me, my parents, my two sisters and sister-in-law, my brother and brother-in-law, and five nieces. I waited until the last moment to get in the car, afraid that if the plane returned I would be trapped inside, unable to run.

War as a Way of Life: When Safety Without Work and Community Feels Worse than War

I prayed we wouldn’t be hit by an airstrike, and within 10 minutes we were outside the city limits and away from the warplanes flying overhead. From there, it was a smooth trip, made early in the war before roadblocks and checkpoints made travel inside Yemen slow and difficult. In Ibb, we chose the first hotel we came across. It was new and big, far from the city center. I shared a room with my sister and, like in Taiz, we spent our days reading and playing cards. There was no hot water or laundry facilities. The hotel generator ran from 6 p.m. until 10 p.m., when we would charge our phones and use the sketchy wi-fi. We ventured outside only rarely, finding cabbage farms and a place to sit and have biscuits and tea until sunset prayers.

After about three weeks, we decided together we would rather take our chances and go back to Taiz than sit, doing nothing, in a hotel. We knew we would not be able to return to our own house, but we had heard the airstrikes had eased. Our family belonged in Taiz, where we hoped we could ride out the war in the rented flat now that the nearby military camp had been destroyed. We returned to a momentarily quiet city, but the battle soon shifted from airstrikes to fighting on the ground between Houthi forces and government troops and their allies. Tank fire seemed so random it was impossible to identify potential targets in order to avoid the shelling. Back in the rental flat, located in a part of the city under Houthi control, we could hear anti-Houthi forces’ shells hitting several streets away. My sister and I pulled our mattresses into the windowless hallway and passed a sleepless night listening to the war outside.

The next morning, our family walked together to check on our house. It was intact, and so was the neighbor’s house, still occupied by fighters. My father sat down on the sofa, leaned his head back and stared at the ceiling. I’d never seen him like this before. Together, we removed a few things and, in less than an hour, left for the last time, my father quietly locking the door behind us.

Making Plans for a New Life, Away from Yemen

It was mid-May, and as I wrote on Twitter at the time, “things were on fire” in Taiz, and my parents decided returning had been a mistake. With no good options, we left again, passing cars that were lined up for a couple kilometers over the mountain waiting for petrol to arrive, and returned to the same hotel in Ibb. Soon after, my parents spotted several armed men in the hotel lobby. They were Houthi fighters meeting up with a senior officer to receive their salaries. We quickly packed up and left to find another hotel away from fighters or their camps. A couple days later, not finding a suitable place for a long stay, my brother called the hotel to ensure the fighters had left, and we returned.

We spent most of our time in our rooms, with only my older brother going out to buy food. We heard distant airstrikes, but there was no active fighting nearby. Several displaced families from Taiz had taken refuge in the hotel. It wasn’t long before a nearby camp came under heavy airstrikes and hotel staff guided us to the basement. About 20 women and children already were downstairs. I asked about their plans; everyone said their stay in Ibb was temporary, to wait for passports to be issued or to prepare to head for the border with Saudi Arabia to stay with family there. Others hoped to return to Taiz. Our plan was still developing.

My mother interrupted, the bombing had stopped and she told my sister and me it was time to leave this hotel. She had been walking around the farms the day before when she heard a rumor the coalition would bomb a camp near the hotel and also the hotel itself, which the woman who shared the rumor said was Houthi-owned. With the first part of the rumor proving true, we no longer felt safe and packed, again, unsure where we were going. As we drove through Ibb, my father settled on Sana’a, where my two other brothers were living. The 13 of us moved into the duplex their families shared. I focused on finding a way for us to leave Yemen, urging my family to make the journey through Al-Tuwal border crossing and into Saudi Arabia.

The area around Al-Tuwal, 275 kilometers northwest of Sana’a, was a frontline area on the Yemeni side of the border. Families still risked the drive, even though many were being turned back along the way by Yemeni fighters. Although Saudi Arabia was allowing Yemenis to enter, it wasn’t long before fighting near the border effectively shut it down. Much farther, more than 500 kilometers northeast of Sana’a, was Al-Wadiah border crossing, which was intended as a commercial border, but many families were using it to cross into Saudi Arabia then fly on to Cairo or Amman. My father rejected these options, however, confident Sana’a International Airport – which had been closed to civilian flights since March 28 – would open soon and having decided we would fly to Jordan.

My father was right, and on May 19 Yemenia airlines announced their flights were resuming from Sana’a airport. The first two flights to Amman were fully booked; we managed to get seats on the third flight, on June 5. Windows in the terminal had been shattered, dust and stray cats were everywhere. Many families arrived well before the flight was scheduled to leave. One woman was seeing off her son, whom she was sending to Canada to finish his studies there; another woman was accompanying her sick child to Amman for medical treatment. Taking off brought with it a sense of relief – everyone just wanted to leave – though the first stop required of all flights departing Sana’a then was Besha airport in Saudi Arabia. There, Saudi security checked the plane and passengers before clearing our departure for Amman. The Saudi- and Emirati-led coalition would force Sana’a airport to close again in August 2016 to commercial traffic. Four years later, flights are still yet to resume.

No Longer an IDP, Resettling in Jordan

Many Yemenis have found a home in Amman, with about 14,700 registered as refugees in Jordan.[4] Actual numbers are higher because many Yemenis with means of support who came to Amman have not sought refugee status or aid, but, like my family, have bought or rented houses and are settling as migrants at least until they feel safe going home. After four years in Amman, I am grateful to be alive and feel privileged to be safe. I miss Taiz from time to time, most often when I visit the old part of Amman; its hills and buildings remind me a lot of my city, but I don’t plan to return anytime soon.

One of the main reasons we initially left our home doesn’t exist anymore. Airstrikes on August 4, 2015 – two months after we left Yemen – destroyed the house next door where the Houthi fighters had lived. Our house was damaged, but is intact. Photos sent to us showed our boundary wall destroyed and windows shattered. Furniture had been damaged, with some strewn in the yard, presumably by vandals; dust and debris were everywhere, and there clearly had been a failed attempt at dislodging and stealing our heavy generator, now stripped of its battery.

Settling in to Amman wasn’t easy. As a foreign national, it was hard to find a job so I applied for internships and did volunteer work in my first two years. Now, Amman is where I smell my mother’s bread cooking in the kitchen, and where I feel safe.

Endnotes

- “FACT SHEET > Yemen / June 2019,” UNHCR via ReliefWeb, June 2019, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Yemen%20Factsheet_June%202019%20%28Final%29.pdf

- “Yemen Regional Refugee and Migrant Response Plan,” Operational Data Portal operated by UNHCR, accessed December 20, 2019, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/yemen; “UNHCR Fact Sheet, Jordan, May 2019,” UNHCR via ReliefWeb, September 2019, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/71536; “UNHCR Fact Sheet, Egypt, August 2019,” UNHCR, August 2019, http://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/UNHCR%20Egypt%20Fact%20Sheet%20-%20August%202019_0.pdf

- “Yemen, Urban displacement in a rural society,” Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, October 2019, http://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/201910-urban-yemen_0.pdf

- “UNHCR Fact Sheet, Jordan, September 2019,” UNHCR via ReliefWeb, September 2019, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/71536

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية