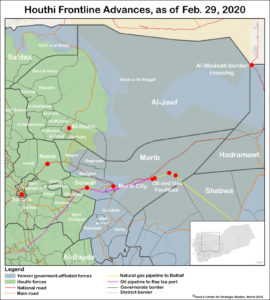

The fall of Al-Jawf to the armed Houthi movement significantly changes the course of the war in Yemen, militarily clearing the Houthis’ path to move into oil-rich Marib governorate, as well as politically and diplomatically in ongoing not-so-secret negotiations between the group and Saudi Arabia.

Al-Jawf’s capital, Al-Hazm, fell at the end of February with Houthi and government officials confirming on Sunday that Houthi forces controlled the capital, though Saudi airstrikes continued. By taking the capital, Houthi forces have cleared away the last obstacle in front of the vast, largely empty desert areas across the north of Marib. The Houthi movement, therefore, gains an easy military path to the vein of Marib’s wealth – its oil wells and a refinery – without having to capture Marib city, the governorate’s well-fortified capital. From there, Houthi forces could in theory advance on toward Shabwa in the south and Hadramawt in the east, but this would require securing all of Marib.

The capture of Al-Hazm follows other Houthi advances in late January. The group has recaptured key positions in the Nehm district of Sana’a governorate, about 60 kilometers northwest of the capital, near the border with Marib governorate; it also has a presence in Serwah district, 40 kilometers west of Marib city. These and the fall of Al-Hazm leave Houthi forces positioned not only to secure the SAFER oil pumps and refinery in the governorate but also to besiege Marib city itself and cut off the city’s supply routes, except for those to the south, toward Shabwa. Houthi forces can expect resistance and complications, especially from local government-allied tribes, should they continue to advance on oil areas. Yemeni government troops have a heavy presence in Marib, and some Saudi forces also are in the area. The reality of the army’s military power in Marib, however, is uncertain. The fragility of army forces was apparent with the fall of much of Nehm district and in their performance at Al-Hazm, making reliance on them a dangerous adventure.

The Houthi offensive included a ballistic missile strike February 21 on Saudi Arabia’s industrial city of Yanbu — a bold move against a city with an Aramco oil refinery — that disoriented a Saudi-Houthi partial truce that had held for four months. It came at a time of direct negotiations between Houthi authorities and the Saudis in Riyadh. Saudi Arabia had sought deescalation for several reasons, including the audacity and high cost of the September 2019 Aramco attacks claimed by the Houthis but believed to be Iranian in origin, the difficulty in holding its diverse coalition and Yemeni allies together, the fact that Riyadh would like to calm the situation ahead of hosting the G-20 summit later this year as well as the upcoming US presidential election, which could put American support for the Saudi war effort in Yemen at issue in the foreign policy debate. While the kingdom has many reasons for wanting to wrap up its involvement in the war, now entering its sixth year, it does not have a coherent political and military exit strategy. For the armed Houthi movement, Riyadh’s desire to seek a political solution emboldened the group to begin a decisive expansion into eastern Yemen.

The Houthis have a simple and successful strategy: pursue a facade of negotiations to help placate their rivals, all the while building their preparedness for a military strike. Thus, they benefit from the frailty of the Yemeni president and his government, which is manifest in its corruption, divisions and weak diplomatic and security performance. The Houthis are well aware of Saudi Arabia’s inability to resolve the infighting among its Yemeni allies or replace corrupt officers who have poor results in battle. These factors combined with the Houthis’ new military leverage could be used in negotiations to pressure the Saudis to decrease their support to their Yemeni allies in exchange for restoring calm on the borders and in Saudi cities. This latest Houthi offensive is bound to be particularly unnerving for Riyadh because the capture of Al-Jawf expands Houthi control into areas beyond Sa’ada governorate that directly border the kingdom. It puts the possibility of controlling Al-Wadeah border crossing — the last functioning border crossing that links Yemen with Saudi Arabia — within a stone’s throw of the Houthis. They may choose to avoid that potential confrontation with Riyadh and instead focus on controlling Marib and solidifying recent victories there.

Houthi achievements also greatly deepen differences between the government’s own political parties and foster distrust between Saudi Arabia and the Yemeni government. This is particularly true with regard to the Islah Party, which has the most control over both the government and over the governorates which are under Houthi attacks. In general, weakening Saudi-supported allies on the ground makes a Houthi expansion of territory, including advancing through Marib, more likely.

Ultimately, Riyadh is unlikely to accept any peace plan that leaves a direct threat on its border, and combined with the prospect of the internationally recognized government of Yemen losing control over Marib, one of its most strategically important and resource-rich areas, the latest escalation appears likely to get a lot worse before it gets any better.

Maged Al-Madhaji is a co-founder and executive director of the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. He tweets at @MAlmadhaji.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية