By Saad Hizam Ali

Introduction

With the Yemen war in its sixth year, the situation of public institutions in each governorate has changed in various ways. Marib governorate has become a destination for tens of thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) at a time from other areas, with the increase in population impacting the provision of public services. Marib also has become the site of some central government offices, which, like the families who have fled front-line areas, moved to the governorate because of its relative stability during most of the conflict.

In general, Marib has withstood the war better than other parts of the country, finding relative prosperity in its natural resources and its ability to secure claim to some of the revenues they provide that previously had gone to the central government. These revenues have helped Marib accommodate the 2 million to 3 million IDPs who have spent time in the governorate since 2014, according to the Central Statistical Organization in the governorate.[1] There are 126 IDP camps in Marib; the largest, Al-Juafainah camp in Marib city, houses more than 6,000 families.[2] Marib’s pre-war population was believed to be about 313,000 people.[3]

Structural adaptations and measures to develop the skills and capacities of employees of the governorate’s executive offices are needed to keep up with the needs of residents — permanent or transitory — as they arise. Such improvements are constrained, however, by the government budget, which has not changed since 2014 and does not include money for new hires in the civil service. Furthermore, most financial authority relating to the management of resources officially remains in the hands of the weak central authority. As a result, governorate- and district-level authorities and agencies have initiated some workarounds, but remain ill-equipped to function efficiently.

This study aims to provide a better understanding of the human resources currently available, their skills and capacities. It also considers the relationship between and designated roles of the local and central authorities. Information was gathered through field visits and interviews in February and March 2020 with members of local councils and public service employees at the governorate and district levels.

The author, a management development consultant, was hired by the Director General of the Civil Service Office to conduct training seminars in February and March 2020 with Marib’s general managers and executive offices. General managers and executive office employees spoke frankly about the challenges they face institutionally and in terms of trying to meet the needs of their communities, both permanent and temporary. Those interactions shaped the conclusions and recommendations outlined in this paper.

Marib: Context and Background

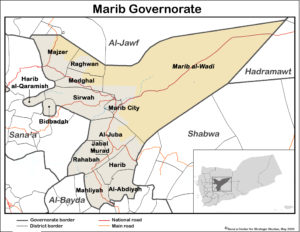

Marib governorate, located 173 kilometers northeast of Sana’a, is made up of 14 districts covering 17,405 square kilometers. The governorate is rich in natural resources, including oil, gas and minerals – which made it one of the first hotspots of the current war – as well as fertile agricultural land and groundwater resources. Yemen’s main oil refinery, operated by the SAFER Exploration & Production Operations Company, is located in Marib, and the governorate is the country’s main producer of liquified natural gas, which had been exported through the Balhaf facilities in neighboring Shabwa until the war escalated in 2015. Marib also has the largest gas-powered electricity plant in Yemen.

Marib was the first governorate to cut communications with the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) in Sana’a in November 2015, even before the internationally recognized government’s decision to move the CBY headquarters to Aden in September 2016.[4] This move granted the Marib central bank branch increased autonomy and independence in decision-making, with the most notable ramification being additional accumulation and control of local revenues. Marib’s governor, Sultan Aradah of the Abida tribe, Marib’s most influential tribe, struck a deal with the Yemeni government for Marib to keep 20 percent of local oil and gas revenues, which prior to the conflict all went to ruling authorities in Sana’a.[5] These additional revenues have helped Marib cope with the increased demand for services due to the influx of IDPs from other parts of the country.

The IDPs bring with them significant human and financial resources. Some have pursued investment opportunities in the governorate, while others have covered service gaps. Many IDPs have taken jobs in restaurants and hotels, which are in demand with the rising population. Doctors, accountants, engineers, university professors, teachers and other professionals also were displaced to the governorate, and some have been contracted by the local authority to help cover needs in the civil service. There is still, however, a need for more skilled workers.

Social affiliations are generally more important than political ones in Yemen, though in Marib tribal leaders are also the political leaders of the governorate — a situation that has minimized political conflicts and allowed for a united front against the Houthis. Local tribes in Marib have often proven influential and strong enough to challenge the authority of state institutions and agencies. The tribes’ abilities to coordinate, mobilize and secure financial benefits are significant strengths.

After the Saudi-led Arab coalition intervened in Yemen in March 2015, Marib hosted the command center of the Saudi and Emirati forces. The UAE, however, later withdrew from Marib after a Houthi missile killed 45 Emirati and five Bahraini soldiers there in September 2015.[6] Since 2017, when disputes started surfacing between President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi and his partner in the anti-Houthi coalition, the Southern Transitional Council (STC),[7] Marib also has become a safe haven for many officials and institutions of Hadi’s government wary of the interim capital Aden, where the STC holds sway.

The Structure of the Local Authority

The Marib local authority consists of the local council, which is led by the governor, and includes a secretary-general and one representative from each district. The governor is the highest official Marib, with the secretary-general of the local council stepping in if the governor is absent. The governor makes appointments and is the official representative of the governorate.

According to the 2000 Local Authority Law, the local council “is responsible for reviewing and approving draft comprehensive plans at the governorate level and overseeing their implementation, and it also directs, oversees, and supervises the activities of local councils in the districts and the governorate’s executive agencies.”[8]

Five specialized committees function in the governorate: Planning, Development, Finance, Services and Social Affairs. The heads of these five committees serve on an administrative body led by the governor with the secretary-general as deputy leader; majority votes carry decisions within this body.

Authority in the governorate rests largely within the Executive Office, which also is led by the governor; the secretary-general of the local council serves as deputy head. The Executive Office also includes the deputy governor and the directors of executive offices, which includes local branches of government ministries and the popularly elected bodies represented in the local council.

Public Sector Employees

Marib governorate employs 9,957 civil servants, according to the January 2020 payroll (See Annex A, Table 1).[9] They are distributed among 34 executive offices and institutions. The figure does not include employees of independent units or of central authorities in the governorate (for example, judges, government-owned banks, Saba University, the Central Organization for Control and Auditing, the oil and gas companies, the Safer refineries in Marib, and the Marib Hospital Authority).

Education (6,279 employees) and healthcare (1,488 employees) account for 78 percent of the governorate’s civil servants. Reliable district population figures are unavailable, but even these relatively well-staffed sectors are ill-positioned to respond to community needs on their own. Medghal district, for example, has no employees in the healthcare sector (See Annex A, Table 2). Yet it was one of four districts — the others being Marib city, Marib al-Wadi and Sirwah — that the International Organization for Migration identified as absorbing most of the 9,000-plus families that fled fighting between late January and April 2020.[10] Meanwhile, there are 313 employees still on the payroll of the health office who have either retired, died or are not working without justification.[11]

Education Snapshot

A Ministry of Education survey reported 462 primary and secondary schools, public and private, were operating in Marib during the 2013-2014 school year.[12] As of the 2019-2020 school year, there were 528, including 21 recently established private schools.[13] Beyond not keeping pace with the IDP influx, a local authority senior manager said many schools established during the war have been converted metal shipping containers or cloth tents erected as temporary solutions in IDP areas. These are unsuited to the governorate’s harsh desert climate. These schools also lack supplies, such as books and equipment, as well as suitable bathrooms for female students. Some also have more teachers than they need in some subjects and too few in others.[14]

According to the civil service database, 6,280 people are employed in the education sector in the governorate (Note: this figure differs by 1 from the 6,279 employees listed in the payroll database, meaning one employee has been administratively transferred, but not financially.) Only 14 held Master’s degrees, another 1,908 held Bachelor’s degrees, 1,354 had intermediate diplomas after secondary school, 2,647 had a secondary school diploma, and 357 had a lower level of education.[15]

Those with a bachelor’s degree make up no more than 30 percent of the total number of teachers and administrators, while those with a secondary-school education make up 42 percent of the total.

Healthcare Snapshot

Beyond the level of healthcare staff which includes only four specialists in the governorate, there is also a significant gap between the number of male and female healthcare workers (See Annex A, Table 3). Only 16 percent of health sector employees are female, with about 41 percent of these women working as midwives. Only four board-certified medical professionals and 41 general practitioners, including seven female doctors, are on the civil service payroll.

There are 101 government-run healthcare facilities throughout the governorate — 22 hospitals, 17 health centers and 62 smaller health units. Some of these facilities are managed and funded in cooperation with international organizations or their local partners.[16]

Civil Service Hiring Procedures

Civil service employment is regulated by the Civil Service Law (1991), containing articles related to salaries and wages and their regulation,[17] as well as Cabinet Decree No. 149 of 2007, which specifies who has the authority on appointment decisions.[18] Required qualifications and experience are outlined along with basic, required leadership qualities for higher-level administrative positions, including problem-solving, creative thinking and an ability to manage, assess and develop the abilities of others.[19]

The absence of a mechanism within the human resources department to accurately measure these requirements is a shortcoming that complicates implementing the criteria for working in public office. In practice, the assessment tends to be left to the discretion of the person nominating the applicant.[20] Because there has been no budget for new positions since 2014, exceptional approvals have been made in some areas, including healthcare, in an attempt to cover needs. Positions in independent units – such as state-affiliated banks, funds and companies – are financially and administratively approved within their own budgets, without the supervision of the local authority.[21]

According to the Local Authority Law, general managers of executive offices are appointed through Cabinet decisions after being nominated by the governor to the relevant minister.[22] Department heads and positions below general manager in the hierarchy are appointed by the governor based on nomination by the heads of the executive offices in the governorate. For district-level executive offices, the district manager nominates candidates for open positions who are then appointed by the governor. The president appoints governors, deputy governors and assistant deputy governors in accordance with Decree 149 (2007) regarding conditions for filling jobs.[23]

Conditional appointments for hospital and healthcare center managers are handled by the district general manager, then, after a six-month trial period, a final appointment decision is made based on the district general manager’s recommendation to the health office in the governorate.

Under Decree No. 149 (2007), general managers are required to have a college degree in a relevant field followed by 13 years of experience, a Master’s degree plus nine years of experience or a Ph.D. plus five years of experience. These requirements, however, are not enforced. The author was permitted to view, but not take a copy of, a list of the qualifications of general managers of the executive offices in Marib governorate. One of the general managers had a Ph.D., another had a Master’s degree and 26 had Bachelor’s degrees (24 of those 26 were education degrees). Six general managers had a secondary school education.

Ordinarily, appointment and nomination decisions are made for employees in certain positions, and there are hiring policies that dictate this process. Human Resources determines employment needs, which are included in the respective administrative unit’s budget for the coming year. After the budget is approved, the administrative unit is informed of the positions for each of its departments and open positions are announced through directives or through the civil service office. These procedures stopped in 2014 when government funding for new hires was halted due to lack of resources and political disagreements.

The local authority, seeking ways to deal with the ever-increasing staffing needs stemming from the rapidly growing population, came up with alternative solutions to hire and train staff[24]:

- The local authority contracted with 34 doctors with Arab Board certification to work in Marib hospitals, paying them from the development account.[25]

- It contracted 340 teachers from among the IDPs to cover some school needs.

- A line item for training was approved in the annual budget for each executive office, though managers within the offices say the funds are not enough.

- Ad hoc requests from executive offices are, at times, approved by the governor. Some of the needs are met based on requests from the entities. For example, the Civil Service Office received approval for funds from the development account to carry out three training programs in January and February 2020 for governorate leaders in strategic planning, human resources information systems, and budget preparation. This was granted outside of the approved training budget, which is about 2 million Yemeni rials a year.[26] (Note: These programs included the training sessions conducted by the researcher in Marib governorate during this time period.)

Outdated, Competing Laws Govern Control of the Purse

Beyond the 34 executive offices within the jurisdiction of the local authority are several operating under the central authority.[27] These offices are specifically for the Central Organization for Control and Auditing, the Marib Hospital Authority, the branch of the Central Bank of Yemen, government-owned and mixed-ownership banks including the Cooperative and Agricultural Credit Bank and the Yemen Bank for Reconstruction and Development, as well as the university, oil and gas companies, and the refineries.

Local Authority Law No. 4 of 2000 and its executive regulations regulate the tasks, specializations and authorities of the central government, the governorate and the districts, as well as the relationships among them, their shares of financial revenues and funds, organizational levels, special exceptions, the mechanism and scope of oversight, and legislative references.[28]

According to heads of the executive offices, powers granted to governorate authorities are insufficient in regard to financial or administrative resources, the revenue base and mechanisms to collect and oversee revenues. Most such powers remain at the central level. Financial management, for example, was granted complete independence from the local authority in accordance with Financial Law No. 8 of 1990, and was not amended to reflect powers granted to the local authorities by Law No. 4 of 2000.

Laws, however, have not been adapted to the new reality in the governorate in general. This is despite the fact that some of the outcomes of the National Dialogue Conference with regards to the governorate concerning mineral and petroleum resources are being implemented, such as the development account and deal for Marib to keep 20 percent of revenues from oil and gas.

Conclusion

Marib authorities are aware of many of the institutional challenges they face, which if addressed could help them meet more of the immediate needs of their permanent and temporary residents and plan for emerging societal challenges.

Through interviews conducted with governorate leaders and during time spent reviewing executive offices in the governorate as well as training these office leaders in strategic planning, human resources, information systems, budget preparation and shifting to program budgets, the following issues became apparent:

- A clear strategy is lacking to develop and build the capacity of the human resources. Sound planning and a strategy to clarify how work is carried out also are absent.

- Weaknesses exist in the administrative oversight system and in the professional cadre in general, which has a poor understanding of the systems and regulations governing their work. Senior managers need to further develop their skills in strategic planning, institutional assessment, quality management, decision-making and crisis management. The same applies to mid-level managers, who also require assistance in developing their skills to supervise, communicate, prepare operational plans and set priorities. It is also important to develop teamwork and report-writing skills on all administrative levels, including in technical positions.

- Administrative neglect is an issue: For example, work was carried out just 2.5 hours a day (9:30 a.m. to 12 p.m.) in most public offices visited by the author.

- Organizational structures are vague. Because these structures are based on those of the central government, positions tend to be created to suit an individual and lack guidelines for tasks and requirements.

- Formal oversight is weak, inflexible and ineffective, and there is an absence of assessment and evaluation. This can be attributed to the fact that each entity’s role and work mechanisms are unclear in local authority laws.

Beyond such institutional weaknesses, which the local authority retains a degree of control over addressing, are broader issues complicating efforts to address residents’ needs.

- Powers granted to governorate authorities are insufficient in regard to financial resources, administrative authority, the revenue base and mechanisms to collect and oversee revenues. With the central government empowered to organize and oversee financial administration, the role of the local authority is diminished.

- Administrative powers are limited to appointments to supervisory positions and positions lower in the hierarchy; independent bodies and institutions and oversight agencies remain subject to the central authorities.

- Existing regulations related to governorate and district offices are uniform; they do not take into account the unique issues faced by each governorate or district. Because they have not been amended to take into account the extraordinary situation in Marib since the conflict began, main and subordinate positions have been created outside the unified organizational structure.

Recommendations:

To the Local Authority in the Governorate:

- Prepare a methodology for planning and training in the field of human resources, determining needs, preparing work guidelines, governance, using computers and statistical analysis systems, coordinating with the central government to increase allocated funds for training, and including the cadres of the governorate in training programs provided within agreements with other countries.

- Include creative-thinking curricula in education, expand literacy programs and train educators in the use of modern educational tools, such as smart boards.

- Review organizational structures to assess their suitability for the tasks and specializations of each administrative unit, complete the information infrastructure for the local authority and increase official and community accountability.

- Prepare specific mechanisms and procedures to capitalize on the skills and experience among the IDPs, integrate them into public institutions and organize their living conditions to more efficiently provide them with public services. This process should be preceded by a comprehensive analysis of IDPs’ situation, capabilities and resources.

To the Central Government and the Parliament:

- Institute regulations that clearly specify the organizational hierarchy of employees among various levels of authority, unify the financial incentives system and implement a competitive system for jobs. In conjunction with this, increase employees’ understanding of work rules and regulations, prepare studies and research for a clearer vision of the relationship between the various levels of authority, and find mechanisms to encourage proper distribution of cadres among districts, especially remote ones.

- Expand powers granted to governorate authorities with regard to financial and administrative resources to allow local authorities to collect and oversee revenue.

- Create a vision for easing local authorities’ dependence in terms of financial administration and their reliance on central organizational structures and central supervision over appointments, thus strengthening local authorities’ abilities to respond quickly and effectively to evolving community needs.

- Review regulations applying to governorate and district offices, ensuring they can be tailored to take into account unique circumstances faced by individual governorates.

Saad Hizam Ali is a management consultant in administrative development. He previously held positions in the Yemeni civil service, including Director General of Control and Inspection, Director General of the State Budget, Director General of Human Resources and Director General of the Information Technology Center, and head of the central unit of the biological fingerprint of the public service units. His research focuses on corruption, information systems, and transition policies toward electronic management.

This paper was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies with Oxford Research Group, as part of Reshaping the Process: Yemen program.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Oxford Research Group (ORG) is an independent organization that has been influential for nearly four decades in pioneering new, more strategic approaches to security and peacebuilding. Founded in 1982, ORG continues to pursue cutting-edge research and advocacy in the United Kingdom and abroad while managing innovative peacebuilding projects in several Middle Eastern countries.

Endnotes

- Author interview with the head of the Marib Statistics Office, March 2020.

- Author interview with Saif Muthana, manager of the Executive Unit in Marib, March 19, 2020.

- “Statistics Yearbook 2014 [AR],” Central Statistical Organization – Yemen, http://www.cso-yemen.com/content.php?lng=arabic&id=553

- Mansour Rageh, Amal Nasser and Farea Al-Muslimi, “Yemen Without a Functioning Central Bank: The Loss of Basic Economic Stabilization and Accelerating Famine,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 3, 2016, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/55

- Ben Hubbard, “As Yemen Crumbles, One Town Is an Island of Relative Calm,” The New York Times, November 9, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/09/world/middleeast/yemen-marib-war-ice-cream.html

- “Yemen: The death of 45 Emirati and 5 Bahraini Soldiers,” Russia Today, September 5, 2015, https://arabic.rt.com/news/793081

- “Introduction to the Southern Transitional Council in Yemen and Aidarous Al Zubaidi [AR],” BBC Arabic, January 29, 2018 https://www.bbc.com/arabic/in-depth-42860424

- Local Authority Law (2000) available here (Arabic and English): http://constitutionnet.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/Law%202000%20local%20authorities.pdf

- Based on Marib governorate’s civil payroll for civil service employees in January 2020, viewed by the researcher in March 2020.

- “IOM Yemen, Displacement in Marib, 22 April 2020,” International Organization for Migration via ReliefWeb, April 22, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/iom-yemen-displacement-marib-22-april-2020

- Author interview with the head of human resources in the Marib Health Office, March 2020.

- Central Statistical Organization, Statistical Yearbook 2014, http://www.cso-yemen.com/content.php?lng=arabic&id=680

- Information gathered from the Statistics Department in the Education Office of Marib governorate, March 2020.

- Interview with the head of human resources in the Marib Health Office, Marib city, March 2020.

- Based on Marib governorate’s civil service database for education employees in January 2020, viewed by the researcher in March 2020.

- Author interview with the manager of the Statistics Department – Marib Health Office, March 2020.

- Articles related salaries and wages from the Civil Service Law (2001) [AR]. Available via the Republic of Yemen Ministry of Finance website, https://www.mof.gov.ye/index.php?view=article&id=1079%3Astrategy-wage-law&option=com_content&Itemid=289

- Prime Minister Decree No. 149 of 2007 concerning the appointments system, https://issuu.com/gdaiya/docs/

- Ibid., Article 1, Paragraph A.

- Author interviews with Marib public sector employees requiring anonymity in order to discuss sensitive issues, February – March 2020.

- Author interview with Saud al-Yosifi, General Manager of the Marib Civil Service Office, March 19, 2020.

- Local Authority Law (2000) available here (Arabic and English): http://constitutionnet.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/Law%202000%20local%20authorities.pdf

- Prime Minister Decree No. 149 of 2007 concerning the appointments system, https://issuu.com/gdaiya/docs/___________________________________

- Interviews with the managers of the Civil Service, Education, Health and other executive offices in Marib, March 2020.

- A special account created by the Marib local authority based on outputs of the National Dialogue, which stipulated governorates be allocated 20 percent of oil and gas resources in a local development account.

- Interview with Saud al-Yosifi, General Manager of the Marib Civil Service Office, March 19, 2020.

- Interview with the head of Monitoring and Inspection, Marib Civil Service Office, March 19, 2020.

- Local Authority Law (2000) available here (Arabic and English): http://constitutionnet.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/Law%202000%20local%20authorities.pdf

-

Discrepancies exist between the Marib governorate payroll and civil service database. There is one additional employee in the education sector listed in the payroll and not in the database. In the healthcare sector, there is a difference of 312 individuals listed on the payroll vs the database. This is likely attributable to the figure cited by human resources at the Health Office of 313 employees who are still on the payroll of the health office, but have either retired, died or are not working without justification.

Annex A: Tables

Table 1: Civil Servants in the Executive Offices of the Governorate

|

# |

Entity |

Number |

Percentage |

|

1 |

Education |

6,279 |

63.1 |

|

2 |

Public Health and Population |

1,488 |

14.9 |

|

3 |

Agriculture and Irrigation |

428 |

4.3 |

|

4 |

Local Administration |

267 |

2.7 |

|

5 |

Finance |

256 |

2.6 |

|

6 |

Industry and Commerce |

164 |

1.6 |

|

7 |

Antiquities |

160 |

1.6 |

|

8 |

Public Works and Roads |

130 |

1.3 |

|

9 |

Roads and Bridges |

113 |

1.13 |

|

10 |

Technical Education |

110 |

1.1 |

|

11 |

Sanitation Fund |

88 |

0.9 |

|

12 |

Petroleum and Minerals |

72 |

0.7 |

|

13 |

Civil Service and Insurance |

64 |

0.6 |

|

14 |

Culture |

39 |

0.4 |

|

15 |

Tax Authority |

33 |

0.3 |

|

16 |

Tourism |

30 |

0.3 |

|

17 |

Social Affairs and Labor |

29 |

0.29 |

|

18 |

Youth and Sports |

28 |

0.28 |

|

19 |

Social Welfare Fund |

28 |

0.28 |

|

20 |

Planning |

25 |

0.25 |

|

21 |

Information |

24 |

0.24 |

|

22 |

Endowments and Guidance |

19 |

0.19 |

|

23 |

Expatriate Affairs |

14 |

0.14 |

|

24 |

Transportation |

14 |

0.14 |

|

25 |

Marib Radio |

14 |

0.14 |

|

26 |

Legal Affairs |

10 |

0.10 |

|

27 |

Land and Survey |

7 |

0.07 |

|

28 |

Statistics |

7 |

0.07 |

|

29 |

Martyrs’ Families |

6 |

0.06 |

|

30 |

General Organization for Books |

5 |

0.05 |

|

31 |

Literacy and Adult Learning |

2 |

0.02 |

|

32 |

Saba News Agency |

2 |

0.02 |

|

33 |

Environmental Protection |

1 |

0.01 |

|

34 |

General Investment Authority |

1 |

0.01 |

|

35 |

Total |

9,957 |

100 |

Source: Marib governorate civil service payroll (January 2020)

Table 2: Entities with Highest Number of Employees by District

|

# |

District |

Education |

Healthcare |

|

1 |

Local authority* |

430 |

190 |

|

2 |

Marib city |

696 |

104 |

|

3 |

Marib al-Wadi |

1,136 |

134 |

|

4 |

Bidbadah |

201 |

54 |

|

5 |

Jabal Murad |

206 |

113 |

|

6 |

Al-Juba |

900 |

110 |

|

7 |

Harib |

1,014 |

118 |

|

8 |

Harib al-Qaramish |

142 |

30 |

|

9 |

Rahabah |

219 |

59 |

|

10 |

Raghwan |

103 |

20 |

|

11 |

Sirwah |

595 |

95 |

|

12 |

Al-Abdiyah |

165 |

39 |

|

13 |

Mahliyah |

137 |

26 |

|

14 |

Majzar |

196 |

84 |

|

15 |

Medghal |

140 |

0 |

|

Total |

6,280 |

1,176 |

|

*Public sector employees at the governorate-level authority who are not assigned to a specific district

Source: Marib governorate civil service database29

Table 3: Distribution of Healthcare Cadres by Specialization

|

# |

Specialization |

Number |

Total |

|

|

Males |

Females |

|||

|

1 |

Specialists |

4 |

|

4 |

|

2 |

General Medicine |

34 |

7 |

41 |

|

3 |

Bachelor’s Degree in Community Health |

6 |

|

6 |

|

4 |

Bachelor’s Degree in Dentistry |

6 |

1 |

7 |

|

5 |

Bachelor’s Degree in Pharmacy |

10 |

|

10 |

|

6 |

Bachelor’s Degree in Medical Laboratories |

22 |

1 |

23 |

|

7 |

Bachelor’s Degree in Nursing |

3 |

|

3 |

|

8 |

Bachelor’s Degree in Hospital Administration |

2 |

|

2 |

|

9 |

Other Bachelor’s Degrees |

27 |

|

27 |

|

10 |

Doctor’s Assistant Diploma |

102 |

3 |

105 |

|

11 |

Pharmacy Diploma |

29 |

1 |

30 |

|

12 |

Medical Lab Diploma |

34 |

|

34 |

|

13 |

Radiation Diploma |

10 |

2 |

12 |

|

14 |

Public Health Diploma |

11 |

|

11 |

|

15 |

Nursing Diploma |

171 |

19 |

190 |

|

16 |

Physical Therapy Diploma |

3 |

|

3 |

|

17 |

Dentistry Diploma |

3 |

|

3 |

|

18 |

Surgery Diploma |

2 |

1 |

3 |

|

19 |

Medical Statistics Diploma |

3 |

|

3 |

|

20 |

Anesthesia Diploma |

5 |

|

5 |

|

21 |

Midwifery Diploma |

|

88 |

88 |

|

22 |

Other Diplomas |

11 |

|

11 |

|

23 |

Care Training Course |

29 |

14 |

43 |

|

24 |

Nursing Training Course |

3 |

|

3 |

|

25 |

Midwifery Training Course |

|

9 |

9 |

|

26 |

Secondary School |

183 |

37 |

220 |

|

27 |

Preparatory School |

83 |

20 |

103 |

|

28 |

Primary School |

71 |

14 |

85 |

|

29 |

None |

116 |

6 |

122 |

|

30 |

Not Working |

268 |

15 |

283 |

|

|

Total |

1,251 |

238 |

1,489 |

Source: Marib governorate’s civil service database (January 2020)

Annex B

Key questions posed in interviews with managers of executive offices – Marib

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية