Executive Summary

Climate change and its related impacts are evident in Yemen, including drought, extreme flooding, pest and disease outbreaks, rainfall pattern changes, increased frequency and severity of storms and rising sea levels. Together, they threaten the country’s natural systems and its communities that rely on natural resources. Al-Mahra governorate, where residents are heavily reliant on fishing, pastoralism and agriculture, is no exception to such climate change-induced destructive events, and its exposure to cyclones and floods has only been worsening in recent years.

Flash floods of 2008, tropical cyclones Chapala and Megh in 2015, and cyclones Sagar, Mekunu, and Luban in 2018 are examples of such extreme events that have caused loss of lives and livelihoods along with displacement and extensive damage to and destruction of houses, properties, farmlands, fishing equipment and infrastructure. More frequent and intense such storms are anticipated, directly impacting Mahris’ livelihoods.

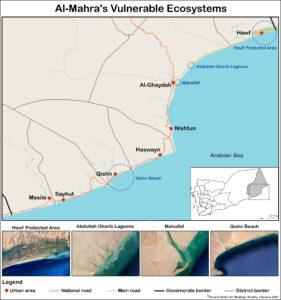

Al-Mahra’s prevailing semi-arid climate together with its geographical characteristics have created a broad array of habitats and rich systems that support an appreciable assemblage of rare and endangered native species of flora and fauna. Important biodiverse systems in the governorate vulnerable to climate change impacts that require special consideration include the Hawf Protected Area, Abdullah Gharib Lagoons and Qishn Beach.

This paper highlights some key climate change concerns relevant to Al-Mahra, and aims to bring to the attention of stakeholders and decisionmakers some of the vulnerabilities requiring consideration when setting policies, strategies and programs in preparation for future extreme events in Al-Mahra. Experts interviewed for this report all pointed out the need for better preparation to manage the impacts of the changing climate. However, constraints exist in terms of availability of data and there are significant gaps that require field research into socioeconomic and local circumstances in Al-Mahra. Next steps and recommendations identified include:

- Carry out a comprehensive Vulnerability & Adaptation assessment;

- develop, approve and implement a disaster response plan;

- establish an emergency fund for natural disasters at the governorate level;

- develop and implement an awareness program on climate change-induced risks and disasters;

- develop an integrated land-use management plan;

- conduct Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) as an integral part of development activities; and

- activate and enforce the existing management plan for the Hawf protected area.

Introduction

Policy documents and technical reports developed in the context of climate change in Yemen concur that climate change is an evident phenomenon that threatens Yemen and its local communities, biodiversity systems and natural resources. Yemeni environmental officials have warned for more than a decade that the nation, which is categorized among the least-developed in the world,[1] is “highly vulnerable to climate change-related impacts such as drought, extreme flooding, pests, sudden disease outbreaks, changes of rainfall patterns, increased storm frequency/severity and sea level rise.”[2]

Seasonal rain-fed agriculture is the mainstay of life in rural areas of Al-Mahra, as it is for many rural parts of the country, leaving Yemenis in general “highly reliant on favorable climatic conditions for their livelihoods.”[3] Local residents of inland areas engage in animal husbandry and cultivate crops for their families’ food needs and as a source of income, whether directly through farming or indirectly through trade in agricultural products. Coastal residents are heavily reliant on marine resources for their livelihoods, particularly fishing-related activities.

Al-Mahra also has an array of unique ecosystems, from coral reefs off its shore to sandy beaches and coastal area wetlands as well as mountain forests. Preparation to avoid exacerbating future climate-induced threats and impacts — whether to the governorate’s biodiverse environment or to its local population, infrastructure and economy — is required in decision-making processes at the national, regional and local levels.

This policy brief is meant to highlight some key areas and raise awareness among stakeholders, particularly planners and policymakers, about climate-related issues that should be considered while setting out policies, strategies and programs for Al-Mahra governorate. It also aims to provide guidance that would enhance resilience and build the adaptive capacity of vulnerable local communities in the face of climate changes as well as ease the impact of such changes on natural resources now and in the future.

Current data is limited for the subject area, Al-Mahra, and these gaps require a comprehensive assessment and field work that are beyond the scope of this policy brief. Therefore, a qualitative analysis approach was used to identify and analyze vulnerabilities and impacts of climate change; results presented are descriptive in nature.

Background

Al-Mahra governorate is situated in the eastern part of Yemen, with much of its population living in the provincial capital of Al-Ghaydah and in communities along the Arabian Sea. It has international borders with Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the east. It is administratively divided into nine districts that are further divided into sub-districts and then villages. The geography of Al-Mahra is characterized by coastal plains in the south, rigid mountain peaks with valleys channeling the seasonal tributaries that nourish small settlements and farmland, and the empty quarter desert lying to the north.[4]

Population

Al-Mahra’s population in 2004, the most recent census, stood at 88,594 — just 0.5 percent of the population as a whole — and was projected to grow 4.51 percent annually.[5] However, war-related internal population shifts have led to current estimates that vary widely, from 150,000 to 650,000 people.[6] Beekeeping, artisanal fishing and subsistence farming are the sort of fragile livelihoods Mahris commonly engage in that are highly vulnerable to climate-induced hazards and disasters such as floods, cyclones, storms and prolonged droughts.

The fisheries sector provides the main source of livelihood in Al-Mahra’s coastal communities. Shrimp from Al-Mahra is often exported abroad. Locally caught shark, salted and dried, is commonly sold mainly to Bedouins in the area, who consume it as a major source of protein. Sardines, a key component of livestock and camel diets, are another marine product important to the local economy.

Pastoralism and animal husbandry, particularly raising goats, sheep, cattle and camels, are important economically for Bedouins and others living in the sparsely populated inland areas. Water scarcity, limited arable land and desert conditions prevalent in much of the governorate limit the economic significance of other agricultural activities, though some grain, fruit and vegetable crops are locally grown.

Climate

Al-Mahra has a semi-arid climate characterized by sparse rainfall and seasonal monsoons, with high temperatures and high relative humidity, especially along the coast. Seasonal rains that fall in mountainous regions of the governorate during the southwest monsoon period (June — September) bring 400 mm to 700 mm of precipitation annually. An important phenomenon of this season is the fog that covers mountains, forming an additional source of water when harvested. According to a study conducted by the Agriculture Research and Extension Authority in 2002, 1-6 liters of water can be harvested from fog per square meter of the material used to collect the droplets.[8]

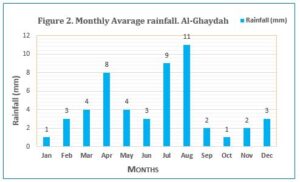

Monthly average maximum temperatures in Al-Ghaydah range from 28 degrees Celsius in January to 36 degrees Celsius in May and June. Monthly average minimums range from 16 degrees Celsius in January to 27 degrees Celsius in May and June (see Figure 1). Monthly rainfall averages range from 1 mm in January and October to 11 mm in August (see Figure 2).

Source: Compiled by the author from Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) data.[8]

Biodiversity

Like many other parts of Yemen, Al-Mahra’s biodiversity is rich and unique, in its coastal areas and in the mountainous region. This richness results from the various climate and geographical characteristics combining to create a broad array of habitats and systems that support an appreciable assemblage of rare and endangered native species of flora and fauna.

Source of images: Google Earth, accessed February 15, 2021.

Some of the governorate’s most important and most vulnerable biodiverse systems requiring action to reduce the impacts of climate change are:

- Hawf Protected Area: This forest system in eastern Al-Mahra on the Yemen-Oman border, roughly 120 kilometers northeast of Al-Ghaydah, covers 300 square kilometers. Its southern edge reaches the shoreline of the Arabian Sea, and it grades in height to 1,200 meters above sea level.[9] The forest contains more than 220 plant species, 56 of which are endemic or semi-endemic. Forest plants include 45 types of trees, 49 types of shrubs, 80 types of herbs and 27 distinct species of climbers and weeds. Twelve plant species are cultivated in the forest, including Frankincense, papaya and mango trees and bananas.[10] Wolves, caracals, ibex, hyenas and mongooses and badgers are among animals sheltered in the Hawf forest system. Among the 65 types of birds, including six rare species, are bustards, partridges, Arabian waxbills and eagles; the area also is home to a variety of reptiles.[11]

- Abdullah Gharib Lagoons: These wetlands consist of brackish to saline coastal lagoons of approximate total area of 100 hectares,[12] and are located about 20 kilometers northeast of Al-Ghaydah. They are especially important to gulls, terns and other water birds.

- Qishn Beach: This site is a stretch of gently shelving sandy beach, backed by sand dunes, covering approximately 100 hectares; it is considered highly sensitive to coastal erosion and inundation.[13] Qishn beach is especially important for Sooty Gulls, and has been identified as a potential nesting site for sea turtles.[14]

- Coral reefs: Like many other coastal areas of Yemen, coral reefs off Al-Mahra play an important role in the marine environment, providing unique habitats for a wide variety of marine species. Reefs also dissipate the energy of waves before they reach shore, thereby forming the first line of protection against coastal erosion and storm damage.

Vulnerabilities and Impacts of Climate Change:

Key vulnerabilities and impacts of climate change in Yemen have been clearly identified in previous policy documents, including the 2001 Initial National Communication (INC),[15] the 2009 National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA)[16] and the 2018 Third National Communication (TNC).[17] Although climate change is predicted to result in temperature increases for Yemen as a whole of 1.4 to 2.8 degrees Celsius by 2050, its impact on precipitation patterns is “more uncertain.”[18] Extreme weather events such as the cyclones, floods and droughts seen in recent years are expected to increase in frequency and intensity, with consequences for water resources, rural and coastal communities, the environment and infrastructure as well as agriculture, food security, public health and tourism.[19]

Flash flooding in 2008 that caused extensive damage to power lines, roads and water supplies in Al-Mahra killed at least five people and washed away about 3,000 homes and more than 600 farms in the governorate; about 450 fishermen lost equipment, including nearly 100 boats.[20] Floods, tropical storms, cyclones and depressions have been frequent and damaging in recent years. For example, two cyclones (Chapala and Megh) hit Yemen within a week in November 2015. Chapala caused significant flooding and the destruction of houses in four governorates — Hadramawt, Shabwa and Socotra as well as Al-Mahra, where health facilities in Sayhut, Qishn, Al-Ghaydah, Masila and Haswayn were damaged.[21] In the 2018 storm season, three cyclones struck Al-Mahra, Sagar and Mekunu in May and Luban in October. Mekunu sank boats in Al-Ghaydah and Al-Ebri, damaged homes and public buildings, including the Surfeit port office and schools in Haswayn and Khawlah, and wrecked telecommunications towers and agricultural equipment.[22] Luban killed at least three people, displaced thousands in Masila, Sayhut, Qishn, Huswain and Al-Ghaydah, and, for three days following its downgrade to a tropical depression, Luban’s heavy rain caused significant flooding that damaged roads and bridges and cut electricity and communications.[23]

Such intense storms carry with them indirect impacts. Stagnant floodwater, for example, creates a suitable environment for the outbreak and growth of water- and vector-borne diseases such as cholera and malaria. Cyclones also can create favorable breeding conditions for locusts, which was evident after Mekunu and Luban struck in 2018. They brought rain inland as far as the Empty Quarter desert, where breeding went unchecked for months. Through the first half of 2019, swarms then spread in Saudi Arabia and into parts of Yemen and southwestern Iran.[24] The UN Food and Agriculture Organization warned of a threat to crops in much of Yemen, including Al-Mahra, and advised control measures; there were reports of crop damage in parts of the country, though a “danger” warning, the highest threat level, was never issued.[25]

A warming of the climate likely would further alter the timing and intensity of such individual storms, and would impact water availability and quality, with groundwater sources at risk from sea water intrusion due to rising sea levels.[26] These consequences, in turn, would directly impact Mahris’ livelihoods, whether among the economically vulnerable communities in rural agricultural areas or coastal fishing villages.

Agriculture & Food Security

The 2009 EPA report noted temperature and precipitation changes as well as more frequent periods of drought could “lead to disastrous consequences for agriculture and food security” in the country as a whole.[27] Flooding caused by brief but intense rainstorms could erode fertile soil and, if followed by drought, further decay could occur as desertification sets in. For local communities, sources of income also would be lost.[28]

Abdul Hakim Rajeh, a biodiversity specialist at the Environment Protection Authority based in Aden, said flooding in Al-Mahra from storms of recent years has caused landslides and significant soil erosion and has uprooted vegetation in elevated areas. People in lower-lying agricultural areas, he said, saw their livestock and farmlands washed away.[29]

Coastal Communities

Rising sea levels and increased flooding could inundate and erode low-lying areas in Al-Mahra around coastal towns of Al-Ghaydah, Haswayn, Qishn and Sayhut. Fishery facilities, such as landing areas, ice and storage sites and seaside market stalls, would be among the public and private assets and infrastructure at risk.

Abdelnasser Kalshat, chairman of the Fisheries Authority in Al-Mahra, said small islands and land barriers appeared offshore, especially in the Mehaifef area, after the 2018 cyclones, apparently due to huge amounts of soil and farmland washed into the sea. “Overnight, not a single tree was left in some valleys,” Kalshat said, noting that the torrential rain and flooding had dramatically altered the topography of valleys and the established courses of wadis, the dry riverbeds that fill seasonally.

While damage from cyclonic events to fishing equipment, boats and coastal residents’ homes and communities has been severe in recent years, Kalshat said the fish production sector has seen positive storm impacts. Shrimp, for example, have appeared in large numbers in more than one area following floods. Types of fish previously unseen in the area also are being caught, which Kalshat characterized as good for fishermen. Squid populations, however, have diminished or disappeared in several locations, he said.[30]

Impacts on Habitats and Biological Diversity

As temperatures rise, and with rainfall patterns changing and the prospect of more severe drought depleting the soil, ecosystems would be altered in the mountains, impacting Al-Mahra’s biodiverse Hawf forest, and along Yemen’s coast. Al-Mahra’s coastal habitats such as Abdullah Gharib Lagoons, Qishn Beach and the coral reefs off the governorate’s coast, could be at risk of deterioration due to sea level rise, intense wave activity and more frequent and intense coastal storms and tropical cyclones.[31]

Rajeh, the biodiversity expert, said plantlife within the Hawf Protected Area has deteriorated because of extended droughts. New varieties of exotic plants have appeared, he said, competing with endemic species. Because of its higher elevation, Rajeh said the protected area was less affected by the severe storms of recent years than areas downstream, with landslides, soil erosion and uprooted trees confined more to the edges of the protected area.[32]

Salim Arfeet, manager of the Hawf Protected Area and acting director of the EPA branch in Al-Mahra, said that Hawf’s mountainous topography has meant torrential rainwater flows quickly toward low-lying areas and finally to the sea. Dams should be constructed, he said, so water routinely lost could be collected and stored for use during dry periods.[33]

Coastal area wetlands that are important sites for birds, such as the Abdullah Gharib lagoons and other coastal systems also are at risk of further deterioration. Rajeh said storm surges of recent years have intensified waves, which has severely eroded sandy beaches, and that seawater has reached roads before receding in some areas.[34]

Challenges & Recommendations:

Consequences of climate change can be severe, and particularly hazardous for environmental systems and vulnerable populations, depriving people of their homes, livelihoods and natural resources. Experts interviewed for this report all pointed out the need for better preparation to mitigate the vulnerabilities and manage the impacts of the changing climate. Local authorities have taken some steps toward these ends.[35] However, constraints in terms of availability of data and significant gaps that require field research into socioeconomic and local circumstances in Al-Mahra are needed to gain complete understanding of the vulnerabilities and impacts of climate change in the governorate.

For national Environmental Protection authorities:

-

Carry out a comprehensive Vulnerability & Adaptation assessment as the first step toward fully understanding climate change impacts and vulnerabilities in Al-Mahra. Such an assessment should address and cover several issues including:

- identification of existing environmental systems and habitats as well as kinds and numbers of endemic and endangered species of flora and fauna;

- surveys to collect accurate data on locations and size of lowland areas and wetlands that are subject to inundation due to rising sea levels;

- surveys to collect socioeconomic information to identify the magnitude and distribution of local communities and their livelihoods;

- inventories of public and private property within a specific distance of shoreline that could be affected by sea level rise;

- assessment of types and degree of sensitivities, vulnerabilities and impacts of climate change on environmental resources and vulnerable groups; and

- development of a set of recommended potential adaptation measures for climate change impacts and measures to build resilience of vulnerable natural resources as well as vulnerable communities and groups.

- Require Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) be conducted as an integral part of development activities.

- Develop and implement an awareness program on climate change-induced risks and disasters. It should be designed to target relevant stakeholders at all levels, including community-level groups such as NGOs, CSOs, and unions, decision and policymakers, individuals with technical expertise and students. Proposed activities would be aimed at creating a concrete foundation for individuals to build their resilience and capacity to adapt to short- and longer-term impacts of climate change, and could include: technical meetings, workshops, practical training, and production and dissemination of awareness materials such as leaflets, brochures, posters.

-

Update, approve and enforce the existing draft Management Plan for the Hawf protected area, which was discussed at local and national levels in 2004 but never approved or implemented. It would assist in:

- conserving plants and woodlands in order to maintain green cover, thereby mitigating soil erosion that could expand desertification;

- protecting endemic and endangered flora and fauna species and their habitats; and

- helping local residents understand and how to use the protected area’s environmental resources in a sustainable manner, and how to work together to protect the area’s limited resources.

For local authorities and civil society:

- Approve and implement a disaster response plan that identifies clear roles and responsibilities of different bodies and institutions at each stage of a disaster (pre-disaster, within and post-disaster) to ensure a smooth, coordinated response. Relevant stakeholders may include public authorities such as civil defense, health, housing and public works, environment, water and sanitation, and electricity. Civil society organizations (CSOs), nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and the private sector also need to understand and be involved in the plan.

-

Establish an emergency fund for natural disasters at the governorate level that would:

- include a mechanism to assist and compensate those most adversely affected, providing support to restore damaged assets, including structures, equipment and cropland, with the goal of speeding economic recovery;

- ensure the provision of necessary supplies and equipment prior to, during and after natural disasters; and

- provide resources to implement the disaster-response plan;

-

Develop an integrated land-use management plan to:

- control expansion of development activities, physical assets, infrastructure, and community settlements;

- avoid high-risk areas to reduce exposure to hazards or adverse events related to climate change; and

- protect sensitive and fragile environmental systems from deterioration as a result of uncontrolled human activities.

This paper was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies with the Oxford Research Group, as part of the Reshaping the Process: Yemen program.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Oxford Research Group (ORG) is an independent organization that has been influential for nearly four decades in pioneering new, more strategic approaches to security and peacebuilding. Founded in 1982, ORG has provided cutting-edge research and advocacy in the United Kingdom and abroad while managing innovative peacebuilding projects in several Middle Eastern countries.

Endnotes

- “Least Developed Country Category: Yemen Profile,” United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, based on 2018 data, accessed October 26, 2020, https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/least-developed-country-category-yemen.html

- “National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA),” Environment Protection Authority, Sana’a, March 2009, p. 1,

- Ibid.

- “Introductory profile on Al-Mahra Governorate,” National Information Center, [AR], https://yemen-nic.info/gover/almahraa/brife/

- Ibid.

- Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606

- “Preserving biodiversity in Hawf through promoting sustainable management of the protected area by local community,” unpublished draft report as part of a study conducted by the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) from July 2003—September 2004.

- “Climate data,” Global weather data of the SWAT website, https://globalweather.tamu.edu/

- “Natural Forests and Biodiversity [AR],” unpublished draft report obtained by the author, EPA, Republic of Yemen, August 2013.

- Ibid., p. 43.

- The EPA’s unpublished 2013 draft report, “Natural Forests and Biodiversity”, noted some of the specific species of animals and birds inhabiting Hawf protected area, including Canis lupus, Caracal caracal, Capra ibex, Hyaena hyaena, Ichneumia albicauda, Mellivora capensis, Chlamydotis undulata, Alectoris melanocephala, Estrilda rufibarba and Aquila (multiple species).

- “Third National Communication to the Conference of the Parties of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change,” Republic of Yemen Environmental Protection Authority, June 2018, p. 63, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/3490581_Yemen-NC3-2-Yemen_TNC_2018_Final.pdf

- “Third National Communication to the Conference of the Parties of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change,” Republic of Yemen, June 2018, p. 63, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/3490581_Yemen-NC3-2-Yemen_TNC_2018_Final.pdf

- Jeff D. Miller, “Yemen”, in: Andrea D. Phillott and Alan F. Rees (Eds.), “Sea Turtles in the Middle East and South Asia Region: MTSG Annual Regional Report 2018,” draft report of the IUCN-SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group, 2018, p. 182, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e4c290978d00820618e0944/t/5e4d930dee5bb23bd71662d3/1582142226102/mtsg-annual-regional-report-2018_middle-east-s-asia.pdf

- “Initial National Communication (INC),” Environment Protection Authority, Sana’a, April, 2001,

- “National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA),” Environment Protection Authority, Sana’a, March 2009, https://unfccc.int/topics/resilience/workstreams/national-adaptation-programmes-of-action/napas-received

- “Third National Communication to the Conference of the Parties of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change,” Republic of Yemen Environmental Protection Authority, June 2018, p. 63, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/3490581_Yemen-NC3-2-Yemen_TNC_2018_Final.pdf

- “National Adaptation Programme of Action,” Republic of Yemen, Environmental Protection Authority, April 2009, 2.2, https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/napa/yem01.pdf

- “Third National Communication to the Conference of the Parties of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change,” Republic of Yemen Environmental Protection Authority, June 2018, pp. 1, 42, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/3490581_Yemen-NC3-2-Yemen_TNC_2018_Final.pdf; “National Adaptation Programme of Action,” Republic of Yemen, Environmental Protection Authority, April 2009, p. 5, https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/napa/yem01.pdf

- “OCHA Situation Report No. 4 Yemen – Floods, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, November 7, 2008, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/5B2E7915FBCEFC5E492574FC00022D39-Full_Report.pdf

- “Situation report number 18, 26 October – 9 November 2015, Yemen conflict”, World Health Organization-WHO, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/WHO_Yemen_situation_report_Issue_number_18_26_October_-_09_November__final.pdf

- “Yemen: Cyclone Mekunu”, Information bulletin, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent societies, May 27, 2018, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/IB_YE2018.05.27.pdf

- “Yemen: Cyclone Luban Flash Update Number 2”, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs-OCHA, October 17, 2018), https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Cyclone%20Luban%20Flash%20Update%202.pdf

- “Locust Watch: Current upsurge (2019-2021),” UN Food and Agriculture Organization, accessed February 4, 2021, http://www.fao.org/ag/locusts/en/info/2094/index.html

- “Locust Watch: Desert Locust risk maps – 2019,” UN FAO, accessed February 4, 2021, http://www.fao.org/ag/locusts/en/archives/1340/2470/2454/index.html; “Yemen appeals for international support amid ‘massive’ locust outbreak,” The National, July 19, 2020, https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/mena/yemen-appeals-for-international-support-amid-massive-locust-outbreak-1.1051228

- “National Adaptation Programme of Action,” Republic of Yemen, Environmental Protection Authority, April 2009, p. 5, https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/napa/yem01.pdf

- Ibid.

- “National Adaptation Programme of Action,” Republic of Yemen, Environmental Protection Authority, April 2009, p. 5, https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/napa/yem01.pdf

- Abdul Hakim Rajeh, telephone interview by the author, November 15, 2020.

- Abdelnasser Kalshat, telephone interview by the author, November 15, 2020.

- “National Adaptation Programme of Action,” Republic of Yemen, Environmental Protection Authority, April 2009, p. 5, https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/napa/yem01.pdf; “Third National Communication (TNC),” Environment Protection Authority, Sana’a, June, 2018,

- Abdul Hakim Rajeh, telephone interview by the author, November 15, 2020.

- Salim Arfeet, telephone interview by the author, November 17, 2020.

- Abdul Hakim Rajeh, telephone interview by the author, November 15, 2020.

- In October 2020, local authorities in Al-Mahra and neighboring Hadramawt gathered in Mukalla city, where they discussed climate change and produced some natural disaster response recommendations that have been forwarded to leaders of both governorates. They included establishing and operating an early warning center; preparing a joint response plan for the two governorates; establishing an emergency fund for natural disasters; and establishing and updating databases related to natural disasters and response operations.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية