Executive Summary

Yemen’s most easterly and isolated governorate of al-Mahra, to date spared the horrors of war experienced in much of the rest of the county, now faces destabilization due to a geopolitical struggle for influence involving Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Oman. Muscat has since the 1970s regarded al-Mahra as a natural extension of its national security sphere; in the decades following Riyadh pursued efforts to build an oil pipeline through the governorate to the Arabian Sea; Abu Dhabi’s interests in al-Mahra have only come to the fore since the beginning of the current Yemen conflict.

Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have, under the guise of their ongoing military intervention in Yemen, sought to pursue their vested interests in al-Mahra. The UAE’s efforts between 2015 and 2017 to build influence in the governorate were eventually rebuffed by local opposition to foreign interference. Mahris have a unique history of running their own affairs as well as a common vision of sovereignty within a federal system that has kept them remarkably unified. Saudi Arabia, however, has leveraged its sway over the internationally recognized Yemeni government to force the replacement of uncooperative officials in al-Mahra and the appointment of pliant replacements, and in late 2017 Riyadh began deploying armed forces in al-Mahra under the premise of combating smuggling across the Omani border.

Today, Saudi Arabia controls the governorate’s airport, border crossings and main seaport, and has established more than a dozen of military bases around the governorate where it has stationed thousands of its own troops and Yemeni proxy forces imported from other southern governorates. The deep-seated sense of local identity has spurred a growing opposition movement to the Saudi presence in al-Mahra – an opposition movement Oman has actively supported. While this opposition began as peaceful demonstrations, in more recent months there have been clashes with Saudi forces, with the Saudi air force carrying out airstrikes against Mahri tribesmen.

This paper lays the context for the evolving power struggle by examining al-Mahra’s unique character and history, and developments since the 2011 Yemen uprising. It then details the dynamics between the various local and regional actors to shed light on the myriad factors contributing to the current tension in one of Yemen’s most underreported regions.

Historical and Cultural Background

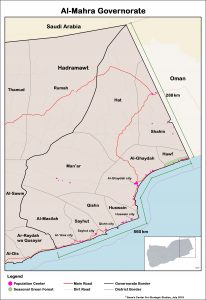

Al-Mahra is Yemen’s second-largest governorate by size and the easternmost region in the country. It is bordered by Oman to the east, Saudi Arabia to the north, Hadramawt governorate to the west, and the Arabian Sea to the south. Its 560-kilometer coastline is the longest of any Yemeni governorate. The Empty Quarter, a vast desert, covers much of southern al-Mahra, while the governorate also contains a mountainous region in the east that is seasonally covered with lush green foliage.[1]

The governorate, covering some 67,000 square kilometers, is divided into nine districts, with the main urban centers located in coastal areas. The largest city is al-Ghaydah, the capital of the governorate, followed by Sayhut, Qishn, Huswain and al-Aiss. Recent census data is unavailable, but extrapolating from a 2004 census using average population growth rates – which would not account for immigration or emigration – the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimated in 2017 that the governorate would have 150,000 residents. Academic estimates put the figure closer to 350,000, based on South Yemen’s first and most reliable census in 1973 and UN projected growth figures. According to a memo recently published by the governor, al-Mahra’s population including internally displaced persons (IDPs) is now around 650,000.[2] The main drivers of the local economy are al-Mahra’s fishing industry, agriculture, animal husbandry and customs revenues generated from the governorate’s border crossings with Oman.[3]

Al-Mahra’s population is mainly tribal. The tribes, known collectively as the Mahri, spread beyond the official borders of the governorate – which are only vaguely defined in some places – into neighboring Hadramawt governorate, in addition to Saudi Arabia and Oman. Residents of Hawf district, southeast along the coast, share tribal links with Oman’s Dhofar governorate, and many families possess dual nationalities and homes on both sides of the border. A similar context is also visible near Kharkhir, a village in Saudi Arabia, with members of the Samouda tribe living on either side of the border. While the Samouda in Kharkhir are generally isolated from their fellow tribesmen across the border, tribes that straddle the Yemen-Oman border are allowed to move freely up to 20 kilometers on either side as a result of a 1992 border agreement between the Omani and Yemeni governments. Mahris are almost universally adherents to Sunni Islam, with a strong tradition of Sufism within local society.[4]

Al-Mahra’s geographic isolation and history have endowed it with a culture distinct from other areas of Yemen. Al-Mahra’s tribes speak a unique Semitic language known as Mehri. Considered a Modern South Arabian language, it exists almost exclusively in spoken form. Mehri shares similarities with other regional dialects. Mahris understand the local Socotri language and, to an extent, the Jibbali that is spoken in the Omani governorate of Dhofar. Up until 1967, al-Mahra was effectively a separate entity from the rest of modern-day Yemen.[5] The Mahra Sultanate, which included both modern-day al-Mahra and the Socotra archipelago, was formed in the early 16th century and had no official constitutional system of governance. Instead, the sultan was traditionally chosen by consensus among the Mahri tribes, with the sultan making decisions based on tribal consultations and playing an integral mediating role in disputes. Given the collaborative nature of rule in al-Mahra, along with the fact that the sultan did not command any dedicated military forces, there were very few power struggles in the sultanate. During this period the al-Afrar family rose to prominence and established a hereditary dynasty. The Afrar sultans ruled al-Mahra and Socotra from their capital in Qishn, a town along the southern coast, with Fort Afrar still present in the village today.

Fort Afrar in the town of Qishn, which was the former residence of the Sultan of al-Mahra and Socotra. Pictured here on February 10, 2019.

Fort Afrar in the town of Qishn, which was the former residence of the Sultan of al-Mahra and Socotra. Pictured here on February 10, 2019.

In 1886, the Sultanate became a British Protectorate following the United Kingdom’s occupation of southern Yemen. However, this did not result in direct British rule in al-Mahra. The treaty signed between the Afrar sultan and British officials guaranteed that no other foreign power would be permitted to establish a presence in al-Mahra. During this period, the Mahra sultanate had international envoys to other Gulf statelets and an official sultanate passport. This helped facilitate residents’ travel to other Arab countries in search of work and served to establish lasting connections between Mahris and neighboring countries.

The region remained an independent sultanate until 1967 when British forces were expelled from southern Yemen after an insurgency by the Marxist-leaning National Liberation Front (NLF). Despite al-Mahra declining to align with the NLF against the British, and the Sultan advocating the need for continued protection against Marxist guerillas at the United Nations General Assembly in Geneva, Britain pulled all personnel out of the governorate in 1967, leaving al-Mahra to be overrun. Many Mahris were killed in violence that followed the British exit.[6]

After the end of the sultanate, al-Mahra became a governorate within the newly created People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen). Socotra was detached from al-Mahra and merged with Hadramawt governorate. Al-Mahra, along with the rest of South Yemen, unified with North Yemen to become the modern-day republic in May 1990.

Many Mahris perceive that their natural lands were divided during various points in history. This is the case not only with the international borders of neighboring Saudi Arabia and Oman, but also internal governorate borders demarcated by central Yemeni authorities. However, the lack of official border delineation and control in many places makes these divisions mostly present only on paper. Still, there is a popular sentiment among al-Mahra residents to redraw the official borders of the governorate within the Republic of Yemen. These demands mainly relate to reuniting al-Mahra and Socotra as a single region, and reclaiming areas that were historically considered part of al-Mahra but placed within Hadramawt governorate when the borders were drawn after becoming a part of South Yemen.

Al-Mahra and Gulf Countries

Al-Mahra possesses deep connections to neighboring Gulf states, particularly Oman and Saudi Arabia. Most families have relatives who have emigrated to a neighboring country for work or acquired a second citizenship. The reasons behind these connections are two-fold. First, al-Mahra’s borders with Oman and Saudi Arabia facilitated easy access. Second, Mahris were granted visa-free travel to the entire Arab world with the Mahra Sultanate passport.

The highest number of Mahris outside the governorate live in Oman. In addition to sharing a border, tribal links and a similar language, the people of al-Mahra and Oman’s Dhofar governorate share common customs, traditions and popular foods. The Dhofar Rebellion (1962-1976) in Oman was a seminal event in the country’s history, serving to emphasize the importance of al-Mahra to Muscat from a security perspective.[7] In response, Omani ruler Sultan Qaboos bin Said instituted policies to improve relations with al-Mahra’s population and build influence in the governorate. Along with granting many residents Omani citizenship, Muscat also affords free travel and employment rights to Mahris living in Oman. As a result, some Mahri families have foregone receiving Yemeni citizenship, particularly for their children born in Oman. However, Mahris without Omani citizenship or not living in Oman require a visa to enter the sultanate.

Saudi Arabia has the second-highest number of naturalized citizens from al-Mahra. Riyadh began establishing influence in the governorate in the 1980s through a naturalization campaign. Notable tribal sheikhs, including Abdallah bin Issa al-Afrar, son of the last ruling sultan, were granted Saudi residency, travel documents and financial benefits. The approach of cultivating ties and bestowing privileges to influential figures contrasted with the Omani approach, which provided citizenship to hundreds of Mahri families from all social backgrounds.

Saudi Arabia sought to build influence in al-Mahra as part of its ambitions to build an oil pipeline through the governorate to the Arabian Sea.[8] The proposed al-Mahra pipeline would likely entail significant economic and security benefits for Riyadh. Depending on the end destination, costs related to exporting Saudi oil would be reduced by allowing tankers to avoid the Bab al-Mandab Strait or the Strait of Hormuz. In addition, bypassing the Strait of Hormuz has immense implications for global oil security, given Iranian threats to close the waterway through which one-fifth of the world’s oil passes in any future conflict with Saudi Arabia or the United States.[9]

Discussions to build the pipeline began in the 1980s between Saudi Arabia and the government of South Yemen, according to former South Yemen President Ali Nasser Mohammed.[10] These talks failed but were revived after Yemeni unification in 1990. As part of the negotiations, Riyadh insisted then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh permit the deployment of Saudi forces in a 4-kilometer buffer zone around the proposed pipeline to maintain security. Saleh rejected this demand as an infringement on Yemen’s sovereignty, and the project was shelved.[11]

Given that the current Saudi military deployment in al-Mahra has given the Saudis de facto military control over large stretches of the governorate, many locals now believe Riyadh is exploiting the current situation to revive its aspirations for the construction of the oil pipeline.[12] Mahris generally oppose the project as an infringement on their sovereignty while Oman views the Saudi maneuvering as an encroachment on its sphere of influence.[13]

Passports issued by the former Sultanate of al-Mahra and Socotra. As written in the top-center page, these passports were “valid for all of the Arab World.”

Al-Mahra from the 2011 Revolution to the Ongoing Conflict

Before the 2011 revolution and Yemen’s subsequent descent into armed conflict, al-Mahra historically had not experienced the political or intellectual polarization seen in other areas of the country. Political parties were never able to gain a foothold in the governorate as the tribe remained the primary vehicle for political and social organization. While some political parties retained offices in al-Mahra, they did not have any substantial popular base. Thus, appointments to administrative positions in the local authority governing al-Mahra were based almost exclusively on tribal considerations. There was also a lack of incentive for political actors to invest in cultivating popular support in al-Mahra given its tiny population, relative to other governorates, that is dispersed across a large area.

Al-Mahra’s political and social isolation also served to keep the governorate at arm’s length from past episodes of civil conflict in the country, a trend that has continued during the current war. After the popular revolution that led to President Saleh’s resignation, representatives from al-Mahra attended the National Dialogue Conference (2013-14). This conference was meant to negotiate a peaceful transition away from the Saleh regime and decide on a new system of governance for the country. Among the proposals put forward during the conference was a plan for federalism in Yemen. While the Mahri delegation was supportive of this concept, it voted against new President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi’s proposed federal map, which would have divided the country into six regions, with al-Mahra and Socotra absorbed into neighboring Hadramawt governorate.[14]

Al-Mahra’s opposition to joining the Hadramawt governorate stemmed from fear of marginalization within the new entity. The Mahri people also did not want to see their unique culture and history as an independent entity eclipsed as a result of entering into a union with Hadramawt. Instead, Mahri representatives advocated that the governorate be joined with Socotra, as it was under the sultanate, to form an independent region in a new federal system.[15]

Following the Houthi takeover of Sana’a in 2014, al-Mahra aligned itself with President Hadi and the internationally recognized Yemeni government. After clashes in January 2015 between the armed Houthi movement and government supporters, Hadi tendered his resignation and was placed under house arrest, following which Hadi fled from Sana’a to Aden governorate. In February 2015, al-Mahra’s governor at the time, Mohammed Yasser Ali, called for Hadi’s reinstatement and rejected the Houthi takeover.[16] After Houthi forces and troops loyal to former President Saleh began to advance into southern areas of Yemen, Hadi was forced to flee again. This time, Hadi fled to al-Mahra, owing to its status as a safe and loyal governorate, and crossed the border into Oman. The local authority in al-Mahra later supported the March 2015 declaration of Operation Decisive Storm, the regional military intervention led by Saudi Arabia and the UAE in support of the Hadi government.[17]

Al-Mahra Adapts its Economy During the Conflict

President Hadi’s escape to Oman and the collapse of Yemen’s state apparatus caused negative economic consequences for al-Mahra during the early stages of the conflict, as it did throughout the country. In 2015, the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY), in an attempt to protect its currency reserves, slashed almost all financial transfers to the governorates for non-essential spending. By August 2016, with its reserves nearly exhausted, the CBY ended financing for almost all public spending – most importantly, ending regular salary payments to the majority of the 1.2 million Yemenis on the public payroll.[18] As a result, non-Mahri security forces and state employees who were managing the border crossing with Oman returned to their native governorates. The Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) also stopped supplying fuel to al-Mahra.[19]

Bereft of central government support, the local authority in al-Mahra began to develop independent solutions to ensure the governorate’s economic stability. Then-governor Mohammed Yasser Ali first reached out to Oman, which agreed to provide diesel for the al-Mahra branch of the General Electricity Corporation based in al-Ghaydah. Ali also created the Committee of Petroleum Products, which allowed traders to import and sell oil products in the governorate in return for paying taxes to the local authority, replacing the functions of the state oil company. To facilitate the tax payments, Ali opened a bank account at a local money exchange institution. Although Ali’s decision was technically illegal (trade in oil in Yemen was a state monopoly by law), it managed to both resume oil imports to al-Mahra and provide revenues to finance the governorate’s budget.

To address the security vacuum following the withdrawal of government security forces, Governor Ali handed control over the Shahin and Sarfait border crossings with Oman to local tribes. During the conflict, most of Yemen’s official points of entry – land, sea and air – have become inoperative. However, given the relative stability enjoyed in al-Mahra, the border crossings with Oman became an increasingly important route for traders shipping goods into the country.[20] This led to an increase in customs revenues, although corruption at the border crossing was rampant, with tribes often taking bribes from smugglers and traders to look the other way or allow goods into the country without full customs fees.[21]

At the beginning of 2016 a new governor was appointed, Mohammed bin Kuddah, who took steps to improve customs collections at the border crossings.[22] He replaced the tribes managing security at the crossings with personnel from the local authority security forces and instituted new import regulations. Additional customs clearance offices were set up, speeding up processing at the border. The governorate also significantly reduced customs on imported goods, providing an incentive for importers and traders to reroute shipments that otherwise would have entered Yemen through the ports of Hudaydah or Aden. Revenues increased for al-Mahra, despite the discounts. Bin Kuddah, in an interview with this author, said the increase in customs revenues from Shahin border crossing significantly bolstered the governorate’s budget and allowed it to pay local civil servant salaries.[23] This policy was reversed in August 2018, when the local authority in al-Mahra took a decision to increase custom fees on imported goods by 100 percent.[24]

Mahri tourists in the Hawf Nature Reserve, July 27, 2018.

The UAE Attempts to Gain Influence in Mahra

Coalition representatives from the UAE arrived in al-Mahra in August 2015 under the mission of supporting the local authority and maintaining security in the governorate. The UAE’s initial objective was to assist the al-Mahra local authority in building up its security forces. A decision was reached between the Emiratis and then-governor Ali to recruit and train 2,000 locals. However, a power struggle soon emerged regarding control over the nascent force. The UAE proposed recruiting soldiers via local sheikhs and training the recruits at the Khalidiya Camp in Hadramawt, the base for the Emirati-backed Hadrami Elite Forces. Ali rejected these terms and insisted that recruitment and training would be conducted under the overall supervision of the local authority.

To settle the dispute, Ali formed a committee composed of officials from the local authority and the security services. The committee proposed that it would directly supervise recruitment of locals to the security forces and that training would be conducted in al-Ghaydah, the capital of al-Mahra. The recruits also would be trained by officers from the Yemeni army and security services, with Emirati military officials acting in an advisory capacity. Although the UAE was displeased with the pushback, it agreed to the terms.[25] Recruitment was opened and the committee received 4,000 applicants, out of which 200 were chosen for the first class. However, before training could commence, Ali was removed by President Hadi. In November 2015, Bin Kuddah was appointed in his place.

Governor Bin Kuddah initially proved to be more flexible and accommodating to the coalition than his predecessor, which strengthened relations between the UAE and the local authority. In a sign of the governorate’s gratitude for Emirati support, Bin Kuddah named the first class of security forces, which graduated in May 2016, after Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan al-Nahyan, the founding father of the UAE. He also agreed that the second batch of Mahri recruits could be trained directly by Emirati officers at the Khalidiya Camp in Hadramawt. In response, the UAE increased its direct support for governorate. The Emirati Red Crescent Society began to distribute humanitarian aid to residents and 41 vehicles were supplied to the governor for the security administration of al-Mahra. However, this cordial period would not last; relations soured following the UAE’s attempts to place newly formed forces directly under their command and bypass the local authority.[26]

Pressure mounted on Bin Kuddah, in particular from members of the local authority, who demanded that the governor take action to preserve the region’s independence in the face of Emirati efforts to marginalize local decision-makers. Many of these officials held close ties with Oman, which also viewed the increasing Emirati presence in their traditional sphere of influence with growing unease. Tension already existed between the two Gulf countries over Oman’s refusal to join the coalition against Houthi forces, along with the uncovering of an alleged Emirati spy network in Oman in 2011.[27]

The Omanis also enjoyed good relations with Bin Kuddah from his time as a political refugee in Oman. Leveraging its ties with Bin Kuddah and other officials in the local authority, Oman began to reassert its clout in al-Mahra. This started with additional economic support to complement the existing diesel shipments, including the delivery of 16 generators of 11 megawatt capacity in December 2016 to help cover al-Mahra’s electricity deficit.[28] This support helped immensely to alleviate regular electricity blackouts in the governorate.

At the beginning of 2017, Bin Kuddah told UAE officials that Mahri forces would only take orders from the local authority.[29] In this demand, Bin Kuddah was backed by Oman, the local authority, and the General Council of the People of al-Mahra and Socotra, a body of tribal leaders formed in 2012 and headed by Sultan Abdullah al-Afrar.[30] The Emiratis, viewing the opposition as a betrayal, fully withdrew from the governorate. UAE officials also took back the vehicles they had provided to the governor, saying they were going to be refurbished, however to-date the vehicles have not been returned.[31]

A soldier with the local authorities in al-Mahra mans the Tanhalen checkpoint on the main road in al-Ghaydah district, September 15, 2018.

A soldier with the local authorities in al-Mahra mans the Tanhalen checkpoint on the main road in al-Ghaydah district, September 15, 2018.

Attempted Emirati Comeback Via the STC

The formation of the Southern Transitional Council (STC) represented an opportunity for the Emiratis to try to reestablish influence in al-Mahra. The STC, which is primarily backed by the UAE, was declared in May 2017 in Aden. The council, headed by Aiderous al-Zubaidi – whom Hadi had dismissed as governor of Aden in April 2017 – advocates secession for the former governorates of South Yemen. After its formation, the STC began attempts to establish branches in former South Yemen governorates. Al-Zubaidi reached out to Bin Kuddah to offer him membership on the STC, but the governor refused, reiterating his loyalty to President Hadi and the internationally recognized Yemeni government. After this rejection, al-Zubaidi then offered Sultan Afrar a seat on the council representing both al-Mahra and Socotra governorates. After some hesitation, al-Afrar agreed and plans were made for the inauguration of an STC branch in al-Mahra.[32]

Sultan Abdullah bin Issa al-Afrar is the son of the last ruling sultan of al-Mahra Sultanate. He was only 5 years old when the sultanate was absorbed into South Yemen, which led to the confiscation of much of the family’s property and wealth, along with the trial of his father, Sultan Issa bin Ali al-Afrar, whose death sentence was commuted at the last minute by then-South Yemen President Salim Rubai Ali. Sultan Abdullah was later granted Saudi travel documents – as part of Riydah’s influence campaign in the governorate that began in the 1980s – and spent much of his life in the kingdom.[33]

Al-Afrar resurfaced as a public figure in Yemen in 2012. This occurred after a delegation of sheikhs visited him in Saudi Arabia and requested that he, as son of the last sultan of the former ruling dynasty, be the public representative of al-Mahra and Socotra governorates as head of the General Council of the People of al-Mahra and Socotra.[34] After accepting, al-Afrar continued to live between Saudi Arabia and al-Mahra until the sultan’s relationship with the Saudis began to deteriorate in 2017 and Riyadh refused to renew his travel documents.

Oman then invited al-Afrar to Muscat and offered him Omani citizenship. It also granted al-Afrar patronage privileges to help reinforce his standing with al-Mahra’s population, including the ability to sponsor Omani entry visas and residency permits. Media reports at the time characterized the Omani outreach to al-Afrar as a move to curb growing Emirati influence in al-Mahra.[35]

Al-Afrar is a popular and influential figure in al-Mahra, owing to his affiliation with the former ruling dynasty. Since returning to the governorate, al-Afrar has assumed the consultative leadership role held by his forebearers. He has taken pains to stress the unity of the people of al-Mahra and Socotra in public, often reiterating their shared common ground before discussing differences. Al-Afrar would later play a critical role as a figurehead of a popular opposition movement to Saudi Arabia’s presence in the governorate.

After several delays, the inauguration of the STC office in al-Ghaydah on October 30, 2017, revealed the incompatibility of the STC’s agenda with popular sentiment in al-Mahra. Prior to the ceremony, Bin Kuddah imposed several conditions on the STC, which included refraining from any speech that undermined the authority of the Yemeni government or provoked incitement against northerners. Sultan Afrar, in his speech at the inauguration, later welcomed the establishment of the STC office under the auspices of the legitimate Yemeni government, in direct contradiction to the STC’s secessionist ambitions.

On the same day as the ceremony, a security incident ended the STC project in al-Mahra before it even got off the ground. Mahri security forces arrested a group of armed men who were attempting to intercept a vehicle carrying prisoners to Hadramawt. Among the armed men was Qasim Thobani, head of the Shalal Shaea Security Department in Aden, and the prisoners whom he was trying to free were allegedly members of the Aden Security Belt forces. The prisoners were accused of killing three Hadrami tribesmen, and according to Ahmed Mohammed Qahtan, then-Director of General Security of al-Mahra Governorate, Thobani had previously requested that they be released.[36] When it was revealed that Thobani had come to al-Mahra as part of the STC security detail, there was local outrage and calls for an investigation into the STC leader al-Zubaidi’s connections to the attempted jailbreak. To quell the tensions, the STC head denied any affiliation with Thobani and requested the governor’s protection until he could safely leave the area. President Hadi later expressed his pleasure with the governor and the people of al-Mahra for their loyalty and willingness to uphold the government’s legitimacy.[37]

A truck at dawn preparations for a protest against the Saudi military presence in the Touf area of Hat district in al-Mahra, September 24, 2018.

A truck at dawn preparations for a protest against the Saudi military presence in the Touf area of Hat district in al-Mahra, September 24, 2018.

Saudi Arabia’s Campaign to Exert Control in Al-Mahra

In November 2017, al-Mahra was experiencing political, economic and security stability relative to the rest of the country. The General Council and local authority were aligned politically. The operational budget of the governorate, bolstered by increased customs revenues, was able to pay civil servant salaries – unlike most other governorates in Yemen. However, the deployment of Saudi forces that month brought a new period of political polarization over foreign influence in al-Mahra.

The Saudi military justified its intervention in al-Mahra under the need to curb arms smuggling through the governorate. Even before the current conflict, al-Mahra was known as a smuggling zone, with routes along the Omani and Saudi border in addition to the Arabian Sea coastline. Rumors about weapons smuggling to the Houthi movement via al-Mahra began in 2013, prompting Oman to build an electrified fence along portions of the border.[38] In early November 2017, the Saudi-owned television station Al-Arabiya broadcast a report alleging weapons were being smuggled to the Houthi movement via al-Mahra’s coast.[39] According to diplomatic sources who spoke to the Sana’a Center, US special forces were also deployed to al-Mahra in 2018 to support the coalition’s anti-smuggling operations.[40]

Tension between Saudi forces and locals emerged in al-Mahra from day one. On November 11, 2017, a detachment of Saudi soldiers flew into al-Ghaydah airport, accompanied by Saudi officers and 21 Mahri officers who had been brought for training to the Saudi city of Taif three months earlier. However, local Mahri security forces prevented the Saudis from taking control of the airport since they had not coordinated their arrival with the local authority, security apparatuses or President Hadi.[41] The standoff drew the intervention of local tribal sheikhs, who sent gunmen to back up the local security forces. Sultan Afrar then stepped in and attempted to mediate between the coalition and local Mahri forces. On November 14, Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar ordered that the Saudi forces be allowed to enter, but the Mahris refused to give way without approval from the local authority.

To determine al-Mahra’s collective position regarding the Saudi troops, a meeting was held between representatives of the local authority, the governorate’s security committee, the General Council and the tribes. On November 15, the gathering articulated six conditions to permit the deployment of Saudi forces, chief among them that the airport not be turned into a military base and the need for coordination between Saudi forces and the local authority.[42] After acceding to the demands, the Saudi forces were permitted to assume control of the airport.

After encountering opposition to their initial deployment, Saudi Arabia moved to exert control over al-Mahra’s local authority by engineering the removal of the governor. On November 27, Bin Kuddah was replaced by presidential decree and appointed to the largely ceremonial post of minister of state in the Yemeni government. Hadi later told a group of Mahri leaders that he was happy with Bin Kuddah’s leadership, particularly after he resisted enticement by the STC, and that his removal came after pressure from Saudi Arabia. According to a local Mahri official who later met with Hadi in Aden, the president said Riyadh had threatened to halt financial support until he agreed to appoint the Saudi’s chosen candidate, Rajeh Bakrit, as governor.[43]

The new governor arrived at al-Ghaydah airport on January 1, 2018, via a Saudi plane, accompanied by Mahri sheikhs who had been granted Saudi residency during the 1980s. Bakrit’s only previously known experience within the governorate was as a teacher with the Ministry of Education until 2000. He later lived in Riyadh, as well as the UAE and Qatar, before returning to al-Mahra to assume the post of governor.[44]

Between the dismissal of Bin Kuddah and arrival of Bakrit, Saudi Arabia quickly intensified its military build up in the governorate. Flights between Riyadh and al-Ghaydah increased, as did the overall presence of Saudi soldiers deployed at the airport.[45] Saudi forces also took control of Nishtun port along al-Mahra’s coast, along with the Shahin and Sarfait border crossings with Oman. Additional security procedures were put in place at the Shahin crossing, including the installation of an x-ray scanning device to inspect cargo entering Yemen. Saudi forces also restricted the entry of cargo to only when they were present at the port and border crossings.[46][47] This caused locals to complain about slowdowns in the import of goods and demand that the entry points be returned to the control of the local authority. Mahri tribal leaders also increasingly expressed concern about how the militarization of the governorate would affect al-Mahra’s social peace, cohesion and identity, particularly after reports emerged that Saudi Arabia was distributing weapons to certain tribes as part of efforts to combat smuggling.[48]

Mahri tribesmen, flying both the Yemeni and old al-Mahra flags, prepare for a protest in the Touf area of Hat district against the Saudi military presence in al-Mahra, September 24, 2018.

Mahri tribesmen, flying both the Yemeni and old al-Mahra flags, prepare for a protest in the Touf area of Hat district against the Saudi military presence in al-Mahra, September 24, 2018.

Salafist Arrivals Spark Local Opposition

A flashpoint against Saudi influence in al-Mahra and new governor Bakrit occurred in early January 2018 in Qishn, the historical capital of the Afrar sultans. During the first week of 2018, hundreds of Salafists, according to local estimates, who had been displaced from other areas of Yemen arrived in the town and based themselves around the al-Furqan Mosque. This influx represented a sizeable demographic shift for the district of roughly 30,000 people. The number of Salafists living in Qishn before January 2018 did not exceed three households.[49] A local Salafist named Abdullah Mohammed Al-Muhari – who had spent time at the prominent Salafist madrasa Dar al-Hadith in Dammaj, Saada governorate, and had developed connections to imam Yahya al-Hajuri, a Salafist scholar who managed the madrasa – then donated a large plot of land next to the Furqan Mosque to benefit the displaced Salafists. The site became a camp for many of these IDPs and soon a rumor began to circulate that a Salafist center, financed by Saudi Arabia, would be built in the town.[50]

In the eyes of locals, these rumors were confirmed when construction on a new building began next to the Furqan Mosque. On January 5, Bakrit visited the district, accompanied by a group of Saudi military officers. The governor and his entourage met with the Salafists and promised to provide aid relief, while food baskets were also distributed by the King Salman Center for Relief and Humanitarian Action.[51] As a result, local residents believed that Saudi Arabia was orchestrating a campaign to change the social fabric of the area. In general, Mahris adhere to a relatively moderate version of Sunni Islam and reject ultra-conservative ideologies such as Salafism. For instance, it is common for women to host men in the same room in al-Mahra. Such ideological differences provided a major impetus to the start of an impromptu protest against the Salafist influx.

The Qishn protest against the construction of the Salafist center was organized by a local English teacher named Fatima Saiid Sa’dan, sister of former deputy governor Saiid Sa’dan. Fatima began by authoring an appeal calling for the mobilization of women in the district against the Salafist presence and distributing it via WhatsApp. The call was met with support, exceeding 100 women on the first day.[52] On January 7, the women marched from Sa’dan’s school to the local administration. There they read a statement demanding that the local authority prevent the building of the Salafist center. The director general of the local authority in Qishn appeared before the crowd and promised to take care of the matter. He ordered a temporary halt of construction activity near the mosque and sent a message about the situation to Bakrit, but the governor did not respond to his communique that day. He also asked the protesters to form a committee to represent their demands, and Sa’dan was chosen as a member.

The committee then met on January 8 with local officials and tribal sheikhs, and demanded to meet personally with Bakrit to issue their demands. The same day, when the women’s committee learned that Bakrit was visiting al-Masilah district, about 130 kilometers from Qishn, members issued another call via WhatsApp to rally on the road on which the governor would pass back to al-Ghaydah.[53] Hundreds of protesters then gathered on the road and blocked the governor’s convoy. Faced with the opposition, Bakrit and Saudi officials agreed to meet with the women’s committee and local sheikhs from the district. The next day, while Bakrit was visiting the neighboring Huswain district, residents also demonstrated against the Salafists and insulted the new governor, referring to him as “a fraud.”[54]

During the meeting between the Qishn committee and the governor on January 14, Bakrit promised to resolve the problem while the Saudi delegation denied being behind the influx of Salafists or the plans to build a Salafist center.[55] After a declaration from the governor that no Salafist center would be built, many of the Salafists decamped Qishn for other parts of al-Mahra, including al-Ghaydah and Huswain district. However, the Salafists continue to travel to Qishn and gather at Furqan Mosque for Friday prayers.[56]

Saudi Military Buildup Continues

By March 2018, Saudi forces had converted al-Ghaydah airport into a military base. This was in contravention to one of the primary conditions set by the local authority to allow the initial Saudi deployment in November 2017. As of this writing, the base houses a central operation command that collects intelligence, organizes missions and oversees the six major Saudi military camps in the governorate, which in turn coordinate among smaller military outposts. Reinforcements, machinery and weaponry also continue to arrive in al-Mahra via the airport. New security measures were added at the facility, which restrict access even to Yemeni government and security officials, and civilian flights have been canceled.[57] A military base was also established at Nishtun port in early 2018. In January that year, a Saudi warship arrived at the port and offloaded troops with medium and heavy weaponry. In total, an estimated 1,500-2,000 Saudi troops are deployed throughout the governorate.[58] In addition to al-Ghaydah and Nishtun port, major bases have been established in Hat district, Lusick in Hawf district, Jawdah in Huswain district, and Darfat in Sayhut district.

To complement its troop deployment, Riyadh also began employing Yemeni proxies as security forces in al-Mahra. The most infamous unit, known locally as the Quick Response Forces, was a battalion of masked soldiers that dressed all in black and drove around in black SUVs in a manner similar to counterterrorism forces. Members of the unit hailed from the southern governorates of Abyan, al-Dhalea, Lahj and Aden, and were reportedly veterans of the 2015 Battle of Aden between Yemeni government forces and the armed Houthi movement. Nasser Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, President Hadi’s son, later recruited the troops to deploy to al-Mahra and be placed under the control of Governor Bakrit. The unit, headquartered at the Presidential Palace in al-Ghaydah, was not under the local security forces’ chain of command, despite receiving salaries from the governorate’s budget.[59] Due to the local perception of the force being the instrument that Saudi Arabia employed, via the governor, to crack down on local resistance, residents began to refer to them as The Security Belt of al-Mahra, an allusion to UAE-backed militias operating Aden, Lahj, and Abyan governorates.[60] However, the Quick Response Force was later sidelined without explanation in mid-2018 after the arrival of other Yemeni forces recruited from southern governorates.

To build its proxy force in al-Mahra, Saudi military officials mainly recruited Yemenis from Lahj, Abyan, and al-Dhalea governorates. Like the Quick Response Force before them, these militias are technically illegal since they exist outside the records and control of al-Mahra’s local authority. There is no reliable figure on their total number, but they are estimated to constitute several battalions, numbering in the thousands of fighters. Many of these troops receive salaries in Saudi rials and are led by Yemeni officers under the command of Saudi military officials.[61] The Yemeni proxy forces are deployed around Saudi military bases and at small outposts around the governorate, including along al-Mahra’s long coastline, which has led some units to be referred to as the “Coast Guard.”

From their main base at al-Ghaydah airport, Saudi forces began to assume a role akin to a state security apparatus in al-Mahra. Air reconnaissance and other operations are launched from a command center at the base, bypassing the local authority. “You seem to want to visit the airport” emerged as a joke among Mahris when discussing the war, politics or Saudi Arabia, in reference to local speculation that the facility houses a secret prison. The opacity and anxiety surrounding the Saudi-backed operations in the governorate made locals wary about voicing any criticism of Saudi Arabia during the first half of 2018.

Opposition to Riyadh Mobilizes in Al-Mahra

The official protest movement against the Saudi presence in the governorate began after Sultan Afrar returned in May 2018 from Muscat. Al-Afrar had been mainly based in the Omani capital since leaving Saudi Arabia in 2017, traveling on occasion to al-Mahra and Socotra. As was the case during Emirati attempts to expand influence in al-Mahra, Oman viewed the Saudi military presence in the governorate, particularly its seizure of border crossings with the sultanate, as a challenge to its traditional influence. Preparations for Sultan Afrar’s return were organized by al-Mahra Governorate Deputy for Desert Affairs Ali al-Hurayzi, along with a number of sheikhs who had attempted in November 2017 to prevent the deployment of Saudi forces at al-Ghaydah airport. When the Saudis learned of the preparations, a commander of the Saudi forces in al-Mahra, known locally as Abu Sultan, threatened a local tribal leader, Sheikh Aboud Bin Haboud al-Muhari, saying he would personally bear the consequences if Sultan Afrar was received by more than five cars and a large crowd. The sheikh replied that the Mahris would greet al-Afrar with 500 vehicles.[62] When al-Afrar arrived in Yemen via the Shahin border crossing on May 6, 2018, the crowd greeting his convoy was estimated to be in the thousands.[63]

Upon his arrival, al-Afrar gave a speech to the crowd in which he demanded the departure of all Saudi forces from al-Mahra, in addition to Emirati forces from Socotra Island.[64] This represented the first public statement against the Saudi presence in al-Mahra. Given his prominence in al-Mahra, Riyadh could not challenge al-Afrar in the same manner as its other opponents in the governorate. Even Governor Bakrit had to defer to al-Afrar, setting up a banquet the day after the sultan’s arrival that included members of the local authority as well as Saudi officers and tribal leaders. At the event, the sultan reiterated his call for the Saudis to leave al-Mahra.

The return of Sultan Afrar encouraged Mahris who were disgruntled with Saudi Arabia to begin speaking out publicly against its military deployment and attempts to subvert the local authority. On May 9, 2018, locals, after escorting the sultan to his home al-Ghaydah, began a sit-in to demand the departure of Saudi forces. Al-Afrar’s home was chosen as the location of the protest because Mahri demonstrators saw the sultan as a unifying figure who could represent their demands to the authorities. A local committee was then set up to manage the protesters and communicate their demands.[65] However, the protest did not receive substantial media attention as it was launched in the lead-up to the month of Ramadan.

On the first day of Ramadan, two weeks after the sit-in began, organizers submitted six demands on behalf of the organizing committee to Sultan Afrar, then dissolved the protest. The demands included: 1) The reinstatement of local authority management and procedures at Shahin and Sarfait border crossings and Nishtun port under Saudi supervision; 2) Fully empowering the local authority to make governance decisions in al-Mahra; 3) The transfer of Saudi proxy forces and those under the authority of the governor to the chain of command of the local authority; 4) The return of al-Ghaydah airport to civilian control; 5) The replacement of current security personnel at Sarfait and Shahin border crossings and Nishtun port and the return of the port’s control to local forces; and 6) Saudi non-interference in the functioning of border crossings and Nishtun port.[66] Al-Afrar passed the list to both Saudi authorities and Bakrit, but received no immediate response. The sit-in also served to open the door to public criticism of Saudi Arabia and the emergence of an open protest movement against the presence of Saudi forces in al-Mahra.

As Riyadh continued its military expansion and ignored calls for it to leave al-Mahra, a second sit-in was organized in al-Ghaydah on June 25, 2018. Unlike the first protest, this second gathering was organized well in advance and included a greater presence of women and local media. It also was bolder in its opposition, with demonstrators and leaders directly attacking both Bakrit and Saudi Arabia. The same six demands issued during the first sit-in were reiterated. The second protest also was notable for the emergence of al-Hurayzi, then-governorate deputy for desert affairs, as the opposition’s main leader alongside Sultan Afrar.

Ali al-Hurayzi one of the main public figures in al-Mahra opposing the Saudi presence in the governorate. Pictured here on October 2, 2018.

Ali al-Hurayzi one of the main public figures in al-Mahra opposing the Saudi presence in the governorate. Pictured here on October 2, 2018.

Ali al-Hurayzi is a unique political figure in al-Mahra. He was appointed commander of the border guards along the al-Mahra-Omani border in 1997, and in 2009 also assumed his desert affairs post. al-Hurayzi does not hold inherent authority as a sultan or tribal sheikh. However, he has been able to harness popular discontent and leverage his strong local Mahri character.[67] al-Hurayzi is also unbound by the tribal political considerations of Sultan Afrar who, as a unifying figure representing the tribal sheikhs of al-Mahra and Socotra, is careful not alienate any party, including pro-Saudi sheikhs. This allows al-Hurayzii to be more bold and aggressive in his statements. For instance, he will refer to the “Saudi occupation” of al-Mahra while Afrar strikes a more conciliatory tone, saying our “brothers from Saudi Arabia.”

Even before the return of al-Afrar to al-Mahra in May 2018, al-Hurayzi attempted to fend off attempts by outsiders to establish influence in the governorate. Carrying out the orders of then-governor Bin Kuddah, al-Hurayzi prevented the STC head al-Zubaidi from entering al-Mahra with a convoy of armed men ahead of the inauguration of the STC’s branch office in the governorate in October 2017.[68] He was also an early critic of the Saudi military deployment in al-Mahra. After the arrival of Saudi forces at the airport, al-Hurayzi told the General Council of the People of al-Mahra and Socotra that the Saudi presence threatened the social fabric of al-Mahra and that the best way to promote security in the governorate was not via foreign military forces but by supporting the local security services. Notably, al-Hurayzi also brokered a deal – via mediators – with al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) after the group’s takeover of the city of Mukalla in neighboring Hadramawt governorate in 2015. As part of the arrangement, AQAP would not carry out any operations in al-Mahra, and in return, Mahri security forces would not arrest AQAP militants.[69]

Al-Hurayzi has close ties with both Sultan Afrar and Oman. Al-Hurayzi publicly acknowledges the direct support provided to him by the Omani government. Muscat has arranged meetings in the Omani capital between al-Hurayzi and international ambassadors, European and American officials, and representatives from international organizations, allowing him to communicate the local viewpoint on the opposition movement with international actors. Al-Hurayzi also managed to organize the entry of Western journalists into al-Mahra via the border crossing between Oman and Yemen without visas or entry/exit stamps.[70]

Al-Hurayzi has been dogged by allegations of involvement in smuggling in the governorate since he became commander of the border guards in al-Mahra. At one point, then-President Saleh ordered his arrest and interrogation on charges of smuggling. Al-Hurayzi was detained for 24 days before being released.[71] Saudi Arabia has recently revived these rumors, with Al-Arabiya and other Saudi media outlets repeatedly accused him of being a smuggler and colluding with the Houthis.[72]

Mahris Divided Over Saudi Presence

The Saudi military presence and the resultant opposition movement has led to an unprecedented political divide in al-Mahra. Within the local authority and the General Council, there are both supporters and opponents of the Saudi presence. Sultan Afrar has only voiced his opposition to the Saudi military as a private citizen, and not in any official statement as chairman of the General Council, in order to preserve the neutrality of the body and not alienate members aligned with Saudi Arabia. However, despite the divided opinion in al-Mahra, the Saudi issue has thus far not lead to open internal conflict. This can be partly attributed to local tribal customs and traditions, which emphasize the unity of the Mahri people and the peaceful settlement of disputes.

In response to the initial sit-in after the return of Sultan Afrar, Bakrit and several pro-Saudi sheikhs issued a statement supporting the coalition and rejecting the protests. Firing back, other members of the local authority began to attack the governor directly during the second sit-in, including al-Hurayzi, who characterized Bakrit as “disreputable.”[73] Qahtan, the General Security director at the time, later mediated between the protest organizing committee and the commander of Saudi forces, and on July 13, 2018, an agreement was reached. The commander of Saudi forces in al-Mahra, Abdel Aziz al-Sharif, signed an agreement to implement the protesters’ six demands within two months, and the sit-in was suspended.[74] However, the next day President Hadi issued a decree that removed al-Hurayzi and Qahtan from their positions within the local authority. Rather than neutering the protest movement, al-Hurayzi’s removal increased his notoriety and allowed him to engage with the media free from official restrictions on his speech. It was after his firing that al-Hurayzi began to characterize the Saudi presence as an occupation, and he has even threatened the use of force against Saudi troops.[75]

Despite signing the agreement to end the sit-in, none of the six demands were implemented. Rather, additional forces were brought into the country and new military camps were established. This included the construction of several small military outposts for their Yemeni proxy “Coast Guard” force along the coastline from al-Masilah district in the west to Hawf district in the east. Saudi officers also continued to import fighters from other southern governorates.[76] In reaction, the protest organizing committee issued a statement in September 2018 directed at the governorates of Lahj, Abyan, and al-Dhalea, calling on them to stop sending their children to al-Mahra in service of Saudi Arabia.[77] As of September 2018, more than 16 military positions existed in the districts of al-Masilah, Sayhut, Qishn and Huswain. The building of these camps provoked local resentment, with residents staging protests similar to the demonstrations against the Salafists in Qishn. Opposition to the military outposts mainly stemmed from their proximity to residential areas as well as common grazing areas and fishing grounds.[78]

Protests continued after the sit-in ended in al-Ghaydah in June. Other expressions of opposition took the form of vigils and festivals near Saudi military sites, particularly those that encroached on local fishing or animal grazing areas. These events often included speeches, the reading of poetry and the playing of patriotic music. Through such efforts, Mahri residents managed to prevent the construction of several military outposts.[79] In August 2018 in the town of Itab, along the coast in Sayhut district, locals held a demonstration to prevent a contractor from erecting a military encampment. The Saudis reached out to the director general of the district, Sheikh Muhammad Ali al-Zuwaidi, to intervene, even though he did not know about the Saudis’ plans in his district until residents complained. Al-Zuwaidi came to the site to convince people of the benefits of the camp, but he was strongly criticized and later gave up.[80]

Escalating Tensions and Direct Confrontations

One of the most notable confrontations since the Saudi deployment in al-Mahra occurred in September 2018, when a Saudi engineering team began to demarcate an asphalt road near the border area around Kharkhir in northeast Yemen.[81] This project had not been made public previously. President Hadi, during a visit to al-Mahra on August 1, 2018 – where, in a sign of negative local perceptions, he was received by the Saudi Ambassador to Yemen rather than by local Mahri officials – announced $670 million in projects proposed by the Yemen Reconstruction Program.[82] This included plans to build a teaching hospital, a university and a power station in the governorate.

When word spread about the engineering team laying the ground for a paved road, many residents viewed the project as the first step in Saudi Arabia reviving its longstanding desire to build an oil pipeline through the governorate. A memo had been leaked in the previous month in which the Saudi company Huta Marine Works, part of the Bin Laden Group, thanked the Saudi Ambassador to Yemen and Chairman of the Yemen Reconstruction Program for his confidence in commissioning the company to submit a feasibility study to build an oil port. Although the memo did not explicitly mention al-Mahra, it was used as evidence of Saudi intentions by local and regional media.[83]

A letter published by the Mahra Post, which would appear to show the Huta Marine Works company thanking the Saudi ambassador to Yemen for asking for a proposal for a feasibility study to build an oil port, dated August 13, 2018.

A letter published by the Mahra Post, which would appear to show the Huta Marine Works company thanking the Saudi ambassador to Yemen for asking for a proposal for a feasibility study to build an oil port, dated August 13, 2018.

On September 17, 2018, the 11th Infantry Brigade under Yemeni government command stopped the Saudi engineering team from continuing work on the road. The decision was taken by the brigade commander since he had received no prior warning or order regarding the construction activity. The next day, the engineering team returned after Hadi’s office contacted the brigade commander and ordered him to allow the work to proceed. However, local tribes, most notably the sheikhs of Samouda who are loyalists to al-Hurayzi, stepped in, expelling the engineering team across the border and ripping up concrete markers. Dismayed, the Saudis then ordered the 11th Infantry Brigade to protect the engineering team, but the brigade commander refused to confront the local tribes. A tense standoff occurred after the Saudis rallied their own loyalist sheikhs in al-Ghaydah and deployed more than 30 military vehicles and more than 100 troops[84] to the house of Sheikh Salim bin Sharaf, who was requested to travel with Governor Bakrit to confront the Samouda tribes. All troops eventually returned to their barracks after Bin Sharaf promised to resolve the issue peacefully by speaking with al-Hurayzi.[85]

Tensions were further escalated a week later when the coalition issued an arrest warrant for al-Hurayzi. On September 25, Al-Jazeera leaked the arrest order against al-Hurayzi, which was issued by the Joint Operations Command center in Hadramawt governorate, an operational command facility operated by Saudi, Emirati and Yemeni forces. The order was sent to a Yemeni army field commander in al-Ghaydah, Brigadier Abdullah Mansour, an old friend of al-Hurayzi. The memo ordered the arrest of al-Hurayzi and his security detail on charges of tarnishing the image of the coalition by inciting protests and destabilizing security, and hindering Saudi-led development in Yemen by preventing the engineering team from working on a survey of the Kharkhir road. The memo also banned any future demonstrations against the coalition.[86]

There was widespread reaction to the arrest warrant, with numerous sheikhs, local dignitaries and the general public showing solidarity with al-Hurayzi. Even the General Council, which had refused to back the protests, issued a statement denouncing the arrest order and warning against undermining al-Mahra’s “political symbols”.[87] When the arrest warrant became public, al-Hurayzi was in Shahin, intending to travel the next day to Oman. However, he changed his destination to al-Ghaydah and the next morning entered the city in a convoy of more than 150 cars, in clear defiance of the arrest order.[88] Coalition official Colonel Turki al-Maliki later appeared on Al-Arabiya television to deny an arrest warrant had been issued.[89]

In the aftermath of the aborted arrest attempt, Oman began allowing Mahri opposition figures to give statements to the media from Omani territory. During a television interview in October 2018 with the Al-Jazeera correspondent in Muscat, al-Hurayzi attacked Saudi Arabia and described it as an occupation force.[90] General Qahtan was also interviewed by Al-Jazeera in Muscat in January 2019, where he discussed the opposition movement and accused the Saudis of “terrorism” in al-Mahra.[91]

The attempted arrest of al-Hurayzi appeared to be part of efforts to eliminate opposition to the coalition’s presence in al-Mahra. This campaign began with the pressure on President Hadi to dismiss governor Bin Kuddah in November 2017, and was followed by the replacement of al-Hurayzi and Qahtan in June 2018. Ali bin Abdullah bin Afrar, the director of the Ministry of Human Rights’ al-Mahra branch – and a loyalist of al-Hurayzi – was also sacked in January 2019.

Standoffs Between Saudi-backed Forces and Mahri Tribes Turn Violent

Despite growing tensions between the coalition and Mahri locals, the governorate had managed to avoid a violent confrontation until an incident in al-Anfaq on November 14, 2018. Locals had gathered in the village in Huswain district near Nishtun port to protest the establishment of a military outpost along the road linking al-Anfaq to al-Ghaydah. In response to the demonstration, the Saudi-backed Coast Guard deployed dozens of soldiers. Responding to the deployment, more locals gathered, some carrying weapons. Negotiations were underway to diffuse the situation when clashes broke out between the two groups around 10 p.m. A firefight continued for several hours, during which two protesters were killed, until all parties withdrew.[92]

Following the clashes, many locals feared al-Mahra would experience the chaos and destruction it had managed to avoid thus far during the conflict. A tweet by Governor Bakrit in reaction to the clashes, saying that the local authority was facing smuggler gangs and outlaws and would respond with an iron fist, only provoked further outrage.[93] The tweet was interpreted by some as a declaration of war between supporters of Saudi Arabia and its opponents. In response to the incident, the General Council met and unanimously condemned the killings and the characterization of protesters as terrorists and smugglers, and demanded the handover of the killers for trial. It also called on the media to cease incitement over fears that the situation could further escalate.[94] Also in an apparent effort to ease tensions, Bakrit later tweeted that he had declared the formation of a committee to investigate the incident.[95]

Opposition to the Saudi presence in al-Mahra turned violent again on March 11, 2019. Clashes between tribesmen and Saudi-backed Yemeni forces near the Shahin border crossing with Oman resulted in the wounding of two tribesmen and an unknown number of coalition casualties.[96] The incident was sparked after locals intercepted vehicles belonging to the Saudi coalition between Shahin and Hat districts; the resulting clashes closed the Omani border for a full day. A presidential committee, chaired by head of the Yemeni General Staff Lieutenant General Abdullah al-Nakh’ee, Deputy Minister of Interior Maj. General Ahmed al-Musawa, and Vice-Chairman of the Military Intelligence and Reconnaissance Brigade Hussein Omran, was then tasked to mediate. However, the committee failed to reach any formal agreement to calm tensions. Meanwhile, the General Council of the People of al-Mahra and Socotra held a session, chaired by Sultan Afrar, after which it called on all tribes and other parties to refrain from further violence and engage in dialogue. The body also reaffirmed its support for the legitimate Yemeni government and “the Arab Coalition led by Saudi Arabia in accordance with the stated objectives.”[97]

Saudi Military Directly Intervenes in Al-Mahra Tensions

On April 19, 2019, in another significant escalation in the dispute between Saudi Arabia and al-Mahra locals, Saudi Apache attack helicopters bombed a police checkpoint. This marked the first occasion that the Saudi air force was employed in the growing tensions in al-Mahra, conducting airstrikes in a location at least 500 kilometers from the nearest active frontline separating Houthi- and Yemeni government-controlled areas. Saudi-aligned media and outlets that grant a platform to the local opposition provided conflicting accounts of the incident.

Al-Mahra TV – a TV station established by Saudi Arabia in December 2018 and headquartered in Riyadh – reported that Bakrit had escaped assassination by “outlawed elements funded by foreign countries” near al-Labib checkpoint in Rumah district.[98] Though Rumah officially falls within Hadramawt governorate, Mahri tribes consider it to be part of al-Mahra. The governor had been returning to al-Mahra from preparations for the Yemeni parliament session in Sayoun, Hadramawt, when he was ambushed near the checkpoint. Apache aircraft flying in support of the convoy intervened and fired at the perimeter of the checkpoint, allowing the cars to pass.[99] Meanwhile, al-Hurayzi claimed to Al-Jazeera that a convoy of military vehicles full of militants surprised local tribesmen who served as a police force at the checkpoint. The tribesmen attempted to halt the convoy – which allegedly contained members of Saudi-backed militias in al-Mahra – but the cars refused to stop, precipitating the firefight and the intervention of the Saudi helicopters.[100]

The incident, which injured three members of the governor’s security entourage and a checkpoint guard, once again flared tensions in the governorate. Days later, a report emerged that Riyadh was pressuring the Yemeni government to issue an official decree to replace local forces at al-Labib checkpoint with a Saudi-allied militia. In response, local tribesmen sent reinforcements to the checkpoint.[101] Both sides continued to cling to their narratives about the event, with Bakrit refusing to issue a statement on the incident,[102] while the opposition ignored the assassination claims.[103]

Saudi aircraft intervened in another dispute on June 3, 2019, when Mahri tribesmen in Shahin district intercepted a Saudi-backed, Yemeni military unit heading to al-Ghaydah from the al-Khalidiya military camp in Hadramawt. After the tribesmen blocked the road and insisted that the troops return to Hadramawt, an Apache helicopter fired a warning shot near the local Mahri force, causing no material damage or casualties. The standoff ended with the proxy force turning back to Hadramawt.[104]

The recent use of Apache helicopters by the Saudi coalition in al-Mahra indicates a further step in the militarization of the simmering dispute in a governorate. The tactic of employing helicopters to intimidate the opposition to the Saudi presence in al-Mahra was actually first raised by Bakrit in June 2018, when the governor threatened to use Apache aircraft to strike those who obstructed the coalition’s work in al-Mahra.[105] However, at the time this was viewed largely as an empty threat, given that helicopters would not take off from al-Ghaydah airport without orders from Saudi officers. Bakrit himself later revealed his lack of authority to command the aircraft on Twitter when he appealed for helicopters to rescue him and others trapped by flooding after Hurricane Laban struck al-Mahra in October 2018.[106]

Mahris in the Tammoun area of Masilah district organized a protest festival to reject the Saudi military establishing a military base in their area, September 17, 2018.

Conclusion

In the 20 months since Saudi Arabia deployed military forces and established military bases in al-Mahra, it has become clear Riyadh is failing to diffuse opposition to its presence. Despite a pro-Saudi figure as governor, a Yemeni government beholden to Riyadh, and thousands of Saudi troops and allied Yemeni proxy forces deployed around the governorate, Saudi influence in al-Mahra appears to be increasingly challenged in the face of growing local opposition.

Riyadh’s efforts to quell the Mahri protest movement appear only to have emboldened those who oppose the coalition’s presence in al-Mahra. Fueled by a collective social dream of sovereignty – stemming from its long history as an independent region – and a local culture that emphasizes the unity of its people, some Mahri leaders and tribes have shown a consistent willingness to push back against the coalition’s attempts to establish influence in al-Mahra. In these efforts, Mahris have been backed by neighboring Oman, which does not want to cede influence to other regional countries in an area where it has long cultivated influence and that it views as being of strategic importance.

The Mahri opposition to the Saudi- and Emirati-led military coalition first became visible in 2015 soon after it intervened in the Yemen war. Local figures first moved to counter the UAE’s attempts to establish and command local military forces, seeing the move as a tactic to cement Emirati control in al-Mahra as had happened in other southern governorates. Later, in November 2017, locals attempted to block the initial Saudi military deployment in the region. Despite being unsuccessful in this regard, local opposition has proven capable in several cases of preventing the implementation of unpopular political decisions, the establishment of military outposts and the deployment of Saudi-backed Yemeni proxies.

In the past year, Mahri tribes have increasingly confronted what they perceive as encroachments on local sovereignty. Several recent confrontations have led to violence – including the al-Anfaq incident in November 2018, clashes near the Omani border in March 2019, and the shoot out at al-Labib checkpoint in April – threatening the prized stability that the governorate has thus far been able to maintain throughout the wider conflict in Yemen. Indeed, there have been recent calls for military resistance against the Saudi presence, with opposition leader al-Hurayzi declaring his intention to establish local militias, although no practical steps such as the establishment of training camps have yet been taken.[107]

Even the internationally recognized Yemeni government has recently begun pushing back against the coalition’s presence in al-Mahra. “The Yemeni government wanted our allies in the coalition to march with us north, not east,” Interior Minister Ahmed al-Misri said on May 5, 2019, referring to the coalition deployment in al-Mahra. He added that the partnership between the Hadi government and the coalition was intended to combat the armed Houthi movement, not manage “liberated” areas. The public statement marked a rare rebuke of the military coalition by a government that has mostly proven unwilling or unable to stand up Riyadh and Abu Dhabi.[108]

However, Saudi Arabia and its Emirati ally have yet to indicate any willingness to abandon their ambitions in al-Mahra. The governorate remains an area of strategic security importance in the broader conflict in the country, as a purported avenue for arms smuggling to the armed Houthi movement. There are also signs that the UAE is seeking to make a renewed push at influence in the governorate with recent reports that its local ally, the STC, is trying to establish a unit of the Elite Forces in al-Mahra.[109] Furthermore, the arrest of Qatari military officer in al-Mahra in May 2018 indicates that Doha may also have some interest in the governorate. Yemeni government troops detained Mohsen al-Karbi, a Qatari intelligence officer as he was attempting to leave Yemen to Oman, and accused him of coordinating with the Houthi movement, though Qatar refuted the allegations, saying he was in al-Mahra on a personal trip to visit relatives.[110]

Despite the escalating tension between Saudi Arabia and the Omani-backed opposition, it is not in the interest of any party to see al-Mahra spiral into chaos. After managing to mostly avoid the degree of upheaval the rest of Yemen has experienced, the emergence of open conflict with external powers backing rival sides (as is visible in many other parts of the country) would represent a dramatic setback. Saudi Arabia in particular seems likely to continue efforts to cement influence in al-Mahra and undercut local opposition to its presence, but the situation remains too volatile to be sure it can manage this with enough restraint to avoid an escalation of armed violence. In an environment of growing militarization and polarization – where peaceful protests have devolved into gunfights, threats of iron-fist measures and fears of chaos – the potential even for unintended escalation cannot be underestimated.

Edited by: Ryan Bailey is an editor and researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover diplomatic, political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Endnotes

- In 2005, the Yemeni government declared the forest region around al-Mahra’s Hawf district to be a natural reserve because of its unique climate and ecological diversity. The region is blanketed with fog from July to September every year and provides an important habitat for many species of birds, animals and tropical plants.

- “2017 Population Projections by Governorate and District,” The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, https://data.humdata.org/dataset/yemen-cso-2017-population-projections-by-governorate-district-sex-age-disaggregated; and Elisabeth Kendall, “The Mobilization of Yemen’s Eastern Tribes: Al-Mahra’s Self-Organization Model,” in Marie Christine-Heinze (ed) “Yemen and the Search for Stability Power, Politics and Society After the Arab Spring,” I.B. Taurus, 2018. p. 77.

- “Profile of al-Mahra Governorate,” National Information Center, http://www.yemen-nic.info/gover/alal-Mahraa/brife/.

- Ahmed Nagi, “Oman’s Boiling Yemeni Border,” Carnegie Middle East Center, March 22, 2019, https://carnegie-mec.org/2019/03/22/oman-s-boiling-yemeni-border-pub-78668.

- “Mahra Sultanate,” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/place/al-Mahra-Sultanate.

- Elisabeth Kendall, “The Mobilization of Yemen’s Eastern Tribes: Al-Mahra’s Self-Organization Model,” in Marie Chrstine Heinze (ed) “Yemen and the Search for Stability Power, Politics and Society After the Arab Spring,” I.B. Taurus, 2018. p. 73

- Al-Mahra served as a rear base for the Dhofari rebels, as well as a source of military supplies and support, provided by Marxist South Yemen and other communist countries such as the Soviet Union and China. Sultan Qaboos, after assuming the throne in 1970, pursued a dual strategy of defeating the insurgency with support from the British and other conservative Gulf monarchies and reaching out to rebel leaders. The rebellion ended with a general amnesty and national reconciliation, and lasting peace was established in Dhofar.

- 2018 memoir of former president of South Yemen Ali Nasser Mohammed, “Memory of a Homeland.”

- “Factbox: the Strait of Hormuz- the world’s most important oil artery,” Reuters, June 13, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-saudi-oil-emirates-tanker-factbox/factbox-strait-of-hormuz-the-worlds-most-important-oil-artery-idUSKCN1TE1PS.

- Interview with South Yemen President Ali Nasser Mohammed in October 2017.

- Interview with Ali al-Hurayzi, protest leader and former governorate deputy for desert affairs, February 6, 2019. Al-Hurayzi discussed the Saudi pipeline proposal with then-President Saleh in al-Hurayzi’s capacity at the time of border guard commander for al-Mahra.

- “Tribesmen Clash With Saudi Troops in al-Mahra” in The Yemen Review, February 2019, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7269#Tribesmen-Clash-With-Saudi-Troops-in-al-Mahra.

- The Yemen Review: March 2019, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, April 8, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7269.

- “Sons of al-Mahra declare their rejection of the eastern region and consider it a consecration of the policy of the Hadrami league,” Akbar al-Youm, August 27, 2013, http://akhbralyom-ye.net/news_details.php?lng=arabic&sid=70423.

- “Al-Mahra Sultan: Hadramawt region does not concern us and there is no backing down from our choice as an independent region,” Hour News, February 28, 2014, https://hournews.net/news-27596.htm.

- Yemen crisis: Rebel actions ‘illegitimate’, says ex-president,” BBC, February 22, 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-31564933.

- Statement of the General Council of the People of Al-Mahra and Socotra Governorates issued on April 14, 2015, rejecting the coup and assuring the legitimacy of President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi and operation Decisive Storm,” Yemen Now, April 14, 2015, http://yemen-now.com/news568158.html.

- Mansour Rageh, Amal Nasser and Farea Al-Muslimi, “Yemen Without a Functioning Central Bank: The Loss of Basic Economic Stabilization and Accelerating Famine,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 2, 2016, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/55.

- Interview with former governor Mohammed Bin Kuddah, February 6, 2019.

- Peter Salisbury, “Yemen: National Chaos, Local Order,” Chatham House, December 2017, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2017-12-20-yemen-national-chaos-local-order-salisbury2.pdf.

- Interview with former governor Mohammed Bin Kuddah, February 6, 2019, and with former Director of General Security of al-Mahra Governorate Ahmed Mohammed Qahtan, March 5, 2019.

- Bin Kuddah previously held the position of governor of al-Mahra twice before (1990-91, 1992-94). This experience helped him in restoring the power of the local authority. Bin Kuddah also has a strong relationship with Oman, where he was a political refugee following the 1994 civil war. As governor of al-Mahra at the time, geography forced him to support the failed southern bid for secession, even though he was appointed to his position by then-president Saleh. After the collapse of southern forces, Bin Kuddah fled to Oman, where he remained for three years until receiving a pardon from Saleh.

- Interview with former governor Mohammed Bin Kuddah, February 6, 2019.

- Interview with senior official from the Central Bank of Yemen, June 25, 2019

- Interview with former Director of General Security of al-Mahra Governorate Ahmed Mohammed Qahtan, March 5, 2019.

- Interview with former governor Mohammed Bin Kuddah, February 6, 2019.

- “Oman uncovers ‘spy network’ but UAE denies any link,” BBC, January 31, 2011, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-12320859.

- “Sultanate of Oman supports al-Mahra Yemen with 16 generators,” Yemen Monitor, December 13, 2016, http://www.yemenmonitor.com/Details/ArtMID/908/ArticleID/14353/mediaid/15476.

- Interview with former al-Mahra governor Mohammed Bin Kuddah, February 6, 2019, and with former Director of General Security of al-Mahra Governorate Ahmed Mohammed Qahtan, March 5, 2019.

- Shadiah Abdullah al-Jabry, “Federal challenge: Yemen’s turbulence may have opened a door for the return of the sultans,” The National, June 26, 2014, https://www.thenational.ae/world/federal-challenge-yemen-s-turbulence-may-have-opened-a-door-for-the-return-of-the-sultans-1.564399.