The Old City of Sana’a has been inhabited for over 2,500 years; it boasts unique architecture – those distinctive multistory towers with delicate white-trim designs – and UNESCO world heritage status.[1] Today, this built heritage, and the human history it evinces, face multiple threats. Heavy rains have recently caused damage to around 1,000 houses, starkly exposing the city’s precarious situation and the extent of the problems in the service sector. These issues present a major challenge to the preservation of the Old City, but they also raise questions about the role of the General Organization for the Preservation of the Historic Cities of Yemen. The GOPHCY is the primary party in charge of preserving Yemen’s historic cities, according to Law No.16 of 2013.

This article will outline the history of the Old City of Sana’a and the most pressing challenges facing the city, and it will detail the role of the GOPHCY in preserving the city – examining that organization’s current work and its operational challenges.

Historical Overview of the Old City of Sana’a

The history of the Old City of Sana’a is threaded through with mystery, legends and divergent accounts. Evidence of early human activity in the area, based on archaeological research, has been dated back 1.6 million years, to the Paleolithic period. Some say construction of the city itself began with Shem, the son of Noah,[2] although no historical data confirms this narrative.[3] Still other sources suggest that Sana’a is a Sheban city, built by Halk Amr, king of Sheba and Dhu Raydan, in the years 140-150 of the Sheban calendar, or 1070-1080 BC.[4] UNESCO, however, dates the city’s founding to just a little over 2,500 years ago.[5]

Sana’a city is situated 2,350 meters above sea level, in a mountain valley at the center of a plateau that extends from the areas of Nuqum, in the east, to Ayban, in the west; and from Naqil Yaslah, in the south, to Shibam al-Firas, in the north.[6] Its strategic location, allowing control of trade routes between the kingdom of Sheba, in Marib, and the city of Tihama, on the Red Sea Coast, helped it prosper in the second millennium BC.[7] By the second century BC, Sana’a had become established as a seat of power in the region and went on to be the capital of Yemen’s ancient kingdoms.

Conflict between states in the area that became modern-day Yemen broke out during the era of the Abbasid Caliphate (which spanned from roughly 750-1250 AD), and Sana’a was a prize desired by many.[8] For the Ziyadid dynasty (819-1018), the city of Sana’a represented a launching pad to control all of Yemen, while the Rasulid dynasty (1229-1454)viewed the city as a crucial strategic camp for its soldiers.[9] The Ya’furid dynasty, which had broke away from the Abbasid Caliphate, emerged triumphant from a series of battles with Ziyadid forces in 819 AD. With Sana’a as its capital, its jurisdiction extended across Yemen to Hadramawt, with its rule lasting until roughly 1000 AD.[10]

The Three Phases of Old City Construction

First phase: The Pre-Islamic period (910 BC – 525 AD). In the first century BC, the Ghamdan Palace was built.[11] The palace was the main reason the Old City of Sana’a prospered, consolidated and expanded from its origin as scattered villages. A wall of clay was built around the city sometime between 115 and 80 BC, with four main entrances: Bab al-Yemen, Bab Shaoub, Bab al-Sabah and Bab Satran. Subsequently, the Al-Qalis Church was built. These monuments, as well as the city’s souk (market) constituted Sana’a’s most important landmarks during this period.[12]

Second period: The Islamic era (627 AD-1229 AD). Building resumed and Sana’a continued to expand during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods.[13] In 6 hijri (627 AD), the Great Mosque was built. A cemetery, Musalla al-Eid, was built in 998 AD north of the Old City and soon surrounded by houses.[14] The city prospered during the days of Caliph Haroun al-Rashid, its borders reaching the stream of Al-Saila and encompassing 70,000 houses.[15] In 525 hijri (1131 AD), the Sulayhid dynasty built the east wing of the Great Mosque, restored the city walls and added seven entryways. The city expanded west during the Ayyubid era, in the 12th century AD, with the construction of Al-Nahryan neighborhood. Bustan al-Sultan, the ruler’s headquarters, was built on the southern side of Al-Nahryan.[16]

Third period: The Ottoman era (1547 AD -1629 AD). A new neighborhood, Bir al-Azab, was built on the western side of Sana’a, to be inhabited by employees of the Ottoman Empire.[17] The Ottomans built a wall around it, complete with towers, so that it resembled the walls of the original Old City. They expanded the palace fortress and built Al-Bukayriyah Mosque.[18] In the 17th century AD, the Jewish quarter was established in the area of Souq al-Sabha, currently Al-Sabah, outside the western portion of the Old City wall.[19] Since that time, other neighborhoods have been built to the east and west.

Today, the built heritage of the Old City of Sana’a is a material record of the city’s history. Having maintained its urban fabric and architecture – its residential and religious buildings, its markets, streets and squares – the city offers a vivid example of Islamic cities of the Middle Ages.[20]

World Heritage Status

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) named the Old City of Sana’a a world heritage site in 1986, and has described the area as such:

“The Old City of Sana’a is defined by an extraordinary density of rammed earth and burnt brick towers rising several stories above stone-built ground floors, strikingly decorated with geometric patterns of fired bricks and white gypsum. The ochre of the buildings blends into the bistre-colored earth of the nearby mountains. Within the city, minarets pierce the skyline and spacious green bustans (gardens) are scattered between the densely packed houses, mosques, bath buildings and caravanserais.”

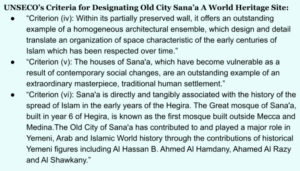

UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee has a set of 10 criteria it uses for classifying any archaeological or historically significant site as a World Heritage Site, with only one of these criteria necessary to meet the classification.[21] The Old City of Sana’a met three of these criteria (the fourth, fifth and sixth) in earning its designation.[22]

The Old City is distinguished by its buildings made of clay, burnt brick and stone.[23] Their roofs are covered with gypsum and qadad, a mixture of plaster, gneiss and lime that has been used in Yemen since the fifth century BC.[24] These buildings are four to nine stories high. They emerge from a network of markets, neighborhoods, tall minarets, narrow streets, groves, orchards and gardens. The Old City is estimated to cover an area of between 5.87 kilometers square.[25] Its roughly 56 residential neighborhoods contain 7,000 residential buildings, 42 mosques, 40 markets, and 15 hammams.[26] The population as of 2004, according to that year’s census, was 156,569.[27]

Difficulties Facing the Old City

Rainfall in August 2020 exposed the extent of the difficulties the Old City faces: of its 6,400 houses, according to UNESCO,[28] 1,000 were damaged severely, moderately or lightly.[29] This most recent acute damage compounds underlying issues in the service sector as a result of long-term degradation, ongoing conflict, and a lack of maintenance and repair.

A 2017-19 study by the GOPHCY, funded by UNESCO and the EU, assessed the condition of Old City infrastructure.[30] It found that important services – water, sanitation, roads, electricity and energy and telecommunications – were completely or partially defunct.[31]

The sewage network has exceeded twice its life expectancy and has not been updated at all since 1982.[32] The water network, which has almost 6,900 connections, equating to some 50,000 residents (with roughly seven people per household) is dilapidated and since 2011 has been effectively unable to provide water.[33]

A project began in 1984 to pave roads in the Old City, with the intent to thereby help preserve its buildings by redirecting rainwater away and preventing it from settling around the buildings’ foundations. However, ruptures and leaks in the water and sewage networks have caused extensive damage to the Old City’s roads. Some 66 percent of the Old City’s main and side streets have sustained moderate to substantial damage.[34]

According to Abu Bakr al-Jamra, a GOPHCY employee and vice president of the committee tasked with assessing buildings damaged by rain, catastrophic water leaks from the underground network are one of the greatest threats facing Old City buildings – greater even than the threat of heavy rainfall accumulation at ground level.[35] Since 2011, given that the main water pressure has remained weak, citizens have dug into the roads to connect their own pipes to the water network to supply their homes with drinking water; this results in leakages, affecting house foundations and road surfaces.[36]

Since the beginning of the war, the public electricity and energy providers have stopped servicing most areas of Yemen; the Old City of Sana’a is no exception. Many citizens have resorted to generators or solar power installations, resulting in a dense web of haphazard power lines that distort the city’s appearance and streetscape.[37]

Over the years, the telecommunications sector has also suffered damage due to neglect, obsolescence, lack of maintenance, and more recently the ongoing conflict and Saudi airstrikes in Sana’a. This has led to intermittent landline telecommunications network service in seven neighborhoods in the Old City.

The GOPHCY’s Role in Preserving Historic Cities

The General Organization for the Preservation of the Historic Cities of Yemen was established over a decade after the Old City of Sana’a was named a World Heritage Site. The 20th century had not been kind to the Old City, particularly after the September 26, 1962 revolution, when a post-revolution modernization effort took hold and the Old City walls were partially destroyed to make room for new houses.[38]

In 1979, there were calls to establish an independent governmental agency in charge of the Old City’s preservation. In the mid-1980s, two bodies were formed to handle this,[39] but their work was limited to determining the suitable ways to preserve historic cities.[40] The decision to establish the GOPHCY was made in 1997.[41]

According to Article 5 of Law No.16 of 2013, the GOPHCY is charged with preserving historic cities.[42] It has a broad mandate to take action to protect and preserve cities on the world heritage list or national heritage list. However, the law does not grant the organization the necessary power to prevent and punish violations, making its mandate impossible to fulfill. The issues that hamstring the GOPHCY are outlined below.

Legal Loopholes

The decision to establish the GOPHCY was issued in 1997, but the law the organization relies on to perform its work was not issued until 2013. During the 16 intervening years, plenty of violations occurred, many involving the use of improper building materials that threaten the character of the area, which the public prosecution for heritage preservation could neither curb nor punish.[43] The law itself, when it came, did not seriously deal with these violations; rather, it created a loophole allowing property owners to simply mask their alterations with traditional materials at the organization’s expense.[44] This practice – essentially the erosion of heritage – contravenes the recommendations of the World Heritage Committee and threatens the Old City’s status as a world heritage site.[45]

Although Article 126 of Law No.16 (2013) granted the organization’s employees the authority of law enforcement, it rendered this status toothless by limiting the organization’s work to simply identifying violations, rather than intervening to control or remediate them.[46]

Al-Jamra, the GOPHCY employee, outlined the organization’s work mechanism in responding to violations committed by citizens. When a violation occurs, the organization’s inspector tries to stop the person responsible and ameliorate the violation; however, in many cases, the person responsible does not respond to GOPHCY orders. The organization then files a report on the violation to the relevant security body. The organization’s work ends here; the issue is now in the hands of the relevant police department. Most of the time, these authorities do not prevent violations – often, according to al-Jamra, they just file a report on the violator’s failure to respond to orders.[47]

As a result, operations affecting built heritage continue in the Old City with no oversight or accountability. Between 2015 and 2018, the GOPHCY recorded 150 demolition operations and cement constructions, along with 15 instances of digging in search of treasure.[48]

Yemeni historic and cultural heritage, including the Old City of Sana’a, is also subject to additional regulations issued by, for instance, the ministries of tourism, public works and roads, water and environment, endowments and guidance, and local councils. Often, the priorities of these bodies conflict with those of the GOPHCY; they frequently obstruct the latter’s work, even issuing construction licenses without GOPHCY oversight.[49]

The Work Mechanism of the GOPHCY

In most of its work – whether conducting disaster response, maintenance, restoration or field surveys – the GOPHCY relies on domestic and international funding. When this support is not available, the organization’s work cannot continue. The GOPHCY’s weak response to the heavy rains in the Old City – its failure to save around 1,000 houses – has demonstrated its limited capacity.

The GOPHCY capital budget does not exceed YR260,000 monthly; it receives no more than YR2 million monthly from the Social Fund for Development (SDF), which covers the salaries of the organization’s 117 employees and 40 contractors.[50] Official wages have been largely suspended, however, since public sector wages in general were halted in mid-2016, and the organization’s income from building and restoration license fees and technical consultations is negligible. This extremely limited funding stream makes it impossible for the GOPHCY to carry out its work.

Currently, restoration works are being implemented in the Old City by the SDF, with the support of UNESCO and the EU. The project is part of a cash-for-work program that began in September 2018 and ends in August 2021, targeting historical buildings in four Yemeni cities.[51] The GOPHCY is relegated to a supervisory role: it has no contact with UNESCO and does not receive direct support from it. The SDF does not liaise with the GOPHCY on restoration work; instead, the former provides all the practical support for the project. But it is woefully inefficient. According to al-Jamra, the SDF releases project funding in fits and starts, delaying work for months. The GOPHCY can’t order the SDF to quickly finalize the project, but it shoulders the responsibility for the delay.

According to al-Jamra, this project was intended to restore 129 houses in the Old City, but so far only 80 have seen any work done. Some houses that were completely destroyed in the floods have yet to be worked on. The restoration work is prioritized according to the historic and aesthetic value of the buildings, without reference to humanitarian need. Nasser, a resident of the Old City, said: “My neighbor, whose economic situation has deteriorated, lost his daughter after the roof of their house collapsed. The GOPHCY included him in their inventory of damages and he’s now waiting for help – but has not yet received any.” Even those who do receive help might have restoration work halted partway through, on the basis of funding. As a result, many residents must either abandon their building or take on the repair costs themselves.[52] In Sana’a, numerous buildings remain completely or partially destroyed.

Coordination is lacking between governmental bodies in charge of restoration. These include the Ministry of Public Works and the Ministry of Endowments and Guidance, as well as the Amanat al-Asimah (Capital Municipality) district administration. This failure to coordinate can be dangerous. For instance, where building foundations have collapsed due to street washouts and repairing the latter is the job of the Amanat Al-Asimah public works office, restoration work has been limited to the building itself. Such an approach fails to protect against the wholesale collapse of the building.[53]

The GOPHCY’s work is extremely slow, because it tries as much as it can to restore houses faithfully, preserving any remnants. Once restoration work is finalized, the organization does not require the owners to return home or carry out maintenance work. This is counterproductive: restored houses that are abandoned may collapse due to neglect. Often, inhabitants are not incentivized to maintain the house because they are renters, or because the house is built on endowments, or Awqaf, property.

The latter situation pertains to 70 percent of Sana’a’s historic buildings – and most of the seriously damaged properties.[54] According to Article 26 of Law No.13, houses on Awqaf property fall under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Endowments and Guidance. As a result, the GOPHCY cannot carry out, intervene in or fund these works; its role is circumscribed to planning restoration projects and supervising their implementation.

Ultimately, the GOPHCY lacks the power and capacity to preserve the Old City of Sana’a and, indeed, all historic Yemeni cities. The organization relies on the support of governmental bodies and international organizations. Its strictly supervisory and preparatory role leaves it unable to shepherd through projects and liable to bear responsibility for their failure or delay. The law governing its work contains inherent contradictions: it stipulates that the GOPHCY is responsible for preserving historic cities but does not grant it the necessary powers – nor does it oblige other relevant bodies to carry out the work in their remit. A lack of awareness, conflicting priorities and weak coordination and cooperation between these bodies and the GOPHCY result in a chaotic implementation landscape that further limits the organization’s capacity, endangering the unique built heritage of Sana’a, and of Yemen more broadly.

This article was produced as part of the Yemen Peace Forum, a Sana’a Center initiative that seeks to empower the next generation of Yemeni youth and civil society activists to engage in critical national issues.

This article previously appeared in ‘Eye on the East – The Yemen Review, June 2021‘

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover diplomatic, political, social, economic and security-related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Endnotes

- “The Old City of Sana’a,” World Heritage Center, UNESCO, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/385/

- Iman Baydani, “Economic life in Sana’a in the third and fourth centuries hijri,” The History and Civilization of Sana’a, Vol. 2 (2005), 20.

- Mohammed Abdulaziz Saad Yusr, The Cultural Heritage of Old Sana’a (Sana’a: Sana’a University, 2013), 56-57.

- Mohammed Hussein al-Farah, “Sana’a’s old civilizational history,” Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2004, 39.

- “The Old City of Sana’a,” World Heritage Center, UNESCO.

- Abdullah Abdelsalam Saleh al-Hadad, Sana’a, its history and ancient homes [AR] (Dar al-Afaq al-Arabiya, 1999, Cairo), 24.

- Roland Lewcock, The Old Walled City of Sana’a (Belgium: United Nations Educational, 1987), 19-20. https://www.google.com/url?q=https://unesdoc.unesco.org/in/rest/annotationSVC/DownloadWatermarkedAttachment/attach_import_5318fc1e-5efa-43d4-b182-89080a8c6cb8?_%3D071940eng.pdf%26to%3D200%26from%3D1%23pdfjs.action%3Ddownload&sa=D&source=editors&ust=1621280874968000&usg=AOvVaw2Rdf7005-niLQFCB61VUl-

- Iman Muhammad Awad Bidhani, “Sana’a in the Writings of Muslim Geographers and Historians in the 4th century AH, from 300 AH – 400 AH”, House of Arab Culture for Publishing, Sharjah – United Arab Emirates, 2001, first edition, p. 208.

- Mohammed Abdo al-Sururi, “The History and Civilization of Sana’a,” Fifth International Conference on Yemeni Civilization, Vol. 2 (2005), 159.

- Yusr, Cultural Heritage of Old Sana’a, 113.

- This castle has been destroyed; some of its stones were used in the construction of the Great Mosque and houses in the Old City. Mohammed Abdulaziz Saad Yusr believes that Ghamdan Palace was west of the Salt Market. For more, see: Yusr, Cultural Heritage of Old Sana’a, 87-89.

- Ibid., 75-77.

- Youssef Mohammed Abdullah, Papers on the history of Yemen and its impacts [AR] (Beirut: Dar al-Fikr), 119.

- Iman Muhammad Awad Bidhani, “Sana’a in the Writings of Muslim Geographers and Historians in the 4th century AH, from 300 AH – 400 AH”, House of Arab Culture for Publishing, Sharjah – United Arab Emirates, 2001, first edition, p.89.

- Yusr, Cultural Heritage of Old Sana’a, 109-111.

- Ibid., 115-119.

- Abdullah, Papers on the history of Yemen, 120.

- Yusr, Cultural Heritage of Old Sana’a, 147-150.

- Ibid., 180.

- Ali Mohammed Amer, “Providing educational needs to the Old City of Sana’a according to the concept of sustainable conservation,” Journal of the Arab American University, Vol. 2, No. 2 (2016),

- General Authority for the Preservation of Historic Cities, http://www.gophcy.org/79/79/

- Old City of Sana’a, World Heritage Center, UNESCO, at the link https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/385

- Al-Hadad, Sana’a, 27.

- Mohammed Ahmad Abdelrahman Inab, “Preserving the cultural heritage of Yemen,” Arrafid, March 1, 2020, https://arrafid.ae/Article-Preview?I=QyNr2kNX6Gg%3D&m=5U3QQE93T%2F0%3D

- Yusr, Cultural Heritage of Old Sana’a, 50-51; Wael Abduljalil Moqbel Saad al-Bana’a, “The impacts of humanitarian aspects in preserving historical buildings in Yemen (Sana’a City as a case study),” master’s thesis, Faculty of Engineering, Asyut University, Egypt (2008), 144.

- Ibid., Wael Abdel-Jalil Moqbel Saad Al-Banna, “The Impact of Human Aspects on Preserving Historic Buildings in Yemen (Sana’a City as a case study)”, Master Thesis, Faculty of Engineering, Assiut University, Egypt, 2008 AD, p. 144.

- Yusr, Cultural Heritage of Old Sana’a, 50.

- “The Old City of Sana’a,” World Heritage Center, UNESCO.

- Statistics obtained by the author after the first survey of rainfall damage in August 2020.

- This study was part of a regional project by the EU that aims to protect cultural heritage and diversity in complicated emergency situations, in order to serve peace and stability. See: https://en.unesco.org/themes/culture-in-emergencies/Protecting-Cultural-Heritage-and-Diversity-in-Complex-Emergencies-for-Stability-and-Peace

- The General Organization for the Preservation of the Historic Cities of Yemen (GOPHCY), Study 2017-2019, http://www.gophcy.org/المشاريع-والانجازات/

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Abu Bakr al-Jamra, telephone interview by the author, October 14, 2020.

- GOPHCY Study 2017-2019.

- Ibid.

- Abdullah Abdullah Saad al-Fawri, “Legal framework for the restoration of historic cities in the Republic of Yemen,” master’s thesis, Institute of Arab Research and Studies, Egypt (2008), https://historicalcities.wordpress.com/الإطار-القانوني-لتنظيم-المدن-التاريخ/

- In 1984, a board of trustees was established to preserve the Old City of Sana’a. In 1985, the executive office to preserve the Old City of Sana’a was established in response to UNESCO’s first appeal on the matter.

- Al-Bana’a, “Impacts of humanitarian aspects in preserving historical buildings in Yemen,” 210.

- Al-Fawri, “Legal framework for the restoration of historic cities.”

- National Information Center, Law No. 16 of 2013, Article 5, https://yemen-nic.info/db/laws_ye/detail.php?ID=69331

- Abd al-Baset al-Noua’a, “The draft law on preserving historical cities .. has it been withdrawn from Parliament?”, Al-Thawra Official Newspaper April 18, 2018, http://althawrah.ye/archives/41562.

- National Information Center, Law No. 16 of 2013, Article 145.

- Rachid al-Hadad, “Draft law on preserving historic cities allows covering up buildings and is granting licenses allowing distortions, violating the recommendations of the world heritage council” [AR], Alsabaei News Agency, July 20, 2013, https://wwwalsabaeinet.blogspot.com/2013/07/blog-post_7784.html

- Ibid.

- Abu Bakr al-Jamra, telephone interview by the author, October 14, 2020.

- Mohammed al-Faiq and Belqis Mansour, “Sana’a, resisting fragrance and a history that never dies” [AR], Al-Thawra, Issue 19476, March 2018.

- Al-Fawri, “Legal framework for the restoration of historic cities.”

- Interview with Eng. Mujahid Tamish – Head of the General Authority for the Preservation of Historic Cities, Negotiable Program, Yemen Today Channel, February 19, 2021, (video: 15:52) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZRRGLnM2sAk

- The project aims to restore historical buildings in Aden, Sana’a, Shibam and Zabid. In Sana’a, the project intends to protect 129 buildings. See: “Cash for work: Promoting livelihood opportunities for urban youth in Yemen,” UNESCO, https://en.unesco.org/doha/cashforworkyemen

- Abu Bakr al-Jamra, telephone interview by the author, October 14, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية