The Sana’a Center Editorial

The Urgency to Protect Yemen’s Minorities

Through periods of tolerance and persecution, marginalization has remained a constant in the treatment of racial and religious minorities in Yemeni society. During the ongoing conflict, however, violence and subjugation against these marginalized groups has increased dramatically, to the point that it is fundamentally reshaping Yemeni society. For Yemen as we know it to continue to exist it needs to assure the existence of its minorities, as something fundamental to the makeup of a nation dies when its minorities perish.

Yemen’s Jewish community, with a history tracing back millennia, played a foundational role in developing Yemeni culture and commerce, and creating much of the artisanal industries for which the country is known. While the community had already been dwindling in recent decades, persecution at the hands of the armed Houthi movement following its takeover of Sana’a in 2014 has driven almost all the remaining Jewish families into exile, thereby extinguishing a part of Yemen’s soul. Similarly, as a recent Sana’a Center report details, Yemen’s Baha’i community is rapidly being driven out of existence by a systematic Houthi campaign of vilification and erasure.

The Muhammasheen – an ethnic underclass in Yemen literally referred to as Al-Akhdam, meaning ‘the servants’, by many in the country – have proved more useful to the various warring parties. As another Sana’a Center report details, both the Houthis and their rivals have actively sought out Muhammasheen communities at the margins of society to recruit their young men for the frontlines. At the same time, all sides in the conflict routinely deny wounded Muhammasheen access to healthcare and compensation and remove their families from the lists of beneficiaries for international humanitarian aid.

There is a reckoning with intolerance Yemeni society must undergo. No Yemeni – regardless of religion, race, sex, sexual orientation or other difference – should be denied legal rights and social protections. The incredible and liberating acceptance of difference that was alive amongst Yemenis of all backgrounds in the streets and squares during the 2011 revolution is a proof of concept that Yemeni society is capable of so much better.

The war, however, has brought urgency to the plight of marginalized groups in the country. While almost all Yemenis are suffering from this conflict, the struggle of marginalized groups has become an existential threat to these communities. Yemenis and regional and international stakeholders must take assertive steps to protect these vulnerable groups. For a just peace to emerge from any United Nations-led mediation efforts, the new UN special envoy must also seek to integrate protections for Yemen’s marginalized communities into the peace process.

Contents

-

Eye on the East

- Protests Simmer as Hadramawt Enter a Long, Hot Summer – By Shaima bin Othman

- Expat Returnees and Mukalla’s Entrepreneurial Resilience – By Nabhan Abdullah bin Nabhan

- Mukalla’s Arts & Culture Comeback After AQAP – By Shroq Al-Ramadi

- Dueling Mahri Scions Reveal Gulf Competition in Eastern Yemen – By Casey Coombs

- Socotra: A Paradise Divided – Photo essay by Quentin Müller

- Hudaydah, 30 Months on since the Stockholm Agreement: A Report from the Frontlines – By Salam al-Harbi

- The View from Iran after Raisi’s Election – By Adnan Tabatabai

- Redefining What Peace in Yemen Means and How to Achieve it – By Osamah al-Rawhani

- The Old City of Sana’a: A Living History Under Threat – By Wael al-Ahnomi

June at a Glance

The Political Arena

By Casey Coombs

Developments in Government-Controlled Territory

STC seizes control of state-run Saba News Agency

June 2: Forces loyal to the Southern Transitional Council (STC) stormed an office of the state-run Saba News Agency operated by the internationally recognized government in the interim capital, Aden. The vice chairman of the STC’s National Authority for Southern Media, Mukhtar al-Yafei, led the raid in Aden’s Al-Tuwahi district.

Al-Yafei claimed that he had directives from STC President Aiderous al-Zubaidi and Aden’s Governor Ahmed Lamlas to take control of the newsroom and rename it the Aden News Agency, a Saba employee told the Sana’a Center. Saba’s director, Mahmoud Thabet, contacted Lamlas, who denied knowledge of the raid and said he would communicate with Al-Zubaidi to resolve the situation, the employee said. As of June 9, Saba journalists reportedly remained locked out of the office, but continued to cover news remotely.

On June 7, STC forces raided a second Saba office in Aden, according to the Yemeni Journalists Syndicate. In recent months, several journalists and news outlets in Aden and surrounding governorates have been targeted based on their affiliation with internationally recognized government or the STC.

Government forces arrest STC media official in Shabwa

June 2: Political Security Organization (PSO) agents aligned with the internationally recognized government in Shabwa governorate arrested Thabet Abdullah Al-Khulaifi, the STC’s head of media operations in Shabwa’s capital, Ataq, for undisclosed reasons. Local media reported that he was released from the PSO prison there on June 17, which was also independently confirmed by the Sana’a Center. Al-Khulaifi was arrested in mid-February by the same intelligence agency and held for three months for reasons which have still not been disclosed.

Aden governor launches ban on guns, unmarked vehicles in the interim capital

June 22: Aden authorities extended enforcement of a ban on unlicensed arms, unregistered vehicles and the unauthorized sale of military attire, part of efforts to consolidate the authority of Aden’s security and military forces. Governor Ahmed Lamlas, who met with security officials to evaluate the first week of the campaign, said unlicensed light weapons and ammunition had been seized, without indicating the quantity. Awareness efforts preceded enforcement, and traffic police chief, Col. Jamal Diane, said that more than 1,420 cars had been properly registered in the week since the campaign began.

‘Socotra Dream’ ferry service unveiled

June 8: Prominent Mahri businessman and politician Abdullah Issa bin al-Afrar unveiled a newly acquired ship called Socotra Dream, which will shuttle passengers to and from the island of Socotra from Al-Mahra governorate. In a series of tweets, Al-Afrar provided details about the ship and praised the late Omani leader Sultan Qaboos bin Said for bankrolling the purchase of the boat. Al-Afrar has aligned with competing Gulf powers vying for influence in Al-Mahra and Socotra throughout Yemen’s civil war. After falling out with the Saudi-led coalition in 2017, he moved to Muscat and supported an Oman-backed peaceful protest movement in Al-Mahra that seeks to expel the Saudi military from the governorate. Since June 2020, when the UAE-backed STC forces seized Socotra’s capital from the internationally recognized government, Al-Afrar has gravitated back into the Saudi-led coalition’s orbit, having endorsed the STC’s armed takeover (see also, Dueling Mahri Scions Reveal Gulf Competition in Eastern Yemen).

STC forces detain activist on Socotra

June 8: STC-affiliated forces detained Yemeni activist Abdullah Bidahen for four days in Socotra for criticizing Emirati influence over the group on Facebook. It is the second time Bidahen has been detained by STC forces since the separatists seized control of the archipelago from the internationally recognized government in June 2020.

National Resistance Forces on Mayun Island, says Tareq Saleh

June 15: The commander of the National Resistance Forces, Brigadier General Tareq Saleh, has claimed his Emirati-backed troops are stationed on Mayun island near the Bab al-Mandab Strait, where an air base is under construction. The comments by Saleh, who is the nephew of the late President Ali Abdullah Saleh, follow an Associated Press story in May that highlighted the base’s construction. Ship-tracking data showed that at least two Emirati-owned vessels had traveled to Mayun in the first two weeks of June.

Gov’t special forces arrest STC’s Hadramawt delegation in Shabwa

June 18: Special forces affiliated with Yemen’s internationally recognized government in Shabwa governorate’s southern Radum district detained the head of the STC’s Hadramawt branch, Dr. Muhammad Jaafar bin Al-Sheikh Abu Bakr, as well as his deputy for coordination of university affairs, Dr. Hassan Saleh Al-Ghulam Al-Amoudi, and a number of other STC officials as they were returning to Hadramawt from Aden. The STC officials were taken to a special forces’ prison in Radum district, sources in the 2nd Marine Infantry Brigade in the district told the Sana’a Center.

STC security forces clash in Aden

June 23: Rival STC forces clashed with each other in Aden’s Sheikh Othman district, highlighting internal tension in the UAE-backed secessionist group that controls the interim capital. Forces under Salafist Security Belt Commander Mohsen al-Wali and the commander of the Third Support and Backup Brigades, Nabil al-Mashushi, fought those under Captain Karam al-Mashraqi, who leads a unit of the Security Belt forces in Sheikh Othman. The Security Belt forces and the Support and Backup Brigades are the most prominent security forces in Aden and present themselves as one institution on their shared website. Video footage showed smoke rising from the Ministry of Education building as a result of the street fighting. After the battle, Al-Mashraqi, who is from Sheikh Othman and whose forces are based there, said in a video circulated on social media that Al-Mashushi would not be allowed to enter the district. Al-Wali and Al-Mashushi are from the Yafei region in Lahj governorate, from where a number of senior STC officials hail. Two days after the clashes, on June 25, STC President Aidarous al-Zubaidi appointed Al-Wali top commander of the Security Belt forces.

Government forces detain STC officials in Shabwa

June 23: Soldiers at a checkpoint in Shabwa detained a member of the STC National Assembly, Ahmed al-Awlaqi, Salah Abu al-Khalaf, and others on their way to attend demonstrations in the Abadan area west of the capital Ataq to condemn kidnappings and other heavy-handed treatment by the internationally recognized government in Shabwa. They were released the next day.

STC pulls out of Riyadh Agreement talks

June 26: STC spokesman Ali Abdullah Al-Kathiri announced the suspension of communication with the internationally recognized government on negotiations to implement the Saudi-sponsored Riyadh Agreement. Al-Kathiri cited the “Muslim Brotherhood militias’” recent crackdown on the STC in the Abadan areas of Nisab district, which he said was “organized by the people of Shabwa governorate to express their aspirations and their rejection of the aggressive and oppressive approach that these militias practice, such as blocking roads and looting locals, raiding villages and homes, and continuous kidnappings against the people of Shabwa and the south in general.” The internationally recognized government in Shabwa has tried to prevent large-scale demonstrations in the governorate, fearing that they could spur a power grab by the STC, which tried and failed to seize control of Ataq in August 2019.

Hadi travels to US for medical checkup

June 26: President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi began a trip to the United States for a medical check up. He has made several medical visits to the Cleveland Clinic over the past six years.

Developments in Houthi-Controlled Territory

Houthi leaders say UN Talks over Red Sea oil tanker halted

June 1: After 10 days of intensive talks in which the UN tried to negotiate access to the FSO Safer oil tanker, the Houthis released a statement saying that the discussions had reached a deadlock. Stephane Dujarric, spokesman for UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, said the statement from the group “would seem to confirm that Ansar Allah is not ready to provide the assurances the UN needs to deploy a UN mission to the Safer tanker.”

After his briefing the Security Council, UN special envoy Martin Griffiths told reporters that the Houthis want the UN mission “to actually repair the tanker and not just assess and do the small repairs that are maybe needed to stabilize it.”

Human Rights Watch details Houthi campaign to stifle COVID-19 information

June 1: Health workers told Human Rights Watch that the Houthis had embedded a special intelligence unit under the command of its political security arm in medical facilities to intimidate health care staff and limit the information they can disseminate regarding the COVID-19 outbreak. Houthi authorities have tried to limit information on the effects of coronavirus in Houthi-controlled areas throughout the pandemic.

Houthis ban singing at weddings, regulate marriage dowries

June 22: A memo from the Houthi governor of Sana’a, Abdul Basit Al-Hadi, banned singing at weddings in the capital in order to “curtail the phenomenon of artists and artists performing at events and weddings by promoting Quranic awareness within the community.” Days earlier, several documents surfaced on social media showing Houthi directives obliging tribal sheikhs to help limit the cost of marriage dowries in an effort to make it easier for people to marry, with bride prices in Sana’a not to exceed 600,000 Yemeni rials (though price limits varied by governorate). In January, the Houthi-run Ministry of Health and Population banned the use of birth control as part of broader efforts to raise the birth rate.

Following abuse in Houthi prison model attempts suicide, lawyer suspended

June 28: Imprisoned Yemeni actress and model Entisar al-Hammadi attempted to hang herself after being referred to the “prostitution section” of the Central Prison in Sana’a, according to her lawyer Khaled al-Kamal. A Human Rights Watch investigation summed up Al-Hammadi’s mistreatment in Houthi custody: She was arrested on February 20 by Houthi forces and held at the Criminal Investigation Department in Sana’a for 10 days before anyone was notified of her whereabouts. She was transferred to the Central Prison in Sana’a in March, where guards verbally abused her, calling her a “whore” because of her profession and “slave” due to her dark skin and Ethiopian origin.

Plans for a forced “virginity test” were halted after Amnesty International published a report on the development. Houthi authorities suspended her lawyer, Al-Kamal, prior to her first court hearings on June 6 and on June 9, in an attempt to undermine the trial. Al-Kamal had previously received threats to walk away from the case. In late April, Houthi authorities replaced a prosecutor who ordered al-Hammadi’s release after concluding she was not guilty of a crime.

Specialized criminal court orders crucifixion of convicted AQAP leader

June 29: The Houthi-run court in Sana’a sentenced Majdi al-Mutawakel, the Sana’a emir of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), after convicting him of assassinating the Houthi representative to the National Dialogue Conference (NDC), Ahmed Sharaf El-Din, in January 2014, and killing five other men between 2011 and 2015. The sentence stipulates death by firing squad in Al-Sabaeen square in Sana’a, after which his body is to be displayed for two days on a cross in the square.

International Developments

Omani delegation travels to Sana’a to facilitate peace talks

June 5: An Omani delegation arrived in Sana’a for a week of talks with Houthi leaders to push for peace. The visit coincided with a visit to Muscat by the internationally recognized government’s Foreign Minister Ahmed bin Mubarak. On June 11, the Omani delegation departed Sana’a, accompanied by the head of the Houthi negotiating delegation, Mohammed Abdel Salem, with no announcements of progress from the talks.

Hamas honors Houthi leader in Sana’a

June 7: Moaz Abu Shamala, a representative of the militant Palestinian organization Hamas, gave senior Houthi leader Mohammad Ali al-Houthi a gift of appreciation for launching a fundraising campaign to support the group amid Israel’s recent military campaign in Gaza.

US seizes domains of Houthi-run news outlet Al-Masirah

June 22: The US Justice Department seized the domains of 33 websites associated with a sanctioned Iranian broadcaster affiliated with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force, including the Houthi-run site Al-Masirah. The 33 domains, which are owned by a US company, were illegally obtained and not registered with the US Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control. While the websites using the US domains are no longer active, many of the sites, including Al-Masirah, continue to operate under other domains.

Casey Coombs is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies and an independent journalist focused on Yemen. He tweets @Macoombs

State of the War

By Abubakr al-Shamahi

Marib: Fighting ramps up but frontlines unchanged

The stalemate in Marib continued in June, with the Houthis unable to make any significant progress on the governorate’s frontlines, and Yemeni government forces unable to push the group back away from their positions near Marib city. The first half of the month saw relatively low-level fighting in areas to the west and northwest of Marib city, in Al-Kassarah, Al-Zour, Al-Mashjah, and Al-Tala’ah Al-Hamraa. Yemeni government forces continued to hold their ground on the frontlines in those areas, much as they have since April, with Saudi-led coalition airstrikes helping to deter Houthi advances.

Instead, Houthi forces have fired frequent missiles at Marib city, hitting both military and civilian areas. Particularly deadly attacks included a June 5 missile attack on a fuel supply station run by the Yemeni government’s 3rd Military Region forces in Marib city’s Al-Rawdhah area, which killed 21 people, including two children, according to locals and media reports. On June 10, Houthi forces attacked a compound in Marib city housing government buildings with missiles and drones, killing four civilians and 10 security personnel, according to victims’ relatives and media reports.

The second half of June saw some of the most intense fighting on the frontlines in Marib since mid-May. However, the focus of the fighting was not on the previously mentioned frontlines directly to the west and northwest of Marib city, but rather in Raghwan district, further to the north, where control is divided between the two sides. On June 19, the Houthis launched two attacks on Yemeni government positions, in western and northwestern Raghwan respectively. While the Houthis were initially able to make some advances, Yemeni government and allied tribal forces, backed by Saudi-led coalition airstrikes, were quickly able to push them back on the same day. Fighting continued in Raghwan throughout the rest of the month, with pro-Yemeni government sources telling the Sana’a Center that dozens had been killed on both sides.

The Houthi push in Raghwan appears to be an attempt to launch a new starting point for attacks toward Marib city, in light of the stalemate on the other frontlines near the city. However, the Yemeni government forces’ tactics in Raghwan may be an attempt to drain the Houthi forces by soaking up their attacks; the Yemeni government has reinforced its forces in the district, fortified its positions, and can also rely on the support of coalition airstrikes.

In another effort to strengthen their position in Marib, Houthi forces have also made a renewed effort to take the Yemeni government’s Al-Khanjar base, in southwestern Jawf governorate, to the north of Marib governorate. On June 3, Houthi forces captured the northern gate of the base, before being forced to retreat in the face of a counterattack from the Yemeni government’s 6th Military Region forces, backed by coalition airstrikes, Houthi and government military sources told the Sana’a Center. Fighting continued around Al-Khanjar for the rest of June, with both sides sending new commanders and reinforcements to the area, reflecting the importance of the base to controlling the Jawf-Marib road.

Taiz: Continued clashes within the anti-Houthi coalition

Fighting between Yemeni government and Houthi forces continued in Taiz governorate, concentrated in Maqbanah and Hayfan districts. However, no advances were reported on either side, and a government offensive that began in March has effectively ended. Instead, infighting within the government ranks emerged once again, as a result of long-running tension between the Islah-dominated Taiz Military Axis and rival political forces within the broader anti-Houthi camp. The Islah-affiliated 5th Support Brigade clashed with Central Security Forces units on several occasions in mid-June near Al-Turbah, a city in southwestern Taiz’s Al-Shamayatayn district. The fighting resulted in the Central Security Forces units withdrawing from their positions in Jabal Munif and Jabal Bayhan, as pro-Islah forces continue their expansion in Taiz governorate, most notably in Al-Hujariah area, which includes Al-Turbah.

At the same time, tensions increased in mid-June in Hayfan district, after the 4th Hazm Brigade refused to allow the leadership of the Islah-affiliated 4th Military Region forces to pass through Wadi Al-Dhabab. The 4th Hazm Brigade is largely made up of members of the Al-Sabiha tribes, which are affiliated with the Southern Transitional Council (STC). Local mediation efforts throughout the second half of June were able to prevent clashes, but on June 28 and 29 the Taiz Military Axis moved the 4th Mountain Brigade to the borders of Tur Al-Bahah district in Lahj, a decision that has angered the STC. The Houthis, meanwhile, may seek to use the divisions within the anti-Houthi camp to their advantage, and seize the initiative in Taiz.

Al-Dhalea, Lahj, Aden, and Shabwa: Gov’t and STC rivalry intensifying

Divisions within the anti-Houthi camp have been prominent in Yemen’s southern governorates, despite fighting against the Houthis continuing in June in Al-Dhalea and Lahj governorates. Both the Yemeni government and the STC have intensified their media campaigns against each other, and this has been coupled with the takeover of government-run media buildings in Aden by gunmen affiliated with the STC, and arrests of STC-affiliated civilians, politicians, and fighters by Yemeni government forces in Shabwa. On June 25, clashes occurred between the Yemeni government’s Joint Security forces and the STC-affiliated Southern Resistance forces in Abadan area, western Shabwa governorate, after government forces prevented STC supporters from travelling to a pro-STC event in Ataq that was scheduled for the next day.

AQAP kidnaps officers in Shabwa, bombs market in Abyan

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) activity was also reported in Shabwa in June. The group kidnapped five officers from the Ataq-based Criminal Investigation Department in Wadi Khawrah, southwestern Shabwah, on June 14. AQAP released a video of the five officers on June 25, and is demanding the release of more than 10 AQAP members held in coalition prisons. Meanwhile, in Abyan, a June 11 bomb attack near Zinjibar city’s qat market was blamed by security officials on AQAP. Two civilians and six soldiers were killed in the attack.

Abubakr Al-Shamahi is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies.

Economic Developments

By the Sana’a Center Economic Unit

US Department of Treasury lists one of Yemen’s biggest money exchangers

On June 10, the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) added one of Yemen’s biggest money exchangers to its list of specially designated nationals list (SDN). Swaid & Sons For Exchange Co. was listed in connection with ‘Turkey-based Syrian national Talib ‘Ali Husayn al-Ahmad al-Rawi and Greece-based Syrian national Abdul Jalil Mallah,’ who were also listed by OFAC. Swaid & Sons For Exchange was identified as a key facilitator for the transfer of millions of dollars to Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force officials deployed in Yemen. The US Department of Treasury stated that ‘al-Rawi has worked with Sa’id al-Jamal to transfer millions of dollars from Qatirji Group purchases of Iranian petroleum products to Swaid and Sons in Yemen.’

On June 15, Swaid & Sons For Exchange issued a statement in which it expressed its readiness to challenge the OFAC listing and denied the allegations made against the company. The Sana’a-based Yemeni Exchangers Association (YEA) issued its own statement on June 17 in defense of Swaid & Sons For Exchange Company. The YEA reiterated its repeated calls for the depoliticization of financial and banking activities in Yemen.

On June 17, the Aden-based public prosecution office issued a decree related to the parties designated by the US Treasury Department, placing them on a terrorism blacklist, ordering that any operating licenses be revoked and banning any commercial and financial transactions with them. Four days later, the Yemeni government-controlled central bank in Aden issued a circular demanding Yemeni commercial banks and money exchange outlets implement the public prosecution office’s decree.

CBY–Sana’a aims to restrict circulation of rial banknotes issued by CBY-Aden

The Central Bank in Sana’a issued several circulars during the last week of June that aimed to regulate the circulation and use of ‘new’ 1,000 Yemeni rial (YR) banknotes issued by the Central Bank in Aden. The Houthis accused the internationally recognized Yemeni government of feeding newly-printed YR1,000 banknotes into Houthi areas that bear a very close resemblance with existing ‘old’ Yemeni rial banknotes (i.e. those issued before 2016). In a circular that the Central Bank in Sana’a issued on June 22, it claimed that the new YR1,000 banknotes arrived as part of a shipment of YR400 billion to Mukalla port, adding that the government then circulated YR60 billion of these new banknotes in Aden and Mukalla on June 21.

The same June 22 circular that the Central Bank in Sana’a issued contained specific details on how to distinguish between the permitted ‘old’ YR1,000 banknotes, with reference to the serial numbers used on both the ‘old’ and ‘new’ bills. Only YR1,000 banknotes with a serial number starting with the letter (ا) will be accepted, all others, such as those starting with the letter (د) are not permitted. Businesses operating in Houthi-controlled areas, as well as the general public, appear to have widely abided by the decree. Those caught violating the decree have had their new YR1,000 banknotes – which the CBY-Sanaa have deemed “forged” – confiscated by Houthi authorities.

The Central Bank in Sana’a later issued a separate circular stating that people travelling from non-Houthi areas to Houthi areas were restricted to carrying no more the 100 ‘old’ YR1,000 bills with them.

Houthi-run YPC announces introduction of new ‘official’ fuel prices

On June 11 the Houthi-run Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) announced the introduction of new ‘official’ prices in Houthi-controlled territories for fuel sold at YPC stations or privately owned stations that are agents of the YPC. The price of petrol was set at YR8,500 per 20 liters while the price of diesel was set at YR7,900 per 20 liters.

The official announcement sees ‘official’ fuel prices fall from YR11,000 per 20 liters for both petrol and diesel that was introduced at the end of April and continued to be implemented throughout May. Although the ‘official’ price is now lower than in previous months, the amount of fuel that is available at the official price is limited. There are continued consumer restrictions in place, with consumers only permitted to fill up their vehicles with 30 liters of petrol or diesel once every six days. There are a small number of fuel stations selling fuel at the official price during different time-slots spread out over a twelve-hour period during the day. There are long queues at these fuel stations, leading consumers to purchase fuel at the inflated, parallel market price of YR12,500 per 20 liters as sold at privately-owned fuel stations in Houthi areas.

Since the beginning of the year, there has been reduced import activity at Hudaydah Port and increased import activity at other sea ports, specifically Aden and Mukalla. Fuel is then being transported overland to Houthi-controlled territories. Although there is a correlation between reduced import activity at Hudaydah Port and increased fuel prices in Houthi-controlled territories, correlation does not equate to causation. In reality, the Houthis almost certainly increased the official price of fuel and ensured more fuel is sold at the parallel market price in order to try and recoup the fuel revenues they would be in position to generate when fuel enters directly via Hudaydah Port uninhibited.

Houthis Demand Access to Funds Held by Tadhamon Bank

On June 27, the head of the Houthi Specialized Criminal Court, Abdullah Mohammed Zahra, issued a circular demanding that Tadhamon Bank transfer billions of Yemeni rials and Saudi riyals held in three separate accounts believed to belong to Yemeni President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi. The Specialized Criminal Court ordered Tadhamon Bank to transfer the money to an account at the Central Bank in Sana’a (account number: 00-2000145).

|

Client’s name |

Amount |

Currency |

Account No. |

|

Abdrabbu Mansour Hadi |

31,289,623.900 |

Yemeni Riyal |

001-886-271107-000 |

|

636,221,984.25 |

Saudi Riyal |

112-682-211101-000 |

|

|

907,722,643.44 |

Yemeni Riyal |

112-886-211101-000 |

Zahra referenced previous rulings from the Specialized Criminal Court (No. 102 of 2019, and case No. 407 of 2019) in which the court sentenced Hadi to execution in absentia and declared its intention to confiscate Hadi’s fixed and movable assets. The Financial Information Unit (FIA) of the Central Bank in Sana’a issued its own letter on June 28 referenced the order from the Specialized Criminal Court and called on all financial institutions to freeze any Tadhamon Bank deposits and funds.

Tadhamon Bank responded with a detailed letter to the Governor of the Central Bank in Sana’a, Hashem Ismail Ali Ahmad, on June 28. In the letter Tadhamon Bank explicitly opposed the demands made by the Specialized Criminal Court. Tadhamon Bank stated that if it were to transfer the funds held in the accounts listed by the Specialized Criminal Court then it could face action from the UN Sanctions Committee that monitors compliance with UN Security Council sanctions. Tadhamon Bank also highlighted warnings that Yemeni banks had received from the UN Sanctions Committee regarding the acceptance of decisions made by the Houthi-run Specialized Criminal Court and the Judicial Guards, headed by Saleh Misfar Saleh al-Shaer. Compliance with demands made from either institution could be deemed as a direct contravention of anti-money laundering and combatting the financing of terrorism principles. Tadhamon stressed how any subsequent action taken by the Sanctions Committee against Tadhamon (or any other bank) would exacerbate the existing difficulties that the formal banking sector in Yemen faces, such as reduced access to correspondent banks.

On the same day as Tadhamon Bank issued its response, the head of the Houthi-run Financial Information Unit of the CBY-Sana’a, Wadih Muhammad al-Sada, issued a circular to money exchange companies located in their areas of control to “immediately seize all funds of Tadhamon International Islamic Bank deposited with you and provide us with all the seized funds and balances today.”

In the latest UN Panel of Experts on Yemen report, the Panel identified Al-Shaer as ‘a key figure in the Houthis’ efforts to confiscate assets from opponents and businessmen, and a very close ally to Abdulmalik al-Houthi, a listed individual.’ The Panel described him as ‘the judicial custodian of funds and assets appropriated from Houthi opponents’ and noted how the Specialized Criminal Court essentially gave Al-Shaer and the Judicial Guards the legal cover to confiscate the funds and assets of the Houthis political opponents.

Tadhamon Bank noted that funds held in the Yemeni rial account were invested in Islamic bonds at the Central Bank in Sana’a, while the Saudi riyal account concerned a foreign investment account the client owned that was covered by agreements that date back to 2014.

Features

Eye on the East

The governorates of Hadramawt and Al-Mahra in Yemen’s east, and the island of Socotra offshore, have been spared the frontline fighting that has ravaged much of the country during the ongoing conflict. This distance from the battles, however, has also placed these areas outside of the spotlight, even while evolving regional geopolitical factors and local economic and cultural dynamics are bringing about societal changes at a rapid pace.

This month, The Yemen Review focuses on the country’s east. Shaima bin Othman writes about the summer of protests in Hadramawt, discussing how one of Yemen’s most prosperous governorates has effectively split in two, with a coastal Hadramawt controlled by the governor and head of the 2nd Military Region, Faraj al-Bahsani, and Wadi Hadramawt, which is largely under the control of the 1st Military Region in Sayoun. Also in Mukalla, Nabhan Abdullah bin Nabhan discusses how, despite the huge economic challenges the country is facing, a determined segment of expatriate Yemeni entrepreneurs returning from Saudi Arabia have been starting successful new businesses in the city. Meanwhile, Shroq al-Ramadi writes about how a vibrant arts and culture scene has been making a comeback five years after Al-Qaeda’s occupation of Mukalla.

Farther east, Casey Coombs writes about the internal divisions within Al-Mahra’s dynastic Al-Afrar family, in which Abdullah al-Afrar has been trying to balance alliances between Gulf patrons of Saudi Arabia and Oman, both of which are competing for supremacy in the governorate. In Socotra, home to another branch of the Al-Afrar family, Quentin Müller captures the natural beauty and recent social and political changes on the island in a photo essay.

Protests Simmer as Hadramawt Enter a Long, Hot Summer

By Shaima bin Othman

For much of the past three years, periodic protests have rocked Mukalla, a port city and the capital of Yemen’s Hadramawt government. The cause, typically, is Mukalla’s poor electrical grid and frequent outages, although at times politics and Yemen’s broader war have bled into the protests. In turn, the authorities have continued to intensify their response this year in attempting to quash the unrest. In March 2021, for instance, it was university students who took to the streets, frustrated with the declining value of the Yemeni rial (YR) and rising fuel costs. Days after that, security and military forces cracked down hard on yet another protest, firing live and rubber bullets at the demonstrators, killing one and injuring several others.

Faraj al-Bahsani, the governor of Hadramawt, declared a “state of emergency” and said he was forming a committee to investigate the incident. Ibrahim Haidan, the Minster of the Interior, also formed a special committee to investigate. Neither committee has yet to release its results.

While Bahsani’s emergency declaration effectively banned public demonstrations it has done little to change the public’s mood. Electricity coverage is still poor and the rial recently reached an all-time low in southern Yemen, trading at YR1,000 against the US dollar.

A Multitude of Protests

The student protest in March was organized by the Hadramout University Students’ Union, and leaders demanded the government reverse its decision to raise fuel prices, prevent the devaluation of the currency, control the cost of food and housing while also reducing school fees to account for the rial’s loss in value. Many protestors have blamed Al-Bahsani, the governor, who is also head of the 2nd Military Region and commander of the Hadrami Elite Forces, which are backed by the UAE. Al-Bahsani has dismissed many of these as “paid saboteurs.” There have also been frequent demonstrations against reduced purchasing power, violations of human rights, as well as calls to release political prisoners.

Even women have taken to the streets. In March 2021, women marched with their children, calling for an end to corruption and asking officials to deal with the currency collapse and rising prices.

Their demonstration, as well as that of the students, came at a time of rapidly rising fuel prices in Hadramawt. Between January and March 2021, fuel prices rose 30 percent. For the student protesters, this means that many could no longer afford to travel to university for classes.

Tariq Banni, a student at Hadramout University said, “Dozens of students from my city will have to stop studying if the (situation) continues in this manner. Parents who receive a monthly salary of YR70,000 cannot provide a YR25,000 transportation fee per child. Not to mention the tuition fees and the student’s needs of books, stationery, and other items.”

Governor Al-Bahsani formed a committee in early March to look into the students’ demands and produce recommendations. But with no solution in sight, the governor suspended university operations under the justification of a new wave of COVID-19.

In June, universities reopened, but fuel prices remained high. In coastal Hadramawt, local authorities took no steps to remedy the situation. However, in Wadi Hadramawt, Esam al-Kathiri, vice-governor for Wadi Hadramawt and Desert affairs, formed a committee that recommended supporting all student transport costs to offset the fuel price increases. Unlike coastal Hadramawt, Wadi Hadramawt is relatively less socially unstable, with better service provision and electricity. Since 2018, there has only been one significant public demonstration, with protesters denouncing the security situation, especially the increasing cases of assassinations.

Extrajudicial Detention

Along with the protests, concerns about rights and freedoms are intensifying due to the manner in which Al-Bahsani is dealing with citizens. On May 27, 2020, authorities arrested several individuals working at the Governor’s Office, including Abdullah Bukair, a media specialist, Ahmed Alyazidy, an IT specialist, and Fahmi Baafia, a cook. On June 3, the Specialized Criminal Prosecution (SCP) issued a press release justifying the detentions, claiming that the arrests foiled an assassination plot targeting Governor Al-Bahsani. However, no arrest warrants were ever issued.

After four months of detention, and amidst an ongoing campaign by journalists, human rights organizations, and activists, the Specialized Criminal Prosecution in Mukalla agreed to start prosecution procedures. In April 2021, nearly one year after the arrests – following a drawn out trial in which no solid evidence was ever produced, protests, and a hunger strike by the detainees, which led to their deteriorating health, according to Reporters Without Borders – Bukair and the others were released.

Media Crackdown

According to the Media Freedoms Observatory in Yemen, Hadramawt recorded 49 cases of violations against members of the press from 2015 until September 2020, including kidnappings, arrests, threats, and torture. Local activists claim that authorities established a “monitoring room” to track journalists’ and activists’ posts on social media.

Muhammad al-Yazidi, a local journalist, said on Facebook that in September 2020 he was threatened, pursued, and the victim of an attempted kidnapping by armed men in civilian clothes, who he later said were affiliated with Military Intelligence in Hadramawt. The security authorities in Hadramawt arrested his brother two months later, in November, which Muhammad said was an attempt to intimidate him and stop him from reporting on corruption cases and the collapse of public services in Hadramawt. The authorities are currently pursuing Yazidi through the courts and he has fled Mukalla.

At the same time, Mu’taz al-Naqib, a reporter for Yemen Shabab TV, was assaulted and his equipment confiscated by soldiers from the 2nd Military Region. Also, Al-Mahariya TV correspondent Zakaria Muhammad was arrested after covering a protest in front of the gate of the governorate building.

As Hadramawt’s infrastructure continues to languish it is likely that the protests will also continue, particularly as the summer heats up and the difference between the availability of electricity in Wadi Hadramawt and Coastal Hadramawt becomes more pronounced.

Shaima Bin Othman is a policy analyst, activist, and social researcher. She is a fellow with the Sana’a Center’s Yemen Peace Forum and with the Yemen Policy Center. She has previously published in al-Madaniya magazine and is currently an MA candidate in Middle East studies at the American University in Beirut.

Expat Returnees and Mukalla’s Entrepreneurial Resilience

By Nabhan Abdullah bin Nabhan

When Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) took control over Mukalla in 2015, a young man opened a shop to sell fast food in our neighborhood. The shop was popular; the food it served was the first of its kind in the city. The diverse menu, impressive packaging and employees’ professionalism reflected good management during a period when job opportunities were scarce, consumers were focused mostly on only buying essentials and many of the city’s established merchants were fleeing eastward toward the security of neighboring Oman.[1] Investing in a new venture at a time of such uncertainty might seem strange, but the enterprising restaurant owner had little choice. He was one of hundreds of thousands of Yemeni expatriate workers compelled to abandon their lives in Saudi Arabia due to an intensifying campaign in the kingdom to reduce its reliance on foreign workers.

Remittances from Saudi Arabia to Yemen total billions of dollars annually and are currently the country’s largest source of foreign currency.[2] As expat workers return home and these transfers fall, so too do the incomes of hundreds of thousands of Yemeni households that depend on them. Less foreign currency in Yemen also puts pressure on the Yemeni rial, driving up prices for many basic commodities and other goods.[3] These economic impacts are undeniably devastating on a broad scale. A less discussed consequence of the repatriation of Yemeni workers, however, is that they include a segment of skilled entrepreneurs who are being reintegrated into the Yemeni market, many of whom are keen to build their businesses despite the challenges of operating in Yemen’s conflict-torn economy.

While no statistics regarding the precise number of expatriate returnees is available, it is clear that they are a budding segment of Mukalla’s small- and medium-sized business sector. This article looks at the specific cases of two enterprising young women who overcame multiple barriers to build businesses in niche market segments, and uses their examples to highlight the types of opportunities and challenges facing new entrepreneurs in the city.

Background of the Business Environment

Mukalla is the capital city of Hadramawt governorate. Prior to the war, commercial activity in Mukalla was stable relative to most urban centers in Yemen, with the largest employment sector being the construction industry – fueled by investments from a wealthy Hadrami diaspora – followed by the public service, commercial activities, industry, transportation, fishing, and tourism.[4] The city’s main streets and public squares – such as Khour al-Mukalla, Cornish al-Mukalla, Cornish al-Mahader and Al-Aroud Square – had profited from tangible development and expansion in 2005, work done as part of commemorations marking 15 years since Yemen’s unification. Notably, however, there were no projects to expand electricity, sanitation or water services at that time. Nearby Al-Rayyan Airport was then operating domestic and international flights and the city’s main port handled more than 1 million tons of cargo in 2014.[5] Yemen’s macroeconomic woes over the years have presented challenges for businesses across the country. Yet in Mukalla, a small city of just under 350,000 people in 2014, the factories, hotels, hospitals and various companies that make up the commercial sector did not face severe local challenges.[6] [7] This population has since risen to an estimated 536,000, due in part to returning expatriate workers but more so because of the influx of people displaced by the war.[8] Even during AQAP’s presence in the city, Mukalla received an estimated 150,000 displaced people from Aden and other governorates.[9]

Since the escalation in the war in 2015, rising inflation and a falling currency value have eroded incomes and savings across the country. Mukalla has been no exception.[10] Although AQAP made some initial investments in the city’s infrastructure to try and curry favor with residents,[11] the extremist group’s rule quickly became oppressive and drove many of Mukalla’s merchants to look for opportunities elsewhere. Many chose to make a new base in the Omani city of Salalah or in the free zone area of Al-Mazyunah between Oman and Yemen.[12] The central bank branch in Mukalla was shuttered and looted, and commercial banks were closed for a number of weeks. When they resumed, activity was minimal.[13]

On April 24, 2016, AQAP was ousted from Mukalla by United Arab Emirates-backed local forces. The internationally recognized Yemeni government took back control of the city under the leadership of Governor Ahmad Bin Breik, who took a series of measures to help restore commercial activity.[14] For instance, prior to AQAP’s control of Mukalla, entrepreneurs in the city had been required to undergo a time-consuming process of obtaining their licenses centrally from the Ministry of Trade and Industry. To facilitate investment, Bin Breik authorized the ministry’s local offices to handle this task, streamlining the process and making it easier for new businesses to be opened.[15]

‘Studio Basma’ Seizes on a Telephoto Opportunity

Basma Fares, a Yemeni in her 20s, has family roots in Hadramawt, although she was born and raised in Saudia Arabia. When she was compelled to leave the kingdom in 2018, she decided to take a risk and set up her own business in Mukalla.

“That was the first time I visited Yemen,” she said. “I had no idea how the situation was, but I focused on achieving my dream there, no matter [what], and on not giving up and surrendering to failure, which would haunt me for life.”

Fares was already a keen amateur photographer, but when she moved to Yemen, she decided to turn her hobby into a profession. She opened Studio Basma using a family loan of $1,000, which she has since repaid out of her profits. Fares focused her business on female clients, taking photos and videos at women’s events and home gatherings, as well as photos of babies and children. She also worked in product photography. Fares was able to expand by using her profits rather than borrowing money.

At first, Fares had difficulty finding services for printing, and places from which to buy photo albums and photography equipment. However, she turned these obstacles into an opportunity and began offering these services and products herself, expanding her activity to printing photos and selling albums. She currently employs six women who work in photography, editing and printing. Employing only women has allowed her to secure a female customer base since many women prefer to deal with women.

Fares hopes to expand her business to other parts of Yemen, but said that even if she is offered the chance to work abroad, she will stay in Yemen “because there are great opportunities that must be seized.”

Fares said that access to loans for youths to support their creative projects, such as photography, would help them find jobs and become small business owners, adding: “At the beginning, I sought to turn my passion and hobby into a job opportunity, and now I run my own business in the field I am fond of.”

‘Café Shawa’ Makes Space for Women in Mukalla

When returning expatriate Farea’a Ahmad Badokhan was opening her new café in 2016, purchasing equipment and supplies from abroad was still the only option available.

Badokhan returned to Yemen in early 2016, a year after the war erupted, due to measures limiting job opportunities for non-Saudis in the kingdom. “It was not clear how the situation was in Yemen, but I decided to return because I had to work,” she said. “I returned to Yemen even though I was not familiar with it, since I was born to a Saudi mother and grew up in the kingdom.” Badokhan, who holds a degree in business management from King Faisal University, worked in Saudi Arabia as a secretary and administrative assistant, and also in the fields of quality management and marketing.

Badokhan opened Café Shawa in the center of Mukalla’s women’s market after realizing that the city didn’t have a single café for women. The café offers hot and cold beverages, Arabic and Western food, and includes a library. She funded the project herself with help from her family, but furnishing and stocking the café was expensive. “We had to import many resources from abroad, like furniture, equipment and raw material for beverages and food as they are not available in the local market,” she said. “This posed a challenge and was also costly.”

Badokhan said that opening the café had been difficult from the start. Her first challenge was the lack of qualified and trained employees. However, given her experience in business management, she trained the employees herself to provide proper services to her customers. In time, the café gained fame not only for being the first women-only venture of its kind in Mukalla, but also for the quality of its service.

Challenges were not limited to just opening the café; there were also difficulties keeping the business running due to fluctuating exchange rates, having to pay rent in hard currency and lack of access to basic services such as electricity, especially in summer. The concept itself also became an issue. Mukalla society did not easily accept the idea of the café at first and a number of rumors spread regarding its reputation and the purpose behind it. However, this attitude changed with time.

Badokhan said she believes the café meets an essential requirement for women in Mukalla, where public spaces are often dominated by men meeting to chew qat. She noted that the café’s profits were not as high as she had expected given the size of her investment, but that she has been studying ways to expand her business.

The challenges faced by Badokhan have been echoed across Mukalla’s commercial sector, from small enterprises such as hers, to larger endeavors in the manufacturing and production sectors.

Even though the security situation in Mukalla is good compared with other cities in Yemen, it still suffers from difficulties arising from the conflict. The depreciation of the rial and prices of oil derivatives pose persistent challenges, and restrictions to internal travel make it difficult for business people to meet to make trade deals.[16] Although commercial flights have returned,[17] the suspension of international flights at Al-Rayyan Airport is also a major obstacle for the commercial sector.[18] Poor electrical supply causes regular and prolonged power cuts that delay production and result both in wasted time and higher production costs incurred by expensive alternative power supplies.[19] Another common complaint from business owners is that qualified labor is very rare, and even qualified employees often lack professionalism and commitment.[20]

How to Help Bolster SMEs in Mukalla

Even while much of the wider economy in many areas of Yemen has been devastated during the war, at least 140 new businesses[21] that have been founded and managed to grow in Mukalla from 2018 to 2020 represent the resilience of the entrepreneurial spirit in the city. The jobs they bring also help create alternative employment options for youth in the city, many of whom otherwise have little choice but to sign up for the local military forces for the salary.

Being the capital of Hadramawt and the largest city in the east of Yemen, Mukalla is also a hub for international non-governmental organizations in the area, which spend and provide jobs locally, helping to boost the level of disposable income in circulation and support the local business environment.

Achieving peace in the country is the most crucial step in stabilizing the general economy and restoring public services across the country, and Mukalla is no exception.[22] However, in the absence of this, there are still opportunities for local socio-economic progress. Until now, entrepreneurs in Mukalla have been largely left to fend for themselves. The city lacks a cohesive plan to best exploit the money and expertise from returning expatriates and has failed to provide financial, procedural, and advisory facilities.[23]

Financial institutions can also develop their activities and services to help foster promising entrepreneurial ventures. Small projects face obstacles related to financing, as many instruments available to them are expensive or require sizable guarantees that price many would-be business owners out of the market. Few financing institutions provide advice to these emerging projects that might help them better navigate the intricacies of acquiring the necessary capital to get off the ground.[24]

Many of the returning expatriates are bold and well-trained, and willing to take the kind of calculated risks essential to succeed in business. All they require is access to capital and business advice to allow them to realize their potential contribution, both to the economy of Mukalla and for the country more broadly.[25]

Nabhan Abdullah bin Nabhan is an activist and researcher interested in Yemen and Gulf issues. He is currently doing an MA in Public Policy and Global Affairs at the American University in Cairo. His writings have appeared in al-Madaniya magazine and other regional and international publications. Nabhan is a fellow with the Sana’a Center’s Yemen Peace Forum.

Mukalla’s Arts & Culture Comeback After AQAP

By Shroq Al-Ramadi

When Al-Qaeda entered the city of Mukalla in April 2015, the cultural and artistic movement froze. Artists were intimidated, writers were muzzled, and performances were banned. Cultural visionaries and artists were singled out and targeted by AQAP. Today, five years after Al-Qaeda was forced out of Mukalla, art is slowly making a comeback. “Most of our work was on near-zero budgets to the point where we had to use the same banner 15 times,” says Shaima bin Othman, who co-founded the Meemz Arts Initiative.

Meemz was launched in 2018 under the theme “Art Returns” with the objective of promoting arts and artists and re-introducing them to the job market. Since then the organization has held more than 17 events, including workshops to empower artists and teach graphic design, film-making camps, karaoke events, and oud playing. Bin Othman, the young Hadrami woman, sees her role as two-fold. First, to resurrect the arts scene post Al-Qaeda. Second, to help break the long pattern of male dominance of local arts. Bin Othman hopes that, along with other women in Mukalla, arts can play a role in reducing gender segregation in the city.

Another group, the Takween Cultural Club in Mukalla, founded in 2017 by six young women in their late teens and early 20s, is also helping to break gender barriers (Full Disclosure: I am one of the founders). The club, which started as an informal group to teach school children, has since expanded to include both male and female artists, who can collaborate and work with one another across gender lines. The club has hosted poetry readers, book groups, training sessions, and film viewings all with the aim of reviving Hadramawt’s cultural and artistic heritage.

However, there are still challenges. Even though AQAP fled Mukalla in early 2016, there are still remnants of extremist ideology in the city and not everyone is happy about mixed gender events. In 2019, for example, young people from the dance group, Wax on Crew, were arrested by local authorities for engaging in so-called “extraneous practices.” Authorities forced the dancers to sign pledges to give up hip-hop performances. This was later revoked following a local outcry, and the dancers were subsequently invited to perform at a government-sanctioned ceremony.

The Year Without Art

When Al-Qaeda began its rule in Mukalla in 2015, it initially attempted to govern through a front group, calling itself the “Sons of Hadramawt.” It was always clear, however, who was in charge. Al-Qaeda banned street art and removed any public depictions of women, including billboards and cardboard cutouts in markets and shops. The group also launched a broad campaign to demolish Sufi shrines, which represent a branch of Islam they considered a form of religious heresy. To help with this, Al-Qaeda formed the Al-Hisbah Authority (religious police) which, among other things, prepared lists of sites to be demolished. One of these, the famous Mausoleum of Yaqub, was destroyed in 2015. Al-Qaeda exhumed graves, plundered the mausoleum, and then blew up the shrine. The explosion caused extensive damage to the surrounding houses. The Mausoleum of Al-Mahjoub and the Mausoleum of Bazara’a Mosque were later destroyed as well.

Al-Qaeda also banned Mawlid celebrations for the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad, as well as the accompanying haḍra lectures, which discuss the life of the Prophet and are often broadcast via loudspeaker in mosques, on the pretext that these were an unacceptable Sufi heresy. Many in Hadramawt worried that Al-Qaeda’s actions would not stop there, but that the group would eventually ban anything they considered heretical, including many local religious practices such the al-khatayim, which celebrates completing a reading of the Quran, and is held throughout Hadrami cities during the month of Ramadan. Instead, AQAP disseminated religious and jihadist hymns, while banning wedding parties, art exhibitions, theatrical performances, and international book fairs and seminars.

Not surprisingly, there was little local resistance to Al-Qaeda’s crackdown on the arts. Some artists withdrew from public life, attempting not to draw attention to themselves. Others traveled abroad or abandoned their art during that period. “The year under the rule of Al-Qaeda was terrible,” Saeed al-Jariri, a Yemeni poet who fled to the Netherlands after receiving threats against his life, told me via text message. “The year under Al-Qaeda’s rule created an intellectual base within society that looks down upon creativity, and where creative people’s morality and values were defamed, overshadowing the fact that he/she reflects aesthetics of morality and values that elevate humankind and overcome the monstrosity that dwells in him/her.”

The Return of Culture

Hadrami culture, through the poems of Hussein Al-Mihdhar or the songs of Karama Mirsal, is widely known in countries throughout the Middle East and Asia, and its return is rightly celebrated. It has distinctive visual arts, dance, folk stories, songs, and the Hadrami “Dan” cadence. During the 1960s, Hadramawt was characterized by cultural diversity and creativity in various spheres, particularly theater. Over time, the theater was transformed from a private enterprise to a more official status, with performances supported and sponsored by the then-ruling sultan. Additionally, book fairs and publishing houses grew to become a significant aspect of cultural activity.

According to novelist Saleh Ba’amer, the 1980s were a period of cultural prosperity in Hadramawt and the south as a whole, despite the political conflict in that decade. He said Ali Nasser Mohammed, the former president of what was then South Yemen, contributed to the prosperity and flourishing of culture in a way that kept pace with the economic, political and social reality. This included festival performances that were widely popular and toured internationally.

Hadrami culture is also apparent abroad, among the notable examples being India and Indonesia. Hadrami migrants traveled through much of the world, particularly in Asia, bringing local culture with them wherever they went, as British explorer Sir Richard Burton took note of in the 19th century: “It is generally said that the sun rises not upon a land that does not contain a man from Hadramawt.” Those who returned to Hadramawt brought other customs back with them. For instance, the sarong is the prevailing clothing style in the coast and valley of Hadramawt. There are also many borrowed words used throughout Hadramawt, such as barouta bread, shitni peppers and oush’ar, an Indian spice, which are indulged by Hadramis in their daily meals. These foods are originally from India and have become, over time, an integral part of Hadrami cuisine.

In the 1990s, cultural activities were further shaped by political and ideological trends. This time, cinemas were closed, cultural activities were curtailed and publishing houses were restricted under communal and religious censorship. Even the limited role of the Ministry of Culture and Information was further reduced due to budget cuts.

Nonetheless, Hadramawt in general and Mukalla in particular held artistic and cultural events that reflected Hadramawt’s rich and distinctive heritage at May 22nd celebrations in 2005 that marked 15 years since the unification of Yemen. The highlight of the event was “A’aras Al-Juzur,” an operetta showcasing beautiful costumes and songs, and telling the story of how Yemeni lives have changed while also reviewing Yemen’s history of accomplishments and battles for victory and unity. In 2008, Mukalla hosted its first international book fair with 80 local and Arab publishing houses participating from Gulf states, Syria, Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan. Intellectuals and artists continue to write, publish, revive cultural and artistic seminars in the region and to celebrate civilization.

It is this history that groups like Meemz and Takween are hoping to build upon as they attempt to bring back a rich and diverse art scene to Hadramawt.

Shroq Al-Ramadi is an architect, social and cultural entrepreneur, and a fellow with the Sana’a Center’s Yemen Peace Forum. She is also a researcher at Yemen Polling Center, and co-founder of Takween Cultural Club.

Dueling Mahri Scions Reveal Gulf Competition in Eastern Yemen

By Casey Coombs

On June 6, Abdullah bin Issa al-Afrar, a local politician and scion of the last Sultan of Al-Mahra and Socotra, announced on Twitter the purchase of a 40-meter ferry boat to shuttle passengers between Yemen’s easternmost governorates of Al-Mahra and Hadramawt and the archipelago of Socotra in the Arabian Sea.

Named Socotra Dream, the air-conditioned ship can transport up to 300 passengers plus vehicles and merchants’ cargo, offering residents and traders on the isolated islands a safer alternative to the rickety fishing vessels and smaller passenger boats typically used to make the days-long, 500-kilometer voyage to and from the mainland. A one-way trip on the Socotra Dream would take roughly 24 hours.

The ferry is the first of its kind in Al-Mahra and Socotra, and figures into Al-Afrar’s dream of reviving an autonomous region similar to the dynastic Sultanate of Qishn (in Al-Mahra) and Socotra that his late father ruled until it was annexed by the Marxist state of South Yemen in 1967. However, since the escalation of Yemen’s civil war in March 2015, Al-Mahra and Socotra have been caught in an intense Gulf power struggle over the two governorates that pits Omani-backed groups against those supported by Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Al-Afrar’s story is symbolic of this wider struggle.

In his tweets announcing the new ferry service, Al-Afrar praised the late Omani leader, Sultan Qaboos bin Said, for putting up most of the funds to purchase the Socotra Dream. The hat tip is noteworthy, as Al-Afrar had a falling out with Muscat after he endorsed the June 2020 armed takeover of Socotra by the pro-secession Southern Transitional Council (STC), which is backed by Oman’s rival the UAE. Oman has since supported a campaign to undercut Abdullah al-Afrar’s political influence by backing his distant cousin, Mohammed bin Abdullah al-Afrar.

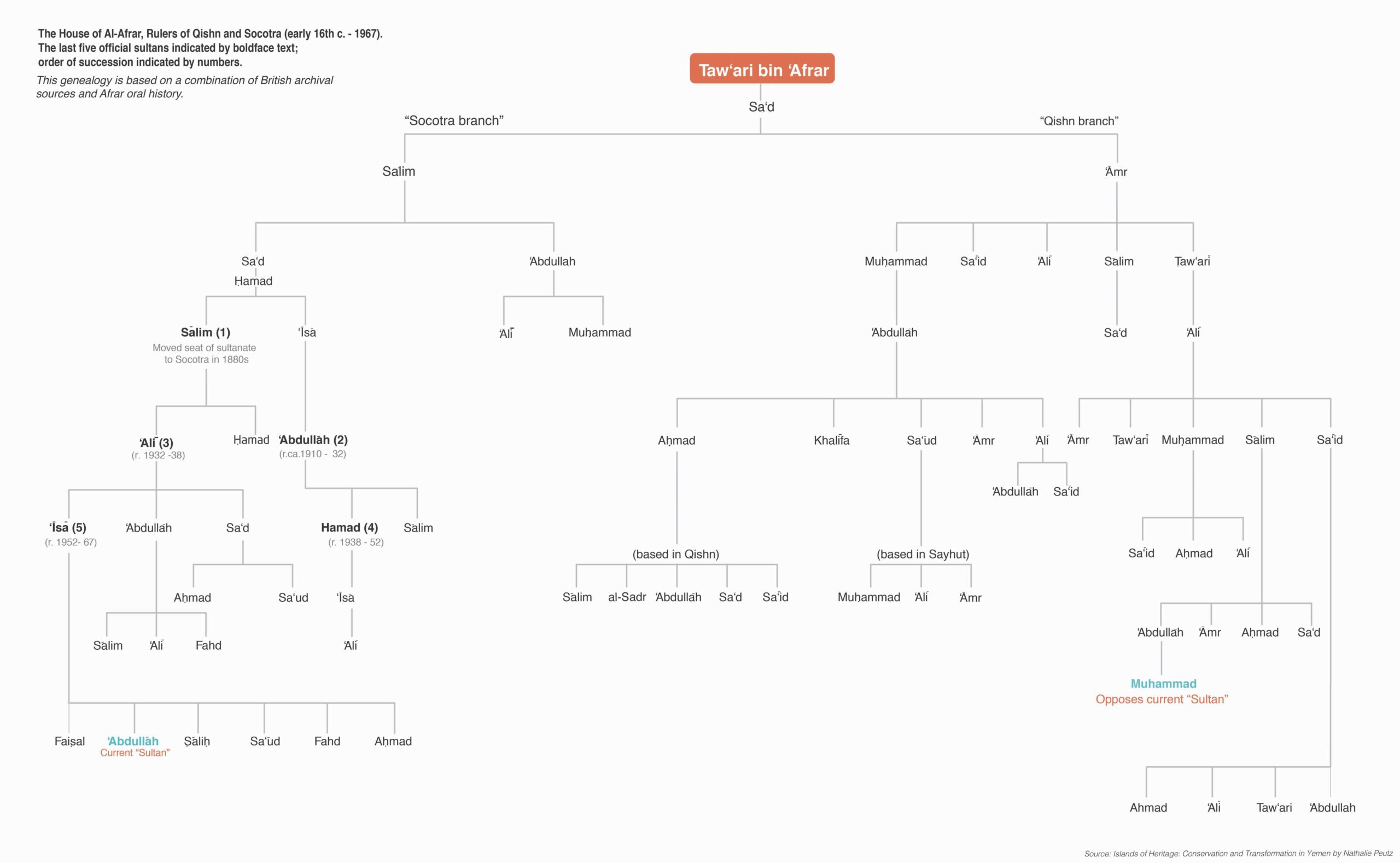

Abdullah and Mohammed come from different branches of the dynastic Al-Afrar family that ruled the former Sultanate of Qishn and Socotra from the 16th century until the formation of the now-defunct People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen in 1967. Like most dynasties, the house of Al-Afrar has internal divisions, particularly when it comes to political issues. Two distinct branches of the family have existed since at least the 1880s: the Socotra branch, where the last five ruling sultans (including Abdullah’s father) resided, and the Qishn branch, based in and around the coastal town of Qishn on the mainland in Al-Mahra. Mohammed belongs to a minor offshoot of the Qishn branch in the nearby town of Itab, while Abdullah hails from the Socotra branch and remains popular on the island. The two main branches have internal divisions of their own, as much of the Qishn wing still supports Abdullah to this day.

In 2012, when Abdullah was tapped to lead a post-Arab Spring political body called the General Council of the Sons of Al-Mahra and Socotra, both branches of the Al-Afrar family accepted him as their representative. Splitting his time between his then-home in Saudi Arabia and eastern Yemen, Abdullah presented himself as a middleman among the governorates’ competing powers, cultivating the style of popular consensus that underpinned the former sultanate.

However, as the current civil war has dragged on and the political landscape has become more polarized, Abdullah has struggled to maintain his broad political appeal and has even faced political competition from two of his five brothers. One of them, Fahd, sought Abdullah’s seat with the backing of Al-Mahra’s prominent bin Ashur family between 2013 and 2016. In 2017, when Abdullah played a role in rejecting Emirati military inroads into Al-Mahra, the UAE unsuccessfully backed another brother, Faisal, for Abdullah’s position before withdrawing most of its support from the governorate. The same year, Saudi Arabia refused to renew Abdullah’s travel documents to the kingdom, where he had been living at Riyadh’s invitation for much of his life. Shortly thereafter, he took up residence in Oman and sided with Al-Mahra’s Oman-backed protest movement opposing the Saudi-led coalition’s military presence in Al-Mahra. Oman granted him citizenship and patronage privileges, including the ability to sponsor much sought after Omani entry visas and residency permits.

This arrangement held until June 2020, when the UAE-backed STC wrested control of Socotra’s capital from Yemen’s internationally recognized government. Saudi troops stationed on the island offered no resistance. It marked the first military battle in the island’s modern history and stoked fears that Riyadh might allow a similar coup to take place in Al-Mahra.

Abdullah, seeing a path to restore his standing on the island, shifted loyalties once again and endorsed the takeover. On July 10, the Al-Mahra-based Qishn branch of the family, which opposes Saudi and Emirati influence in Socotra and Al-Mahra, signaled their rejection of Abdullah’s decision by appointing Mohammed as their representative. Following suit, five months later, on December 28, 2020, a bloc of anti-Saudi members of the General Council of the Sons of Al-Mahra and Socotra elected Mohammed as head of an Oman-backed breakaway faction of the council.

Since then, the two Al-Afrars and their Gulf patrons have carried out competing influence campaigns claiming to be the true representatives of both the family and the general council. On February 1, Mohammed presided over a meeting of the council in Al-Mahra’s capital Al-Ghaydah, stressing the need to maintain the security and stability of the governorate during the “difficult circumstances” it was experiencing.

Ten days later, Abdullah held a public meeting in Al-Ghaydah attended by hundreds of supporters carrying banners rejecting the election of Mohammed. Critics of Abdullah have framed his latest shift as a betrayal of his homeland in exchange for Saudi largesse, which has over the years included Saudi passports, housing and other support for him and his family, and a Saudi-funded battalion referred to as the “Sultan’s force” in financial documents.

How the Socotra Dream ferry service will factor into the ongoing Gulf power struggle remains unclear. It could help bridge the divide between the polarized local populations that have a shared history, or it could be used as a tool of further division if politicized. The aptly-named boat seems certain to boost Abdullah’s standing on the isolated archipelago, which may have been his dream all along.

Casey Coombs is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies and an independent journalist focused on Yemen. He tweets @Macoombs

Socotra: A Paradise Divided

Photo essay by Quentin Müller

When the ongoing Yemeni conflict escalated in 2015, no place in the country felt farther from the frontlines than Socotra governorate. Indeed, this four-island archipelago – of which the main island, Socotra, lies almost 350 kilometers southeast of the Yemeni mainland in the Arabian Sea – has existed somewhat apart from the wider world for much of its history.

The name is thought to originate from Sanskrit and mean “island abode of bliss.” More than one-third of the plant species that grow in the interior mountains and coastal plains are unique to the island. The population, with historic ties to the Mehri of eastern Yemen, today stands at some 60,000 people, with livelihoods primarily in small-scale fishing and farming-related activities.

By 2018, however, the political crises and conflicts of the mainland began landing on the island. The first major incident came when the United Arab Emirates deployed military aircraft and troops to Socotra. Though they subsequently withdrew, a Saudi military presence became a permanent fixture on Socotra. Yemenis displaced from frontline areas on the mainland also began trickling onto the island in search of safety. Then, in an unprecedented escalation of violence for the governorate, clashes between forces loyal to the internationally recognized Yemeni government, and those affiliated with the Southern Transitional Council (STC), broke out in April 2020, involving tanks, artillery and heavy weapons. While the fighting subsided, the STC subsequently seized control of the capital, Hadibo, and has had effective control of the governorate since.

In the following photo essay, journalist Quentin Müller, who visited Socotra in April this year, gives us a glimpse of both the island’s beauty and the ways in which the war has begun to divide its people.

The Dragon Blood tree is heavily dependent on the monsoon rains, which sweep through Socotra from June to September. The tree’s unique umbrella shape allows its leaves to maximize capture of the moisture in the air. However, shifting rain patterns due to climate change is likely to negatively impact the Dragon Blood trees, which are already classified as “vulnerable to extinction.” // Sana’a Center photo by Quentin Müller

According to Abdullah, a community leader among the Hudaydis in Socotra, more than 110 families from Hudaydah are now living in cramped conditions on Socotra. Many of the men work as day laborers. The displaced mainlanders have not always been welcomed, however, with some Socotris blaming them for a variety of social and political problems. // Sana’a Center photo by Quentin Müller

Hudaydah, 30 Months on since the Stockholm Agreement: A Report from the Frontlines

By Salam al-Harbi

In December 2018, the internationally recognized Yemeni government and Ansar Allah (the armed Houthi movement) signed a UN-sponsored agreement in Stockholm to halt the fighting in Hudaydah. Although the battles stopped and frontlines between forces loyal to both parties are relatively stable, several entrances to the city are still closed. The most important of these entrances is the Kilo 16 route, east of the city. The northern entrance toward As-Salif is now the alternative route to enter Hudaydah but it extends the trip from Sana’a by roughly 45 kilometers.

Along the northern route, there are several military sites that make the city look like it’s ready for war or war has just ended. There are large barriers made up of cargo containers filled with sand, while a local told me the area was also scattered with landmines. The main barrier is made up of two adjacent rows of containers. This is in addition to dozens of trenches dug on the main road at regular intervals, which are concentrated in As-Salif, 10 kilometers north of Hudaydah city.

There is barbed wire on both sides of the road to prevent citizens from reaching the mined areas. According to local citizens I spoke with, some Houthis have been killed when they wandered into the minefields.

On my way to Hudaydah from Sana’a, I saw a number of giant trucks and tractor trailers. They leave Sana’a empty and return loaded with different goods from Hudaydah. Many of these trucks carry fuel containers. But they drive recklessly and quickly, and there are frequent accidents along the road between Sana’a and Manakhah, a mountainous area roughly halfway to Hudaydah.

On the day I headed to Hudaydah, two trucks had flipped due to poor loading and unsafe driving. One of them was loaded with wood. The other truck was loaded with bags of wheat from the World Food Programme, which spilled onto the road blocking traffic. My friend who traveled on this road a few months earlier noted sarcastically: “It seems the siege tightened on the Hudaydah Port as I haven’t seen the road this crowded with trucks for decades. It was never this crowded up until 2020.”

Typically, there is one truck for every ten or twenty passenger vehicles on the road. But in June 2021, by my unofficial tally, somewhere between a third and a half of all traffic between Hudaydah and Sana’a were cargo trucks. When traveling at night, you can see the bright lights of these trucks along the curves of the mountains of Manakhah and Al-Haymah, which helps indicate your location from the mountain as you ascend on the unlit road in the pitch-dark night. You can also count dozens of cargo trucks queuing to enter the oil company in the area of Sabaha, at Sana’a’s western entrance.

But for all the traffic between Hudaydah and Sana’a, there isn’t a single gas station on the road that will sell you fuel for the official price of 8,500 Yemeni rials (YR) per 20 liters. Instead gas stations sell it for between YR 11,500 and YR 12,000, which is the price of the commercial fuel set by the company weeks ago.

Approaching Hudaydah, there are a number of checkpoints where Houthi fighters inspect people’s identity cards and inquire why they’re visiting the city. In Bajil, 50 kilometers east of Hudaydah, the enormous growth of the city can be seen, as many of Hudaydah’s merchants moved there in 2018. Bajil’s streets are full of money exchange and money transfer shops and new Houthi fighters for the western front are trained in the surrounding area.

The first thing one notices in Hudaydah is the presence of Houthi slogans. They’re on the fence of the General People’s Congress (GPC) headquarters and plastered on walls throughout the city. Along Sana’a Street, the most important street in the city, the Houthis have changed the name of the Al-Alfi Hospital, which was named after one of the Yemeni army officers who tried to assassinate Imam Ahmad in 1961, to the Center of Martyr Al-Sammad, after former Houthi president Saleh Ali al-Sammad, who was killed near Hudaydah in an Emirati drone strike in 2018. This move is part of the Houthis’ efforts to change the identity of the city. They’ve also replaced imams and preachers with Houthi loyalists.

Loudspeakers in mosques now air the speeches and lectures of the movement’s leader, Abdelmalik al-Houthi, and there are also loudspeakers installed in the main intersections of the city for the same purpose. Employees and young men are pressured to attend special “cultural” courses held by the movement. Hudaydah’s residents are mainly Sunni but the Houthi courses are based on a Shi’a doctrine, which promotes the Hashemite lineage’s exclusive right to governance.

An extreme heat wave, with temperatures rising above 40 degrees Celsius, forced me to stay in my air-conditioned hotel room all day. Outside hotels, however, most of the city’s residents have no escape from the heat. Anyone with an air conditioner in their home has to pay a premium of around YR250 for the state-generated power – which cuts out frequently – and YR350 for the privately-generated power for each hour of operating the AC. The AC consumes an average of one kilowatt of power per hour, so if it’s on for only ten hours per day, the electricity bill for AC alone would be around YR105,000 a month (around $177), which is far greater than the income of a typical family in Hudaydah.

Sometimes, the electricity is on for only an hour during the day and an hour at night. The official excuse is lack of fuel. Most families are not even able to keep water cold in the refrigerators, so they purchase ice cubes from the market.

In 2018, Hudaydah was practically a ghost town due to the intensity of the fighting, which caused many residents to flee. Those who can afford it have largely remained outside Hudaydah, but the poor have no other options. Beggars in the city used to be children and the elderly, but now young women are asking others for help. When only the poor remain, that help is nowhere to be found. Hudaydah used to be a tourist destination for Yemenis, but now hardly anyone risks the trip.