I escaped from Yemen because of the war, and you want me to die here in Amman because of the laws in Jordan?

Introduction

The humanitarian consequences of the war in Yemen are devastating, and reach far beyond the country’s borders. Ever since Saudi Arabia launched its military campaign against the Houthi movement in northern Yemen in March 2015, nearly 4 million people have been internally displaced.[1] An additional 600,000 Yemenis have fled abroad, primarily to Egypt, Djibouti, Somalia, Malaysia and Jordan.

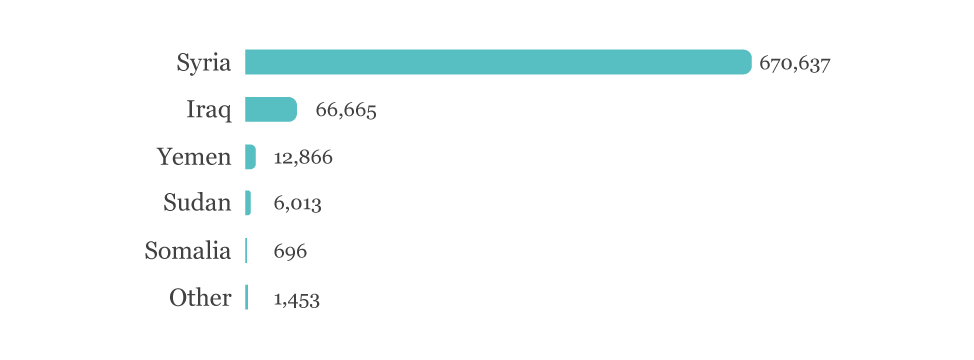

This policy brief examines the status of Yemeni migrants in Jordan, in particular those whose residence is not legally sanctioned, and offers recommendations on how to address the challenges facing these communities. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR),[2] Jordan was hosting 13,727 Yemeni asylum-seekers as of March 2021, in addition to over 700,000 refugees from other countries, mainly Syrians, Iraqis, Sudanese and Somalis. According to the last national census in 2015, the Jordanian government estimated that approximately 32,000 Yemeni nationals resided in Jordan.[3] Many Yemenis have not registered with the UNHCR, as they have acquired residency permits as students or through their employers, and others have not normalized their status. The gap between the number of Yemenis in Jordan and the number of Yemenis registered with the UNHCR can be partially explained by Jordan’s exclusionary asylum policies. Since late 2019, Jordan has urged the UNHCR to stop registering new asylum-seekers. Yemenis who arrived in Jordan after 2019 cannot apply with the UNHCR for asylum, obtain legal status or access humanitarian assistance.

Many Yemeni asylum-seekers in Jordan, particularly those who arrived after the outset of the conflict, thought their stay would be temporary, based on an expectation that the war would be short-lived. Moreover, many Yemenis in Jordan were not aware they could register or sought not to register with UNHCR in the first few years of the war. While many Yemeni migrants’ aims and outlooks have changed since 2015, their status remains precarious.

This policy brief relies on semi-structured interviews conducted in Arabic with 43 Yemeni asylum-seekers in Amman – women and men – aged 16 to 60 years old. Most of the interviewees are not recognized as refugees by the UNHCR. They had middle-class backgrounds in Yemen, but their social and economic situations have become precarious in Jordan. Pseudonyms have been used for all interviewees to protect their privacy.

The policy brief is based on research into the reception of foreign populations in Jordan and the country’s relationship with “otherness”. The humanitarian system in Jordan as well as academic migration studies have mainly focused on Syrian refugees since 2011, due to the fact that 6 million Syrians currently reside in bordering countries[4]. As a result, academic and humanitarian studies on migration in Jordan neglect refugees from minority groups, such as Yemenis. Few humanitarian reports have been published on Yemeni asylum-seekers in Jordan,[5] and these mainly address their legal status, education and access to UNHCR services and humanitarian aid.

This policy brief contributes to new research focusing on Yemenis and their mobility since 2015.[6] It discusses the exile of Yemenis and movement restrictions on Yemenis migrating abroad. Multiple studies are being conducted in parallel, with new work on the political mobilization of Yemeni political elites in exile[7] and gender, ethnic and identity reconfigurations of Yemeni refugees in Djibouti.[8]

This policy brief contributes to this new vein of research by exploring the restrictions of movement that Yemenis experience in their exile. It also discusses the conditions of their exile in Jordan, characterized by precarious financial circumstances and isolation due to exclusionary national policies.

Differing Statuses and Regional Boundaries Among Yemeni Communities in Jordan

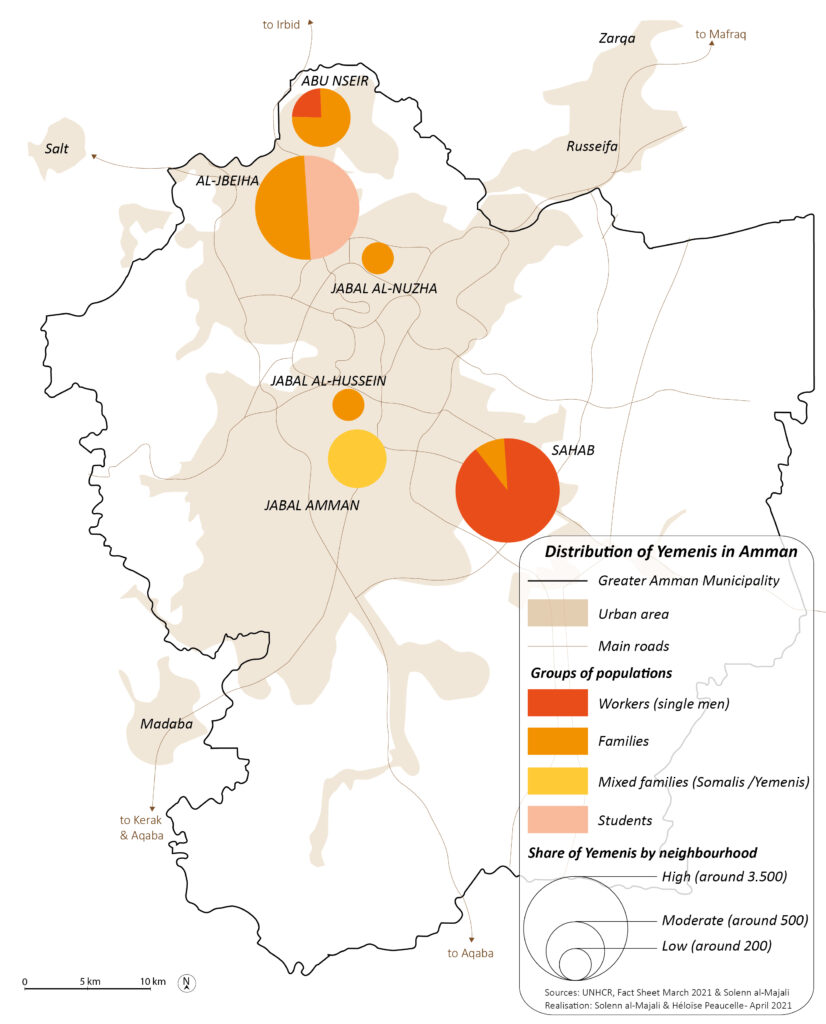

Small Yemeni communities existed in Jordan prior to the war, particularly in Amman and other governorates such as Maʿan and Irbid. These communities are largely composed of students from Hadramawt governorate who study at the Jordanian University in Amman or at Yarmouk University in Irbid, as well as restaurateurs and owners and managers of other companies. Yemeni laborers, mainly from the governorates of Taiz and Ibb, work in industrial areas such as Marka and Sahab, to the east of Amman. Prior to the conflict, it was common for Yemenis from northern governorates to travel to Amman for medical treatment.[9] Yemeni patients often seek treatment abroad for cancer, heart disease, kidney failure and invasive orthopedic and neurological disorders, mainly to Egypt, Jordan and India.

Currently, most Yemenis in Jordan reside around Al-Jbeiha, in North Amman. The district is dotted with Yemeni restaurants established prior to the conflict. A mixed Yemeni-Somali community is centered in Jabal Amman, close to Wast al-Balad, the city center. Yemeni-Somalis are referred to as mūwalladīn in Yemeni Arabic. The derogatory term refers to all Yemenis of a multiethnic background, mainly those with East African mothers, primarily Ethiopian, Eritrean and Somali. In Jordan, most have a Yemeni father and Somali mother, and were living in Aden before the war, in particular in Sheikh Othman district and Al-Basateen neighborhood in Dar Saad district.[10] They have different social networks from other Yemeni groups in Jordan as their strong ethnic boundaries were already established in Yemen. They do not have the same work opportunities as other Yemenis (few work in Yemeni restaurants for example)[11] and live in a different area of Amman.

In addition to ethnic and regional divides, Yemeni communities hold different social statuses in Jordan, ranging from investors (though far fewer than in Egypt for example), students, middle and upper-class families, to single male workers. Both social status and region of origin play a strong role in determining where Yemenis reside in Amman. According to interviewees, Yemenis most often live in neighborhoods populated by individuals from their governorate in Yemen, where investors or businessmen are most likely to assist or employ people from their home region. In many cases this has resulted in discrimination and a deficit of trust between migrants who hail from different regions of Yemen. Political affiliation also plays a significant role: some migrants supported Ali Abdallah Saleh, while others fled from forced recruitment by the Houthis. A more comprehensive assessment of how politics affects Yemenis in exile would require additional fieldwork.

Restrictive Hosting Policies

Most Yemenis who traveled to Jordan at the outset of the Yemen conflict believed that their stay would be temporary, in particular political elites who moved to wealthy areas of Amman. Most did not register with the UNHCR, an action which would have – in most cases – normalized their residency status in Jordan but prevented them from returning to Yemen if the situation had improved. Through April 2015, Yemenis were permitted to enter Jordan without a visa and could remain without acquiring a residency permit, but since then they have needed to acquire a visa. These restrictions have made it more difficult for Yemenis to migrate, not only to Jordan, but to countries which implemented similar policies, such as Egypt.

For Yemeni asylum-seekers, the easier way to seek refuge is often to enter Jordan on a medical visa. This requires obtaining a medical report in Yemen and working with a travel agency that has an agreement with Jordanian hospitals. Although some Yemenis require health care in Jordan, most use these medical visas to legally enter and stay in Jordan for three months. During this period, Yemenis must choose whether to register with UNHCR to obtain refugee status and “legalize” their residency.

The number of Yemenis registered with UNHCR has grown as they familiarize themselves with asylum procedures in Jordan, but the resettlement process is slow and limited. Many Yemeni asylum-seekers interviewed in 2020 stated that they did not wish to return to Yemen, largely due to the prospect of political persecution and a lack of viable work opportunities. They are now waiting and hoping for resettlement by the UNHCR to a third country, such as Canada, the United States or a European country. However, less than one percent of refugees living in transit countries such as Jordan, Egypt and Lebanon are resettled in a Western country. Resettlement opportunities for Yemenis are even less common. UNHCR data on Yemeni resettlement opportunities is not available. But the fieldwork undertaken for this policy brief suggests that fewer than 20 Yemenis have been resettled since 2018, mainly in Canada and the United Kingdom. Of note, Somali-Yemenis with dual nationality may be registered as Somalis by the UNHCR, and resettled as Somali refugees.

The UNHCR asylum-seeking process is perceived differently now compared to when Yemenis first arrived in Jordan in 2015 and 2016. At that time, not only elites, but lower and middle class Yemenis were unfamiliar with UNHCR registration procedures, and many reported at first feeling too ashamed to apply for refugee status. This is likely related, in part, to Yemen hosting refugees from East Africa. Somalis constitute one of the largest refugee communities in Yemen, comprising 600,000 to 800,000 people.[12] Yemen is also the only Middle Eastern country to sign the 1951 Geneva Convention on the rights of refugees.[13] Refugee status may therefore be perceived negatively by the Yemeni population, especially in a society with very narrow social classes such as Sayyed (one who claims descent from the Prophet Mohammad), Qabīlī (tribesman) or even ākhdām (servants).[14]

Residency and Registration

In Jordan, most Yemenis register with UNHCR to obtain asylum-seeker documents, which the Jordanian government does not treat as proof of residency. Residence permits are very expensive (which is conditioned on obtaining a work permit and costs between US$600-1,000 per year), meaning cost is a major barrier to Yemenis normalizing their status in the country.[15] While Egypt hosts the largest number of displaced Yemenis (500,000 to 700,000),[16] Jordan is where the largest number of Yemenis have applied for asylum with the UNHCR, due to the lack of other options for legalizing their status. Yemenis in Egypt can also more easily acquire a residency permit because it is significantly less expensive (approximately US$6 for a six-month renewable permit).

Yemeni asylum-seekers in Jordan are not recognized as refugees by the UNHCR and governmental institutions. To obtain refugee status from the UNHCR, Yemenis must be interviewed several times to prove that they face persecution in Yemen. The UNHCR has established two procedures to determine one’s status. In the case of a prima facie process, a population is collectively recognized as refugees. 665,884 Syrians[17] obtained refugee status in Jordan without interviewing with a UNHCR officer. The Refugee Determination Process (known as the RSD process) entails case-by-case interviews. During such interviews, the applicants share their life stories and discuss reasons why they were forced to leave their country of origin. A UNHCR officer must then identify the nature of persecution, namely whether the religious, ethnic or tribal identity of a candidate prevents them from returning to their country of origin.

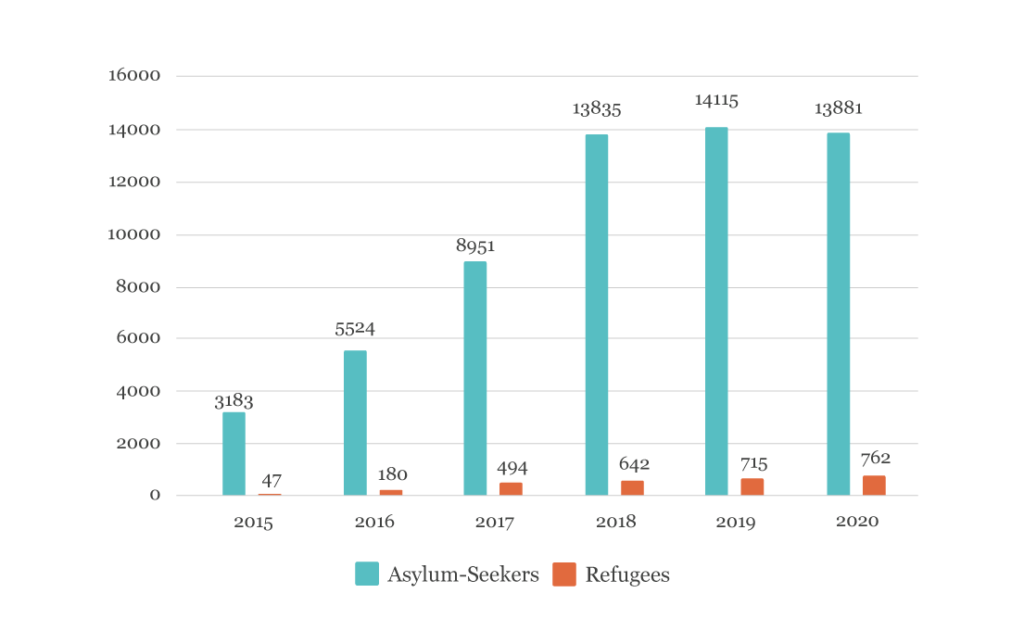

This graph displays the evolution of refugee status granted by UNHCR to Yemenis. Since 2017, the number of Yemeni asylum-seekers has considerably increased. However, the number of Yemenis granted status has remained low compared to other populations such as Iraqis, Sudanese and Somalis. Since late 2019, Yemeni citizens can no longer register with UNHCR due to the registration ban implemented by the Jordanian government. This new regulation bars new asylum applications via the UNHCR, meaning Yemenis who arrived in Jordan in 2020 or 2021 have no way to legalize their residence. One of the Yemeni respondents referred to this group as the “unknowns” (mağhūlin), because they have neither UNHCR documents nor residence permits and can be deported to Yemen at any time.

In 2020, only 762 Yemenis, who had applied with the UNHCR prior to 2019, obtained refugee status, while 13,881 are awaiting a Refugee Status Determination (RSD) interview by UNHCR.[18] The non-recognition of Yemenis as refugees is due to both internal and external geopolitical factors, and there are multiple reasons why Yemenis are not eligible for refugee status in Jordan and other countries across the region.

First, if the UNHCR recognized all Yemenis as statutory refugees, it would put political pressure on Saudi Arabia and highlight its predominant role in the conflict. Such a measure would effectively blame Saudi Arabia for the exile of Yemenis in Jordan and other countries in the region.

Second, in the early years of the conflict, Yemenis living abroad took advantage of stability in some areas of their home country to travel back and forth. However, according to the 1951 Geneva Convention, a refugee must demonstrate that if they were forced to return to their country of origin they would face persecution, that they have “a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion,” and are “outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”[19] Consequently, Yemenis who apply to the UNHCR for asylum after returning to Yemen several times have difficulty obtaining refugee status.

The UNHCR classifies vulnerable individuals according to the national, ethnic or racial origin of the applicants. It has established guidelines for more than 15 countries, but has no such framework related to asylum procedures for Yemeni citizens seeking refuge abroad. Its official position is that “as the situation in Yemen remains highly fluid and uncertain, UNHCR calls on all countries to allow civilians fleeing Yemen access to their territories.”[20]

The framework for granting status to Yemeni asylum-seekers remains unclear and is related to the suspension of forcible returns of nationals and regional refugee protection frameworks. In comparison to Jordan, Djibouti has, for instance, accepted Yemeni refugees on a prima facie basis.[21] In Jordan, UNHCR’s official position on the conflict in Yemen makes it difficult for UNHCR to conduct RSD interviews. Consequently, it places displaced Yemenis in legal limbo, which impacts their daily life and access to humanitarian and public services.

Some Yemeni interviewees asserted that they cannot return to Yemen, as Houthi forces have directly threatened them. Ibrahim, a 36-year-old man, fled from Sanaʿa after being forced to join the Houthi movement, even though he is part of a Sayyed family.[22] Ibrahim sold his home in Sana’a in 2019 in order to pay for airline tickets to Jordan, where he, his wife and newborn child currently live on his savings.[23] He later started working as a honey seller in a shopping mall to support his family.

Others Yemenis in Jordan hail from regions less affected by the conflict and have been able to return to Yemen several times. Um Maryam, a mother of three from Abyan, started to travel to and from Jordan in 2013 to escape Al-Qaeda attacks in southern Yemen.[24] She traveled several times to visit her maternal family in Yemen before settling in Jordan in 2017. Following the destruction of her home by Saudi forces, she decided to remain in Jordan. Eventually, she was granted refugee status in 2021, an eight-year delay due to her travel back to Yemen.

Access to Humanitarian Assistance

Yemenis in Jordan have limited access to UNHCR financial assistance, health services and resettlement opportunities. UNHCR classifies Yemeni asylum-seekers, and other refugees not fleeing from Syria, as “non-Syrian refugees”. Accordingly, asylum-seekers from countries other than Syria are considered secondary refugees by humanitarian institutions, in effect denying the particularities of each refugee community. Additionally, international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and the UNHCR have little information on Yemeni asylum-seekers, as less research has been conducted on their communities.

Since 2018, each non-Syrian refugee or asylum-seeker community has had representatives at the UNHCR to relay communities’ concerns. Yemeni asylum-seekers in Amman have three representatives allotted according to the neighborhoods in which they live: Al-Jbeiha/Abu Nseir, Jebel al-Nuzha and Sahab. Representation at the UNHCR presents an opportunity for Yemenis to make their concerns heard at the institutional level. Since 2018, recognized Yemeni refugees have been able to obtain monthly financial aid from the World Food Programme (WFP).[25]

Access to Labor Markets

Jordan has signed agreements with the international community to facilitate the integration of Syrians and promote development opportunities. In 2016, the Jordan Compact was established to facilitate Syrian refugees’ access to the labor market in specific sectors. However, the Jordan Compact excludes refugees from countries other than Syria, including Yemeni asylum-seekers, restricting access to governmental services and labor and education opportunities.[26] As foreigners in Jordan, Yemenis are allowed to work in specific fields, such as the construction sector, agriculture and restaurants, if they obtain work permits and have a kafeel, a Jordanian sponsor under the kafala system.[27] Obtaining a work permit is costly – about USD 600 to USD 1,000 – and Yemenis then must rely on their Jordanian sponsor. Um Tawfiq’s husband, for example, faced a range of issues with a Jordanian kafeel while working at a Yemeni restaurant in Sahab city. The kafeel seized his passport, even though such action is forbidden by law. He worked 12 hours a day and did not receive his salary several times.[28] This situation is common among refugees in Jordan, who often report exploitation and difficult work conditions.

The majority of Yemeni men interviewed for this study are working informally in Jordan as servants in coffeehouses, housekeepers, honey sellers or waitstaff in Yemeni restaurants, especially in Al-Jbeiha.[29] Other Yemenis do not work in Jordan because they do not want to work in these sectors, which are viewed negatively by society, and instead seek financial support from family members in Yemen. While remittances from the Yemeni diaspora were once almost exclusively used to support families in Yemen, the conflict appears to be changing this dynamic. Now, it is common for individuals or families to be dependent on family members who remained in Yemen. Most Yemeni women do not work in Jordan due to social gender norms and the sexual harassment that they face as foreign workers. However, many of the women interviewed expressed their desire for financial autonomy through home-based businesses and vocational training.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020, the Jordanian Ministry of the Interior has established restrictive new regulations for Yemenis. They are not allowed to hold both work permits and asylum-seeker’s documents from the UNHCR.[30] They have only two options in Jordan: either to work legally without the option of being resettled; or wait to be granted refugee status from the UNHCR, and be resettled, a process which can take 10 to 15 years. Since the implementation of these regulations, several Yemenis have been deported to Yemen during the work permit application process due to the fact that they were also issued UNHCR documents.[31] Yemeni asylum-seekers are afraid to work in Jordan lest they be deported back to Yemen, where they face the threat of new violence and persecution

Access to Education

Accessing education remains difficult for Yemenis in Jordan, as they are considered foreigners, not refugees, and must therefore prove legal residence in order to enroll their children in school. UNHCR documents proving that they are registered are not sufficient. In addition to a residency permit, registration at primary and secondary school for Yemenis requires for the children to not to have missed more than two years of school.[32] Access to Jordanian public schools is also contingent on the respective areas in which Yemenis live and the local school’s capacity to host additional students. Um Mohsen could not register her four-year-old son at school while her daughter was enrolled. She was asked for her residence permit, but she only has her asylum papers.[33] She finally managed to register him because she knew some of the teachers in the school and contacted local charities for assistance.

In comparison, access to education for Yemeni communities in Egypt is more structured. The first Yemeni school was established in Egypt in 2017 and Cairo currently hosts three private Yemeni schools, which teach a Yemeni curriculum.[34] There are no such projects or initiatives in Jordan at this time.

Yemeni Initiatives to Communities in Jordan

Yemeni diaspora communities have tried to establish initiatives to support Yemeni communities in Jordan, but domestic policy in the kingdom limits their ability to do so. Despite this, members of the Yemeni diaspora and businessmen have provided support to poor Yemeni families in Jordan via donations since 2015. For example, the Yemeni tea company Al-Kbous, which has been based in Amman since 2013, provided financial assistance to poor Yemeni families during the COVID-19 lockdown in May 2020, in cooperation with the Yemeni embassy in Jordan.

Other wealthy Yemeni businessmen based in Jordan and abroad make financial donations to needy families or students. This type of financial aid is usually organized informally via Yemeni communities, primarily over WhatsApp groups. However, these initiatives are ad hoc and unstructured.[35]

Conclusion and Recommendations

Yemenis have adapted to exile in different ways. In 2015, Yemenis in Jordan were averse to registering as refugees, but in the years since have sought to legalize their status, either through acquiring work in a sanctioned sector or by registering with the UNHCR in the hope of eventually resettling in Europe or North America.

The cost of a visa and travel dictate that middle class Yemenis are most able to find refuge in a foreign country. Once in Jordan, Yemenis of all backgrounds and socio-economic statuses are subject to policies which make acquiring legal residency and employment difficult.

Accordingly, the following recommendations are made in line with the research and presented in this policy brief:

To the International Community:

- Conduct more humanitarian and academic studies on growing Yemeni communities in Egypt, Djibouti, Jordan, Somalia (including Somaliland and Puntland), Malaysia and Sudan to shed light on their legal, financial and social needs.

- Increase resettlement opportunities for displaced Yemenis by easing the conditions for Yemenis to enter Western host countries; and increasing the opportunities for university scholarships for Yemeni students (who very often in Jordan have university degrees).

To the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and international and local NGOs in Jordan:

- Recognize Yemenis as prima facie refugees or make sure that the RSD process is conducted for all Yemeni asylum-seekers.

- Consider advocating for a policy to provide annual residency to asylum seekers and refugees.

- Increase support to Yemenis living in Jordan by offering:

- Financial assistance to cover basic living expenses, medical treatment and school fees.

- Livelihood support, such as microfinance loans and vocational training, to promote refugee-run micro enterprises and home-based businesses.

- Raise awareness among Yemenis on the school registration process and advocate for students who face difficulties registering to school.

- Advocate for anti-discrimination programs in schools to combat discrimination/racism toward Yemeni students, especially Muwalladin, and promote positive interactions between students of different nationalities.

To Yemeni Community Leaders:

- Provide opportunities for community members to connect and organize.

- Raise awareness among Yemeni asylum-seekers about their rights, the procedures of UNHCR, and available support and assistance. This could be achieved through organized workshops, for example. through workshops to inform about the procedures of UNHCR, and the rights and obligations of Yemeni asylum-seekers.

This policy brief is part of a series of publications, produced by the Sana’a Center and funded by the Government of the Kingdom of Sweden, examining Yemeni diaspora communities.

The author of this policy has also received support for her research as part of the ITHACA project, a multi-year EU-funded program aiming to raise awareness, inform the public debate, and disseminate recommendations to improve policies, empowerment, inclusion and participation related to migration.

- “Yemen Fact Sheet,” UNHCR, December 2020, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/country/yem

- “Jordan Fact Sheet,” UNHCR, March 2021, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/03%20-%20Jordan%20Mar%202021%20Operational%20Update.pdf

- “Jordan National Survey of Non-Jordanian Population,” Jordanian Government, 2015, http://www.dos.gov.jo/dos_home_a/main/population/census2015/Non-Jordanians/Non-jordanian_8.1.pdf

- “Situation Syria Regional Refugee Response,” UNHCR Operational Data Portal, 2022, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria

- Dina Balsan, Rochelle Johnston, Anna Kvittigen, “Realizing The Rights of Asylum-Seekers and Refugees in Jordan From Countries Other Than Syria With a Focus on Yemeni and Sudanese,” 2019, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/71975.pdf; “Jordan: Yemeni Asylum-Seekers Deported,” Human Rights Watch, March 30, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/30/jordan-yemeni-asylum-seekers-deported; Solenn Al Majali and Simon Verduijin, “Somalis and Yemenis of Mixed Origins Stranded and Struggling in Jordan’s Capital,” 2020, Mixed Migration Centre, https://mixedmigration.org/articles/somalis-and-yemenis-of-mixed-origin-stranded-and-struggling-in-jordans-capital/

- Bogumila Hall, “Yemeni Freedom and Mobility Dreams,” MERIP, November 8, 2021, https://merip.org/2021/08/yemeni-freedom-and-mobility-dreams/; Laurent Bonnefoy, “Revolution, War, and Transformations in Yemeni Studies,” MERIP, December 15, 2021, https://merip.org/2021/12/revolution-war-and-transformations-in-yemeni-studies/

- Marine Poirier, “This charming sheikh. Constructing and defending notability in Yemen (2009-2019),” Critique internationale, Volume 87, Issue 2, April 2020, https://www.cairn-int.info/journal-critique-internationale-2020-2-page-175.htm; Maysaa Shuja al-Deen, “The Long Shadow of War: Yemeni Diasporas Dynamics since 2011,” Arab Reform Initiative, April 2021, https://s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/storage.arab-reform.net/ari/2021/07/26151446/2021-07-26-EN-Diaposra_YEMEN_FINAL.pdf

- Nathalie Peutz, “The Fault of Our Grandfathers: Yemen’s Third-Generation Migrants Seeking Refuge From Displacement,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, June 6, 2019, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-journal-of-middle-east-studies/article/abs/fault-of-our-grandfathers-yemens-thirdgeneration-migrants-seeking-refuge-from-displacement/3BDB2FFE592AC356EAA410D8569CBEB7

- Beth Kangas, “Hope from Abroad in the International Medical Travel of Yemeni Patients,” Anthropology & Medicine, Vol. 14, No. 3, February 6, 2008, pp. 293–305, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13648470701612646

- In the late 19th century, Somali traders settled in Yemen, notably in Aden, during the period of British colonization. Most lived in the districts of Al-Ma’alla and Sheikh Othman. After the outbreak of civil war in Somalia in the 1990s, Al-Basateen became a primary place of refuge for Somali refugees and muwalladin populations returning from Somalia.

- Aisha Al-Jaedy, “Neither Yemeni Nor Foreign: Life as a Muwalladin of Hadramawt,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, January 26, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/ypf/life-as-a-muwalladin-of-hadramawt/

- Hélène Thiollet, “From Migration Hub to Asylum Crisis: The Changing Dynamics of Contemporary Migration in Yemen” in Helen Lackner (ed.). Why Yemen Matters, Saqi Books, 2014, https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01675524/document.

- Hélène Thiollet, “From Migration Hub to Asylum Crisis: The Changing Dynamics of Contemporary Migration in Yemen” in Helen Lackner (ed.). Why Yemen Matters, Saqi Books, 2014, https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01675524/document.

- For more on the ākhdām, see: Mohammed Al-Harbi, Marta Colburn, Sumaya Saleem, Fatima Saleh, “Bringing Forth the Voices of Muhamasheen”, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 13, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/files/Bringing_Forth_the_Voices_of_Muhammasheen_en.pdf

- Qabool Al-Absi, “The Struggle Far from Home: Yemeni Refugees in Cairo,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, December 18, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/12286

- Qabool Al-Absi, “The Struggle Far from Home: Yemeni Refugees in Cairo,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, December 18, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/12286

- “Jordan Fact Sheet,” UNHCR, March 2021, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/03%20-%20Jordan%20Mar%202021%20Operational%20Update.pdf

- “Refugee Data Finder,” UNHCR Statistics, 2015-2020, https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/download/?url=s9RmHF

- UNHCR, “Handbook and Guidelines on Procedures and Criteria For Determining Refugee Status Under the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees,” reissued in February 2019, https://www.unhcr.org/publications/legal/5ddfcdc47/handbook-procedures-criteria-determining-refugee-status-under-1951-convention.html

- “UNHCR Position on Returns to Yemen,” UNHCR, April 2015, https://www.refworld.org/publisher,UNHCR,COUNTRYPOS,YEM,5523fdf84,0.html

- Nathalie Peutz, “‘The Fault of Our Grandfathers’: Yemen’s Third-Generation Migrants Seeking Refuge from Displacement,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 2019, pp. 357-76, https://www.academia.edu/40015537/_THE_FAULT_OF_OUR_GRANDFATHERS_YEMENS_THIRD_GENERATION_MIGRANTS_SEEKING_REFUGE_FROM_DISPLACEMENT

- Author’s interview with a Yemeni asylum-seeker in Amman, October 27, 2020.

- Author’s interview with a Yemeni asylum-seeker in Amman, October 27, 2020.

- Author’s interview with a Yemeni asylum-seeker in Amman, March 12, 2019.

- Author’s interviews with Yemeni asylum-seekers in Amman, August 2020.

- Veronique Barbelet, Jessica Hagen-Zanker and Dina Mansour-Ille, “The Jordan Compact: Lessons learnt and implications for future refugees compact”, ODI, February 2018, https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/12058.pdf

- The kafala system is a sponsorship system in which migrant workers legally enter and stay in a host country with the support of a sponsor who employs them. The worker’s immigration status is tied to the employment contract. They cannot change jobs or leave the country without first obtaining explicit, written permission from their employer.

- Author’s interview with a Yemeni asylum-seeker in Sahab, July 24, 2020.

- In Yemeni restaurants in Al-Jbeiha, not all Yemeni workers are registered with the UNHCR. Some have been in Jordan a long time and have work permits.

- “Jordan: Yemeni Asylum-Seekers Deported,” Human Rights Watch, March 30, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/30/jordan-yemeni-asylum-seekers-deported

- “Jordan: Yemeni Asylum-Seekers Deported,” Human Rights Watch, March 30, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/30/jordan-yemeni-asylum-seekers-deported

- Dina Baslan, Rochelle Johnston and Anna Kvittingen, “Realizing the Rights of Asylum-Seekers and Refugees in Jordan from Countries Other than Syria With a Focus on Yemenis and Sudanese,” Relief Web, October 27, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/71975.pdf

- Author’s interview with a Yemeni asylum-seeker in Amman, May 25, 2020.

- Qabool Al-Absi, “The Struggle Far from Home: Yemeni Refugees in Cairo,” Sanaa Center for Strategic Studies, December 18, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/12286

- Author’s interviews with Yemeni asylum-seekers in Amman, August 2020.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية