Introduction

Since the onset of the Yemen conflict in 2014, Marib, a relatively small city that was recently home to less than 40,000 inhabitants, has received more than a million internally displaced persons (IDPs). The rapid growth of the city has changed life for native Maribis and led to a number of challenges for both the host community and IDPs, including overcrowding, over-leveraged public services, strained infrastructure, and high housing and real estate prices. In response, a flurry of initiatives to address infrastructure- and service-related issues that have long plagued Marib city have been undertaken during the conflict.

Paradoxically, the mass migration to Marib during the conflict has also increased the amount of human and capital assets available to residents in the city, making it more prosperous and a significant center of development and investment in Yemen. This will have long-lasting impacts on the governorate not only from a humanitarian perspective, but also in terms of economic development, reconstruction, and politics. Taking this into account, this policy brief aims to analyze the impact of migration on Marib – both positive and negative – in order to better tailor responses to the migrant influx and develop future solutions.

Methodology

The policy brief is guided by a review of existing research and reporting published on Yemen, Marib governorate, and Marib city, in addition to key informant interviews and discussions with subject-matter experts in the governorate. Sixteen semi-structured interviews were conducted with specialists, such as health, education, and civil society experts, officials at the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (MoPIC), as well as members of the Marib Strategic Thinking Group, a platform that seeks to achieve a greater understanding of local dynamics and propose solutions to address the core needs of residents of the governorate.

Understanding Displacement in Marib

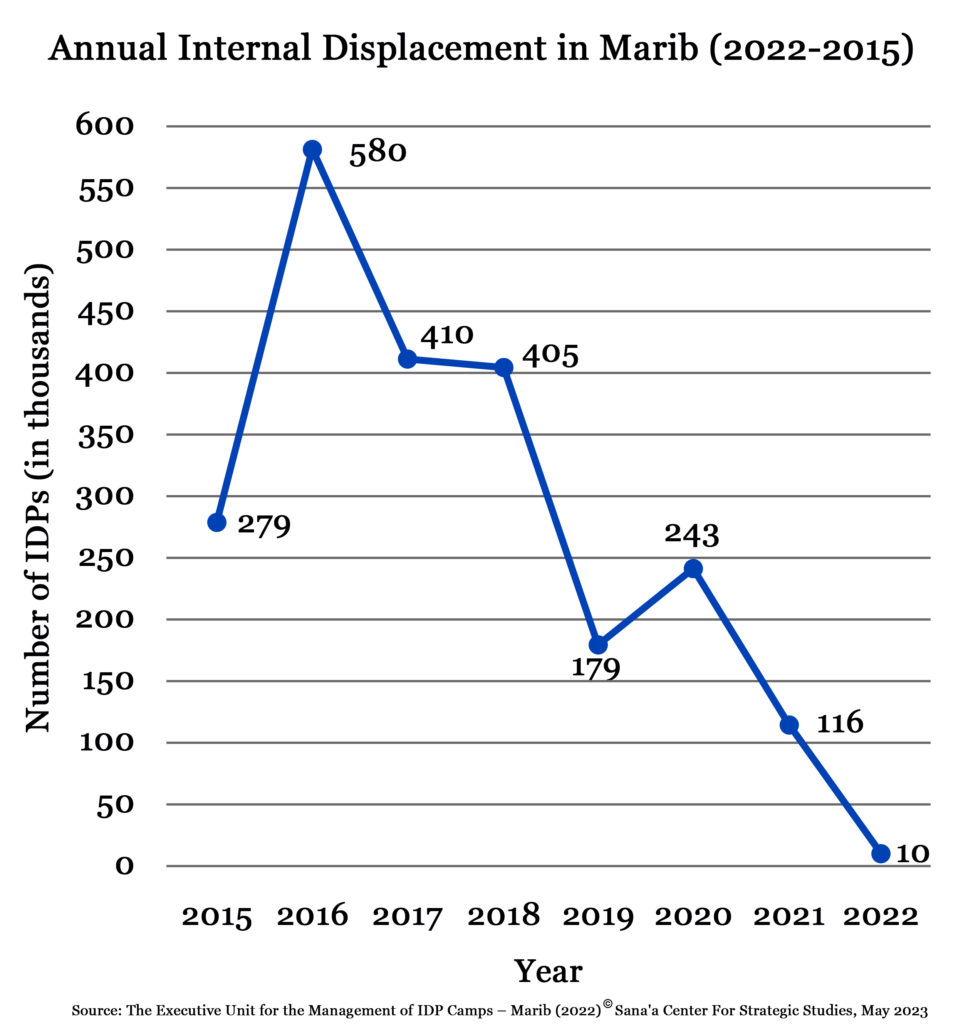

Before analyzing how displacement has affected Marib city’s host communities, it is important to understand the demographics and trends of migration. Marib city, located in an oil-rich governorate, became a preferred destination for IDPs fleeing conflict in Yemen, including many northern families and business owners who fled regions controlled by Houthi forces and felt they would not be welcome in southern Yemen.[1] The governorate’s population has grown from about 240,000 residents in 2004[2] to over 3 million in 2022, including over 2 million IDPs, according to the government-run Executive Unit for the Management of IDP camps in Marib.[3] In 2019, more than 90 percent of Marib city’s population of approximately 630,000 were estimated to be IDPs.[4]

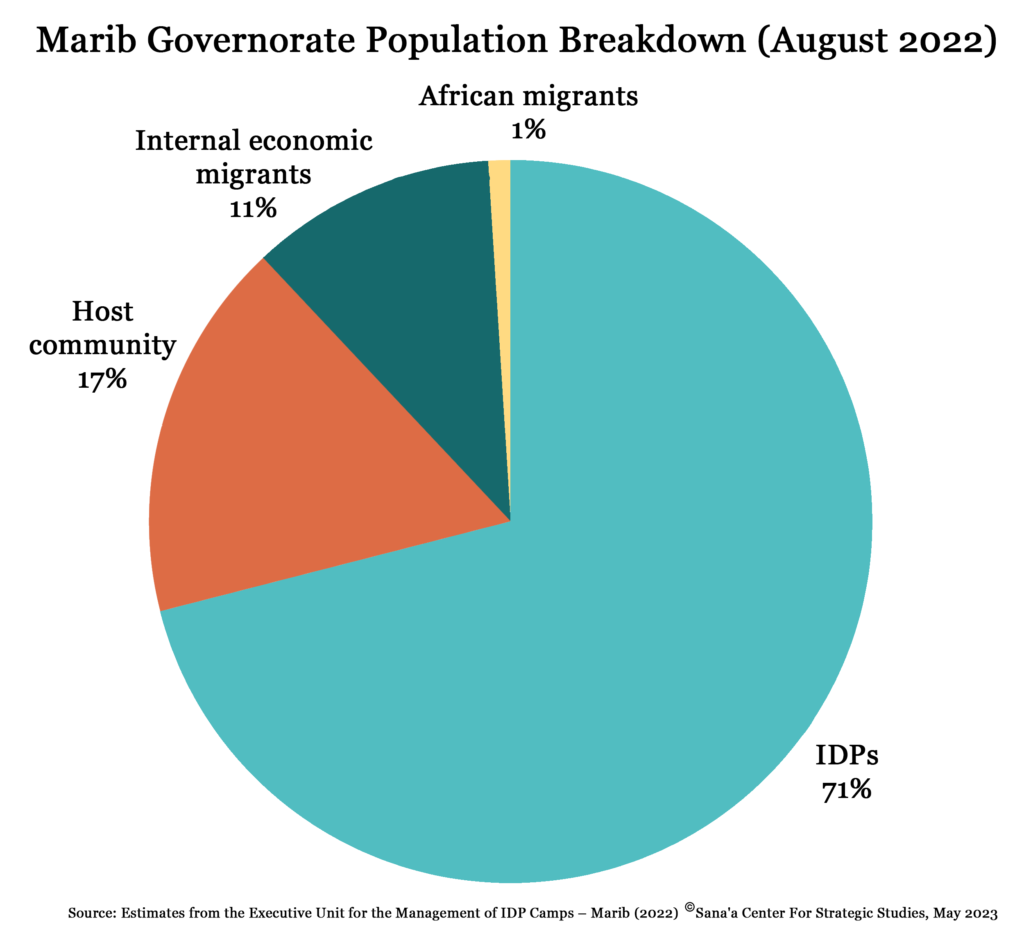

According to estimates from the Executive Unit, the governorate’s IDP population dwarfs the host community, which makes up only 17 percent of those present in the region as of August 2022. Of the more than 2.2 million displaced persons in the governorate, 13 percent live in the governorate’s 197 IDP camps, while the remaining 87 percent chose to reside alongside the host community, mainly in Marib city and along the outskirts of the city.[5] Moreover, data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Marib IDP Intentions Survey shows that most migrants are there to stay. Of the over 2,000 households sampled, 79 percent stated that they had no intention of returning to their original place of residence. Only 3 percent indicated a determined intention to return to their homes.[6] This shows that the many migration-related impacts that will be discussed in the following section are not simply wartime problems but major societal shifts that will require long-term solutions. More likely than not, Marib will be a primary area of focus for both conflict resolution and the years of reconstruction that follow any political settlement to the ongoing war.

The Effects of Internal Displacement on the Marib City Host Community

In interviews with 16 subject-matter experts, participants were asked which sectors of society have been most affected by waves of internal displacement to Marib since the beginning of the conflict. All of these experts are residents of the governorate themselves and have witnessed changes in the region first-hand. To quantify these perspectives, they were asked to rank, from 0 percent (zero impact) to 100 percent (highest impact), which sectors have been impacted the most.

In general, they identified several key areas of concern, with most agreeing that housing had experienced the biggest impact from the influx of IDPs. Respondents also highlighted strains on public services, such as in the education and health sectors, and on the governorate’s already-weak physical infrastructure. Along with these challenges, experts also identified positive developments, particularly the commercial and economic growth that has accompanied migration. The following section breaks down the top five sectors impacted in the view of experts and examines new and existing data to correlate migration trends with these observed community changes.

1. Housing

Almost all respondents identified changes in the housing market as the major issue affecting the host community in Marib city. Several pointed to skyrocketing rent costs since 2015 and constrained housing availability. Prior to 2014, the price of medium-sized apartments ranged from 30-50,000 Yemeni rials (YR) (US$150-250), while current rent prices have significantly increased, ranging between YR250-350,000 (US$222-311) in 2022.[7] Residents of Marib city are finding it increasingly difficult to pay rent as increased demand for housing drives up costs. For example, one resident claimed that he rented a two-bedroom flat in Marib city for nearly YR20,000 a month in 2015 (roughly US$90 at the time), and that by 2020, the rent for the same flat had increased ten-fold in Yemeni rials.[8]

Rent for commercial real estate has also increased alongside residential housing.[9] One businessman expressed his shock at prices in the city while trying to secure a storefront, and after several attempts, he managed to rent a shop located in the city center for YR300,000 (roughly US$250) per month and a security deposit of 5,000 Saudi riyals (roughly US$1300). The average price of a storefront in the same area was as low as YR25,000 (roughly US$114) in 2015.[10]

Experts also noted the difficulty of purchasing land or housing, explaining that the fact that most land is owned by local tribes limits sales.[11] To make matters worse, nine out of ten IDP settlements are on privately owned land, and over 85 percent of migrants are unable to pay rent on a regular basis. This has created an unstable rental market and increased tensions between migrants and the host community.[12]

Several local and foreign initiatives have attempted to both control price hikes and provide new housing alternatives, with varying levels of success. In 2018, the Industry and Trade Office of Marib capped residential rent prices at 25 percent of 2014 costs, and commercial rent prices at 50 percent. Unfortunately, this failed to prevent rent hikes because it equalized rent costs unilaterally rather than taking into consideration the locations and characteristics of each residential and commercial zone that naturally make certain areas more price-competitive.[13] Meanwhile, in an attempt to help IDPs secure housing, a Kuwaiti-supported project, “Ataa al-Kuwait Residential City,” was inaugurated in December 2022 to build 100 housing units for displaced families and people with special needs in Al-Jufaina camp.[14]Such projects could help to lessen demand for housing and stabilize the real estate market in the governorate.

2. Commercial development and trade

Experts felt that another aspect of life in Marib significantly affected by migration was commercial development and trade. Unlike other trends identified, this was arguably seen as the most beneficial consequence of migration.

In general, experts expressed the belief that the increased population brought by migration has led many goods and services which were not previously accessible to now be readily available to consumers. In 2018, local authorities inaugurated the YR$300 million Saba Mall,[15] followed by the similarly-priced Bawadi Mall which opened in February 2023.[16] The city has also developed hundreds of new restaurants and food chains, transforming a once small, quiet town into a major commercial hub.[17]

Marib city has additionally seen the opening of 900 commercial and industrial projects, including eight commercial banks, multiple money exchange companies, and eateries, creating employment opportunities and enhancing economic movement. These initiatives have benefited entrepreneurs and investors throughout the city.[18]

3. Education

In terms of strains on public services, experts identified the education sector as a third socioeconomic area affected by internal displacement in Marib city. According to a local researcher and development expert, class sizes have grown considerably since the onset of the conflict, with some schools reaching more than 100 students per class.[19]This has created an education crisis that is affecting not only displaced children but also Marib city residents, who now compete for limited seats and resources. A recent UN study using two schools in Marib city as a case study found that host community students made up less than 25 percent of the student population.[20]

Deteriorating infrastructure, limited supplies, and a waning number of qualified teachers plague Marib schools. As of 2021, a little over half of students attended school on a full-time basis, with 35 percent of parents saying that they did not send their children to school because of overcrowding.[21] And according to the IOM, as educational opportunities continue to become scarcer, the competition over limited seats in the classrooms increasingly exacerbates tensions between the host and displaced communities.[22]

Nonetheless, the striking need for new educational avenues has created a vast pool of initiatives to support the education sector in Marib. For example, UN Habitat’s Marib Urban Profile found that Marib city has witnessed relatively high growth rates of both public and private schools during the conflict.[23] Data sourced from the Yemeni Ministry of Education shows that the number of public schools increased from 18 institutions in 2014 to 41 in 2022, while private schools rose nearly tenfold from 2 private centers in 2014 to 19 in 2022. Meanwhile, two education projects sponsored by the Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program for Yemen (SDRPY) were launched in June 2022 in Marib to construct 16 study halls at the University of Saba Region and a Talented Complex Project, which provides 12 classrooms and facilities for gifted students.[24] In a nod to ensuring locals benefit from the development, the university reserved half of the seats in the College of Medicine for native Marib residents.[25] Arguably, the increased investment in educational institutions in Marib would not have occurred were it not for the massive wave of displacement migration.

4. Health

Experts also indicated Marib city’s health sector as another aspect of society that has been heavily impacted by migration. The influx of displaced persons and proximity to the frontlines has put immense strain on an already weak system. According to the Marib Health Office, there is a shortage of medical staff and doctors, as well as supplies and equipment.[26] The cost of private health care has risen considerably since the start of the conflict and many basic medical services are now unaffordable for many. For instance, the average cost of lab work at a private hospital was US$5.99 in 2021;[27] for perspective, in the same year over 90 percent of the governorate’s displaced population lived on less than US$1.40 per day.[28]

Local and international authorities have responded to this health crisis with impressive alacrity, attempting to bolster and transform what was already a weak local health system. Prior to the conflict, Marib governorate was home to less than 50 health-related services, but between 2018 and August 2020 over 200 new healthcare facilities were opened in the governorate, including eight private hospitals and a network of private clinics.[29] Thus, like in the education sector, the migrant crisis in Marib could have promising long-term effects for Marib city’s host community: long after the migrant crisis concludes, locals will benefit from the installation of new health services across the governorate.

5. Infrastructure

Interviewees agreed that Marib city’s infrastructure – which was already inadequate prior to the conflict – has been another major area affected by the IDP influx. Marib, which was known in ancient times for its hydro-engineering feats, has struggled in modern times with providing clean and effective water and sanitation services. This is compounded by weak road services and a lack of public spaces,[30] which make the city increasingly difficult to live in as population numbers rise. Interviewees identified sanitation services as the most pressing issue, reporting that the existing sewer systems regularly overflow, resulting in major hygiene and environmental hazards.[31] A UNICEF report recently found that few people in the governorate have access to a functional latrine, with high numbers of people having trouble accessing any sanitation within a 30-day period.[32] Several initiatives have attempted to tackle this problem, like the Al-Sowayda Water Supply Project, which will provide safe access to 15,000 IDPs across four camps.[33] However, sanitation and access to clean water remain a major problem for both Marib city residents and IDPs.

In addition to water-related problems, Marib city also lacks public spaces, apart from a few small gardens in the center of the city. Overcrowding caused by the migration crisis has left residents and IDPs alike with few places to roam outdoors, and children with no place to play.[34] Marib’s local authorities are attempting to remedy this situation and bolster their communal public spaces with the 22,000 square-meter “Green City” park, which is nearing completion and will be able to accommodate over 700 visitors at any given time.[35] This new space is another hope that Marib’s urban landscape can emerge from the conflict, not only intact but in some ways improved.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Paradoxically, the migrant-related strain on Marib city has both burdened and benefited the host community in a variety of ways. While migrants have exacerbated existing problems – like high rent prices, poor infrastructure, and weak social services – they have also drawn local and international authorities’ attention to these issues. As a result, Marib city has been the focus of dozens of development projects, including new businesses, schools, and health centers that likely would not have existed otherwise. This is not to make light of the strain shared by host communities in this crisis; indeed, local residents have arguably struggled as much as many of the migrants flooding into their city. Nonetheless, it should give Maribis hope that, although their city will be irrevocably changed by the migrant crisis, many of the transformations may be to their benefit. As humanitarian and governmental programs continue to address Marib city’s many challenges, they would do well to remember that Marib was a city before it was a displacement hub, and its residents should continue to lead and engage in the process of developing and reconstructing their home. As such, the following recommendations were developed based on discussions with local experts in the governorate.

To the Local Authorities:

- Establish a mechanism, with the help of the Land, Area, and Urban Planning Authority (LAUPA), to assess which areas of Marib governorate are suitable for urban planning and expansion, and then discuss proposals to sell or donate the land with private landowners. This system or body will allow LAUPA to expand its ability to purchase and acquire lands for public use, habitation, and private business ventures.

- Assess previous attempts to control rent and housing prices in consultation with real estate specialists and investors. These experts should focus on negotiating with tribal land owners to facilitate transactions involving tribal lands and ensure equitable distribution for both residents and newly-arriving IDPs. Future construction projects should focus on the aforementioned critical sectors identified by experts in the governorate, such as multi-story affordable housing, schools, and medical treatment centers.

- Allocate a greater ratio of governorate petroleum to improving or sustaining electricity, water, and other public service provision in the governorate. Given that the most pressing infrastructure- and planning-related issues in Marib city are sewage overflows and a lack of public space, local authorities should coordinate with the Traffic Police Department to redistribute and organize the main roads of the city to facilitate public transportation lines and ease traffic, while also assigning spaces for gardens, public parks, and water and sanitation infrastructure. To ensure that the ongoing construction boom is managed safely, a licensing process should be followed to ensure that residential and commercial properties are constructed in an organized manner.

To the Executive Unit for Managing IDP Camps in Marib and the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation:

- Work to create a digital database of needed specialists willing to come to Marib in addition to any technically-experienced migrants arriving in the governorate in collaboration with IOM. This should include a list of specialists, laborers, teachers, and physicians. Include their contact information in order to facilitate contracting and hiring, allowing local stakeholders to both employ IDPs and address hiring gaps in sectors most affected by the crisis.

To International Organizations Active in Marib:

- Coordinate efforts by employing cluster intervention policies via pilot aid projects. Organizations that are already active in the governorate and subject-area experts should specifically be encouraged to pool their efforts and expertise. For instance, after determining schools are needed in a region with a high population density, ACTED (which has a history of constructing IDP shelters in the region) could utilize its infrastructure-related network to build new classrooms or expand existing ones. UNICEF could use its education-specific resources and contacts to furnish and equip them, while Maribi social leaders who know the community well could raise funding and donations to recruit teachers.

- Refocus efforts on IDPs living outside camps, as this constitutes the vast majority of migrants in Marib city. They should include the development of programs that involve both IDP and host community populations, like vocational training and youth programs, with the goal of long-term migrant integration and social cohesion.

- Develop mechanisms that support Marib’s host community in obtaining commensurate employment and economic opportunities. This will ensure equal distribution of labor opportunities and further work to decrease tensions between the local and migrant communities.

This policy brief was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies in partnership with Saferworld, as part of the Alternative Methodologies for the Peace Process in Yemen program. It is funded by the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO).

- Saad Hizam Ali, “Improving Marib Authorities’ Skills, Capacities to Meet IDP Influx,” Sana’a Center For Strategic Studies, January 4, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/11466

- “Marib [AR],” Yemeni National Information Center, 2004, https://yemen-nic.info/contents/Brief/detail.php?ID=7611&print=Y

- “SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT-EXU MARIB 2022,” The Executive Unit for the Management of IDPs Camps – Marib, September 3, 2022, https://www.exu-marib.com/en/19266/

- “Marib Urban Profile,” United Nations Habitat, March 2021, https://unhabitat.org/marib-urban-profile

- Ibid.

- “Return Remains Distant Hope for Displaced in Marib While Needs Continue to Climb,” IOM, November 15, 2022, https://dtm.iom.int/reports/yemen-intention-survey-marib-idp-sites-september-2022

- Author interview with a Marib-based human rights activist and civil society expert, December 14, 2022.

- “Rising rents are compounding Yemenis’ suffering,” Almasdar Online, January 7, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/238

- Ali Naser, “Real estate in Marib-How does the investor obtain a commercial store for rent? [AR],” Al-Mushahid, April 30, 2023, https://almushahid.net/113761/

- “Marib- a renaissance in real estate and investment [AR],” Akhbaralyom, November 24, 2018. https://akhbaralyom.net/nprint.php?lng=arabic&sid=106381

- Author interview with an employee at a Marib-based non-governmental organization, December 6, 2022.

- “Shelter Needs Soar for Newly Displaced in Yemen’s Marib,” UNHCR Geneva, 2021, https://www.unhcr.org/news/briefing-notes/shelter-needs-soar-newly-displaced-yemens-marib

- Saddam Ali Al-Adour, “Public Policy Paper on the Real Estate Crisis in Marib Governorate (Causes, Effects, and Solutions) [AR],” Economic Studies and Media Center, September 8, 2022, http://www.yemenief.org/Version-Details.aspx?is=66

- “It includes 100 housing units… Inauguration of the Ataa al-Kuwait Residential City project for displaced families and people with special needs in Marib [AR],” The Executive Unit for the Management of Displaced Persons Camps – Marib, December 20, 2022, https://www.exu-marib.com/19595/

- “Marib Dep. Governor Inaugurates Shopping Mall,” Marib Governorate Official Website, May 28, 2018, https://marib-gov.com/nprint.php?lng=arabic&sid=565

- Marib Governorate, “Al-Bakri Inaugurates the Bawadi Mall Complex [AR],” Marib Governorate Official Website, February 21, 2023, https://marib-gov.com/news_details.php?sid=4436

- Peter Salisbury, “Behind the Front Lines in Yemen’s Marib,” International Crisis Group, April 17, 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20210131031830/https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/our-journey-peter-salisbury.pdf

- Abdelsalam al-Ghabari, “Marib… A new era of development and economic recovery for the land of Sheba,” Al-Islah News, February 9, 2019, https://alislah-ye.com/news_details.php?sid=2733

- Author interview with a researcher and development expert based in Marib, December 18, 2022.

- “Yemen Education Cluster – Need Assessment,” Humanitarian Response Education Cluster, United Nations Children’s Fund, October 2021, p. 5, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/education-need-assessment-report-marib-govenorate-october-2021

- Ibid.

- “Al Jeel School Restores Hopes for Thousands of Children in Ma’rib,” IOM Yemen, 2022, https://yemen.iom.int/stories/al-jeel-school-restores-hopes-thousands-children-marib

- “Marib Urban Profile,” United Nations Habitat, March 2021, https://unhabitat.org/marib-urban-profile

- “SDRPY Inaugurates Educational Projects in Marib, Yemen,” Saudi Press Agency, June 16, 2022, https://www.spa.gov.sa/2363092

- “The Opening of the College of Medicine at the University of Sheba Region. [AR]” Al-Sahwa Net, August 25, 2020, https://alsahwa-yemen.net/p-41558

- Deputy Director of the Health Office-Marib Dr. Ahmed al-Abadi, personal interview with the author, November 27, 2022.

- “Marib Urban Profile,” United Nations Habitat, March 2021, https://unhabitat.org/marib-urban-profile

- “Civilians at Risk from Escalating Fighting in Yemen’s Marib.” UNHCR, April 16, 2021, https://www.unhcr.org/news/briefing-notes/civilians-risk-escalating-fighting-yemens-marib

- “Marib Urban Profile,” United Nations Habitat, March 2021, https://unhabitat.org/marib-urban-profile

- Interview with Marib-based civil society activist, December 21, 2022.

- Interview with a human rights activist and media expert in Marib, December 20, 2022.

- “Yemen WASH Needs Tracking System,” ReliefWeb, UNICEF, November 30 2022, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-wash-needs-tracking-system-wants-common-ki-marib-district-marib-governorate-october-2022

- “New Water Distribution Network in Ma’rib Improves Access to Safe Water.” IOM Yemen, January 2023, https://yemen.iom.int/news/new-water-distribution-network-marib-improves-access-safe-water-15000-people

- Hisham al-Shubaily, “Marib… Yemen’s millionth city without a breather for the population [AR],” Independent Arabia, May 12, 2022, https://www.independentarabia.com/node/330576

- “Al-Bakri Inspects Level of Achievement in Green City Park in Marib,” Marib Government Official Website, November 6, 2022, https://marib-gov.com/news_details.php?sid=4234