The Sana’a Center Editorial

Humanitarian Agencies as Prisoners of War

The international relief agencies themselves have become prisoners to the war in Yemen, with their efforts having been mutated from helping to address the country’s suffering into prolonging it. The principal belligerents on one side – Saudi Arabia and until recently the United Arab Emirates, heavily backed by the United States and the United Kingdom – are by far also the largest contributors to the humanitarian relief effort. This allows them to say they are saving Yemeni lives on the one hand while taking them with the other, to say they are feeding Yemen while destroying the economy and infrastructure by which the country might feed itself. Were Yemen to fall into widespread famine, the war would become untenable among the ‘international community’, and thus providing relief funds is a self-serving for these belligerents, allowing them to continue prosecuting the conflict in search of their desired ends.

Given that the majority of Yemen’s population lives in the north most of this aid has gone to areas controlled by the other side. The armed Houthi movement has so thoroughly corralled United Nations agencies and aid organizations that the relief effort, worth almost US$4 billion in 2019 alone, now forms a critical source of rent and influence for the group’s own war effort. This situation came about as a result of the UN and aid organizations progressively and profoundly surrendering their humanitarian principles to try and secure access to needy populations. In doing so, however, these humanitarian actors have reluctantly been providing hefty subsidies for Houthi operations – which include weaponizing starvation, recruiting child soldiers, planting millions of landmines in civilian areas, sexual violence and mass campaigns of arrest and torture.

Humanitarian workers, speaking to the Sana’a Center, have described how, once international aid enters northern areas, the Houthi authorities essentially dictate to UN agencies and international non-governmental organizations the terms of how it is stored and transported, where and when it is distributed, and to whom. Houthi forces have used their control over access to aid, or the threat of its denial, as a means to recruit soldiers from hungry communities in Yemen, to reward support or punish dissent in northern areas, and for cash income through selling the aid supplies on the market. At times corruption has also taken hold within the aid effort itself, with The Associated Press last year revealing a scheme by a small group of foreign staff to embezzle millions of dollars from the World Health Organization. Meanwhile, UN and INGO attempts to verify aid recipients, monitor distribution and even collect basic data for population needs assessments are made nearly impossible due to Houthi-imposed bureaucratic delays, access restrictions and permit denials.

While the UN regularly publishes numbers regarding how many millions of people in Yemen are facing imminent famine, food insecure or otherwise in humanitarian need, it has been extremely difficult to verify these statistics with on-the-ground surveys. Indeed, evidence suggests that in some locations needs have been inflated to garner more resources, while at the same time other areas remain overlooked and underserved. Put another way, no definitive data actually exists to confirm the often-stated claim that Yemen is “the world’s largest humanitarian crisis”, though it may be the world’s worst humanitarian response.

There is without question immense humanitarian need in Yemen; however, many UN and INGO staff on the ground – the people in the best position to know – have lost confidence that the relief effort, as it is currently being conducted, is helping the situation. At best, it is offering a few Yemenis the brief reprieve humanitarian aid is meant to provide, but in exchange for indefinite suffering through a drawn-out conflict.

Recent international threats to withdraw aid funds from northern areas if the Houthi authorities do not loosen their throttle hold over the relief effort have shown a degree of success – such as getting the Houthis to agree to back down on a proposed 2 percent tax on all humanitarian operations, though indications are that the Houthis are pursuing other avenues to recoup these funds from relief agencies. And even here the response of the humanitarian actors is ethically fraught. It is because the United Nations had been so fearful of losing access that the humanitarian effort became so compromised, and the UN only began to meaningfully confront the Houthis last year after it was forced to by media reports exposing the rampant and systematic theft of food aid. Talks between the World Food Programme, which receives the lion’s share of all aid funding, and the Houthi authorities regarding the implementation of biometric registration for aid recipients dragged on for much of 2019 with no tangible results. Meanwhile, Houthi restrictions on the humanitarian effort continued to escalate. After behind-the-scenes pressure from the UN and INGOs to convince the Houthis to change course yielded no results, donors – among the more vocal being the United States Agency for International Development – have stepped in and are publicly threatening to withdraw funding for UN and INGO operations in Yemen to force concessions from the Houthis.

While the heads of UN agencies were confronted with crushing responsibility and immensely difficult choices during the Yemen conflict, they are also meant to be the standard bearers of humanitarian principles in the world. In this, the UN abdicated its responsibility in Yemen. Into this vacuum, the donors – the largest of whom are active belligerents on one side of this conflict – are now stepping in. This sets a new, dangerous precedent and further erodes the UN’s ability to direct a needs-based relief effort that is autonomous from the objectives – political, economic, military or otherwise – of actors in this war.

Contents

-

Frontlines Erupt, Airstrikes and Cross-Border Attacks Resume

- Fierce Fighting Between Houthi, Govt Forces in Various Governorates

- Deadly Uptick in Air and Missile Strikes During Northern Fighting

- Houthis Shoot Down Saudi Warplane in Al-Jawf

- Yemeni Defense Minister’s Convoy Strikes Landmine in Marib, 6 Killed

- UN Warns Escalation Could Wipe Out All Recent Progress

- Military and Security Developments

- Political Developments

-

Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments

- Saudi Announces Trials for Air Raids on Hospital, Wedding, School Bus

- First ‘Mercy Flights’ Carrying Critically Ill Depart Sana’a Airport

- Civilian Casualties Climbing, More than 35,000 newly displaced, Hospitals Hit

- Egyptian Fishermen Killed by Sea Mine, 32 Others Freed From Houthi Jails

- Amid Coronavirus Outbreak, Yemeni Students Still Stuck in Wuhan

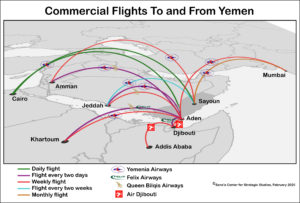

- Graphic: Commercial Flights to and from Yemen

- At the United Nations

- In the United States

-

In the Region

- Where is Saudi Arabia Headed in Yemen? – Commentary by Thomas Juneau

- US Kills Quds Force Leader, Targets Iranian Commander in Yemen

- Oman’s Sultan Qaboos Dies After 49 Years of Rule

- UAE Withdraws More Troops, Shifts to Background Role via Proxies

- Official: Fewer Than 1,000 Sudanese Troops Left in Yemen

- In Europe

The War Over Aid

Houthi Aid Interference Prompts Threats to Cut Funding

Mounting disputes between aid agencies and Houthi authorities in Sana’a that have severely impeded the relief effort and a donor rebellion could result in deep cuts to vital humanitarian aid. Large donors along with UN agencies and other international NGOs who met February 13 in Brussels said the situation “has reached a breaking point,” as an investigation by The Associated Press revealed details of the extent of Houthi demands and past UN acquiescence to them.[1]

An aid worker who manages programs in Yemen for an international non-governmental organization (INGO) told the Sana’a Center that UN agencies had ceded too much control to Houthi authorities throughout the conflict; UN food aid delivered to Hudaydah port had been transported by Houthi affiliates and stored in a warehouse belonging to the Houthi-run Education Ministry.[2] Houthi authorities also were granted excessive influence over beneficiary lists and distribution, while the UN lacked staff on the ground to monitor distribution or verify needs, the aid worker said on condition of anonymity due to fear of repercussions.

Houthi restrictions on visas, travel and supplies create an extremely difficult operating environment, the aid worker said. Securing visas for international humanitarian staff requires permission from the Houthi-run Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and International Cooperation (SCMCHA), health ministry and national security; these bodies often are not aligned, and if one rejects the application, the process must begin again. The process takes up to six months, sometimes culminating with a refusal for absurd reasons, while Houthi authorities frequently lose papers, according to the aid worker. Meanwhile, to travel within Yemen, staff must request a travel permit from Houthi authorities a week in advance.

The internationally recognized government requires international humanitarian staff entering any part of Yemen to obtain a visa from their authorities, a process that usually takes 24 hours, but the government refuses visas for Lebanese, Iraqis, Iranians and Syrians. Meanwhile, Houthi authorities refuse visas to anyone who has been to Gaza. Combined, these restrictions limit the pool of staff that the sector can recruit from, the aid worker explained.

Obtaining permission from Houthi authorities to bring in humanitarian supplies can take up to six months, sometimes past the shelf-life of the food or medicine being imported. Houthi authorities insist INGOs use Houthi trucks to transport supplies, creating another stream of income for the Houthis through transport fees. Further, Houthi authorities raised social security deductions on humanitarian staff’s salaries from 15 to 18 percent; organizations that do not pay risk refusals for visas and travel permits, the aid worker said.

To attend training abroad, humanitarian staff must obtain authorization from the Houthis; this requires presenting the training curriculum and attending an interview with Houthi officials who decide whether or not to allow the staff member to attend. A recent restriction imposed by SCMCHA forbids INGO staff from meeting with any Houthi authorities or officials except SCMCHA, according to the aid worker.

UN and INGO officials had said little publicly about details of their dispute and past cooperation and financial arrangements with the Houthi authorities. However, Mark Lowcock, the UN under-secretary-general for humanitarian affairs, briefed the UN Security Council in open session on the issue February 18, the day before The Associated Press published an investigation into the situation.[3] The AP investigation, based on dozens of documents and interviews with anonymous aid officials who said they feared reprisals for speaking out, found that:

- Houthi authorities delayed permission to distribute food for 160,000 people in Aslam district, Hajjah governorate, granting approval only in November after the food had spoiled;

- about US$133 million of the $370 million in UN-provided direct cash transfers to government institutions, mostly controlled by the Houthis, went unaudited — money intended to support administrative costs for local institutions, including SCMCHA, and salaries for doctors, teachers and others civil servants;

- three UN agencies were making salary payments for a time to the president of SCMCHA, his deputy and general managers totaling $10,000 a month for each;

- since November, SCMCHA has imposed more than 200 new directives and demands, including requiring the disclosure of aid recipients’ identities, allowing Houthi authorities to take over the budgets of monitoring programs, involving Houthi authorities in need assessments as well as in assigning suppliers for UN contracts and selecting local partners for UN programs, screening UN hires in Yemen and requiring Yemeni employees to attain Houthi permission for UN training courses abroad and then report back on the workshops’ content; and

- Houthi authorities were trying to force the UN to work with Bonyan, a local aid organization with many Houthi affiliates.

UN agencies have refused to sign agreements to accept the new directives. In his UN Security Council briefing, Lowcock cited issues with both sides in the conflict but described “much more serious problems” in Houthi-controlled areas.[4] He confirmed the 200-plus new directives and said that by the end of 2019, incidents of Houthi disruption of assistance were six times greater than at the start of the year. Lowcock characterized half of the incidents as constraints on movement of staff or supplies and said about a quarter involved trying to influence aid decisions or otherwise interfere in programs. He confirmed Houthi authorities had demanded a 2 percent tax on all aid funding — and noted they had rescinded the demand in February — and that NGOs were asked to sign agreements that were inconsistent with humanitarian principles (see “Houthis Replace Aid Coordination Body; UN Cites ‘Alarming’ Mistreatment,” The Yemen Review, November 2019).[5]

In remarks just ahead of the Brussels meeting, the head of SCMCHA, Abdel Mohsen Tawoos, described threats to cut aid as “extortion” that would not work.[6] As the pressure increased, however, the Houthis made some other concessions. Lowcock told the Security Council they recently had returned food taken from a warehouse in Hajjah and had sent a written agreement to begin biometric registration for food aid recipients, though they have not yet implemented that long-sought monitoring measure.

Houthi authorities failed to approve 40 percent of NGO projects in 2019, which Lowcock compared to the 30 percent of projects stopped because the internationally recognized Yemeni government failed to approve them. He also spelled out more clearly than in the past some of the issues the UN was having in government-run areas, including proposed regulations that would make it more difficult for humanitarian agencies to move around the country to meet urgent needs. In the past week, he said in his February 18 briefing, the government had returned eight trucks transporting medical supplies that government forces had detained in Marib since January 30, but with 70 percent of the supplies missing.[7]

USAID announced February 24 that it would suspend aid to Houthi-controlled areas from late March unless the Houthis removed obstacles to aid operations.[8] The United States provided around $700 million to Yemen in 2019. Earlier, the US and UK governments had warned Lowcock, they would cut their donations to relief operations unless less funding was provided to Houthi-controlled institutions, according to The New Humanitarian, which reported it had seen a draft letter to Lowcock dated February 5.[9] After the Brussels meeting, the donors, UN agencies and other international aid organizations threatened to scale back or suspend operations “if and where delivery of humanitarian aid in accordance with the humanitarian principles is impossible.”[10]

Looming Monetary Threats Risk Rapid Inflation as International Aid is Reduced

The potential for large cuts to relief funding will put downward pressure on the value of the domestic currency, the Yemeni rial (YR), given that foreign aid today constitutes one of the country’s largest sources of foreign currency. These cuts also come to the fore, however, as two other significant threats to the value of the rial have emerged: the US$2 billion deposit Riyadh made in 2018 to the government-controlled central bank in Aden – which the bank has used to subsidize imports of rice, wheat, sugar, milk and cooking oil – is running out;[11] while a Houthi ban on banknotes issued by the Aden central bank[12] has also introduced increased volatility into the currency market. Given that Yemen overwhelmingly depends on imports to feed itself, the value of the Yemeni rial has a direct and immediate impact upon general purchasing power and food security in the country. The current confluence of factors threatens to bring about a situation where foreign aid drops off just as Yemenis are less able to purchase food and other supplies on the commercial market.

On January 22, the Central Bank of Yemen in Aden announced the distribution of US$227 million from the Saudi deposit to finance the import of essential commodities. With the latest allocation and disbursement of funds, at the end of February there remained US$390 million to underwrite letters of credits (LCs) for essential commodity imports. According to a senior banking official in Aden, the Aden central bank has already initiated procedures to disburse the remaining funds, with the Saudi deposit expected to be depleted by mid-2020 at the latest.

The Saudi deposit has played a critical role in helping to stabilize the Yemeni rial, and until now there has been no clear indication from Saudi Arabia that it will provide additional funding to fill the void that will be left. The internationally recognized Yemeni government is not yet generating enough foreign currency on its own to underwrite the LCs system it rolled out in July 2018 and then refined in November 2018.

Meanwhile, throughout January and February the divergence between the Yemeni rial-US dollar exchange rate in Sana’a and Aden continued to increase. On February 28, the exchange rate in Sana’a was YR 597-600 per US dollar, compared with 657-660 Yemeni rials per US dollar in Aden, a roughly 10 percent difference.[13] This can largely be explained by the continued enforcement of the ban on newly printed Yemeni rial banknotes — those issued by the Aden central bank after 2016 — in Houthi-controlled areas, and specifically the increased movement of new rial liquidity away from Sana’a to Aden. There are now diverging exchange rates in Yemen between northern and southern areas, between new and old banknotes, and between cash, check and a new Houthi-introduced e-currency. This increasingly fragmented foreign exchange system for the Yemeni rial will increase its vulnerability to pressure shocks and resultant price volatility. For more details on the implications of the ban that the Central Bank of Yemen in Sana’a introduced on December 18 and continues to enforce, see: “Yemen Economic Bulletin: The War for Monetary Control Enters a Dangerous New Phase.”[14]

Developments in Yemen

Frontlines Erupt, Airstrikes and Cross-Border Attacks Resume

Fierce Fighting Between Houthi, Govt Forces in Various Governorates

The first two months of 2020 saw renewed violence between the armed Houthi movement and forces aligned with the Yemeni government across multiple fronts, in what observers described as the fiercest fighting in some areas in years. Officials told The Associated Press in late January that both sides were sustaining heavy losses in Al-Jawf and Marib governorates, and in Nehm district, a mountainous region a short drive northeast of the capital Sana’a.[15] Renewed clashes also broke out further south in Taiz and Al-Bayda governorates. Toward the end of January, Houthi forces captured the Sana’a-Marib governorate border checkpoint, a highly strategic intersection where the road north to Al-Jawf and east to Marib meets.[16]

Clashes in Al-Jawf, Marib and Sana’a continued through the month of February, while fighting also erupted along frontlines in Al-Dhalea and Hudaydah governorates. The Houthi movement claimed on February 20 to have halted a government offensive in Durayhimi, a town just south of Hudaydah, killing 18 troops. The Saudi-led coalition also fired several missiles and conducted numerous airstrikes against the Houthi-held town.[17] Meanwhile, the AP reported in late February that 50 fighters on both sides had been killed in fighting in Al-Jawf over four days.[18]

Deadly Uptick in Air and Missile Strikes During Northern Fighting

Missile attacks and airstrikes carried out by the Houthi movement and the Saudi-led coalition, respectively, increased in concert with the escalation in fighting on the ground. This represented a dramatic reversal from the last three months of 2019 when the Houthi movement and Saudi Arabia agreed to a partial cease-fire, with the former halting cross-border missile attacks and the latter ceasing airstrikes in multiple governorates, including around the capital Sana’a.[19] Both of these redlines were shattered by the end of January. Many of these attacks resulted in civilian casualties, with UN humanitarian chief Mark Lowcock saying that 160 civilians had been killed or wounded in January alone[20] (See ‘Civilian Casualties Climbing, More Than 35,000 Newly Displaced, Hospitals Hit‘)

In one of the deadliest attacks in the nearly five-year history of the Yemen war, a Houthi missile and drone attack against a government military camp in Marib on January 18 killed at least 111 people.[21] A missile hit a mosque in the compound during evening prayers; the timing of the attack contributed to the high death toll. In the days following the attack, the Saudi-led coalition military increased airstrikes in areas that were experiencing heavy fighting on the ground. Airstrikes on the Nehm front killed at least 35 people while the coalition also carried out air raids against Houthi forces in Marib.[22]

On January 30, the Houthi movement announced that it had launched rocket and drone strikes at targets inside Saudi Arabia, the first publicly claimed cross-border attacks by the group since the cease-fire offer in September. Yahya Sarea, military spokesperson for the group, said Houthi forces had carried out 15 operations targeting Aramco facilities in Jizan, Abha and Jizan airports and Khamis Mushait military base in addition to targets along the Saudi-Yemen border. The Houthi spokesperson characterized the attacks as retaliation for the recent uptick in coalition airstrikes.[23]

Both sides continued with their air war throughout the month of February. According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, Saudi warplanes carried out nearly 50 airstrikes in the first week of the month.[24] On February 21, Saudi Arabia claimed to have intercepted several ballistic missiles launched from Sana’a toward several Saudi cities.[25]

Houthis Shoot Down Saudi Warplane in Al-Jawf

Amid fighting in Al-Jawf governorate, the Houthi movement shot down a Saudi Tornado fighter jet on February 14. Coalition spokesperson Turki al-Maliki said a coalition warplane had crashed while “providing close air support to units of the Yemeni National Army” and that two personnel onboard had ejected before the plane crashed, adding that Saudi Arabia held the Houthi movement responsible for their safety.[26] The fate of the pilots has not been confirmed. The Houthi movement released purported footage of the jet being targeted with an advanced surface-to-air missile.[27] Saudi Arabia carried out retaliatory airstrikes in the area the following day, which killed 31 civilians, according to the UN.[28]

Yemeni Defense Minister’s Convoy Strikes Landmine in Marib, 6 Killed

An explosion killed six bodyguards of Yemeni government Defense Minister Mohammed al-Maqdishi and wounded eight others after the minister’s convoy struck a landmine in Marib on February 19. Al-Maqdishi, who had been surveying frontlines in Serwah in the flashpoint governorate, emerged unscathed.[29]

UN Warns Escalation Could Wipe Out All Recent Progress

Only days after informing the UN Security Council (UNSC) on January 16 that the month thus far had been among the quietest in the conflict,[30] a dramatic uptick in violence on multiple fronts prompted UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths to warn that all progress made in recent months could unravel.[31]

The United Kingdom, penholder of the Yemen file at the UNSC, convened emergency consultations on January 28 in response to the escalating fighting, during which Griffiths provided a closed-door video briefing.[32] UNSC President Dang Dinh Quy of Vietnam noted in a January 30 press statement the council’s “disappointment” with the return to violence as well as the need to end hostilities and ensure accountability for violations of any international humanitarian law.[33] Griffiths also appealed for deescalation on Twitter, saying Yemenis “deserve better than a life of perpetual war.”[34]

Military and Security Developments

Saudi Troops and Local Tribes Clash in Al-Mahra, Governor Dismissed

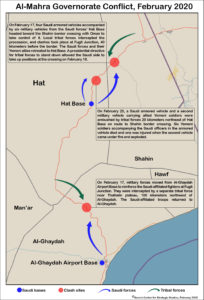

An attempt on February 17 to stop the deployment of Saudi troops in Al-Mahra near the border with Oman devolved into clashes, in the latest escalation in a conflict pitting local tribes supported by Oman against an increasing Saudi military presence in Yemen’s easternmost governorate. Local tribal forces confronted a convoy of four Saudi armored vehicles accompanied by six other military vehicles en route to take control of the Shahin border crossing, according to local sources on the ground. Following clashes at Fugit Junction, 40 kilometers before the border, the Saudi forces and their Yemeni allies retreated to Hat Base. A presidential directive for tribal forces to stand down allowed the Saudi side to take up positions at the crossing on February 18. Shahin, which hosts one of the governorate’s major border crossings with Oman, was also the site of clashes in March 2019 when local tribesmen blocked the passage of Saudi shipping containers entering the country.[35]

In the wake of the incident, President Hadi dismissed Al-Mahra Governor Rajeh Bakrit on February 22. Bakrit, who was viewed as the Saudi’s main man in the governorate, had been called to Riyadh for consultations in the wake of the clashes.[36] His replacement, Mohammed Ali Yasser, is a current MP and former governor. The deputy head of the sit-in committee opposed to the Saudi presence in Al-Mahra characterized the removal of the “gangster” Bakrit, who has been accused of corruption, and appointment of Ali Yasser as a step in the right direction.[37]

While the governorate has not been directly affected by the conflict between the government and the armed Houthi movement, Riyadh began establishing a military presence there in late 2017, under the pretext of combating smuggling. By the end of 2019, Saudi troops had asserted control over various ports and border crossings and established almost two dozen military bases in Al-Mahra, suggesting broader ambitions in the governorate.

Meanwhile, Oman, which historically has close ties to the Yemeni governorate on its western border, has seen the Saudi military presence as an infringement in its backyard and supported the protest movement against the presence of foreign troops. According to Sana’a Center research, during 2018 and 2019 Muscat increasingly provided financial support to tribes opposing the Saudi military presence (for more information, see ‘Saudi-Omani Rivalry Escalates in Al-Mahra’ in The Yemen Annual Review 2019).[38].

The End of AQAP as a Global Threat

Commentary by Gregory D. Johnsen

More than 15 years ago, in November 2003, the United States and the then Yemeni government of President Ali Abdullah Saleh defeated the first iteration of Al-Qaeda in Yemen. That victory did not last long. Less than two-and-a-half years later, in February 2006, 23 Al-Qaeda suspects tunneled out of a prison in Sana’a and into a neighboring mosque, where they walked out the front door to freedom.

Among the escapees that early morning were Nasir al-Wihayshi and Qasim al-Raymi. Both men had spent time in Afghanistan prior to the September 11, 2001, attacks on New York and Washington. Al-Wihayshi had been Osama bin Laden’s secretary and aide-de-camp, while Al-Raymi had been an instructor at one of Al-Qaeda’s training camps. According to one source, Al-Raymi would later marry one of Al-Wihayshi’s daughters.[39]

Over the next three years, Al-Wihayshi and Al-Raymi patiently rebuilt Al-Qaeda’s infrastructure in Yemen, resurrecting it from the ashes of its earlier defeat. Under their leadership, Al-Qaeda in Yemen transitioned from a small group capable of one-off attacks to an innovative organization able to threaten the United States. In January 2009, as part of this rebuilding process, Al-Wihayshi and Al-Raymi joined with two former Saudi detainees at Guantanamo Bay, Said al-Shihri and Mohammed al-Awfi, to form Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, or AQAP.

Within months the new organization had wounded Saudi Arabia’s then-Deputy Minister of Interior, Mohammed bin Nayif, in an assassination attempt and managed to smuggle a bomb on board a Detroit-bound airliner on Christmas Day, 2009. The rise of Anwar al-Awlaki as a recruiter and jihadi orator and the bomb-making skills of Ibrahim al-Asiri led US intelligence agencies and analysts throughout the Obama years to frequently describe the group as Al-Qaeda’s “most dangerous affiliate.”[40] This continued to be the case even after the deaths of Al-Awlaki in 2011, Al-Shihri in 2013, Al-Wihayshi in 2015 and Al-Asiri in 2017. But the truth is: In recent years, AQAP has atrophied. The group no longer presents the same terrorist threat that it once did. It exists, yes, but only as a shadow of its former self. Indeed, 2020 could be the year the US decisively defeats AQAP and effectively eliminates the group as an international terrorist threat. (AQAP will likely continue to present a domestic threat within Yemen for some time to come.)

In late January 2020, the US carried out three drone strikes in Yemen, killing Al-Raymi, the head of AQAP.[41] The first two strikes, on January 25 and January 27, took place in Marib. But, according to Yemeni media, it was the third strike on January 29, which took place in Al-Bayda, that killed Al-Raymi and another member of AQAP, Abu al-Baraa al-Ibbia, as they were driving.[42]

The United States, of course, has been down this road before, believing it has killed Al-Raymi only to have it later revealed that he survived. Al-Raymi was also the target of the January 2017 SEAL raid in Yemen, which led to the death of Yemeni civilians including at least six women and 10 children under the age of 13, as well as an American soldier.[43] US suspicions turned out to be correct this time, however, with AQAP confirming Al-Raymi’s death on February 23.

Along with publicizing the killing of their former leader, AQAP also announced that Khalid Omar Batarfi, a Saudi national of Yemeni origin, would replace Al-Raymi as the group’s commander. According to a recent UN report, Batarfi has already been in charge of AQAP’s external operations since 2017.[44] Like Al-Wihayshi and Al-Raymi, Batarfi has links to the pre-9/11 Al-Qaeda. He trained at Al-Farouq camp in Afghanistan in 1999, and was in the country on September 11, 2001. Batarfi has done two stints in Yemeni prisons, from 2002 to 2004, when he was released by then-president Ali Abdullah Saleh’s government, and again from 2011 until April 2015, when AQAP took control of the port city of Mukalla in Hadramawt governorate and released Batarfi and more than 200 other prisoners from the local Central Security prison.

Batarfi will face an uphill task in attempting to resurrect a dying organization. AQAP is weaker and more disorganized than it has ever been. Al-Raymi, who was an effective operations commander, struggled as an overall commander and leader, famously giving an exceedingly dull 40-part lecture on a medieval treatise. The combination of Al-Raymi’s poor leadership skills, a surge in US drone strikes in 2017, on-the-ground operations by UAE-backed forces in Yemen and a jihadi rival in the Islamic State (IS) have all combined to erode AQAP’s strength in recent years.

Indeed, up until February 2020, the last international attack that AQAP claimed (at least some) responsibility for was the January 2015 attack on the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris. On February 2, 2020, AQAP released an 18-minute message, featuring audio from Al-Raymi (likely recorded between September and December 2019), taking credit for the December 6, 2019 shooting by Mohammed al-Shamrani at the Naval Air Station in Pensacola, Florida.[45] The attack killed three people and wounded several others. In the video, AQAP shows a two-page will from Al-Shamrani to his family, but otherwise provides no evidence to corroborate the impression that Al-Shamrani was acting on AQAP’s orders. Instead, the video and audio look as though Al-Raymi is trying to pass off an inspired attack as a directed one. This is the messaging of a weak organization attempting to look relevant after years of international inactivity.

Much like in 2003, AQAP is once again teetering and on the ropes. It has few qualified leaders and is no longer attracting many international recruits. The death of Al-Raymi is a blow; a few more losses like him and AQAP will be unlikely to recover, its international terrorist wing shattered.

Dr. Gregory D. Johnsen is a non-resident fellow at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies where he focuses on Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State and armed groups in Yemen. Prior to joining the Sana’a Center, Dr. Johnsen served on the Panel of Experts on Yemen for the United Nations Security Council. He is the author of ‘The Last Refuge: Yemen, al-Qaeda, and America’s War in Arabia’.

Not So Fast: Founder’s Death a Blow to AQAP, but not Fatal

Commentary by Hussam Radman

When Qasim al-Raymi mourned his predecessor and lifelong friend, he said the 2015 US drone strike that killed Nasir al-Wuhayshi had fulfilled the Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) leader’s dream of martyrdom. Following Al-Raymi’s own death in a US military operation this January in Yemen, his assassination has stirred debate about whether AQAP can survive without this charismatic and capable leader, who had been the last surviving member of the group’s founders. Al-Wuhayshi’s view on such matters was clear in remarks he made about five years before his death: “America is wrong if it thinks it has won by killing this (or that) commander. Jihad continues until Doomsday!”[46]

Doomsday may be optimistic, but a painful blow is not necessarily a death blow. AQAP has been regressing since 2016, and this may worsen with the death of Al-Raymi. His newly appointed successor, Khalid Batarfi, also known as Abu al-Meqdad al-Kindi, is first-generation Al-Qaeda, having fought alongside Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan. He is, however, Saudi, and Al-Wuhayshi and Al-Raymi had succeeded in Yemenizing AQAP, allowing it to create social incubators and safe havens across the country. A non-Yemeni could disturb the group’s ties with the tribal community in which it moves. Still, Al-Raymi’s management of a pivotal transition within AQAP through a series of decisive, strategic and operational changes has maintained the organization’s unity and provided resilience. Ultimately, Al-Raymi prevented a split within AQAP (as happened to Al-Qaeda in Syria) or its disintegration (as happened to the Islamic State group), and the group can draw on the strategy he left behind to survive.

It’s only with Al-Raymi’s death that Nasser al-Wuhayshi’s era ended. Both men played vital roles in the group’s ideological establishment. They studied together at the Faculty of Sharia and Law at the University of Sana’a, and both joined the jihadists in Afghanistan in the early 1990s. At the time, Al-Wuhayshi was Osama bin Laden’s secretary while Al-Raymi recruited and trained fighters at the Al-Ansar camp in Pakistan in support of the Taliban.[47] After the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, Al-Raymi and Al-Wuhayshi both ended up back in Yemen — reunited in a Sana’a prison. They participated in a dramatic prison escape in 2006[48] and, in 2007, set up what would become known as Al-Qaeda in the Southern Arabian Peninsula with Al-Raymi as spokesperson and military commander.[49] Upon integrating with Al-Qaeda’s branch in Saudi Arabia, AQAP was born. Al-Raymi successfully recruited Yemenis and Arabs as was evident in 2011, when AQAP launched widespread operations against Yemeni army posts.[50]

When Al-Ramyi succeeded Al-Wuhayshi as the group’s leader in 2015, AQAP was facing four existential threats: Severe divisions in the jihadi community, resulting in a bloody conflict with the Yemeni branch of the Islamic State group; infiltration by Saudi intelligence combined with US military operations; the rise of UAE-backed southern separatists as political players in the south and the shift of internationally recognized Yemeni state institutions to Aden, ending the vacuum of authority in southern Yemen; and Houthi expansion of control in critical areas of central Yemen.[51]

Al-Raymi responded to these challenges by strategically repositioning within Yemen. After controlling Mukalla in Hadramawt governorate – Yemen’s fifth-largest city – for a year, but facing a UAE-led campaign to retake the city, AQAP notably withdrew in April 2016. The group also withdrew from other urban areas following the Saudi- and Emirati-led military coalition’s campaign that retook Shabwa, Lahj, Abyan and Aden governorates from Houthi forces. Meanwhile, he restructured the organization, ending security breaches by purging suspected spies. He also rearranged his jihadi priorities, shifting the group’s emphasis from being an Islamic emirate to being a revolutionary organization. (In jihadist terminology, this reflects reversing course from “jihad of empowerment” to a “jihad of defiance.”)[52] Al-Raymi also benefited from the Islamic State’s lack of local understanding and ideological inflexibility, allowing AQAP to dominate the local jihadi scene.

Beyond managing these shifts, AQAP as an organization draws resilience from its ideological coherence. To Al-Qaeda, the blessed time of the caliphate has not yet come and must be prepared for through jihad, armed struggle, and by reforming society through implementing sharia, Islamic law. Therefore, the fall of the emir or emirate does not represent a catastrophe to Al-Qaeda’s ideology because the group’s essence is its “jihadi-revolutionary” project — creating a faithful and just society by ridding it of nonbelievers. This differs from IS, which derives its religious legitimacy and ideological attractiveness from the establishment and expansion of a caliphate and inauguration of a caliph; once that caliph’s authoritarian influence ends, the caliphate ends.

In shifting priorities, Al-Raymi instilled a strategic approach that provides another source of stability. It can be summed up in several points: First, the safety of the organization is more important than gains on the ground, in authority or in finances. Second, strategic concealment within Yemen can shift the nature of internal operations toward defensive purposes, such as defending AQAP positions in Al-Bayda against the Houthis, and must coexist with operational expansion outside this arena. For example, the group can strengthen its cooperation with Al-Qaeda branches in Somalia and Afghanistan during these times or strike against Western targets, even if that means so-called “lone wolf” attacks because the group itself cannot carry out strategically significant attacks. Third, slowing the pace of recruitment, reducing top commanders’ movements and increasing covert work is acceptable to avoid Saudi and American infiltration. However, this may not have been entirely effective; The New York Times reported that the CIA learned of Al-Raymi’s location through an informant in Yemen, allowing the US to track al-Raymi with surveillance drones.[53]

Al-Qaeda’s organizational structure is independent, its connections firmly rooted and it enjoys a degree of institutionalization. So while losing an emir can temporarily disrupt the flow of information and orders and hurt morale, it is unlikely to bring down the system. Furthermore, the unstable security situation in southern governorates since the August 2019 infighting among the anti-Houthi coalition has eased pressure on AQAP. The fallout weakened Security Belt forces in Abyan and resulted in the defeat and dispersal of the Shabwani Elite Forces in Shabwa – the two most significant local parties combating terrorism in each area. These developments created an environment for the return of jihadi organizations, providing them safe havens and allowing more freedom of movement to AQAP leaders and members in Abyan, Al-Bayda, Shabwa and Marib governorates. The extent and nature of the consequences of Al-Raymi’s death on AQAP cannot be predicted, but rapid extinction is not one of them. Batarfi may not enjoy the sort of automatic local protection his Yemeni predecessor did, but Al-Raymi left AQAP positioned to survive as an institution.

Hussam Radman is a journalist and Sana’a Center research fellow who focuses on militant Islamist groups and southern Yemen politics.

Political Developments

Hopes Emerge for Long-Awaited Prisoner Exchange

The Yemeni government and the Houthi movement, following negotiations during the month of February, are expected to carry out the first large-scale prisoner exchange since the beginning of the Yemen war. The breakthrough came following a week of talks in Amman, Jordan, which were co-chaired by the Office of the Special Envoy for Yemen and the International Committee of the Red Cross, and included delegations from both the Yemeni government and Houthi movement, along with representatives from the Saudi-led coalition. In a statement released February 16, the UN special envoy’s office announced that the sides had agreed to a “detailed plan” as part of their commitment to fulfilling the prisoner exchange aspect of the Stockholm Agreement.[54]

A mass prisoner swap between the Yemeni government and the Houthis has been long rumored and a popular demand for both sides. In the nearly five-year history of the conflict, all prisoner exchanges thus far have been brokered via local mediation efforts or as a result of negotiations between the armed Houthi movement and Saudi Arabia.[55] The two sides almost agreed to an “all for all” exchange in June 2018 to coincide with the end of Ramadan, but after those negotiations stalled, the UN incorporated the issue into its deescalation efforts, culminating in a prisoner exchange deal being included in the Stockholm Agreement in December 2018. However, despite a commitment to exchange some 15,000 prisoners, and two rounds of talks held in Amman in January and February 2019, no deal took place as the parties failed to agree on finalized lists. The issue was eventually put on the back burner as the Hudaydah component of the Stockholm Agreement consumed the majority of the UN envoy’s attention.

The upcoming swap is expected to see the sides exchange 700 prisoners each as a first step, according to Yemeni sources in both the government and Houthi delegations that spoke the Sana’a Center. The same sources said that a breakthrough emerged after the sides dropped demands that specific individuals be included as part of the deal, instead agreeing to just release an equivalent amount of prisoners. Still, political intrigue remained surrounding some of the higher-profile Houthi detainees: General Naser Mansour Hadi, brother of Yemeni president Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi; Defense Minister Mahmoud al-Sobaihi; Commander of the 31st Armored Brigade General Faisal Rajab; and senior Islah party official Mohammed Qahtan. During the February negotiations the Houthis offered to free Naser Hadi – likely in an effort to create a fracture between the president and his Islah allies – but the government delegation responded by demanding the release of the other three figures instead. In the end, a deal was struck to include Naser Hadi in the upcoming swap while the Houthis agreed to allow visits to check on the health of the other three prisoners.

A number of Saudi prisoners held by the Houthis are also expected to be released as part of the deal. A source involved in the negotiations told the Sana’a Center that Riyadh is seeking the release of more than 50 Saudis, including 30 who were captured in August 2019 during battles in Kitaf, Sa’ada governorate, which ended in a massive defeat for coalition forces.[56] The Houthis had attempted to bypass the Yemeni government and negotiate directly with the Saudis, but Riyadh refused, despite doing deals with the Houthis in the past and the ongoing backchannel talks with the movement,[57] and insisted that talks must be conducted Yemeni-to-Yemeni.

Riyadh Agreement Hangs by a Thread Amid Rising Tension in Southern Yemen

Implementation of the Riyadh Agreement in 2020 has followed the same pattern as the final months of 2019: one step forward and two steps back. The deal between the Yemeni government and Southern Transitional Council (STC), under the sponsorship of Saudi Arabia, sought to halt months of infighting in southern Yemen by absorbing the STC politically and militarily into the Yemeni government. However, since its signing in November 2019, little progress has been made on the political, military or security fronts. Instead, deadline after deadline has been missed on the composition of a new government, the redeployment of forces in southern Yemen from positions seized during fighting between the sides since August and the formation of a unified military command ultimately answerable to Riyadh. By the end of February, the future of the agreement was in more doubt that ever amid heightened tension between Yemeni government and STC-aligned forces.

The new year began with political wrangling between the sides over the redeployment of forces. On January 1, the STC announced it was suspending participation in joint committees intended to implement aspects of the accord, citing a minor flareup in violence in Shabwa governorate that it blamed on the Islah party.[58] However, this suspension did not hold, and on January 9 the Yemeni government said it had signed a deal with the STC for both sides to withdraw forces from Aden by the end of the month, in fulfillment of the Riyadh Agreement.[59] Saudi Ambassador to Yemen Mohammed al-Jaber announced on Twitter that a “matrix” had been agreed to begin implementing phase II of the agreement, which dictated the appointment of a governor and security chief in Aden, and the return of all forces and equipment in Aden, Abyan and Shabwa to their pre-August 2019 positions.[60] The original deadline for appointing a new Aden governor and security chief and the redeployment of forces in the southern governorates was November 20, 2019. The pullout of all government and STC military forces from Aden to camps outside the governorate, except for the 1st Presidential Protection Brigade, and the transfer of medium and heavy weapons in Aden to camps in the city under Saudi supervision was supposed to occur on December 5, 2019.

The first joint pullout began January 16 in Zinjibar, capital of Abyan governorate.[61] The government and STC also swapped prisoners in Aden, Abyan and Shabwa.[62] However, the January 31 full implementation deadline was missed before tensions flared again the following month. In February, the STC once again suspended its participation in the Riyadh Agreement implementation committees and escalated its rhetoric against the Yemeni government and, notably, Saudi Arabia.[63] The breakdown in cooperation followed a standoff on February 8 during which STC-aligned Security Belt forces at Al-Alam checkpoint east of Aden prevented government troops from entering the city and deploying to Lahj governorate – a hotbed of STC support – unless government-aligned Presidential Protection Forces also withdrew troops from Shaqra – a town that sits on the strategic coastal road in Abyan governorate.[64] Following the incident, the STC withdrew from the committee coordinating military deployments.[65] STC-affiliated activists and journalists also accused Saudi Arabia and the Yemeni government of conspiring to overthrow the STC in Aden and supporting terrorism. The direct criticism of Riyadh marked a change from the STC and its affiliates, which have usually followed a script of praising the UAE – its primary backer – while voicing appreciation for Saudi Arabia.[66]

As of late February, the Yemeni government and STC appeared closer to restarting open conflict than implementing the power-sharing arrangements laid out in the Riyadh Agreement. In a grim harbinger of the prospects for the deal, the only achieved benchmark of the Riyadh Agreement since November 2019 – the return of the Yemeni government to the interim capital in the form of Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed – was reversed after the prime minister left for Riyadh on February 12 and had not returned to Aden by month’s end.[67]

Political Developments in Brief:

- January 16: Yemen’s telecommunication company said an internet blackout that struck the country was due to a cut in a key telecommunications cable in the Red Sea. Internet connectivity issues continued throughout the month and into February.[68]

- February 15: Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan al-Saud, speaking at the Munich Security Conference, said Riyadh remained committed to its backchannel talks with the Houthi movement despite the recent uptick in violence in the country and that negotiations were progressing, but noted that the talks were not yet ready to move to “the highest level.”[69]

Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments

Saudi Announces Trials for Air Raids on Hospital, Wedding, School Bus

The Saudi-led military coalition in February began court proceedings against coalition military personnel suspected of breaching international humanitarian law in Yemen in the first cases of their kind.

Speaking in London, coalition spokesperson Colonel Turki al-Maliki said the joint command of the coalition had referred the results of investigations into suspected IHL violations to coalition member states, Saudi state media reported.[70] He did not say how many suspects were on trial or their nationalities.

The Guardian reported that air crewmen were being tried in relation to three airstrikes: an attack on a hospital supported by Medecins Sans Frontieres in August 2016 that left 16 people dead; an attack on a wedding party in Bani Qais that killed 20 people in April 2018; and the August 2018 bombing of a bus in Dahyan that killed more than 40 schoolchildren, most of them under the age of 10.[71]

The trials are based on investigations by the Joint Incident Assessment Team (JIAT), which was established by Saudi Arabia. The Group of Eminent Experts, a UN-appointed investigative panel, has raised concerns about the independence, impartiality, credibility and transparency of the JIAT.[72] In its September 2019 report, the group noted the JIAT’s failure to expressly hold the coalition responsible for any violations, instead blaming human error in the targeting process or technical mistakes in a few cases.

First ‘Mercy Flights’ Carrying Critically Ill Depart Sana’a Airport

Yemeni patients were evacuated by plane from Sana’a in early February for the first time in more than three years, to receive life-saving treatment in Amman. Of 28 patients flown to the Jordanian capital on February 3 and February 8, most were women and children with cancer, kidney disease and congenital anomalies, according to the World Health Organization.[73] The Saudi-led military coalition controls Yemeni airspace and has prevented flights departing from Sana’a International Airport since August 2016.

The UN health agency said on February 9 that a third group of patients would be flown for treatment to Cairo in the coming weeks, but no flight had departed by the end of the month. The UN covers the cost of treatment as well as flights and accommodation for the patients and their family members, but it requires states willing to receive Yemeni patients. According to estimates by the Houthi-run health ministry, 32,000 Yemenis died waiting for specialist medical care abroad.[74]

Saudi Arabia and the Houthi movement have been engaged in backchannel talks since November, and discussions have included the reopening of Sana’a airport. It is not clear if the medical flights were an outcome of these talks. WHO said the flights were made possible through negotiations by UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths, UN humanitarian coordinator Lise Grande and the governments of Jordan, Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

Civilian Casualties Climbing, More than 35,000 newly displaced, Hospitals Hit

Fighting along several front lines has reversed a recent decline in civilian casualties, according to the UN’s humanitarian chief,[75] while forcing more families from their homes and damaging two medical facilities.[76]

In a briefing to the UN Security Council, Mark Lowcock said at least 160 civilians had been killed or wounded in recent violence, and noted reports of children shot by snipers, homes and farms being damaged or destroyed and civilian deaths in Taiz, Hudaydah and Sa’ada governorates. Separately, the UN’s humanitarian coordinator for Yemen, Lise Grande, said February 15 airstrikes in Al-Jawf killed 31 civilians and injured 12.[77]

Al-Jafra Hospital, the main hospital in Majzer district of Marib, was hit February 7 along with a nearby mobile clinic, Al-Saudi field hospital, according to a report from the UN humanitarian coordination agency. Al-Jafra’s intensive care, occupational therapy and inpatient units as well as the pharmacy were badly damaged.[78] Fighting already had closed the facilities prior to the damage, however a paramedic was injured at the mobile clinic. Battles in Marib and neighboring areas escalated in mid-January, and aid agencies providing emergency food and shelter supplies said more than 35,000 people had been displaced since then.[79] (See ‘Fierce Fighting Between Houthi, Govt Forces in Various Governorates’ above for details.)

Three Egyptian Fishermen Killed by Sea Mine, 32 Others Freed From Houthi Jails

Saudi Arabia blamed Houthi rebels for the deaths of three Egyptian fishermen whose boat hit a mine February 5 and sank in international waters of the Red Sea. Coalition spokesman Colonel Turki al-Maliki said in a statement that coalition naval forces rescued three others aboard. Thus far, he said, 137 Houthi-planted mines have been found and destroyed in the southern Red Sea and Bab al-Mandab Strait.[80] Just one day earlier, Houthi authorities released and sent to Cairo 32 Egyptian fishermen who had been detained since the Houthi coast guard accused them of illegally entering territorial waters in mid-December, according to The Associated Press.[81] Egypt is a minor partner in the Saudi-led military coalition that is trying to defeat the Houthis.

Amid Coronavirus Outbreak, Yemeni Students Still Stuck in Wuhan

The Yemeni embassy in Beijing announced that Yemeni students would be evacuated from Wuhan, the Chinese city at the epicenter of the coronavirus epidemic, on March 1. The students would be flown to the United Arab Emirates, where they would be placed in quarantine before returning to Yemen, the embassy said in a circular on February 28. Earlier in the month, the Yemeni government’s foreign minister, Mohammad al-Hadhrami, had thanked Abu Dhabi for offering assistance to evacuate Yemenis stranded in Wuhan.[82]

The Yemeni community in China is estimated to number around 20,000.[83] A Yemeni student in China, who has been in contact with the Yemeni embassy in Beijing, said there were no up-to-date figures on the number of Yemenis in the country. The Yemeni population in China has grown over the past two years with the arrival of Yemenis who were deported from Saudi Arabia, he told the Sana’a Center.

The embassy set up an online group in mid-February for Yemeni students in Wuhan, which 178 people have joined. Most Yemenis studying in China are based in Guangzhou City, and the Yemeni student union there is collecting personal information from Yemeni students to create a database, he added.

No coronavirus cases have been confirmed in Yemen. Deputy Prime Minister Salem al-Khanbashi said fever detectors would be installed at all entry points and a quarantine facility set up at Al-Sadaqa hospital in Aden.[84]

The World Health Organization has declared the coronavirus outbreak a public health emergency of global concern. While it remains possible to contain the virus, all countries must prepare for a potential pandemic, the WHO director-general said on February 26.[85]

International Developments

At the United Nations

Security Council Splits on How Strongly to Rebuke Houthis

The United Nations Security Council extended sanctions on Yemenis considered a threat to security and stability in a 13-0 vote, but rare abstentions from Russia and China drew attention to a contentious split on how strongly to call out the armed Houthi movement for its tactics on and off the battlefield.[86] In adopting Resolution 2511 (2020) on February 25, the UNSC also extended the mandate of the Panel of Experts, which investigates potential sanctions breaches, for an additional year.[87]

The resolution extends an arms embargo against the Houthi rebels that has been in place since April 2015, soon after Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates led an Arab military coalition into the war to help restore the internationally recognized Yemeni government to power. Russia’s objections centered on proposed items singling out the Houthis more than other actors and its desire to limit the resolution to a simple renewal of previous measures, diplomats confirmed to the Sana’a Center.[88] Council divisions have deepened over the Houthi authorities’ treatment of aid workers and its pressure on UN agencies trying to deliver aid, they added, with some members arguing that the UNSC needs to take a strong stance.[89]

The UK, penholder on the Yemen file at the UNSC, and the United States are the Arab coalition’s key international allies in fighting the Houthis; in the Security Council, Russia historically has acted as a check on any attempts to single out Iran, which supports the Houthis. Generally, however, Russia has voted with the rest of the UNSC on Yemen issues and has noted its support for the work of UN Special Envoy to Yemen Martin Griffiths, a former British diplomat. A divided council could hamper Griffiths’ work if he ends up being viewed as the joint US and UK envoy to Yemen, rather than the UN’s envoy.

The UNSC members’ working relationship on Yemen issues, if sometimes uneasy, has rarely grown publicly heated. Left to fester, it could lead to further Russian abstentions, weakening the council’s authority, or even prompt the Russians to use their veto power to block such resolutions. Russia last vetoed a UNSC draft resolution two years ago, blocking what was meant to be, like this month’s resolution, a routine extension of the sanctions committee and experts panel. The February 27, 2018, draft accused Iran of supplying weapons to the Houthis. After vetoing it, Russia proposed and the council passed a straightforward extension that dropped the Iran reference.[90] Whether to include a reference to Iran or to the similarity of Iranian-manufactured arms to Houthi weapons was at issue in the recent pre-vote discussions, according to What’s In Blue, which closely follows and analyzes UNSC activities.[91] A diplomat confirmed to the Sana’a Center that referencing Iran was one issue at play;[92] ultimately, no references were included in a general plea for all to comply with the UN’s targeted arms embargo.[93]

After the Russian and Chinese abstentions, the UK’s permanent representative to the UN, Karen Pierce, complained her delegation had compromised away from its ideal text so the UNSC could speak with authority. “I hope this does not herald a shift in the way the Council does business,” she said.[94] Russia’s envoy, Vassily Nebenzia, shot back, accusing the council of not taking Russian objections seriously during the drafting process. “Many contentious issues were incorporated into the initial draft resolution,” he said, adding delegations were not allowed to “participate on equal footing” to balance the text. Nebenzia, advising the UK to act fairly as penholder of the Yemen file, warned that Russia expects its concerns to be considered going forward or “this will impact on our voting positions.”[95]

China’s representative, Wu Haitao, said his country abstained because the final text failed to meet his delegation’s expectations, even though China had proposed many amendments.[96]

Negotiations on the text were reopened in the hours ahead of the vote, apparently resulting in some of the compromises made.[97] In the end, Resolution 2511 expressed “serious concern” about the impeding of humanitarian aid, “including the recent interference in aid operations in Houthi-controlled areas as well as obstacles and the undue limitations on the delivery of vital goods to the civilian population occurring throughout Yemen.” It also singled out the Houthis by noting the UN needs access to the SAFER oil terminal offshore of Houthi-controlled northern territory.[98] Houthi authorities have barred checks on the decrepit facility, which is feared to be at risk of spilling 1.14 million barrels of oil into the Red Sea.[99] It condemned conflict-related sexual violence in Houthi-controlled areas as well, while in the same point condemning the recruitment and use of child fighters “across Yemen.”[100] UN investigators and human rights groups have recorded the conscription of children by Houthi and government-affiliated forces, but numbers have skewed heavily to Houthi recruitment.[101] The resolution also singled out Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and Islamic State group, but otherwise tended to avoid specifying a party or else included all parties.[102]

UN-Appointed Experts Report on Sanctions Breaches, Arms Investigations

UN-appointed experts reported January 27 on breaches of sanctions and continued violations of international humanitarian and human rights laws by all sides. The Panel of Experts for the UN Security Council’s (UNSC) Yemen Sanctions Committee also concluded in its annual report that the armed Houthi movement did not carry out a claimed September 2019 attack on Saudi Aramco oil facilities that upset global oil markets. The US has blamed Iran.

The Panel of Experts is tasked with gathering information related to the implementation of UNSC sanctions under Resolution 2140 (2014), including asset freezes, travel bans and targeted arms embargoes. The experts cited weak oversight at the government-run Central Bank of Yemen in Aden as providing vast opportunities for corruption, while the absence of central bank compliance enforcement has facilitated Houthi sanction evasion. As well, revenues collected in Marib, Al-Mahra and Hadramawt, governorates nominally under government control, which were due to the central bank in Aden had instead been appropriated to enrich local leaders, the panel said.

The panel also reported that funds from accounts held by the Al-Saleh foundation, which listed Ahmed Ali Saleh, son of the late former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, as its sole beneficiary had been transferred to the Houthis in violation of the assets freeze.[103] Ahmed Ali Saleh, who has been living in the United Arab Emirates, is on the UN Sanctions list. When the experts informed the banks they were obligated to comply with the sanctions, they said they were told the Houthis had “compelled the banks to transfer funds from these accounts to the Houthis.”[104]

The Panel of Experts had limited access to Yemen, completing two visits to Aden and Al-Turbah, Taiz governorate; two planned trips in September and November were canceled for security reasons. Despite repeated attempts, investigators were unable to travel to Houthi-controlled areas. The report noted in particular that lack of access impeded conclusions related to weapons investigations, as arms inspections require viewing “arms captured on the battlefield or seized in transit as close in time to the point of capture or seizure as possible.”[105]

During their investigations, the experts visited Saudi Arabia to inspect weapons debris from Houthi-claimed cross-border attacks. While confirming the Houthi movement was responsible for long-range attacks on targets in Saudi Arabia, the report notably concluded they lacked the requisite range to carry out the Aramco strikes and said the direction of attack made it unlikely it had originated in Yemen.[106] However, the experts conceded the same type of weapons as used in the strikes had been launched previously from Yemen into Saudi Arabia.

The Panel also investigated acts suspected of violating international humanitarian law and human rights law. On the Yemeni government and the Saudi-led coalition side, the Panel investigated eight airstrikes that killed approximately 146 people.[107] It also documented cases of arbitrary detention and enforced disappearances, providing details to UNSC members in a confidential annex. The panel noted that it has not received any response to letters it has sent to Saudi authorities since 2016 requesting information about certain airstrikes. The report concluded that in several instances the principles of proportionality and precaution were not respected.[108] On the Houthi side, the panel documented arbitrary arrests and detentions, ill-treatment, torture and lack of due legal process for prisoners; it also noted that the number of victims from Houthi explosive ordnance, most notably landmines, had increased in 2019.[109]

The report carries several recommendations to the UNSC and the Sanctions Committee. It urged language demanding that the Houthis take specific measures to comply with UN sanctions, adhere to anti-money laundering statutes, cease unlawful appropriation of funds for their own military support and stop arresting and intimidating bank managers and staff.[110] It also recommends that the UNSC send a letter to the members of the Saudi-led military coalition urging them to adhere to international humanitarian law, and that the Yemeni government should investigate reports of alleged illicit enrichment by public officials.

On February 25, the UNSC extended the panel’s mandate for an additional year, with specific instructions to include information about commercially available components used to assemble drones, sea mines and other weapons systems — measures clearly aimed at the Houthis. However, the council urged care in meeting the request without harming humanitarian aid efforts and legitimate commerce.[111]

At the UN in Brief:

- January 13: The UNSC’s first order of business on Yemen in 2020 was to adopt Resolution 2505 (2020), renewing the mandate of the UN Mission to Support the Hudaydah Agreement (UNMHA) through July 15.[112]

- January 16: Saint Vincent and Grenadines, Tunisia, Niger, Vietnam and Estonia began their two-year Security Council terms in January, sounding very much like the rotating members they replaced on the subject of Yemen. Initial statements from the new members called for an end to the humanitarian crisis and a commitment to the Stockholm Agreement. Estonia, as its European allies have in the past, also expressed deep concern about gender‑based violence.[113]

In the United States

US Extends Temporary Protected Status For Yemen, Deportation Risk Remains

The US Department of Homeland Security has extended the Temporary Protected Status (TPS) designation for Yemen until September 2021.[114] TPS gives legal status to an estimated 1,250 Yemeni nationals based in the US, according to Oxfam.[115] While the extension protects Yemenis who arrived before January 4, 2017, the US government did not redesignate Yemen’s status, meaning those who came after that date remain at risk of deportation.

The status of many Yemeni nationals in the US is precarious, particularly in the face of the Trump administration’s unyielding immigration policies. In late January, wildlife photographer Hazaea Alomaisi, was abruptly deported by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) after 22 years living in the US.[116] Alomaisi’s lawyer said that authorities had issued a final order for his return to Yemen in 2006, but had not acted on it until now.

Democrat Candidates United In Opposing US Support for Saudi-led Coalition

As the Democratic primaries kicked off, there was one area that almost all of the presidential hopefuls appeared to agree on: ending support for the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen.[117] Senator Bernie Sanders, who was the frontrunner in the polls at the time of writing, led the charge in the Senate last year to end US involvement in the conflict using legislation based on the War Powers Act.[118] [119] Former Vice President Joe Biden said he would end US support for the coalition and make Saudi Arabia a “pariah.”[120] Senator Elizabeth Warren also called for an end to the US role in the Yemen conflict, which she said made America “complicit” in the country’s humanitarian crisis.[121] Pete Buttigieg, a former city official, also cited the humanitarian disaster in Yemen in explaining why he believed the US should end military support for the coalition.[122]

Billionaire businessman Michael Bloomberg, a latecomer to the race, appeared less strident when asked about US-Saudi relations in light of the 2018 murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul and Saudi involvement in Yemen.[123] He told the Council on Foreign Relations that the US-Saudi relationship was “critical,” citing threats from Iran and the need for stability in energy markets. He did add, however, that he would pressure Riyadh on the Yemen conflict and its human rights record, saying that US President Donald Trump had given the kingdom a “blank cheque.” Still, Bloomberg is on record publicly praising Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in September 2019 even after he was directly implicated in the Khashoggi killing.[124]

Eight candidates remained by the end of February out of an initial Democratic Party pool of 29. Party delegates will choose their nominees for president and vice president at the Democratic National Convention in mid-July ahead of the November election.

Developments in the US in Brief:

- February 2: Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) claimed responsibility for a shooting at a US Navy base in Pensacola, Florida, in December that killed three people and injured eight more.[125] A recording released by AQAP claimed the militant group had directed Saudi national Mohammed Saeed al-Shamrani to carry out the attack.

- February 7: Sudan said it would compensate families of those killed in the Al-Qaeda bombing of the USS Cole while it was refueling in Aden’s port in 2000, killing 17 US sailors and injuring 39.[126] The US has long claimed that the attack on its navy destroyer would not have been possible without Sudan’s hosting of then-Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden in the early 1990s. The Sudanese state-run news agency SUNA quoted the justice ministry as saying the move was part of efforts to remove Sudan from the US State Sponsors of Terrorism list, following Omar al-Bashir’s deposal as president in April 2019. However, it denied any government responsibility for the bombing. Days later, the Sudanese government said it had agreed to hand Al-Bashir over to the International Criminal Court to stand trial for war crimes and genocide.

In the Region

Where is Saudi Arabia Headed in Yemen?

Commentary by Thomas Juneau

Saudi Arabia launched its military intervention in Yemen in March 2015, initially at the head of a coalition of 10 states, with the official objective of re-establishing the government of President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi in the capital, Sana’a, from where it had been expelled the previous September by the Houthis. Five years later, Saudi Arabia is now stuck in a quagmire: the frontlines have barely moved since the coalition, along with its local partners, pushed the Houthis out of Aden in the early months of the intervention. The war has been excessively costly for Riyadh, not only militarily and financially but also diplomatically. What does 2020 hold for Saudi Arabia’s role in Yemen?

The scope and scale of Saudi Arabia’s military intervention in Yemen has to be seen in the broader context of the revolution in its foreign policy in the wake of the ascendancy of Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) in early 2015.[127] In the short period between 2015 and 2018, the previously cautious Kingdom launched a brutal war in Yemen, led the blockade of its neighbor Qatar,[128] initiated a diplomatic spat with Canada,[129] kidnapped the Lebanese prime minister and forced him to resign on television, and assassinated a prominent critic, Jamal Khashoggi, at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

It is striking, however, that MBS has not launched comparably reckless foreign policy adventures since late 2018, and that his aggressive and ambitious rhetoric has toned down. Why is that the case? Arguably, there has been a growing realization that the country’s foreign policy since 2015 was increasingly costly, and that this was unsustainable in the long term. How this learning process came about, however, is not clear: whether MBS truly understood the costs of his actions and concluded he needed to slow down his ambitions remains a matter of debate, as is the role that his father, King Salman, and senior advisors played in moderating the impetuous Crown Prince’s ambitions.

The sudden shift in Saudi foreign policy has partially reversed since the assassination of Khashoggi in October 2018, but this does not imply a return to the pre-2015 status quo. Indeed, adventurist regional endeavors continue, even if new wars have not been launched: the diplomatic and economic embargo of Qatar and the war in Yemen, in particular, show little sign of abating.

What does this partial recalibration mean for Saudi involvement in Yemen? Riyadh wants to remain involved in Yemen, but it also wants to lower the costs of its intervention. This is, of course, far easier said than done, and Saudi Arabia has yet to devise and implement a strategy that would allow it to do so.

Riyadh, first, cannot afford to withdraw completely from Yemen, given the geo-strategic importance of the latter to the former and the 1,800 kilometer border they share; it is rather looking to recalibrate its role. Riyadh still perceives, in particular, that its support is vital to ensure the survival of the loose and heteroclite coalition supporting President Hadi, which includes the Islah party, some remnants of the General People’s Congress (the party of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh), and a diverse array of tribal militias, business interests, and loyalist units in the military and security services. Riyadh believes, correctly, that its sudden withdrawal would lead to the weakening or the disintegration of this coalition, which would benefit the Houthis – and their external benefactor, Iran.

At the same time, Riyadh wants to reduce the costs of its intervention in Yemen. It has come to realize, in particular, that the financial and military costs are unsustainable[130] and that the diplomatic costs – in terms of its image in the West, both in the media and in political circles – are mounting. This, in turn, complicates its ability to leverage its close partnerships with Western governments, which it views as essential to its security. This could become especially true in the case of Saudi Arabia’s most important relationship, that with the United States, where frustration with Riyadh is gradually mounting. This is true in Congress, where opposition to the war in Yemen has become an area of bipartisan cooperation, and even more so throughout the Democratic Party. Should a Democrat win the presidential elections in November 2020, in particular, Saudi-US relations could be in for a rough ride.

Devising and implementing this recalibration is a very hard balancing act to strike, one which Riyadh has failed to achieve so far. Engineering such a change in policy, first, is complex, and made more difficult by Saudi’s weak bureaucratic and institutional capacity. Second, perhaps the greatest challenge for Saudi strategy in Yemen is Hadi himself. Riyadh has completely tied its fortunes to him; as president of the internationally-recognized government, he leads the coalition that Saudi Arabia supports to counter the Houthis and Iran. Hadi is, as such, indispensable. He is, however, weak, corrupt, and ineffective. This poses a major constraint on Riyadh’s ability to achieve its objectives in Yemen.

A related problem for Riyadh is that the anti-Houthi front is weak and fragmented, with Hadi as its leader in name only, further reducing its leverage in talks with the Houthis. As such, Saudi Arabia has actively sought to bolster the unity and strength of pro-government forces, notably with the Riyadh Agreement in the fall of 2019. But this accord, which aimed to integrate the separatist Southern Transition Council into central government structures, has largely failed.[131]

Looking forward, Riyadh will continue, and probably intensify its efforts to unify and build up the anti-Houthi front, but prospects for success are low given its fragmentation and Riyadh’s absence of alternatives to Hadi. As such, the most likely scenario for Saudi involvement in Yemen in 2020 is a continuation of the status quo.

Thomas Juneau is an assistant professor at the University of Ottawa’s Graduate School of Public and International Affairs and a non-resident fellow at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. He tweets @thomasjuneau.

US Kills Quds Force Leader, Targets Iranian Commander in Yemen

Tension between Iran and the US peaked in January with the targeted killing of Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Major General Qassem Soleimani in a US airstrike near Baghdad airport.[132] Soleimani was head of the Quds Force – a military unit responsible for the IRGC’s overseas operations, including coordination with allied non-state actors in the region. Nine others were killed in the strike, including Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis – leader of the Iranian-backed militia Kataib Hezbollah. Iran responded January 8 with a missile attack on two Iraqi military bases housing US troops.[133] The Pentagon initially said there were no casualties, though it later revised this assessment, saying that more than 100 US service members had sustained traumatic brain injuries in the attack.[134]