By Marta Colburn

Throughout six years of conflict, Yemeni civil society organizations (CSOs) have sought to contribute to humanitarian response efforts in a dynamic crisis. However, they have faced considerable challenges in playing a leadership role in response efforts, building meaningful partnerships with international organizations and directly accessing donor resources. Despite commitments to localization, enshrined in the Grand Bargain and the Charter for Change, the international community has failed to support Yemeni civil society to prepare for a role following the conflict, while parties to the conflict have often manipulated organizations in a highly politicized context.

There are a wide range of barriers detracting from donor support to Yemeni CSOs resulting in a lack of accountability to commitments to the localization of humanitarian action. This has limited the sector’s ability to address needs and build a foundation to respond to future needs. Partnerships between international organizations (UN agencies and international non-governmental organizations, INGOs) and local entities, including government and quasi-governmental organizations, have been essential in humanitarian response efforts and mitigating the impact of the conflict in Yemen. However, international organizations have also failed to fulfill their commitments to localization in Yemen, a reality that some UN agencies and INGOs have recognized.

Meanwhile, in the wake of the conflict the recognition by the Yemeni government of the positive role of civil society has been substantively undermined. Parties to the conflict have too often instrumentalized local CSOs. In Yemen, like other conflict-affected settings, the war has disrupted normal government services and fragmented governance and rule of law processes. With parties to the conflict using violence and the force of arms to pursue their military objectives and political agenda, civic space has diminished throughout the country; civil interactions in active conflict zones have been particularly hard hit.

All CSOs have felt the impact of the conflict on the economy with: complexity in bank transfers; dramatically fluctuating currency exchange rates in various parts of the country; the general plummeting value of the Yemeni rial; and inconsistent availability of hard currency in the market or banks to pay staff salaries and vendors in dollars. Financial sanctions on Yemen present a major challenge for all organizations operating in the country, but at times they have had a crippling impact on local organizations. The US State Department’s recent move to designate the armed Houthi movement, also known as Ansar Allah, as a Foreign Terrorist Organization is likely to have a devastating impact on humanitarian response efforts and exacerbate existing high levels of food insecurity contributing to the looming shadow of famine in the country.

This policy brief presents the challenges and insights of various key stakeholders on Yemeni civil society during the current crisis. Drawing from 41 interviews conducted with donors, international organizations, Yemeni civil society activists, researchers and scholars, as well as an online survey completed by 19 Yemeni CSOs from throughout the country, this brief explores the challenges that restrict donors and international organizations from developing meaningful partnerships with local CSOs. It also looks at the range of barriers to local CSO leadership in the humanitarian-development-peace nexus from internal issues to contextual challenges.

The following recommendations are designed to contribute to a conversation on how to invest in Yemeni civil society to address declining humanitarian funding and contribute to CSO sustainability. An additional factor shaping the following recommendations is to seek to create a more lasting impact in the country by building on the massive investment in humanitarian response by the international community over the past six years.

To Donors

To International Organizations

To Yemeni Civil Society Organizations

To Government and Local Authorities

Yemen has close to a century of history of formalized civil society.[1] Four distinct openings[2] have seen significant expansions of civil society: 1) the establishment of formal entities and informal associations during the British colonial era in the South;[3] 2) the cooperative movement in the 1970s and 1980s in the North; 3) following Unification in 1990 there was a political opening with the establishment of democratic processes fostering the growth of formal civil society organizations; 4) and following the Arab Spring until the conflict began there was a thriving of Yemeni non-profit organizations registered with the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor (MOSAL).[4] Indigenous traditions in the country have contributed to these openings through collective action, charitable giving and tribal associational patterns.[5] Additionally, the country’s egalitarian, consultative and freedom of expression practices have shaped such eras and strengthened civic interactions. Finally, aspirations for political participation in diverse segments of Yemeni society played a distinct role in the emergence of civil society during each of the four openings as Yemenis demanded political change from those in power.

Yemen’s legal context for civil society is regulated by the Law on Associations and Foundations (Law 1 of 2001) and its 2004 by-law,[6] considered the most enabling on the Arabian Peninsula.[7] This legal framework governs the work of unions,[8] foundations and association, cooperatives, and even formal Water User Associations. According to the 2018 edition of the Civil Society Sustainability Index, by the end of year the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor estimated that approximately 13,200 civil society organizations (CSOs) were registered throughout Yemen, although this number also includes those who were inactive.[9] The Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor provides the legal rubric for many such organizations, with the work of youth organizations coming under the Ministry of Youth and Sports, and local councils under the Ministry of Local Administration. Although the Law of Associations and Foundations does not include a legal framework for registering networks,[10] the impulse of Yemeni organizations to work together, fueled by donor support, is reflected in the 96 networks identified in a 2013 World Bank study.[11]

With the crisis, many CSOs have felt compelled to evolve and contribute to humanitarian response efforts. While some failed to navigate this transition, others are alleviating the suffering of Yemenis caused by the conflict and the humanitarian crisis. Throughout the crisis new organizations continue to be established, including some associated with parties to the conflict. Other CSOs have arisen from a sense of activism and the desire to contribute to social justice, social cohesion and peacebuilding. However, local CSOs face considerable challenges in playing a leadership role in response efforts, building meaningful partnerships with international organizations and directly accessing donor resources.

Yemeni civil society has been deeply impacted by the eruption of the conflict. A survey among Yemeni CSOs in 2015 found that 60 percent had encountered violence, looting, harassment or had their assets frozen.[12] Organizations have faced a wide range of challenges including: security and safety risks, such as detention, extortion, assault, kidnapping, attempted assassination and assassination of staff by armed groups and individuals; reputational risks, with organizations and activists suffering from smear campaigns seeking to undermine activism; and constraints to freedom of expression and freedom of assembly.[13]

The conflict and humanitarian crisis have focused donor attention on Yemen, and UN agencies and international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) have expanded their programming and teams. For many international organizations their Yemen portfolios constitute their largest budgets and levels of expatriate and local staffing. International organizations have also been hard hit by operational challenges in a deepening humanitarian crisis. It is anticipated that when a political solution is reached, many international organizations will scale down and local institutions will play an essential role in addressing ongoing humanitarian needs.

Rebuilding efforts will require a strong Yemeni civil society in order to repair the social fabric, contribute to transitional justice and provide services to vulnerable members of society. Yet, the international community has failed to support civil society to prepare for this role and parties to the conflict have often manipulated organizations in a highly politicized context.

Recently there have been a few publications exploring various challenges faced by civil society in Yemen, with a number focusing on topics related to CSO involvement in peacebuilding.[14] This policy brief was developed in an effort to draw attention to critical aspects of the relationship between Yemen CSOs, international organizations and donors and to put forward some recommendations to address the question, “What can the international community do to support Yemeni CSOs to take on a broader leadership role in the coming phase?”

In October-November 2020, the author conducted 41 interviews with the following categories of informants: 18 donors (bilateral, multilateral and public and private foundations), 15 international organizations (INGOs and UN agencies), five Yemeni civil society activists and three researchers/scholars. Additionally, an online survey was completed by 19 Yemeni civil society organizations from throughout the country who are participating in the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies Yemen Peace Forum initiative.

The importance of localizing development, peacebuilding and humanitarian action has been a topic of discussion for decades. The World Humanitarian Summit in 2016, which brought together 9,000 participants representing 180 member states and more than 700 local and international NGOs, catalyzed “major changes in the way we address humanitarian need, risk and vulnerability.”[15] A key outcome of the Summit was recognition of the importance of locally-led response efforts. The Summit also endorsed major sets of commitments including: The Agenda for Humanity (2016),[16] the Charter for Change (2015),[17] the New Way of Working[18] and the Grand Bargain (2016).[19] The Grand Bargain is relevant to this brief as it committed donors and aid organizations to provide 25 percent of global humanitarian funding to local and national organizations by 2020, as well as more flexible, unearmarked money and multi-year funding.

There is a consensus that localization is essential to improve the effectiveness, efficiency and sustainability of humanitarian action. However, in a conflict-affected context such as Yemen, there are additional complexities to actualize such a consensus. There are significant risks associated with the lack of local capacity, potential for diversion of resources and challenges in delivering assistance to those most in need.[20] Additionally, there is recognition that life-saving humanitarian action is essential, but that such efforts should be short-term in duration and must be accompanied by robust investments to achieve durable political solutions. A priority identified at the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit was to strengthen the triple nexus of humanitarian-development-peace.[21]

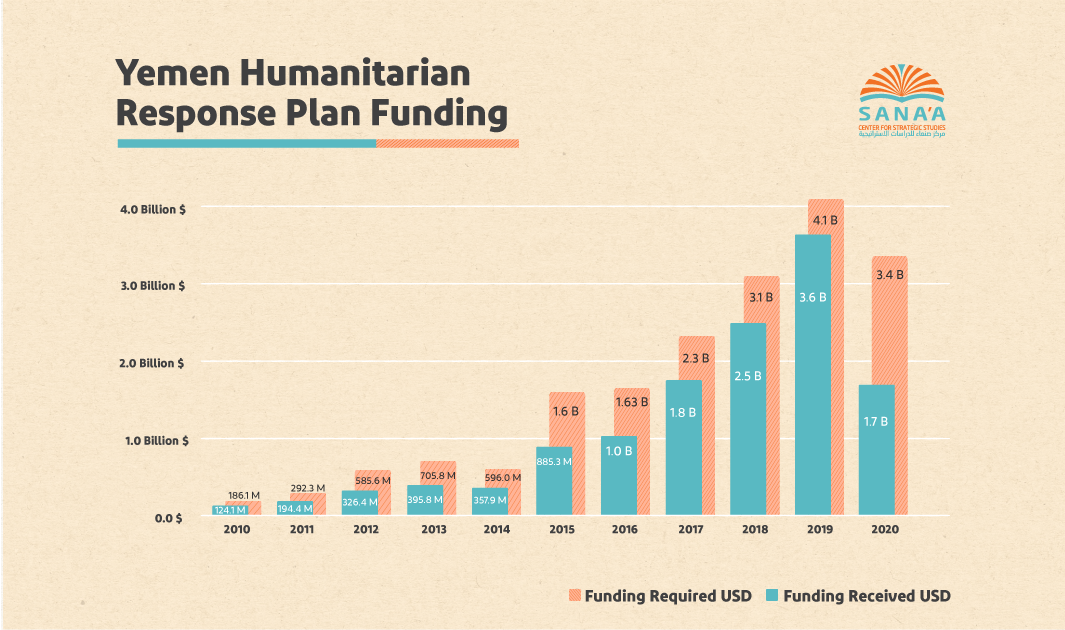

Figure 1: [22]

In 2020, funding to the UN’s Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan dropped significantly, as illustrated in Figure 1, though in 2018 and 2019 contributions saw record highs. The 2020 decrease was primarily due to reduced contributions from Saudi Arabia, the United States, the United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom. While the final figures for 2020 are not yet in, funding outside the Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan has also significantly decreased: in 2018 it was US$2.72 billion, in 2019 US$423.9 million and in 2020 only US$198 million.[23]

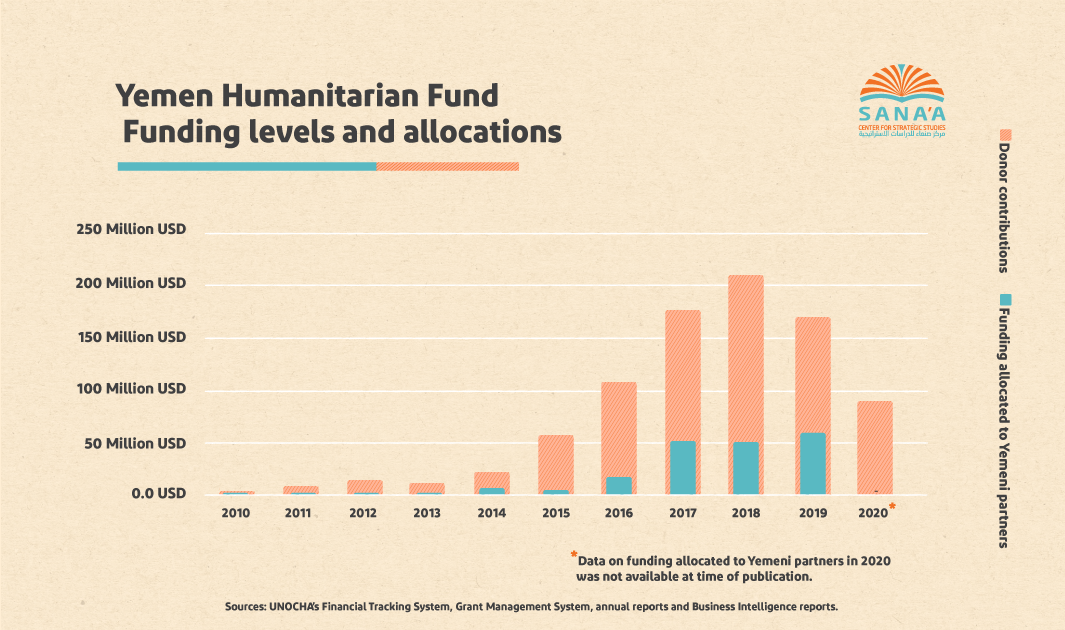

Pooled funding mechanisms bring together contributions from multiple donors and are designed to be flexible and responsive, particularly when earmarked for humanitarian crises. In Yemen there are two such mechanisms that Yemeni CSOs can in theory access: the Yemen Humanitarian Fund (YHF), managed by UNOCHA, and the Peace Support Facility (PSF), managed by UNDP. To date, no support has been provided to local CSOs through the Peace Support Facility.[24] Figure 2 shows support to Yemeni CSOs from the Yemen Humanitarian Fund in the 10 years since it was established; the remainder was allocated to international NGOS, UN agencies and Red Cross societies.

Figure 2:

|

Yemen Humanitarian Fund Analysis |

|||||

|

Year |

1. Annual Contributions (US$) |

2. Funding Allocated (US$) |

3. % of Funding Implemented by LCSOs |

4. % of Projects Implemented by LCSOs |

5. # of LCSO Projects Funded |

|

2010 |

2.5 million |

238,230 |

38 |

67 |

2 |

|

2011 |

8.9 million |

3.7 million |

13 |

20 |

4 |

|

2012 |

13.6 million |

8.5 million |

13 |

14 |

5 |

|

2013 |

11.6 million |

7.35 million |

16 |

29 |

7 |

|

2014 |

22 million |

19.9 million |

30 |

33 |

23 |

|

2015 |

57 million |

50 million |

9 |

23 |

14 |

|

2016 |

107.5 million |

94.1 million |

18 |

33 |

26 |

|

2017 |

175.5 million |

126 million |

41 |

53 |

62 |

|

2018 |

209 million |

188.2 million |

26 |

55 |

58 |

|

2019 |

169 million |

239 million |

25 |

52 |

75 |

|

2020 |

89 million |

98.3 million |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

23% |

38% |

|

Funding to the Yemen Humanitarian Fund has declined since 2018. The percentage of funding to Yemeni CSOs has fluctuated significantly, while the number of projects implemented by local CSOs has steadily increased from 2010 to the latest available figures in 2019.

The important role played by local CSOs in the humanitarian response has led to the observation that the situation in Yemen would be far worse if not for the contributions of local CSOs. In addition to those funded through the Yemen Humanitarian Fund, many other local CSOs are implementing programming from a variety of funding sources. According to UNOCHA, in August 2020 there were 59 organizations active in 300 of the country’s 333 districts.[25] UNOCHA recognized the essential role played by Yemeni CSOs in their 2019 annual report of the Yemen Humanitarian Fund: “We continued to aim for maximum efficiency by prioritizing direct implementation, integration of response in the worst affected areas and support for local partners – part of our unwavering support to the Grand Bargain commitment to localization of aid.”[26]

In interviews for this policy brief, donors and UNOCHA identified a number of perceived challenges with the Yemen Humanitarian Fund’s interventions through international organizations and local CSOs including:

Meanwhile, Yemeni CSO leaders identified key challenges in accessing Yemen Humanitarian Fund resources, as well as other humanitarian funding opportunities, including:

Over the past five years YHF support to local CSOs and INGOs who have received funding for more than three projects within one year (i.e. partner retention rate) is similar, standing at 17 percent and 18 percent, respectively.[31] However, it was noted by UNOCHA staff that the number of local CSOs suspended from receiving further funding due to serious performance issues was higher than among INGOs.[32]

The April 2021 virtual Humanitarian Leadership Conference aspires to reshape the humanitarian ecosystem. It is hoped that this global gathering will compile lessons learned on the localization of humanitarian response efforts, including examining barriers to the leadership of local civil society actors.[33]

While the regional intervention in the Yemen war in March 2015 emerged from in-country conflict dynamics that had been building for many years,[34] 2015 was a watershed point ushering in a massive humanitarian crisis impacting all levels of Yemeni society. As a result of the conflict and the ensuing humanitarian crisis, donors reduced their physical in-country presence, activated a remote management model and significantly adapted their programming priorities, thus constraining their engagement with local actors and their ability to meet their commitments to localization.

Difficulties in traveling out of Yemen are a major factor limiting direct interactions between Yemeni CSOs and donors.[35] This situation restricts the ability of local CSOs to share insights and challenges, engage in advocacy efforts and seek financial support, as well as participate in training, conferences and workshops abroad. With the closure of the Sana’a airport to civilian traffic[36] and difficulties accessing the UN-operated humanitarian flights,[37] Yemenis must travel to Seyoun or Aden for international flights. Prior to the conflict, to drive from Sana’a to Aden took from 5 to 5.5 hours; this journey now can take double or triple the time for various reasons including the proliferation of checkpoints. Travel to access international flights also may mean crossing between areas controlled by different parties to the conflict, with risks depending on a traveller’s name, tribe, social group or political views. Additionally, Yemenis face complex issues to secure entry visas to countries in the region and extreme difficulties to travel to Europe or the United States.

A number of donors interviewed noted that operating from outside the country meant they could not monitor and follow up on local project partners. As one donor noted, “A key challenge we face is having direct contact with local CSOs. The difficulties in travelling regularly to Yemen mean that we work primarily through international organizations who carry out due diligence, monitoring and capacity building with their local civil society implementing partners. We would like to work more directly with local organizations, a situation we are currently seeking to address.”[38]

Also, smaller donors mentioned that with dire humanitarian needs and the urgency to contribute to life-saving efforts, they tend to contribute to UN agencies, pooled funding mechanisms and/or larger well-known international organizations. Investing in a number of smaller grants to local CSOs is very labor intensive, requiring significant due diligence and developing remote monitoring mechanisms, versus funding a larger project through a UN agency or INGO with whom they have a global relationship.

A further issue expressed by a number of donors was the complex process for them to select local CSO partners while outside the country. Open competitive calls for projects can yield an avalanche of proposals which can be overwhelming to evaluate. Some interviewees noted that in such open calls successful Yemeni CSOs may be those most experienced in proposal preparation, but not necessarily the best organization to implement. Other donors noted that the CSO leadership they tend to encounter outside the country are often diaspora-directed organizations whose senior leaders speak English, and who are experienced in relationship management, but who may be less grounded in operations and programmatic gaps and opportunities. It was noted that large open calls may have limited local relevance and only a handful of local CSOs are able to successfully compete, with international organizations mobilizing teams of proposal writers to respond.

Additionally, many donors continue to operate primarily in English, requiring that proposals, reporting and communications are all in English, with limited opportunities for interactions in Arabic. Many Yemeni CSOs have limited English language skills, as well as an absence of resource mobilization and donor relationship management experience, particularly for organizations based outside major cities.

Some international organizations funding programs in Yemen favor working with proven local partners with shared programming values whom they trust. Such approaches are more common with smaller private foundations with specific mandates, therefore narrowing the field of local organizations they could potentially work with.[39] One such foundation reiterated this alternative approach and observed, “Support to our Yemeni civil society partners is more institutional rather than project oriented, though we have very high standards in fiscal stewardship and reporting. A key driver in selecting partners is to support Yemeni voices sharing their insights and analysis in the international sphere. We feel this is essential, particularly when such perspectives are often ignored.”[40]

This section has narrated donors’ perceptions of the constraints to developing more meaningful partnerships in Yemen with local CSOs. There is a lack of donor accountability to agreements related to the localization of humanitarian action. Eight of the top 10 donors to Yemen for 2017-2018 are signatories to the Grand Bargain, with the exceptions being Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.[41] While it is beyond the scope of this study to analyze how much of the massive assistance provided to Yemen has been implemented through local and national responders, it is far less than the 25 percent target in the Grand Bargain.[42] Numerous donors were cognizant of this failure and a number are currently seeking ways to address this challenge. This situation has had a very negative impact on local civil society and limited the ability of this key sector to address needs and build a foundation to respond to future needs in the triple nexus of humanitarian-development-peace.

Partnerships between international organizations and local entities, including government and quasi-governmental organizations,[43] have been essential in humanitarian response efforts and mitigating the impact of the conflict in Yemen. A number of UN agencies work in close partnership with local CSOs, with UNFPA noting that 75 percent of their programming in Yemen is through local NGOs, which constitute 10 of their 16 partner organizations. Approximately 25 percent of UNICEF Yemen’s programming is also implemented in partnership with local CSOs, with 52 out of 211 implementing partners being CSOs. In 2018, UNDP Yemen worked with 25 Yemeni CSOs which accounted for 2.7 percent of their programming and in 2019 it was 2.2 percent, although UNDP’s partnership with the Social Fund for Development and the Public Works Project, national quasi-governmental entities, accounts for about 85 percent of their portfolio.[44] International NGOs also work in partnership with local CSOs, although of those interviewed none reached even close to the 25 percent target of the Grand Bargain.

One of the most significant challenges in fostering enabling partnerships between international organizations and local CSOs is the urgency to deliver life-saving services to highly vulnerable populations. This massive challenge was recognized by all sources for this research as a driving factor in transactional relationships that characterize the outsourcing of humanitarian assistance through local CSOs. Such patterns detract from building meaningful empowering partnerships with local CSOs in Yemen. While the life-saving imperative is clearly recognized by all, many INGOs and UN agencies are neglecting their international commitments to localization, rationalizing such failures with a variety of excuses. Investing in analyzing risks to localization and developing risk mitigation strategies could yield significant improvement in localization efforts.

Constraints to Enabling Partnerships Between International Organizations and Local CSOs

There is a high turnover of international staff in many organizations, with significant time out of the country, in part due to generous “Rest and Recuperation” (R&R) allowances and remote management at times. This revolving door of international staff detracts from them building an understanding of the Yemen context and learning to trust local staff and partners. Yet, decision-making power is often concentrated in the hands of international staff. While at times the presence of international staff can insulate national staff and local partners from pressure by local authorities, over-reliance on such staffing also disempowers locally-led decision-making and restricts building meaningful partnerships with local CSOs. In one interview, staff from an INGO noted that in their internal exploration of localization trends they found that Yemeni and international staff within their organization exhibited hierarchical attitudes toward Yemeni CSOs and failed to recognize the value added from such partnerships.[45]

Other constraints to meaningful partnerships include the transactional nature of project implementation relations between local CSOs and international organizations, at times resembling contracts rather than partnerships, as well as unrealistic and overly cumbersome requirements in procurement policies and processes. As one local CSO interviewee noted, “We’ve been trained in their procurement policies, but they are talking about the moon and we are here on earth.”[46] Other issues mentioned by international organizations that local CSOs face were: a lack of checks and balances; absence of strategic planning processes, policies and procedures which promote inclusion and integrity within organizations; and management decision-making concentrated in what one individual characterized as “leader-for-life syndrome.”[47] Meanwhile, internal challenges faced by INGOs and UN agencies include: attracting a low caliber of international staff, either very young and inexperienced, or those who have few other options; those who are attracted to the high salaries and extra perks; and individuals who may draw inaccurate comparisons with their earlier postings, which can contribute to poor decisions and disempower national staff.

A recent confidential policy brief, seen by the author, by an international organization looking at Women, Peace and Security program challenges identified significant barriers to developing meaningful partnerships between international organizations and their local partners.[48] A key issue was the very limited time for proposal preparation, which did not allow adequate time to build partnerships, cultivate consortia, engage in participative program design and consult with targeted beneficiary groups. The policy brief also noted challenges for both local and international organizations with results-based financing, service contracts, funding modalities (annual funding spending and payment systems) and a lack of budget flexibility.

A number of sources for this research noted that due diligence procedures, specifically counter-terrorism vetting, have negatively impacted humanitarian response efforts.[49] This situation has contributed to a flourishing black market and fueled the war economy and corruption.[50] The 2020 suspension of funding by some donors from activities in Houthi-controlled areas has negatively affected international organizations and local CSOs and reduced assistance to millions of vulnerable Yemenis. A number of interviewees also mentioned the devastation that would ensue to humanitarian response efforts resulting in the suffering and death of Yemenis if the United States designated Ansar Allah as a foreign terrorist organization.[51] The designation was ultimately passed in the final days of US President Donald Trump’s administration in January 2021, to the dismay of aid organizations.[52]

At times international organizations’ processes to identify local implementing partners lack transparency. While bias on the part of Yemenis within international and local organizations was noted in this research, the absence of Yemeni voices in decision-making in some UN agencies and international organizations was also highlighted. This lacuna has negatively impacted humanitarian response and peacebuilding efforts and was seen by a number of interviewees as far more insidious and destructive than the perceived Yemeni bias.

It was observed by numerous local and international interviewees for this research that often UN agencies and INGOs are risk averse, and reluctant to jeopardize their programming by confronting local authorities on issues of interference or compromises in independence, neutrality and impartiality. While it is a difficult balancing act, there is generally a lack of advocacy efforts to push back with local authorities when there is undue interference.

The important roles of both local and international actors in delivering humanitarian action are reflected in the UN Secretary-General’s call at the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit for such efforts to be “as local as possible, as international as necessary.” However, international organizations have failed to fulfill their commitments to localization, a reality that some UN agencies and INGOs interviewed for this policy brief recognized.

Local organizations throughout the country have been affected by a wide range of conflict-related challenges, from financial sanctions to disruption of work by shelling, airstrikes and fighting. All CSOs have felt the impact of the conflict on the economy with: complexity in bank transfers; dramatically fluctuating currency exchange rates in various parts of the country; the general plummeting value of the Yemeni rial;[53] and inconsistent availability of hard currency in the market/banks to pay staff salaries and vendors in dollars.

Financial sanctions on Yemen present a major challenge for all organizations operating in the country, but at times they have had a crippling impact on local organizations.[54] While a handful of local CSOs have sought registration outside the country in order to open bank accounts, this is a complex process and not a viable alternative for the vast majority. Civil society has also been hard hit by the departure of many highly qualified CSO activists – some of whom have left the country and others who joined international organizations. This brain drain has bled local CSOs of a significant cadre of management and technical leadership.

Organizations located in areas controlled by the armed Houthi movement have had to deal with additional challenges including increasingly complex requirements to maintain registration and secure project approvals. Local CSOs have also had to secure permission from Houthi authorities for staff travel within the country, as well as to organize gatherings for training sessions or workshops. A further restriction recently seen in some Houthi-controlled areas is requiring gender-segregated training sessions and a mahram (male family escort) for female staff on work travel. One interviewee shared, “Navigating various local authorities in different parts of the country is never easy, it is particularly complicated when working in human rights. In spite of this, Mwatana’s team succeeded to work all over the country and outside Yemen.”[55]

While international organizations face many challenges similar to those encountered by local CSOs, they are generally better resourced, have mitigation measures in place and benefit from a number of advantages over their local peers. Such advantages include: more resources allocated for operational expenses (while local CSOs have to cherish every penny for operations); programmatic, operational and resource mobilization support from regional/global offices; ability to attract a high caliber Yemeni staff given significantly higher salaries, benefit packages, professional development opportunities and technical and operational support; and senior international staff who have stronger management skills and capacities, benefit from generous R&R, and can serve as a buffer in interactions with local authorities.

The 2018 edition of the USAID-funded Civil Society Sustainability Index for the Middle East and North Africa assessed that since the war began there were increased impediments in the overall context for Yemeni civil society.[56] Issues noted in this report included the deterioration of the public image of Yemen CSOs: “positive media coverage was the exception rather than the rule, and officials’ criticism of CSOs and questioning of their loyalty increased, especially in Houthi-controlled areas.”[57] The context for advocacy efforts has been quite limited since 2015, with very few opportunities to advocate publicly around sensitive issues. Due to fighting in 2018, many CSOs in Hudaydah were forced to temporarily suspend activities and in Taiz widespread infrastructure destruction had negative consequences for organizations. However, the report noted that the operating environment for CSOs in Marib and Hadramawt had stabilized. On the positive side, the report assessed that organizational capacity was strengthened in identifying beneficiary needs and meeting donor institutional requirements in the areas of policies, systems and strategies. Additionally, it noted that the financial viability of local CSOs increased slightly in 2018 with improved resource mobilization skills.

One concern repeatedly expressed by civil society activists over the course of this research is that many CSOs have had to shift away from their original mandate focus. While at the beginning of the conflict there were compelling reasons to respond to overwhelming life-threatening needs, the elusive political solution has meant that, with time, many organizations feel increasingly distant from their core values and are exhausted by the short-term and unsustainable nature of humanitarian action. Some local organizations have consciously made the choice not to shift from their core target groups and mandate, but only a handful have succeeded in doing so.

Barriers to Local CSO Leadership

The conflict has resulted in a general narrowing of funding sources for local CSOs and destroyed hard-won fiscal sustainability initiatives. The crisis has devastated household incomes, civil servant salaries and the private sector and also negatively affected charitable giving and earned income opportunities (i.e. participant fees for training or skills building, rental income from facilities for events or workshops, etc.). This has created a context in which local organizations have few sources of funding beyond international grants.

Opportunities for local CSOs to directly access bilateral or multilateral funding are very limited, so most funding comes through UN agencies and INGOs. Directly accessing larger donor funding often requires complex systems and online registration processes, which present particular challenges to younger organizations. Requirements to access funding opportunities include complicated due diligence, eligibility standards and registration processes, and few donors have separate funding streams designated for local CSOs. Additionally, some donors hold back a percentage of the final grant payment until concluding reports are approved, meaning that recipient organizations must have adequate resources to maintain cash flows, which is a challenge for most local CSOs.

Many competitive open application processes pit local and international organizations against one another, rather than promote cooperation. Further, many INGOs share local CSOs’ frustration with only implementing fast-paced humanitarian projects, driving local and international organizations to compete for scarce non-humanitarian funding.

The impact of the conflict on Yemeni civil society has differed among various types of organizations. Organizations focusing on human rights, advocacy, disabilities, culture and the arts have had few survivors from among those who thrived prior to and during the Arab Spring and National Dialogue Conference era. Projects focusing on gender, targeting youth and women or seeking to contribute to peace have, for differing reasons, struggled with limited funding as a result of the conflict. Additionally, organizations have had difficulty in securing permission for such programming from local authorities. Gender programming is particularly complicated in Yemen. One interviewee observed: “It’s not surprising that during times of war that there are sensitivities in homes, communities and with local authorities around such interventions. Local CSOs understand such complex dynamics and are the only ones who can and should lead such programming, with the support of international stakeholders. However, there is often little recognition of such skills among donors and they are rarely aware of the energy and expertise within local CSOs.”[58] While currently there is more funding available for peacebuilding initiatives, most are small in scale and lack the ability to impact the national context. Additionally, due to the stalled UN-led peace process there have been few opportunities for local youth or women to contribute to political solutions.

Prior to the conflict, opportunities for investing in local CSO capacities were limited, but since the conflict there are even fewer, often focusing on a limited group of organizations, a specific sector or location. Additionally, such opportunities are often extremely constrained in scope and budget, and sometimes developed with little local input. Further, a number of local CSOs interviewed mentioned that the selection process for local partners often lacks transparency.

The issue of capacity building can be sensitive. A 2017 study by Oxfam observed: “‘Capacity building’ initiatives are often loaded with power dynamics and their content and format is often poorly tailored to CSO priority needs in conflict settings.”[59] While technical or grant management training is often welcomed by local CSOs, at times there is a misalignment between training opportunities being offered to them and the gaps and needs they have themselves identified. The head of a local CSO noted: “Capacity building is essential, but difficult to translate into an enduring impact on an organization. At Resonate we have developed a number of high impact training packages that we have rolled out to a series of youth cohorts. These have proven very effective, but we have not been able to launch this into a signature program with consistent multi-year funding.”[60]

A further issue identified by local CSOs was negotiating overhead costs for each project contributing to tension between local partners, international organizations and donors. Similar to international organizations, local organizations have been hard hit by higher costs for security, safeguarding,[61] transportation, solar investments for electricity, logistics, etc. Prior to the conflict, percentages for allowable overhead for local CSOs ranged from 5 to 9 percent, with only a small, if any, increase since then despite ballooning costs, in contrast to international organizations that have cost recovery systems to cover such additional expenses.[62] One donor interviewed recognized that, “Local CSOs need core funding opportunities to strengthen administration in addition to project funding. Most funding streams do not recognize such costs. If donor countries want to support localization and promote professionalism in the sector, it is essential to support such legitimate costs.”[63]

One of the most significant issues identified by all stakeholders during this research was the challenge of working in a highly politicized context with shrinking space for civil society. The chairperson of a local human rights organization said, “We continually strive to maintain our independence and neutrality in an extremely complex environment. We rely on a balanced approach of holding the mirror up to all parties to the conflict and demanding their accountability. This is our greatest strength.”[64] Houthi authorities have replaced senior leadership in some local CSOs, interfered with internal management decisions and sought to influence beneficiary lists. Although there has been less interference in local CSO operations in government controlled areas of the country, insecurity and conflict dynamics in Aden and parts of the South have presented complexities in program implementation for both local and international actors.

The highest ranked operational challenge in the online survey among 19 local CSOs was the “increased politicization of civil society as a result of the conflict.” This issue can potentially negatively impact organizations and contribute to the risk of parties to the conflict instrumentalizing local CSOs. Additionally, there has been a proliferation of politically-affiliated organizations established since the war began, a trend in Houthi-controlled areas, emphasized by numerous interviewees. As one diplomat interviewed for this policy brief noted, “In the current political climate, local civil society organizations are judged by parties to the conflict whether they are perceived to be with them, or against them. Independence and neutrality are not seen positively in this polarized context and this is terribly destructive to the broader context of Yemeni civil society and impacts funding to local organizations.”[65]

The irony is that the value added of local CSOs also contributes to donor and international organization concerns about independence and that parties to the conflict will use organizations. Local CSOs are often the only actors with access to conflict-affected areas, which transfers security risks onto them and potentially exposes them to pressure from parties to the conflict. Unsurprisingly, armed groups are not likely to view neutrality, impartiality and independence in the same light as civil society, and can be suspicious of motives they fail to understand. The managing director of a local CSO shared, “Yemeni civil society organizations are caught in the middle. We face challenges with different authorities on the ground. We end up juggling the priorities of those who fund and partner with us, rather than the priorities and programs we feel will have the most positive impact and the needs of beneficiary communities. We have to continually assess, analyze and design creative solutions to operational and programmatic challenges; efforts which are often unrecognized.”[66]

Numerous local interviewees noted that when working through international organizations their contributions were filtered and their creativity limited. While there are risks for donors to work directly with local CSOs, such barriers detract from the potential positive impact of interventions, particularly those led by creative young people. The Yemeni country director of an INGO observed: “We feel that the arts and culture present amazing opportunities for young people to shine and exercise their most valuable assets – their creativity and energy. When we had a competition for short films the ideas presented were so inspiring and following that the number of young people that became filmmakers and local organizations supporting filmmaking increased.”[67]

With broad representation from Yemeni civil society in the National Dialogue Conference it is not surprising that a range of outcomes reference the essential role of the sector in the political transition process and as a key aspect of Yemeni society.[68] For example, in the NDC Good Governance Working Group nearly 6 percent of the decisions presented in the final plenary referenced key roles for Yemeni civil society.[69] A further document highlighting the role of Yemeni civil society is the September 2013 “Partnership Framework Between the Yemeni Government and Yemeni Civil Society Organizations,” which was developed and adopted by the Yemeni cabinet. The objective of the framework was to foster partnership between the government and civil society to advance sustainable development and improve service delivery in Yemen. The four core goals of the framework were to:

Unfortunately, in the wake of the conflict this recognition of the positive role of civil society has been substantively undermined. In Yemen, like other conflict-affected settings, the war has disrupted normal government services and fragmented governance and rule of law processes. With parties to the conflict using violence and the force of arms to pursue their military objectives and political agenda, civic space has diminished throughout the country; civil interactions in active conflict zones have been particularly hard hit.

In 2019, the Houthis’ Supreme Political Council in Sana’a issued Decree No. 201 establishing the Supreme Council for Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and International Cooperation (SCMCHA), abolishing the international cooperation department at the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation and transferring its functions and powers to the Supreme Council.[71] In areas of the country controlled by the internationally recognized Yemeni government, authorities generally continue to play their mandated role with local CSOs.

The CSO Sustainability Index noted that in 2018 there were more impediments in the legal environment for local CSOs, increasing requirements beyond the framework of the Law on Associations and Foundations (Law 1 of 2001). “Authorities in some areas issued new, repressive decrees, while elsewhere oversight by newly-established official entities created confusion and bureaucratic delays…. This included the Houthi authorities in Sana’a issuing a new decree that temporarily suspended registration of new organizations, and began more aggressively enforcing a second decree that required CSOs to obtain permits for each activity they carried out, including training courses and workshops.”[72]

Factors Constraining Authorities’ Relations with Local CSOs

A number of factors contribute to the actions by the government, the Houthis and local authorities which have narrowed civic space as a result of the conflict. Factors mentioned by interviewees for this report include:

While this research was unsuccessful in engaging directly with government officials, or the Houthi authorities, it is clear they have an essential role in enabling the capacities and facilitating the contribution of the sector.

This policy brief has sought to present the challenges and insights of various key stakeholders on Yemeni civil society during the current crisis, including Yemeni CSO activists. The following recommendations are designed to contribute to a conversation on how to invest in Yemeni civil society to address declining humanitarian funding and contribute to CSO sustainability. An additional factor shaping the following recommendations is to seek to create a more lasting impact in the country by building on the massive investment in humanitarian response by the international community over the past five years.

To Donors

To International Organizations

To Yemeni Civil Society Organizations

To The Government and Local Authorities

Nineteen individuals (35 percent female, average age 34 years) participating in the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies’ Yemen Peace Forum initiative completed an online survey for this policy brief about the challenges facing civil society. Responding organizations had a presence in 17 of Yemen’s 21 governorates and Amanat al-Asimah,[74] with some organizations operating in multiple governorates. The following summarizes the findings of the research.

The most significant operational challenges identified by survey respondents were:

In an open-ended question about the most significant challenge facing Yemeni CSOs, respondents most frequently mentioned the following two categories:

The most salient challenges to resource mobilization identified by respondents included:

When asked to identify the importance of a range of skills to strengthen resource mobilization capacities the following were noted:

Regarding organizational capacities that respondents felt would strengthen their organization’s ability to access funding the following were of importance:

52.6 percent of organizations (10 out of 19) were members in some sort of a network of CSOs.

In an open ended question about how organizations had adjusted their operations since 2015, one CSO respondent shared the following: “On a scale from one to ten, I’d say that the work environment for local civil society organizations has changed negatively by 10 degrees, due to the position of de facto authorities in […] governorate which lack sufficient awareness of the field and nature of the work of CSOs.[75] Therefore our ability to exist as a local organization is determined according to that authority’s vision of what they want local organizations to be, which is subject to their whims, or ideological or pragmatic considerations. Without affiliation with the authority and its body for the coordination of humanitarian affairs, activities and projects remained unattainable, as they favored recently established organizations pushed by the de facto authority to replace local CSOs with experience, influence and leadership. This imbalance was reinforced by the approval of the UN and other international institutions that accept the violation of their policies and regulations. They excluded other organizations for not adhering to bureaucratic conditions, but they overlook organizations who were imposed and affiliated with personalities, parties, individual interests, and leading groups in the authority.”

Asked about recommendations for donors and international organizations to strengthen Yemeni civil society to play a more significant leadership role, common themes identified by survey respondents included: provide funding for non-humanitarian activities (9 mentions); training and capacity building of staff (7 mentions); institutional capacity building (7 mentions); and direct donor communications with local CSOs (2 mentions). Respondents also shared the following insights:

About the Author

Marta Colburn has over 35 years of experience in the Middle East leading organizations and supporting relief and development efforts, including 17 years working on Yemen. Marta most recently served as the Country Programme Manager for UN Women Yemen and has had leadership roles with Oxfam, Mercy Corps, CARE International, UNRWA, IBTCI, American Institute for Yemeni Studies and Portland State University’s Middle East Studies Center. As a consultant Marta has worked with various international and local organizations including the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, ADRA, CARE, Oxfam, British Council, IOM, Mercy Corps, Social Fund for Development, Yemeni Women’s Union, Youth Leadership Development Foundation, Silatech, Partners for Democratic Change, IBTCI and ORB International. Marta has a MSc and BA in Political Science from Portland State University and has a strong background in research and evidence-based knowledge products, gender, organizational accountability and transparency and civil society strengthening.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover diplomatic, political, social, economic, military, security, humanitarian and human rights related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

The Yemen Peace Forum initiative is a track II youth and civil society platform facilitated by the Sana’a Center and funded by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This interactive initiative seeks to both invest in building and empowering the next generation of Yemeni youth and civil society actors and to engage them in critical national issues. Building on the Sana’a Center’s core goal of producing knowledge by local voices, this initiative seeks to develop and invest in young policy analysts and writers across Yemen.