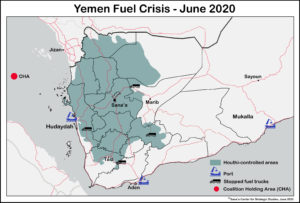

The images are familiar by now: Yemenis in Houthi-controlled territory queue at fuel stations, amid announced shortages. Meanwhile, fuel tankers build up in the Coalition Holding Area (CHA), located in international waters in the Red Sea offshore of Jizan, Saudi Arabia. The number of ships awaiting approval from the government and the Saudi-led coalition to proceed to Houthi-controlled Hudaydah port reaches the proportions of a small flotilla. Combined, these images would seem to tell a simple and compelling story: the Saudi-led coalition and Yemeni government are preventing fuel from entering Hudaydah to spite the Houthis, and ordinary Yemenis are paying the cost.

The images are familiar by now: Yemenis in Houthi-controlled territory queue at fuel stations, amid announced shortages. Meanwhile, fuel tankers build up in the Coalition Holding Area (CHA), located in international waters in the Red Sea offshore of Jizan, Saudi Arabia. The number of ships awaiting approval from the government and the Saudi-led coalition to proceed to Houthi-controlled Hudaydah port reaches the proportions of a small flotilla. Combined, these images would seem to tell a simple and compelling story: the Saudi-led coalition and Yemeni government are preventing fuel from entering Hudaydah to spite the Houthis, and ordinary Yemenis are paying the cost.

Yet the reality is much murkier. The truth is that the government and the Houthis are both guilty of participating in a self-interested tug of war to control fuel imports through Hudaydah, with little concern for the human cost of the disruption. This time around the Yemeni government, supported by the coalition, suspended approvals for fuel imports to dock and unload at Hudaydah throughout June. The Houthis, meanwhile, exploited the halt in fuel imports for political propaganda purposes and economic gain. By framing the fuel crisis as a symptom of foreign aggression that is exacerbating an already dire humanitarian situation, the group attempted to absolve itself of any responsibility while cynically controlling the supply of fuel to market, driving up prices, and, by extension, Houthi revenues.

Origins of the Latest Fuel Standoff

Currently, all fuel import shipments headed to Houthi-controlled Hudaydah port must pass through the United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism (UNVIM) in Djibouti. Once cleared, they then proceed to the CHA for a security check by the Saudi-led coalition. Before receiving authorization to proceed to Hudaydah port, vessels must receive final approval from the government’s Technical Office of the Supreme Economic Council, which checks that importers have submitted the necessary paperwork, in accordance with government fuel import regulations. In June, however, the Yemeni government suspended permission for fuel tankers to exit the CHA and dock at Hudaydah port. The last fuel shipment to arrive at the port prior to this was aboard the Alejandrina on May 31, carrying 8,400 metric tons (MT) of fuel oil. As of June 30, a total of 20 vessels carrying a combined 500,000 MT of fuel were in the CHA.[1]

The Yemeni government made the move after becoming suspicious that the Houthis had withdrawn up to 45 billion Yemeni rials (YR) from a ‘special account’ at the Central Bank of Yemen’s (CBY) Hudaydah branch, and misappropriated the funds by channeling them to the group’s war effort.[2] The account contained months of fuel import taxes and customs fees which, per an agreement that the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen (OSESGY) brokered in November 2019 between the Houthis and the government, would be earmarked to pay public sector employees in Houthi-controlled areas.[3] The mechanism was essentially a scaled-down version of an unrealized aspect of the Stockholm Agreement, in which the parties had agreed that revenues from Hudaydah, Saleef and Ras Issa ports would be deposited at CBY Hudaydah and used toward the payment of public sector salaries.[4]

The November fuel import mechanism was intended to prevent future disruptions to fuel imports entering through Hudaydah, which then get distributed in Houthi-controlled territories, following multiple fuel crises in 2019.[5] In March and April last year, there was a significant buildup of vessels in the CHA and a disruption to the domestic fuel market after the Houthis allegedly urged importers not to comply with the government’s Decree 75, which outlined regulations that must be met for obtaining permission to import fuel into Yemen. Traders who wished to import via Hudaydah port already had to obtain authorization from the Houthi-run Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) and agree to hand over the fuel to the YPC, the sole authorized fuel distributor in Houthi-controlled territory. As a sweetener, the Houthis offered to cover demurrage costs for vessels delayed from docking at the port, according to several fuel traders who spoke with the Sana’a Center at the time. The same standoff played out again in September last year, this time in reaction to the government’s Decree 49, which obligated all fuel importers to pay fuel import taxes and customs to the government in order to import fuel into Yemen, in addition to allowing for fuel quality control checks.

Funds in the CBY Hudaydah special account were supposed to be left untouched until the two sides agreed upon the list of public sector employees to be paid and which side would make up any difference in the amount needed to cover the salary payments. On April 16, the Houthi-run Supreme Economic Committee issued a statement saying that the OSESGY mechanism had expired and that it would use revenues accumulated up until March 31 to unilaterally start paying an undisclosed number of public sector employees in Houthi-controlled territories half salaries, though as of the end of June there was little indication that these payments had been made.[6]

Evidence that the funds were withdrawn and used for Houthi military campaigns is circumstantial. According to government officials, per the terms of the November 2019 agreement, the Houthis agreed to provide regular bank statements to OSESGY, which would then be conveyed to the Yemeni government, proving that the fuel and tax customs revenues remained in the CBY Hudaydah special account.[7] Government officials told the Sana’a Center that they have not seen any bank statements since early February, speculating that the Houthis withdrew the funds to help finance the group’s military campaign and the territorial gains made in 2020.[8]

OSESGY has tried to kickstart talks over a reconfigured version of the fuel import mechanism but the government has been reluctant to enter discussions until the Houthis confirm or return the YR45 billion to the special account.[9] Government officials also told the Sana’a Center that it may again attempt to implement Decree 49, requiring fuel import taxes and customs fees be paid directly to the government rather than deposited in the special account at CBY Hudaydah, with the revenue to then be used to pay public sector employees in Houthi-controlled territory.[10] The government attempted a similar move in August last year, leading to a standoff the following month in which the government eventually backed down.

It is unclear how the same approach from the government would prove any more successful now. Importers will still need authorization from the Houthi-run YPC to enter and unload at Hudaydah port, and the Houthi authorities having demonstrated their willingness to hold up fuel deliveries and risk shortages to thwart the Yemeni government’s attempts to regulate fuel imports. The YPC’s leverage is rooted in the fact that Houthi-controlled territory, where the majority of Yemen’s population lives, represents the country’s biggest domestic fuel market where the most profit can be made.

While suspending imports through Hudaydah in June 2020, the government granted approval for fuel traders to import fuel via Mukalla instead. From Mukalla port, the fuel is trucked overland to Houthi-controlled territory, a substitute trade and supply route used during past disruptions to fuel imports via Hudaydah. The government also sanctioned additional fuel imports via Aden port.

Never Let a Good Crisis Go to Waste

In the run-up to and immediately after the arrival of the last fuel shipment to Hudaydah in May, the Houthis started to sound the alarm on acute fuel shortages in their areas.[11] They warned that the suspension of import activity and accompanying fuel shortages harmed the group’s ability to combat the spread of COVID-19 in Yemen. In a June 6 letter to United Nations Resident Coordinator for Yemen Lise Grande, the Houthis argued that blocking fuel tankers from entering Hudaydah had a considerable negative impact on the humanitarian situation in Yemen, with the lack of fuel directly affecting hospitals, and health, hygiene and water sectors in general. This argument was echoed in a Houthi-run YPC circular on June 9.[12]

Houthi authorities’ statements on the ramifications of acute shortages are worrying, given the scale of Yemen’s humanitarian and economic crises. External actors like the UN and international humanitarian organizations have a duty of care that shapes a collective effort to protect the population at large as much as possible. Prolonged fuel shortages in northern Yemen have significant humanitarian implications, including on the implementation of humanitarian operations and the transportation of food and water, given how fuel prices are a major contributing factor behind the rise in food prices during the conflict.[13]

During June, long lines formed outside fuel stations in Houthi-controlled territories.[14] While the image of vehicles queuing up in Houthi territories implies one story, import data tells a different one, bringing into question the speed at which the fuel crisis escalated. The temporary suspension of fuel imports into Hudaydah on a number of occasions aside, fuel has continued to flow fairly consistently through the port.[15] Over the 12-month-period from June 2019 until May 2020, fuel imports into Hudaydah averaged 195,000 MT.[16] In January and February, imports amounted to 170,000 and 188,000 MT, respectively, with imports then jumping in March, April and May, to an estimated 237,000, 228,000 and 190,000 MT of fuel, respectively.[17] The March 2020 figure represented a record monthly high arriving at Hudaydah port since the conflict began.[18] This suggests that there may have been a surplus of fuel created in Houthi-controlled areas before the group issued the first shortage warnings in June.

The high fuel import levels in March and April coincided with a drop in global prices.[19] March prices fell further in April, with Brent Crude and WTI Crude plummeting to $26 and $11 dollars per barrel respectively.[20] According to Yemeni fuel traders, the time between an importer securing a fuel shipment from the United Arab Emirates, where a significant amount of fuel entering Hudaydah (and Yemen as a whole) comes from, and the vessel arriving at Hudaydah port is typically between 15 and 30 days, with the longer wait time often due to bureaucratic delays.[21] Given this timeline, fuel arriving in late March through May was likely bought on the cheap, with the Houthi-run YPC banking on a windfall.

This bet looked to have backfired, however, as the drop in global fuel prices coincided with a drop in global demand.[22] In Yemen, although incredibly difficult to accurately gauge, indicators suggest that demand also notably decreased from March onwards, a view shared by fuel traders who spoke with the Sana’a Center.[23] This was linked to decreased mobility among sections of the population fearful of contracting COVID-19 as well as the decline in remittance flows from migrant workers in neighboring countries, namely Saudi Arabia, which has forced Yemenis to deal with reduced incomes and cut back on spending.[24]

With a surge in fuel imports being met with a drop in demand, the Houthi-run YPC likely inadvertently clogged its own distribution pipeline. To avoid losing money as a result of the situation, the Houthis needed an increase in fuel prices.

Fuel Rationing and Higher Prices Leads to More Revenues for the Houthis

The government’s decision to suspend fuel imports appears to have thrown the Houthis a lifeline on their bet on importing cheap fuel, allowing the group to create the public perception of shortages and justify fuel rationing, in turn increasing market prices and allowing the group to recoup more revenues. The Houthi-run YPC instituted a quota system on June 10, with strict time restrictions dictating what times citizens can queue up and purchase up to 40 liters of fuel based on their vehicle registration number, creating a sense of urgency and scarcity.[25] The system was brought in before there were more obvious signs to suggest increased shortages. Three-day long queues were reported in Hudaydah during the third week of June, with [26] The fuel price hikes that occurred in Houthi-controlled territories parallel to the buildup of vessels in the CHA also presumably helped the Houthi-run YPC to cover rising demurrage costs.

Evidence for the Houthi objective of limiting the overall amount of fuel available for purchase is also bolstered by the fact that fuel trucks were being denied entry into Houthi-controlled territory. During a June 20 televised telephone interview with Houthi-run YPC spokesperson Ameen al-Shubaiti, Yemeni journalist Abdulhafidh Mougeb asked Al-Shubaiti about why the YPC was restricting the movement of fuel trucks. Mougeb cited up to 60 trucks held in Al-Jawf, 1oo trucks in Affar, Al-Bayda, 50 trucks in Taiz and 50 trucks in Hudaydah. Using the reported figures that Moujeb presented to the Houthi-run YPC spokesperson, the 260 trucks would be carrying more than 50,000 barrels of fuel. On June 26, an estimated 44 fuel trucks were shown in a video circulated on social media idling outside the group’s territory in an area close to the borders between Al-Jawf, Marib and Sana’a governorates.[27] Per local sources the Sana’a Center spoke with, the trucks in Taiz were stopped near Al-Rahidah. In Hudaydah, trucks were being forced to idle near Houthi-held Bayt al-Faqih.[28]

On June 22, the government accused the Houthis of denying more than 150 fuel trucks entry into Houthi-controlled territories and threatening truck drivers and fuel traders.[29] It also denounced such actions as a clear illustration of the Houthis’ rejection of government attempts to lessen the impact of the disruption to Hudaydah fuel imports on the broader population.[30]

While it is notable that the Houthis did not precipitate this current standoff over fuel imports, their actions appear to be taken from a playbook they developed during past episodes: shortages are accompanied by price hikes and well-coordinated advocacy campaigns aimed at the UN and other international actors.[31]

During the September 2019 standoff, the price of fuel in Sana’a climbed to YR20,000 per 20 liters from YR7,300 the previous month, a 239 percent increase.[32] The four preceding months saw a spike in fuel import activity, with 800,000 MT coming in via Hudaydah, compared to 630,000 MT [33] The import data raises the possibility that the Houthis stockpiled fuel in anticipation for a planned disruption. The supply of Marib Light crude produced at Block-18 in Marib and refined locally is another factor that helps the Houthis to mitigate the impact of any disruption to Hudaydah fuel imports.

When prices went up in September 2019 during the onset of the standoff, Houthi authorities increasingly lobbied UN agencies, INGOs and humanitarian organizations to put pressure on the government and the Saudi-led coalition to allow fuel to enter Hudaydah, with the larger objective likely being to get the government to back down from implementing Decree 75 and Decree 49.[34] The strategy paid off. At the beginning of October 2019, the government and the coalition issued a waiver to a number of vessels that were allowed to proceed from the CHA to Hudaydah.[35] OSESGY mediation efforts also paved the way for the Hudaydah fuel import mechanism that was agreed in November, a catalyst of the current standoff.

Without Accountability, the Next Fuel Crisis Awaits

The ongoing saga over fuel imports in Yemen represents one front in the warring parties’ reckless economic warfare, which has had an immensely destabilizing effect on the country’s economy and served to exacerbate the humanitarian situation.

The government’s Decree 75 and Decree 49, while ostensibly fuel import regulations, are in the current context weaponized in support of the government’s greater war aims. The Houthi authorities’ response has similarly arisen to protect financial and political dimensions of the group’s wider military pursuits. The mandate of UN agencies, INGOs and aid organizations prioritizes immediate humanitarian need for fuel, but the lobbying of the Yemeni government and the Saudi-led coalition to release fuel tankers held in the CHO has essentially aided the Houthi side in the fuel standoff.

At the same time, international organizations have not called out the Houthi authorities for the latter’s role in stage managing and profiteering from fuel crises in northern areas. According to one fuel trader who spoke with the Sana’a Center, the Houthis have warned importers against sailing their tankers out of the CHA or seeking to break their contracts with the YPC and sell the fuel elsewhere. The Houthi authorities backed up these warnings with threats to deny importers future permission to distribute fuel in Yemen’s northern areas, the country’s most lucrative market.[36]

The longer such standoffs persist and are framed as the cause of a fuel crisis in Houthi-control areas, the higher the likelihood the UN and international pressure will again come to bear on the Yemeni government and the coalition to stand down, again undermining the government’s attempts to assert authority over fuel imports. This appears to be playing out again.

On July 2, the Technical Office of the Supreme Economic Council announced that it would award import licenses to four shipments carrying a total of 92,000 MT tons of various fuels to Hudaydah: one carrying 29,000 MT of petrol, one with 28,000 MT of diesel, another carrying 27,000 MT of mazout, and one vessel carrying 8,000 MT of liquified petroleum gas (LPG).[37] The government authorized the deliveries in response to a request made by the UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths, who met with government officials in Riyadh on June 30.[38] Thirteen out of the 20 vessels idling during June, carrying a combined total of 338,000 MT, had submitted fuel import applications to the OSESGY in June to be passed on for approval to the government-run Technical Office. The four vessels that the government authorized to proceed to Hudaydah Port were among the applications submitted.

While a deesclation of the standoff is a positive outcome for Yemenis at large, a resolution without accountability placed on both sides for their roles in the disruption and the stage-managed fuel shortage almost certainly ensures that Yemen’s next fuel crisis is just around the corner.

Timeline of the Tussle Over Fuel Imports

- July 2018: Houthi authorities reinstate Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) as the sole, authorized distributor in Houthi-controlled areas. Fuel traders that wish to import via Hudaydah port must obtain authorization from the Houthi-run YPC and agree to handover the fuel to YPC upon entry.

- August 2018: President Hadi announces the establishment of the Economic Committee.

- September 2018: The Yemeni government announces Decree 75, outlining specific regulations that fuel importers must meet in order to obtain government permission to import fuel to Yemen, the most important being to provide documentation that shows that importers intend on paying the exporter using the formal banking system.

- October 2018: The government begins implementing Decree 75 through the Technical Office of the Economic Committee, responsible for assessing fuel import applications and their adherence to Decree 75 regulations.

- December 2018: The government and the Houthis sign the Stockholm Agreement. As part of the deal the two sides agree that revenues from Hudaydah, Saleef, and Ras Issa ports are to be deposited in the Hudaydah branch of the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) and used to pay local public sector employee salaries.

-

March – April 2019:

- Houthis allegedly urge fuel importers not to submit applications to the Technical Office of the Economic Committee or adhere with Decree 75.

- Government doesn’t allow fuel tankers to advance from the Coalition Holding Area (CHA). The Houthis offer to cover fuel importers’ rising demurrage costs due to delays before docking.

- Reduced fuel import activity at Hudaydah port ensues, followed by reports of fuel shortages and price hikes in Houthi-controlled territory.

- Houthi-run YPC lobbies the Office of the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen (OSESGY_ and other UN agencies to intervene and facilitate the entry of fuel; daily demonstrations are staged outside a UN compound in Sana’a.

- Fuel standoff fissles out after an increase in supply of fuel to local markets in Houthi-controlled areas.

- June 2019: The government orders a blanket ban on any fuel shipments arriving from Al-Hamriya port in Sharjah, UAE, or any port in Iraq or Oman.

- July 2019: Government issues Decree 49, making it obligatory for all fuel importers to pay fuel import taxes and customs to the government in order to import into Yemen, in addition to allowing for fuel quality control checks.

- August 2019: The government starts implementing Decree 49, although it faces difficulties at Hudaydah port, with fuel importers reluctant to adhere to the new regulations.

-

September 2019:

- Hudaydah witnesses a significant reduction in fuel import activity following a build-up of vessels in the CHA.

- Fuel shortages are reported in Houthi-controlled areas, where the price of fuel rises from 7,300 in August to 20,000 Yemeni rials per 20 liters.

- Houthi authorities increase lobbying efforts with UN agencies, INGOs, and humanitarian actors, which intercede with the government in an attempt to break fuel impasse.

- October 2019: Mediation by the OSESGY leads the government to allow a limited number of fuel deliveries to Houthi-controlled ports.

- November 2019: OSESGY brokers the establishment of a Hudaydah fuel import/Decree 49 mechanism, requiring fuel importers to deposit fuel import taxes and customs into the CBY’s Hudaydah branch. In keeping with the Stockholm Agreement, the agreement in principle is for the money to be used to help cover public sector salary payments in northern, Houthi-controlled areas.

- February 2020: Government receives the last bank statement concerning funds deposited in the special account at CBY Hudaydah.

-

March-May 2020:

- Houthi-run YPC receives increased amounts of fuel via Hudaydah: from 188,000 MT in February to 237,000 MT in March; 228,000 MT in April; and 190,000 MT in May.

- On April 16, the Houthis announce that they had withdrawn funds previously deposited in the special account up until March 31, 2020.

-

June 2020:

- The Yemeni government orders the suspension of fuel imports to Hudaydah port in what it says is a response to the Houthis’ withdrawal of funds from the CBY Hudaydah special account.

- Houthi-controlled areas see reduced supplies of fuel on the local market coupled with fuel price hikes – in Hudaydah, the price of fuel oil jumps from 5,000 to 17,000 Yemeni rials per 20 liters.

- As of June 30, 2020, 20 fuel vessels are idling in the CHA, carrying an estimated combined total of 500,000 MT of fuel.

- July 2020: On July 2, the government relents on the total suspension and the Technical Office of the Supreme Economic Council awards import licenses for four shipments, carrying: (1) 29,134 MT of petrol; (2) 27,502 MT of diesel; (3) 26,953 MT of mazout; and (4) 8,315 MT of liquified petroleum gas (LPG).

This economic bulletin appeared in Struggle for the South – The Yemen Review, June 2020

The Yemen Economic Bulletin by the Sana’a Center serves as Yemen’s go-to economic newsletter, providing detailed analysis, commentaries, reactions and actionable recommendations.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover diplomatic, political, social, economic and security-related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Endnotes

- Data from MarineTraffic, June 2020, https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/home/centerx:43.6/centery:17.2/zoom:7

- Sana’a Center interviews with government and UN officials in May and June 2020; Supreme Economic Council statement published via Economic Committee Facebook page, June 11, 2020, https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=596212821007976&id=272799003349361

- Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, “War’s Elusive End – The Yemen Annual Review 2019,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, January 30, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/8923#UN-Steps-In-to-Coordinate-Port-Access-Issues-but-Revenue-Dispute-Remains.

- Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, “Starvation, Diplomacy and Ruthless Friends: The Yemen Annual Review 2018,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, January 22, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/6808#DCM-The-Stockholm-Agreement.

- Ibid.

- Yemeni Press Agency, “Important Statement from the Supreme Economic Committee Regarding the Payment of Salaries of State Employees,” Yemeni Press Agency, April 16, 2020, http://www.ypagency.net/252865

- Sana’a Center interviews with government officials in May and June 2020.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Sana’a Center interviews with UN officials in May and June 2020; pro-Houthi Telegram channels, June 2020.

- Per copies of the letter to Lise Grande and the circular issues by the Houthi-run YPC obtained by the Sana’a Center in June 2020; Houthi-run Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) Facebook, June 9, 2020, https://facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=3392298864114660&id=321250264552884

- Norweigan Refugee Council (NRC), “Looming Fuel Crisis is Threatening Food, Hospitals and Water,” Norweigan Refugee Council (NRC), June 25, 2020, https://www.nrc.no/perspectives/2020/looming-fuel-crisis-is-threatening-food-hospitals-and-water/

- Ibid; Sana’a Center interviews with residents in Hudaydah and Sana’a in June 2020.

- Per fuel import data obtained and verified by the Sana’a Center in June 2020. These figures differ from UN commodity tracking data due to differences in calculation methods. Import data the Sana’a Center has used is based on the dates on which fuel tankers berth at Red Sea ports, whereas UNVIM import data is based on the dates on which ships sail from the ports, so there can be variations between the two sets.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Sana’a Center interviews with three Yemeni fuel traders on June 25, 2020.

- Alex Longley, Javier Blas, and Jacqueline Davalos, “Oil’s 24% Plunge in a Day Signals No End in Sight for Meltdown,” Bloomberg, March 18, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-17/oil-extends-slump-as-virus-spread-threatens-global-recession; Tsvetana Paraskova, “U.S. Oil Prices Fall To $11 Per Barrel In Historic Crash,” Oilprice.com, April 20, 2020, https://oilprice.com/Energy/Oil-Prices/US-Oil-Prices-Fall-To-11-Per-Barrel-In-Historic-Crash.html.

- Sana’a Center interviews with three Yemeni fuel traders on June 25 and 30, and July 1, 2020.

- Sana’a Center interviews with three Yemeni fuel traders on June 25, 2020.

- Sana’a Center interviews with three Yemeni fuel traders on June 25 and 30, and July 1, 2020.

- Iona Craig, “In Yemen, Families Suffer as COVID-19 Dries up Money from Abroad,” The New Humanitarian, June 16, 2020, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2020/06/16/Coronavirus-Yemen-economy-remittances.

- Houthi-run Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) Facebook Page, June 09, 2020, https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=3392298864114660&id=321250264552884

- Sana’a Center interviews with a Yemen fuel market expert and Hudaydah resident on June 22, 2020.

- Mohammed al-Dhabyani (@maldhabyani), June 27, 2020, https://twitter.com/maldhabyani/status/1276628720829136896.

- Sana’a Center interviews with local sources in Yemen and a Yemen fuel expert on July 3 and 5, 2020.

- Economic Committee Facebook Page, June 22, 2020, https://facebook.com/economiccommittee/photos/a.273096309986297/602568340372424/?type=3&source=57

- Ibid.

- Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, “War’s Elusive End – The Yemen Annual Review 2019,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, January 30, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/8923#New-Rules-a-New-Ban-and-a-New-Crisis

- Ibid.

- Per fuel import data obtained and verified by the Sana’a Center in June 2020.

- Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, “War’s Elusive End – The Yemen Annual Review 2019,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, January 30, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/8923#New-Rules-a-New-Ban-and-a-New-Crisis

- Ibid.

- Sana’a Center interview with a Yemeni fuel trader on June 30, 2020.

- Supreme Economic Council statement published via Economic Committee Facebook page, July 02, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/272799003349361/posts/608741089755149/

- Supreme Economic Council Twitter account, July 20, 2020, https://twitter.com/SECYemen1/status/1278767122727010310; OSESGY Twitter account, June 30, https://twitter.com/OSE_Yemen/status/1277966722209705991