Executive Summary

Executive Summary

Five years of war in Yemen have weakened local authorities’ ability to fulfil their roles in economic, social and cultural development and their financial and administrative capacity to provide basic services such as healthcare, education, electricity, water and sanitation.

This paper gives an overview of wartime challenges faced by local authorities in Shabwa governorate, in southern Yemen. It provides an overview of administrative, financial and security challenges, such as corrupt hiring practices, tribal vendettas, weak rule of law and diminishing financial resources, and proposes recommendations to address these challenges.

Insights shared at forums for the Shabwa Strategic Group, which brings together local authority officials, academics and civil society representatives, are incorporated in this paper, which also draws on interviews conducted with local authority officials.

Introduction

Local governance in Yemen is based on the Local Authorities Law, Law No. 4 of 2000, and its amendments in Law No. 18 of 2008.[1] The Local Authorities Law emerged in response to demands for decentralization and local autonomy, which grew after the short-lived civil war between north and south Yemen in 1994. In 1998, the Yemeni government divided the country into 21 official governorates,[2] each of which was divided into districts. Governors and district directors were appointed by the government in Sana’a, centralizing authority in the capital with no local representation in local authorities.[3] The appointment of “outsiders” to run local authorities, who often had no connection to the area, increased tension and calls for federation and, in the south, secession.[4]

The Local Authorities Law of 2000 was issued to assuage these calls by giving governorates and districts more autonomy and space to manage their own affairs. The law provided for local elections to select council representatives, and outlined the structure of local authorities, their roles and responsibilities. Local elections were held in 2001 and 2006, but all elections since then were postponed due to the prevailing security situation.

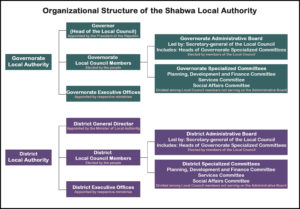

Local governance operates at two levels: governorate and district. The following chart shows key administrative structures of local authorities at district and governorate levels:

According to the Local Authorities Law, district-level local councils are responsible for drafting plans which are reviewed by the executive offices of ministries in the governorate and submitted to the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation for inclusion in the investment program of the governorate. Once approved, executive offices and local councils oversee the implementation of these plans. The governor’s office, the local offices of the Finance Ministry and the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, and the directors of local councils are responsible for reviewing and discussing local finances, including developing and collecting local revenues.

These functions have been weakened since 2011 due to instability across Yemen after the Yemeni uprising, the takeover of Sana’a by the armed Houthi movement in 2014 and the intervention of the Saudi-led military coalition in 2015. The ongoing conflict has led to the fragmentation of the central government, the collapse of investment support and other central revenues and a decline in local revenues, all of which have diminished the capacity of local authorities. The conflicting interests of the warring parties and the weakening of the rule of law have diminished the role of local councils.

This paper provides an overview of how war-time challenges have affected local governance in Shabwa governorate. It benefits from the visions, ideas and insight shared by local officials, academics and civil society representatives at forums for the Shabwa Strategic Groups held in Addis Ababa in December 2019 and February 2020, and consultative meetings of the Shabwa Strategic Group in Ataq, Shabwa, in March 2020. The author also conducted interviews with local authority officials, academics and activists in Shabwa in March 2020.

Shabwa Governorate: Snapshot

Shabwa is a strategically positioned governorate in central south Yemen, bordering the governorates of Hadramawt, Abyan, Marib and Al-Bayda. Rich in oil, Shabwa produced almost 10 million barrels of oil in 2011.[5] Its 280-kilometer coastline on the Arabian sea supports a thriving artisanal fishery, while several important economic facilities line the coast, such as the Al-Nashmiah Port, through which oil from Shabwa and Marib is exported, and the Balhaf facility, through which gas from Marib is exported, as well as the Qana Historical Port and various fishing sites.

Shabwa’s location and resources have made it a strategic concern for the warring parties during the conflict. For example, forces loyal to the internationally recognized Yemeni government positioned in Marib must pass through Shabwa to reach Abyan, Aden and Hadramawt. Financial support from the central government to Shabwa ceased in 2015, however with the exception of salary payments. Local authorities have since tried to cover this deficit by funding some services from oil revenue in the governorate. Despite these efforts, basic services in Shabwa are insufficient, in part due to the lack of funds and support from the central government. In the field of education, for example, the construction of new schools and educational facilities and the recruitment of new teachers have been suspended since 2011 following the Yemeni uprising and ensuing political crisis. In the 2019/2020 school year, there were nearly 195,000 students in Shabwa but just 609 schools and 5,220 teachers — a ratio of one teacher per 37 students.[6] Yemen’s relatively high birth rate[7] means the number of students entering the education system each year is outpacing the number graduating out, leading to constantly increasing overall numbers. Some 20,000 students entered first grade in the past academic year, a figure that includes children of the more than 4,250 displaced families who have arrived in Shabwa.[8] Meanwhile in the healthcare sector, no new facilities have been built during the war. There are currently 2,419 healthcare employees in Shabwa; the workforce has not grown since 2012, despite increased demand.[9]

Wartime Challenges

Local authorities in Shabwa have faced a range of challenges during the war, relating to security, administration, finances and oil production. An overview of these challenges is presented below:

Political and Security Challenges

Multiple political, military and security forces are present in Shabwa, including the internationally recognized Yemeni government and its associated political parties, and various southern entities such as the Southern Transitional Council (STC) and the Hirak movement. Conflicts between these parties — primarily between the Yemeni government and STC-allied forces — have affected the work of the local authorities and hindered their ability to provide services. Military and security groups present in Shabwa include the Yemeni army, military police, General Security Forces, Special Security Forces, Shabwa Elite Forces, the Southern Resistance, among others. There is a general lack of coordination between these entities and frequent clashes.

Shabwa is a tribal area, and tribal conflicts and vendettas have disrupted service provision in the governorate since long before the conflict. Tribal disputes have delayed local projects for more than 10 years in some cases, often due to disputes over land. For example, tribes near Al-Rawdah city prevented a sanitation project to treat wastewater for use in agricultural irrigation because they objected to the placement of drains. Due to this, untreated sewage remains a problem in the city. Tribal disputes have also disrupted local services.

The issue has been compounded during the conflict by problems in the judiciary: amid weak rule of law and slow judicial processes, small disputes have escalated into major confrontations, leading to the intervention of tribes. Shortages in judicial staff in Shabwa have led to long delays in court hearings and resolutions of cases. There are 15 courts in Shabwa with only one judge appointed for every three courts, in violation of judicial regulations which state that there must be at least one judge in every court.[10] Under the regime of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, the number of southern students graduating from the Higher Institute of the Judiciary was disproportionately low, in what has been viewed as part of a deliberate policy to reduce the influence and capacity of the south.[11] Prior to 2011, most judges in southern courts were from northern Yemen; during the war, judges from the north have refused appointments in southern governorates.

Administrative Challenges

Local authorities in Shabwa face multiple administrative challenges, some of which are national issues which predate the conflict. Corrupt recruitment practices are a key challenge in the governorate.

Since 2011, partisan loyalties have been a driving force in local authority appointments; this has worsened during the conflict. Political considerations, rather than formal hiring processes for public office, have guided employment in local government, often to senior management positions. Recruitment for management and leadership level jobs in local government is sometimes based on political connections rather than a candidate’s qualifications or the criteria for promotion in the public sector. In Shabwa, the practice by political parties of ensuring appointments for their supporters has reached the highest positions in the governorate. There is a lack of accountability in instances of neglect of duties or weak performance, and at most individuals may be removed from their position. Other issues include the practice of public offices being inherited. Meanwhile, some government departments in Shabwa are overstaffed because they employ large numbers of people who receive salaries but do not work, and who are gifted positions for political reasons rather than because of staffing needs.

During the war, many procedures stipulated in the Local Authorities Law and other laws pertaining to employment have not been followed. For example, the law stipulates that certain administrative positions be appointed by the prime minister, but this legal framework is no longer consistently followed. Many of the functions of district-level executive offices have been suspended during the war, and there is no development plan for the governorate or budget from the central government. Executive offices should be responsible for defining local needs and drafting plans, but during the war many projects have been implemented by the direct decision of the governor’s office, without being submitted to elected local council members. In addition, local authorities have been unable to collect revenues stipulated in the Local Authorities Law. This has led to the marginalization of local councils that have been unable to fulfil their functions.

International organizations, which are required to coordinate their work with the governorate branch of the Ministry for Planning and International Cooperation, have implemented projects during the war without coordination with this office. This has resulted in organizations duplicating each other’s work in some districts while neglecting other districts, and overlap between projects by different organizations. The governor has issued directives that no activities by international organizations may be approved by local authority departments without coordination with the Planning and International Cooperation office, but multiple projects in fields including healthcare, education, water and agriculture have been implemented without any such prior coordination.

Oil and Gas Production Challenges

Oil production in Shabwa has decreased during the war, from close to 15.84 million barrels in 2014 to less than 4.35 million barrels in 2019.[12] Prior to the war, oil from Shabwa accounted for 29 percent of Yemen’s total oil output; this dropped to 21 percent by 2019. Just two of Shabwa’s oil blocks — Block 2S Ak Aqlah and Block 4 — are currently operational. The decrease in oil production led to a drop in the governorate’s 20 percent share of oil revenues allocated to the governorate in 2018. In addition, the government has not deposited this revenue on a regular basis.

As well as losses in oil revenue, the suspension of work in Shabwa by some oil companies has led to losses of sustainable development revenue provided by oil companies to oil-producing governorates. The level of this contribution is determined in agreements signed between each oil company and the government and depends on the size of the company and its potential. For example, the Austrian oil and gas company OMV allocated US$400,000 for sustainable development to Shabwa in 2020, but this was reduced to US$200,000 due to collapsing oil prices during the COVID-19 pandemic.[13] Prior to the conflict, OMV contributed US$500,000 to US$600,000 annually to sustainable development in Shabwa and provided 20 educational grants to students in Shabwa. Likewise, the contribution of other oil companies to sustainable development in Shabwa has dropped during the conflict.

The National Dialogue Conference stipulated that 50 percent of the labor force of oil companies should be hired locally, but this has not been implemented. Local recruitment in Shabwa varies between 20 percent and 30 percent among different oil companies, and does not meet local employment needs.[14] Some 217 students have graduated from Shabwa’s Oil and Mineral College since 2018 but a very limited number have been employed by oil companies. Insufficient local employment has created conflicts between local communities and oil companies, increasing pressure on local authorities. The local offices of oil companies are in Sana’a; no oil companies have offices in Shabwa’s capital, Ataq, and this hinders coordination with local authorities.

Meanwhile, Shabwa receives no share in the revenue from the Balhaf LNG station. Prior to the war, local authorities benefited from sustainable development revenue from this facility, but this stopped when the facility stopped operating in 2014.

Financial Challenges

The war has created multiple financial challenges for local authorities, primarily a lack of financial resources. At the end of March 2020, Shabwa’s financial resources for 2020 stood at about 618.5 million Yemeni rials (YR), of which YR530.488 million was rolled over from 2019. Covering Shabwa’s annual local needs, according to the 2020 local investment plan — which, like those for all governorates, has not been able to be changed since 2014 — requires YR1.465 billion.[15]

Support from the central government to finance capital investments in Shabwa stopped in 2015 while civil servant salary payments ended in August 2016,[16] and as a result local authorities have struggled to provide basic services in most districts. Joint public revenues collected in Shabwa, such as the government share of telecommunications revenue, are sent to the central government and are then meant to be redistributed among the governorates; these are not being provided to governorates during the war. Shabwa also has suffered from a low level of public revenue collection, such as taxes, and revenues collected by some departments are not deposited in the assigned accounts in the Central Bank of Yemen branch in Shabwa.

Local authorities also suffer from financial waste and corruption. The performance of the financial oversight and inspection department has been weak, and there is no internal review. Furthermore, contracting procedures in some governmental projects are processed outside the Tender Committee.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are offered to address the challenges outlined above and to boost the capacity of local authorities in Shabwa.

-

Security and rule of law in Shabwa can be fostered by ensuring that every court has a judge, in line with judicial regulations.

- Judges from Shabwa who are assigned to other governorates should be transferred to Shabwa through coordination with the judicial council.

- Qualified cadres from Shabwa should be given the opportunity to study at the Higher Institute of the Judiciary.

-

Tribal conflicts should be addressed so they do not undermine service provision in the governorate.

- The general security forces should swiftly enforce the law in criminal cases.

- A reconciliation committee should be formed in the governorate to resolve disputes and vendettas.

- To improve administration of local authorities, recruitment processes for public office must abide by regulations.

-

The role of local authorities should be strengthened by activating their responsibilities under the Local Authorities Law and other relevant laws.

- District-level local authorities should identify local needs and priorities and draft plans.

- Contractors should be selected through Tender Committees to ensure the most qualified and cost-efficient contractor or supplier is hired.

- Local councils should be involved in approving the investment budget of the governorate.

-

To increase oil revenue, local and central authorities should coordinate to create the environment necessary for oil companies to resume operations.

- Oil companies should increase recruitment of local staff.

- Oil companies should meet their financial commitments to contribute to sustainable development in Shabwa.

- Oil companies should open local offices in Shabwa to facilitate coordination with local authorities.

-

The financial capacity of local authorities should be improved through the following measures:

- Central authorities should restore central investment support to local authorities and ensure that joint public revenues and oil revenues allocated to local authorities are deposited regularly.

- Local authorities should ensure that local revenues are deposited in the Shabwa branch of the Central Bank of Yemen.

-

Local authorities should encourage the private sector to contribute to development in Shabwa.

- Projects should be established that exploit the raw materials available in Shabwa, for example fish canneries or projects in the agricultural or textile industries.

-

Financial oversight should be improved by activating the role of the public funds prosecutor’s office, the Central Organization for Control and Auditing, and the anti-corruption agency.

- An electronic accounting system could improve oversight.

- International organizations should coordinate with the local office of the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation to ensure that projects meet local needs and reach all districts.

This paper was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies with Oxford Research Group, as part of Reshaping the Process: Yemen program.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Oxford Research Group (ORG) is an independent organization that has been influential for nearly four decades in pioneering new, more strategic approaches to security and peacebuilding. Founded in 1982, ORG continues to pursue cutting-edge research and advocacy in the United Kingdom and abroad while managing innovative peacebuilding projects in several Middle Eastern countries.

Endnotes

- Local Authority Law (2000) available here (Arabic and English): http://constitutionnet.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/Law%202000%20local%20authorities.pdf

- Socotra became a governorate in December 2013, leading to a total of 22 governorates today.

- Adam Baron, Andrew Cummings, Tristan Salmon, Maged Al-Madhaji, “The Essential Role of Local Governance in Yemen,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, September 15, 2016, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/3770

- Ibid.

- Report by the Petroleum Marketing Committee, Office of the Ministry of Petroleum in Shabwa Governorate, 2019.

- Records of the Education Office in Shabwa governorate, 2020

- “Fertility rate, total (births per woman)”, World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?most_recent_value_desc=true

- Survey assessing IDPs in Shabwa, Khotwat Foundation for Human Development, Shabwa governorate, 2020

- Summary report on the distribution of the labor force in Shabwa governorate, Labor Force and Employment Department in the Civil Service and Insurance Office in Shabwa, 2019

- Law No. 1 of 1991 Concerning the Judiciary, https://yemen-nic.info/db/laws_ye/detail.php?ID=11295

- Syed Mustafa, “President of the Southern Judges Club in a heated conversation with Arab Yemen,” Arab Yemen, February 8, 2020, https://www.elyamnelaraby.com/457912/رئيسة-نادي-القضاة-الجنوبي-في-حوار-ناري-لـاليمن-العربي

- Report by the Petroleum Marketing Committee, Office of the Ministry of Petroleum in Shabwa Governorate

- Phone interview with OMV Corporate Social Responsibility Coordinator, April 13, 2020.

- General results of the Administration of Admission and Registration, Faculty of Oil and Minerals, University of Aden, 2017-2019.

- Reports of the accounting unit of the office of the MInistry of Finance in Shabwa, March 2020; Shabwa’s projected budget for 2020, Office of Planning and International Cooperation, Shabwa.

- Mansour Rageh, Amal Nasser and Farea Al-Muslimi, “Yemen Without a Functioning Central Bank: The Loss of Basic Economic Stabilization and Accelerating Famine”, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 6, 2016, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/55

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية