Editor’s note: The author, a Yemeni analyst based in Taiz, is writing under a pseudonym for security reasons.

Introduction

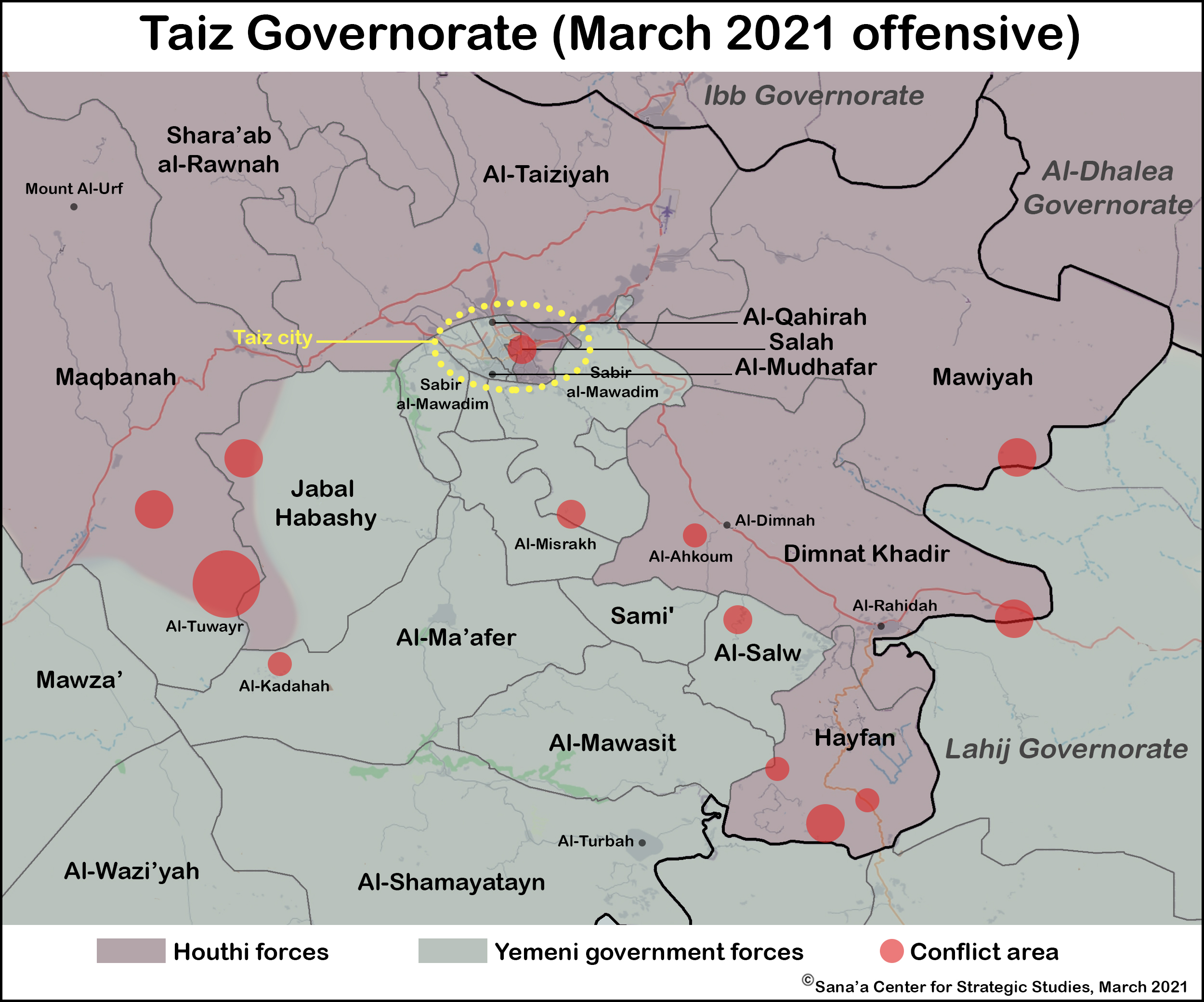

Taiz has been a divided city since 2015, with Houthi forces (Ansar Allah) holding the northern suburbs of Yemen’s third-largest city as well as much of the northern part of the governorate. The Houthis control both Taiz’s industrial zone to the northeast of the city, gaining hundreds of millions of rials every year through taxes on factory owners, as well as the governorate’s three main roads. As a result, for the past six years residents of Taiz city have lived under siege. Houthi snipers are a constant presence, making some roads and alleyways impassable. Food and supplies into government-held portions of the city are forced to make the long journey up from Aden, entering Taiz through the sole government-held road, more dirt track than paved road. A trip across town that once would have taken 15 minutes now takes 5-6 hours, as travelers are forced to navigate around frontlines and through a myriad of checkpoints held by competing militias and military units.

Efforts to lift the siege on Taiz through negotiations have failed, most notably the 2018 Stockholm Agreement, which included a statement of understanding on Taiz in which the internationally recognized government and Houthis agreed to form joint committees to discuss the issue. Underscoring the lack of progress to resolve the situation since, UN envoy Martin Griffiths reiterated that Taiz remains “besieged” in his latest briefing to the UN Security Council in April 2021, adding that the closure of key roads has inflicted terrible social and economic consequences upon local residents for years.

The conflict in Taiz has proceeded in stages. The initial conflict between the Houthis and a loose anti-Houthi coalition eventually gave way in 2018 and 2019 to a conflict within the anti-Houthi coalition. Islah and its affiliated military units largely won that war, pushing rival forces such as the 35th Armored Brigade and the Abu al-Abbas group out of Taiz city and into the countryside to the south and firmly establishing themselves as the main power broker on the government side in the city.

In early March 2021, the war in Taiz shifted yet again as pro-government forces launched an offensive on Houthi frontlines, resulting in some of the largest changes in territorial control in years around the city. The offensive was undertaken with the primary objective of forcing the Houthis to divert resources from a renewed offensive launched in February against the government stronghold of Marib.

With the Houthis focused on Marib, government forces in Taiz made some initial advances against depleted Houthi frontlines. However, despite calls on the government side to dedicate more resources to the Taiz battles and shift objectives to completely lifting the siege on the city, government forces’ early successes were short-lived. A lack of trust, weapons, and planning among the anti-Houthi coalition ultimately spelled failure for the offensive. By the end of March, pro-government forces remained in control of a number of newly seized areas, but were pushed out of most strategic locations captured earlier in the month.

This policy brief details how fighting played out in Taiz in March, the actions by pro-government and Houthi forces during the resumption of clashes and the impact of the violence on civilians. It ends by examining the potential for a renewed outbreak of violence in Taiz and offers practical recommendations to the Houthi movement, the internationally recognized government and the Saudi-led coalition on how to deescalate tensions in the city and alleviate the dire humanitarian and security situation for civilians in the governorate.

Pro-Government Forces See Early Gains before Taiz Offensive Stalls

The intensification of Houthi hostilities targeting the oil-rich city of Marib on February 7 caused a reaction in Taiz. Bands of fighters were secretly, and later publicly, sent from Taiz to support government forces battling the Houthis in Marib, according to an official from the Taiz Military Axis. This was partly due to the fact that both Taiz and Marib are dominated by Islah, the Islamist party that is one of the main stalwarts of the anti-Houthi coalition. Building political and media pressure also galvanized military action in Taiz to distract the Houthi offensive further east.

Fresh fighting in Taiz began on March 2, when government forces clashed with Houthi fighters on the eastern frontlines of the city. Over the past six years, the Houthis laid extensive minefields across eastern Taiz, extending from the Salah district to the Republican Palace Intersection and 40th Street. Along with the minefields, the mountainous terrain of Al-Salal, Sofitel and Al-Harir in eastern Taiz gives the Houthis a tactical military advantage, allowing them to hold the area with relatively few fighters. Snipers target any movement in no man’s land between the two sides – formerly urban areas that have become overgrown with greenery – as well as civilians across the frontline in government-held areas.

The next day – Wednesday, March 3 – government forces launched attacks on the western front of Taiz in the district of Jabal Habashy. Much like in eastern Taiz, the Houthis had relatively few fighters along the frontlines. Here, however, the low population density and easier terrain of mostly rural towns allowed government forces to make quick advances, establishing control of almost all of Jabal Habashy as well as the Al-Kadahah front in Al-Ma’afer district.

The unexpected and quick victories in the west impressed government officials – particularly Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar and Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed, the main politicians involved in pushing for action in Taiz – and led to a shift in objectives. On March 11, Taiz governor Nabeel Shamsan announced that instead of merely pressing the Houthis in Taiz as means of relieving pressure on Marib, the new goal of the Taiz offensive was to end the siege on the city and push Houthi forces out of the governorate. Shamsan, who has generally been seen as a weak figure locally, named himself the head of the Backup and Support Committee for the Battle for Liberation, which was established in March to mobilize resources to support the offensive. The committee, with urging from Shamsan, also attempted to more clearly coordinate the battles and define the offensive’s main objectives.

Within days, however, the offensive started to run out of steam. Government forces were disorganized and seemed unable to agree on a coherent strategy to retake Houthi positions. Many government soldiers were ordered into areas susceptible to Houthi attacks. Along the Al-Kadahah front, the battles stopped on the border with the Mawza’ district. In one major incident, a Houthi missile attack on Salaheddine School in Al-Kadahah led to the deaths of 15 soldiers. In Maqbanah district, in the western part of the governorate, the government advance stopped in the Upper Al-Tuwayr area, causing both Houthi and government forces to shift to hit-and-run tactics. In early April, the Houthis announced the deaths of several fighters in Maqbanah, including the head of security for the district, Abdulhakim al-Ashmali.

The Al-Ahkoum frontline became a defining test of the government’s capacities and the momentum of its expanded offensive and goals. Controlling Al-Ahkoum would mean gaining control of the main road between Al-Dimnah and Al-Rahidah, allowing pro-government forces to partially break the Houthi siege on Taiz city. However, government forces suffered a setback on this front after the killing of a prominent commander in the Hujariah Resistance, Abdo Noman al-Zuraiqi, commander of the First Battalion of the 4th Mountain Infantry Brigade. This sapped the morale of government fighters and recovering Al-Zuraiqi’s body became the main objective, an effort that took three days, after which fighting in Al-Ahkoum almost completely stopped.

The military operations started to gradually lose momentum, despite the large mobilization, and all eventually stopped without achieving their objectives. For instance, government forces halted before seizing important positions under Houthi control, like Mount Al-Urf, which overlooks the city of Al-Barh to the west of Taiz city. By March 28, the fighting had largely ceased except for a few skirmishes, and the Houthis had managed to reassert control of much of the territory they lost in early March.

The Anti-Houthi Coalition: Rivals One Day, Allies the Next

On the surface, the anti-Houthi coalition faces a number of challenges in its effort to push the Houthis out of Taiz and lift the siege. Most of these challenges, at heart, stem from the same issue: a lack of trust within the coalition. Saudi Arabia doesn’t trust Islah. Islah doesn’t trust the 35th Armored Brigade or the Abu al-Abbas Group, both of which it clashed with repeatedly in 2019 and 2020. Local authorities and military units don’t trust the Islah-dominated Taiz Military Axis, which in turn doesn’t trust the Saudi-led coalition.

In February, a delegation from the Taiz Military Axis presented a battle plan to the Saudi forces in Aden, according to an official in the Taiz local authority. Understanding the gravity of the fighting in Marib, the Taiz forces proposed reigniting dormant frontlines in the governorate. The Saudis responded positively in person to the proposal but later failed to follow up and provide sufficient weapons and munitions to Islah-affiliated units. According to the same official, the leadership of the Saudi-led coalition was concerned that such weapons could later be used by Islah to target rivals such as the National Resistance Forces led by Tareq Saleh, nephew of the late former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, based along the Red Sea Coast in Taiz and supported by both Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Instead, the coalition leadership in Aden told local commanders in Taiz to purchase the weapons themselves, saying Saudi Arabia would reimburse them later. Not surprisingly, local leaders in Taiz rejected this suggestion. Lack of weaponry on the government side eventually became a contributing factor in the offensive grounding to a halt.

At the same time, the anti-Houthi coalition was struggling to patch over old rivalries and demonstrate to the Saudi-led coalition that they could work together. In the offensive, pro-Islah forces needed support and assistance from the rest of the anti-Houthi coalition in Taiz, including groups it had previously clashed with. There were efforts to demonstrate unity in this regard. For instance, in Al-Kadahah frontline, forces from the pro-Islah 17th Infantry Brigade came together with the 5th Presidential Protection Brigade, led by Salafist commander Adnan Ruzaiq, and the 35th Armored Brigade. The 35th Armored Brigade has been perceived as close to the Socialist and Nasserist parties and for years enjoyed Emirati support as a counterweight to Islah in Taiz. In 2020, the Taiz Military Axis moved against the brigade, pushing it out of Taiz city and placing sympathetic commanders within its ranks. However, it is still viewed as a more disciplined and organized, and less ideological force, than many other military formations in the governorate.

Despite this effort for unity and enhanced coordination within the anti-Houthi coalition, the various pro-government armed groups generally failed to properly organize and agree on a single strategy. Lack of trust between local commanders and the Saudi-led coalition, which warily views Taiz as an Islah stronghold, hampered planning. As a result, advances and military maneuvers were often improvised. When tactics were planned in advance, they were often done so by officials without military backgrounds or intimate knowledge of the terrain, causing them to be ignored by local commanders. Thus, instead of one coordinated battle, the anti-Houthi coalition fought a series of disconnected, and ultimately fruitless, engagements, which allowed the Houthis, benefiting from more effective coordination, to move men from one flashpoint to another.

It was the same story on the financial front. Despite Shamsan’s call for donations to aid the war effort, few in Taiz trusted that the money would actually be used for its stated purpose. According to a local businessman, wealthy merchants and private donors worried that money collected by one of the various armed groups may later be used to fund intra-coalition rivalries, leading to further violence in the city.

Houthi Forces Mobilize to Defend Key Positions

As the battle lines in Taiz have hardened in recent years and the conflict has shifted to one within the anti-Houthi coalition, the Houthis have gradually withdrawn some of their fighters from Taiz, siphoning them off to more active fronts in Hudaydah and, more recently, Marib. To offset these losses, the Houthis have recruited locals in areas under their control. This often means that the Houthi fighters in Taiz are less ideologically motivated than their northern peers, even though they participate in the same “cultural” courses as all Houthi fighters. A government military source in Taiz pointed to this as a factor in government forces’ initial gains in early March. In both Al-Kadahah and Jabal Habashy, there were reports of Houthi fighters abandoning forward positions and weapons as government troops advanced.

The concern of Houthi commanders was clear during the first days of the battle, which led to a call for mobilization in the districts of Maqbanah, Hayfan, and Saber al-Mawadim. Ali Al Qirshi, the district manager of the Shar’ab al-Rawnah district, was one of the most effective Houthi recruiters. Other Houthi officials involved in recruiting for the battle include Adel Sha’lan, the security supervisor in Khadir district, Omar Awhaj in Hayfan district, and Muhammad Al Dhaybani in Al-Taiziyah district.

Houthi commanders were also quick to belittle the gains made by government forces, saying that they were not real advances and characterizing the attacks as psychological warfare meant solely to improve morale among pro-government fighters in Marib. Crucially, the Houthis also had a clear strategy to devote resourcing to defending strategic positions whose loss would threaten Houthi supply lines, which occurred in the area of Bilad Al-Wafi in Jabal Habashy district and Al-Ahkoum in Al-Hujariah area.

The Houthis maintain complete control of the districts of Al-Taiziyah, Shar’ab al-Salam, Shar’ab al-Rawnah, Mawiyah, Khadir, and Hayfan, as well as parts of Salah, Al-Salw, Maqbanah and Jabal Habashy. In most of these districts, the Houthi military presence is limited to token forces and supervisors (mushrifeen) – Houthi hardliners from outside the governorate. Houthi supervisors have more authority than district directors, and often rule the population by force. Local residents say they are required to make mandatory “donations” – either in-cash, in-kind (livestock) or a quota of fighters – to the Houthi war effort, or else risk punitive measures, including the confiscation of property, forced conscription or imprisonment.

Most of the Houthi military presence is centered on the frontlines around the city of Taiz, and on the outskirts of the city in areas in Jabal Habashy, Al-Shaqb, Dimnat Khadir and Sami’. The Houthis’ military and administrative headquarters are based in Hawban, Taiz’s industrial zone northeast of the city. The group also has a strong military presence on the border with Lahj, where its forces have regularly clashed with pro-government Southern Resistance forces in Kirsh.

The Taiz offensive, besides failing to lift the siege on Taiz city or reopen main routes into the city, also failed to achieve the goal of unsettling the Houthis and shifting their attention away from Marib city. It is clear that Taiz is not a priority for Houthi forces in the same way that Marib is; besides their focus on securing critical supply lines in Maqbanah and Hayfan, further evidence of this attitude was the fact that the Houthis did not send reinforcements from outside of Taiz to the frontlines in the governorate or attempt a large-scale counterattack against government forces.

Finally, the disappointment that has accompanied the Taiz offensive has not been limited to its military outcomes. The Taiz file has been conspicuous by its absence from recent diplomatic initiatives by the international community, given the intense focus on the ongoing battle for Marib. The response from influential actors inside Taiz has been to highlight what they perceive as the UN’s disregard toward the situation in the governorate, and to insist that the Houthis must lift the siege on Taiz city as a central element of any cease-fire plan.

The Civilians Caught in the Middle

As ever in Taiz, it was the civilian population that bore the brunt of the violence in March. As frontlines moved first one way and then back the other, civilians were forced to flee to avoid being caught in the crossfire. Independent monitors who spoke with the Sana’a Center on March 30 said they had documented 35 civilian casualties in the recent battles, including 20 children and four women. More than 30 families were forced to flee shelling in Upper Al-Tuwayr in Maqbanah district, causing a wave of IDPs to start heading toward areas in Jabal Habashy. It is expected that the number of civilian casualties will rise if the battles recommence and expand to areas with a high population density, such as eastern parts of Taiz city or smaller towns in Hayfan and Maqbanah district.

Residents of Taiz city, especially those that have returned to their homes after years of displacement, express significant fears of the resumption of wide-scale violence, particularly the indiscriminate shelling that has targeted residential neighborhoods. Price spikes are also a major concern. Already, the price of basic foodstuffs in Taiz is more than 30 percent higher than in other government-controlled areas, according to the industry and trade bureau in Taiz. This is largely due to the siege and the resulting cost of transporting goods via a single main route into the city: the precipitous Hayjat al-Abed mountain road. Houthi and pro-government armed factions control most secondary roads into the city, manning a number of checkpoints that trucks have to negotiate. The costs of bribes and payoffs are passed on to the consumer.

Conclusion

Despite the decline in combat operations, and the Houthis retaking many positions lost early in the government offensive, pro-government military commanders and political party leaders reiterate that the battle has not stopped. Instead, they depict the recent lull as an opportunity for forces to rest and for commanders to reassess the course of the previous battles to avoid making the same mistakes again.

Government forces likely have the capacity to restart the offensive, and potentially gain ground against the Houthis in Taiz, given the government’s massive advantage in terms of the number of fighters available. Lack of coordination and trust between the Saudi-led coalition and government forces, and among the various anti-Houthi forces, remains the biggest obstacle. The Saudi-led coalition and some anti-Houthi groups view Taiz as nothing more than Islah’s second stronghold, after Marib. As a result, opaque intra-government rivalries and competing agendas will continue to play a prominent role in developments in Taiz moving forward.

Ultimately, even if there is a new round of battles to lift the siege on Taiz, expectations for success on the government side are low absent the formulation of new tactics and methods for enhanced coordination, based on lessons learned from the disorganized March offensive.

Recommendations

To the Armed Houthi Movement:

- Lift the siege of Taiz city and stop exploiting the humanitarian issue as a part of military and political negotiations.

- Open the eastern crossings in Taiz city linking downtown with Al-Hawban to the northeast, and the northern crossing through 60th Street and Ghurab, to facilitate the movement of civilians and the transportation of medical supplies and food into the city.

- Remove landmines on the eastern frontlines of Taiz city, end the practice of booby-trapping civilian homes, and allow civilians to return to the homes that they were forced to leave since the beginning of the conflict.

- Halt immediately the targeting of civilian neighborhoods in Taiz city, as well as medical and educational facilities.

- End the occupation of educational and medical facilities in the western parts of Taiz, as well as the practice of recruiting child soldiers.

To Pro-Government Forces:

- Refrain from any further military action that risks making the humanitarian situation in Taiz worse.

- Adhere to principles related to the protection of civilians and property, whether they are in areas under government control or in Houthi-controlled areas.

- Restore the role of the state in institutions in the areas under government control, with a focus on not allowing non-state actors to exploit civilians under the pretext of a battle to liberate Taiz.

To the Saudi-Led Coalition:

- Assume a mediating role regarding internal conflicts among forces aligned with the internationally recognized government and not allow events in the conflict to be exploited to target certain groups for political purposes.

- Reconsider how Taiz is being viewed and move away from the shallow assessment of it as a stronghold of the Islah party, which ignores Taiz’s crucial political, economic and cultural contributions throughout Yemen’s history, as well as the aspirations of many citizens in the governorate.

- Support the government in strengthening state institutions in Taiz, and back efforts to curtail the influence of non-state armed actors.

- Allocate sufficient support to Taiz through projects, focused on alleviating the negative humanitarian impacts of the siege, funded by the Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program for Yemen.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

This publication was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies in partnership with Hala Systems Inc., as part of the Leveraging Innovative Technology for Ceasefire Monitoring, Civilian Protection and Accountability in Yemen project. It is funded by the German Federal Government, the Government of Canada and the European Union.

The recommendations expressed within this document are the personal views of the author(s) only, and do not represent the views of the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, its partner(s), or any other persons or organizations with whom the participants may be otherwise affiliated. The contents of this document can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the positions of the German Federal Government, the Government of Canada or the European Union.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية