Executive Summary

After a decade of humanitarian response and more than two decades of development aid to Yemen, it is time for aid actors to rethink internationally led responses to food insecurity and to reconsider the current concepts of famine in the country.

Researchers frame contemporary famines – known as the ‘new famines’ – as systemic failures, or as a result of crimes committed during armed conflict. This theoretical approach understands famine not just as a lack of available food or access to food, but as failures of accountability and response. By highlighting accountability, new famine theory focuses attention on the actors and the systems that shape starvation situations.

This paper critically analyzes ‘famine’ and its function in the Yemeni context, considering how its technical definition and operational frameworks – which have become gatekeepers to famine declaration – (mis)match the food security crisis in Yemen. It proposes a new conceptualization of famine beyond a lack of food, or fixating exclusively on physical and economic access to food. Instead, it centers political factors – and actors – that actively create famine conditions and the aid responses to them, which have failed to provide adequate famine-prevention interventions that are locally-driven and resilience-building.

A ‘new famine’ theory approach better explains Yemen’s experience of famine, where starvation is created through economic warfare and deprivation of resources. Through this lens, accountability is key to preventing and responding to famine in Yemen. Accountability and response can take place at local, national, and international levels.

At the local level, impacted communities should be able to make decisions about aid. There must be increased genuine local leadership to address multiple aspects of a food systems-focused response, centered around genuine accountability; such a response would moreover transcend artificial development and humanitarian divisions. While the aid sector recognizes that, with or without a famine declaration, ordinary Yemenis are suffering, current proposed adaptations or reforms are marginal.

Recent research in Yemen shows that local civil society is best placed to hold accountability. Therefore, the way forward must be driven and designed by Yemeni experts and civil society, who can best design famine prevention and response projects that are socio-culturally appropriate and relevant. At the same time, internationally-led responses should shift resources and ownership to locally-led efforts that understand the social structures that can provide buffers against famine.

A “new famine” prevention and response approach in Yemen that prioritizes accountability requires a diverse set of actions by international humanitarian and development actors, donor countries and institutions, and international multilateral institutions. Recommendations for these actions are offered at the end of this report.

Introduction

As the protracted crisis and costly humanitarian efforts in Yemen continue, a critical examination of internationally-led responses to acute food insecurity is overdue. The ongoing tendency to frame food insecurity as primarily about access to food reveals conceptual shortcomings and weakens practical responses in the context of Yemen. This paper critically analyzes the contemporary concept of ‘famine’ and its function in the Yemeni context, and considers how the theoretical bases that inform the technical definition of famine and operational frameworks (mis)match the food security crisis in Yemen.

Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) technical protocols have become gatekeepers to declaring famine, but the perpetual lack of data in Yemen has prevented a famine declaration being made. This paper proposes a new conceptualization of famine beyond IPC criteria, where famine is articulated as a condition created by multiple, often deliberate systemic failures that lead to hunger, disease and death. ‘New famine’ theory analyzes famine conditions without focusing on lack of food or fixating exclusively on physical and economic access to food. Instead, it centers political factors – and actors – that actively create famine conditions. This approach better describes Yemen’s experience of famine, where starvation is created through economic warfare and deprivation of resources. Through this ‘new famine’ lens, accountability is key to preventing and responding to famine in Yemen.

This paper relies on secondary sources and primary data collected from key informant interviews with international and national aid workers and researchers during late 2020 and early 2021. Interviewees’ affiliations and identities have been anonymized.

1. History of Food Insecurity in Yemen

A brief history of Yemen’s socioeconomic development policy toward food security reveals the effects of the “development complex” that formed over decades of development policies designed by Western donors and international agencies in Yemen since the 1970s, which contributed to a shift from self-reliance to dependence.[1] As the most fertile area on the Arabian Peninsula,[2] Yemen’s agricultural system used to be relatively sustainable[3] and self-sufficient.[4] It is now irreparably reliant on food imports and its food system is devastated.

Before unification in 1990, North Yemen’s trade and economic policies enabled subsidized imports of grains from wealthier Global North countries that had heavily subsidized their domestic grain production for export to poorer Global South countries. This north-to-south, double-subsidized[5] system kept staple food prices low for Yemeni consumers, while it disincentivized local grain production, often in favor of domestic cash crops (e.g., qat), shifting Yemen’s agricultural system toward heavy reliance on the global food system.[6] These policies continued post-unification and, together with multiple other factors,[7] contributed to a fragile food system that collapsed into famine during the current conflict.

Development Assistance Pre-2015

In the post-1994 civil war period, Yemen’s Social Fund for Development (SFD) and Social Welfare Fund (SWF) were among the programs founded to alleviate unemployment and poverty brought on in part by conditional financial assistance[8] – the Structural Adjustment programs that Yemen received from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. This assistance reduced state spending – including on subsidies for food, fuel and basic commodities – weakening household purchasing power to buy food, which was increasingly imported. The negative short-term outcomes of these austerity measures were considered necessary by their architects, who claimed they could be remedied by social welfare services,[9] such as social safety net programs through the SWF, which comprised 1.4 percent of GDP by 2008.[10]

Although over time the SWF and SFD have struggled to keep pace with the needs of Yemenis, they are among the more functional – and relatively politically neutral – of Yemen’s government programs. These programs adapted objectives over the years, and more recently aimed to contribute to improving food insecurity by reducing poverty. [11] [12] Poverty has been seen as a proxy indicator for food security (i.e., poverty indicates purchasing power to acquire food).[13] [14] While some advances were made between 1998 and 2006, the Triple F (food, fuel, financial) crisis of 2007/2008 hit Yemen hard and reversed those gains.[15] By 2010, Yemen was “near collapse”, with 30 to 40 percent unemployment, half of households in extreme poverty, and roughly one third of the population (7 million people) food insecure.[16] Yemen ranked 74th out of 84 countries in the Global Hunger Index 2010 and was “highly vulnerable to external shocks in the future”.[17] While the scale of Yemen’s social services has been recognized, the magnitude of challenges overwhelmed these institutions long before 2015.

Humanitarian Aid Pre-2015

Food security strategies within humanitarian responses in Yemen mirrored the internationally-driven governmental development policy focus on household access to food. The first UN-led Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) in 2010 included a Food Security and Agriculture Cluster (FSAC) strategy that prioritized food baskets for internally displaced people, with much smaller targets for livestock and seed support for farmers. It also underlined the need for linkages between humanitarian action and longer-term development.[18] The annual HRP for 2014 included humanitarian emergency relief and development-oriented community recovery concurrently and in a “complementary fashion.”[19] This included more focus on resilience-building activities, closely resembling the humanitarian-development nexus,[20] which refers to the policy-based and practical linking of these typically isolated types of aid.[21]

2. Operational Responses to Acute Food Insecurity Post-2015

Years before Yemen’s crisis was labeled the world’s worst, it was flagged as “one of the world’s major humanitarian crises”[22] in 2013, with 10.5 million food insecure people. In 2015, mere months after the launch of the Saudi-led coalition offensive, the famine risk was raised due to compounding factors resulting from the conflict.[23] By early 2017, there were warnings Yemen would “likely tip into famine.”[24] Today such warnings continue, while the FSAC’s HRP strategies have changed minimally; they continue to focus on food security through provision of food baskets and, to a lesser extent, food vouchers and cash transfers, with limited support for livelihoods.

Humanitarian Strategies Post-2015

The humanitarian sector’s strategies have recently departed from a “food first”[25] approach in famine response, promoting integration across key sectoral clusters in the 2018 and 2021 HRPs.[26] However, the dominance of the FSAC and its food supply in Yemen remains noteworthy. The FSAC, which continues to favor in-kind food distributions as indicated in their funding (detailed in section four), accounted for an average of 43 percent of the total annual appeals within the UN funding pool between 2011 and 2019.[27] [28] Meanwhile, the Early Recovery Cluster, more focused on restoring livelihoods, accounted for an average of 4 percent of the total[29] until it was discontinued in 2016, leaving the FSAC ostensibly responsible for humanitarian support for livelihoods as well.

Despite increased rhetoric about the nexus in more recent HRPs, food security and livelihoods programs remain siloed, based on the logic of segregation according to each agency’s mandate. For example, the World Food Programme (WFP) provides temporary access to food for people (humanitarian relief) while the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) facilitates continuous access to food, and supports more of the food system (recovery and development). Yet, aside from basic coordination (and some nexus-ization)[30] within the FSAC, internationally-led aid interventions remain divided between development and humanitarian, and within the latter, have made only nascent efforts to consider more than food supply.

In 2017, the Integrated Famine Risk Reduction (IFRR) was launched, following a recognition[31] that development and so-called humanitarian-plus programming actually included a more integrated famine response than the HRPs. The IFRR’s aim is to improve the effectiveness of different clusters’ efforts to reduce famine risks, though its impact has only been seen on cluster coordination, not on famine prevention itself.[32]

Development Assistance Post-2015

The FAO, active in Yemen since 1974, is responsible for supporting agricultural livelihoods as part of improving food and nutrition security. Its Plan of Action 2018–2020[33] has implemented longer-term interventions intended to complement the HRPs’ short-term activities through a “twin track” approach, including emergency support and livelihoods restoration, plus coordination through its role as co-lead of the FSAC with the WFP. The Plan’s annual Emergency Livelihood Response Plans (ELRP) detail specific 12-month interventions. For example, the 2018 ELRP was designed within the HRP framework to strengthen agricultural livelihoods in areas of severe food insecurity, reaching 5.7 million people with emergency support – US$57 million or 4.5 percent of the FSAC’s appeal – intended to decrease annually as livelihood restoration spending increases.[34] Over the same year, the FSAC requested US$1.35 billion (US$1.04 billion received)[35] to be spent on “immediate life-saving emergency food assistance”.

The Emergency Crisis Response Project (ECRP) is the largest of the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) portfolio in Yemen since 2015. It is the IDA’s nexus pilot project, partnering with UNDP and working through the Social Fund for Development and the Public Works Project for economic recovery ($848.58 million) discussed below. IDA funding constitutes what is known as humanitarian plus initiatives, intended to help transcend the humanitarian-development divide.[36] Such programming includes multi-year projects that support both individual livelihoods and communal resources, while working through existing government institutions.

Many of the food security and agricultural livelihood activities of the World Bank, FAO, WFP, and other FSAC actors are barely distinguishable from each other – and they all resemble the promoted activities of the Early Recovery Cluster and FSAC in pre-2015 HRPs. Essentially, there is nothing new about the strategies and modalities of food security and livelihood responses between “humanitarian” livelihood interventions and those classed as “development” or “nexus”, despite a worsening situation and recurrent famine forecasts.

3. The Theoretical Base of Famine and How it Functions in Yemen

Famine theory has shifted substantially from the Malthusian concept of famine as severely limited food availability.[37] The “entitlement approach”, developed by economist Amartya Sen in the 1980s, framed famine as a failure of people’s exchanges of entitlements (for example, labor or assets for food), thus articulating famine as a condition in which inhibited economic access to food leads to hunger, disease and death, usually as a result of unequal economic power.[38] Current researchers have pushed the theory further to frame famine as a condition created by multiple systemic failures, or as the result of the manipulation of systems of food access.[39] These are features of the ‘new famines’ which scholars argue have been seen in recent decades. This theoretical approach understands famines not just as failures of food availability or access to food, but as “failures of accountability and response.”[40] Given that armed conflict is usually the primary cause of acute food insecurity today,[41] ‘new famine’ theory focuses more on systemic challenges, political struggles and conflict. Some experts have highlighted the inadequacies of the current concepts and practical approaches to famine, as well as the methodologies that dictate famine classifications.[42]

The current prevailing narrative of famine in the aid sector presents it as a failure of food availability and access, and acknowledges it occurs as a result of human actions, rather than as arising primarily from natural disasters such as drought. However, the notion of accountability has not been sufficiently centered in discussions of famine. Accountability, rooted in ‘new famine’ theory, argues for greater focus on the actors and the systems that shape situations of starvation and the aid responses to them.

Determining the precise and direct causes for collective and individual failures to prevent famine-like conditions is beyond the scope of this paper. The failures of parties to the conflict have been addressed by researchers including the UN’s Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen, the World Peace Foundation and Global Rights Compliance, and Mwatana for Human Rights. This paper focuses on aid and concepts of famine in the context of international development and humanitarian efforts.

Conceptual: Academics agree that a ‘famine’ declaration should be based on quality data which meet strict criteria.[43] At the same time, given the challenges of mortality data[44] in Yemen, “a million people could die without a … famine being declared.”[45] It should also be recognized that ‘famine’ does not belong only to the IPC. In Alex de Waal’s seminal research on Sudan, where famine also emerged in the context of political, military and economic conflict,[46] de Waal found that different kinds of famines could result in hunger and/or destitution – and sometimes death, while the facets of famine extend beyond mass hunger and death, and include social breakdown and destitution, with a focus on the latter. [47] One of de Waal’s most emphatic conclusions is that analyses of famines must consider how famine is “articulated by the people who are suffering it.”[48]

Indeed, many Yemenis, when speaking of famine, refer to their lack of salaries and inability to find jobs and perceive famine based on loss of livelihoods that results in destitution and starvation. While the IPC includes livelihood-related factors and outcomes in its analytical framework,[49] famine declaration is based additionally on mortality and morbidity data.

The adoption of IPC as the (only) global standard for identifying famine reinforces two situations, both playing out currently in Yemen. First, it signals a commitment to the “technologization of famine” wherein “what counts as true is what scientific research can demonstrate.”[50] A household, community, or whole segment of Yemen could have experienced the deprivation, hunger, destitution, illness or death that characterizes famine; but IPC methodology precludes data such as subjective personal accounts of these conditions, and famine remains a technical concept. In this context, suffering in ‘famine-like conditions’ over years does not garner the attention for accountability as readily as does a famine declaration. Yemen’s case does, however, prove that the so-called specter of famine is effective in the fundraising of aid (e.g., creating food availability and access).

Second, the IPC system causes fixation on present and near-term conditions; famine is not a single event, however. The ‘new famines’ such as those we see in Yemen are slow onset crises rooted in historical changes in the food system and agricultural production, which have created and exacerbated disparities, particularly for those in rural areas. With new theories can come new imaginations, as explored later.

Technical: The IPC is considered an effective classification and early warning system, despite its notable limitations. Its technical protocols have become the gatekeepers of famine declaration, drawing skepticism from humanitarian practitioners and critique from researchers who note that the IPC process is challenged[51] in most humanitarian crises and does not fully capture[52] magnitude or duration. In Yemen, the failure of the IPC to enable a famine declaration is due to two primary factors. First, there is insufficient data on malnutrition, mortality, food consumption or livelihoods – all required to declare famine. The authorities and security dynamics impose physical and administrative access restrictions across Yemen, thus preventing necessary data collection.[53] Second, the consensus required at international and country levels is influenced by politics (and debates within the IPC),[54] even though the IPC was designed as an explicitly apolitical process. In Yemen (as in many ‘new famine’ situations) parties to the conflict have strategic reasons to promote or suppress a famine declaration according to how it reflects on their adversaries’ military – and in Yemen’s case, economic[55]– tactics.

Even if technical criteria for data quality were adjusted for access-constrained contexts, or famine was framed based on qualitative data that is more feasible to collect in conflict settings (e.g., first-hand accounts of hunger and deprivation), data is and will remain a paramount challenge in conflict environments, especially in Yemen. IPC is and will remain a process that excludes accountability. Acknowledging this, most suggestions about new and improved technical tools are insufficient in the context of Yemen and within the framework of the new famines.

Political: ‘New famine’ theory aligns with the reality of famine in Yemen, where actors create starvation through economic warfare and deprivation of resources. These are presented as access-related aspects of an economic famine, but they are also related to accountability and should be addressed as such. The economic challenges imposed by conflict actors result in manipulated markets[56] that benefit and reinforce the authorities’ power[57] and create dire conditions for the population, who then become reliant on (mostly in-kind) food aid. Progress toward accountability is seen through the documentation of and recognition that all parties to the conflict contribute to famine conditions. They do this through: the military targeting[58] of food system infrastructure; bureaucratic impediments that stall[59] or prevent[60] aid distribution;[61] and economic policies that systematically exacerbate acute food insecurity.[62] More, however, must be done.

Operational: While Yemen has been characterized as an “income famine,”[63] where economic warfare has inflated food prices and devastated Yemenis’ purchasing power, it has not resulted in wholesale food shortages.[64] Yet, the FSAC still prefers in-kind food, which fundamentally addresses only the – now antiquated – Malthusian notion of food availability. More recent HRPs have reflected livelihood support but mostly favor interventions that do little to improve resilience. Donors also seem hesitant about shifts away from classic food security responses ahead of durable peace processes.[65] These factors perpetuate a cycle of basic aid to meet basic needs, while whole-system needs have persisted with little accountability. Although humanitarian actors are increasingly vocal[66] in calling out parties to the conflict[67] for weaponizing the economy and food aid, the aid sector should also be held accountable for its role in the political economy of famine in Yemen.

4. Ground Truths: International Famine Response and Opportunities

Although in-kind food assistance continues to dominate humanitarian funding for Yemen, more livelihood-oriented alternatives to temporary food aid have been programmed. The following examines responses which have supported food security and agricultural livelihoods since 2015, along the spectrum of emergency relief to recovery-type humanitarian aid to humanitarian plus, or the nexus.

Emergency Food Relief (UN)

The stated objective of the WFP’s recent emergency operations has been to prevent famine while concurrently enabling recovery and resilience. However, the funding proportions and beneficiary totals suggest otherwise. WFP in-kind food provision comprises most of the FSAC’s response, while support for livelihoods under the Early Recovery Cluster has been minuscule.

Figure 1: Funding Requested for Food Security and Agriculture Cluster by Year

|

Cluster by Year |

Cluster Requested (US$m) |

Total YHF Requested (US$m) |

% of Total YHF Appeal Requested for Cluster |

|

2019 Food Security and Agriculture |

2,209 |

4,190 |

53% |

|

2018 Food Security and Agriculture |

1,351 |

3,110 |

43% |

|

2017 Food Security and Agriculture |

1,074 |

2,340 |

46% |

|

2016 Food Security and Agriculture |

746 |

1,630 |

46% |

|

2015 Food Security and Agriculture |

792 |

1,600 |

49% |

|

2014 Food Security and Agriculture |

252 |

596 |

42% |

|

2013 Food Security and Agriculture |

284 |

706 |

40% |

|

2012 Food Security and Agriculture |

201 |

586 |

34% |

|

2011 Food Security and Agriculture |

114 |

292 |

39% |

|

2010 Food Security and Agriculture |

61 |

186 |

33% |

Source of data: OCHA Financial Tracking Service[68] (Author’s table)

Figure 2: Funding for Early Recovery Cluster by Year

|

Cluster by Year |

Cluster Requested (US$m) |

Total YHF Requested (US$m) |

% of Total YHF Appeal Requested for Cluster |

|

2016 Emergency Employment and Community Rehabilitation |

51 |

1,630 |

3% |

|

2015 Early Recovery |

49 |

1,600 |

3% |

|

2014 Early Recovery |

27 |

596 |

5% |

|

2013 Early Recovery |

38 |

706 |

5% |

|

2012 Early Recovery |

49 |

586 |

8% |

|

2011 Early Recovery |

11 |

292 |

4% |

|

2010 Early Recovery |

4 |

186 |

2% |

Source of data: OCHA Financial Tracking Service[69] (Author’s table)

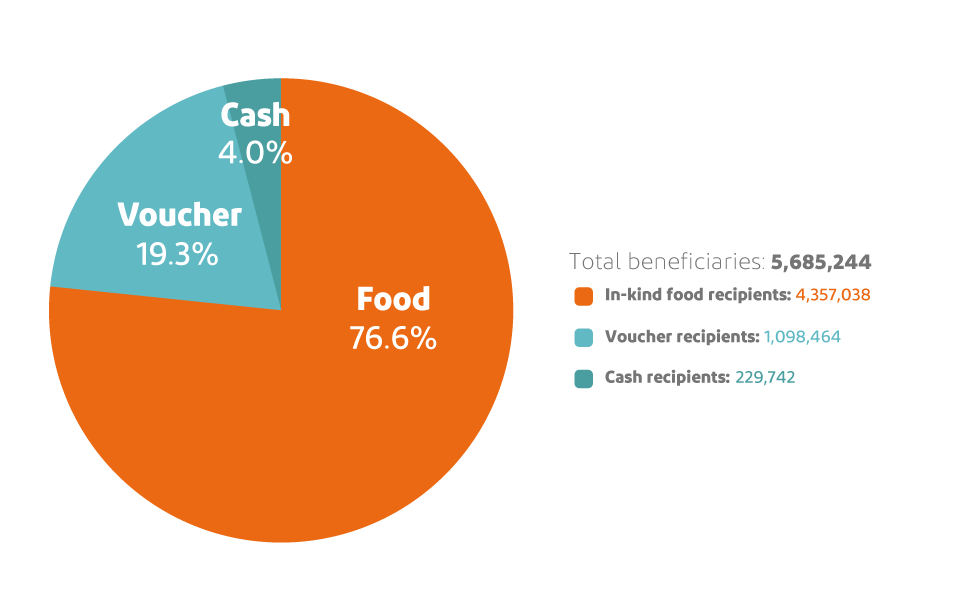

Even after the FSAC took over emergency livelihoods and recovery support in 2016, less than 0.5 percent of food security beneficiaries received livelihood support – an average of 33,000 out of 7.9 million beneficiaries between 2017 and 2019 (see Figure 3). Cash and vouchers comprised on average just 13 percent of funding for emergency food from 2017-2019. The rest funded in-kind food assistance (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Number of Beneficiaries of WFP Assistance by Type

|

World Food Programme in Yemen – Emergency Food Assistance (2017, 2018, 2019) |

|||||

|

Project Activity |

2019 Beneficiaries (Individuals) |

||||

|

Total Recipients |

Number of Recipients (food) |

% Recipients (food) |

Number of Recipients (cash or voucher) |

% cash or voucher |

|

|

Unconditional resource transfers to support access to food |

8,631,678 |

8,158,149 |

94.50% |

473,529 |

5.50% |

|

Asset creation and livelihood support activities |

— |

— |

— |

38,108 |

— |

|

Project Activity |

2018 Beneficiaries (Individuals) |

||||

|

Total Recipients |

Number of Recipients (food only) |

% Recipients (food) |

Number of Recipients (cash or voucher) |

% cash or voucher |

|

|

Unconditional resource transfers to support access to food |

7,904,762 |

6,668,627 |

84.40% |

1,819,289 |

23.00% |

|

Asset creation and livelihood support activities |

— |

— |

— |

28,217 |

— |

|

Project Activity |

2017 Beneficiaries (Individuals) |

||||

|

Total Recipients |

Number ofRecipients (food) |

% Recipients (food) |

Number of Recipients (voucher) |

% (voucher) |

|

|

Unconditional resource transfers to support access to food |

7,310,453 |

6,446,639 |

88.20% |

863,814 |

11.80% |

|

Asset creation and livelihood support activities |

not implemented (due to “funding constraints” and conflict escalation) |

||||

Source of data: WFP’s Standard Project Reports 2017, 2018, 2019[70]

Although Yemeni social and economic development experts have called for increased humanitarian cash assistance,[71] as of 2020, only 4 percent of recipients of emergency food assistance received cash assistance (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Beneficiaries of Yemen Food Security and Agriculture Cluster by Type of Assistance

Source of data: Yemen Food Security and Agriculture Cluster (FSAC)[72]

The WFP rationalizes its targeting by allocating in-kind food aid for rural households and focusing market-based cash/voucher assistance on non-rural households. But this justification is weak: most Yemeni households rely on markets for their staple foods, including rural households which farm or raise livestock. Also, markets have remained relatively stable in terms of food availability/supply (food price inflation and currency depreciation being the real barriers). Households that require transportation to markets, upon which they normally rely for food, must travel to receive food distributions. If transportation costs are incurred in obtaining food regardless, at least cash assistance provides choice. Furthermore, in-kind food aid is cost inefficient[73] and there are many anecdotal reports of WFP commodities being sold in markets.[74] As for accountability, beyond a hotline and media campaigns, there is no indication that beneficiaries have been consulted on their preference for cash, vouchers or in-kind assistance.

Livelihoods Recovery (International Non-Governmental Organizations)

Humanitarian organizations have attempted to incorporate more food systems-oriented programming into their responses. However, such projects are often small-scale, under-reported, and face particular challenges. For example, one INGO attempted an innovative agricultural livelihoods pilot project supporting mostly women farmers to create seed banks and cultivate community and home gardens, with permaculture integration, and cash-for-work and micro-grant schemes. While authorities in the north purported to welcome the initiative, they persistently imposed barriers to its implementation that nearly derailed the project. The INGO underwent more than a year of arduous negotiations around the authorities’ demands for selecting program locations and participants, and over the collection of sensitive project information (outside that provided in organizational sub-agreements). Finally, the organization compromised on some of the authorities’ “terms and conditions.”[75]

Humanitarian Plus/Nexus (World Bank)

An early example of explicit ‘nexus’ programming in Yemen, the Emergency Crisis Response Project, launched by the World Bank in 2016, was one of the first development-oriented projects in an armed conflict setting and included a substantial focus on agricultural livelihoods. Its design is not revolutionary: FSAC activities in recent HRPs and the above-mentioned INGO project include similar temporary cash-for-work, community asset rehabilitation activities, and support for smallholder farmers and fisherfolk. But a few features slightly distinguish ECRP from its humanitarian livelihood counterparts. For example, it includes “conflict sensitivity, social cohesion and institutional capacity development”,[76] which humanitarians rarely consider, often because they see them as outside their mandate. The ECRP also promotes its comparative cost effectiveness against humanitarian assistance (US$101 per individual versus US$114 for HRP food aid); and highlights its added benefits, like enhanced economic activity through support to small businesses and improved local infrastructure and income sources through labor works.[77]

Opportunities Within the Internationally-Led Response

The above-mentioned INGO pilot project and the World Bank’s nexus investment described above show there is the possibility of going beyond humanitarian business-as-usual and a comparatively more food systems-focused response to near-famine conditions. At the same time these and other livelihoods and market-based activities could be improved, based on the following observations:

- There is little sign of meaningful partnership with community organizations, informal institutions, or local civil society, nor of contextual tailoring to the socio-cultural, economic and political realities. World Bank officials have acknowledged the need for more partnerships with civil society outside formal institutions.[78] Opportunities for this are outlined further below.

- There is scope to partner with market actors further along the value chain (not just producers), which is proven[79] to be effective. There is also scope to review and incorporate aspects of previous government strategies for food security and agriculture, such as the National Food Security Strategy and National Agriculture Sector Strategy that might further reinforce the sustainability and capacity of the SFD, SWF, Public Works Project, etc.

- Aid workers have noted operational shortcomings on the ground. These include: inflated cash-for-work compensation that damaged the casual labor market; and water source rehabilitation and land restoration projects that resulted in increased qat production.[80] Agricultural livelihood initiatives need to address qat’s social and economic dominance (as the second largest source of employment)[81] with viable production alternatives that are sensitive in sociocultural terms.

Empowerment of Local Civil Society

Internationally-led humanitarian and development efforts have made minimal progress toward genuinely empowering local organizations and civil society to deliver aid according to their expertise and communities’ desires. Also, they have not facilitated them in functioning as agents of accountability. This must change. Within the context of ‘new famine’ in Yemen, there must be increased genuine local leadership to address multiple aspects of a livelihood and food systems-focused response, centered around genuine accountability and transcending artificial development and humanitarian divisions.

The Yemen Humanitarian Fund (YHF) promotes itself as among the largest sources of direct funding for national NGOs,[82] having allocated US$172 million to national NGOs since 2017. More than 50 percent of funded projects are implemented by national NGOs, and the YHF allows national NGO representation on its Advisory Board and Allocation Review committees. The YHF and humanitarian actors also promote training and capacity building for local partners on humanitarian principles, management and technical expertise.

This is an important first step. But international aid governance remains hesitant about letting go[83] of its authority and its paternalistic tone which dictates that local aid and civil society actors cannot be allowed to ‘get it wrong’.[84] Aid agencies made commitments to localization[85]– the shifting of resources and influence from international to local and national organizations – through global-level initiatives. These include the Localization Workstream within the Grand Bargain, born from the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit. In practice, however, instead of genuine localization, international agencies often design a project and hand it to a local entity with pre-selected activities to implement.[86] Local Yemeni civil society should be able to take decisions about aid and be held accountable by communities, to whom they are far more beholden than to international organizations.

The localization efforts promoted in HRPs and institutional support integrated into the ECRP are overdue first steps. The way forward, however, must be driven by Yemeni experts and civil society, who can best design socio-culturally appropriate and relevant projects. Internationally-led responses should shift resources and ownership to local organizations, which have greater awareness of the context that may be “baffl[ing] to aid workers,”[87] such as informal safety nets[88] that act as a buffer against famine.

Within an accountability framework, food security is a whole-food system issue which requires action and support beyond household-level access to food toward famine prevention through strengthening the food system. Civil society and community structures can develop this at local levels, reinforcing multiple points along the value chains. Local organizations can develop strong, trust-based relationships and facilitate community-driven economic activity in which social networks enable the market. Moreover, meaningful local leadership and equitable partnerships[89] can lead to more appropriate and sustainable solutions for sensitive systemic factors impacting food security, poverty and agriculture.

The FAO highlights the accountability of each actor[90] involved in realizing food security in crises. But it is rare to see clear demonstrations of learning from local actors or the incorporation of those lessons into strategy and program design, demonstrating a hierarchical relationship rather than a true partnership. Local staff working in international organizations have also expressed concern that localization efforts could put their jobs at risk, particularly if international organizations continue to draw and retain staffing and financial resources (i.e., maintaining control) while concurrently promoting small-scale localization efforts that keep local organizational capacity limited.[91] Such concerns reveal how deep and economically entrenched the power dynamics are between international agencies and local civil society.

5. New Imaginations

In 2010, donors and government officials expressed dismay at the superficial impact[92] of programs in Yemen. Eleven years on, Yemen is returning to the “brink of famine”[93] and has reportedly done so every year since 2015. These warnings do not encourage parties to the conflict to go to the negotiating table, and they no longer garner funding as in previous years. A conceptual re-framing of famine is needed in Yemen, as well as meaningful scrutiny of the design and implementation of food security interventions. There must also be accountability mechanisms for the aid industry, especially as it has replicated much of the state in terms of service provision in Yemen. Greater collective approaches to communication and community engagement[94] can facilitate accountability regarding food security and famine prevention and response.

The nature of ‘new famines’ emerging in protracted armed conflicts indicates that factors beyond food availability and access need to be the focus, with a sharpened structural view of catastrophic food insecurity. This can be called food system accountability, which emphasizes whole food system failure[95] of accountability and insufficient famine prevention. This focuses on conflict actors who commit famine crimes as well as international aid actors that fail to provide resilience-building, locally-driven interventions to prevent famine.[96] In the political economy of famine in Yemen, food system accountability analyzes the whole assemblage of policies and practices of conflict actors, aid actors, societal networks and communities that are implicated in, responding to, and subjected to famine. In this view, responses to famine can take place at local, national and international levels, and actors can be held accountable at all levels.

International Accountability

As global attention to food security and human rights[97] increases, and new famines emerge in complex conflicts, accountability should be pursued at international levels. International and national actors should heed repeated calls to sever support[98] to conflict parties; to fund essential aid rather than cutting it[99] or unilaterally withdrawing[100] it; and to address macro-economic issues[101] that create famine conditions. Important work by Mwatana for Human Rights and the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies[102] to hold parties to the conflict accountable for violations of international humanitarian law (IHL), and human rights law should be recognized and supported, as should the work of the World Peace Forum and Global Rights Compliance[103] on famine crimes such as weaponizing food availability and access. This work should be systematically monitored to ensure that international legal accountability processes follow Yemeni-led visions.

Local Accountability

Recent research in Yemen[104]shows that local civil society is perceived as neutral and well placed to pursue accountability. More work must be done to empower Yemenis to hold authorities and leaders accountable at a local level, where legitimacy is earned.[105] International actors should reinforce local-level accountability through support to local civil society and community structures.[106] This could include empowerment through promoting concepts such as the right to food and a local-level famine-prevention social contract between governing authorities and the impacted population.[107] Civil society could then translate these rights-based frameworks into locally sensible advocacy, and work to hold authorities accountable, regardless of who is the legal duty bearer. Civil society can also, as contextually appropriate, call out the weaponization of aid[108] and economic and social harm committed by local authorities..[109] To the extent that risks can be mitigated and organizations and individuals protected, Yemeni civil society can also be supported to document[110] violations of human rights and humanitarian law, including famine crimes.

Sophisticated due diligence and capacity building processes already exist which can help operationalize meaningful international-local partnership, well-developed over years of such partnership in other contexts such as Syria. These approaches can be adapted to the Yemen context to empower and build operational and technical capacity of local organizations and structures, and vet and monitor as necessary. Entrusting local and traditional accountability mechanisms to enforce sound practice would complement this.

Donors and international organizations should ask what is needed – for example, technical training, financial support, high-level negotiation and advocacy etc. – to enable local civil society and community social structures (essential to survival in Yemen[111]) to negotiate and facilitate famine prevention according to local needs and priorities, with greater flexibility based on the context. To do so, donors and international aid actors will need a deeper understanding of the complex power structures and their roles in the local political economy of famine. Fortunately, research continues to emerge on political economy, accountability frameworks, and famine in Yemen, as well as engaging communities in these contexts.[112]

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

The aid sector recognizes that, with or without a famine declaration, ordinary Yemenis are suffering greatly. Yet marginal reforms – as well as quick fix interventions[113]– are almost wasteful at a time when donors’ accounts are stretched thin. A ‘new famine’ prevention and response approach that prioritizes accountability requires a diverse set of actions.

Recommendations:

For International Humanitarian and Development Actors:

- Acknowledge that Yemen’s famine is composed of vastly different levels of severity, scale, and magnitude. Therefore, famine response must be tailored to localities (e.g., as per specific agro-ecological zones[114]). It must also be more comprehensive in terms of sectors (e.g., health, nutrition, water, sanitation, and hygiene), and more inclusive of perspectives and recommendations from the impacted local population.

- Incorporate concrete plans into current and future aid strategies to transfer ownership of famine prevention and response (including priority-setting, modality design and monitoring mechanisms) to community-level and civil society organizations who can best enable local accountability. Through a phased approach, make a goal to fund those entities directly.

- Work with existing advocacy and food security actors to continue raising awareness of the incidence of hunger atrocities, and advocate for the implicated parties (and their allies) to change course or be punished through intergovernmental mechanisms.

- Strengthen advocacy toward accountability of belligerents who commit starvation/famine crimes, making substantial space for Yemeni voices (beyond malnutrition victims and aid beneficiary stories).

- Increase the proportion of humanitarian assistance provided through food systems-focused responses, specifically by:

- Decreasing the provision of expensive and logistically intensive in-kind food provision to increase timely, market-responsive and inflation-sensitive cash assistance,[115] encouraging support for entities like the Cash Working Group and collaboration with cash assistance agencies such as the Social Welfare Fund.

- Vastly expanding economic support for livelihoods and along value chains, beyond simply cash-for-work schemes, encouraging collaboration between livelihoods actors within the FSAC, development actors such as the World Bank and its partners, and agencies such as the SFD.

- Implement the above-mentioned humanitarian activities, and all multi-sectoral aid responses, through substantially stronger and more meaningful collaboration with local civil society and community organizations, including technical and operational support, as well as transfer of decision-making to those local actors.

- Review and report candidly on famine prevention efforts, in terms of both effectiveness and connectedness,[116] within the ongoing Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation (IAHE) of the Yemen Humanitarian Response, paying particular attention to accounts from people in Yemen who received food aid, in-kind and via cash or vouchers. Reporting should include qualitative data in addition to quantitative data to capture realities faced,[117] given IAHE-acknowledged constraints.

For Donor Countries and Institutions

- Promote accountability in famine prevention and response, including accountability from fellow donor countries involved in the military and economic conflicts.

- Significantly fund locally driven, systems-focused and accountability-centered food security programming, with or without a famine declaration.

- In programming, wherever possible, transfer leadership and ownership in substantial, meaningful ways to local community structures and civil society.

- Invest substantially and directly in local civil society, exceeding minimums stipulated in the Grand Bargain wherever possible.

- Invest more and longer-term funding into food systems-focused projects with robust nutrition-sensitive agriculture and livelihoods aspects, and gradually reduce spending on emergency in-kind food relief, driven by objectives such as those raised above, in Recommendation 5.

For International Multilateral Institutions

- Heed humanitarian advocacy and push for accountability of parties to the conflict who commit starvation/famine crimes – as documented by the Human Rights Council Experts on Yemen[118] and other organizations and researchers,[119][120] and facilitate accountability for parties who weaponize the economy.

- Make famine through economic deprivation a war crime or crime against humanity, in addition to “starvation” tactics under the Rome Statute’s Article 8(2)(b)(xxv) and UN Security Council Resolution 2417 (2018), and facilitate actions to incorporate such crimes into IHL, guided by ongoing research on gaps in international law.[121]

- Continue to pressure authorities using economic warfare to change policies that drive up food prices, and negatively impact livelihoods (for example, de facto blockades, suspended salary payments, and loss of remittances due to deportation of Yemeni expat workers from other countries).

For Local Civil Society in Yemen

- Continue to demand commitment to genuine localization of famine prevention and response through contextually appropriate strategies and approaches.

- Promote Yemeni perceptions and experiences of famine and demand their consideration within the present technological frameworks of famine in Yemen.

This edition of the Yemen Economic Bulletin is part of the Sana’a Center project Monitoring Humanitarian Aid and its Micro and Macroeconomic Effects in Yemen, funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. The project explores the processes and modalities used to deliver aid in Yemen, identifies mechanisms to improve their efficiency and impact, and advocates for increased transparency and efficiency in aid delivery.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover diplomatic, political, social, economic and security-related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

-

Professor Martha Mundy used this term to refer to the various international agencies (e.g, International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank (WB), United Nations’ (UN) Development Program (UNDP), and the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)) that have contributed to policies that drove Yemen’s shift from agricultural self-reliance in terms of staple foods, to its dependence on imports from the 1970s – largely in the Saleh-run Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) – through unification up to today. Mundy notes that post-2015, international aid actors emerged in “a kind of government of humanitarianism in Yemen”: Martha Mundy, “The future of food and challenges for agriculture in the 21st Century – The war on Yemen and its agricultural sector,” ICAS-Etxalde Colloquium, April 2017, http://elikadura21.eus/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/50-Mundy.pdf and Martha Mundy, “The Strategies of the Coalition in the Yemen War: Aerial bombardment and food war,” World Peace Foundation, October 9, 2018, https://sites.tufts.edu/wpf/strategies-of-the-coalition-in-the-yemen-war/

-

Daniel Martin Varisco, “Agriculture in the Northern Highlands of Yemen: From Subsistence to Cash Cropping,” Journal of Arabian Studies, March 19, 2019, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/21534764.2018.1551470

-

See Max Ajl, “Yemen’s Agricultural World: Crisis and Prospects” in Crisis and Conflict in Agriculture, (Wallingford: Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International, 2018) and Max Ajl, “Does the Arab region have an agrarian question?”, The Journal of Peasant Studies, May 20, 2020.

-

Daniel Martin Varisco, “The State of Agriculture in the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen, 1918-1962,” Austrian Academy of Sciences, Volume 321: 1, revised version, July 2019,https://epub.oeaw.ac.at/0xc1aa5576_0x003ac93e.pdf

-

Martha Mundy, Amin Hakimi, and Frederic Pelat “Neither Security Nor Sovereignty the Political Economy of Food in Yemen,” Oxford Scholarship Online, December 2014, 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199361786.003.0006

-

See C. Ward, “The political economy of irrigation water pricing in Yemen,” in The political economy of water pricing reforms, (Washington DC, The World Bank, 2000) and Najwa Adra, “The Impact of Male Outmigration on Women’s Roles in Agriculture in The Yemen Arab Republic”, Food and Agriculture Organization, revised January 2013, http://www.najwaadra.net/impact.pdf

-

These include government-subsidized fuel and increased remittance wealth, which enabled diesel powered cultivation, among many other factors. See: Najwa Adra, “The Impact of Male Outmigration on Women’s Roles in Agriculture in The Yemen Arab Republic”, Food and Agriculture Organization, revised January 2013, http://www.najwaadra.net/impact.pdf and Max Ajl, “Yemen’s Agricultural World: Crisis and Prospects” in Crisis and Conflict in Agriculture, (Wallingford: Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International, 2018)

-

Nora Ann Colton, “Yemen: A Collapsed Economy,” Middle East Journal, 2010, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40783107?seq=1

-

Nader Fergany, “Structural Adjustment versus Human Development in Yemen,” in Kamil Mahdi, Yemen into the Twenty-First Century: Continuity and Change, (Ithica Press, March 1, 2007), https://www.scribd.com/book/353208466/Yemen-into-the-Twenty-First-Century-Continuity-and-Change

-

Mirey Ovadiya, Adea Kryeziu, Syeda Masood and Eric Zapatero, “Social Protection in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Countries: Trends and Challenges,” The World Bank Group – Social Protection and Labor, April 2015, https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/951221468185039094/social-protection-in-fragile-and-conflict-affected-countries-trends-and-challenges. Note: according to a 2015 World Bank report, the average government spending on social safety nets by low-income countries is 1.4 percent of GDP. Government safety net expenditure reflects resource capacity, as well as “policy priorities” and “contextual factors,” according to the report. In the case of Yemen, the above mentioned cuts in government subsidies account for the need for social safety nets.

-

Thabet Bagash, Paola Pereznieto, and Khalid Dubai, “Transforming Cash Transfers: Beneficiary and community perspectives on the Social Welfare Fund in Yemen,” ODI, December 2012, https://odi.org/en/publications/transforming-cash-transfers-beneficiary-and-community-perspectives-on-the-social-welfare-fund-in-yemen/

-

Lamis Al-Iryani, Alain de Janvry & Elisabeth Sadoulet, “The Yemen Social Fund for Development: An Effective Community-Based Approach amid Political Instability,” International Peacekeeping, July 20, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2015.1064314

-

Olivier Ecker, Clemens Breisinger, Christen McCool, Xinshen Diao, Jose Funes, Liangzhi You, Bingxin Yu “Assessing food security in Yemen: An Innovative Integrated, Cross-Sector, and Multilevel Approach,” International. Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), August 2020, https://www.ifpri.org/publication/assessing-food-security-yemen

-

Definition: “Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” (World Food Summit, 1996). It has four dimensions – availability (supply), access (physical and economic), food utilization (and dietary diversity), and stability of these over time.

-

“Comprehensive Food Security Survey 2010,” World Food Programme, March 2010, https://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/ena/wfp219039.pdf

-

Farea Al-Muslimi and Mansour Rageh, “Yemen’s economic collapse and impending famine: The necessary immediate steps to avoid worst-case scenarios,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 5, 2015, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/26

-

Klaus von Grebmer, Marie T Ruel, Purnima Menon, Bella Nestorova, Tolulope Olofinbiyi, Heidi Fritschel, Yisehac Yohannes, Constanze von Oppeln, Olive Towey, Kate Golden, Jennifer Thompson, “2010 Global Hunger Index – The Challenge of Hunger: Focus on the Crisis of Child Undernutrition,” International Food Policy Research Institute, Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe, October 2010, https://www.ifpri.org/publication/2010-global-hunger-index-challenge-hunger

-

“Consolidated Appeals Process (CAP): Mid-Year Review – Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan 2010,” Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), July 13, 2010, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/consolidated-appeals-process-cap-mid-year-review-yemen-humanitarian-response-plan-2010

-

“2014 Yemen Humanitarian Needs Overview,” OCHA, October 31, 2013, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/2014-yemen-humanitarian-needs-overview-engarabic

-

“Humanitarian Development Nexus: The New Way of Working,” OCHA, https://www.unocha.org/fr/themes/humanitarian-development-nexus

-

A 2016 World Humanitarian Summit draft background paper on the nexus details the conceptual and terminological aspects of the concept. “Concept Note: Joint workshop on the Humanitarian, Development and Peace Nexus,” The UN Working Group on Transitions and the IASC Task Team on Humanitarian and Development Nexus in protracted crises, September 30, 2016, https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/joint_workshop_concept_note_300916_rev1.docx

- “Humanitarian Response Plan for Yemen 2013,” OCHA, December 13, 2012, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/humanitarian-response-plan-yemen-2013

-

Farea Al-Muslimi and Mansour Rageh, “Yemen’s economic collapse and impending famine: The necessary immediate steps to avoid worst-case scenarios,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 2015, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/26

-

“Instruments of Pain (I): Conflict and Famine in Yemen,” International Crisis Group, April 13, 2017, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/yemen/b052-instruments-pain-i-conflict-and-famine-yemen

-

Stephen Devereux, Lewis Sida and Tina Nelis, “Famine: Lessons Learned,” Institute of Development Studies, September 1, 2017, https://www.ids.ac.uk/publications/famine-lessons-learned/

-

The 2018 HRP was the first to reference an integrated response to famine prevention across sectoral clusters, including water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), health, and nutrition, in addition to food security. However, the 2019 and 2020 HRPs did not explicitly promote integrated famine prevention, as their strategies mentioned only cross-sectoral activities. The 2021 HRP heavily emphasizes an overall integrated response, and refers to the IFRR. See: “Yemen: Humanitarian Response Plan January – December 2018,” OCHA, January 20, 2018, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-humanitarian-response-plan-january-december-2018-enar. “2019 Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan January – December 2019,” OCHA, February 19, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/2019-yemen-humanitarian-response-plan-january-december-2019-enar. “Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan, June – December 2020 Extension,” OCHA, May 28, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-humanitarian-response-plan-extension-june-december-2020-enar. “Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan 2021 (March 2021),” OCHA, March 16, 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-humanitarian-response-plan-2021-march-2021-enar

-

As per OCHA’s Financial Tracker Service for Yemen: https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/675/summary

-

The 2020 HRP was an extension of the 2019 HRP. Additionally, OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service figures for 2020 do not specify the total required and funded specifically for the FSAC, although totals for other clusters are noted: https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/925/summary

-

As per OCHA’s Financial Tracker Service for Yemen: https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/513/summary

-

“IASC Snapshot: Yemen’s New Way of Working”, Inter-Agency Standing Committee, June 14, 2017, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/iasc-snapshot-yemen-s-new-way-working

-

Spyros Demetriou, “Business Case Assessment for Accelerating Development Investments in Famine Response and Prevention, Case Study: Yemen,” UN Development Programme (UNDP), January 26, 2018, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/business-case-assessment-accelerating-development-investments-famine-response-and

-

Danka Pantchova, “Integrated Famine Risk Reduction: An Inter-Cluster Strategy to Prevent Famine in Yemen: A Case Study, (July 2020),” UNICEF/Global Nutrition Cluster, December 18, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/integrated-famine-risk-reduction-inter-cluster-strategy-prevent-famine-yemen-case-study

-

“Yemen Plan of Action – Strengthening resilient agricultural livelihoods 2018–2020,” FAO, April 2018, http://www.fao.org/resilience/resources/resources-detail/en/c/1113449/

-

“Yemen Emergency Livelihoods Response Plan 2018: Support to agriculture-based livelihoods,” FAO, April 2018, http://www.fao.org/emergencies/resources/documents/resources-detail/en/c/1113467/

-

As per OCHA’s Financial Tracker Service for Yemen (2018): https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/657/summary

-

“IASC Snapshot: Yemen’s New Way of Working,” Inter-Agency Standing Committee, June 14, 2017, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/iasc-snapshot-yemen-s-new-way-working

-

See, for example, Stephen Devereux, The new famines: why famines persist in an era of globalization, (London, Routledge, 2007).

-

See Amartya Sen, Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1983).

-

Jenny Edkins, “The criminalization of mass starvations: From natural disaster to crime against humanity,” in The new famines: why famines persist in an era of globalization, (London, Routledge, 2007).

-

Stephen Devereux, “Introduction: From ‘old famines’ to ‘new famines’,” in The new famines: why famines persist in an era of globalization, (London, Routledge, 2007), 2.

-

Alex de Waal, “Armed Conflict and the Challenge of Hunger: Is an End in Sight?” Global Hunger Index, 2015, https://www.ifpri.org/publication/armed-conflict-and-challenge-hunger-end-sight

-

For example, IBID, and Daniel Maxwell, Peter Hailey, Lindsay Spainhour Baker, Jeeyon Janet Kim, “Constraints and Complexities of Information and Analysis in Humanitarian Emergencies Evidence from Yemen,” Feinstein International Center, 2019, https://fic.tufts.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019-Evidence-from-Yemen-final.pdf

-

For example, Daniel Maxwell and Peter Hailey, “The Politics of Information and Analysis in Famines and Extreme Emergencies: Synthesis of Findings from Six Case Studies,” Feinstein International Center, 2020, https://fic.tufts.edu/publication-item/politics-of-information-and-analysis-in-famines-and-extreme-emergencies-synthesis and Jenny Edkins, “Mass Starvations and the Limitations of Famine Theorising,” Institute of Development Studies, October 1, 2002, https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/8636

-

The IPC’s Special Famine protocols include three outcomes which must exceed certain thresholds, based on data: more than 20% of households with extreme food gaps, global acute malnutrition (GAM) rate above 30% for children, and crude death rate higher than 2 per 10,000/day.

-

Quote by Alex de Waal, interviewed by Samuel Oakford, “Deaths before data,” The New Humanitarian, November 12, 2018, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2018/11/12/Yemen-war-conflict-deaths-data-famine

-

For comprehensive research on historical and contemporary famines, see Alex de Waal, Mass Starvation: The History and Future of Famine, Wiley & Sons, January 2018, https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Mass+Starvation%3A+The+History+and+Future+of+Famine-p-9781509524662

-

Alex de Waal, Famine that Kills: Darfur, Sudan, (University of Oxford/Oxford University Press, 2005), https://www.ssrc.org/publications/view/C66F4C09-5945-DE11-AFAC-001CC477EC70/

-

Ibid

-

Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) Global Partners, “Technical Manual Version 3.0,” 2019, http://www.ipcinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ipcinfo/manual/IPC_Technical_Manual_3_Final.pdf, p.35

-

Jenny Edkins, Whose Hunger? Concepts of Famine, Practices of Aid, (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2008), xvi.

-

Daniel Maxwell, Peter Hailey, Lindsay Spainhour Baker, and Jeeyon Janet Kim, “Constraints and Complexities of Information and Analysis in Humanitarian Emergencies: Evidence from Yemen,” Feinstein International Center, June 2019, https://fic.tufts.edu/publication-item/famine-and-analysis-in-yemen/

-

Daniel Maxwell, Peter Hailey, Abdullahi Khalif, Andrew Seal, Alex de Waal, Nicholas Haan, and Francesco Checchi, “Hunger deaths aren’t simply about famine or no famine,” The New Humanitarian, February 3, 2021, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/opinion/2021/2/3/yemen-famine-aid-hunger-crises-south-sudan-malnutrition

-

The latest IPC protocols purport to facilitate classification in contexts where constrained access limits the quantity and quality of data that can be collected – permitting that “minimum evidence is available and with the recognition that this analysis will provide less specific and less accurate information as a result” – it is not clear if this would help overcome the political challenge of famine declaration.

-

“Story in Focus: Interview with Dan Maxwell, Professor in Food Security at the Friedman School of Nutrition, Science and Policy,” World Peace Foundation/Global Rights Compliance, https://starvationaccountability.org/news-and-events/1009

-

“Yemen: Drivers of food insecurity,” ACAPS, April 12, 2019, https://www.acaps.org/special-report/yemen-drivers-food-insecurity

-

See, for example, David Keen, The benefits of famine: a political economy of famine and relief in southwestern Sudan, 1983-1989, (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994).

-

Peter Salisbury, “Bickering While Yemen Burns: Poverty, War, and Political Indifference,” The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, June 22, 2017, https://agsiw.org/bickering-while-yemen-burns-poverty-war-and-political-indifference/

-

Martha Mundy, “Strategies of the Coalition in the Yemen War: Aerial bombardment and food war,” World Peace Foundation, October 9, 2018, https://sites.tufts.edu/wpf/strategies-of-the-coalition-in-the-yemen-war/

-

The Panel of Experts on Yemen, “Letter dated 25 January 2019 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council,” UN Security Council, January 25, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/letter-dated-25-january-2019-panel-experts-yemen-addressed-president-security-council

-

The Panel of Experts on Yemen, “Final report of the Panel of Experts on Yemen (S/2020/326)” UN Security Council, May 5, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/final-report-panel-experts-yemen-s2020326-enar

-

Gerry Simpson, “Deadly Consequences – Obstruction of Aid in Yemen During Covid-19,” Human Rights Watch, September 14, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/09/14/deadly-consequences/obstruction-aid-yemen-during-covid-19

-

“Yemen: food supply chain,” ACAPS, December 16, 2020, https://www.acaps.org/special-report/yemen-food-supply-chain

-

Ibtisam Azem, “UN humanitarian coordinator Lise Grande: Without urgent help, Covid-19 will devastate what’s left of Yemen,” The New Arab, June 2, 2020, https://english.alaraby.co.uk/analysis/un-humanitarian-coordinator-lise-grande-covid-19-will-devastate-yemen

-

“Yemen: Food supply chain,” ACAPS, December 16, 2020, https://www.acaps.org/special-report/yemen-food-supply-chain

-

Author’s confidential interview with a humanitarian aid INGO advocacy official, August 9, 2020.

-

Mohamed Abdi, “World leaders can still avert famine in Yemen. Here’s how…,” The New Humanitarian, January 6, 2021, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/opinion/2021/01/06/yemen-famine-aid-funding-conflict

-

“Aid agencies: Rise in fighting threatens to push Yemen into new levels of violence as war enters seventh year,” Joint INGO Statement, March 23, 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/aid-agencies-rise-fighting-threatens-push-yemen-new-levels-violence-war-enters-seventh

-

OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service, https://fts.unocha.org/countries/248/summary/2021

-

Ibid.

-

“Immediate, Integrated and Sustained Response to Avert Famine in Yemen: Standard Project Report 2019,” World Food Programme in Yemen, 2019, https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000113903/download/. “Immediate, Integrated and Sustained Response to Avert Famine in Yemen: Standard Project Report 2018,” World Food Programme in Yemen, 2018, https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000103876/download/?_ga=2.93594143.306147164.1620566941-999754891.1615827973. “Immediate, Integrated and Sustained Response to Avert Famine in Yemen: Standard Project Report 2017,” World Food Programme in Yemen, 2017, https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000069876/download/?_ga=2.96707869.306147164.1620566941-999754891.1615827973

-

“Increasing the Effectiveness of the Humanitarian Response in Yemen,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, DeepRoot Consulting and CARPO, April 10, 2018, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/5592

-

“Emergency Food Assistance Needs and Gap analysis,” Yemen Food Security and Agriculture Cluster (FSAC), December 2020 Interactive Map, February 9, 2021, https://fscluster.org/yemen/document/emergency-food-assistance-needs-and-gap-4

-

Spyros Demetriou, “Business Case Assessment for Accelerating Development Investments in Famine Response and Prevention: Case Study Yemen,” UNDP, January 26, 2018, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/business-case-assessment-accelerating-development-investments-famine-response-and

-

Author’s experience and author’s confidential interview with an operational humanitarian INGO official, April 17, 2021.

-

Author’s confidential interview with an operational humanitarian INGO official, May 28, 2021.

-

Spyros Demetriou, “Lessons Learned Study: Yemen Emergency Crisis Response Project,” UNDP, September 30, 2019, https://www.ye.undp.org/content/yemen/en/home/library/lessons-learned-study-from-yecrp-.html

-

Ibid

-

Author’s confidential interview with a World Bank official, April 6, 2021

-

Rojan Bolling and Jacqueline Vrancken, “Quick-scan: Lessons of market-oriented food security programmes in fragile settings,” Food & Business Knowledge Platform, March 2020, https://www.thebrokeronline.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/aid-transition_quick-scan_report02.pdf

-

Author’s confidential interviews with two operational humanitarian INGO officials, April 17, 2021 and July 16, 2020.

-

Peer Gatter, Mustapha Rouis, and Steven Tabor, “Yemen: Towards Qat Demand Reduction,” The World Bank, June 2007, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/500871468183253500/pdf/397380YE.pdf

-

“Yemen humanitarian fund in brief 2020,” OCHA, February 25, 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-humanitarian-fund-brief-2020-enar

-

Christina Bennett, Matthew Foley, and Sara Pantuliano, “Time to let go: remaking humanitarian action for the modern era,” Overseas Development Institute, April 11, 2016, https://odi.org/en/publications/time-to-let-go-remaking-humanitarian-action-for-the-modern-era/

-

Quote from Marc DuBois during a webinar, “Re-envisioning Global Humanitarian Response,” May 2020, SOAS University of London Humanitarian Hub, May 2020, https://blogs.soas.ac.uk/humanitarian-hub/hhub-seminar-series/

-

Oheneba Boateng and Claudia Meier, “Sharing the Keys to the Localization House,” The Global Public Policy Institute, April 15, 2021, https://www.gppi.net/2021/04/15/sharing-the-keys-to-the-localization-house

-

Author’s first-hand professional experience in multiple contexts and countries, validated by international and local peers and colleagues.

-

Peter Salisbury, “Bickering While Yemen Burns: Poverty, War, and Political Indifference,” The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, June 22, 2017, https://agsiw.org/bickering-while-yemen-burns-poverty-war-and-political-indifference/

-

Daniel Maxwell, Abdullahi Khalif, Peter Hailey, and Francesco Checchid, “Viewpoint: Determining famine: Multi-dimensional analysis for the twenty-first century,” Food Policy, April 2020, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0306919220300166

-

“Rethinking Yemen’s Humanitarian Response Plan: Policy Brief,” SMEPS, June 2, 2019, https://smeps.org.ye/posts/reports

-

Committee on World Food Security, “Framework for Action for Food Security and Nutrition in Protracted Crises,” FAO, WFP, and IFAD, October 13, 2015, http://www.fao.org/policy-support/tools-and-publications/resources-details/en/c/423451/#:~:text=The%20objective%20of%20the%20Committee,addressing%20critical%20manifestations%20and%20building

-

Author’s confidential interview with an operational humanitarian INGO official, April 17, 2021.

-

Nora Ann Colton, “Yemen: A Collapsed Economy,” Middle East Journal, 2010, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40783107?seq=1

-

Anna McMorrin, “With Yemen on the brink of famine, the UK must not be an accomplice,” The New Humanitarian, March 8, 2021, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/opinion/2021/3/8/Yemen-on-brink-of-famine-UK-must-not-be-an-accomplice

-

Kerrie Holloway and Oliver Lough, “Implementing collective accountability to affected populations Ways forward in large-scale humanitarian crises,” Humanitarian Policy Group, October 15, 2020 https://odi.org/en/publications/implementing-collective-accountability-to-affected-populations-ways-forward-in-large-scale-humanitarian-crises/

-

It is well appreciated that in addition to food system failure, the collapse of the health sector, mass protracted displacement, climate and weather disasters, and insecurity all contribute substantially to Yemen’s famine.

-

It is well appreciated that non-belligerent local actors, especially elites such as tribal leaders, can also be deeply implicated in contributing to famine conditions by diverting or withholding aid and community support from certain individuals and marginalized groups. Research on this from the Yemeni perspective would enrich a ‘new famine’ conceptual framing.

-

Michael Fakhri, “Opinion: The future of food must include a commitment to human rights,” Devex, October 16, 2020, https://www.devex.com/news/opinion-the-future-of-food-must-include-a-commitment-to-human-rights-98325

-

Adva Saldinger, “Biden’s Yemen actions on right track but more is needed, experts say,” Devex, March 12, 2021, https://www.devex.com/news/biden-s-yemen-actions-on-right-track-but-more-is-needed-experts-say-99384

-

William Worley, “UK’s aid budget to Yemen slashed by nearly 60%,” March 1, 2021, https://www.devex.com/news/uk-s-aid-budget-to-yemen-slashed-by-nearly-60-99281

-

Missy Ryan, “As coronavirus looms, U.S. proceeding with major reduction of aid to Yemen,” The Washington Post, March 27, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/as-coronavirus-looms-us-proceeds-with-dramatic-reduction-of-aid-to-yemen/2020/03/26/61c15a00-6f77-11ea-96a0-df4c5d9284af_story.html

-

“Editorial: Famine at Hand Without a Reunified Central Bank to Protect the Yemeni Rial,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 16, 2018, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/6557

-

“European Parliament Adopts Resolution on Yemen, Calls on EU and Member States to Address Accountability Gap,” The Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS) and Mwatana for Human Rights, February 12, 2021, https://mwatana.org/en/resolution-on-yemen-2/

-

“Accountability for Starvation Crimes: Yemen,” World Peace Foundation and Global Rights Compliance, September 4, 2019, https://sites.tufts.edu/reinventingpeace/2019/09/04/accountability-for-starvation-crimes-yemen/

-

Marta Abrantes Mendes, “A Passage to Justice Selected Yemeni civil society views for transitional justice and long-term accountability in Yemen,” Open Society Foundations, February 2021, https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/publications/a-passage-to-justice and Marta Abrantes Mendes and Chris Rogers, “Put Yemen’s Civil Society – and Accountability — at the Center of the Push for Peace,” Just Security, March 2, 202, https://www.justsecurity.org/75072/put-yemens-civil-society-and-accountability-at-the-center-of-the-push-for-peace/

-

Peter Salisbury, “A multidimensional approach to restoring state legitimacy in Yemen,” International Growth Center, August 28, 2018, https://www.theigc.org/publication/multidimensional-approach-restoring-state-legitimacy-yemen/

-

Marta Colburn, “A New Path Forward: Empowering a Leadership Role for Yemeni Civil Society,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, January 27, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/13021

-

See Stephen Devereux, Lewis Sida and Tina Nelis, “Famine: Lessons Learned,” Institute of Development Studies, December 01, 2017, https://www.ids.ac.uk/publications/famine-lessons-learned/ and Stephen Devereux, The new famines : why famines persist in an era of globalization, (London, Routledge, 2007).

-

Joost Hiltermann and April Longley Alley, “How All Sides of Yemen’s War Are Weaponizing Hunger and Creating a Famine,” World Politics Review, April 27, 2017, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/21977/how-all-sides-of-yemen-s-war-are-weaponizing-hunger-and-creating-a-famine

-

Ibid

-

Ibid

-

Jeeyon Kim, Alex Humphrey, Maha Elsamahi, Aws Kadasi, Daniel Maxwell, “I Could Not Sleep While They Were Hungry”: Investigating the Role of Social Networks in Yemen’s Humanitarian Crisis, Mercy Corps, April 2021, https://www.mercycorps.org/research-resources/yemen-study-social-networks

-

Sherine El Taraboulsi-McCarthy, Yazeed Al Jeddawy and Kerrie Holloway, “Accountability dilemmas and collective approaches to communication and community engagement in Yemen,” Humanitarian Policy Group, July 2020, https://odi.org/en/publications/accountability-dilemmas-and-collective-approaches-to-communication-and-community-engagement-in-yemen/

-

Ben Parker and Annie Slemrod, “Exclusive: The biggest Yemen donor nobody has heard of,” The New Humanitarian, March 1, 2021, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2021/3/1/mysterious-new-yemen-relief-fund-aims-to-stop-famine

-

Stephen Browne, “Livelihoods zoning “plus” activity in Yemen: A special report,” Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS NET), 2010, https://fews.net/sites/default/files/ye_zonedescriptions_en.pdf

-

Changes in the proportions of each modality should no doubt be gradual, but the push for such shifts should see an expedited pace, based on the economic realities in different localities.

-

These are two of the four aspects of the IAHE evaluation questions and sub-questions. See “Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation of Yemen Crisis, Inception Report,” August 2021, https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/inter-agency-humanitarian-evaluations/inter-agency-humanitarian-evaluation-yemen-crisis-inception-report-august-2021

-

IAHE indicators regarding famine prevention (see Annex 2 in IBID) are quantitative, including: 1) Numbers of people in IPC4 & 5, and trends; 2) Numbers of people provided with access to livelihood assistance; and 3) Evidence of increase or decrease in food consumption and coping strategies.

-

Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen, “Situation of human rights in Yemen, including violations and abuses since September 2014,“ UN Human Rights Council, September 28, 2020, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/GEE-Yemen/2020-09-09-report.pdf

-