Introduction

In the early 20th century Djibouti was a French colony, separated from Yemen by the 32-kilometer Bab al-Mandeb Strait. When the colony needed labor for economic development and the construction of a new port in Djibouti city, they called on Yemeni builders, farmers and sailors. Most workers came from the Tihama region on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast, while the majority of Yemeni merchants trading in Djibouti were from Al-Hujariah, a mountainous region of central Yemen in modern-day Taiz governorate. Today, those who stayed and integrated into society are often referred to as the “Arabs of Djibouti.” Others, mostly merchants from Taiz city and nearby Al-Turbah left their families in Yemen and have maintained a lifestyle of circular mobility.

Many Yemeni refugees who have sought shelter in Djibouti since 2015 had existing links with family or acquaintances already living there. Historically, Yemeni-Djibouti migration has been a form of “chain migration,” a process by which the act of migrating creates social capital, and friends and relatives play a major role for those who follow in their footsteps.[1] Migrant flows are also deeply intertwined with the relationship and level of interdependence between the departure and arrival territories. Yemenis arriving in Djibouti as refugees of war differ significantly from those who came during earlier waves of chain migration: refugees are granted special legal status and typically have fewer material resources or opportunities to integrate socially and professionally. This leads them to have lower social standing, and many are spatially confined to a refugee camp. By granting certain legal freedoms to refugees, the Djiboutian government has attempted to provide them with some means of social mobility, but overall, these policies have failed to address the deeper roots of the problem. For many refugees, the main barrier to socio-economic integration is their exclusion from the established communities of Yemeni migrants and merchants already present in Djibouti.

For 50 years, Djibouti has been a crossroads between Africa and the Middle East, and migrants have both transited and settled there. Following its independence in 1977, Djibouti became a hub for Somali, Ethiopian and Afar Eritrean migrants. Many remained in the small country of 989,115,[2] which faces high rates of poverty[3] and unemployment.[4] The ongoing Yemeni war has prompted a further influx: 19,641 refugees and 11,153 asylum seekers have arrived in the country at the beginning of 2019.[5]

This policy brief aims to trace the evolution of pre-and post-2015 Yemeni migration to Djibouti and its consequences on migrants’ legal rights and socio-economic integration. Fieldwork was carried out in commercial areas of Djibouti city and in the Markazi camp located near Obock, on the north coast of Djibouti. Additionally, a six-month ethnographic qualitative investigation was undertaken in Djibouti between 2019 and 2021. About fifty interviews were conducted with Yemeni men and women, their families and aid organization representatives. A brief profile of the interviewees mentioned in the paper is provided in Appendix A. Open-source intelligence and qualitative and quantitative methods were also employed to understand how Yemeni refugees access services and derive their livelihoods. Data collected during fieldwork gives a picture of Yemenis’ integration into economic and social life. Data was collected during interviews and formal and informal interactions with refugees and administration staff at the Markazi camp. In the field, direct and indirect techniques of observation were utilized by researchers to conduct their analysis.

The first section of this paper describes the different migration patterns of Yemenis to Djibouti from the beginning of the 20th century. The second section examines the legal status of Yemeni migrants. It also describes the reception policies implemented by Djibouti in various political contexts during its history. The third section focuses on a comparison between the socio-economic integration of Yemeni merchants in the capital city and Yemeni refugees registered in the coastal town of Obock. Finally, recommendations are presented to policy-makers in the Djiboutian government for legislation on access to rights and the harmonization of legal statuses, and to organizations for projects that can contribute to the socio-economic integration of refugees and fill current gaps in the response.

Yemeni Migration to Djibouti in Context

Historical Migration: Arabs of Djibouti and the Taizi-Yemeni Merchants

From 1862 to 1896, the port of Obock and French expansion throughout the Somali Coast attracted many workers and merchants from Yemen. French subjects living in the vicinity of the future capital of Djibouti were nomadic — unfamiliar with construction, agriculture and maritime trade. The vast majority of Yemeni workers who filled these jobs came from the coastal Tihama region via the ports of Mokha and Dhubab. They settled in the southern part of Djibouti city, the Wadi of Ambouli. Some Yemenis merchants from Hadramawt, Aden and Sana’a lived in the northern part of Djibouti city known as Djibouti fawq (Upper Djibouti)[6] but the majority of small merchants engaged in retail trade were from Taiz city and Al-Turbah in modern-day Taiz governorate.[7] By 1927, 45 percent of the population of Djibouti city was of Yemeni origin and owned nearly 90 percent of the shops and 80 percent of the buildings.[8]

Ganna,[9] a Yemeni immigrant who was raised in Djibouti and conducted research on the history of Yemenis in the country, described three distinct historical communities: one in fawq, another in Ambouli and a third group of itinerant merchants:

- Yemenis who settled in Djibouti fawq

Yemenis in Djibouti fawq, have been living and working alongside the French and other foreigners settling in Djibouti. According to Ganna, Yemenis in fawq have assimilated in Djibouti. Two members of the Arab community of Djibouti also stated that members of their community have lost many of their historical cultural practices (dress, art, crafts, cooking and language) and identities, including their tribal affiliations and links to Yemen.

- Yemenis who settled in Ambouli

Yemeni migrants in Ambouli have retained part of their historical identity, as their spatial and social marginalization has led them to retain Yemeni cultural and linguistic practices, such as those studied by the linguist Souad Kassim Mohamed. Mohamed notes that more recently, Ambouli Yemenis have taken a form of “social revenge,” studying French to become officials and landowners.[10]

- Yemeni merchants in Djibouti

From the 1950s, life in the mountains of Taiz became increasingly difficult, and many breadwinners decided to try their luck becoming merchants in Yemeni cities and neighboring countries such as Saudi Arabia and Djibouti.[11] They wanted to earn money to improve their living conditions, marry, buy land and build houses.[12] Migration chains from villages in Taiz to East Africa and Djibouti formed. Merchants then moved back and forth. Most were born and raised in Yemen and married there, and traveled between the two shores of the Red Sea for work. After collecting enough money in Djibouti, they invested in real estate in Yemen, where they returned to retire, passing their trade and business to their sons. Wives and children did not move from Yemen, in order to preserve traders’ connections with their home country.

A large part of the merchant community self-segregated by sending their children to Yemeni or Arab schools, using the Taizi-Yemeni dialect and practicing the strict division of space according to sex, with women wearing the litham to cover their face.[13]

Most members of the Yemeni merchant community do not possess Djiboutian nationality. They deny the long-term nature of their migration, which the sociologist Abdelmalek Sayad calls the “illusion of the temporary.”[14] Many have not applied for Djiboutian nationality, as they enjoy a high level of mobility under their legal status of “foreign worker.” Aisha, a 50-year-old woman, explained that before the war in Yemen, anyone who applied for Djiboutian nationality was shamed by other members of the community as a fool, or “betrayer.” She added of Djiboutian nationality: “we don’t want it,” and “we piss on it!” In addition, naturalization was described by her and many other interviewees as being very difficult to obtain for the few Yemenis who sought it. After living in Djibouti for 30 years, Aisha said she still does not have Djiboutian nationality.

Changes and Continuities in Yemeni Migration Patterns

Yemeni migration to Djibouti has fluctuated according to political and economic developments in both countries.[15] Notable waves occurred during French colonization and development of Djibouti in the early 20th century, with the return of Yemenis back to their country following Djibouti’s independence in 1977 and with the commercial migration from central Yemen to Djibouti during the Yemeni rural exodus of the 1970s and 1980s. Since 2015, the deterioration of political, economic, social and health conditions in Yemen has pushed many Yemenis to return to Djibouti, a process facilitated by the country’s immigration and refugee policies. Due to its geographic proximity and long-standing tradition of migration, the East African coast has become one of the main destinations for refugees fleeing the conflict. Most refugees who have fled to Djibouti since 2015 are Yemeni men, but women and children from regions of historical migration, such as the Red Sea ports and Taiz governorate, have also made the journey. Some join members of their families who already live in Djibouti, making it difficult to make a clear distinction between voluntary and forced migration, even in the current political context.[16] The Yemeni trading community’s presence in Djibouti is a result of hybrid migration caused by both economic opportunities and the ongoing war. The vast majority of breadwinners, usually men, refer to themselves as merchants (tuggaar) as opposed to refugees (laaj’iin). For instance, when Ahmad was asked if he and his family were refugees, he took offense:

Aḥmad: Ah, no! We are not refugees! We are not poor, like the people in the camp… And we are not new to Djibouti. We were already living here before the war.

The inhabitants of the Markazi camp and the wives of shopkeepers, most of whom arrived in Djibouti after 2015, are more accepting of being categorized as refugees.

Reception and Status of Yemeni Migrants and Refugees

Legal Status of Yemeni Families

Legal, political and socio-economic issues arise from the hybrid nature of Yemeni migration to Djibouti. Given the different migratory trajectories, multiple legal statuses exist within the community and sometimes within the same family. Yemenis in Djibouti can hold one of four legal statuses:

- Residence permit holder, often for professional reasons (muqaimiin);

- Djiboutian national (muwatiniin);

- Undocumented migrant, whether they entered the territory illegally or hold an expired visa;

- Or statutory refugee.

It is difficult to evaluate the number of people living under each status as Djibouti’s population censuses are dated and inaccurate. The National Office for the Assistance to Refugees & Disaster Stricken People (ONARS – Office National d’Assistance aux Réfugiés et Sinistré), a local governmental organization whose purpose is to coordinate national action to protect refugee rights, does not have precise data on Yemenis in Djibouti, and neither does the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The collection of ethnic statistics among nationals is prohibited in Djibouti. What remains are UNHCR figures, which only include statutory refugees.

Members of a single Yemeni family residing in Djibouti may each fall under different legal statuses. This is the case for Aisha, who received a residence permit as a result of her two children holding Djiboutian nationality, while her older brother, Atif, a trader who has lived for 30 years in Djibouti, still holds “foreign worker” status. Ahmad brought his wife to Djibouti, who then changed her status to refugee, as have many women who arrived after 2015. Other merchants’ wives live without a residence permit, believing they do not need one, as they are not working and police checks seldom target Yemeni women. The overwhelming majority of Yemenis living in Djibouti have a “foreign worker” residence permit, which must be renewed annually and is expensive (35,000 Djibouti francs, or about 170 euros). A residency permit is often paid for by an employer. This legal status has the advantage of allowing Yemenis to be part of a chain of migration linked to generational continuity.

Since the implementation of the Yemeni reception policy in 2015, those entering Djibouti have been able to apply for refugee status, which offers a number of advantages: it is easy to obtain, free of charge, allows them to work and gives access to benefits including language training, food and financial support.

Those who have arrived in Djibouti since the outset of the war benefit from a registration procedure referred to as prima facie eligibility which means “at first sight” or “at first glance,”[17] which does not require any individual a priori check. This approach is most often implemented during mass migration influxes in emergency contexts.[18] Consequently, Yemenis do not need to prove that they are being persecuted in order to obtain refugee status. Initially, the criteria for obtaining refugee status from the UNHCR was very flexible: anyone who could prove that they held Yemeni nationality was eligible. In 2019, given the large number of applications from people who had been living in Djibouti for a long time, a second criterion was added: having first arrived in Djibouti after 2015.

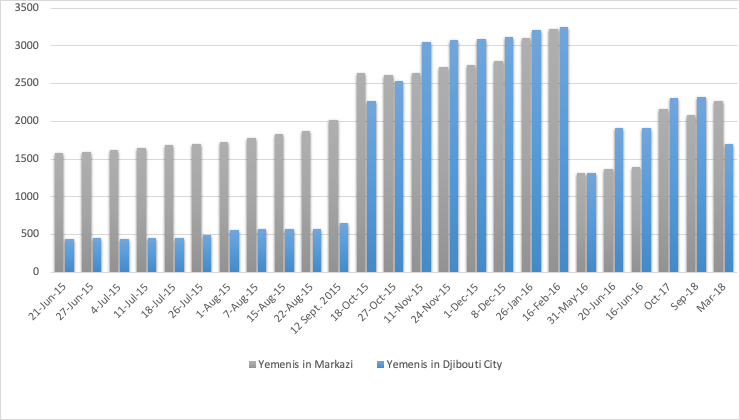

Of the 30,000 migrants who entered Djibouti, the number of registered Yemeni refugees peaked at 7,000. By 2016, this number dropped to 1,400 due to difficult living conditions in Djibouti, particularly in the Markazi camp, which precipitated their return to Yemen.[19] According to the latest UNHCR figures, released in 2019, there were 4,916 Yemeni refugees in Djibouti, with 2,264 registered in the Markazi camp and 2,652 in Djibouti city.[20]

Figure 1. Number of Yemeni refugees in the Markazi camp and Djibouti city

Most migrants living in Djibouti city have a social network comprising family, friends and acquaintances. Those directly integrated into the urban fabric have not experienced the unenviable fate of refugees in the Markazi camp, who depend on multisectoral assistance. The latter wait in the hope of being resettled, or travel back and forth between Obock and the Yemeni coast for work. Yemeni refugees living in the Markazi refugee camp cannot access the capital unless they give up their right to receive governmental and non-governmental aid (housing, food, etc.), and are expected to remain in the camp.

The Markazi Camp and its Demography

Djibouti is both a transit point for migrants from the Horn of Africa who want to reach the Arabian Peninsula for economic reasons and a haven for refugees who choose to settle there.[22] Djibouti is also a focal point for international organizations such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), World Food Programme (WFP), International Organization for Migration (IOM), Danish Refugee Council (DRC), Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and International Children’s Action Network (ICAN). The presence of such organizations facilitates funding and subsidies from Western and Gulf countries and contributes to the economy of Obock city, which hosts migrants from Yemen. The two primary institutional partners that manage the Markazi camp in Obock are local governmental organization ONARS and UNHCR. While ONARS is only one of many agencies that play a key role in the lives of refugees in Djibouti, it remains one of the most important, as all policies concerning refugees are implemented pursuant to its approval and surveillance. Other international and national multi-sector organizations are contracted by UNHCR and ONARS according to their respective roles.

The Markazi camp is located four kilometers southwest of the Obock town center and faces the IOM Voluntary Return Center for Ethiopian Migrants.[23] According to a UNHCR officer, the location was selected to promote employment for host community members and development in Obock.[24] Some members from the host community were able to obtain a shelter in the refugee camp or even register as refugees, so the camp became a place of refuge for the marginalized host community of Afars, who have long been a minority in their own country, and to socially marginalized Yemeni residents.

From 2015 to 2018, Yemeni migrants from the coastal Tihama region made up 60 percent of the camp’s population. According to an interview with an ONARS officer in 2019, individuals from the Tihama made up 90 percent of the camp’s Yemeni population, while the remaining 10 percent were from urban areas, such as Aden, Taiz and Sana’a. Most of the refugees who came from coastal regions are poor fishermen, or muwalladin, an ascriptive classification for people of mixed Arab and other ancestries, notably African. Many of the Yemeni families in the camp are Somali-Yemeni, Ethiopian-Yemeni or even Djibouti-Yemeni.[25] This diversity between locals, urban Yemenis and bi-racial Yemenis plays a role in shaping their social and geographic mobility.

Socio-Economic Integration in Djibouti

Integration of Yemeni Merchants

The value of Yemeni networks becomes evident when comparing the situation of newcomers from villages in Yemen that have historical immigration links versus inhabitants of the Obock refugee camp, who cannot travel to Djibouti city to find work in the trading community, either because they need a sponsor or because they will lose their access to refugee benefits such as food rations and housing. Many of those who have historical links, whether they entered Djibouti after 2015 or earlier, are traders or self-employed in another field. For example, Ahmad, who grew up in Djibouti, went to study in Yemen then returned with his family following the outbreak of the war and got a job in a hardware store run by Yemenis. Most of the husbands of the women interviewed work in trade. Ahmad’s cousin Walid, who arrived from Yemen in the early 2010s, took over a cosmetics shop opened by his father a few years earlier. Some Yemeni migrants opened restaurants, others sold potatoes or chips on the street. However, their lack of linguistic integration limits their professional prospects. Although Arabic is the second official language in Djibouti, French is the language used in education. The language barrier is a hindrance in accessing health care, education and job markets.

In addition, business activities are inaccessible to most Yemeni women due to gender norms regarding the separation of the sexes. The majority of women interviewed grew up in urban areas (Taiz, Al-Turbah, Aden, Ibb or Sana’a), graduated from high school and pursued higher education, unlike their parents. Many of the women met in Djibouti aspire to salaried employment in the service sector. Inaya, a more recent arrival in Djibouti, complained: “I feel that my life has stopped here. I want to study, or work, or anything… But in this country, I can’t.” Salma, a woman in her thirties who arrived in Djibouti six years ago, said she, like many of the Yemenis interviewed, tried to find a job that would suit her, but to no avail. According to her, the reasons were a lack of knowledge of French or Somali, a lack of social capital, her status as a foreign national, the obligation to unveil one’s face and work alongside men in many public and private institutions, her refusal to work in jobs considered humiliating, discrimination and the disapproval of certain families. The few women who do work choose jobs that are normally indoors and require little or no contact with men, such as in offices. Such work may be organized in non-mixed spaces or in fields considered feminine, such as cooking, beauty or education. For instance, Ahlam and Amal are school teachers, and Ganna and Sana are Arabic language teachers. All of them owe their professional success to their earlier migration, which was quite different from that of women who left war-torn Yemen as adults. They arrived in Djibouti as children, in the 1980s and 1990s, which enabled them to obtain Djiboutian nationality, although not all Yemenis born or arrived in Djibouti at a young age have been naturalized.

Integration of Yemeni Refugees in Obock

Unlike the other refugee camps in Djibouti, which are relatively far from the cities, Markazi lies 4km from the Obock city center. As previously explained, Djibouti suffers from a high unemployment rate, but the arrival of refugees was a blessing for the town of Obock and its local population of Afar Ethiopians, who had been forgotten, ignored or abandoned by their own government. Obock was transformed as the arrival of refugees was followed by the establishment of humanitarian aid organizations and funds to support the area and its residents. After the arrival of Yemeni refugees, street lights were installed from the city center to Markazi camp. European Union donations funded the construction of a nearby water tower. The work opportunities in organizations such as UNHCR or NRC are divided between the local population and Yemeni refugees. For example, when a decision was made to remove unoccupied caravans,[26] a group of Yemeni refugees and locals were paid to do the dismantling. When the refugees and locals were asked about the process, they said there is a rule for every project implemented in the camp: if the Yemenis benefit, the locals must benefit as well.

Humanitarian funding is largely oriented toward short-term projects characterized by the physical delivery of aid (such as food distribution). Aid organizations identify refugees as beneficiaries, not as decision-makers or evaluators. Refugees were rarely meaningfully involved in discussions about the best use of resources.

Given that only a small percentage of Yemeni refugees were included in the economy of the camp, some have tried to use other means to secure their livelihoods. Some are forced to sell their household items, clothing or part of the food rations they receive from aid workers. Some men return to work for a few months in Yemen and send money back to their families in the camp. Adolescents in Markazi wait for their summer vacation period to travel to Djibouti city for day labor. Other common types of labor undertaken by Yemeni refugees include:

- Fishing: Employment opportunities are limited in Obock and neighboring Tadjoura city, so most Yemeni refugees are in the fishing and domestic service sectors. Although refugees are prohibited from obtaining fishing licenses (as a common practice and not by law), some work as fishermen under a Djibouti national and others fish in the sea adjacent to the camp.

- Employees of organizations: Refugee employees in organizations are either permanent employees or hired for a specific task within the camp. They are not allowed to be paid more than $250 per month per Djiboutian government regulations. Day laborers are hired as needed for the camp. For example, the NRC-led dismantling activity of unoccupied shelters (tents and caravans) in the camp was carried out by refugees and locals, who were paid based on the number of structures they dismantled.

- Selling products: Yemeni refugees trade what they have in order to get what they need. It is common for an emergency food package received by a family to be traded or sold by refugees to locals/host community members in the city center, in order to use the money to access locally available food items. Many are forced to reduce their food consumption and sell food rations to cover non-food items not included in the aid package.

Conclusion

The hybrid nature of Yemeni migration patterns is historically rooted in labor migrations and deeply linked to the war in Yemen. There are variations in legal status, material and humanitarian situation and socio-professional integration between those who arrived through chain migration and those who have no family or community roots in Djibouti, which cause inequalities between Yemeni migrants in the capital city and Yemenis in the refugee camp. Djibouti’s reception policy toward Yemen provides new resources, particularly in legal terms, but the issue of socio-economic integration remains unsolved, especially for those who do not rely on the resources of the trading community. This emphasizes the importance of considering the history of Yemeni migration to Djibouti in order to respond in the most relevant way to the questions posed by post-2015 migration.

Policy Recommendations

To the Djiboutian Government:

- Conduct a mapping and a baseline study on existent laws on the refugees’ access to rights, in order to measure the gap between the present laws that are supposed to protect them and the lack of application and reinforcement.

- Address the absence of legislation concerning the harmonization of legal statuses within a family.

- Guarantee the right of movement to refugees in the Markazi camp by allowing them to travel to Djibouti city to integrate socially and professionally and network with the existing Yemeni community.

- Enable access to fishing licenses for Yemeni fishermen to avoid pushing them into illicit activities, the underground economy or to return to Yemen in order to bring goods back to Djibouti.

To International Organizations:

- Reinforce socio-economic integration and cooperation between locals and refugees by involving refugees and locals in the process of developing projects and reducing institutionalized exclusion by including them in the decision-making process (especially women)

- Reduce aid dependency (such as food rations and temporary jobs) by supporting local businesses and entrepreneurship, such as innovative agricultural methods for farming in arid areas.

- Promote direct investment in the form of micro-credits and professional development counseling.

- Provide the necessary tools to render individuals independent, such as sewing machines.

- Implement Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) for youth and adults on various potential trades, so refugees can choose training for trades they are eager to pursue.

Appendix A: Select interviews conducted between 2018 and 2021 in Djibouti

Mustafa: A Djiboutian Arab of Yemeni origin, aged about sixty, he holds a prestigious position in the Djiboutian administration. He also presides over an association that helps disadvantaged people, in particular Djibouti Arabs of Yemeni origin and, more recently, Yemeni refugees, to whom the association provides financial, material, food and medical assistance. He was interviewed for one hour on the premises of the association in January 2019.

Aya: A Djiboutian Arab of Yemeni origin belonging to the Ambouli community, she is a multipurpose employee in a Yemeni NGO established in Djibouti following the arrival of Yemeni war refugees. One of the authors met with Aya for a 1.5-hour interview at the association’s offices in January 2019, where she presented the association’s activities, saw her regularly in 2020 and 2021, and was invited to her home, within the Arab community of Ambouli.

Ganna: She is in her forties. She arrived in Djibouti at a young age, where her father was a shopkeeper in Djibouti city. She works as an Arabic teacher and conducted research on Arabs and Yemenis in Djibouti during her studies.

Aisha: Aged about fifty, Aisha was born and raised in a village in Taiz’s Al-Hujariah region. At 14, she married her cousin Nabīl, a merchant, and went to live with him in Djibouti. Their two sons, Ahmad and Basheer, grew up there. In the early 2000s, the family returned to Yemen. At the beginning of the war, Nabil was killed in a land dispute and his widow and sons returned to Djibouti city. She owns apartments and commercial premises that she rents out.

Ahmad: Aisha’s eldest son, in his thirties. He studied engineering and is married to Iman, the daughter of Aisha’s sister. They have three children together. He works for a foreign company.

Basheer: Aisha’s youngest son, age 30. Married and a father of two. Born in Djibouti, he moved to Yemen, then to the United States and finally to Europe.

Atif: Aisha’s brother. He is in his fifties and has been living in Djibouti for 25–30 years. A merchant, he runs two shops in Djibouti fawq with his sons. His wife stayed in Yemen with their daughters.

Khadiga: In her twenties, from a village near Taiz. Mother of four. In Djibouti for eight years, she joined her merchant husband and does not work.

Iman: About 30 years old, Iman is Aisha’s niece. She was born and raised in Taiz and Aden. She studied Islamic education and then married her cousin Ahmad. After the beginning of the war, she joined him in Djibouti. Together they have three children and live in Djibouti city. She does not currently work but taught classes when she arrived in Djibouti.

Fahima: Aged about 20, Fahima grew up in Taiz. She married a young Yemeni trader and moved with him to Djibouti in 2020. They have one child. She studies French and does not work.

Inaya: In her thirties, Inaya was born and raised in Al-Turbah. After studying business, she married Aisha’s nephew, who owned a store in Djibouti. In 2017, she joined him for two years in Djibouti city but returned to Yemen in 2019.

Salma: In her thirties. She came to join her husband with her children six years ago and has three children. She does not work, which weighs heavily on her.

This policy brief is part of a series of publications, produced by the Sana’a Center and funded by the Government of the Kingdom of Sweden, examining Yemeni diaspora communities.

- John S. and Leatrice D. MacDonald, “Chain Migration, Ethnic Neighborhood Formation and Social Networks,” The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, vol. 42, no. 1, [Milbank Memorial Fund, Wiley], 1964, pp. 82–97.

- “Statistical Yearbook 2021 Edition [FR],” Institut de la Statistique de Djibouti, 2021, http://www.instad.dj/assets/doc/Annuaire_Statistique_2021.pdf

- “2020 Human Development Report [FR],” United Nations Development Programme, 2020, https://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/fr/DJI.pdf

- “Statistical Yearbook 2021 Edition [FR],” Institut de la Statistique de Djibouti, 2021, http://www.instad.dj/assets/doc/Annuaire_Statistique_2021.pdf

- “Djibouti Fact Sheet,” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, January 2019, https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/UNHCR Djibouti Fact Sheet – January 2019.pdf

- Alain Rouaud, “A History of the Djibouti Arabs (1896-1977) [FR],” Cahiers d’Études Africaines, vol. 37, no. 146, 1997, pp. 319–48.

- Alain Rouaud, “A History of the Djibouti Arabs (1896-1977) [FR],” Cahiers d’Études Africaines, vol. 37, no. 146, 1997, pp. 319–48.

- Alain Rouaud, “General introduction to a monographic study of the Yemeni community in Djibouti [FR],” (Paris : Inalco, 1980), p. 159.

- A description of all interviewees mentioned in-text can be found in Appendix A.

- Souad Kassim Mohamed, “Description of the Hakmi language of Djibouti. Vernacular Arabic of the capital [FR],” PhD thesis in Language Sciences, (Paris, Inalco, 2012)

- Roman Stadnicki, “Yemenis in urban transition [FR],” in Laurent Bonnefoy, “Yemen: The Revolutionary Shift [FR], (Paris : Karthala, 2012) pp. 201-224.

- Nora Ann Colton, “Homeward Bound: Yemeni Return Migration,” International Migration Review, vol. 27, no. 4, 1993, pp. 870-882.

- Morgann Barbara Pernot, “To be Yemeni, to remain Yemeni. The territories of the feminine entre-soi among Yemenis in Djibouti [FR],” Masters Thesis in Sociology, (Paris, Sciences Po, Inalco, 2020)

- Abdelmalek Sayad, “Immigration, or the paradoxes of alterity [FR],” (Louvain-la-Neuve, De Boeck Université, 1992), p. 331.

- Samson A. Bezabeh, “Subjects of Empires/Citizens of States: Yemenis in Djibouti and Ethiopia,” (Cairo : The American University in Cairo Press, 2019), p. 252.

- Seteney Shami, “The Social Implications of Population Displacement and Resettlement: An Overview with a Focus on the Arab Middle East,” International Migration Review, 27 (101), 1993, pp. 4-33.

- “Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status and Guidelines on International Protection Under the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees,” UNHCR, 2011, https://www.refworld.org/docid/5cb474b27.html

- “UNHCR Guidelines on the Application in Mass Influx Situations of the Exclusion Clauses of Article 1F of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees,” UNHCR, 2006, https://www.refworld.org/docid/43f48c0b4.html

- “Djibouti UNHCR Factsheet,” UNHCR, 2016, https://reliefweb.int/report/djibouti/djibouti-factsheet-january-march-2016

- “Djibouti UNHCR Factsheet,” UNHCR, 2019, https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/UNHCR Djibouti Fact Sheet – January 2019.pdf

- UNHCR, “Djibouti: inter-agency update for the response to the Yemeni situation” 1-50 https://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain?page=search&skip=0&query=inter-agency&coi=DJI

- Nelly Fualdes, “Crisis in Yemen: How Djibouti became a haven for refugees [FR],” Jeune Afrique, 2019, https://www.jeuneafrique.com/mag/715466/societe/crise-au-yemen-comment-djibouti-est-devenu-un-havre-pour-les-refugies/

- “Emergency Plan of Action Djibouti: Yemeni Refugees.” IFRC, 2015, https://reliefweb.int/report/djibouti/djibouti-yemeni-refugees-emergency-plan-action-epoa-operation-n-mdrdj0

- Emeline Wuilbercq & Emilienne Malfatto, “In the camps of Djibouti, the forgotten refugees following the war in Yemen [FR]” Le Monde, March 25, 2017 https://www.lemonde.fr/proche-orient/article/2017/03/25/dans-les-camps-de-djibouti-les-refugies-perdus-de-la-guerre-au-yemen_5100739_3218.html

- Nathalie Peutz, “‘The fault of our grandfathers’: Yemen’s third-generation migrants seeking refuge from displacement,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 51, 3, 2019.

- The camp is very heterogeneous in its type of shelters. It has 300 prefabricated units provided by the King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Center, Refugee Housing Units (referred to as caravans by the camp inhabitants) provided by the UNHCR and a diverse array of tents provided by different entities. Most caravans and tents were abandoned due to their destruction by the seasonal khamsin winds. After fabrication of prefabricated units, the refugees and members of the host community were paid to dismantle caravans and tents.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية