Executive Summary

Yemen’s social protection system is failing to support its population adequately. Years of conflict have left millions vulnerable, struggling with poverty, hunger, and displacement. This is due to two main issues: a fragmented structure lacking a central governing body and chronic funding instability. These problems lead to a cascade of negative consequences.

Firstly, the fragmented system creates inefficiencies, unequal resource distribution, and unclear accountability. Decades of conflict and economic hardship have created a complex web of vulnerabilities among the population, yet the current social safety net is inadequate. Outdated targeting mechanisms and insufficient needs assessments exclude deserving beneficiaries, while weak monitoring and evaluation methods fail to capture program impact and hinder improvement efforts. Existing programs primarily address immediate needs, neglecting long-term solutions and interventions that could empower individuals and build resilience.

Secondly, the system suffers from chronic funding instability. Reliance on fluctuating international support and resource diversion for other purposes threaten program sustainability. Additionally, systemic weaknesses like staffing shortages, inadequate data management, and limited expertise within institutions further hinder program delivery. Outdated partnerships with UN agencies lack transparency and fail to prioritize the needs of beneficiaries.

However, there is hope. By implementing a series of reforms, Yemen can build a unified, resilient, and sustainable social protection system. Primary recommendations include: establishing a Technical Advisory Panel (TAP) to bridge the fragmented Social Protection Consultative Committee (SPCC); developing a comprehensive national social protection strategy; and strengthening institutions with transparent evaluations and capacity-building programs. Additionally, securing a strong financial commitment from the Yemeni government, exploring diversified funding sources, and strengthening social insurance and microfinance systems are all crucial steps toward a more effective social safety net. By addressing these challenges, Yemen can create a system that truly supports its most vulnerable populations.

Introduction

Social protection is subject to a tangled web of definitions and interpretations. At its core, it encompasses a network of policies, programs, and initiatives to tackle individual and family vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities often arise from necessities like food, shelter, healthcare, and education slipping out of reach. While the UN Research Institute for Social Development[1] views social protection as addressing individual vulnerabilities, and ESCWA focuses on ensuring basic needs across life cycles,[2] its impact resonates far wider. Social protection sits at the heart of inclusive development, holding the key to several Sustainable Development Goals and paving the way for a world free from poverty, hunger, and inequality.[3]

Though specific policies and programs may differ by location and over time, social protection has a universal set of goals. Its core objective is to empower vulnerable groups by reducing poverty and vulnerability and ensuring access to basic needs. But it goes beyond mere survival. By investing in human capital through healthcare and skills development, social protection enhances productivity and economic security for individuals and families. This, in turn, creates a more productive workforce and fosters greater equality across society. Social protection can function as a comprehensive system, weaving policies, legislation, and interventions to uphold human rights, ensure equal access, and create a social safety net. In this way, it can serve as a vital force for a fairer, brighter future.

This paper argues for reforging Yemen’s existing social protection programs into a robust system that protects against unacceptable hardships and insecurity. It proposes a systems approach predicated upon coherence between programs, coordination between institutions, shared administrative systems, and efficient allocation of financial resources to address the diverse needs and risks faced by different segments of the population, ensuring no one is left behind. Reforms should be guided by a comprehensive, forward-looking analysis that takes a holistic approach, encompassing demographics, economic outlook, poverty dynamics, labor market trends, gender inequalities, and environmental vulnerabilities. The reform strategy must consider current and future challenges to develop effective interventions. The initiative should serve multiple functions, including protective, preventive, and promotive, and be conducted progressively through a practical, phased approach.

Background

Yemen’s Social and Economic Context

Yemen’s nine-year conflict has created one of the world’s worst man-made humanitarian crises.[4] The economic impact has been devastating: GDP plummeted over US$126 billion between 2015 and 2020.[5] Over 18 million people need humanitarian assistance and protection services in 2024. People are suffering from the compounded effects of violence, ongoing financial crisis, and disrupted public services.[6] The average Yemeni’s income has shrunk by nearly 70 percent since 2014,[7] pushing more and more into poverty. Based on a 2022 estimate, Yemen’s poverty rate was a staggering 74 percent and could remain between 62 to 74 percent by 2030, further deepening the crisis if the conflict persists.[8] Unemployment rates were high even before the conflict escalated, reaching 32 percent in 2014.[9] Families struggle to put food on the table, with nearly 60 percent of the population facing food insecurity as of March 2022.[10] This food insecurity translates into devastating health consequences, with millions of children and pregnant women suffering from acute malnutrition. The conflict has also displaced 4.56 million people within Yemen, further exacerbating the humanitarian crisis.[11]

Yemen’s public services have crumbled under the weight of war. Necessities like electricity, healthcare, and education are now precarious luxuries for most. A staggering 49 percent of the population does not have access to enough drinking water, and 50 percent of hospitals are fully or partially functioning. This leaves them vulnerable to illness, hunger, and despair. Compounding this hardship, nearly 90 percent lack access to publicly supplied electricity.[12] A generation’s future hangs in the balance, with almost 2.7 million children denied the right to education.[13] This tragic erosion of vital services is evident in Yemen’s plummeting human development ranking, from 160th in 2014 to 183rd in 2023,[14] a stark reflection of the conflict’s devastating impact.

Social Protection in Yemen

Social protection services remain a vital lifeline for countless Yemenis, and their importance has grown exponentially over time. Conflict, war, and their devastating economic and social consequences have plunged large swathes of the population into deeper vulnerability. Added to this are the profound impacts of climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic. These crises have further eroded livelihoods, access to resources and markets, and essential services, leaving many struggling for survival. In this bleak landscape, social protection services stand as a beacon of hope, offering crucial support and a path toward resilience for millions.

Following the unification of Yemen in 1990, a comprehensive, formal social protection system was largely absent. While social insurance existed for government employees and some private sector workers, the broader population relied on indirect support mechanisms embedded within the state budget. These included subsidies for basic commodities, fuel derivatives, and essential services like electricity and water. Despite significant financial allocations, the impact of this support was limited. Benefits often reached both the poor and the wealthy, disproportionately favoring the latter due to inherent inefficiencies. At some stages, fuel subsidies were among Yemen’s few widely available social goods. These subsidies keep down the cost of transport, water, and food while supporting local industry.[15]

In March 1995, the Yemeni government, backed by the IMF and World Bank, embarked on a five-year economic and financial reform program.[16] The program’s pillars included drastic cuts to commodity subsidies, partial reductions in fuel subsidies and essential services, and devaluation of the national currency. While aiming for long-term stability, these measures had harsh, immediate consequences. Many Yemenis, particularly low-income groups and government employees, faced significant hardship. Poverty rates soared, reaching 41.8 percent by 1998,[17] as countless individuals were driven into economic vulnerability.

Concerned by rising poverty, the government established the first formal social safety net in 2000. This initiative aimed to counter the negative impacts of economic reforms and protect vulnerable populations. The multifaceted social safety net offered immediate financial relief through direct cash subsidies while simultaneously improving lives and creating opportunities through investment in physical and social infrastructure in deprived areas. Job creation took center stage through projects and programs, especially the fostering of small-scale initiatives that generated income. Significantly, economic empowerment was tackled by developing micro-financing mechanisms, supporting agriculture and fishing, and ensuring equitable access to resources, markets, and funding for disadvantaged individuals and groups. This comprehensive approach aimed to break the cycle of poverty and build resilience within vulnerable communities.[18]

In 2006, Yemen’s approach to poverty evolved. The National Strategy for Poverty Alleviation was woven into the Third Development Plan (2006-2010), shifting focus from resource deficits to a comprehensive understanding of poverty’s causes, characteristics, and impact. This new perspective encompassed education, health, housing, and participation – all facets of human development. Similarly, the Transitional Program for Stabilization and Development (TPSD) 2012-2014[19] aimed to expand social safety nets across Yemen. While the program’s effectiveness has not been evaluated, its goals were clear: to reduce poverty and unemployment. The TPSD planned to achieve this by strengthening social programs, increasing the number of people who benefit from them, addressing issues like education and health, and supporting youth programs and women’s empowerment.

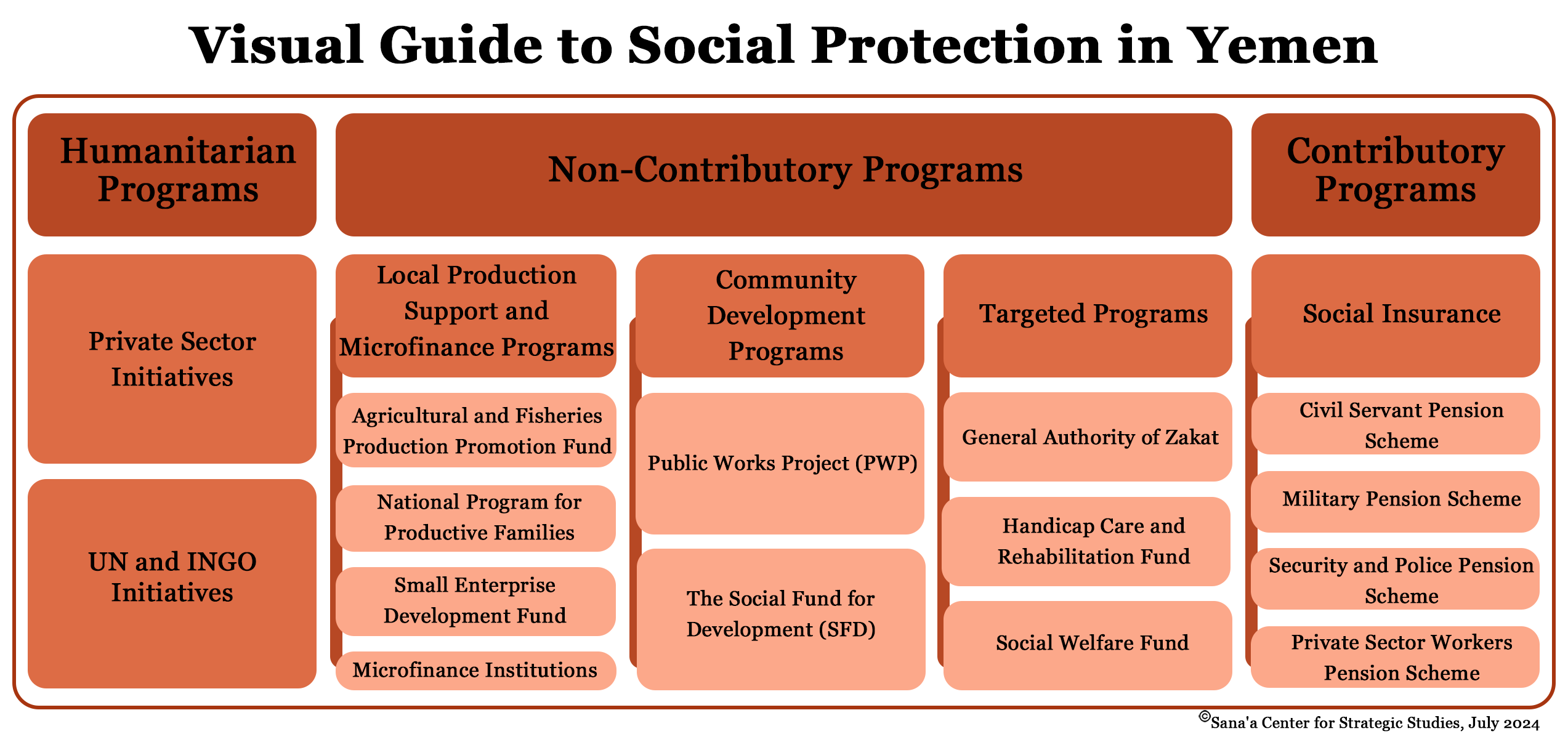

Before the 2014 conflict, Yemen implemented different social protection programs delivered by national institutions. These programs tackled diverse needs, supporting various vulnerable groups nationwide. These programs covered both contributory and non-contributory social protection. While contributory insurance covered public sectors with pensions, non-contributory programs covered other initiatives, i.e., social transfers, social development, targeted protection programs, grants, and local production. The final protection component was humanitarian protection.

Yemen’s contributory social insurance programs continue to offer crucial support for some citizens. They cover the civil, military, and security sectors and provide retirement pensions and emergency compensation. Yemen currently has four separate pension schemes: one for civil servants and public sector employees; a military pension scheme; a scheme for security and police personnel; and another for workers in the formal private sector. However, these services fall far short of public needs. Despite mandatory contributions from employees and employers, only 2.8 percent of the population benefited in 2020, in contrast to the regional average of 30.6 percent and the global average of 46.9 percent. This limited coverage was further hampered by late adoption in the private sector; as of 2016, only around 90,000 private sector workers were insured, representing just 3.7 percent of the workforce.[20]

Yemen’s non-contributory programs[21] are a multifaceted safety net that extends beyond contributory insurance, offering diverse programs for vulnerable populations. Targeted programs include the Social Welfare Fund (SWF), which offers direct cash and in-kind support to orphans, women, disabled individuals, and the impoverished. Established in 1996, the SWF relied on the postal system to deliver cash assistance to 1.5 million beneficiaries. In 2014, cash transfers under the SWF were provided to 29.1 percent of the population, an increase from 12.4 percent in 2005.[22] The outbreak of conflict in 2015 disrupted operations and threatened the well-being of vulnerable populations. With funding from the World Bank’s Emergency Cash Transfers (ECT) program, UNICEF stepped in to fill the gap from 2017.[23] Building on the existing framework of the SWF, the program adjusted to accommodate the changing situation, diversifying delivery channels to include banks and microfinance institutions. Despite the large number of beneficiaries the SWF reaches with cash assistance, its impact is limited due to the amounts it disburses, targeting errors (both of inclusion and exclusion), and the weakness of delivery, grievance redress, and monitoring systems.[24]

Yemen’s targeted protection programs include the Handicap Care and Relief Fund (HCRF), which champions the needs of people with disabilities, employing resources, collaboration, and advocacy to pave the way for education, training, rehabilitation, and economic empowerment. The Martyrs’ Fund provides similar support for the families of soldiers killed in action. Most pension payments have now been suspended due to depleted funding, including government bonds and employee contributions.[25]

Other social protection services are provided by local initiatives set up by the General Authority for Zakat.[26] Zakat, a type of Muslim charitable contribution, plays a significant role in Yemen’s social safety net. Practically, there are two main channels for zakat distribution. The first is the General Authority for Zakat, a government body that collects and pools zakat contributions together and then distributes the funds to those in need. The second is comprised of direct distribution by businesses. Some businesses choose to distribute zakat directly to beneficiaries through various initiatives. These initiatives can provide crucial support, although they reach a very limited number of people. They often focus on specific vulnerable communities and offer direct aid, like food baskets and school supplies. Importantly, some initiatives go beyond immediate needs and launch income-generating projects to empower people for the long term. Currently, zakat funding lacks clear legislative rules and disbursement mechanisms, so the programs it funds have limited impact.[27]

In addition to the above-mentioned safety nets, there are different community development programs that contribute to social protection. Community development programs seek to empower communities and foster long-term well-being. The Social Fund for Development (SFD)[28] tackles poverty head-on through local development initiatives, equipping people with skills, creating jobs, and offering temporary work opportunities. The Public Works Project (PWP)[29] bridges gaps in the provision of essential services, like access to water and sanitation, while boosting economic and environmental well-being in underprivileged areas. These vital programs provide immediate relief and investment to build resilient communities equipped to thrive in the long run.

Additionally, local production support and microfinance programs extend a lifeline to farmers, fishers, women, and youth through the Agricultural and Fisheries Production Promotion Fund (AFPPF) and the National Program for Productive Families (NPPF). These programs provide financial and in-kind support, empowering these vulnerable populations with the tools to thrive. The Ministry of Industry and Trade established Small Enterprise Development Fund (SEDF) in 2002 to support small and medium enterprises. Microfinance institutions and programs also emerged as a critical lifeline for many Yemenis. Providing access to small loans and financial services empowers individuals and communities with the aim of building resilience, combatting poverty, and creating a brighter future. The SFD’s Small and Micro Enterprise Development Unit (SMEPS) supports 13 microfinance institutions, managing a collective portfolio exceeding 44 billion Yemeni rials.[30] The number of active borrowers increased from about 66,400 in 2010 to about 121,000 in 2014. However, the 2015 conflict decreased the client base to 80,800 active borrowers by June 2023.[31]

In addition to these formal social protection programs, Yemen has received significant external support for its struggling population. The ongoing war has exacerbated the need for assistance, and accordingly, humanitarian programs have flourished, with some integration into existing social protection systems. The role of the UN agencies, NGOs, and local organizations has also increased, providing a lifeline to 80 percent of the population through cash, temporary jobs, and improved services with specific initiatives, including the World Bank’s Emergency Social Protection Enhancement and Covid-19 Response Project (ESPECRP)[32] and the UN/EU’s Strengthening Institutional and Economic Resilience in Yemen (SIERY),[33] and Supporting Resilient Livelihoods, Food Security and Climate Adaptation in Yemen, Joint Programme (ERRY)[34] projects, and the provision of services and food aid through the private sector-led Food and Medicine Bank initiative.

Gaps and Challenges in the Provision of Social Protection

Yemen’s social protection landscape remains fragile and susceptible to shocks. Despite dedicated efforts and program successes, gaps remain in the social protection landscape. Fragmented programs, stitched together like a patchwork quilt, lack a unifying vision[35] and leave substantial holes in coverage for the most vulnerable. This fragmented approach significantly undermines the system’s effectiveness, offering limited safety nets in the face of immense hardship. Below are some of the identified gaps and challenges.

A Fragmented System

The social protection system involves diverse actors from government ministries, led by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor, along with specialized funds, international organizations, NGOs, and even the private sector.[36] Despite this collaboration, a central governing body is absent, hindering the system’s effectiveness. This lack of unity leads to inefficient resource allocation, disjointed program implementation, and unclear accountability. This fragmentation significantly undermines the system’s potential to alleviate suffering and promote development.[37] Efforts to establish a unified framework dating back to 2017 resulted in the establishment of the Social Protection Consultative Committee (SPCC). The committee was able to bring together public social protection entities and the private sector but fractured due to the ongoing conflict. A unified framework is crucial to improve efficiency, equity, and accountability, ultimately leading to better outcomes for vulnerable Yemenis.

Deepening Vulnerabilities

Decades of weak economic infrastructure, chronic poverty, and widespread unemployment have created a complex web of vulnerabilities in Yemen. From child malnutrition and food insecurity to limited access to healthcare and education, diverse threats impact individuals across all stages of life. This fragile situation has been significantly worsened by the ongoing conflict. An estimated three-quarters of the population now lives in poverty,[38] with millions facing additional hardships like displacement, malnutrition, disability, and workforce layoffs in the private sector. Addressing these critical needs requires substantial resources and a robust social protection system to help Yemenis weather this crisis and build a brighter future.

Ineffective Targeting

Yemen’s social protection system struggles with inefficient targeting due to two key issues. First, the lack of a comprehensive needs analysis hinders effective resource allocation and intervention design. Without a clear understanding of the specific vulnerabilities across different demographics and potential hazards, it is difficult to target interventions where they are most needed. This is further complicated by weak data and inconsistent economic indicators. Second, outdated targeting mechanisms create significant gaps. Inaccurate and outdated databases, like the pre-conflict Social Welfare Fund lists, systematically exclude deserving beneficiaries, particularly those made vulnerable by the recent conflict. These outdated lists also fail to capture the population shifts caused by displacement and poverty. Regular updates and conflict-sensitive assessments are desperately needed to ensure equitable access to crucial social protection services.

Weak Monitoring and Evaluation Systems

Yemen’s social protection programs lack robust Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) systems, hindering their effectiveness and resource optimization. Weak data and inconsistent economic indicators hamper effective targeting. Traditional M&E mechanisms, often relying solely on financial reports, fail to capture the real impact of programs on beneficiaries’ lives. Furthermore, beneficiaries and local communities are marginalized from M&E processes. This exclusion not only diminishes program accountability but also misses valuable feedback from those directly affected by the programs.

Limited Scope

While various social protection instruments exist, they fall short of comprehensively covering the population’s vulnerabilities and risks; it can be argued that they are ill-equipped to uplift people from poverty. A closer look reveals blind spots in the approach and gaps in addressing the full spectrum of functions. Current programs primarily address immediate short-term needs, which limits their ability to address deeper and longer-term issues of poverty and vulnerability.[39] The reliance on immediate consumption-smoothing through cash transfers neglects crucial promotive and transformative functions, overlooking opportunities to empower individuals and build resilience, and leaving untapped potential for enhancing real incomes, skills, and capabilities.

Chronic Funding Issues

Yemen’s social protection system struggles under the weight of chronic funding instability.[40] Programs like those implemented by the SDF rely heavily on fluctuating international support, leaving them vulnerable to gaps when contributions wane. State resources are often prioritized for military spending, diverting funds from essential services like salary and pension payments.[41] The situation is further exacerbated by rising costs due to inflation coupled with a decrease in donor support. This combination creates a resource squeeze, straining the system’s ability to adequately assist those in need.

Further compounding these challenges are unreliable investment mechanisms within contributory programs, in which insurance funds primarily relied on low-yield cash investments, including treasury and government bonds.[42] Investment was further hampered by a 2023 ban on certain banking practices, jeopardizing the financial stability of these institutions and their ability to fulfill their social mandates. Current cash assistance programs also fall short, providing minimal daily amounts that fail to meet the World Bank’s poverty line.[43] This inadequate support pushes families deeper into hardship.

Additionally, the lack of coordination between implementing agencies leads to duplication of programs in some areas and gaps in essential services in others. This creates an uneven distribution of resources, leaving entire communities vulnerable despite their facing similar crises.[44]

Systemic Weaknesses

The institutional landscape suffers from disarray. A lack of comprehensive capacity assessments[45] has resulted in scattered and poorly coordinated institutions. Staffing shortages and inadequate data management systems plague many organizations, hindering their ability to deliver essential services effectively. Microfinance institutions, particularly non-bank entities, often lack the expertise needed to provide efficient financial and advisory services to micro-entrepreneurs.[46] This limits their potential impact on poverty reduction and economic development.

Existing social insurance institutions face their own set of problems. The current system of social insurance fund management, where senior leadership is appointed by the government, raises concerns about merit-based selection. The lack of a transparent and competitive selection process could potentially lead to the appointment of individuals who lack the necessary experience and expertise and adopt less effective investment strategies. Staffing shortages and limited coordination further hamper their ability to process new pension applications efficiently. Additionally, delayed salary payments and the divided authority between Sana’a and Aden further threaten the rights of beneficiaries.[47] Moreover, the overburdened judicial system delays the resolution of insurance disputes, burdening institutions with high operational costs.

The Social Welfare Fund, with its role restricted due to concerns about operational effectiveness and neutrality, struggles to deliver vital safety nets. Staffing shortages, inadequate data management, and limited funding all hinder its ability to reach vulnerable populations. The social transfer programs also face concerns about projects not aligned with poverty alleviation goals. Examples like the General Authority of Zakat’s Group Marriage initiative raise questions about resource allocation and highlight the need for a clear focus on core priorities of poverty reduction and social safety nets.

Finally, a lack of oversight and accountability surrounding support from UN agencies raises concerns about the effectiveness of international engagement. Outdated beneficiary lists and insufficient technical assistance highlight the need for more transparent and impactful international support.[48]

Conclusion and Recommendations

While Yemen’s social protection system offers crucial support, its effectiveness is hampered by significant challenges. The system lacks a central governing body, leading to inefficiencies, unequal distribution of resources, and unclear accountability. Decades of conflict and economic hardship have created a complex web of vulnerabilities among the population, demanding a more robust social safety net.

Furthermore, outdated targeting mechanisms and inadequate assessments leave deserving beneficiaries excluded. This, coupled with weak monitoring and evaluation methods that fail to capture program impact, hinders efforts to improve the system and incorporate beneficiary feedback. Existing programs primarily focus on addressing immediate needs, neglecting long-term solutions and interventions that could empower individuals and build resilience.

Chronic funding instability due to reliance on fluctuating international support and resource diversion for military spending creates funding gaps that threaten the system’s sustainability. Additionally, systemic weaknesses like staffing shortages, data management issues, and limited expertise within institutions further hinder program delivery. Finally, outdated beneficiary lists and insufficient technical assistance from UN agencies highlight the need for stronger international partnerships built on transparency and beneficiary-centered approaches.

Recommendations for a Unified and Resilient Social Protection System in Yemen

Considering the fragmented nature of the existing SPCC due to the ongoing conflict, the following recommendations aim to establish a unified framework and strengthen the system’s overall effectiveness.[49] If implemented, they would contribute toward building a unified, resilient, and sustainable social protection system that is better equipped to address the needs of vulnerable populations and promote long-term stability and economic security.

Building a Unified Social Protection Framework

- Establishment of a Technical Advisory Panel (TAP): Create a TAP led by a neutral and trusted institution, such as the Social Fund for Development (SFD) due to its established presence and experience. This panel will:

- Facilitate Coordination: Act as a bridge between the two existing SPCCs in Sana’a and Aden, fostering collaboration and knowledge exchange.

- Provide Technical Expertise: Issue technical guidance on program development, implementation, and monitoring.

- Mobilize Resources: Explore and advocate for diversified funding sources, potentially with the support of a donor task force co-led by major investors like the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and the World Bank.

- A National Social Protection Strategy: Develop a comprehensive national strategy with clear goals, target groups, and intervention methods. This strategy should consider:

- Needs Assessment: Conduct a forward-looking national needs assessment to understand evolving poverty trends, vulnerabilities, and social protection triggers.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Integrate inclusive dialogues with all stakeholders, including government agencies, the private sector, civil society, communities, and beneficiaries.

- Existing Capacity: Build upon existing capacities of social protection institutions within Yemen.

- Strengthened Social Protection Institutions: Invest in strengthening social protection institutions through:

- Transparent Evaluations: Conduct regular evaluations of efficiency, independence, and effectiveness.

- Capacity Building: Provide training and resources to equip staff with the necessary skills and knowledge.

- Good Governance: Promote best practices in governance and accountability.

- Program Design and Delivery: Design a framework for effective and affordable program delivery, considering the operational realities in Yemen.

Sustainable Funding and Resource Mobilization

- Diversified Funding Strategies: Explore diverse funding sources to reduce reliance on international aid and ensure long-term sustainability. This could include:

- Fiscal Space Expansion: Identify and implement mechanisms to expand Yemen’s fiscal space.

- International Advocacy: Advocate for international aid that prioritizes domestic capacity building and long-term sustainability.

- Combating Illicit Flows: Address illicit financial flows within the country.

- Government Commitment: Secure a strong financial commitment from the Yemeni government to allocate sufficient resources for social protection programs and review and refocus social transfer programs that are not aligned with poverty alleviation goals.

- Strengthening Social Insurance:

- Legal Review: Review and update legal frameworks to ensure a fair retirement system for public, private, and mixed-sector workers.

- Private Sector Engagement: Provide technical and legal support to the private sector to facilitate their contribution to social security programs.

- Microfinance Support: Create a supportive legal and regulatory framework for microfinance institutions, enabling growth and competition. This can provide vulnerable individuals with access to financial resources and opportunities.

This Yemen International Forum 2023 publication was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, and co-funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the European Union, the Government of the Kingdom of Norway, Open Society Foundations, and the Folke Bernadotte Academy.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. Views expressed within this report should not be construed as representing the Sana’a Center, donors, or partners.

- “Our Impact” Wikipedia, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development,, https://www.unrisd.org/en/about/our-impact

- “Reforming Social Protection Systems,” UN ESCWA, https://www.unescwa.org/reforming-social-protection-systems

- “Building Social Protection Floors,” UNESCAP, https://www.socialprotection-toolbox.org/files/infographics/infographics-spf.pdf

- Andrea Carboni, “Yemen: The World’s Worst Humanitarian Crisis Enters Another Year,” ACLED, February 9, 2018, https://acleddata.com/2018/02/09/yemen-the-worlds-worst-humanitarian-crisis-enters-another-year/

- Taylor Hanna et al., “Assessing the Impact of War in Yemen: Pathways of Recovery,” UNDP, 2021, https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/ye/Impact-of-War-Report-3—QR.pdf

- “Overview of Humanitarian Needs – Yemen,” OCHA, January 2024, https://reliefweb.int/attachments/54baf3f4-a060-4ea3-b36c-c2715d233f79/Yemen Humanitarian Needs Overview 2024 (January 2024).pdf

- “National Accounts,” Yemen Central Statistical Organization (CSO), March 2021, https://cso-ye.org/en/national-accounts/

- “Yemen Poverty and Equity Assessment 2024: Living in Dire Conditions,” World Bank, February 2024, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099030424081530447/pdf/P17919414df5860011a33814c87a62dce86.pdf

- “Labor Force Survey Estimates, 2014,” Yemen Central Statistical Organization (CSO), 2014, https://cso-ye.org/en/labor-force/

- “Yemen: Food Security & Nutrition Snapshot, March 2022,” Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, March 14, 2022, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-food-security-nutrition-snapshot-march-2022-enar?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAjw34qzBhBmEiwAOUQcF4v1994PDJoYkt-agd1QWZ9qLK99R-_Fy4eR69U3gyhHUmtNnBeLLRoCu5wQAvD_BwE

- “Overview of Humanitarian Needs – Yemen,” OCHA, January 2024, https://reliefweb.int/attachments/54baf3f4-a060-4ea3-b36c-c2715d233f79/Yemen Humanitarian Needs Overview 2024 (January 2024).pdf

- Ibid.

- “Yemen crisis,” UNICEF, accessed December 2023, https://www.unicef.org/emergencies/yemen-crisis

- “Human Development Report 2021-22: Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping our Future in a Transforming World,” UNDP, September 8, 2022, https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2021-22

- “Yemen Fuel Subsidy Cut Drives Poorest Deeper into Poverty,” The Guardian, August 26, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/aug/26/yemen-fuel-subsidy-cut-drives-poorest-poverty

- Mansour Ali al-Bashiri, “The Impact of the Economic Stabilization and Structural Adjustment Program on the Private Sector in Yemen,” Sana’a University Master’s thesis, 2010.

- “Household Survey,” Yemen Central Statistical Organization (CSO), 1998.

- “Third Economic and Social Development Plan for Poverty Alleviation 2006-2010,” Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (MoPIC), Sana’a, August 2006.

- “Transitional Program for Stabilization and Development (TPSD) 2012-2014,” Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (MoPIC), September 4-5, 2012, https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/yem161589.pdf

- “Yemen Socio-Economic Update,” Issue 29, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (MoPIC), 2017.

- “Gap Analysis of Yemen’s Social Protection,” Unpublished document by National Social Protection Consultative Committee (SPCC), November 2023.

- Yashodhan Ghorpade and Ali Ammar, “Social Protection at the Humanitarian-Development Nexus: Insights from Yemen,” Discussion Paper No. 2104, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, April 2021, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/606011617773513363/pdf/Insights-from-Yemen.pdf

- “Yemen Emergency Crisis Response Project Fifth Additional Financing (P172662): SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (SIA) For Component 3 (Emergency Cash Transfer),” UNICEF, August 24, 2020, https://www.unicef.org/yemen/reports/yemen-emergency-crisis-response-project “Yemen Emergency Crisis Response Project Fifth Additional Financing (P172662): SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (SIA) For Component 3 (Emergency Cash Transfer),” UNICEF, August 24, 2020, https://www.unicef.org/yemen/reports/yemen-emergency-crisis-response-project

- Ruta Nimkar, et al., “Humanitarian Cash and Social Protection in Yemen,” The CaLP Network, 2021, https://www.calpnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/CaLP-Yemen-Case-Study-WEB-1.pdf

- “Annual Report 2022 [AR],” Public Works Project, https://www.pwpyemen.org/index.php/ar/media-center-2/publications/file/137-annual-report-2022-ar.

- Zakat Newspaper, Issue (29), August 2023.

- Ali Azaki, “ Social Protection and Safety Nets in Yemen,” Institute of Development Studies, December 2015, https://www.ids.ac.uk/download.php?file=files/dmfile/SocialprotectionandsafetynetsinYemen.pdf

- “Republic of Yemen: Social Fund for Development Main Page,” Social Fund for Development, 2024, https://www.sfd-yemen.org/

- “Public Works Department Main Page,” Public Works Department, 2024, https://www.pwpyemen.org/index.php/en/

- “Annual Archive for Loan Portfolio,” SFD-SMED, November 2023, https://smed.sfd-yemen.org/index.php/en/blog-4/aaflp1/477-nov-2023

- “Yemen Socio-Economic Update,” Issue 80, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (MoPIC), 2023.

- “Emergency Social Protection Enhancement and COVID-19 Response Project Main Page,” World Bank Group, 2024, https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P173582

- “Strengthening Institutional and Economic Resilience in Yemen Main Page,” UNDP, 2024, https://www.undp.org/yemen/projects/strengthening-institutional-and-economic-resilience-yemen-siery

- “Supporting Resilient Livelihoods, Food Security and Climate Adaptation in Yemen, Joint Programme Main Page,” UNDP, 2024, https://www.undp.org/yemen/projects/supporting-resilient-livelihoods-food-security-and-climate-adaptation-yemen-joint-programme-erry-iii

- Ali Azaki, “ Social Protection and Safety Nets in Yemen,” Institute of Development Studies, December 2015, https://www.ids.ac.uk/download.php?file=files/dmfile/SocialprotectionandsafetynetsinYemen.pdf

- “Gap Analysis of Yemen’s Social Protection,” Unpublished document by the National Social Protection Consultative Committee (SPCC), November 2023.

- Ruta Nimkar, et al., “Humanitarian Cash and Social Protection in Yemen,” The CaLP Network, 2021, https://www.calpnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/CaLP-Yemen-Case-Study-WEB-1.pdf

- “Yemen Poverty and Equity Assessment 2024: Living in Dire Conditions,” World Bank, February 2024, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099030424081530447/pdf/P17919414df5860011a33814c87a62dce86.pdf

- “Gap Analysis of Yemen’s Social Protection,” Unpublished document by the National Social Protection Consultative Committee (SPCC), November 2023.

- “Yemen Socio-Economic Update,” Issue 29, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (MoPIC), 2017.

- Interview by the authors with a Social Protection Expert, March 4, 2024.

- Muhammad Ahmed Essam, “The Economic and Social Role of Social Insurance Funds in Yemen,” Paper presented at the Yemeni Economic Conference, Yemeni Center for Strategic Studies, Sana’a, October 2010.

- Existing beneficiaries, particularly those enrolled in the SWF program, receive cash aid ranging from 3,000 to 6,000 Yemeni rials. See, “Yemen Socio-Economic Update,” Issue 29, Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (MoPIC), 2017. This is roughly equivalent to US$5.70 – US$11.30 per household per month, translating to a meager US$0.19 – US$0.37 per person per day, far short of the World Bank’s new extreme poverty line of $2.15 per person per day, see “Understanding Poverty Main Page,” The World Bank, 2024, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty

- Clarke P. Knox, “The State of the Humanitarian System (SOHS) 2018,” ALNAP/ODI, https://sohs.alnap.org/previous-editions/sohs-2018

- Ibid.

- Ali Alshebami and V. Rengarajan, “Microfinance Institutions in Yemen ‘Hurdles and Remedies,’” International Journal of Social Work, ISSN 2332-7278, Vol. 4, No. 1, February 6, 2017, https://www.macrothink.org/journal/index.php/ijsw/article/download/10695/8597

- “Retirees in Yemen… Continuous Suffering Due of the Suspension of Pensions [AR],” Alsharq Alaawsat, August 6, 2023, https://aawsat.com/العالم-العربي/4473561-المتقاعدون-في- اليمن-معاناة-مستمرة-بفعل-توقف-المعاشات

- Sarah Vuylsteke, “Rethinking the System: Is Humanitarian Aid What Yemen Needs Most?” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 29, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/reports/humanitarian-aid/15487

- Rwanda’s Social Protection Strategic Plan offers valuable insights for Yemen’s social protection system. Focused on ensuring social protection for all, particularly the vulnerable, Rwanda’s strategy emphasizes income support, social care services, and improved livelihoods. This comprehensive approach can inform Yemen’s efforts to address coverage gaps and strengthen support for vulnerable households. see “Social Protection Strategic Plan, 2018/19-2023/24,” Republic of Rwanda, Ministry of Local Government, 2018, https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/rwa206911.pdf

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية