The Houthi-controlled parliament in Sana’a passed a controversial law banning “usurious transactions” on March 21. Houthi authorities pushed the House of Representatives to prohibit interest-based transactions in Yemen’s banking sector after rejecting amendments proposed by the body’s joint legal committee. The law could have disastrous effects on Yemen’s economy, exacerbating its isolation and deterioration and discouraging investment. Parliamentarians appeared pressured to pass the legislation, with four MPs choosing to withdraw from the session in protest. One MP, Ahmed Saif Hashed, characterized the law as unconstitutional and said it would have catastrophic consequences for banks and the rights of citizens. Both the Minister of Finance and the governor of the Sana’a-based Central Bank of Yemen (CBY-Sana’a) refused to endorse the law publicly and were absent from the parliamentary session. A Sana’a-based banking official told the San’a Center that religious hardliners within the Houthi movement pushed for the legislation to be passed without waiting for the results of a feasibility study, in which experts had reportedly advocated caution and the development of a phased Islamization of the financial system.

The Houthi-controlled Council of Ministers first approved the draft law in September 2022, but it was not ratified by the legislature amid pushback from the Yemeni Banking Association (YBA), economists, private sector actors, and the public at large, who questioned the Islamic jurisprudence upon which the law was based and warned of massive financial fallout should it be enacted. These warnings were renewed ahead of the law’s passage in an eight-page letter to the House of Representatives from the YBA, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Union of Drug Producers, and the Yemeni Industrialists Association. Critics of the law contended that banning interest-based transactions threatens the stability of the local currency and the operations of the banking system, most notably the financing of basic imports. Treasury bills and government bonds that Yemeni banks and pension funds have historically invested in would be banned. A further decrease in liquidity would leave banks even less capable of honoring customer obligations, which would further erode confidence in commercial banking services and jeopardize their financial solvency. The Islamization of the banking sector would also further isolate the Yemeni banking system from the rest of the world, hampering the settlement of payments and the country’s ability to access foreign financing. In the letter, the groups also warned of potential bank runs and increased insecurity if the law were to be passed.

Despite these warnings, on March 27, the Houthi authorities published law No. (4) of 2023 in the Official Gazette. Signed by the head of the Supreme Political Council, Mahdi al-Mashat, the law went into effect on March 22. Its 13 articles rely heavily upon provisions from the Yemeni Civil Law No. (14) of 2002. Articles 1 and 2 define transactions involving interest, including debt securities and treasury bills previously issued by the CBY on behalf of the Ministry of Finance. The third article states that “all forms of usurious transactions in all civil and commercial transactions that take place between natural persons or legal entities shall be prohibited,” and declares all “usurious benefits… absolutely null and void.”

Articles 7 and 9 are the most consequential for the banking sector and its customers. Article 7 prohibits the collection of interest on civil and commercial transactions “due before the date at which the law becomes enforceable and [which] has not yet been performed,” obliging the debtor to repay only the principal. This could provide a legal rationale for denying commercial banks payment of hundreds of billions of Yemeni rials in interest due on public treasury bills since late 2016. Banks say the funds are necessary to pay depositors their accrued interest. However, a banker in Sana’a who spoke with the Sana’a Center said that the interest already calculated on treasury bills and deposited as non-cash balances into the banks’ accounts at the CBY-Sana’a would remain.

Article 9 cancels “all provisions and rules in ratified international laws and agreements that include the permissibility of working with usurious interest.” Interest-based transactions conducted over the global financial system, such as through foreign correspondent banks or any other international entity, would theoretically be banned, and any international agreements that involve interest-based operations could be canceled. The article also defines legal provisions involving usurious transactions that must be changed in other Yemeni laws, including ones governing the CBY and commercial banks. Houthi authorities remain vague on their proposals to set up an alternative financial system, with the last article of the law mentioning that a “good-lending fund” will be established in a forthcoming presidential decree.

On March 27, the day the law was published, Al-Mashat met with officials from the CBY-Sana’a and bank representatives. After the law’s passage, banks in Sana’a reported an increased number of customers seeking to withdraw their deposits. During the meeting, Al-Mashat sought to reassure the sector, saying the deposits of commercial banks and depositors invested in treasury bills before the passing of legislation will be “resolved.” He added that the CBY-Sana’a would develop and issue instructions regarding Sharia-compliant instruments that banks can invest in moving forward, and that it will guarantee merchants and depositors profit on their investments. Al-Mashat also indicated plans to establish a stock market in areas under Houthi control.

The Islamization of the financial system comes as part of Houthi authorities’ national economic plan, issued in 2019, which seeks to revamp regulatory frameworks and the institutional setups of key economic sectors, such as the financial industry. Yemen’s financial sector has traditionally been structured to finance government investment and spending with depositors’ funds. As a result, banks failed to develop modern banking investment tools beyond the public debt market. Given the poor economy and business climate, opportunities for new investment pathways remain limited. Two financial systems will now prevail in Yemen – an interest-based system in Aden and an Islamic finance-oriented one in Sana’a. The split will further deepen the monetary and financial division in the country and complicate how financial institutions operate across Houthi- and government-held areas.

Battle to Control Imports Intensifies

Following the government’s announcement of a package of economic reforms in early January, including a decision to raise the customs exchange rate by 50 percent, from YR500 to YR750 per US$1, there has been widespread criticism against their implementation. Even parties within the government have warned of the reforms’ catastrophic effects on citizens, merchants, and the private sector at large, and the Administrative Court in Aden stepped in to halt the customs hike. Capitalizing on the criticism, Houthi authorities began to pressure commercial importers in early February and offered economic enticements in a bid to redirect commercial shipments to the port of Hudaydah and border crossings under Houthi control.

During the course of March, Houthi authorities have continued to pressure commercial importers to redirect shipments to Houthi-held ports. In a television interview from the port of Hudayah on March 5, Houthi-aligned Minister of Transport Abdelwahab al-Durra reported that the ports of Hudaydah, Salif, and Ras Issa would soon be ready to receive additional traffic. He claimed that 18 ships transporting various commodities and goods were currently on their way to Hudaydah. According to a report published by the Yemen Red Sea Ports Corporation (YRSPC) on March 7, seven ships were docking at the Houthi-held port and eight others were queuing. Eight of the 15 ships were transporting fuel derivatives, four carrying iron rebar, two carrying wood, and one carrying grain and milk.

Previously during the conflict, the port of Hudaydah only received a limited variety of goods, including fuel, rice, wheat, and other food commodities. According to the head of the Houthi-affiliated YRSPC, Mohammed Abu Bakr Ishaq, the United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen (UNVIM) has decided to allow more types of goods to enter Houthi-held ports. The UNVIM team also allegedly agreed to operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to clear ships for entry; previously, UNVIM only worked four days a week. Ishaq also claimed during the March 7 interview that vessels are no longer subject to a second inspection by the Saudi-led coalition and could proceed directly from Djibouti to the port of Hudaydah following UNVIM approval. During the same television interview, Houthi Transport Minister Al-Durra noted Hudaydah’s limited capacity to receive cargo ships, which he blamed on coalition airstrikes on port infrastructure during the war. In a March 6 meeting with United Nations Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen David Gressley, Al-Durra demanded that the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) support infrastructure development projects for the ports of Hudaydah, Salif, and Ras Issa, noting specifically that more bridge cranes were required to receive additional cargo. The UNDP is tasked with providing support to the YRSPC in coordination with relevant governing authorities, the United Nations Mission to Support the Hudaydah Agreement, UNVIM, and the World Food Programme. The government-run Gulf of Aden Ports Corporation has warned against the redirection of imports to Hudaydah, and has threatened to blacklist companies that do so.

Houthis Freeze Yemenia Airways Accounts

In early March, Houthi authorities froze accounts owned by Yemenia Airways at banks operating in areas under their control. The move came after the Houthi-aligned Ministry of Transportation failed to pressure Yemenia’s administration to open flights to additional destinations. On March 8, Houthi-aligned Minister of Transport Al-Durra accused the Saudi-led coalition and the internationally recognized government of intentionally delaying the expansion of flights from Sana’a airport to several destinations, including Egypt and India. Al-Durra also claimed that Yemenia has failed to act impartially and accused its leadership of conspiring to cancel flights to both countries that had previously been approved. As part of the April 2022 truce agreement, Sana’a airport reopened for commercial flights after nearly six years of inactivity. One flight occurred between Cairo and Sana’a in June before the route was halted. Since then, Yemenia has only flown in and out of Amman, Jordan. According to Al-Darra, Yemenia has completed 119 civilian flights to Amman since the route reopened, transporting an estimated 60,000 passengers. Prior to the conflict, approximately 6,000 passengers flew in and out of Sana’a airport each day, transited by Yemenia and other carriers, such as the Emirates, Qatar, and Turkish airlines.

Though Houthi authorities are pressuring Yemenia to expand its list of destinations, transport and security authorities in countries such as Egypt and India have yet to approve flights originating from the Houthi-held capital. Any expansion of flight destinations will likely require a deal with the Saudi-led coalition and/or the government. The targeting of Yemenia Airways’ accounts may be viewed as part of a larger Houthi strategy aimed at pressuring Saudi Arabia to lift restrictions placed on airports, seaports, and land crossings under Houthi control. The account freeze came after the Houthis launched an intensive campaign for pressuring commercial importers to redirect shipments from government-held ports to Hudaydah. On March 8, the head of the Houthi Supreme Political Council, Al-Mashat, threatened military action against the Saudi-led coalition unless the restrictions on Sana’a airport and Hudaydah port were lifted.

Currency

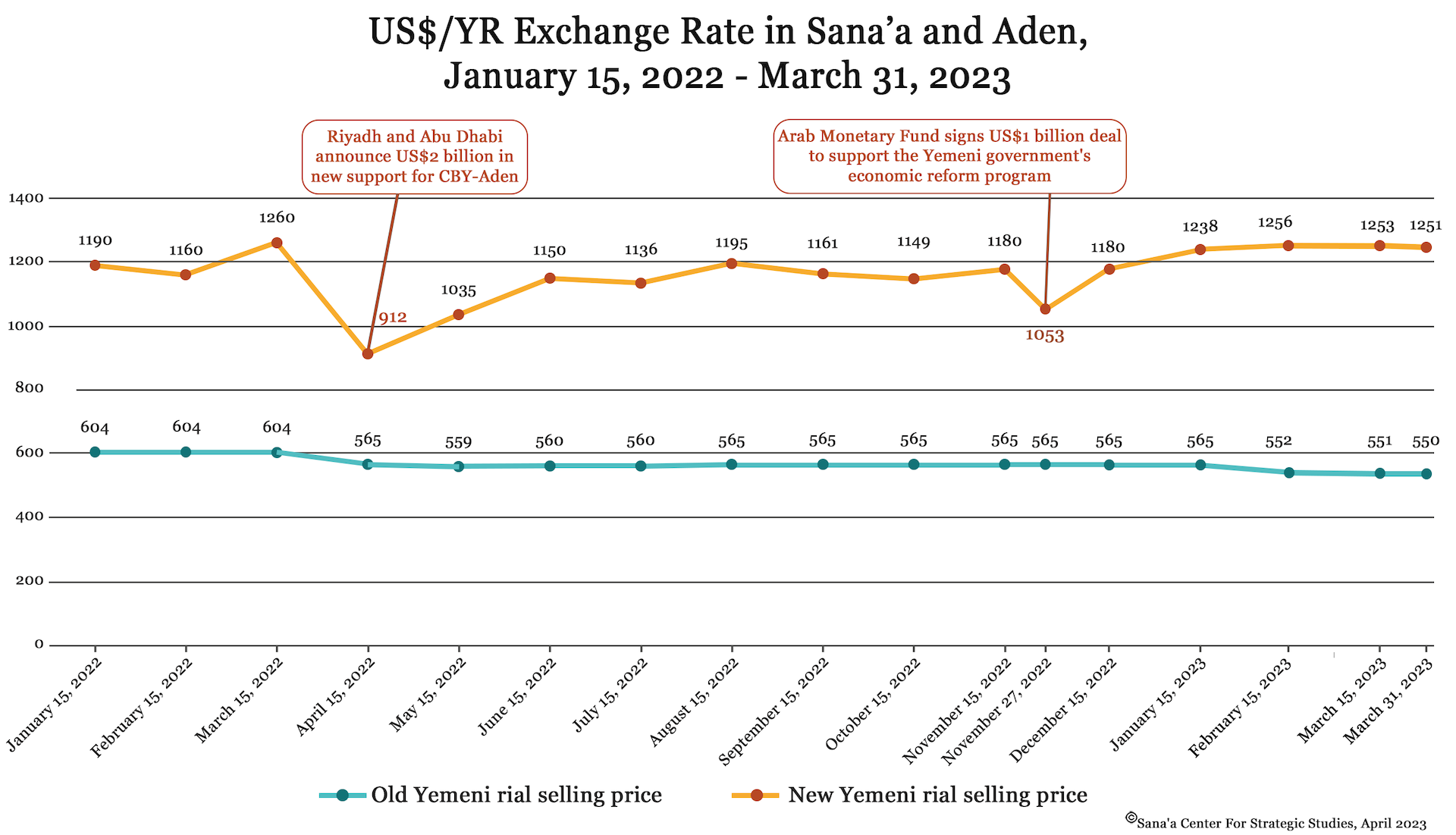

The exchange rate for new rials in government-controlled areas remained stable in March, trading at YR1,252 on average. This relative stability followed the announcement of a US$1 billion Saudi deposit earmarked for the government-run Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden) to replenish its depleted foreign exchange reserves, with the deposit to be mainly handled through the Arab Monetary Fund (AMF). Early in the year, the new rial depreciated by almost 4 percent, from YR1,225 per US$1 on January 1 to YR1,270 as of February 19. It then regained value to YR1,219 on February 26 before stabilizing at YR1,250 per US$1 over the course of March. Old rials circulating in Houthi-controlled areas remained stable during the month, trading at YR551 per US$1 on average.

The CBY-Aden resumed foreign currency auctions following a one-week suspension at the end of February due to a lack of funds. It held five FX auctions in March, with a total of US$150 million on offer. Only US$50 million was purchased. The March 2 auction was the second-least subscribed of the year, with only 14 percent of the US$30 million on offer sold. The last auction of the month, on March 28, was 37 percent subscribed. Since the beginning of the year, the CBY-Aden has held 13 FX auctions, with a total of US$430 million on offer, but only 36 percent has been purchased by Yemeni banks. The level of participation has been determined by an array of factors, including the fluctuating value of the rial and the foreign exchange stocks available to the CBY-Aden. Yemeni banks have reacted quickly to any announcement of new financial support and reduced their purchases at FX auctions to avoid losses arising from short-run misalignments of the real exchange rate. Importantly, the limited participation has coincided with an intensifying magnitude of the economic battle between the fragmented branches of the central bank in Aden and Sana’a over control of banking sector data, with the former attempting to regain unlimited access to banks’ data records, and the latter threatening increasingly restrictive measures to discourage compliance.

In mid-January, the Houthi-run CBY-Sana’a issued a decree banning banks and commercial traders headquartered in Sana’a from participating in the FX auctions or utilizing Letters of Credit under the CBY-Aden’s scheme, hampering demand for hard currency. Despite the ban, Yemeni banks and commercial traders headquartered in Sana’a continue to participate in the CBY-Aden’s auctions, according to a source based in Sana’a. This takes place on a limited scale, as officially banks are only allowed to participate in the financing of basic commodities imported, sold, and consumed in areas under the control of the government,

Houthis Increase Official Price of Cooking Gas

On March 8, Houthi authorities announced a 28 percent increase in the official price of cooking gas, from YR6,000 to YR7,700 (in old rials) for a 20-liter cylinder. During the war, the Houthi movement enacted a policy of selling cooking gas primarily through a neighborhood supervisor (aqil) and limiting its sale through official gas stations, giving the group a near monopoly over its provision. Many residents report having to pay bribes to Houthi-aligned aqils to receive gas. Repeated shortages at official stations have occurred in Sana’a and other areas under Houthi control, forcing thousands of households to rely on firewood for heating and cooking, or to purchase cooking gas on the black market at prices ranging between YR12,000-16,000 per cylinder. Profits from the black market are captured by Houthi-aligned traders.

Fuel From Saudi Grant Arrives in Hadramawt

On March 16, a shipment of oil derivatives arrived in Aden and was transported to Hadramawt to fuel power stations in the governorate. The fuel – 5,500 tons of diesel and 13,000 tons of mazut fuel derivatives – was the third shipment under a deal signed in September 2022 between the government and Saudi Arabia, under which the latter would provide US$422 million worth of fuel via the Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program to operate more than 70 power plants in government-controlled areas.

Houthis Pay Public Sector Employees Half-Month’s Salary

The Sana’a-based Ministry of Finance issued orders for the Houthi-controlled CBY-Sana’a to pay public servants a half month’s salary, covering the second half of July 2018. The payment, which is currently being disbursed, coincides with the holy month of Ramadan and is the first for civil servants working in Houthi-held areas since December 2022. In 2022, Houthi authorities made three full salary payments to public servants, who are owed nearly five years of back pay.

Cabinet Approves License for Oil Refinery in Hadramawt

On March 27, the government-affiliated Council of Ministers approved the license of a UAE-funded project to build oil infrastructure in Hadramawt governorate. The license includes the construction of an oil refinery, storage tanks, and a free industrial zone in the Al-Dhabba area of Al-Shihr district. The coastal area already includes an oil terminal, and the building of additional infrastructure would bolster the capacity of the state-owned Pertro-Masila oil company to extract, store, and refine oil and liquefied petroleum gas in the governorate. A government decree in 2002 approved a plan to establish refineries in Hadramawt with an initial production capacity of 50,000 barrels a day, and in 2004 the Hadramawt Refinery Company signed an agreement with the Korean companies Samsung Engineering and SK Engineering & Construction to build the refineries at a total cost of US$225 million, but the project was eventually abandoned.

The new project comes amid a halt on fuel exports by the government following Houthi drone attacks on oil export facilities in Hadramawt and Shabwa between October and November of the last year, including a strike on the port of Al-Dhabba.

Government Revises Fish Export Ban

The government’s Minister of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Fisheries, Salem al-Soqtari, issued a ministerial decree on March 27 amending a blanket ban on exporting seafood, carving out an exception for certain fresh fish and other marine life that have limited demand in local markets. Announced in February, the ban was rationalized as an attempt to increase the supply of seafood on the local market and to combat declining stocks.