Finland, Sweden and Norway all actively provide humanitarian aid to Yemen, despite limited public pressure to do so. Each of these Nordic countries also has engaged diplomatically, urging warring parties and other stakeholders to the negotiating table. Sweden acted as host for a set of talks that gave birth to the 2018 Stockholm Agreement, while Norway and Finland have made efforts to promote broad participation and inclusion in the peace talks. At the same time, however, all three have sold military equipment to Saudi-led coalition members. And despite public outcries condemning these arms shipments, temporary freezes on export permits have had a limited effect.

This article explores the roles Norway, Finland and Sweden have played in Yemen since 2014, to evaluate what can be expected from these countries in the near future. It also examines whether any recent events, such as the war in Ukraine and the public pressure to help Kyiv that followed, could lead to a rearrangement of foreign policy priorities in the Nordics at the expense of their humanitarian engagement in Yemen.

Provision of Aid

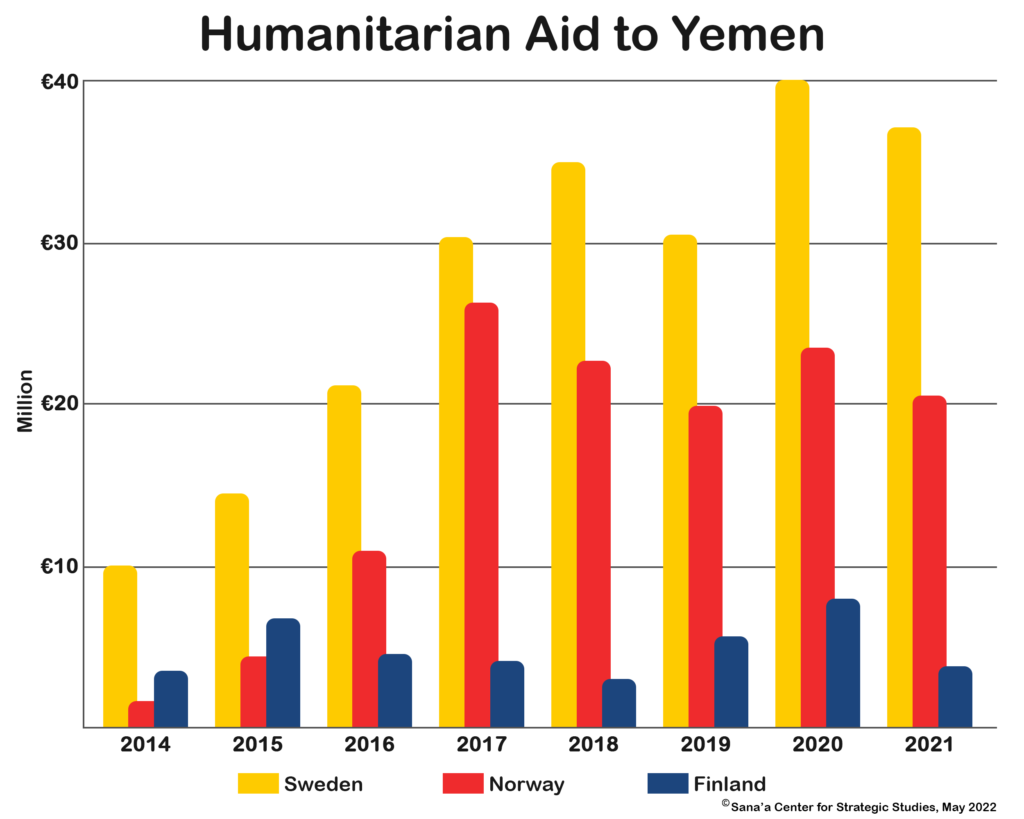

Sweden has provided the most humanitarian aid of the three Nordic countries, allocating about 240 million euros between 2014 and 2022, according to data provided by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida). In addition to this financial support, Sweden has used its political capital to co-host yearly conferences together with Switzerland and the United Nations to raise funds for humanitarian aid in Yemen since 2017.

To better understand why a seemingly remote country like Sweden would allocate taxpayer money to humanitarian work in Yemen, it is worth exploring the country’s long-term development policies and political identity. Firstly, most Swedish decision makers consider their country a humanitarian superpower. This identity springs partially from the notion that the country has lived in peace for 200 years, and that with this comes certain global responsibilities. Consequently, Sweden allocated 1 percent of its gross national income annually to humanitarian and development aid from 1968 to 1993, and again from 2005 onwards.

But the Swedish public has had something of a change of heart lately, particularly concerning the country’s migration and asylum policy. The most significant turn occurred in 2015, when 160,000 asylum-seekers mainly from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq arrived in Sweden, which left many wondering how well the country could successfully accommodate and integrate its new residents. Any talk of extending further foreign aid, whether to Yemen or Ukraine, a war that receives considerable media coverage in Sweden – could be more contested than in the past.

The resources needed to accommodate Ukrainian refugees also seem to have had ripple effects on foreign aid. In April 2022, Sweden’s government decided to cut Sida’s spending on development cooperation by 690 million euros. While the government has said that humanitarian aid will not be affected, development programs will face cutbacks.

According to Sofia Dohmen, adviser at the Conflict and Gender Unit for the Middle East and North Africa at Sida, the war in Ukraine will not affect Sweden’s humanitarian aid to Yemen. Instead, Sida will continue to allocate funds based on yearly assessments of Yemen’s humanitarian needs.

While Sweden considers itself a humanitarian superpower, Finland’s story is somewhat different. Having endured a civil war and a war for independence in the 20th century, Finland was on the receiving end of foreign aid at least until 1949. After this, the World Bank provided Finland with loans to rebuild the country. When Helsinki switched from being a recipient to also being a donor in 1956, it did so partially to distance itself from Eastern European countries and to align itself with Western Europe and its Nordic neighbors.

Between 2014 and 2022, Finland allocated roughly 43 million euros in humanitarian aid to Yemen, according to data provided by the Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This aid has often been allocated through international organizations such as the World Food Programme, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), Save the Children, the International Committee of the Red Cross or through domestic aid and development NGOs. Like Norway and Sweden, Finland has prioritized access to clean water, food and emergency aid to internally displaced persons in its humanitarian work in Yemen.

Since Russia’s attack on Ukraine, the Finnish government has come up with innovative ways to find money outside of the foreign aid budget to help Ukraine, including liquidating bitcoins, estimated to be worth around 73 million euros, confiscated by customs. This outside-of-the-box thinking may have been facilitated by the fact that UNICEF and the UNHCR have started to accept certain cryptocurrencies as forms of payment from foreign aid donors.

The public pressure to help Ukraine, raises the question of whether there is a risk of Helsinki rearranging its priorities and cutting the amount of humanitarian aid allocated to Yemen in favor of Ukraine in the near future. According to Eija Ranta, a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Helsinki, such a rearrangement seems unlikely.

“Finnish development and humanitarian NGOs have received significant donations from the public for their humanitarian work in Ukraine. This in turn will somewhat ease potential pressure on the government and other actors to rearrange their priorities,” Ranta said.

Norway’s peace-driven foreign policy has led to Oslo being an active mediator in conflicts, a steadfast donor of humanitarian aid and home of the Nobel Peace Prize. According to data provided by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, Norway allocated just under 133.55 million euros between 2014 and 2021 to humanitarian aid in Yemen and an approximately equal amount of funds in the form of foreign aid. Officials at the Norwegian Ministry for Foreign Affairs confirm that Oslo’s humanitarian aid for Yemen remains unaffected by the war in Ukraine.

Exporting Arms

Politics are seldom consistent. While each of these countries has donated funds for humanitarian work in Yemen, each has also authorized weapons sales to the Saudi-led coalition bombing Yemen. When such exports were made public, heated debates followed.

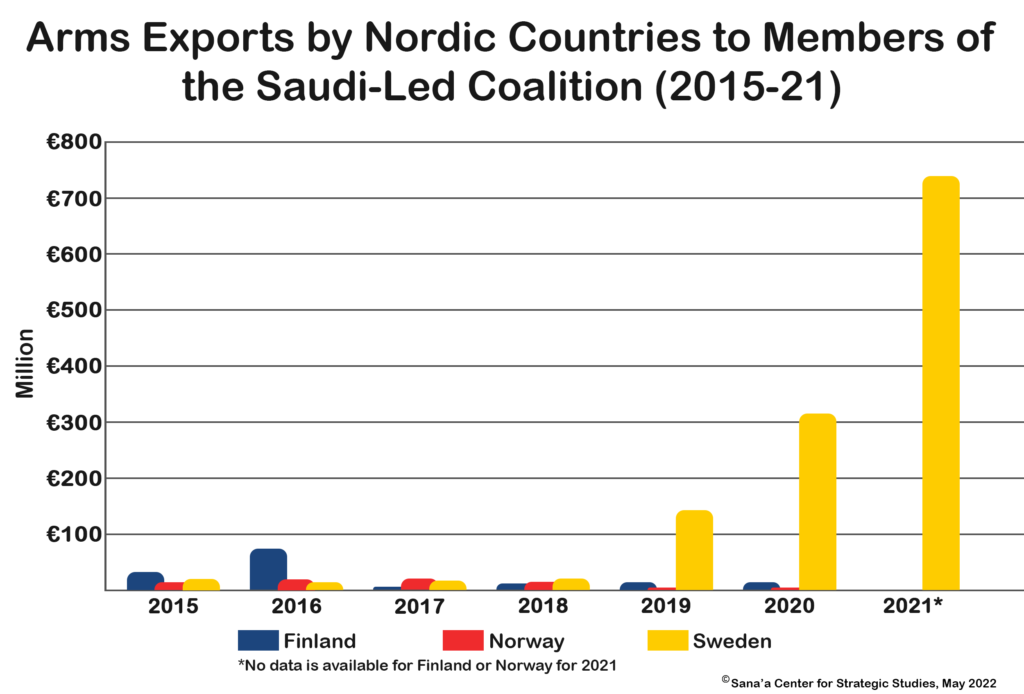

In Sweden, the first public outcry regarding arms trade with Saudi Arabia occurred in 2015. But the public debate on what became known as the “Saudi Affair” focused less on whether Swedish military equipment would end up in Yemen and more on the apparent contradiction of military cooperation with Saudi Arabia while pursuing a feminist foreign policy. As a result, cooperation between Riyadh and the Swedish Defence Research Agency (FOI) was not renewed. Despite this, the government has continued to face criticism due to arms exports to both Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. From 2015 to 2021, Sweden sold more than 132 million euros worth of arms to members of the Saudi-led coalition. In March 2021, it was reported that Swedish arms exports to countries within the Saudi-led coalition had doubled in 2020.

In Finland, a public debate over arms exports to the United Arab Emirates erupted in 2018 when Saferglobe, an independent peace and security think tank, revealed the scope to which Finnish arms manufacturers had made deals with both Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The criticism was further exacerbated when a Norwegian newspaper showed pictures of what appeared to be Finnish-made armored personnel carriers in Yemen. By the time the news broke, both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi had been major buyers of Finnish arms for five years; 2016 was particularly profitable for Finnish arms manufacturers, as UAE orders approached 68 million euros, accounting for 32 percent of all Finnish arms exports.

As a result of the public outcry, Helsinki halted all new permits for arms exports to countries involved in the war in Yemen. But the freeze only affected weapons and ammunition, and did not stop the export of multi-purpose defense materiel or maintenance and spare parts of already purchased products. In 2020, new permits were granted for exporting military vehicles to the UAE.

In Norway, public debates about arms trade erupted in 2018 and 2019, and on both occasions, they centred around exporting arms to Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The Norwegian arms trade is in theory regulated by a decision taken by the parliament in 1959, according to which Norway would not sell weapons to countries at war or at risk of war. However, Aftenposten, Norway’s largest newspaper, reported in 2021 that Norway sold 28 million euros of weapons and ammunition to the UAE between 2014 to 2018.

As a result of the public outcry, Oslo halted all permits for arms export to countries involved in the war in Yemen. However, as in Finland, these regulations only put a freeze on weapons and ammunition, which made it possible for Norway to continue to export multipurpose defense materiel.

Peace Efforts

The last area in which all three Nordic countries have engaged is promoting peace in Yemen through diplomacy and dialogue. In concrete terms, this has meant various efforts to gather the warring parties and other stakeholders for various negotiations and lobbying for peace-driven initiatives in the international community.

Since December 2018, Sweden and Norway have allocated approximately 100,000 euros per year to initiatives promoting peace in Yemen through the Yemen Peace Support Facility. This fund was put in place to support the Stockholm Agreement, a UN-backed deal that sought to avert a battle for the port city of Hudaydah. While the process itself was UN-led, Sweden took care of practical arrangements and logistics with the help of Oman and Kuwait.

While many hoped that the Stockholm process would have a greater impact on the ground, officials at the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs note that the meetings in Sweden and subsequent ceasefire and prisoner exchange were significant stepping stones. Sweden’s politicians, such as Foreign Minister Ann Linde, have underlined that promoting peace in Yemen is a high priority for the country. Linde met with multiple stakeholders in the conflict in 2020 and 2021 to promote peace through diplomatic means.

While Sweden has focused on getting the main warring parties together, Norway has put its efforts into track 2 negotiations that involve a more versatile set of parties on the ground. According to Julia Palik, a senior researcher at the Peace Research Institute in Oslo, these two tracks of peace negotiations are not mutually exclusive. Instead, they should, in an ideal scenario, feed into one another.

“Norway has also urged caution with regards to designating the Houthis as a terrorist group, in order to ensure that aid can be delivered to all areas in need. In fact, in February 2022 Norway abstained from a vote in the UN Security Council that designated the Houthis as a terrorist group,” Palik said.

According to Palik, Norway has made significant efforts to push for the investigation of sexual violence in Yemen’s war and to promote gender equality, which is also supported in Finnish and Swedish policy.

Finland’s diplomatic support of the peace process in Yemen has been somewhat more modest. According to information provided by Finland’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Helsinki focuses on supporting the peace process through its membership on the UN’s Human Rights Council, the EU’s peace work and its support for the UN Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen. Through its support for CMI – Martti Ahtisaari Peace Foundation, Finland, like Norway, has sought broader participation and inclusion in the peace talks.

Future Outlook

Finland, Sweden and Norway may be located far from Yemen, but all three have been engaged as donors of humanitarian aid, proponents of peace and arms suppliers to members of the Saudi-led coalition.

While the war in Ukraine continues in the Nordics’ backyard, it is unlikely to have a significant impact on their humanitarian engagement in Yemen — despite public pressure to help Kyiv.

As the Nordics are small or medium-sized countries, it’s normal and rational to prioritize continuity and stability in their foreign and humanitarian aid policies. This appears to be the case also for their engagement in Yemen. Yet, each country has demonstrated a willingness to act on short notice, as seen most recently in May when they contributed 5 million euros total toward a planned joint UN-Dutch operation to transfer of 1.14 million barrels of crude oil from the decrepit FSO Safer oil storage facility moored off the Hudaydah coast in an effort to prevent a potential environmental disaster in the Red Sea. Despite their humanitarian work and efforts to promote peace, it is also likely that each Nordic country will continue to sell materiel to conflict zones around the globe, including the Arabian Peninsula.

This article is part of a series of publications by the Sana’a Center examining the roles of state and non-state foreign actors in Yemen.

Editor’s note: The governments of Norway and Sweden are donors to the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. Crisis Management Initiative (CMI) – Martti Ahtisaari Peace Foundation is a Sana’a Center partner.