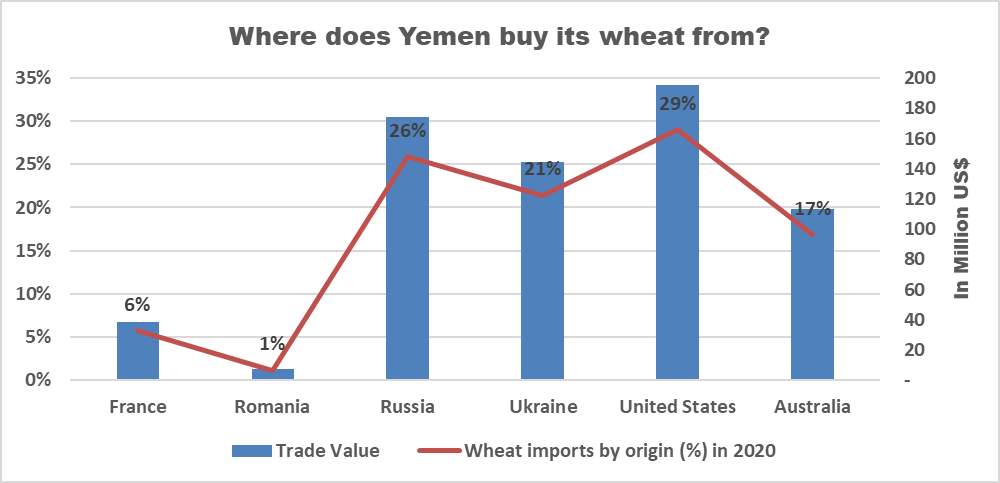

Yemen faces an imminent food crisis stemming from the Russian invasion of Ukraine, according to the UN, international organizations, Yemen’s largest wheat importer and others. Yemen, which imports up to 90 percent of its basic food needs, is highly vulnerable to exchange rate volatility, price shocks in international markets and disruptions in global food supply chains. Russia and Ukraine together account for nearly a third of the world’s wheat supply and in 2021 supplied 42 percent of Yemen’s wheat (20 percent from Ukraine, 22 percent from Russia). Meanwhile, the World Bank forecasts that global wheat prices will jump more than 40 percent in 2022, to an all-time high (in nominal terms) due to sanctions against Russia, the Russian blockade on Ukraine’s Black Sea ports and other factors.

Sourcing wheat from other countries will likely be complicated and expensive for Yemen, as it will for numerous other developing countries. This is due to both the general shortage of wheat on the global market and the fact that Russian and Ukrainian wheat has historically been cheaper than other varieties, given that it is of lower quality and protein content than competing varieties on the global market.

On May 16, the Hayel Saeed Anam (HSA) Group, Yemen’s largest wheat supplier, warned that supply chain disruptions and price spikes stemming from the Russian invasion of Ukraine could spur “potentially catastrophic famine” in Yemen. In March, the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification’s Famine Review Committee had reported the Russia-Ukraine war may require it to reassess whether an official famine classification could become warranted in various parts of Yemen. In a press statement, HSA noted other factors playing into Yemen’s food security crisis: the country’s strategic stocks of wheat are running low; the private sector’s diminishing purchasing power is eroding its ability to resupply the local market with essential foodstuffs; and India’s May 13 decision to suspend wheat exports in an apparent bid to curb domestic price surges.

Yemeni Trade Minister Mohammed al-Ashwal told Reuters that the government and importers were looking for alternate markets to compensate for lost wheat imports from Ukraine and Russia. Yemen was among several countries, including South Korea, Oman and the UAE, which sent requests to the Indian government for exemptions to the export ban. On May 27, Yemeni Foreign Minister Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak thanked India, via Twitter, for granting Yemen the exemption. The quantity of wheat India agreed to supply, and whether it is sufficient to address Yemen’s food needs, remains unclear. Several media outlets reported that India’s wheat harvest is likely to fall substantially this year due to a sudden rise in temperatures and heavy droughts.

Yemen’s weak agricultural production capacity and heavily concentrated import market increase the country’s vulnerability to food insecurity. Significantly increasing local food production is unrealistic at present given the country’s weak agricultural infrastructure, water scarcity and the high cost of fuel, which has driven up farming costs. The wheat import market is dominated by only a few companies. In 2016, the World Bank reported that ten companies controlled nearly 99 percent of all wheat imports into Yemen. Of these, two companies controlled about 70 percent of total wheat imports: HSA Group at 52 percent and Fahem Group at around 26 percent. The conflict has likely exacerbated the concentration, with HSA Group currently controlling at least 60 percent of the wheat import market in Yemen, according to Sana’a Center Economic Unit estimates.

The Russia-Ukraine war comes as Yemen is already experiencing one of the world’s largest humanitarian crises and a dramatic fall in funding for the relief response. More than 17 million Yemenis are food insecure, including 5.6 million experiencing emergency levels of food insecurity and 31,000 classified as in catastrophic conditions. The UN has been able to raise only a quarter of its US$4.3 billion international humanitarian appeal for Yemen this year. Citing a significant funding shortfall, the World Food Programme reduced food rations for 8 million people in January, and has warned it may make further cuts.

In its statement, HSA Group warned that without urgent action, hundreds of thousands of Yemenis could face extreme hunger in a matter of months. It called for immediate international intervention and offered potential solutions to ensure sufficient wheat supplies reached Yemen. These included: strengthening Yemeni wheat importers’ priority access to global wheat supplies; establishing an internationally supported “special import finance fund” to give Yemeni traders rapid access to import financing; and a mechanism by which international organizations or financial institutions could provide guarantees to allow Yemeni food importers to extend payment terms with their international suppliers to 60 days. It is important to note that HSA group, as Yemen’s largest wheat importer, would stand to gain most from any assistance to private sector wheat importers. A previous import financing mechanism led to accusations of embezzlement and collusion against the conglomerate, other importers and the Yemeni government. In response to the HSA group request, Prime Minister Maeen Abdul-Malik met virtually on May 19 with the UN’s head of humanitarian affairs and emergency relief, Martin Griffiths, and called for the establishment of a special emergency fund to finance imports to Yemen and provide preferential terms for Yemeni wheat importers. However, as of this writing, this has not materialized.

Funding Call to Address Threat of Red Sea Oil Tanker Disaster Falls Short

On May 11, a pledging conference in The Hague, co-hosted by the UN and the government of the Netherlands, failed to raise the funds the UN says are necessary to address the catastrophic environmental threat posed by the FSO Safer oil terminal. The FSO Safer is a decrepit, 45-year-old single-hulled oil tanker moored off the coast of Hudaydah with more than one million barrels of oil aboard – four times the amount spilled in the infamous 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster. The vessel has received almost no maintenance in more than seven years and has been described as a “floating bomb” due to the explosive gasses that have built up in the holding tanks.

The conference followed a UN announcement in February that an agreement had been reached with Houthi authorities to address the situation. The first stage of the plan was to be a four-month emergency operation to transfer the oil to a temporary vessel, with a permanent replacement to be moored at the site within 18 months. The UN estimates the first stage – including the salvage operation, leasing the new vessel, crew and maintenance – will cost some US$80 million, while total cost will amount to US$144 million.

The UN had said it intended to begin the first stage of the plan in the second half of May. However, funds pledged at the conference amounted to just US$33 million. Of this, the Netherlands pledged almost US$8 million, with the remainder coming from Germany, the UK, the European Union, Qatar, Sweden, Norway, Finland, France, Switzerland and Luxembourg. Including previously committed funds, there was US$40 million available for the plan following the conference, according to UN Resident Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen David Gressly. No further pledges had been made as of this writing.

Among the glaring omissions from the UN plan is any proposal for the sale of the more than million barrels of oil, and how the proceeds of such a sale would be distributed. This has been a source of contention between the warring parties that blocked progress on the issue. In 2019, the oil was valued at roughly US$80 million. While it has likely degraded somewhat since then, it should retain a significant portion of its value, especially in light of the recent spike in global oil prices.

YR Relatively Stable Against Foreign Currencies

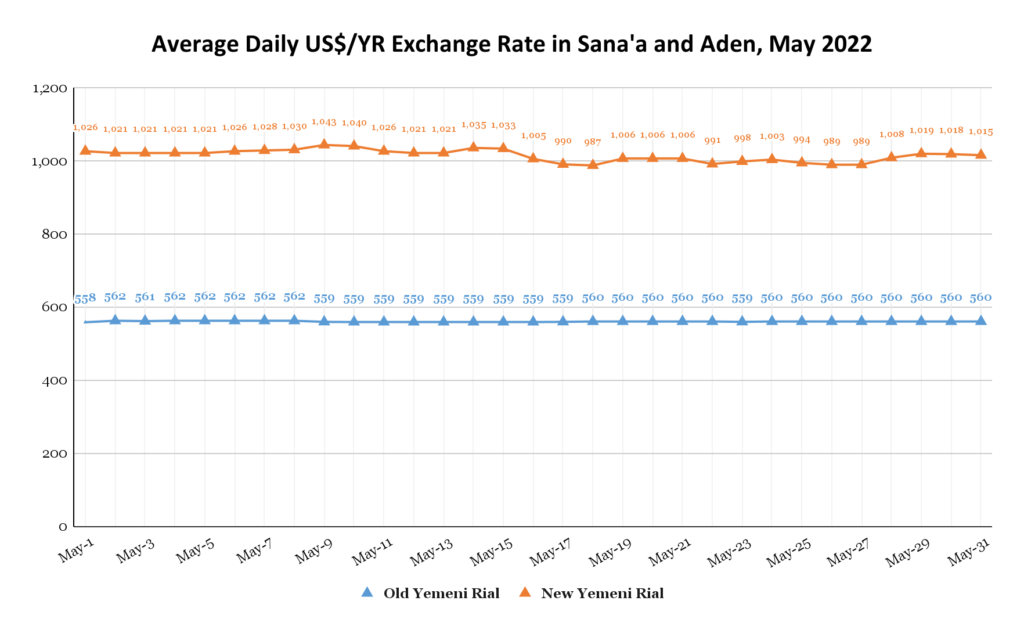

The exchange rate of the Yemeni rial experienced relatively slight fluctuations in government-held areas during May, gradually appreciating from YR1,026 per US$1 at the beginning of the month to YR987 on May 17, a gain of approximately 4 percent, before retreating slightly and ending the month to YR1018 per US$1. This follows more than a year of steady depreciation and then wild volatility in April when, following the announcement of US$2 billion in Saudi and Emirati support for the Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden), the currency increased as much as 40 percent in value before rapidly shedding these gains. In Houthi-controlled areas, the exchange rate remained relatively stable in April, trading in a narrow band around YR560 per US$1.

Riyadh Releases Final Deposit Installment, CBY-Aden Ups Foreign Currency Auctions

On May 16, Riyadh agreed to extend the US$2 billion deposit it gave the CBY-Aden in 2018 and to release its final installement, worth US$174 million. The following week, on May 24, the CBY-Aden held its 21st foreign currency auction of 2022, with a total of US$30 million on offer. It was the first time since November 2021, when the bank began using the Refinitiv platform for currency sales, that the amount on offer at an auction had surpassed US$20 million. The move appeared to be in line with the CBY-Aden’s recent shift toward adopting a contractionary monetary policy, which draws on its available balance of foreign currency reserves to purchase Yemeni rials from the market to reduce the quantity in circulation and help stabilize the exchange rate.

To attract banks to bid, the CBY-Aden offered a preferential exchange rate of YR937 per US$1, an almost 7 percent premium over the prevailing market exchange rate. However, only 72 percent of the foreign currency on offer was sold. Banks’ reluctance to fully subscribe to the auction likely indicates that they see new Yemeni rials, printed by the CBY-Aden since 2017, as being undervalued, and are anticipating further appreciation in the YR/US$ exchange rate. This is likely to result from Saudi and Emirati financial support to CBY-Aden, worth US$2 billion, announced in April but as yet undeployed. A positive international response to Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek’s May 19 call for a special emergency fund to offer financing to Yemeni wheat importers would also likely have a positive impact on the exchange rate.

Other Economic Developments in Brief:

- May 20: During a meeting with Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati, Yemen’s ambassador to Lebanon, Abdullah al-Deais, renewed the call for the release of Yemeni bank funds being held by Lebanese banks. It is estimated that Yemeni commercial banks had some US$240 million deposited in correspondent accounts at Lebanese banks in 2019, shortly before the latter froze most foreign currency withdrawals due to a liquidity crisis, which remains ongoing.

- May 22: The Yemeni government’s Minister of Electricity and Energy signed an agreement with Siemens Middle East Limited to replace and maintain three gas turbines at the Marib Gas Power Plant (MGPP), with the associated cost of US$40 million covered by the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development. The MGPP is a 342-megawatt (MW) natural gas power station in Marib governorate which, prior to the ongoing conflict, provided roughly 40 percent of Yemen’s energy needs. Currently, it is producing only 40 MW, roughly 12 percent of its capacity.

- May 24: The UN Special Envoy to Yemen concluded two days of talks with a broad range of Yemeni economic experts in Amman, Jordan. The aim of the talks was to identify economic priorities and opportunities to be pursued in a multi-track peace process. Among the topics discussed were coordinating financial and monetary policies between the warring parties, exchange rate stabilization, public revenues, civil servant salaries, inflation and barriers to commerce and movement.

- May 26: The head of the Yemeni government’s Presidential Leadership Council (PLC), Rashad al-Alimi, directed the CBY-Aden to assess the success of a previous mandate, issued on August 5, 2021, that commercial and Islamic banks move their headquarters from Sana’a to Aden, and what further could be done in this regard. Regulation of the country’s banks has been a contentious issue and a major facet of the economic war between the belligerent parties. The rival branches of the fragmented CBY started to escalate competition for control over access to data held by Yemeni banks and money exchange outlets toward the end of 2020. This intensified during August of last year when the CBY-Aden ordered Yemeni commercial and Islamic banks to relocate their headquarters to fully operate from Aden and imposed punitive measures on non-compliant banks, including large fines and court referrals. Al-Alimi’s recent directive could foreshadow further escalation on this front.

- May 25: The Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) increased the official price of gasoline by 6.6 percent in Houthi-controlled areas, from YR600 to YR640 per liter. In April, the YPC raised the price of gasoline from YR495 to YR630, roughly 27 percent, before lowering it slightly to YR600 on April 24. Notably, both these increases came after the beginning of the Ramadan truce in early April, which saw fuel imports restarted through the port of Hudaydah and ended apparent gasoline shortages in Houthi-held areas.