Executive Summary

Executive Summary

Shabwa governorate, perched centrally at the foot of Yemen’s mountainous highlands and stretching to the Gulf of Aden, is at a crossroads of Yemeni identity as well as geography. As part of the former Marxist South Yemen that unified with the northern Yemen Arab Republic in 1990 and then attempted to break away four years later, Shabwa shares the southern sense of marginalization and alienation that has bred popular support for secessionist elements in recent years. In the 16 years that followed the 1994 civil war, many of Shabwa’s tribal and political elites were co-opted by former President Ali Abdullah Saleh into toeing the regime’s line. But those relationships did not prove strong enough to deliver the governorate into Saleh’s hands after he allied with the armed Houthi movement, Ansar Allah, to seize Sana’a in late 2014 and expand southward.

The Houthi-Saleh alliance briefly controlled large swathes of Shabwa, including its capital Ataq, in the early months of the war. By the end of the summer in 2015, Houthi-Saleh forces were confined to Wadi Bayhan in the governorate’s northwest corner, where they held their ground for two more years until their alliance of convenience unraveled in December 2017 infighting, ending with the killing of Saleh. Another non-state actor, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), had expanded in much of rural Shabwa prior to the arrival of Houthi-Saleh forces and managed to hold on longer than the alliance. While the Saudi-backed army of the internationally recognized government of President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi was credited with driving Houthi-Saleh forces out of Shabwa, UAE-backed tribal militias known collectively as the Shabwani Elite forces were responsible for routing AQAP and its local affiliate, Ansar Al-Sharia, from the governorate.

These were major victories for the coalition-backed Yemeni forces that allowed local authorities to turn their attention to governance. However, conflicting political agendas bubbled to the surface and by the summer of 2019, several brigades from the Shabwani Elite forces were working hand-in-hand with the UAE-supported secessionist group, the Southern Transitional Council (STC), to eject Hadi-appointed officials and troops from the governorate.

Shabwa has experienced some security improvements during the current war, which have aided development efforts despite the shifting backdrop of armed political struggle. The governorate’s oil reserves and network of pipelines extending to export facilities on the Arabian Sea have allowed Shabwa’s local authority to kick-start its economy. Having negotiated a 20 percent share of those oil sale revenues with the central government, local officials have been able to manage the governorate’s affairs with a degree of autonomy for the first time in modern history. Like the oil-producing Marib governorate to the north, Shabwa has used its newfound political autonomy and budget to launch development projects that long seemed out of reach.

This paper provides an overview of the political and tribal dynamics that resulted in Shabwa’s marginalization in recent decades. It then examines the most recent power struggles for control of the governorate and its resources since the outbreak of war in 2015 and details how it has become relatively secure compared to many parts of Yemen.

Introduction

Shabwa is the third-largest governorate by area in Yemen. Located in the center of the country, Shabwa is flanked by four governorates: Hadramawt to the east, Marib to the north, and Abyan and Al-Bayda to the west. Its geography consists of rugged mountains, plateaus and valleys in the northwestern and central parts of the governorate flanked by the Ramlat al-Sabatayn desert in the northeast and coastal desert along the Arabian Sea. Shabwa’s southern coast, consisting of about 300 kilometers of beaches, is dotted with fishing villages, the most important of which are Bir Ali, Hawra and Balhaf. The port of Balhaf at the eastern end of Shabwa’s coast is the site of the biggest foreign investment on Yemeni soil, the Balhaf liquified natural gas (LNG) export terminal.

Composed of 17 districts spanning about 43,000 square kilometers, the governorate has one of the lowest population densities in Yemen. Shabwa’s estimated population of between 600,000 and 700,000 is dispersed across several small urban centers – the largest of which are the capital Ataq, Al-Alya and Azzan – as well as numerous villages and hamlets.[1]

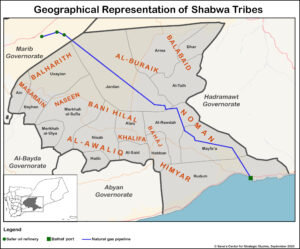

The vast majority of Shabwa’s population falls within nine main tribes and several southern Hashemite families, almost all of whom are Shafei Sunni.[2] The largest tribe is the Al-Awaliq, mainly located in Al-Said, Nisab and Hatib districts, with a presence in Ataq and Merkhah al-Sufla districts. The Bani Hilal tribe is concentrated in Ataq, Merkhah al-Sufla and Jardan districts. The Masabain tribe is predominantly in Bayhan, Ain and Usaylan districts. The Noman tribe is in Mayfa’a and Al-Rawdah districts. The Balabaid tribe is in Arma, Al-Talh and Duhur districts. The Himyar tribe is in Habban and Rudum districts. The Al-Buraik is in Arma and Jardan districts. The Balharith tribe is in Usaylan district.

In addition to tribes, Shabwa has a presence of Hashemites, or descendents of the Prophet Mohammed. Prominent Hashemite family names in the governorate include Jeffri, Mihdhar, Hamid, Jailani, Shareef and Junaidi. Another group, the Bahaj, are what is known as mushayekh, or religious clerics, and are in Habban district.

Historical and Cultural Background

Shabwa has a rich cultural history that stretches back to antiquity. The ancient city of Shabwa, located in the governorate’s northwestern Arma district, was the capital of the Hadramawt trading kingdom from the 4th century BC to the 3rd century AD and an important stopover along the Frankincense Trail that linked the Mediterranean world and the Arabian Peninsula.[3] Other important heritage sites include the historical city of Mayfa’a and the Roman port of Qana near the coastal town of Bir Ali.

Within the current borders of Shabwa are the capitals of three ancient Yemeni trading kingdoms (Hadramawt, O’san and Qataban). Shabwa is thus home to many archaeological and cultural heritage sites. It also included many Yemeni Jewish communities before they were resettled in Israel as part of operation “Magic Carpet” from 1949-1950.[4]

In modern times, Shabwa formed the outer edges of the British protectorate. When British rule ended in 1967, Shabwa was forcibly integrated into the former People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY),[5] with the central government based in the southern port city of Aden. The PDRY unified with the Sana’a-based Yemen Arab Republic to form the Republic of Yemen in 1990. The unification project nearly unraveled in a brief but bloody civil war in 1994, when the northern army, backed by loyalist southerners, crushed an attempt by some southern elements to once again make South Yemen an independent state. That war, like the current struggle between the Hadi government and the STC that was founded in 2017 by disaffected southern leaders, has roots in a long history of political tension between two rival groups in the south: the Zumra, which includes Hadi and his allies, hailing from Shabwa and Abyan governorates, and the Toghma of Al-Dhalea and Lahj governorates, from which most of the STC leadership hails.[6] The most violent example of this struggle was the bloody 1986 South Yemen Civil War, fought among leaders of the Yemen Socialist Party. After a few weeks of fighting in which more than 10,000 people were killed, the Toghma emerged victorious. Hadi and thousands of others from Abyan and Shabwa fled to the north, only to mete out revenge eight years later when the Saleh regime crushed the Toghma-led bid for secession.

Control over the governorate’s oil resources has been contentious since commercial quantities were discovered by the Soviet Union in the mid-1980s. In the current conflict, the Hadi government has maintained control of the oil fields in northern parts of Shabwa in the face of advances by forces loyal to the STC, which seeks to return the governorate and its resources to southern stewardship.[7]

Despite producing oil since the early 1990s, Shabwa has benefited little from the lucrative industry.[8] The Sana’a-based government of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh channeled much of the nation’s oil wealth into patronage networks, and the development of most areas in Yemen outside the capital, including Shabwa, was not a priority.[9] Some of the limited benefits that Shabwanis have enjoyed from the oil and gas industry have come from foreign oil companies that offer donations and sponsor development projects and local employment to facilitate their operations.[10]

Tribes, criminal gangs and Al-Qaeda operatives in Shabwa have recognized the importance of the oil industry to the national economy and targeted oil pipelines and other industry infrastructure as a means of leverage in negotiations with the central government.

Since the beginning of Yemen’s current conflict in late 2014, Shabwa has been a destination for tens of thousands of internally displaced people (IDPs) fleeing conflict zones in Yemeni governorates to the west in search of a safe place to live and work. Unlike many other urban hubs in southern governorates, Shabwani cities have been more welcoming to IDPs from northern governorates.[11] The influx of displaced people has, however, strained public services and housing across the governorate.

In the Geographic and Economic Center of Everything

Shabwa’s Oil and Gas Economy

Shabwa is one of Yemen’s main oil-producing governorates alongside Hadramawt to its east and Marib to the northwest. The first commercially viable discovery of oil in Shabwa was announced in 1987 while the governorate was still part of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen).[12] But it was not until after Yemeni unification that major oil deposits were identified in Shabwa: Wadi Jannah’s Block 5 in northwestern Usaylan district was discovered in 1996, Block S1 in Usaylan was identified in 2003 and Al-Oqlah’s Block S2 in the northeastern district of Arma was found in 2005.

About a decade after the 1984 discovery of major gas reserves in neighboring Marib governorate’s Block 18, plans were put in place to transfer the gas through a pipeline to Shabwa’s southern port of Balhaf.[13] Initially built to export Shabwani oil from the small deposits discovered in the northern Jardan district’s Block 4 in 1987, the Balhaf port was developed into the biggest foreign industrial investment in Yemen by a consortium of Yemeni and international companies.[14] The first shipment of liquified natural gas (LNG) left the port in November 2009.[15]

All oil and gas production in Shabwa ceased shortly after the outbreak of war in 2015, and since then only limited operations have resumed in the governorate. According to the Shabwa branch of the Ministry of Oil and Gas, current production in the governorate is between 8,000 and 9,000 barrels per day, compared to 69,000 bpd before the war. Block S2 in Al-Oqlah district, operated by the Austrian oil and gas company OMV, is the only facility that has come back online during the war.[16] It resumed operations in April 2018.[17] Shabwa has also started exporting oil from Marib’s Block 18, which prior to the conflict was pumped west to the Ras Issa port near the Red Sea city of Hudaydah.[18]

Shabwa During Saleh Era, Hadi Transition and Now

A Shuffle Like No Other: GPC, Islah and the STC

Shabwa has benefited little from its hydrocarbon riches, and Saleh’s political marginalization of southern Yemen after the 1994 civil war only made matters worse. As a result, negative sentiment toward the national government is common in the governorate. Groups in Shabwa opposing the central government range from the peaceful southern separation movement known as the Southern Movement[19] to Islamist militants who take advantage of the governorate’s remote areas to operate more freely.

When Yemen’s 2011 Arab Spring-inspired protests started in Taiz city and later took off in the capital Sana’a, Shabwanis also took part. From a protest camp established in the capital, Ataq city, locals demanded Saleh’s resignation, the end of corruption in the governorate and a rightful share of oil and gas revenues produced from Shabwa’s fields. At the time, all of these revenues were sent directly to the central government, which controlled disbursement for local budgets. The governorate was able to avoid bloody confrontations after then-Governor Ali Hassan Al-Ahmadi struck a deal with protest leaders to not take part in the power struggle in Sana’a and to follow whomever ended up in charge.[20]

Several notable Shabwanis were close to Saleh during his 33-year rule, including the former secretary-general of the president’s General People’s Congress (GPC) party, Aref Awadh Al-Zukah, who was killed alongside Saleh by the armed Houthi movement in December 2017. The last prime minister to serve under Saleh, Mohammed Mujawar, who was badly injured alongside the president in the assassination attempt at Al-Nahdain Mosque in 2011, also hails from Shabwa.[21]

Saleh had appointed eight GPC-affiliated governors of Shabwa since the 1990 unification, starting with Dirham Abdoh Noman, who held the office from 1991 until 1994, when the civil war broke out.[22] He was succeeded by Ahmed Ali Mohsen Lahwal, the first Shabwani governor of Shabwa. As the head of security in Shabwa before the war, Lahwal fought against secession of the governorate. Saleh rewarded Lahwal’s effort by appointing him governor when the war ended. In 1995, Lahwal was sent to govern Al-Mahwit governorate. In his place, Saleh appointed Ali Sheikh Omar, who fought against the separatists in 1994 as part of the Zumra group. An Abyan native, Omar understood Shabwani society and tribal politics and was a member of the GPC.[23] These attributes made him a trusted figure to lead Shabwa during the turbulent period following the brief civil war. Mohammed Saleh Qaraa succeeded Omar from 1997 to 1999.

Ali Ahmed al-Rassas, a tribal leader from Al-Bayda governorate, led Shabwa from 1999 to 2005. Mohammed al-Magdashi and Mohammed Ali al-Ruwaishan each served two-year terms as governor before Al-Ahmadi, the last Shabwa governor appointed by Saleh, took office in 2009. After finishing his term in 2012, Al-Ahmadi was appointed by Hadi to lead the National Security Bureau intelligence agency in Sana’a. Of the eight Shabwa governors Saleh appointed, only Al-Ahmadi and two others (Lahwal and Qaraa) were natives of the governorate. By contrast, all five governors appointed by Hadi since 2012 are Shabwani, an apparent effort to mollify some of the deep-seated grievances in the governorate that had become entrenched during the Saleh era.

In 2012, Hadi appointed Shabwa’s first non-GPC governor, Ahmed Ali Bahaj, who belonged to Yemen’s Islah party. His time in office spanned the political transitional period and stretched into the early months of the Houthi-Saleh coup. Bahaj stopped oil and gas production in Shabwa in January 2015 after the Houthis abducted Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak, an aide to Hadi, in Sana’a.[24] Bin Mubarak was released 10 days later. Bahaj was one of the first governors to reject Houthi rule after the group dissolved parliament and formed a new transitional authority in February 2015.[25] He died in northern Shabwa in a May 2015 car crash. He was succeeded by Abdullah Ali Furaysh, previously the governor of Amran and Marib, who was in his 70s and served only briefly as Shabwa’s governor before dying in Jeddah in October 2016. In his place, Hadi appointed GPC-affiliated Ahmed Hamed Lamlas, who in the spring of 2017 joined the newly formed pro-secession STC, which was considered illegal at the time, while he was serving as governor. Hadi dismissed him as governor in June 2017. The STC has since emerged as the main political challenge to Hadi’s government in southern governorates.[26] Lamlas was succeeded by Major General Ali bin Rashid al-Harithi, who was formerly the director of Shabwa’s Mayfa’a district. He is currently a member of the upper house of parliament, the Shura Council.

The current governor of Shabwa, Mohammed Saleh bin Adio of the Islah party, was appointed in November 2018. He was virtually unknown in Yemen’s political scene before his current assignment, though he had served as first deputy under Al-Harithi. Bin Adio is a sheikh from the Adio branch of the Laqmosh subtribe, which is part of the larger Himyar tribe. He and the prominent Shabwani Elite commander of the Azzan axis, Mohammed al-Bohar, are from the same tribe and village, Al-Khabir, in Habban district, which bin Adio represented in Shabwa’s local council from 2006 to 2011. Bin Adio’s time in office has been relatively quiet compared to his predecessors, who oversaw the retreat of Houthi forces from the governorate in late 2017 and Shabwani Elite forces’ push against AQAP, which significantly weakened the group’s presence in Shabwa in late 2018. In light of those developments, Bin Adio has been able to focus more on governance.

Decentralization Brings Oil and Gas Revenues, Development

Around the time Bin Adio was appointed governor in late 2018, Shabwa started receiving about 20 percent of the oil revenues generated from its only functioning facility, Al-Oqlah’s Block S2.[27] In January 2020, Bin Adio said Shabwa had received $31 million in oil sales from 13 shipments of crude produced at Al-Oqlah since mid-2018.[28] The Ataq-based local authority has used the funds to launch various infrastructure projects including rebuilding a bridge destroyed in the war, restoring Ataq’s airport and launching electricity projects.[29] The flurry of development, an unusual sight in a governorate far more familiar with struggling to finance projects,[30] boosted Adio’s popularity.

In January 2019, as part of an anti-corruption agenda, bin Adio issued an arrest warrant for Saleh Ali Bafayadh, the director of the local branch of the government-owned Yemen Oil Company. Bafayadh was accused of embezzlement of public funds and fraud, but critics at the time speculated that the allegations were politically motivated.[31] When government officials tried to pressure Bin Adio to back down, the governor threatened to resign.[32] Ultimately, Bafayadh was forced to step down from his position in the oil company, and no further action has been taken, a relative of Bafayadh confirmed.[33]

Around the same time, officials in Ataq city launched a campaign to regain control of government buildings from armed criminal groups who had seized them in the chaos of 2015. By early 2020, all of the buildings in the capital had been returned to the government.[34] A second phase of the campaign is planned to reclaim other offices and properties in districts outside the capital.

Shabwani residents have attributed the restoration of some services to the current local authority, but much remains to be done in the health and education sectors and in the provision of electricity and water, according to interviews with four local civil society and government leaders. Aden University has two branches in Ataq, a college of oil and minerals and a college of education, but many Shabwanis travel to neighboring Hadramawt or south to Aden to attend university. They also complain the central government has neglected Shabwa’s economic potential by not further developing and utilizing the Qana seaport in Bir Ali and the airport in Ataq, which currently functions only as a base housing Saudi forces. Other concerns include the sporadic payment of government salaries and demands for transparency in the handling of government spending in general.[35]

Bin Adio’s power as governor also has been increasingly challenged by STC aspirations in the governorate. Confrontations between the STC and government forces reached a climax in August 2019, following the separatist group’s seizure of the interim capital, Aden, with the help of the UAE-backed Security Belt forces. Working through the Shabwani Elite forces formed by the UAE to help secure the governorate and fight AQAP, and through the newly formed southern resistance forces, the STC tried to overrun Ataq in June and August.[36] By the end of August, however, government forces had regained control of virtually all areas of Shabwa except Balhaf port and Al-Alam military camp, where UAE forces continue to operate. Even in the absence of the STC, Bin Adio’s authority has faced continued challenges. He survived an assassination attempt by unknown assailants using an improvised explosive device in June 2020 and has repeatedly complained of UAE interference in the governorate.[37] Despite his relative popularity as governor, Bin Adio is set to be replaced in line with the terms of the Riyadh Agreement, the unrealized power sharing deal signed in November 2019 to ease the government-STC infighting in southern Yemen.

Security: The Shabwa Elite, Disarming Civilians and Returning Security

A number of efforts have been made to reform Shabwa’s security sector in recent years, starting with the recruitment of locals instead of relying on northern forces deployed by central authorities to the governorate. The previous situation had fueled grievances of southern activists and some tribesmen, who viewed the northern security forces as outsiders. The Shabwani Elite forces, formed and trained by the UAE for counterterrorism operations and local security, were recruited from the tribes in each district in which they were to be deployed.[38]

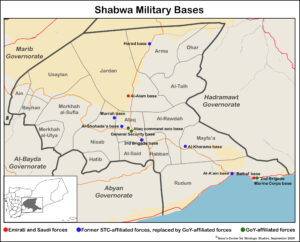

The First Brigade, trained at Al-Khalidia Camp in Rumah district of Hadramawt, deployed in August 2017 in Shabwa’s Balhaf port and its surroundings. Its members were mainly from the coastal tribes of Al-Lakhnaf, Al-Adhmi and Al-Sulaiman. Its most recent commander, Khalid Al-Adhmi, took over after Jalal bin Aggag was killed in an AQAP attack in January 2019 in Shabwa’s northwestern Merkhah al-Sufla district.[39] The Second Brigade in Azzan was led by Mohammed Al-Bohar and mainly consisted of Himyar and Noman tribesmen. The Third Brigade in Al-Said district was headed by Salem Hantoosh and recruited mainly Al-Awaliq tribesmen, most of whom chose not to take part in the August 2019 clashes between the Shabwani Elite and the government forces. The Fourth Brigade, entrusted with securing Ataq, was drawn from various Shabwani tribes under the leadership of Wagdi Baoum. The Fifth Brigade, headed by Mohammed al-Qahili, was based at Al-Alam camp in Jardan district, with its members consisting mainly of Bani Hilal tribesmen. Al-Alam, which continues to host Emirati and some Saudi forces, as well as a small number of Shabwani Elite forces, has been a source of recurring tensions in the governorate as Gulf forces travel back and forth between Balhaf and the camp without fully coordinating with the government.[40] The Sixth Brigade, located in Arma district and headed by Mohammed Al-Kurbi until he died of a heart attack on July 20, 2020, was primarily made up of Balabiad and Al-Buraik tribesmen. Like the Third Brigade, the Sixth Brigade did not join the August 2019 Shabwani Elite-army clashes. The Seventh Brigade, which was based in Merkhah al-Sufla district, was led by Majed Lamroq and made up of fighters mostly from the Nasieen branch of the Bani Hilal tribe.

Trained for counterterrorism operations, the Shabwani Elite were never meant to take on expanded wartime roles like those of the army, and they were not equipped to do so.[41] Some former Elite members interviewed attributed these factors to the Shabwani Elite’s fairly quick retreat in the face of Yemeni army forces in August 2019. There also had been clashes within the 8,000-strong forces, rooted in existing tribal conflict and clan affiliations, which prevented them from forming a unified front against government forces.[42] Regardless of the reasons, all Shabwani Elite brigades have since been disbanded and their posts taken over by government forces, in line with the Riyadh Agreement’s requirement that all security and military forces in southern governorates be reorganized under the command structures of the Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Interior.[43] They continue, however, receiving their salaries of SR1,500 a month, which provides a welcome injection of foreign currency into the local economy.

Another security-related reform has been gun control. In Shabwa, like many rural areas beyond the reach of Yemen’s central government, carrying firearms was commonplace during the Saleh era. In late 2017, the Shabwani Elite forces took the unprecedented step of prohibiting the public from carrying weapons in urban centers including Ataq, Azzan and Habban. Even though the Elite forces have since been replaced by government forces throughout the governorate, the weapons ban is still largely in place.[44]

The Houthis: From the Mountains They Descended

Shabwa’s political and military landscape started to change rapidly in early 2015, as the Houthis pushed toward Yemen’s southern port city of Aden from Sana’a. In preparation for a Houthi invasion, Shabwani tribes trained young men for battle and held armed rallies in various districts to demonstrate their preparedness.[45]

On February 12, 2015, AQAP detonated car bombs targeting the army’s 19th Brigade stationed in Bayhan’s Al-Alya city.[46] The militants looted large amounts of weaponry from the arms depot in the military camp, including tanks and armored vehicles, before escaping to southern Shabwa. With little resistance, the Houthi-Saleh forces then seized control of the city on March 27, 2015.

In the days that followed, the first in a series of clashes broke out in Usaylan district between Houthi-Saleh forces and tribesmen led mainly by the two prominent tribal leaders: Saleh bin Fareed and Awadh bin Oshaim. The Houthi-Saleh fighters overwhelmed the tribesmen and advanced into Ataq on April 9, 2015,[47] causing an exodus of the capital’s inhabitants, who feared that airstrikes by the Saudi- and UAE-led coalition and street fighting would follow. Bahaj, the governor at the time, fled the city as well, taking refuge in Al-Jabal Al-Abyad, his tribe’s stronghold in eastern Ataq district. When the Houthi-Saleh forces pursued him, the governor headed northward to Hadramawt only to die when his car sped past a checkpoint manned by area tribesmen, came under fire and crashed.[48] Meanwhile, Houthi-Saleh forces expanded southward from Ataq, breaking one front after the other. After entering the town of Al-Said in the final days of May, Houthi-Saleh forces blew up the house of Bin Fareed as a tribal gesture of humiliation that the Houthis have repeated throughout the war.[49] The subsequent advance into the neighboring towns of Habban and Azzan proved to be the farthest Houthi-Saleh expansion into eastern Yemen.

The Houthi-Saleh forces’ swift push into Shabwa had benefited from the former president’s co-option of tribal and other local leaders over the years. As a longtime stronghold of Saleh’s GPC party, he had many allies to lean on. However, the takeover of Ataq was short-lived. Coalition-backed troops loyal to Hadi recaptured the capital four months later, placing its security in the hands of government police and military forces, while Houthi-Saleh fighters shifted attention to holding the Bayhan, Usaylan and Ain districts, which cover the Wadi Bayhan region of northwestern Shabwa.[50] The battle for Wadi Bayhan bogged down local tribal fighters and army reinforcements from Hadramawt for two years before the Houthi-Saleh forces finally retreated to Al-Bayda governorate.[51] Houthi-Saleh forces held onto Wadi Bayhan for longer than other parts of Shabwa in part because of the area’s strategic importance to the alliance. It is a gateway to Marib, Al-Bayda and Hadramawt governorates and located near the Balhaf oil pipeline and a major road to Saudi Arabia. Saleh also enjoyed the support of local tribesmen around Bayhan. Although pro-Saleh tribesmen helped ease the entrance of Houthi-Saleh forces, in Bayhan and in southern parts of Shabwa, an abundance of secessionist fighters in southern Shabwa expelled the alliance. A relatively low level of separatist sentiment around Bayhan was another factor working in favor of the Houthi-Saleh forces. However, when the Houthis killed Saleh in December 2017, pro-Saleh tribes including Al-Lahul stopped fighting.

Landmines in the Valley of Bayhan, a Lasting Legacy

Between 2015 and 2017, as government forces gradually regained control of Wadi Bayhan, the retreating Saleh-Houthi forces planted thousands of landmines as a defensive tactic. While the landmines helped delay the anti-Houthi-Saleh forces’ advance, they have remained a threat to civilians long after the battles died down. About 600 people have been killed and 400 permanently disabled from landmine explosions in Shabwa, according to MASAM, a Saudi-funded effort to clear the mines.[52]

Among the most heavily mined areas are Al-Safra, Al-Salaim and Haid bin Aqeel in Usaylan district and in Mafqah, Raidan, Wadi al-Nahir, Dukam and Dhahbaa in Bayhan district. Planted next to roads and houses and in farmlands, the hidden explosives have caused human and economic losses in the region, as many residents have been reluctant to return home and resume their lives.

The first landmine-clearing efforts were conducted by specialists from the Yemeni army and the government’s Yemen Executive Mine Action Center (YEMAC) team. It soon became clear that the task was much bigger than expected. In August 2018, Saudi Arabia created the MASAM demining project, and entered the area as the main partner for clearing explosives in Wadi Bayhan while also deploying teams in other areas of Yemen such as Taiz and Hudaydah governorates.[53]

The huge number of mines combined with the desert topography of Wadi Bayhan has made it difficult for the teams to estimate how long it will take to clear the area.[54] The continuously shifting sands in parts of northwestern Shabwa have buried some mines too deep for metal detectors to sense, only to have them eventually unearthed by heavy winds at a later date.

Follow Them Back to Al-Bayda

The weeks after the Houthi-Saleh alliance unraveled provided government troops an opening to liberate the three strategic districts of Wadi Bayhan in northwestern Shabwa – Bayhan, Usaylan and Ain – through which major roads connect the governorate to Marib and Al-Bayda governorates. With a foothold in Bayhan, Hadi ordered the formation of the Bayhan Military Axis in March 2018, composed of the following brigades:[55]

- 26th Mechanized Brigade, headed by Mofareh Behaibah who is also the general in command of the axis as a whole;

- 19th Brigade, headed by Ali al-Kulaibi;

- 153rd Brigade, headed by Abdulraheem al-Aqeeli;

- 163rd Brigade, headed by Saleh Laqsam; and the

- 173rd Brigade, headed by Saleh al-Mansori.

They fought alongside newly established battalions, including:

- Al-Nasir Battalion, headed by Nasser al-Qohaih, and the

- Bayhan Battalion, headed by Faozi al-Saadi[56]

Responsible for securing Shabwa’s Wadi Bayhan and Marib’s Al-Jubah and Harib districts, the Bayhan axis has made slow but steady advances against Houthi forces in Al-Bayda governorate. Their push into Al-Bayda has centered on the highland districts of Na’man and Nati’, which have strategic importance to the army because the Houthis could use their elevation to launch attacks into the lower areas of government-controlled Wadi Bayhan. However, the threat of landmines and the fact that the Houthis control uphill positions have made advances difficult.[57] Troops in the Bayhan axis also lack sufficient weaponry and have experienced delays in the payment of their salaries, according to an officer in the 163rd Brigade.[58] Clashes in Na’man and Nati’ have disrupted residents’ livelihoods, prompting an IDP exodus into Shabwa.[59]

The ‘Elites’ and the ‘Legitimates’ Fighting for the Same Job

The Fall of AQAP

With the support of United States military drones,[60] the Hadi government launched two major campaigns to remove AQAP from southern governorates, including Shabwa, in 2012 and 2014. Both of those attempts succeeded in temporarily driving the militants out of certain areas. The rise of the UAE-trained and equipped Shabwani Elite forces starting in late 2016 has so far proven to be the most effective effort to weaken AQAP and its local affiliate, Ansar Al-Sharia, in the governorate.[61] The Shabwani Elite forces were recruited from the tribal communities in which AQAP was operating, similar to the popular committees in Abyan that Hadi had funded and equipped starting in 2012.[62] However, in contrast to Abyan’s popular committees, the Shabwani Elite forces benefitted from better training and equipment, regular pay and greater numbers. The Shabwani Elite also coordinated closely with US and Emirati counterterrorism forces, which included backing with airstrikes.

The Shabwani Elites’ battle against AQAP escalated dramatically in 2018. In January of that year, AQAP carried out its deadliest suicide attack against the counterterrorism forces, killing 20 Shabwani Elite members at a checkpoint near Ataq. In the months that followed, AQAP fighters were chased into neighboring Al-Bayda governorate. However, with the Shabwani Elite disbanded after August 2019 and the broader civil war still in full swing, it’s unclear whether AQAP will attempt to reassert itself in Shabwa.

The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) tracked the rise and fall of AQAP in Shabwa by mapping the group’s attacks – alongside counterterrorism operations by the US and UAE-backed Shabwani Elite – in the governorate since late 2016. ACLED reported a sharp decline in AQAP activity in 2019, which coincided with the steady rise of the UAE-trained Shabwani Elite. By early 2019, it found AQAP activity had decreased markedly and the Shabwani Elite had established a strong presence in the governorate stretching from Balhaf port in the southeast to Merkhah al-Sufla district in the northwest.[63]

The rise of the UAE-trained counterterrorism forces also created new frictions with government forces in Shabwa, which are part of the internationally recognized government’s Third Military Region in neighboring Marib governorate. On the one hand, the Shabwani Elite proved effective at fighting AQAP while also helping prevent Houthi incursions into the governorate. On the other hand, large numbers of the Shabwani Elite gravitated toward the pro-secession STC, which had been calling for the removal of government forces from all southern lands, including Shabwa.

To further that objective, the STC increasingly pushed the narrative that government forces in Shabwa were northerners affiliated with the Islah party, whose priority was maintaining control of the governorate’s oil resources. STC President Aiderous al-Zubaidi has repeatedly called for the “liberation” of Shabwa and oil-rich areas in northern Hadramawt governorate from the “scourge of terrorism and occupation.”[64] On May 18, 2019, Al-Zubaidi convened a meeting of “all commanders” of southern forces, which up until that point had been loosely affiliated militias armed and equipped by the UAE to fight AQAP and the Houthis. A list of decisions issued at the meeting included unifying the command and control of the forces and creating a unified and integrated operations room for all southern security and military forces.[65] In other words, the Shabwani Elite and other UAE-backed militias formalized their relationship with the STC.[66]

August 2019: Showdown in Shabwa

The mutual antagonism between the STC and the Hadi government came to a head in the summer of 2019.[67] On June 19, altercations between Shabwani Elite forces and government army brigades in Ataq quickly escalated into a battle for control of the city, during which the STC issued a statement rejecting “every northern military presence” in the governorate, demanding the Shabwani Elite and police take over security in the capital and calling for demonstrations there.[68] In a matter of days, two army brigades and the Shabwani Elite’s Fourth Brigade, all stationed around Ataq, squared off inside the city amid reports of an assassination attempt on one of the army commanders and oil pipeline attacks. By June 24, tribal mediators had intervened to negotiate the withdrawal of forces from both sides from the city and protesters turned out in the streets in support of the Shabwani Elite.[69]

Tension remained high, but Shabwa’s capital remained largely peaceful until mid-August, when the UAE-backed Security Belt forces helped the STC seize control of the interim capital Aden. Building on this momentum, Security Belt forces overran Hadi’s troops in neighboring Abyan governorate while the Shabwani Elite attempted to dislodge government troops that had returned to Ataq. However, the attempt by Shabwani Elite brigades to capture the governorate’s capital was roundly reversed by the third week in August, as army reinforcements from Marib overwhelmed the pro-secession fighters. Further, the Shabwani Elite forces were not unified behind the decision to wrest control of Ataq from the army, as the Third and Sixth brigades refused to take part in the fighting.[70] A variety of factors appear to have played into their decision, including wariness of another direct confrontation with government forces following the June standoff, and potentially disrupting their territorial hold on the oil-producing and oil-transport areas.[71] Furthermore, the battle for Ataq would have pitted members of the Awaliq tribe against each other, given they held leadership roles and were in the rank-and-file of the Shabwani Elite’s Third Brigade as well as in government brigades in and around Ataq.[72]

The events of August marked a key turning point in the relationship between the Shabwani Elite and the government forces, and a potentially game-changing moment in the broader war. In a report published in January 2020, the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen noted that after Security Belt forces and some Shabwani Elite factions publicly sided with the STC, “these forces are possibly more focused on solidifying their territorial control than fighting terrorism.”[73] Had the pro-STC forces seized control of Shabwa, they also would have been in a strong position to advance into oil-rich Hadramawt and Al-Mahra governorates and potentially control all of southern Yemen.[74] In this way, Shabwa acts as a geographical buffer zone protecting the two governorates.[75]

Shabwa and the Gulf Countries

What the Saudis Have and Haven’t Done; UAE Hasn’t Given Up Yet

Saudi Arabia has played less of a role in Shabwa than in other governorates both militarily and in terms of providing humanitarian and development aid. That is because the Saudis focused on northern Yemen from the outset of the Arab coalition’s involvement in the war and Abu Dhabi took responsibility for southern governorates.

However, Saudi Arabia has maintained a military presence in Aden, northern Hadramawt, Socotra and Al-Mahra for years, and the kingdom has launched numerous aid projects around the country, particularly in Al-Mahra.[76] For a brief period beginning in November 2018, the Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program for Yemen provided Shabwa with fuel aid shipments for electricity generation and water trucks for distributing water in rural areas.[77] However, many projects, including the rebuilding of the main hospital in Ataq that was targeted by coalition airstrikes in 2015, have not been pursued.

When the UAE announced a broad military drawdown in Yemen in the summer of 2019, it began handing off many of its military activities in southern Yemen to Saudi Arabia. Still, the UAE has kept some forces at Balhaf and Al-Alam camps to continue counterterrorism operations in the area.[78]

Following the August 2019 battles between the STC and Hadi’s government, Saudi Arabia mapped out a plan in what became known as the Riyadh Agreement to incorporate the STC and its allied forces into national governance. Signed by the government and STC in November 2019, the power-sharing deal has accomplished virtually nothing amid disputes over the order in which its economic, military and political provisions should be implemented. Saudi officials claimed to have made a breakthrough on that front in August 2020, after Hadi’s appointment of former Shabwani governor Lamlas as the new governor of Aden, but momentum slowed later that month. The STC briefly withdrew from implementation talks before discussions resumed in September toward forming a unified cabinet.

Conclusion

Shabwa governorate has experienced tremendous changes in the past five years, coming under the control of a variety of warring groups. It has witnessed progress despite the turmoil in the form of development projects, a restoration of some public services and improved security — all made possible by securing a degree of financial autonomy in the absence of a strong state.

Yemen’s warring parties and Shabwanis, however, have widely differing views about the governorate’s proper identity and its future. To the STC, Shabwa is the southern governorate lost to the “northerners”; for Hadi’s government, Shabwa is the southern governorate that chose unity. Should the Houthis succeed in overpowering coalition-backed government forces in neighboring Marib, which has been the rebels’ top military objective in 2020, taking control of Shabwa’s oil and gas infrastructure would be a logical next step. Meanwhile, Al-Qaeda, while currently active only in remote areas in Al-Bayda, has proven resilient over the years, and reluctant to leave areas in which it has operated. Amid these competing pressures, Shabwa’s continued stability remains tenuous until broader political settlements among the warring parties are reached.

*Editor’s Note: A previous version of this report misstated when President Hadi ordered the formation of the Bayhan Military Axis. The correct month was March 2018. Correction made on 2021-11-15.

Majd Ibrahim is a humanitarian worker and researcher on the Yemeni conflict and economic issues. He tweets @majd_gawdat.

Nasser al-Khalifi is a Yemeni journalist, human rights activist and researcher on conflict and peacebuilding issues.

Casey Coombs is a freelance journalist and former managing editor of Almasdar Online English. His work focuses on Yemen, where he was based from 2012 to 2015. He tweets @Macoombs.

This paper was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies with the Oxford Research Group, as part of Reshaping the Process: Yemen program.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Oxford Research Group (ORG) is an independent organization that has been influential for nearly four decades in pioneering new, more strategic approaches to security and peacebuilding. Founded in 1982, ORG continues to pursue cutting-edge research and advocacy in the United Kingdom and abroad while managing innovative peacebuilding projects in several Middle Eastern countries.

Endnotes

- “Population projections (2005 to 2025),” Central Statistical Organization, July 21, 2010, http://cso-yemen.com/content.php?lng=arabic&id=553. In 2004, the last time a census was carried out in Shabwa, the governorate’s population was about 471,000, representing less than 2 percent of Yemen’s population.

- By contrast, much of the population of Yemen’s northwestern highlands are Zaidi Shia.

- Laura Chiarantini, Marco Benvenuti, “The Evolution of Pre-Islamic South Arabian Coinage: A Metallurgical Analysis of Coins Excavated In Sumhuram (Khor-Rori, Sultanate of Oman),” Archaeometry 56(4), August 2014, t.ly/f9sW; Charles Schmitz, Robert D. Burrowes, Historical Dictionary of Yemen, (Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 25.

- “Entire Jewish Community of Habban in Arabia Leaves for Aden for Transfer to Israel,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, August 7, 1950, https://www.jta.org/1950/08/07/archive/entire-jewish-community-of-habban-in-arabia-leaves-for-aden-for-transfer-to-israel

- As the British withdrew, competing independence movements – the Arab nationalist Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen (FLOSY) and the communist National Liberation Front (NLF) – fought for control of the newly liberated south. The NLF emerged victorious and formed what became the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY). The new state overran existing rulers in the south, including those in Shabwa, seizing their lands and causing some of them to flee. See Peter Salisbury, “Yemen’s Southern Powder Keg,” Chatham House, March 2018, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2018-03-27-yemen-southern-powder-keg-salisbury-final.pdf

- For a review of this history, see Abdulghani Al-Iryani, “The Riyadh Agreement Dilemma,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 9, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/10311

- Charles Schmitz, Robert D. Burrowes, Historical Dictionary of Yemen, (Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 25.

- Shabwa currently produces 8,000-9,000 barrels per day, which represents about 20 percent of national production. Yemen’s overall oil reserves stand at about 3 billion barrels. Interview with Ali Khairan, general director of the Yemeni ministry of oil and minerals Shabwa branch on August 5, 2020.

- Helen Lackner, Yemen in Crisis: Road to war, (London: Verso, 2019), 219.

- “Baseline conflict assessment in Marib, Aljawf, Shabwa, and Albaidah governorates,” Partners Yemen and Partners for Democratic Change International, 2011.

- The highest concentrations of IDPs in Shabwa are in Ataq, Bayhan and Usaylan districts. Interviews with IDP aid workers in Shabwa in August 2020.

- “South Yemen’s Oil Resources: the Chimera of Wealth,” Central Intelligence Agency, 1988, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP89S01450R000500500001-7.pdf

- “Yemen’s gas sector, ”Yemeni Ministry of Oil and Minerals, http://mom.gov.ye/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=50&Itemid=2

- The consortium’s major shareholders are as follows: Total 39.6 percent, Hunt oil 17.2 percent, Yemen Gas Co. 16.7 percent, SK Energy with 9.6 percent, Korea gas Corp 6 percent, Hyundai Corp. 5.9 percent and the Yemeni Social Security and Pension Authority 5 percent. Ibid.

- “Project overview,” Yemen LNG Company, http://yemenlng.com/ws/en/go.aspx?c=proj_overview; Warren R. True, “Yemen LNG yields first production into glutted market,” Oil and Gas Journal, October 15, 2009, https://www.ogj.com/pipelines-transportation/lng/article/17277276/yemen-lng-yields-first-production-into-glutted-market

- Interview with Ali Khairan, deputy to the director general of the Shabwa branch of the Yemeni Ministry of Oil and Minerals on August 5, 2020

- “Austrian firm boosts Yemen oil production,” MEED, November 20, 2018, https://www.meed.com/austrian-firm-boosts-yemen-oil-production/

- Marib’s Block 18 oil is currently being trucked to Shabwa’s Block 4 and then pumped through existing pipelines to Shabwa’s Al-Nashimah port, as Balhaf remains out of operation. “Transporting crude oil from Marib to Shabwa in preparation for its export (photos),” Al-Watan Al-Adania, October 16, 2019, https://www.alwattan.net/news/91965

- The Southern Movement seeks economic and political change for the people in governorates belonging to the former South Yemen, including Shabwa. Stephen Day, “The Political Challenge of Yemen’s Southern Movement,” Carnegie Papers, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/yemen_south_movement.pdf

- Interview with Naji al-Sammi, a key figure in the 2011 protest movement and an adviser to the current Shabwa governor, August 10, 2020.

- Saleh appointed Mujawer prime minister in 2007.

- Salah Suwaid Bawadh, “Governors of Shabwa from 1967 to 2020,” Crater Sky, July 1, 2020, https://cratersky.net/posts/42860; Interview with the head of Shabwa’s local council, Abdo Rabbu Hishlah, on July 22, 2020.

- Interview with Yemen analyst Ammar Aulaqi on September 22, 2020.

- Hakim Al-Masmari, “Houthi abduction prompts Yemen to turn off oil taps,” The National, January 18, 2015, https://www.thenational.ae/world/houthi-abduction-prompts-yemen-to-turn-off-oil-taps-1.111045

- “Yemen’s Houthis form own government in Sanaa,” Al-Jazeera, February 6, 2015, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2015/02/yemen-houthi-rebels-announce-presidential-council-150206122736448.html

- Hadi appointed Lamlas governor of Yemen’s interim capital Aden in mid-August 2020, marking the first step in the formation of a power-sharing government outlined in the Riyadh agreement.

- It’s unclear when the 20 percent share was negotiated, but it was during bin Adio’s time in office.

- “Shabwa governor says oil sales reach $31 million at opening of college research labs,” Al-Masdar Online English, January 26, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/282; “Shabwa governor: a year has passed since the first oil tanker was exported, and here are the results,” Crater Sky, July 17, 2019, https://cratersky.net/posts/19734

- Interview with Abdurabah Hishlah, head of the local councils on July 22, 2020; Interview with Ali Khairan, general director of the Yemeni ministry of oil and minerals Shabwa branch on August 5, 2020.

- Long-delayed development projects include construction of the Hatib-Mudiyah road creating a shorter route from Ataq to Aden, and construction of the University of Shabwa.

- Interview with STC representative in Shabwa, Ali Mohsen Soleimani, on August 18, 2020.

- “What is the truth of the resignation of Shabwa governor?” Al-Masdar Online, March 6, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/article/what-is-the-truth-of-the-resignation-of-shabwah-governor

- Interview with a relative of Bafayadh, September 26, 2020.

- “Security Forces in Shabwa Announce the success of a security campaign to restore all state buildings,” Al-Mahra Post, February 22, 2020, https://almahrahpost.com/news/15391

- Interviews with Kholud Yahia, director of girls’ education at the Ministry of Education branch in Shabwa on August 5th 2020; Thekra Abu Baker, a female local community leader in Shabwa on August 8, 2020; Dr. Ali Al-Habir, Shabwani academic on August 9, 2020; and Dr. Mohammed Laswar, vice dean of the college of education branch of Aden’s University in Shabwa on August 9, 2020.

- Casey Coombs, Fernando Carvajal, “Yemen’s UAE-backed forces take on life of their own amid Emirati drawdown,” Middle East Eye, July 10, 2019, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/yemens-uae-backed-forces-take-life-their-own-amid-emirati-drawdown

- “Shabwa governor accuses UAE of financing chaos and exploiting people,” Al-Masdar Online English, February 5, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/309

- Rumors at the time of their formation suggested that the brigades were going to be named after their member tribes. For example, the Third Brigade would have been called the Awlaki Elite forces.

- “Violent confrontations between Emirati-backed forces and Yemeni tribes,” Al-Khaleej Online, January 4, 2019, ibit.ly/v9qt

- “Shabwa governor calls on President Hadi to stop “the tampering and provocation of UAE forces,” Al-Masdar Online English, December 13, 2019, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/175

- Interviews with two now-former members of the Shabwani Elite forces, an officer and an enlisted soldier, in September 2020.

- Emile Roy, Andrea Carboni, “Yemen’s Fractured South: Shabwah and Hadramawt,” ACLED, May 9 2019, https://acleddata.com/2019/05/09/yemens-fractured-south-shabwah-and-hadramawt/

- “Riyadh Agreement: Full text of the Yemeni government, STC agreement (unofficial translation by Al-Masdar Online),” Al-Masdar, November 6, 2019, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/58

- “With the support of the Shabwa tribes, the Shabwani Elite Forces continue the campaign to prevent weapons in the governorate,” Al Ghad Al Mashreq Channel, October 3, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ctcq2PL-g5c

- “The largest tribe in Shabwa is an armed force to repel the Houthis,” Al-Jazeera, February 19, 2015, ibit.ly/EJzt; “The tribes of Shabwah in Salim point prepare to confront the Houthis in Beihan district,” YouTube, March 28, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iI5fLiUWgOU

- “Ansar al-Sharia in Yemen announces its takeover of the camp of the 19 Infantry Brigade in the Governorate of Shabwa,” The New Khalij, February 12, 2105, ibit.ly/XZ0C

- Mohammed Mukhashaf, “Yemen’s Houthis Seize Provincial Capital Despite Saudi-Led Airstrikes,” June 9, 2015, ibit.ly/9nF0

- Interview with Yemen analyst Ammar Aulaqi on September 22, 2020.

- “Yemen’s Houthis blow up ex-president Saleh’s house,” Reuters, December 4, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-house/yemens-houthis-blow-up-ex-president-salehs-house-idUSKBN1DY159; Ali Mahmood, “Fierce fighting in south Yemen after Houthi rebels blow up tribal leader’s home,” The National, February 11, 2019, https://www.thenational.ae/world/mena/fierce-fighting-in-south-yemen-after-houthi-rebels-blow-up-tribal-leader-s-home-1.824649; “Ibb tribesmen use Houthi tactics to settle scores,” Al-Masdar Online English, February 3, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/local/303

- “Letter dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council,” Security Council, January 27, 2020, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3850088?ln=en

- Interview with Commander Salem Ali al-Khalifi, staff major of the 163rd Brigade, August 9, 2020.

- Interview with a landmine-clearing specialist with MASAM, August 12, 2020.

- By April 2020, MASAM stated that it had cleared more than 160,000 landmines in Yemen. “Demining worker killed by landmine in Taiz,” Al-Masdar Online English, April 21, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/676

- Interviews with landmine-clearing specialists with MASAM, former landmine awareness NGOs employees in Shabwa and locals from Wadi Bayhan districts on August 5, 8 and 12, 2020.

- “Republican decision to form a new military axis that includes five directorates in Shabwa and Marib,” Yemen Shabab, March 17, 2018, https://yemenshabab.net/news/33477

- Interview with Commander Salem Ali al-Khalifi, staff major of the 163rd Brigade, on August 9, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Scott Shane, “Yemen’s Leader Praises U.S. Drone Strikes,” The New York Times, September 29, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/29/world/middleeast/yemens-leader-president-hadi-praises-us-drone-strikes.html; Wasim Nasr, “Yemen: A week after the air strikes, what is happening in Shabwa and Abyan governorates? [AR]” France24, April 29, 2014, https://www.france24.com/ar/20140429

- The UAE created comparable counterterrorism militias drawn from locals in Hadramawt, called the Hadrami Elite, as well as in governorates surrounding Aden, known as the Security Belt forces, around the same time.

- Casey Coombs, “Yemen’s Use of Militias to Maintain Stability in Abyan Province,” CTC Sentinel, February 2013, https://ctc.usma.edu/yemens-use-of-militias-to-maintain-stability-in-abyan-province/

- Emile Roy, Andrea Carboni, “Yemen’s Fractured South: Shabwah and Hadramawt,” ACLED, May 9 2019, https://acleddata.com/2019/05/09/yemens-fractured-south-shabwah-and-hadramawt/

- Media Center of the Southern Resistance Forces, “The second expanded meeting of the leaders of the Southern Resistance,” Facebook, May 18, 2019, https://www.facebook.com/south.media1/photos/a.757733230921137/2606389676055474/?type=3

- “Al-Zubaidi Chairs Extended Meeting of Southern Resistance,” Aden Press, May 18, 2019, http://en.adenpress.news/news/4292

- In June 2019, the Shabwani Elite informed the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen that they “envisage a unification of all southern forces, including the SEF and the Security Belt Forces (SBF).” “Letter dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council,” Security Council, January 27, 2020, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3850088?ln=en

- It is important to note that the STC-Hadi struggle is rooted in a long history of political tensions between the tribes of Al-Dhalea and Lahj governorates (the STC leadership) and those from Abyan and Shabwa (Hadi). For a review of this history, see Abdulghani Al-Iryani, “The Riyadh Agreement Dilemma,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 9, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/10311

- “A statement issued by the expanded meeting of the leaders of the Southern Transitional Council in Shabwa governorate,” Southern Transitional Council, June 22, 2019, https://www.stcaden.com/news/9863

- “Letter dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council,” Security Council, January 27, 2020, p. 77, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3850088?ln=en

- Ibid., 14.

- Ibid., 14-16.

- Interview with Yemen analyst Ammar Aulaqi on September 22, 2020.

- “Letter dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council,” Security Council, January 27, 2020, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3850088?ln=en

- Interview with Yemen analyst Ammar Aulaqi on August 17, 2020.

- Ibid.

- “SDRPY projects factsheet (April 2020),” Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program for Yemen, http://www.arabia-saudita.it/files/news/2020/06/sdrpy_projects_factsheet_april_2020_29_april.pdf

- Interview with Abd Rabbah Hishlah, head of the local councils in Shabwa.

- “Elite and coalition forces move to Al-Alam camp in Shabwa,” Al-Ayyam, July 2, 2020, https://www.alayyam.info/news/896Z0ZKH-NGZAWP-C8A9

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية