Editor’s Note: For security reasons, the Sana’a Center is withholding the name of a Yemeni co-author based in Al-Mahra whose research was crucial to this report.

Editor’s Note: For security reasons, the Sana’a Center is withholding the name of a Yemeni co-author based in Al-Mahra whose research was crucial to this report.

Executive Summary

Although far from the frontlines of Yemen’s civil war, Al-Mahra governorate remains an important battleground for Gulf powers competing for influence in the conflict. A Saudi military buildup in Al-Mahra, purportedly aimed at slowing the flow of Houthi-bound weapons from Iran, reached a tipping point in February when fighting broke out over the mounting restrictions on cross-border trade. The clashes immediately preceded the appointment of a new governor who has been less divisive than his predecessor and has found some success managing anti-Saudi tensions in the governorate.

However, despite the political shakeup and the new direction it signals, numerous competing interests remain at odds on the local and regional levels. This paper focuses on the most recent shifts in these political dynamics — among local and regional players — including the politics behind and impact of southern separatists’ recent gains in nearby Socotra. It looks at how local authorities have handled challenges to Riyadh’s commanding presence and influence, a result of its military dominance as well as its financial support for local tribes and armed groups. In recent months, Mahri customs officials have made formal complaints about Saudi military interference at the Shahin border crossing. Human Rights Watch also has accused Saudi troops of disappearing and torturing Mahris based on alleged ties to Qatar, Omani intelligence and Hezbollah.

Against this backdrop, questions linger over local concerns about Saudi ambitions to build an oil pipeline through Al-Mahra, how Oman’s new sultan will handle the Saudi border buildup and how much influence Qatar and anti-Saudi allies are actually exerting in the governorate.

Introduction

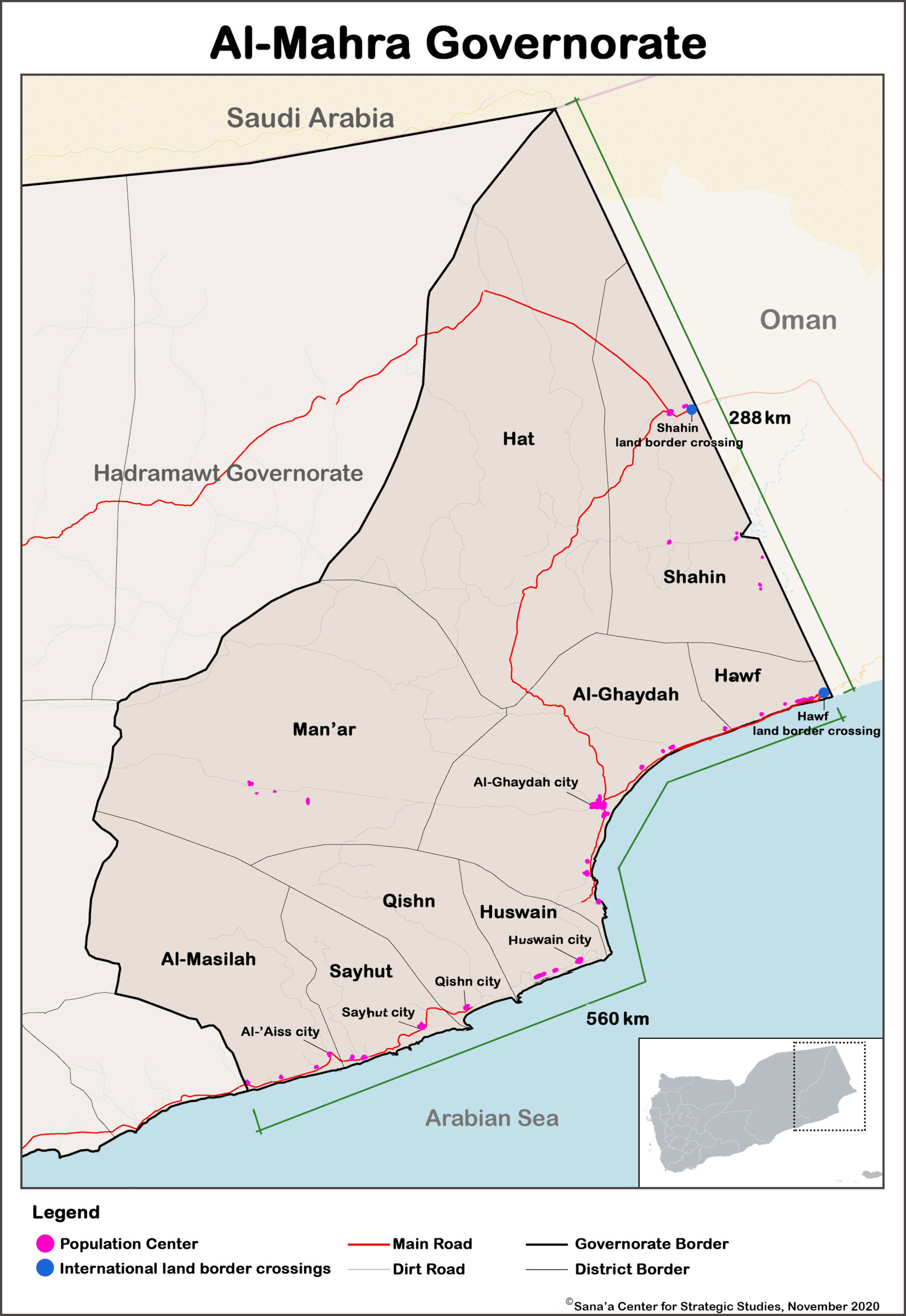

Located at the easternmost end of Yemen, Al-Mahra shares a nearly 300-kilometer border with Oman that extends from the Arabian Sea to Saudi Arabia. Tribes on both sides of the border share a Semitic language separate from the Arabic spoken around them.[1] The governorate spans an area of more than 67,000 square kilometers,[2] making it the second-largest in Yemen after Hadramawt on its western border. Al-Mahra’s main cities, including the capital and largest urban center Al-Ghaydah, are located along the governorate’s 560-kilometer coastline on the Arabian Sea. Current estimates of the governorate’s population vary widely, up to 650,000 people, given that the last official census in the governorate was more than 15 years ago and the latest war has resulted in massive internal population shifts.[3]

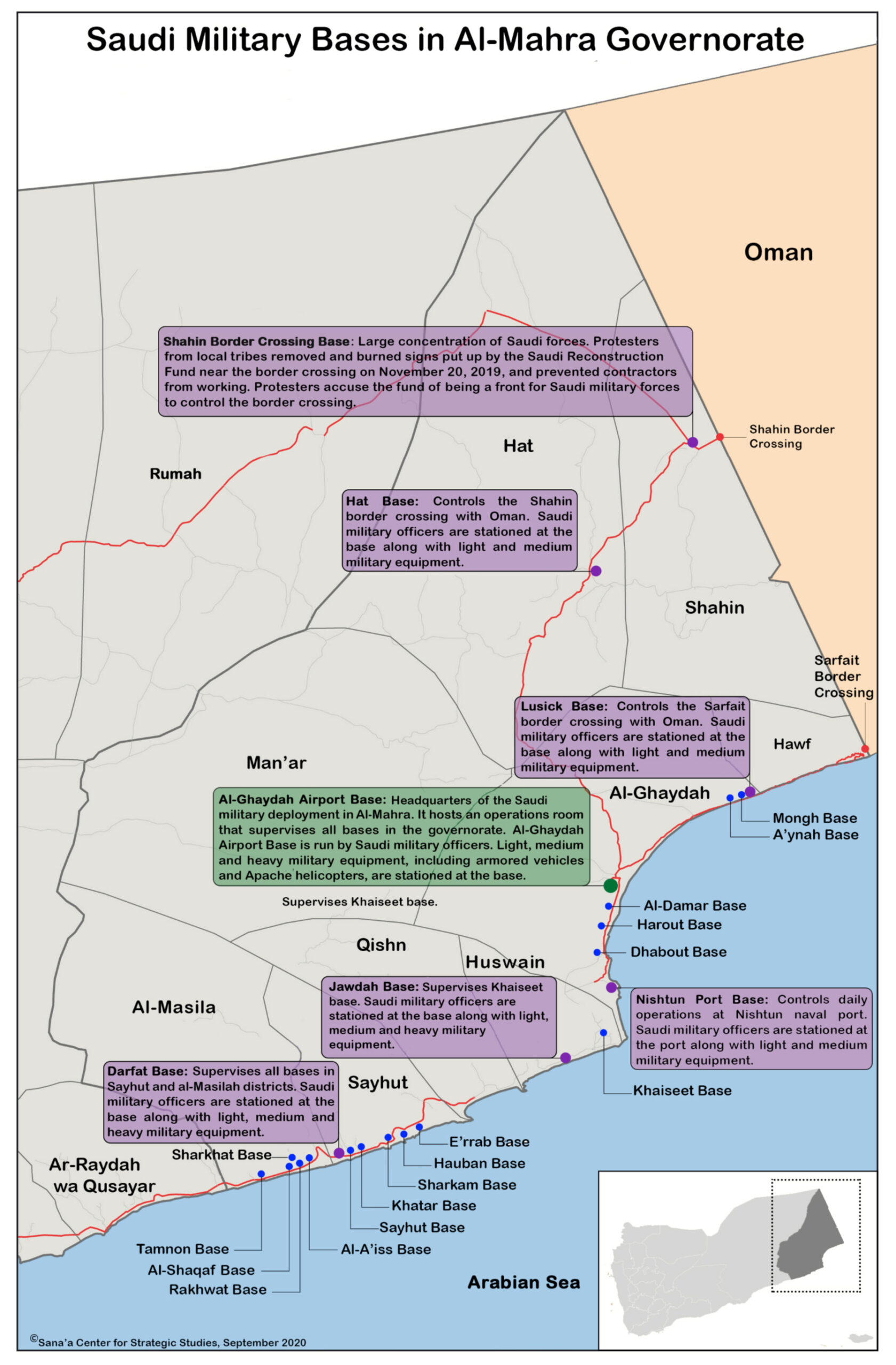

Al-Mahra’s relationship with Saudi forces, who are well-entrenched about three years after entering the governorate, has been tumultuous. Saudi forces occupy sea, air and land ports in the governorate.[4] Local opposition groups had demanded Riyadh pull its troops out of the governorate through increasingly frequent peaceful sit-ins, demonstrations, vigils and occasional violent confrontations.[5] However, on February 17, 2020, a convoy of Saudi forces accompanied by Yemeni forces from the Special Task Force Battalion was ambushed by tribal gunmen on the road leading to Al-Mahra’s Shahin border crossing with Oman. The convoy was part of a patrol tasked with carrying out daily inspections of Al-Mahra’s ports, as part of efforts to prevent the smuggling of military technology from Iran to the Houthi rebels.[6]

The Saudis, who later claimed those involved in the ambush were part of an organized crime and smuggling network, responded to the attacks with Apache helicopter gunships, wounding a number of the suspected militants.[7] While there were no significant casualties from the attacks, the incident underscored how explosive the Saudi relationship had become with local tribesmen who had long complained about interference with cross border trade routes. It once again tested the Saudi presence and precipitated a political shakeup that ushered to power a popular former Mahri governor, Mohammed Ali Yasser, to manage the competing groups.

The new governor was confronted with a major problem in June, when the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) seized control of the Socotra archipelago, which has deep historical ties with Al-Mahra. The island coup, which took place with virtually no resistance from Saudi forces stationed in Socotra’s capital, raised fears among Mahris that the STC could come for their governorate next. These fears were reinforced when a key figure in Mahri politics, Abdullah ben Afrar, threw his support behind Socotra’s new rulers.[8] The Afrar family, descendents of the dynasty that ruled Al-Mahra for hundreds of years starting in the 16th century, quickly replaced Ben Afrar as the head of the family council with his younger brother and reaffirmed its longstanding ties with Oman.[9]

Despite the growing Saudi military buildup in its backyard, Oman has been the most influential foreign power among Mahris, and a prominent mediator in the wider Yemeni conflict. In addition to its border with Al-Mahra, Oman shares cultural, security and economic interests with Mahri tribes that Muscat has nurtured over the years through offering them perks like Omani citizenship, political refuge during times of crisis, monthly salaries and aid projects in the Yemeni governorate. Saudi Arabia has sought influence in Al-Mahra not only through building up its forces in the governorate since 2018, but also through a soft power campaign that mirrors the Omani approach. A leaked document detailing coalition disbursements to armed groups in Al-Mahra indicates Riyadh has bought the loyalty of thousands of tribesmen (See Annex A).

A New Governor and Broader Shifts in the South

On February 23, less than a week after the ambush of Saudi and Yemeni forces, President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi dismissed Al-Mahra’s governor, Rajeh Bakrit, a Saudi loyalist whose time in office coincided with Riyadh’s military buildup and the local frustrations that came with it. In Bakrit’s place, Hadi appointed Mohammad Ali Yasser, who had previously served as Al-Mahra’s governor under Hadi from December 2014 to November 2015.[10] Yasser’s first stint as governor ended after he fell out of favor with the coalition in part for pushing back against UAE plans for a Mahri Elite Force, akin to Emirati-backed paramilitary forces being formed in other southern governorates at the time.[11] With deep roots in Mahri politics and family ties with anti-Saudi powerbrokers in the governorate,[12] Yasser is, however, seen as less divisive than Bakrit and more capable of defusing tension and armed confrontations in Al-Mahra.

Influential leaders in Al-Mahra’s political scene welcomed the news of Yasser’s appointment. Sheikh Aboud Haboud Qumsit, an outspoken critic of Bakrit and a leader of the Oman-backed peaceful sit-in committee of the people of Al-Mahra, which has been leading protests against the Saudi-led coalition presence in the governorate, welcomed Yasser as an “acceptable figure.” He noted, however, that the group would not give up on its aim to end the Saudi “occupation.”[13] Abdullah ben Afrar, who was instrumental in driving Emirati forces out of Al-Mahra in 2017 and helped form the anti-Saudi sit-in committee, showered Yasser with compliments.[14] As the son of the last ruler of the Mahra sultanate and chairman of the General Council of Sons of Al-Mahra and Socotra, a body of tribal leaders formed in 2012, Ben Afrar has grown influential over the past decade in part with the help of Oman. Ben Afrar’s position on the role of Gulf players in the governorate, however, changed dramatically in recent months when he backed the pro-UAE secessionist STC takeover of Socotra.[15] Ali al-Hurayzi, the governorate’s former deputy for desert affairs and a former commander of the border guard, helped build and lead the opposition to the Saudi military presence alongside Ben Afrar. Al-Hurayzi, known for speaking bluntly, was quiet about Yasser’s appointment, but his positions generally align with the sit-in committee when it comes to issues regarding Saudi Arabia.[16]

Yasser was born in Al-Mahra’s easternmost district of Hawf in 1964 and has had a long political career in the governorate. He helped bring the General People’s Congress (GPC) party of Ali Abdullah Saleh to the governorate and was elected president of the party’s Al-Mahra branch in 1995. In 1997, Yasser became a member of the House of Representatives and he was re-elected in 2003 as a representative of the 158th district of Al-Mahra governorate. He was appointed Minister of State in early 2001, and then served as a member of the Council of Ministers until 2007. In the early 2000s, Yasser also served as a member of the presidential committee to solve revenge and political conflicts.[17] In addition to holding a number of leadership positions in Mahri politics, Yasser is known to have good relations with the sheikhs of various Mahri tribes.[18]

Yasser’s Mahri-centric background stands in sharp contrast to his predecessor. Bakrit arrived in Al-Mahra’s capital on a Saudi plane in January 2018 to assume the post of governor. Accompanied by Mahri tribal sheikhs who had been granted Saudi residency in the 1980s, Bakrit had been living in Riyadh, the UAE and Qatar in the more recent years leading up to his return. His only previously known professional experience in Al-Mahra was as a teacher employed by the Ministry of Education prior to 2000.[19]

Bakrit has been accused of corruption, excessive public spending and failing to deposit revenue in the Central Bank of Aden. In July 2019, prosecutors ordered the freezing of transactions from a bank account in which Bakrit was depositing the governorate revenues.[20] On Bakrit’s watch, local authority debts and obligations to contractors and traders reached more than 60 billion Yemeni rials, according to a local authority official who had viewed documents including payment records.[21] Despite these allegations, President Hadi appointed Bakrit as a member of the Shura Council, the upper house of parliament, after dismissing him as governor in February.[22]

An Immediate Test for Governor Yasser

Since taking office in February, Yasser has pushed to unify the governorate’s various political powers and focus on security and the provision of services.[23] But it has proven to be a precarious balancing act. On February 25, two days after Yasser took the helm of Al-Mahra’s local authority, five Yemeni soldiers were killed in another ambush targeting Saudi forces en route to a routine inspection mission at the Shahin border crossing. The deceased soldiers, from the northern governorates of Amran, Ibb and Al-Mahwit, were part of a Special Task Force loyal to former governor Bakrit and paid by the Saudis.[24] It was the bloodiest day of confrontations in Al-Mahra in a year-and-a-half and marked Yasser’s first big test as governor.[25]

The governor asked Saudi forces to refrain from military action and instead give him a chance to handle the situation.[26] The Saudis agreed and Yasser formed a committee to conduct an investigation into the incident and identify the perpetrators and their supporters.[27] Headed by the secretary general of Al-Mahra’s local council, Salem Naimer, the committee was also directed by the governor’s office to disburse 3 million Yemeni rials to the families of each of the Yemeni soldiers killed and 2 million rials to a wounded soldier, who was flown to Saudi Arabia for treatment.[28] Documents seen by one of the authors indicated payment was made to at least one of the families, from local authority funds. The committee’s investigation, however, failed to identify any perpetrators, in part because crime scene evidence had been compromised, according to a member of the committee. The committee member said the governor’s office had been notified of the situation.[29]

Yasser Meets with Leaders of the Sit-In Committee Opposed to the Saudi Presence

Two weeks later, Yasser met with the leaders of the sit-in committee, which had a contentious relationship with the local authority under Bakrit.[30] The committee’s chairman, Sheikh Amer Saad Kalshat, expressed his readiness to work alongside the local authority under Yasser and the Hadi government. Kalshat rejected any armed formations outside state institutions, alluding to armed groups that Bakrit had formed[31] in line with Saudi Arabia’s security agenda.[32]

Yasser denounced the military formations, and has given orders to restructure them and include them under the leadership of the Ministry of Defense and Interior, according to officials close to the governor. Saudi Arabia still pays the salaries of these soldiers, though the officials said the payments are sporadic, sometimes skipping months at a time, unlike the Emirates, which paid the soldiers’ salaries regularly each month.[33] Yasser held another meeting with the sit-in committee to discuss the Saudis’ seizure of a boat loaded with weapons allegedly arriving from Iran and destined for Houthi fighters. After detaining the boat in Nishtun port in April, Saudi forces temporarily expelled about 20 Yemeni port protection forces loyal to the Ministry of Defense and brought in other Yemeni forces the kingdom had trained, according to a port official.[34]

A spokesman for the sit-in committee, Ali Mubarak Mohamed, said Yasser has brought some of the Saudi-loyal military forces under the leadership of the security committee of Al-Mahra’s local authority. “While the governor has tried to reduce tensions, the Saudi army still has control over the ports and remains in the province,” he said.[35]

At times, the sit-in committee has criticized Yasser for failing to respond firmly against Saudi improprieties, including accusations that Saudi forces threatened the head of Shahin border crossing.[36] The governor also has failed to prevent violations by the sit-in committee, such as bringing weapons to protests. Meanwhile, the Hadi government has done little to support Yasser as governor since his appointment.

Yasser Urges Political, Tribal Groups to Stand Against STC Moves in Socotra

A major test for the new governor’s agenda to prioritize security, stability and unity came in June, when the STC wrested control of Socotra’s capital from the internationally recognized Yemeni government. Due to the historical relationship between Al-Mahra and the Socotra archipelago, which together made up the former Mahra sultanate, Al-Mahra’s local authority expressed fears that the STC takeover of the main island could be a preview of the separatists’ intentions for the Mahri capital, Al-Ghaydah. The leaders of the sit-in committee and various political groups in Al-Mahra followed with great concern the UAE-backed STC’s takeover of the island of Socotra with the complicity of Saudi forces in June.[37]

Yasser held meetings with tribal and political leaders in the governorate, including the General Council headed by Ben Afrar and the local branches of the STC and the Islah party. In mid-July, the local authority formed a preparatory committee headed by the former three-time governor Mohammed Abdullah bin Kuddah to hold an expanded meeting of all tribal and political components in Al-Mahra to sign a code of honor between the various components to maintain the security and peace of the governorate and spare it armed conflict.[38] The STC chose not to participate in the pact and Ben Afrar withdrew soon after it formed.[39]

The sit-in committee reiterated its rejection of the STC’s destabilizing effects on security and stability in Socotra and held the Saudi-Emirati alliance responsible for the bloodshed and the fragmentation of the social fabric of the peaceful island. When the STC declared self-administration in April, Al-Mahra’s local authority under Yasser joined other southern governorates that called the move a coup d’état against the internationally recognized government and the Riyadh Agreement, which was negotiated in November 2019 to create a power-sharing government in southern Yemen by incorporating the STC into the national institutions under Hadi.[40] The agreement was created after the STC seized control of the interim capital Aden and ejected forces loyal to the Hadi government in August 2019, before attempting to take over neighboring Abyan and Shabwa governorates.

A spokesman of the sit-in committee emphasized the group’s opposition to the STC in a post on his personal Facebook page in May.[41] “We in the eastern governorates of Al-Mahra and Socotra are not represented by those voices in the southern governorates calling for chaos and sabotage, and spreading racism and hate speech in implementation of an Emirati-Saudi plan,” he wrote.

Ben Afrar Breaks from Tribal Pact, Supports STC

By early July, Mahri groups opposed to the Saudi-led coalition were growing increasingly hostile to Ben Afrar, who had been signaling support for the Gulf powers’ actions in the area since returning from a September 2019 meeting in Saudi Arabia with the kingdom’s deputy defense minister, Prince Khalid bin Salman.[42] In late June, for example, it was revealed that a brigade loyal to Ben Afrar would join the UAE-backed STC in Socotra following the secessionist group’s takeover of the island.[43] In a statement, Al-Hurayzi declared that “the General Council no longer represents the Sons of Al-Mahra and Socotra and [Ben Afrar] is no longer the leader of this nation in this circumstance,” accusing him of “standing by the occupation.”[44]

The Afrar family seemed to agree with Al-Hurayzi. On July 10, they appointed a new head of the family council, replacing Abdullah ben Afrar with his younger brother, Mohammed Abdullah ben Afrar.[45] Within 48 hours of the announcement, which emphasized the importance of preserving close ties with their “sister Sultanate of Oman,” activists launched a Twitter campaign targeting the outgoing Ben Afrar, calling him a traitor for supporting the STC.[46]

Two weeks later, tribal gunmen loyal to Al-Hurayzi stormed a gathering of STC loyalists who were celebrating the implementation of the separatists’ declaration of self-administration. The next day, the local authority’s security committee held an extraordinary meeting to discuss how to prevent parties from holding events that threaten to destabilize the security of the governorate and turning it into a battleground.[47] STC leadership rejected the security committee’s decision and held the event in front of its office in Al-Ghaydah. In response, the security committee closed the entrances to the governorate and barred demonstrations in the capital.[48] The General Council, headed by Ben Afrar, criticized Al-Mahra’s security committee for trying to prevent the STC demonstrations.[49]

Gulf Powers Continue to Compete for Influence in Al Mahra

Oman’s Role: Al-Mahra Presents a Foreign Policy Test for New Sultan

Oman has long considered Al-Mahra an extension of the sultanate, both geographically and demographically. As a result, the governorate has factored into Muscat’s economic and national security considerations. Oman has maintained the relationship through a soft power policy by providing Al-Mahra with logistical support, development assistance on a regular basis and by facilitating commercial trade and the movement of Mahris to and from Oman. Al-Mahra’s economic importance to the sultanate grew early on in the war, when the Saudi-led coalition restricted Houthi imports through the port of Hudaydah among others, prompting many traders to start using land routes through Oman as an alternative. Bin Kuddah, Al-Mahra’s governor at the time, capitalized on the Gulf blockade by lowering customs fees and beefing up customs clearance capacity at the Shahin land port, which magnified the importance of the Oman-Yemen border as a trade corridor.[50] Customs revenues from Shahin land port have seen an almost six-fold nominal increase between 2012 and 2019, rising from about 7 billion Yemeni rials prior to the war to 40 billion rials.[51] However, with the depreciation of the rial over the same time period, the real value increase was slightly more than double, from US$32.6 million to roughly US$65 million. In late 2017, the Saudis intensified their troop buildup in Al-Mahra and extended the Houthi blockade to Mahri land, air and sea ports. Saudi forces introduced new security measures, including the installation of an x-ray scanning machine at Shahin border crossing, with the goal of curbing arms smuggling to the Houthis.[52]

Oman has also fostered relations with prominent tribal and other leaders in Al-Mahra, granting citizenship to figures like Ben Afrar and Al-Hurayzi. Bin Kuddah was welcomed by Oman as a political refugee following Yemen’s civil war in 1994. Many of the individuals Oman has supported in Al-Mahra were known to have opposed Saudi Arabia’s military presence in the governorate.[53] At the same time, Oman has maintained productive relationships with all of the belligerents in Yemen’s war. The Houthis’ delegation for political negotiations resides in Muscat, which made the capital an appropriate venue for secretive Saudi-Houthi talks in the latter half of 2019.

Governor Yasser underlined Al-Mahra’s long standing relationship with Oman a few weeks after taking office. In an interview with reporters, Yasser said he had told the leadership of the Saudi-led coalition that “the support of the brothers in the sultanate preceded your (the coalition’s) support for Al-Mahra, and they stood with us in many situations and events.”

The policy of Oman’s new leader, Sultan Haitham bin Tariq Al-Said, who in January 2020 succeeded the longtime ruler Sultan Qaboos bin Said, became somewhat clearer in late August with the overhaul of his cabinet. Oman, which has recently taken economic hits from historically low oil prices, the coronavirus pandemic and disruptions on its border with Yemen, may be under greater pressure to compromise with Riyadh. As part of the new cabinet, Haitham replaced Oman’s foreign minister of 23 years, Yusuf bin Alawi, throwing into question whether the move will impact Muscat’s relations with neighboring UAE, Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

Bin Alawi’s successor, Badr bin Hamad al-Busaidi, joined Oman’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the late 1980s and worked his way up through the ranks. The new foreign minister is of the Al-Busaidi tribe, from which the royal family also hails, although the minister is not a royal. American diplomats who have served in the region have found him likable and competent, according to Yemen analyst Elana DeLozier. As a firm believer in Oman’s policy of neutrality and the promotion of tolerance, he is likely to stay the course on Oman’s foreign policy, DeLozier suggested, adding that this neutrality policy means that Oman is in a position to advise the Houthis while also meeting regularly with Saudi Arabia — a role that will be critical if peace talks between any of the parties in Yemen take place.[54]

Saudi Arabia Strengthens its Hand: Pays Loyalists, Tightens Control

In addition to the intimidation factor inherent in Saudi Arabia’s increased military presence, Riyadh funds salaries of fighters, officials and tribesmen in Al-Mahra. It has maintained its presence at the Shahin border crossing and the Nishtun seaport and has prohibited dozens of items[55] – including solar panels, four-wheel drive vehicles, some types of fertilizers and boat parts – from entering through them; a small number of Saudi soldiers are stationed near each port, monitoring customs clearances and sometimes inspecting cargo themselves.[56] At the same time, following in the footsteps of Oman, the kingdom has pursued a multi-pronged soft-power campaign in the governorate by launching aid projects.

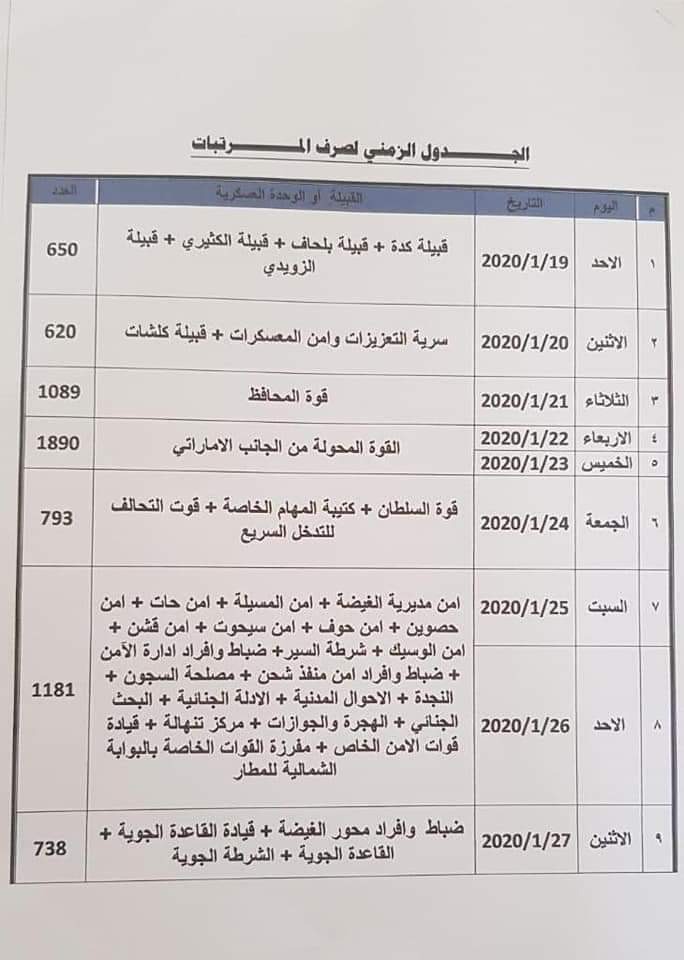

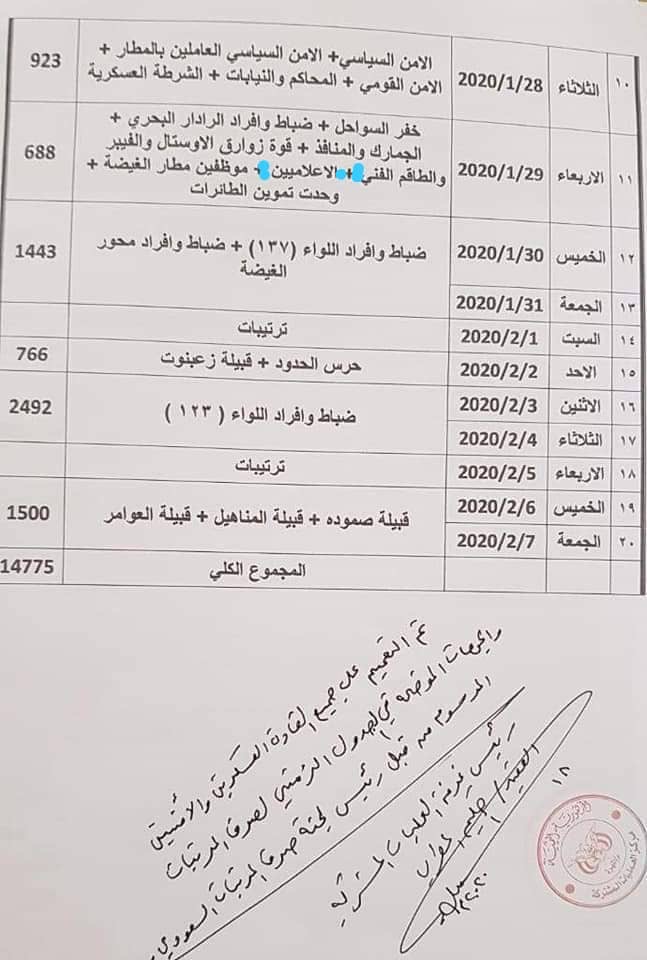

Saudi Arabia also has thousands of tribesmen on its payroll, according to a document obtained by the authors and confirmed by a local official that detailed the Saudis’ disbursement of salaries to armed groups in Al-Mahra during a roughly three-week period in January and February 2020.[57] Such support has fostered the most significant divisions in Mahri tribal society since the governorate was formed in 1967 and given rise to competing armed tribal groups.[58] Among those groups indicated to receive salary disbursements between January 19 and February 15, 2020, were 650 members of the Kuddah, Balhaf, Kathiri and Zuwaidi tribes, 1,500 members of the Samoudah, Manahil and Al-Awamer tribes as well an unspecified number of members of the Kalashat and Zaabnout tribes. It also listed payment to 1,890 members of forces transferred from UAE oversight. Other fighters, including members of Saudi special task forces, were listed as well as security personnel in districts throughout the governorate and at air and sea ports, and police, judges, and members of the media. The document was signed by Hakeem al-Matari, head of the joint operations room for coalition and Yemeni forces in Al-Mahra (see translation, Annex A). In July, a letter signed by 63 tribal sheikhs — including from eight of the nine tribes specifically identified in the January-February payment disbursement document — reaffirmed their backing of President Hadi and the Saudi-led coalition and thanked both for their “support for Al-Mahra governorate in all services and basic areas (see Annex B).[59]

Figure 1: Schedule for Salary Disbursements[60]

The kingdom’s aid efforts in Al-Mahra are most visible through the work of the Saudi Program for the Development and Reconstruction of Yemen (SDRPY). According to an SDRPY projects fact sheet through April 2020, Al-Mahra and Socotra feature prominently in Saudi aid efforts, while these two governorates are the only ones that have been spared the violence of the wider conflict.[61] They are also governorates in which Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been accused of pursuing interests that are unrelated to the coalition’s intervention in the civil war; namely, Riyadh’s purported plans to build an oil pipeline through Al-Mahra and Abu Dhabi’s apparent interest in using Socotra as a military foothold near the Gulf of Aden shipping corridor.[62]

In Al-Mahra, the SDRPY’s development work covers a broad scope, including a dialysis center, renovation of Al-Ghaydah’s hospital, airport and seaport, linking water sources to Al-Ghaydah, providing fishing boats and refrigerators to Mahris and the construction of a number of security buildings for counterterrorism, border security and coast guard operations.[63]

While development projects are generally welcomed across Al-Mahra, many Saudi commitments in Al-Mahra have not been implemented, including the long-promised King Salman Medical and Educational City. A leader of the General Council of the Sons of Al-Mahra and Socotra said that Mahris are waiting for the Saudis to follow through on their promises.[64]

Parallel to this soft-power approach aimed at winning Mahri trust, the kingdom has tightened control over Al-Mahra’s air, land and seaports as part of its stated goal of curbing smuggled goods that benefit the Houthi war effort. Saudi forces have also trained and supported coast guard forces with weapons and supplies and deployed surveillance equipment and towers along the coast of the governorate.

The UN Panel of Experts on Yemen has concluded in annual reports that some of the main smuggling routes through which the Houthis have obtained advanced weaponry, including drone and missile parts from Iran, likely pass through Al-Mahra.[65] A representative of the General Council of the Sons of Al-Mahra and Socotra said that while the Saudi military buildup has reduced the smuggling of weapons to the Houthis, Al-Mahra’s coasts are too long and its deserts too wide to stop the flow of illicit arms.[66] However, the deputy head of the anti-Saudi sit-in committee denies that the Houthis have received such shipments from smuggling routes via Al-Mahra, claiming the border crackdown is an excuse by Riyadh to occupy Al-Mahra in order to further its agenda to build an oil pipeline through the governorate.[67]

Other Saudi opponents in the governorate view the situation similarly, seeing the kingdom’s military buildup as a front for the strategic regional goal to build a pipeline through Al-Mahra to bypass Iranian and Houthi threats to oil shipping lanes in the Strait of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandab chokepoints, respectively. Al-Hurayzi has opposed the alleged plan for the pipeline’s construction for decades.[68]

The views of the sit-in committee and the General Council, however, are more aligned on the prospects of a Saudi oil pipeline through Al-Mahra than most other issues involving the kingdom.

“Saudi Arabia is certainly determined to have a strategic presence in Al-Mahra through economic plans and projects such as the extension of the oil pipeline to the Arabian Sea,” said Ali Mubarak Mahamed, a senior spokesperson for the sit-in committee. “But the Sons of Al-Mahra will only allow this through the right legal frameworks and through the legislative institutions elected by the people.” He implied that the only way the Saudis could realize the oil pipeline was by shelving plans for Saudi soldiers to protect it.[69] In the early 1990s, similar concerns over sovereignty had been the main sticking point in negotiations over the proposed pipeline with former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh, as Riyadh had proposed a four-kilometer buffer zone around the pipeline in which Saudi forces would be deployed.[70]

Sheikh Tawakkol Salem Yassin, a leader of the General Council, generally echoed the position of the sit-in committee, saying the group “looks forward to Saudi Arabia implementing the oil pipeline project through al-Mahra, but it must be done in accordance with international agreements, benefitting the people of the governorate.”[71]

UAE Seeks Influence in Al-Mahra and Socotra Through STC

The UAE made inroads into Al-Mahra early in the war, from 2015 to 2017, through a combination of building up local security forces and providing humanitarian aid through the UAE Red Crescent. After helping train at least 1,800 Mahri forces,[72] the UAE grew frustrated when the governor at the time, Bin Kuddah, insisted they take orders from the local authority rather than Emirati officers.[73] Abu Dhabi seemingly abandoned its fledgling influence campaign in early 2017, only to take an indirect approach later that year after the formation of the STC in Aden. The separatist group’s president, Aiderous al-Zubaidi, offered Ben Afrar a seat on the STC representing both Al-Mahra and Socotra. Ben Afrar accepted the position, before promptly losing it by stating in his inauguration speech that the STC arm in Al-Mahra would operate under the authority of the Hadi government in direct contradiction to the council’s oft-cited secessionist goals.[74]

The UAE withdrew many of its remaining forces from Al-Mahra in September 2018.[75] After its broader troop drawdown in 2019, financial responsibility for the forces it trained apparently shifted to Saudi Arabia. The January-February 2020 payment document described above (Figure 1) includes a line item for “the forces transferred from the Emirati side,” noting payments required for 1,890 individuals.

The STC’s takeover of Socotra in June appears to have helped Ben Afrar reconsider joining its ranks, given that his armed brigade joined the island’s secessionist rulers immediately after the takeover, and Ben Afrar publicly defended STC demonstrators in Al-Ghaydah the following month. The UAE’s influence in Yemen is perhaps most apparent in Socotra, where the UAE Red Crescent carries out a slew of development projects, including expanding the Hawlaf sea port and constructing housing, schools and health facilities.[76] Emirati planes and cargo ships enter and exit Socotra without informing the Yemeni government.[77]

Qatar, Accused of Meddling, Criticizes Riyadh’s Role

Qatari media have publicized Riyadh’s interventions in Al-Mahra and highlighted the Saudi opposition,[78] but the extent of Doha’s involvement in the Gulf power struggle in Al-Mahra is unclear. Even so, Mahris have paid the price for Saudi suspicions of Qatari meddling in the governorate. Saudi forces have detained residents of the governorate on accusations of working with Qatar or with Hezbollah and other anti-Saudi groups.[79] Human Rights Watch documented 16 arbitrary detentions by Saudi and allied Yemeni forces, alleging torture and illegal transfers of detainees to the kingdom, between June 2019 and February 2020.[80] One of the detainees, a journalist, said that interrogators told him that if he didn’t sign a confession about his supposed links with Iran-backed Hezbollah and the Houthis, Qatar and the Omani intelligence services, they would behead his younger brother, who was also detained.[81]

In response to the STC takeover of Aden in August 2019, Al-Hurayzi formed a National Salvation Council in coordination with Fadi Baoum, a southern separatist and anti-coalition figure sponsored by Doha.[82] Qatar’s interests have aligned to an extent with Tehran and Muscat since Riyadh and Abu Dhabi led a Gulf Arab push in 2017 to isolate Qatar within the region.[83]

Conclusion

Al-Mahra’s historically consensus-based ruling style has been put to the test since the intervention of Saudi forces in the governorate starting in late 2017. Tension came to a head in February 2020, when several Yemeni soldiers guarding a Saudi convoy carrying out routine inspections at an important border crossing were ambushed by tribesmen. It marked the end of pro-Saudi Governor Bakrit’s time in office. In his place, Yasser, a seasoned Mahri politician with a good reputation in the governorate, was appointed to prevent competing power brokers from spinning out of control.

After more than six months on the job, Yasser has proven reasonably capable of bringing together Al-Mahra’s influential figures to address differences, and has calmed armed clashes that had been intensifying since Saudi forces began exerting more control in the governorate. He has had to contend with shifting alliances as Riyadh reached out financially and through proposals for development projects to secure the loyalty of Mahri tribesmen. However, local political dynamics have started to change markedly once again, since the UAE-backed STC’s power grab on the Socotra archipelago, which is in many ways considered an extension of Al-Mahra.

The change of power on the island marks a win for the Emiratis, who abandoned attempts to exert influence in Al-Mahra in 2017 after locals rejected Abu Dhabi’s attempts to run the paramilitary force it built there. Building on the Socotra takeover and broader momentum throughout the south after declaring self-rule in April, STC attempts to hold demonstrations in Al-Mahra’s capital in July met a backlash by Yasser’s security forces, tribes allied with Al-Hurayzi and the sit-in committee.

In perhaps no single Mahri politician is the pull of competing regional powers more visible than Ben Afrar, the longtime Oman ally whose anti-coalition position since 2017 has shifted dramatically in recent months. Ben Afrar had previously lived in Saudi Arabia and was installed as the head of the General Council of the People of al-Mahra and Socotra with the help of the kingdom in 2012.[84] He was instrumental in driving Emirati forces out of Al-Mahra in 2017 and helped form the anti-Saudi sit-in committee, but threw his support behind the STC presence in Socotra in 2020.[85] His newfound openness to the STC cost him significant local support, though he, like other political and tribal figures, can count on being courted by Riyadh and Muscat. The political situation in Al-Mahra remains fluid as loyalties realign following the STC takeover of Socotra and Gulf powers compete for local influence using the variety of tools at their disposal, including coercion and cooptation.

Casey Coombs is a freelance journalist and former managing editor of Almasdar Online English. His work focuses on Yemen, where he was based from 2012 to 2015. He tweets @Macoombs.

Annex A:

Translation of a schedule for disbursement of pay to various tribesmen, fighters and others in Al-Mahra from January 19, 2020-February 7, 2020.

Timesheet for Salary Disbursements

|

No |

Day |

Date |

Tribe or Military Unit |

Quantity |

|

1 |

Sunday |

19/1/2020 |

Kuddah tribe + Balhaf tribe + Kathiri tribe + Zuwaidi tribe |

650 |

|

2 |

Monday |

20/1/2020 |

Reinforcement battalion and camp security + Kalashat tribe |

620 |

|

3 |

Tuesday |

21/1/2020 |

Governor’s Force |

1089 |

|

4 5 |

Wednesday Thursday |

22/1/2020 23/1/2020 |

The forces transferred from the Emirati side |

1890 |

|

6 |

Friday |

24/1/2020 |

Sultan force + Saudi special task forces + Coalition Rapid Response force |

793 |

|

7 8 |

Saturday Sunday |

25/1/2020 26/1/2020 |

Al-Ghaydah security + Al-Masilah security + Hat security + Huswain security + Hawf security + Sayhut security + Qishn security + Wasik security + Traffic police + Security Department officers + Shahin Port officers + Prisons Department + Police + Civil Registration + Tanhala center + Special Forces Command + SSF at the northern airport gate |

1181 |

|

9 |

Monday |

27/1/2020 |

Officers and soldiers of Al-Ghaydah axis + air force base command + air force police |

738 |

|

10 |

Tuesday |

28/1/2020 |

Political Security + Political Security workers in the airport + National Security + judges and courts + military police |

923 |

|

11 |

Wednesday |

29/1/2020 |

Coast Guard + officers and soldiers of maritime radar + ports and Customs + Austal and fiber boat crews + media members + Al-Ghaydah airport employees + airplane logistics unit |

688 |

|

12 13 |

Thursday Friday |

30/1/2020 31/1/2020 |

Officers and members of Brigade (137) + Al-Ghaydah axis members |

1443 |

|

14 |

Saturday |

1/2/2020 |

Arrangements |

|

|

15 |

Sunday |

2/2/2020 |

Border guards + Zaabnout tribe |

766 |

|

16 17 |

Monday Tuesday |

3/2/2020 4/2/2020 |

Officers and members of Brigade (123) |

2492 |

|

18 |

Wednesday |

5/2/2020 |

Arrangements |

|

|

19 20 |

Thursday Friday |

6/2/2020 7/2/2020 |

Samoudah tribe + Manahil tribe + Al-Awamer tribe |

1500 |

|

Total |

14775 |

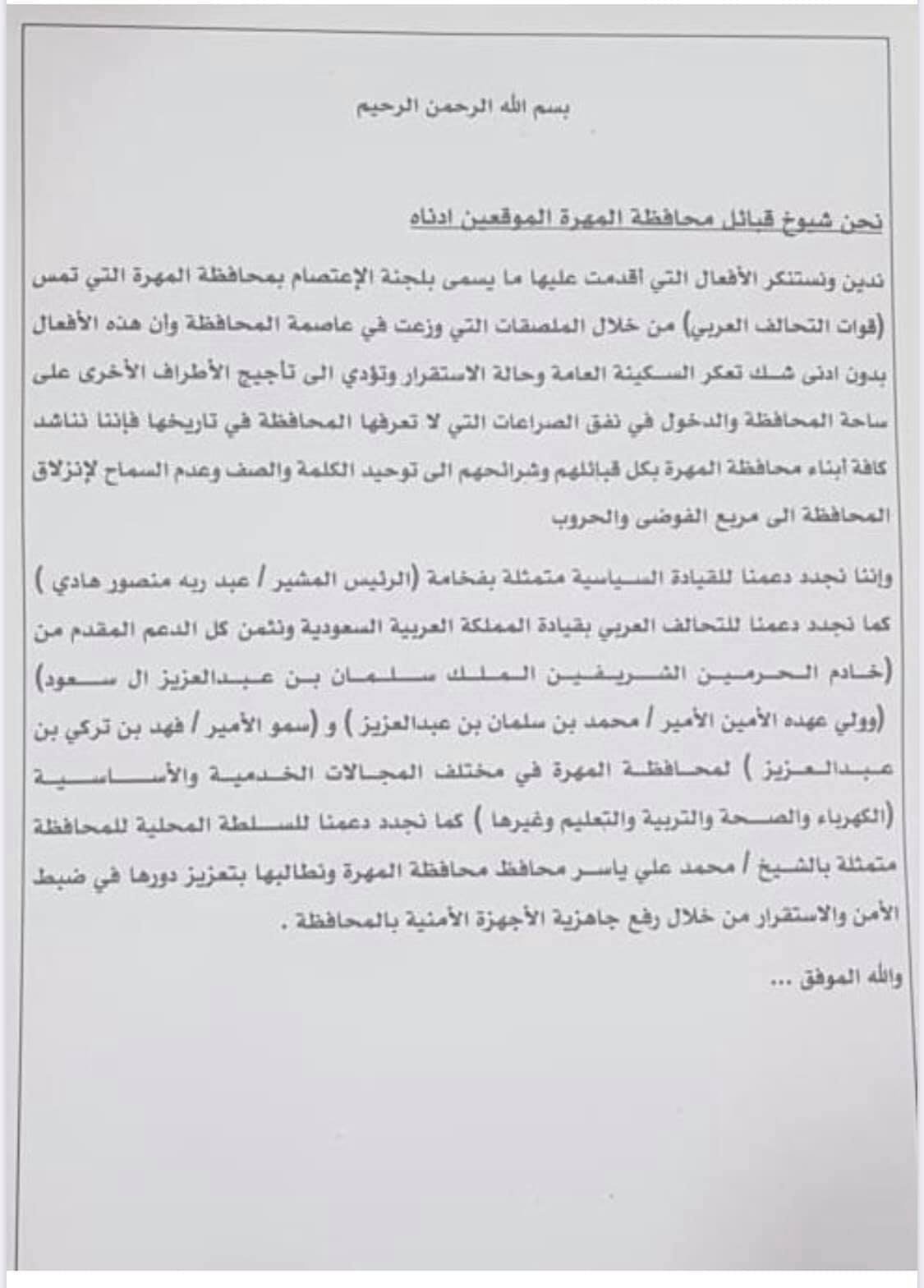

Annex B:

Copy of the letter signed by 63 Mahri tribal sheikhs affirming their support for President Hadi, Saudi leaders and the Saudi-led Arab coalition, followed by an English translation and translated list of signatories.

We are the sheikhs of the tribes of Al-Mahra governorate, undersigned

We condemn the actions taken by the so-called sit-in committee in Al-Mahra governorate, which targets (the Arab coalition forces) through posters distributed in the governorate’s capital.

These actions disturb the public tranquility and the state of stability and lead to inflaming other parties in the governorate’s arena and to dragging the governorate into a tunnel of conflicts that the governorate has not known in its history. We call on all the sons of Al-Mahra governorate, all the tribes and components, to unite their statements and rank and not allow the governorate to slip into the chaos and wars.

We renew our support for the political leadership represented by President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi and our support for the coalition led by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. We thank the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques King Salman bin Abdel Aziz al-Saud and his crown prince, Prince Mohammed bin Salman bin Abdel Aziz, and His Highness Prince Fahd bin Turki bin Abdel Aziz for their support for Al-Mahra governorate in all service and basic areas (electricity, healthcare, education and others). We renew our support for the local authority represented by Sheikh Muhammad Ali Yasser, the governor, and we call on it to strengthen its role in maintaining security and stability by raising the security readiness in the governorate.

(Signatures of 63 sheikhs were attached to the letter on separate pages, as follows.)

- Salem Saad al-Sharaf Kalashat

- Hamad Salem Hamad Salem Moghaddam al-Zuwaidi

- Ahmed Ali al-Zuwaidi

- Khaled Mabrouk Zaabnout

- Imron Mohammed Ali Aqeed

- Mubarak Ali Mubarak Bakrit

- Saleh Ali Ahmed al-Jadhi

- Mohammed Saad al-Jadhi

- Suleiman Ali Salim bin Omar

- Ali Mohammed Mesmar

- Ahmed Saeed Ahmed Afrar

- Saleh Mohammed Elyan

- Nasser Saleh Nasser al-Assad

- Ali Saleh Arba’een

- Ahmed Suhail Zaabnout

- Saleh Hafiz al-Sulaimi

- Saleh Mohammed Rajihit

- Saeed Ahmed al-Zuwaidi

- Mohammed Ali Raafit

- Mohammed Salem Kalashat

- Ahmed Mohammed al-Zuwaidi Kalashat

- Salem Eidah Kuddah

- Ayed Salim Kuddah

- Saad Ali Makhbal

- Tawakkol Salem Balhaf

- Mohammed Saad al-Sweifi Balhaf

- Uthman Ahmed al-Mahri

- Hussein Abu Bakr Ahmed

- Ahmed Salem ‘Ammor bin Hafeez

- Ibrahim Mohammed bin Zain

- Ahmed Ahmed Uthman Bakrit

- Awad Ali Yasser Raafit

- Saeed Ali al-Qumairi

- Salem Abdullah Moqaddam

- Abdullah Wahhas Balhaf

- Saleh bin Bakhit al-Kathiri

- Bakhit Salem Bakhit al-Kathiri

- Ahmed Salem Awad al-Huraizy

- Mulim Salem Zaabnout

- Khaled Mabrouk Zaabnout

- Mahfouz Harmash Mahomed

- Ali Bakhit al-Mahri

- Mafrej bin Habta Samoudah

- Saadotin Nasser Sa’atin

- Said Saleh Moghaifeeq

- Salim Saleh Yasehoul

- Al-Barak Saeed al-Kathiri

- Ahmed Mohammed Hool al-Kathiri

- Misbah Mohammed Shareb Qumsait

- Hariz Salem Qumsait

- Mohammed bin Arman Samoudah

- Manasir Mohammed al-Minhali

- Said Barak al-Ameri

- Muslih Yasser Yasehoul

- Saeed Mabkhout al-Awbathani

- Salim Nokhadhi al-Awbathani

- Mohammed bin Saad al-Rashidi

- Saad bin Kuddah

- Salah Abdullah al-Dehaimi

- Mohsen Mohammed Balhaf

- Ahmed Salem Arashi

- Suleiman Ali Suleiman al-Huraizi

- Salim Muslim Qumsait

This paper was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies with the Oxford Research Group, as part of Reshaping the Process: Yemen program.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Oxford Research Group (ORG) is an independent organization that has been influential for nearly four decades in pioneering new, more strategic approaches to security and peacebuilding. Founded in 1982, ORG has provided cutting-edge research and advocacy in the United Kingdom and abroad while managing innovative peacebuilding projects in several Middle Eastern countries.

Endnotes

- Ahmed Nagi, “Oman’s Boiling Yemeni Border,” Carnegie Middle East Center, March 22, 2019, https://carnegie-mec.org/2019/03/22/oman-s-boiling-yemeni-border-pub-78668

- “Profile of al-Mahra Governorate,” National Information Center, https://yemen-nic.info/gover/almahraa/brife/

- See Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606

- Shahin and Sarfait border crossings with Oman, Nishtun naval port and Al-Ghaydah Airport are under the management of Saudi forces.

- Conflict and protest events in Al-Mahra spiked following the arrival of Saudi forces to the governorate. See Emile Roy, “Yemen’s fractured south: Socotra and Mahrah,” ACLED, May 31, 2019, https://acleddata.com/2019/05/31/yemens-fractured-south-socotra-and-mahrah/; Prior to the February 2020 violence, there were armed clashes in al-Anfaq in November 2018 and near the Shahin border crossing in March 2019. In April 2019, Saudi helicopters fired on a police checkpoint in Al-Mahra, angering locals. See also Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606

- “Violent clashes between Saudi Yemeni forces and gunmen in Mahra [AR],” Anadolu Agency, February 17, 2020, t.ly/UrPQ

- “Arab coalition reveals the details of responding to an armed ambush that targeted its forces in Al-Mahra [AR],” Al-Omanna.net, February 18, 2020, https://alomanaa.net/details.php?id=108776

- “Socotra: The Sultan’s Ben Afrar Brigade announces joining the Transitional Council [AR],” Al-Mandab News, June 22, 2020, https://almandeb.news/?p=256338

- “Sheikh Muhammad bin Abdullah appointed head of the Sultan Afrar family council,” Socotra Post, July 10, 2020, https://socotrapost.com/localnews/4411

- “Republican decision to appoint Mohammed Ali Yasser as governor of Al-Mahra governorate [AR],” Saba Net, February 23, 2020, https://www.sabanew.net/viewstory/59351. In Yasser’s place, Hadi appointed Mohammed Abdullah bin Kuddah, a minister of state who served as Al-Mahra’s governor twice before (1990-91, 1992-94). Bin Kuddah’s dismissal in late 2017 also came under pressure from the Saudi-led coalition. Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606

- Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606

- Yasser is related to Ali Al-Hurayzi, a tribal leader and former senior government official, and Ahmed Balhaf, a spokesman of the peaceful sit-in committee of the people of Al-Mahra. Interview with an official close to Governor Yasser on August 11, 2020.

- “Vice chairman of Al-Mahra sit-in committee Sheikh Aboud Haboud Qumsit: the new governor is an acceptable figure, and our goal is a complete exit from Saudi occupation [AR],” Al-Mahra Post, February 23, 2020,

- “With broad welcome … the General Council of Al-Mahra and Socotra welcome the new governor [AR],” Al-Mahra Post, February 24, 2020, https://almahrahpost.com/news/15420#.XzTkEOyM6DY

- From the 16th century until the formation of the now-defunct South Yemen in 1967, the Afrar family led the Mahra Sultanate, composed of the current governorate of Al-Mahra and the Socotra archipelago. Despite the dissolution of the sultanate, the Afrar family has remained influential in local politics. Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606

- Al-Hurayzi was dismissed from his government post in June 2018, following a failed attempt by Saudi forces to arrest him for publicly criticizing and rallying opposition Riyadh’s plans to build an oil pipeline through Al-Mahra and accusing the Saudis of occupying the governorate.

- Al-Mahra Media Center, “Biography of the governor of Al-Mahra, Mohammed Ali Yasser [AR],” Facebook, February 26, 2020, https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=2747873681917137&id=1224050437632810

- “Biography of Sheikh Muhammad Ali Yasser [AR],” YouTube, May 28, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QT5LMcytIio&feature=youtu.be

- Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606

- “The Public Funds Prosecution Office for Corruption submits a memorandum to the Governor of the Central Bank and demands that he stop the violations of the Al-Mahra governor [AR],” Aden Al-Ghad, July 10, 2019, https://adengad.net/news/396315/

- According to documents seen by the source, the debts include payments to contractors who carried out projects in the governorate, private payments as well as cars for a number of officials in Al-Mahra. Confidential interview with a local official, August 2020.

- “Rajeh Saeed Bakrit appointed a member of the Shura Council [AR],” Saba Net, February 23, 2020, https://www.sabanew.net/viewstory/59352

- “Al-Mahra security committee calls on all political components to unite efforts to advance the governorate [AR],” Al-Mahra Post, June 25, 2020, https://almahrahpost.com/news/17715#.XzT2CojXLIU; “During his meeting with leaders of the transitional council in the governorate … Yasser confirms the unification of the efforts of the local authority and the political components to serve the governorate and its people [AR],” Aden Al-Ghad, April 29, 2020, https://adengd.net/news/461140/

- Interview with a Defense Ministry official, September 19, 2020.

- In November 2018, two people were killed in a firefight that erupted between tribal protesters and Saudi-backed forces. Bel Trew, “Inside east Yemen: the Gulf’s new proxy war no one is talking about,” The Independent, August 31, 2020,

- Interview with an official close to Governor Yasser, April 22, 2020. The governor attended a February meeting in Riyadh at which he said he would take this course of action.

- Al-Mahra Media Center, “Funeral for the special task force martyrs who were killed in the terrorist incident,” Facebook, March 1, 2020, https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=2756293724408466&id=1224050437632810

- Al-Mahra Media Center, “Local authority directs three million to be paid to each martyr and two million for the wounded [AR],” Facebook, February 26, 2020, https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=2747808998590272&id=1224050437632810

- Interview with a member of the investigative committee, September 12, 2020.

- The rift between the local authority under Bakrit and the sit-in committee is apparent in the groups’ starkly different interpretations of the February 17 clashes between the Saudi convoy and Mahri tribes near the Omani border: “Conflicting narratives emerge over clashes between Saudi military, tribal gunmen on Yemen-Oman border,” Al-Masdar Online English, February 21, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/375

- Bakrit established a Special Task Force and expanded the military police, Personal Protection Forces and a security unit to guard sensitive sites, each of which has between 200 and 250 members. The governor also authorized the coalition to arm a counter-terrorism battalion with armored vehicles. See Issa bin Nahl al-Qumairi, “Two years of achievements in the security and military establishment [AR],” Facebook, January 22, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/100003019577118/posts/2497877566989538/?extid=45fSEVBPHnIj7Qih&d=n

- Al-Mahra Media Center, “Governor of Al-Mahra meets with sit-in committee and calls for cooperation,” Facebook, March 8, 2020, https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=2770957242942114&id=1224050437632810

- Interview with officials close to Governor Yasser on August 12, 2020.

- Interview with a Nishtun port official, September 2020; “Saudi forces expel a Yemeni battalion from the Nishtun port in Mahra,” Al-Jazeera, April 17, 2020, ibit.ly/a1Pa

- Interview with Ali Mubarak Mahamed, Deputy of the Media Committee of the Al-Mahrah Sit-in Committee, August 10.

- “Transgressions and interventions of the coalition representative in the course of Shahin customs work,” Letter to Governor Yasser, June 13, 2020; “Threatening the deputy general manager of Shahin customs by the coalition’s representative,” Letter to Governor Yasser, June 14, 2020.

- “In his first comments after his departure … Governor of Socotra: Saudi forces left transitional forces to control the island [AR],” Al-Masdar Online, June 23, 2020, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/196394

- “After consultative meetings … the preparatory committee for the meeting of Al-Mahra is taking its first steps amid reservations of some [AR],” Al-Mahra Net, July 23, 2020, https://almahriah.net/local/3126

- “Bin Kuddah: The STC and the Socialist Party apologized for participating in the preparatory committee for the expanded meeting in Al-Mahra,” Al-Mahra Satellite Channel, July 14, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yfc9Mooxp6w

- “Yemeni government: STC declaration “a total coup” against state institutions,” Al-Masdar Online English, April 26, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/700

- Ahmed Balhaf, “Our leaders in the peaceful sit-in committee are communicating with sheikhs, notables and dignitaries in the southern governorates,” Facebook, May 12, 2020, https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=696710430870313&id=431441427397216

- “A meeting between Ben Afrar and the Deputy Minister of Defense of Saudi Arabia. Does it end the tension in Al-Mahrah?” Al-Masdar Online, September 1, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/article/a-meeting-between-sheikh-and-bin-afarar-and-the-deputy-minister-of-defense-of-saudi-arabia-does-it-end-the-tension-in-al-mahrah

- “Socotra: The Sultan’s Ben Afrar Brigade announces joining the Transitional Council,” Al-Mandab News, June 22, 2020, https://almandeb.news/?p=256338

- “Sheikh Al-Huraizi: Ben Afrar broke out of consensus and stood with Saudi Arabia and the Emirates,” Al-Mahra Satellite Channel, July 5, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u8AT6lR7cZ4; “Al-Huraizi warns the General Council for the Sons of Al-Mahra and Socotra against being led by the Saudi-Emirati occupation,” Al-Mahra Khabour, July 7, 2020, https://almahrahkhboor.net/news/7954

- “Sheikh Muhammad bin Abdullah appointed head of the Sultan Al-Afrar family council,” Socotra Post, July 10, 2020, https://socotrapost.com/localnews/4411

- “Activists: Ben Afrar is a “traitor” and Al-Mahra is Yemeni and against the occupation,” Huna Aden, July 12, 2020, https://hunaaden.com/news59316.html

- “On the eve of the transitional event … tribal militants take control of the stage for celebrations in Mahra,” Al-Masdar Online, July 24, 2020, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/198815

- “Security committee in Al-Mahra decides to prevent any public activity ‘for any party,’” Al-Masdar Online, July 25, 2020, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/198879/amp

- General Council of the Sons of Al-Mahra and Socotra, “General Secretariat of the General Council holds an extraordinary meeting,” Facebook, July 27, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=3458953434166083&id=711393892255398

- Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606

- Interview with a local official, September 14, 2020; Peter Salisbury, “Yemen: National Chaos, Local Order,” Chatham House, December 2017, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2017-12-20-yemen-national-chaos-local-order-salisbury2.pdf ; “More than 7 billion riyals, customs revenue, in Mahra last year,” Yemen Voice, February 6, 2013, https://yemenvoice.net/print.php?id=50564

- Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606

- Mareb Alward, “Analysis: Oman’s role in Yemen: Balancing international neutrality and local interests,” Al-Masdar Online English, December 19, 2019, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/198

- Interview with Gulf analyst Elana DeLozier on September 24, 2020.

- “Saudi Arabia prevents dozens of materials from entering Yemen through a shipping port in Al-Mahra (documents),” Al-Mahra Post, March 11, 2020, https://almahrahpost.com/news/15584#.X28fMGgzZPY

- Interview with a Yemeni official at Nishtun port, September 2020.

- Interview with a senior Mahri official, September 2020.

- Ahmed Nagi, “Oman’s Boiling Yemeni Border,” Italian Institute for International Political Studies, March 22, 2019, https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/omans-boiling-yemeni-border-22588

- “We are the sheikhs of the tribes of Al-Mahra Governorate,” letter signed and stamped by 63 tribal sheikhs, circulated July 2020.

- Document signed by Hakeem Al-Matari, head of the joint operation room of coalition and Yemeni forces in Al-Mahra. English version in Annex A translated from original Arabic by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies.

- “SDRPY projects factsheet (April 2020),” SDRPY, http://www.arabia-saudita.it/files/news/2020/06/sdrpy_projects_factsheet_april_2020_29_april.pdf

- Braden Fuller, Emile Roy, “Exporting (in)stability: the UAE’s role in Yemen and the Horn of Africa,” ACLED, October 10, 2018, https://acleddata.com/acleddatanew/2018/10/10/exporting-instability-the-uaes-role-in-yemen-and-the-horn-of-africa/

- Ibid.

- Interview with Sheikh Tawakkol Salem Yassin, president of the executive board of the General Council of the Sons of Al-Mahra and Socotra on August 16, 2020.

- “Letter dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council,” Security Council, January 27, 2020, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3850088?ln=en

- Interview with Sheikh Tawakkol Salem Yassin, president of the executive board of the General Council of the Sons of Al-Mahra and Socotra on August 16, 2020.

- Interview with Ali Mubarak Mohammed, Deputy of the Media Committee of the Al-Mahrah Sit-in Committee on August 10.

- “Sheikh Ali Salem al-Hurayzi: Saudi Arabia came to occupy Yemen,” Al-Mahrah Tube, October 18, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zgwwwrMdoe0&t=40s. Al-Hurayzi said he discussed the prospects of a Saudi pipeline with former President Ali Abdullah Saleh in the 1990s.

- Interview with Ali Mubarak Mahamed, deputy of the media committee of the Al-Mahrah Sit-in Committee on August 10.

- Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606

- Interview with Sheikh Tawakkol Salem Yassin, president of the executive board of the General Council of the sons of Al-Mahra and Socotra on August 16, 2020.

- Interview with a Mahri military official in September 2020; Ahmed Nagi, “A Shadow Conflict Worth Watching,” 2020, https://carnegie-mec.org/2020/02/20/mahra-yemen-shadow-conflict-worth-watching-pub-80986. Sources told Nagi that the UAE had trained about 2,500 Mahri forces.

- Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606

- Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606

- “The UAE withdraws its forces from Mahra, following a dispute with Saudi Arabia over influence [AR],” Al-Mawqea Post, September 22, 2018, https://almawqeapost.net/news/34192

- “UAE aid for Socotra education and health services,” Emirates News Agency, June 30, 2020, https://wam.ae/en/details/1395302852082

- “Socotra: UAE releases Socotri-Emirati citizens detained at airport by Yemeni authorities,” Al-Masdar Online English, December 15, 2019, https://al-masdaronline.net/local/185; “Socotra Port Director: The illegal entry of an Emirati ship into Socotra Port [AR],” Socotra Post, September 20, 2020, https://socotrapost.com/socotranews/6240; “Governor of Socotra sends letter to President Hadi about dangerous developments on the island [AR],” Alyom Press, September 28, 2020, http://www.alyompress.com/news.php?id=24486

- See, for example, “Al-Mahra, Hidden Saudi Intentions [AR],” Al Jazeera Investigations, January 19, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.net/programs/private-investigation/2020/1/19/; “The former deputy governor of Al-Mahra accuses Saudi Arabia and the UAE of escalation in the province [AR],” Al Jazeera, July 26, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.net/news/politics/2020/7/26/; and Mohammed Abdul Malik, “Why does Saudi Arabia insist on seizing Al-Mahra’s ports? [AR],” Al Jazeera, February 18, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.net/news/politics/2020/2/18/

- “(Exclusive) Saudi Forces Arrest Dozens of Yemenis from the Shahen Port and Deport Them to Riyadh,” Al-Mahra Post, December 8, 2019, https://almahrahpost.com/news/14396#.X24pF2hKhPZ

- Human Rights Watch. “Yemen: Saudi Forces Torture, ‘Disappear’ Yemenis.” March 25, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/25/yemen-saudi-forces-torture-disappear-yemenis#

- Ibid.

- “After opposition meetings with Russian, British and Saudi diplomats, where is Al-Mahra headed?,” Al-Masdar Online, September 5, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/171333; “War’s Elusive End – The Yemen Annual Review 2019,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, January 30, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/8923

- Salem Humaid, “Is Oman another proxy for Iran and Qatar?” The Arab Weekly, September 28, 2019, https://thearabweekly.com/oman-another-proxy-iran-and-qatar; Abdullah Baabood, “The Middle East’s New Battle Lines: Qatar, Kuwait, and Oman,” European Council on Foreign Relations, accessed September 29, 2020, https://www.ecfr.eu/mena/battle_lines/oman

- Yahya al-Sewari, “Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 5, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7606

- “Socotra: The Sultan’s Ben Afrar Brigade announces joining the Transitional Council [AR],” Al-Mandab News, June 22, 2020, https://almandeb.news/?p=256338

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية