Executive Summary

The United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen recently accused the internationally recognized Yemeni government, its central bank and commercial food importers in the country of colluding to embezzle nearly half a billion dollars. The accusations were included in the panel’s annual report to the UN Security Council, published on January 25, which detailed a wide spectrum of findings related to political, military, security and economic developments in Yemen in 2020.

In the report’s economic section, the Panel of Experts concluded that the two primary Yemeni belligerents in the country’s ongoing conflict – the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the armed Houthi movement – had both illicitly diverted the country’s economic and financial resources to serve their own ends, thereby deepening the plight of millions of Yemeni citizens who currently face one of the largest humanitarian crises in the world. This Sana’a Center report will focus on the accusations against the Aden-based central bank (CBY-Aden) affiliated with the Yemeni government, which the panel said has engaged in “money-laundering and corruption practices.”[1]

Specifically, the panel accused the central bank of facilitating the embezzlement of US$423 million from a US$2 billion deposit Saudi Arabia made to the CBY-Aden in early 2018 for the purpose of financing basic commodity imports and stabilizing the Yemeni rial (YR) exchange rate. The Panel of Experts report asserts that from July 2018 to early August 2020, the CBY-Aden facilitated funds being syphoned off of the Saudi deposit through a financial mechanism that offered commercial traders a better-than-market exchange rate on letters of credit (LCs) to finance purchasing and importing goods from abroad. Of these traders, the Panel of Experts said the Hayel Saeed Anam (HSA) Group, Yemen’s largest business conglomerate, received US$194.2 million in misbegotten funds, almost half of the total amount the panel says was embezzled.

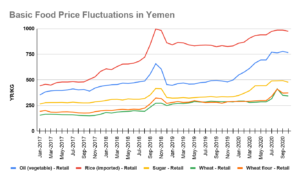

The panel’s report, however, contains serious errors in its evidence and arguments. Among the panel’s assertions is that Yemenis did not benefit from the LC system through lower market prices for the basic imports it covered, namely rice, wheat, sugar, milk and cooking oil. This claim would appear demonstrably incorrect – while Yemenis have suffered from currency depreciation and price inflation throughout most of the conflict, they received a relative reprieve from the end of 2018 to the end of 2019, when the average price of a minimum food basket decreased slightly year-on-year and the Yemeni rial exchange rate was generally stable. This corresponded directly with the period in which the largest share of the Saudi deposit was disbursed through import financing. The panel also erred in the basic data and calculations it used for determining the differential between the exchange rate the CBY-Aden offered on LCs and the average market exchange rate at that time. The panel’s determination that the central bank and its governor had violated Yemeni law was then based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the CBY’s legal mandate, which is to achieve and maintain domestic price stability, and not, as the panel put it, to seek the “largest possible return” in managing its foreign currency holdings. Given the false premises upon which the Panel of Experts built its argument, its specific conclusions are unsound.

The general concerns the panel’s report raises, however, warrant serious consideration. Since the central bank administration was transferred from Sana’a to Aden, in 2016, there has been general ambiguity and opacity regarding its operations, in large part due to a woeful lack of oversight, crippled governance structures and political infighting. There has been no audit of the central bank since its move to Aden and it has even stopped publishing its annual financial statements. Regarding the LC mechanism specifically, the bank has had no meaningful control and compliance measures overseeing how each batch of import financing is issued, and no monitoring and accountability framework to ensure it is achieving its goal of price stability. There have also been numerous accusations of corruption at the CBY-Aden arising from the private sector, in Yemeni media, and between prominent figures at the CBY-Aden itself. While a rigorous and impartial investigation is needed to determine if public funds have been misused, there has clearly been ample opportunity for corruption.

Regardless of the validity of the specific accusations put forward in the Panel of Experts report, it has shone a spotlight on what is undeniably a dysfunctional and deeply problematic state of affairs at the CBY-Aden, and the consequences of doing so could be dire. The CBY-Aden has essentially run out of foreign currency with which to finance imports and support the value of the Yemeni rial. Consequently, the rial hit a new all-time low in value as 2021 began and has since continued to depreciate. The weakening currency is driving up commodity prices and diminishing consumer purchasing power – meaning the affordability of life’s basic necessities is being pushed further beyond the reach of millions of Yemenis who are already dependent on aid to survive. The only near-term counter to this trend is for large-scale new foreign currency reserves to be made available to finance Yemen’s imports, but this does not appear to be forthcoming. Saudi Arabia, already reluctant to renew its financial support for the CBY, will be more so after the panel’s accusations. Other potential donors may likewise be deterred.

There is a crisis of confidence regarding the Yemeni government’s central bank. Yemenis and the international stakeholders who would support the country need to see dramatic and immediate action taken to begin restoring faith that this crucial institution can and will carry out the country’s monetary and fiscal policies in a principled, transparent and accountable fashion. To this end, this report makes the following recommendations:

The internationally recognized Yemeni government should immediately:

- Dismiss the CBY-Aden’s entire senior leadership and board of directors and undertake a process to fill their positions with highly qualified, politically unaffiliated technocrats with a demonstrable record of upholding the public interest.

- Order comprehensive, independent audits of all central bank operations. Upon completion, the full results of the audits should be made public.

- Appoint an independent investigative committee to examine all transactions related to the Saudi deposit and the central bank’s sales and purchases of foreign currencies.

- Launch criminal investigations and prosecutions against any individuals suspected of violating Yemeni laws, and the central bank law in particular, in any aspect of their work or dealings with the CBY-Aden. Specifically, each of the four individuals who have held the post of governor at the CBY-Aden since its relocation from Sana’a in 2016, all members of their respective administrations, and all members of the board of directors should be investigated for possible criminal wrongdoing.

- Begin exploring plausible policy options to foster competition and limit the oligopolistic and monopolistic tendencies of the Yemeni market.

As soon as possible under the new senior leadership and board of directors, the CBY-Aden should:

- Immediately publish all data detailing the share of the Saudi deposit each Yemeni importer received.

- Initiate comprehensive governance measures to reform the CBY-Aden’s institutional and organizational structures, develop its monetary policy frameworks and strengthen accountability and transparency mechanisms. This must include an overhaul of the central bank’s import financing system to include accountability and transparency mechanisms that meet international standards.

- Adopt a unified, free-floating managed exchange rate policy and scrap the current use of multiple exchange rates for internal accounting and intragovernmental financial transactions. The new exchange rate policy should take into consideration the bank’s currently weak foreign currency stocks and attempt to influence the supply and demand sides of the foreign exchange market indirectly through systematically planned and well-studied interventions.

- Begin the necessary procedures to publish its financial statements and disclosures linked to them since the central bank was relocated to Aden in 2016.

- Resume publishing of its monthly monetary and banking developments bulletin and annual report. The CBY-Aden should adopt clear transparency measures to publish, on a regular basis, all data and information relating to its exchange rate and monetary activities, decisions related to the financing of LCs and the importers benefiting from them, as well as financial sector market data and activities.

The HSA Group is the country’s largest conglomerate. With a longer history than that of the republic itself, HSA Group is a standard-bearer for Yemen’s commercial and private sectors generally and thus the restoration of its reputation is in the national interest. Given this, HSA Group should:

- Release all data regarding its use of the LC mechanism, specifically detailing HSA’s pricing data for commodities, and products that used commodities imported via LCs, sold in Houthi-controlled areas and in Yemeni government-controlled areas, to allow for transparency regarding HSA’s potential benefit from the market exchange rate and the rate received under various LCs.

- Commission an independent audit of all HSA Group’s activities related to its companies’ use of the CBY-Aden’s import financing mechanism and from any other source of foreign exchange intersecting with it.

- Release and publicize the full findings of this audit once it is complete as a demonstration of the group’s commitment to transparency and accountability.

The UN Panel of Experts on Yemen should immediately:

- Initiate a review of their 2020 annual report to correct errors and issue a public correction.

- Review the methodology by which the panel arrived at its erroneous figures and conclusions and make the necessary adjustments to avoid such errors in future reports.

-

Seek out and retain Yemeni expertise to assist with compiling and assessing information and data for its reports. The Panel of Experts is entirely non-Yemeni and clearly lacks an informed, and sometimes even basic, awareness of the local context.

Contents

- Import Financing Market Prior to the Conflict

- Import Financing Early in the Conflict and the Seeds of Currency Diversion

- The Saudi Deposit and the Establishment of the LC Mechanism

- The Preferential Exchange Rate for LCs

- The Responsiveness of Commodity Prices to Exchange Rate Fluctuations

Embezzlement Accusations Against the CBY-Aden

- The Panel of Experts’ Case

-

Failures in the Panel of Experts’ Evidence and Arguments

- Analysis Errors Misrepresent the Benefits to Yemenis from the CBY-Aden’s Import Financing Mechanism

- Data and Tabulation Errors Mar Calculation of the Exchange Rate Differential Between the Market and the LC Mechanism

- Misunderstanding the CBY-Aden’s Legal Mandate

- Specific Conclusions Deeply Flawed; General Concerns Still Warrant Consideration

Salient Concerns Regarding the CBY-Aden

- Questions of Elite Capture

- Lack of Oversight, Crippled Governance and Political Infighting at the CBY-Aden

Looking Ahead: Implications of the Panel of Experts Report

Background

Import Financing Market Prior to the Conflict

For decades, Yemen has been heavily dependent on foreign trade to supply domestic needs, importing up to 90 percent of its food necessities, including 100 percent of the rice consumed in the country.[2] In 2013, total imports were valued at US$10.8 billion, amounting to 32 percent of gross domestic product,[3] while the foreign exchange reserves at the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) closed the year at US$5.3 billion.[4] Oil and gas exports provided the largest source of foreign currency to help restock reserves at the CBY. This enabled the bank to achieve and maintain a reasonable degree of commodity price stability, which is the central bank’s primary legal mandate, according to Law No. 14 of 2000.[5] In 2014, oil and gas export revenues amounted to almost US$6.4 billion, or 36 percent of foreign currency inflows, while remittances were estimated at US$3.3 billion, or 18 percent of Yemen’s hard currency sources.[6]

Traders of basic commodities enjoyed unrestricted and continuous access to open lines of credit for foreign currency to import goods via a well-functioning letter of credit (LC) system, aided by a banking sector that could facilitate international trade through accounts held at overseas correspondent banks. The CBY’s import financing regime and judicious regulation of the exchange market prior to the current conflict allowed it to maintain an effective currency peg of 215 Yemeni rials (YR) per US$1 and shield food prices from dramatic fluctuations.

Import Financing Early in the Conflict and the Seeds of Currency Diversion

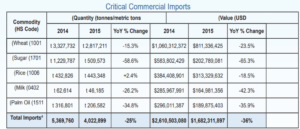

The escalation of the Yemen conflict in March 2015 led to rapid widespread economic collapse, disrupting established food supply chains (reflected in decreased imports, as shown in Figure 1 below) and leading to the near-total suspension of oil and gas exports, the country’s leading source of foreign currency inflows. Demand for fuel and basic commodity imports continued, however, rapidly depleting the CBY’s foreign currency reserves. These stood at US$4.6 billion in late 2014; during the first half of 2015 alone the central bank spent almost 40 percent of its reserves financing the import of basic commodities, including wheat grain, wheat flour, rice, sugar and oil derivatives.[7] Faced with rapidly declining reserves, in July 2015 the CBY began limiting its lines of credit for fuel imports, though by year’s end it had still expended nearly US$1.9 billion to cover fuel imports and basic commodities, at the official exchange rate of YR215/US$1, compared to around US$3.1 billion in 2014.[8]

Figure 1

Source: UN Comtrade/World Bank Group

The CBY’s ability to regulate the exchange market weakened as the conflict persisted, and a parallel market exchange rate began to emerge in early 2016. By February, the rial was trading at roughly YR250/US$1.[9] Currency arbitrage from import financing concurrently arose. During the first quarter of 2016, the CBY financed US$414 million in basic commodity imports using the exchange rate of YR215/US$1, with nearly 70 percent of this amount going to wheat, 20 percent to rice, and almost all the rest underwriting petroleum imports.[10] By June of the same year, the rial was trading in the market at close to YR300/US$1. According to sources aware of senior-level central bank discussions at the time, the CBY administration realized in early 2016 that the preferential exchange rate was not being reflected in the market prices of food commodities the bank was subsidizing, leading the CBY to adopt a contingency plan to lessen pressure on its shrinking foreign currency reserves. This saw the CBY end financing for sugar imports by February, and in the second quarter of 2016 the bank lowered the official exchange rate to YR250/US$1.

By September, food prices had surged 20.1 percent relative to pre-conflict;[11] the rial was trading on the market at over YR300 against the dollar and the CBY held just US$700 million in its foreign currency reserves.[12] The same month, the internationally recognized Yemeni government officially relocated the CBY headquarters from Sana’a to its interim capital, Aden.[13]

The transfer of the CBY headquarters created two competing central banks: CBY-Aden, affiliated with the Yemeni government, and CBY-Sana’a, affiliated with the armed Houthi movement. The former has international recognition and associated privileges, while the latter maintains purview over the country’s financial hub and Yemen’s largest population centers and consumer markets. Since the schism, the two CBYs have increasingly issued contradictory and incompatible mandates to Yemeni businesses and financial institutions, in an escalating struggle for control over the country’s monetary and fiscal policies, including the LC system for financing imports.

Following the central bank’s fracture, the commodity supply chain was heavily disrupted owing to a combination of factors. Chief among these was that importers were completely cut off from foreign currency and LCs from the CBY. They and the commercial banking sector also simultaneously faced increasing access restrictions to correspondent banking and the international financial system due to Yemen being elevated, in September 2016, to the highest global risk classification for anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing enforcement.[14] On November 9, 2016, the Yemeni government had the CBY-Sana’a’s connection to the SWIFT global financial network severed, thereby suspending financial transactions and money transfers through the network. It was not until mid-April 2017 that the CBY-Aden, and the country as a whole, was reconnected to the SWIFT network.[15] The connection remained inactive, however, due to the CBY-Aden lacking the capacity and technical knowledge necessary to operate the system, as well as a shortage of foreign currency reserves that could be sent through the SWIFT network. The informal exchange market increasingly operated according to its own dynamics, which, in conjunction with the CBY-Aden’s foreign currency shortage and the new rials printed by the Yemeni government to cover its widening budget deficit, increased downward pressures on the rial.

The Saudi Deposit and the Establishment of the LC Mechanism

In March 2018, the CBY-Aden received a US$2 billion deposit from Saudi Arabia. Intended to support imports of five basic commodities – rice, wheat, sugar, milk and cooking oil – rollout of the import financing was slated to begin in June (for more on this, see the April and May 2018 ‘Yemen at the UN’ reviews). By providing importers with foreign currency, the Saudi deposit was intended to relieve downward pressure on the rial’s value and stabilize market prices. By March 2018, the Yemeni rial was trading at an average rate of YR483/US$1, meaning it was worth less than half of what it had been when the conflict began. The currency’s depreciation created inflationary pressures across the Yemeni economy and was seen as the largest factor driving widespread increases in food insecurity and deepening the country’s humanitarian crisis. Significant downward pressure on the Yemeni rial came from traders purchasing foreign currency in the domestic exchange market to fund imports. According to a 2018 survey of leading Yemeni bankers, fuel traders’ unregulated demand for foreign currency to finance imports was viewed as the single largest pressure on the value of the rial.

In a circular to commercial banks on June 21, the CBY-Aden detailed an LC implementation framework, including 15 conditions that banks and traders were required to meet to be eligible to access foreign exchange funds from the Saudi deposit (for more, see ‘Yemen at the UN – June 2018 Review’). The most noticeable facet of the CBY-Aden LC mechanism was its cash-based approach: the CBY-Aden stipulated that only physical cash, in domestic currency bills, would be accepted as payment to access foreign currency funds. This meant that for food importers to qualify for import financing from the CBY-Aden, Yemeni banks acting on their behalf had to deposit half the cash liquidity equivalent of the foreign exchange funds requested at the central bank. Following this, the CBY-Aden would send a request to Saudi authorities for review before foreign currency funds were electronically wired from a CBY account in Jeddah to the importer’s correspondent account abroad. After obtaining Saudi approval, the LC mechanism required Yemeni banks to deposit the second half of the cash equivalent at CBY-Aden. Other payment instruments, such as checks and wire transfers, were not accepted under the LC system.

On November 13, 2018, the Aden-based Chamber of Commerce and Industry (CCI) sent a letter to Yemeni Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed outlining a list of issues it said were limiting importers’ engagement with the LC financing mechanism.[16] A primary complaint was that the LC mechanism did not include a cash clearing payment system for commercial banks and exchange companies in Houthi-controlled areas – where the country’s largest markets and population centers are located – to meet the LC mechanism’s cash requirements. Depositing banknotes directly at the CBY-Aden was arduous for these financial institutions, given Houthi restrictions. In its letter, the CCI suggested a solution: in lieu of these direct deposits, banks and exchange companies in Houthi-controlled areas could instead cover the Yemeni government’s expenditures on public salaries in northern areas as well as transfers made by international NGOs (INGOs) to Houthi-held areas from funds deposited at the CBY-Aden.

Another complaint was the requirement that the CBY-Aden receive full payment for the LC once the Saudi authorities had approved it; normally, full payment would be made upon the goods arriving at Yemeni ports. This weakened commercial traders’ ability to import and sell goods on credit. It also tied up importers’ liquidity and restricted trade, given that the LC approval could take months and there was no clear mechanism for complaints against breaches of deadlines. The LC mechanism required importers to bring all goods approved for financing in one shipment; it did not include provisions to permit delivery in multiple shipments in particular circumstances, for instance in times of maritime shipping difficulties or goods being scarce on the international markets. The CCI also complained that there was no monitoring mechanism that included private sector or community-based bodies to supervise the LC processes, in the interest of greater transparency and accountability. There is, it should be noted, no legal precedent for such oversight of CBY operations.

The following year, on April 20, 2019, the CBY-Aden and representatives of basic commodities importers reached an agreement on a new mechanism for LC financing to address some of the obstacles Yemeni importers had identified. However, while the agreement received the assent of the Yemeni prime minister, it was never implemented, according to a senior banking official aware of the proceedings.[17]

The CBY-Aden’s rollout of the import support mechanism in June 2018 was generally regarded in the market as having taken an excessively long time, with the resulting process being time consuming, cumbersome and inflexible. Following the rollout announcement in June 2018, the Houthi authorities also began to take increasingly coercive measures to dissuade Yemeni businesses and financial institutions from abiding by the CBY-Aden LC requirements. The result was that in the first four months of the LC mechanism’s operation only two batches of import financing were issued, amounting to just US$32.6 million.[18] For comparison, Yemen’s pre-conflict average monthly import bill for basic commodities had been estimated at US$217.5 million, according to 2014 figures from the World Bank.[19] In 2018 and 2019, the IMF estimated Yemen’s average monthly bill for basic food imports at US$178 and US$271 million, respectively.[20]

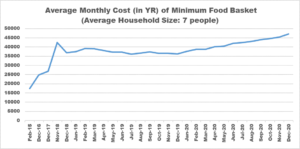

During the same period, from July to October 2018, the Yemeni rial experienced its most precipitous decline in value yet, depreciating 42 percent from the beginning of August to the end of October. At one point, the currency was worth less than YR800/US$1.[21] In concert, between June and October, the national average monthly per capita cost of the minimum food basket increased by around 28 percent.[22]

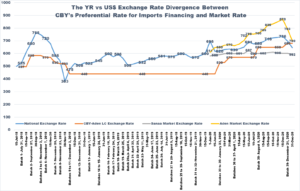

In November, the rial experienced a dramatic recovery – from trading at YR750/US$1 at the beginning of the month to YR380/US$1 four weeks later, an appreciation of almost 50 percent.[23] This corresponded with the CBY-Aden issuing a rapid series of import financing disbursements from the Saudi deposit. From November 3 to 23, the central bank issued six rounds of LCs for basic commodity imports, amounting to close to US$200 million. As the Sana’a Center reported at the time, importers took rials from money exchangers to open LCs at the CBY-Aden, enticed by the preferential exchange rate that the central bank was offering.[24] The preferential exchange rates for these six rounds of import financing were YR585, YR585, YR585, YR570, YR530, and YR520 per US$1, respectively.[25]

Other factors contributing to the rial’s recovery at that time was the delivery of US$60 million-worth of a Saudi fuel grant and Riyadh’s announcement of an additional US$200 million grant to the CBY-Aden in October. (A further US$120 million of Saudi fuel grants was delivered by January 2019.)[26]

Money exchangers also influenced, and profiteered from, the rial’s gain in value. As the Sana’a Center reported in the ‘Yemen Review – November 2018’:

“[M]any money exchange outlets acted as a cartel to buy foreign currency out of the market at a premium – meaning at a rate better than what the Aden-based CBY was offering importers. This was a purposeful overvaluation of the rial intended to absorb citizens foreign currency holdings. Simultaneously, these exchange outlets temporarily refused to sell, or severely limited their sale of foreign currency back into the market, anticipating that the rial would lose value again. On December 1, the rial depreciated – from YR380 per US$1 to YR460 per US$1 – allowing the money exchangers to sell their foreign currency for significantly more rials than they had bought it.”[27]

From December 2018 through December 2019, local currency and local commodity prices remained largely stable, according to data from, among others, the Sana’a Center, the World Bank and the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), with the former two crediting this to the underwriting of imports through the Saudi deposit. In January 2019, the Yemeni rial was trading at an average rate of YR545/US$1; by December, the value of the rial had fallen just 8 percent – its smallest annual depreciation since the conflict began – to an average of YR591/US$1.[28] Over the same 12-month period, the price of a minimum food basket decreased marginally, from roughly YR37,500 to YR36,600.[29] Of the 38 batches of import financing issued by the CBY-Aden, worth US$1.89 billion, 32 of them, worth roughly US$1.45 billion, were issued during this period of the Yemeni rial’s recovery and stabilization, from November 2018 to December 2019.

Beginning in December 2019, a confluence of factors began to weigh on the rial’s value in Yemeni government-controlled areas, and the currency re-entered a sustained period of depreciation. These included Houthi authorities announcing a ban on the use of new rial bills – printed by the CBY-Aden since 2017 – in Houthi-controlled areas, which saw these banknotes flood south into Yemeni government-controlled areas; the rial supply increased further in 2020 as the Yemeni government continued its expansionary monetary policy of printing new bills to cover expenses. Meanwhile, foreign currency inflows declined as international humanitarian funding decreased and COVID-related economic shutdowns around the region led to shrinking amounts of remittances being sent back to Yemen.[30]

The CBY-Aden, having exhausted the majority of the Saudi deposit, also dramatically reduced its import financing support in 2020. The overall total of LC financing made available throughout the year was US$509 million – roughly half the US$1.16 billion issued in 2019. Concurrently, the rial’s average monthly exchange rate in government-controlled areas depreciated steadily, from YR647/US$1 in January to YR880/US$1 in November – a 36 percent drop over 11 months. The currency hit an all-time low of YR916/US$1 on December 10, 2020, before briefly regaining ground later in the month on the back of positive political developments.[31] Meanwhile, the price of a minimum food basket increased 38 percent between the beginning of 2020 and mid-September in government-controlled areas, according to the World Food Programme.[32] At the end of 2020, just US$11.3 million of the original US$2 billion Saudi deposit remained.[33] The restricted supply of old rial banknotes circulating in Houthi-controlled areas, along with strict enforcement of policies regulating the foreign exchange market, helped the rial exchange rate in these areas stay essentially stable throughout 2020, at around YR600/US$1.

Over the course of the Saudi deposit being used to finance imports (July 2018-December 2020), it only covered a portion of the total imports of basic commodities coming into Yemen (see Figure 2 below). For example, the Sana’a Center Economic Unit estimates that in 2019, the year in which the CBY-Aden made the most disbursements from the Saudi deposit, LCs from the central bank covered only 40-to-50 percent of the total imports of rice, wheat, sugar, milk and cooking oil.

Figure 2

Source: IMF and PoE’s Report, January 2021

The Preferential Exchange Rate for LCs

In August 2017, the CBY-Aden decided to float the rial and allow its official value to be set according to the market exchange rate. As the Sana’a Center reported at the time, this came following international pressure to address currency arbitrage related to funds aid agencies were bringing into Yemen. Previously, aid agencies had to exchange foreign currency at Yemeni banks at the official exchange rate of YR250/US$1 while, by July 2017, the rial was trading in the market at YR367/US$1, a difference in value of 47 percent, which the banks could pocket.

According to former CBY Governor Mohammed Zamman, following the August 2017 decision the central bank board of directors would set the functioning rial exchange rate by taking the average exchange rate offered at the top five leading banks and top five exchange companies, after accounting for speculative influences, and subtract 10 to 15 rials (meaning the CBY-Aden would inherently value the rial marginally higher than the market). This method for exchange rate determination, however, would leave substantial room for ambiguity. First, there is no indication as to how speculative influences would be accounted for. Moreover, in times of significant currency fluctuation, the exchange rate can vary between financial outlets both within and between regions, and even according to the time of day. Thus, the exchange rate the CBY set in government-controlled areas on any particular day had to be a weighted average that accounted for these variables. How this average was weighted, however, was not clear.

In September 2018 the Yemeni cabinet issued Decree 75 to regulate the process of importing basic commodities and oil derivatives; paragraph 2a stated that “the Yemeni government and the CBY are committed to provide the foreign currency necessary to cover all credits and documentary transfers required for the five basic and declared commodities (flour, sugar, rice, baby milk and vegetable oil) at the market price for all traders and across all banks.” However, a seven-page letter from the Yemeni government’s Economic Committee interpreting Decree 75 laid out a mechanism to regulate fuel imports without setting an exchange rate policy for LCs, while the implementation of new regulations regarding food imports was postponed (See Yemen Review-October 2018.) Thus, the CBY-Aden’s previous formula for determining the official exchange rate remained the effective policy for the first eight batches of LCs the bank issued (from July through November 2018).

In November 2018, as the Yemeni rial rapidly appreciated in market value, the central bank revalued the rial higher in its LC mechanism, though not proportionally. Beginning on December 3, the CBY-Aden began offering LCs at YR440/US$1, for batch nine of the LC disbursements, and held this exchange rate constant throughout the large currency fluctuations of that month and into January.

Importantly, during periods of rapid dramatic fluctuation in the market exchange rate – for instance, the wild volatility witnessed in late 2018 – the central bank’s latitude to revalue its LC exchange rate in step with the market becomes restricted by its primary mandate to maintain price stability. Were the CBY-Aden to attempt to revalue the LC exchange rate daily, one importer whose application has just been approved could benefit substantially more or less from the import financing mechanism than another importer of the same commodity whose goods have just been ordered and are in transit to Yemen, given the delay between importers’ payment of the first half of the LC at the beginning of the application process and the second half upon the Saudi authorities’ final approval. It would also be possible that, by the time the application process was complete, an importer could find that their LC was financed at exchange rates higher than what the parallel market would have offered them. To limit these potential factors being reflected in the consumer market through increased price volatility, it is incumbent on the central bank to keep its revaluations of the LC exchange rate moderate and gradual.

Zammam, in recent public statements, detailed an official meeting in February 2019 between the CBY-Aden, the Yemeni government and its Economic Committee. At the time, the bank committee responsible for setting the LC exchange rate had revalued it to YR520/US$1 but, according to Zammam, was overruled at this February meeting by the head of the Economic Committee, Hafedh Mayad, who said that lowering the value of the rial would send a “negative indication” to the market. The outcome of the meeting was that the LC exchange rate would be officially set at YR440/US$1, a rate that held until LC batch 32 was issued, on November 21, 2019.

For the subsequent batches, issued in 2020, the CBY-Aden reverted to the previous mechanism for determining the preferential exchange rate according to the market rate, which had been in effect prior to November 2018. Thus, for January, April and August 2020 the preferential exchange rate for LCs was set at YR530, YR570 and YR650 per US$1, respectively.[34] Notably, Sana’a Center Economic Unit assessments of the exchange rates prevailing in the market at that time valued the rial significantly lower, at YR650, YR660 and YR760, respectively, an average disparity of YR107.

The Responsiveness of Commodity Prices to Exchange Rate Fluctuations

In general, commodity prices have increased quickly in periods of rial depreciation but have been far slower to decrease in periods of rial appreciation. For example, between October and December 2018, the rial appreciated in value by a monthly average of around 30 percent, from YR732 to YR518 per US$1, respectively. Over the same period, the average prices for wheat flour, wheat grain, sugar and vegetable oil in Sana’a and Aden collectively decreased by just 21 percent.[35] As the Sana’a Center observed in November 2018:

“The absence of governing authorities to supervise and regulate prices has created a conducive environment for food traders to exploit, allowing them to manipulate prices and inflate their profit margins. For instance, even with the Aden-based CBY’s importation mechanism to offer importers of selected basic foodstuffs a privileged exchange rate – lower than the parallel market rate – Yemeni citizens are not benefiting. Instead, commodity wholesalers and retailers are the main beneficiaries. According to traders based in Sana’a, retail shops were, as of the end of November, still selling commodities based on an exchange rate of YR800 per US$1, which was the exchange rate in early October when the rial had depreciated to record lows.”

As shown in Figure 3 below, over the course of the CBY-Aden initiative to fund imports using the Saudi deposit, prices for the five basic foodstuffs covered have been less responsive to the rial’s appreciation than they have been susceptible to its downward fluctuations.

Figure 3

Source: OCHA, Yemen – Food Prices Humanitarian Data Exchange (humdata.org)

Following the implementation of the LC mechanism by CBY-Aden, attempts made by both the internationally recognized government and the de facto Houthi authorities to enforce reductions in prices in their respective areas in line with the rial’s appreciation generally showed limited success.[36] Notably, market regulation in Yemen has become increasingly difficult for the authorities in either Aden or Sana’a, given the fierce competition between them for monetary and fiscal primacy.

Embezzlement Accusations Against the CBY-Aden

The Panel of Experts’ Case

In its final report for 2020, the Panel of Experts on Yemen stated that:

“[T]he Panel’s investigations have revealed that the CBY, in collusion with local banks and traders, broke the CBY’s foreign exchange rules, manipulated the foreign exchange market, and laundered a substantial part of the Saudi deposit via a very sophisticated money-laundering scheme … The CBY, headed by Governor Mohammed Mansour Zammam, violated all procedures and laws regarding the coverage of LCs from the Saudi deposit.”

These allegations center on the preferential exchange rate the CBY-Aden offered traders on LCs to finance imports. According to the figures the Panel of Experts used for their report, for the first eight batches of LCs, spanning the period July-November 2018, the average bank exchange rate given to fund food imports was YR570/US$1, compared to an average market exchange rate of YR683/US$1 over the same period. The panel reported that, from early December 2018 onward (until batch 38 was issued in August 2020, the last one covered in the panel’s report), the preferential exchange rate was fixed at YR440/$US1 while the average market exchange rate was YR557/US$1 during the same period.[37] Cumulatively, according to the panel, the result was a 29 percent differential between the average LC exchange rate and the average market exchange rate. (The Panel of Experts report excludes the CBY-Aden’s last batch of LCs, issued in December 2020, from its analysis and focuses on the period from July 2018 to September 2020, during which the central bank issued 38 LC batches, totaling US$1.89 billion.)[38]

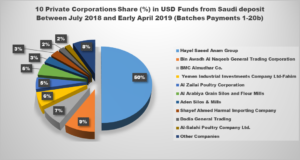

The panel says the difference between the CBY’s preferential exchange rate and the market rate facilitated the diversion of more than US$423 million from the Saudi deposit to “preferred traders” and represented “a bonanza for their business and personal wealth.” According to the panel’s analysis, of the 91 commercial companies that benefited from the LC mechanism, nine that belong to a single holding corporation, the Hayel Saeed Anam (HSA) Group, received 48 percent of the approved import financing. This would mean that HSA benefited to the tune of US$194.2 million from the preferential exchange rate alone – in addition to profiting from the sale of the goods imported. The panel says HSA was able to capture such a large share of the Saudi deposit through both general market dominance and the fact that it “place[d] ex-employees in key Government roles (including in top positions at the CBY, and in the Cabinet of Ministers)”.[39]

This alleged embezzlement came at the expense of the general population, according to the panel, because Yemenis did not see lower consumer prices from the effective subsidy the CBY-Aden was giving traders. The Panel of Experts states that:

“For example in 2019, the Yemeni rial depreciated by 23 percent versus the United States dollar. As a result, the price for the minimum food basket increased by 21 percent. The basket’s price was primarily affected by two commodities – cooking oil and sugar – which increased by 47 percent and 40 percent, respectively. Traders importing these two commodities received preferential exchange rates from the Central Bank of Yemen; however, it is very clear that this discount was not passed on to consumers. Furthermore, the international price of cereals was trading at multi-year lows, with vegetable oil traded at an 11-year low in 2019, yet their price still increased in Yemen.”[40]

The panel claimed, in its report, that CBY-Aden had violated several Yemeni laws. It asserted that in setting a preferential exchange rate for LCs, CBY Governor Mohammed Zamman had violated Decree 75 of 2018, specifically the clause that the import financing be carried out “at the market price for all traders and across all banks.”[41] The panel also stated that the central bank had “violated a number of Articles in the Central Bank Law No. 14 of 2000”[42] but did not name those articles. The report said the CBY-Aden had also violated a clause of Law No. 21 of 1991 that states that the central bank will, in its management of the country’s foreign reserves, seek to achieve “the largest possible return from dealing with highly rated banks”[43] while also applying safety standards regarding liquidity and dealing with “the Bank for International Settlements, the Arab Monetary Fund, and the World Bank to manage part of these reserves.” According to the Panel of Experts, “Central banks throughout the world are, in theory, profit-making institutions for their Governments. However, the CBY in Aden is clearly not acting in the best interests of the [internationally recognized government of Yemen] in this case.”

The Panel of Experts thus concluded that the CBY-Aden and the Yemeni government had colluded with “well-placed businesses and political personalities” to illegally transfer US$423 million in public money to private corporations. The panel deemed this a “destructive strategy” that amounted to “money laundering and corruption”, which, by impacting the population’s access to food supplies, violated Yemenis’ right to food.

Failures in the Panel of Experts’ Evidence and Arguments

Analysis Errors Misrepresent the Benefits to Yemenis from the CBY-Aden’s Import Financing Mechanism

The most glaring error in the Panel of Experts’ report is its assessment that Yemenis did not benefit from the CBY-Aden mechanism for financing imports using the US$2 billion Saudi deposit. As noted above, the period of time in which the largest share of the deposit was disbursed – November 2018 to December 2019, when US$1.45 billion in LCs were issued – witnessed Yemen’s domestic currency recover in value and stabilize, with the price of a minimum food basket also stabilizing during this time. Immediately before and after this period, the rial experienced rapid depreciation and food prices increased. As mentioned, the Sana’a Center and international organizations have noted the obvious correlation between the period in which the largest portion of import financing was disbursed and the stabilization of the domestic currency and basic commodity prices. According to a World Bank report in December 2019:

“Continued import financing support by the CBY-Aden has played a vital role in stabilizing the prices of essential food during 2019, although a range of other factors — parallel market exchange rate, political and security instability, uncertainties in trading and import arrangements, dual taxation, and fuel availability — also affect food prices.”[44]

Figure 4

Source: FAO-FSIS & MoPIC-FSTS [45]

Figure 5

Source: FAO-FSIS & MoPIC-FSTS [46]

Figure 6

A review of the Panel of Experts’ research reveals the likely source of its error regarding the benefit to Yemenis of CBY-Aden policy. The panel cites a single World Food Programme (WFP) report, from August 2020, as the source of the statistics backing their statements regarding depreciation in the rial exchange rate and increase in commodity prices for 2019, though they appear to have misread the data the WPF presented. The statistics the Panel of Experts refer to from the WFP report cover the period from August 2019 to August 2020 and not January-December 2019. Indeed, a graph in the WFP report directly adjacent to the table from which the experts likely derived their statistics clearly shows that the Yemeni rial enjoyed a period of relative stability in 2019 and then began to rapidly lose value in government-controlled areas from the beginning of 2020 to August, when the WFP published its report.

The Panel of Experts was thus incorrect in stating that Yemenis did not benefit from the CBY-Aden’s import financing mechanism through stable currency and commodity prices. It is possible that Yemenis could have benefitted from the Saudi deposit far more than they did, however, and that large-scale embezzlement has occurred.

Data and Tabulation Errors Mar Calculation of the Exchange Rate Differential Between the Market and the LC Mechanism

The panel report stated that the CBY’s average exchange rate applied to the LCs was YR455.57 per US$1, while the average market exchange rate when those LCs were issued was YR587.93 per US$1; the panel thus concluded that there was a 29 percent differential between these two rates. The Sana’a Center recalculated these numbers using the data provided in the panel’s own report[48] and found that the average CBY exchange rate for LCs – according to the panel’s numbers – was YR469.8/US$1, while the average market exchange rate of the period was YR585.6, meaning the panel should have reported a smaller differential, of 24.6 percent. When applied to the US$1.89 billion issued in LCs for the period discussed, this tabulation error amounts to more than US$83 million.

A deeper problem, however, is that the numbers that the panel used in its (mis)calculations also contained numerous errors. A Sana’a Center review of the data points the Panel of Experts used to calculate the differential on each of the 38 batches of LCs covered in the report found 16 errors, where the panel used either the incorrect market exchange rate in Houthi-controlled areas, the incorrect LC exchange rate, or in several instances both rates used were incorrect.[49] While the panel calculated the overall amount of potential arbitrage at US$423.2 million, the Sana’a Center recalculated this figure at US$323 million – using the relevant exchange rate in Houthi-controlled areas at the time – an error of roughly US$100 million.* The Sana’a Center corroborated all figures against those in the central bank’s internal accounting system, which recorded the exchange rates at the time of each transaction. The panel cited “CBY Aden & Panel” as the source of its figures.

Further muddling the Panel of Experts’ calculation of the exchange rate differential between the market and the LCs was the panel’s use of the market rate in Houthi-controlled areas only, rather than the average national market rate. As mentioned above, at the beginning of 2020 an accelerating divergence emerged in the value of the rial between Houthi- and government-control areas, rising from 10 percent in January to nearly 30 percent in August, when the last LC disbursement the panel looked at was made. This is particularly salient in regards to import financing given that the Houthis control the country’s largest population centers and its largest markets. Areas under the group’s control are thus the destination for the lion’s share of the imports financed under the LC mechanism. A more reflective calculation for the differential between the CBY-Aden and market rates from January 2020 onwards, therefore, would have used the average national exchange rate.[50] The Sana’a Center recalculated the potential arbitrage profits that could have been made from funds disbursed from the Saudi deposit in this period using the national average exchange rate. The resulting figure was US$347 million, meaning that the panel erred by at least US$76 million in its assessment.

The Panel of Experts’ determination that HSA specifically received 48 percent of the $1.89 billion Saudi deposit in import financing was also an error. As part of HSA conglomerate the panel included Aden Silos & Mills, a company that is neither owned nor operated by HSA Group.[51] The company, which received US$32.5 million in foreign exchange funds via the LC mechanism, is a subsidiary of the Al Rowaishan Group, one of Yemen’s other large commercial business groups. In reality, HSA received 45 percent of the Saudi deposit – an error of 3 percent on the part of the panel.

Misunderstanding the CBY-Aden’s Legal Mandate

The Panel of Experts appears to have fundamentally misunderstood the CBY-Aden’s legal mandate. The Law on the Central Bank of Yemen (No. 14 of 2000) superseded all previous legislation pertaining to the central bank. In Article 5, it states unequivocally: “The primary objective of the Bank shall be to achieve and maintain price stability.”[52] Among other things, the law mandates that the CBY execute a monetary policy consistent with this primary objective and set its foreign exchange rate regime “in consultation with the Government”.[53] The mandate of “price stability” requires the central bank to act in favor of the public interest, rather than act as a “profit-making” institution for the government (as the panel claims is typical of central banks), which would seem generally at odds with achieving macroeconomic stability in Yemen.

It appears that the panel based its analysis on a misinterpretation of articles from outdated CBY Law No. 21 of 1991, specifically citing an article that states the CBY is to apply:

“Effective management of external reserves with safety standards – liquidity – and achieving the largest possible return from dealing with highly rated banks in order to obtain the highest possible return while observing the safety factor. And dealing with the Bank for International Settlements, the Arab Monetary Fund, and the World Bank to manage part of these reserves.”[54]

In its assessment, it appears that the panel confused the issues of the CBY’s management of its external reserves with its primary mandate of maintaining price stability. The CBY-Aden should indeed act as a profit-maker for its government when dealing with international financial organizations, such as the Bank for International Settlements, the Arab Monetary Fund, and the World Bank, because by law it is acting to manage the country’s foreign exchange reserves as the banker, advisor and fiscal agent of the government. To this end, the CBY had invested much of its reserves in portfolios at the IMF, World Bank and other international institutions to generate profit. However, this is in support of, rather than at the expense of, pursuing its primary mandate of achieving price stability.[55]

The panel is also incorrect in stating that Governor Zammam’s implementation of the preferential exchange rate was illegal. Because Decree 75 of September 2018 mandated that the LCs be issued “at the market price”, without setting an explicit exchange rate policy, the previously established mechanism for determining the market price, set in August 2017, was in effect. Namely, the central bank took the average of the exchange rates at the country’s top five banks and top five money exchangers, adjusted for speculation and subtracted YR10 to 15. This mechanism for determining the central bank’s functioning market rate inherently builds in a marginal differential with what the rial is actually trading for at banks and money exchangers – though, as mentioned above, ambiguity remains regarding both how the CBY-Aden adjusted for speculation and gleaned the rate from the market. Thus, it seems likely that Governor Zammam was technically within his legal remit in setting the CBY-Aden’s preferential exchange rate until February 2019 when, as also mentioned above, the CBY-Aden, the Yemeni government and its Economic Committee officially made the policy decision to hold the LC exchange rate steady at YR440/US$1. The previous floating exchange rate mechanism then came back into effect after accelerating exchange rate divergence between Houthi- and Yemeni government-controlled territories in December 2019/January 2020 made the fixed LC exchange rate untenable.

Specific Conclusions Deeply Flawed; General Concerns Still Warrant Consideration

The Panel of Experts’ errors regarding basic data, tabulated calculations, timeline analysis and legal interpretations effectively torpedo the report’s specific claims against the CBY-Aden, the Yemeni government and commercial importers. However, the general issues the report raises regarding elite capture, lack of transparency and possible corruption involved in the CBY-Aden’s import financing mechanism warrant serious consideration, as will be discussed below.

Salient Concerns Regarding the CBY-Aden

Questions of Elite Capture

The wide spectrum of commercial and financial actors in Yemen have shown a persistent tendency to seek out opportunities for arbitrage in the buying and selling of goods or currency. At times, various actors have colluded to manipulate the market for mutual benefit – for example, the aforementioned money exchanges in the fourth quarter of 2018. However, that arbitrage is occurring at any given instance does not, in itself, entail that collusion is occurring nor allow for the specific identification of the actors involved. Widespread economic collapse and the erosion of effective regulation during the conflict have given rise to intensely predatory market dynamics. The pressure to which the Houthis have increasingly subjected financial institutions and businesses to not comply with the stipulations regarding the CBY-Aden’s LC mechanism has acted as a large disincentive against engaging with this mechanism. The CBY-Aden has been open about using the preferential exchange rate as an enticement to outweigh this disincentive. In an environment in such turmoil, lines are often blurred between corruption, collusion, coercion and attempting what is deemed necessary with the dynamics at hand to achieve desired market outcomes.

Cabinet Decree No. 75 was introduced as suggested policy by the Economic Committee and the CBY, according to a senior-level banking official aware of internal discussion surrounding the LC mechanism. The decree was, at best, ill conceived, given that it established a non-competitive trading mechanism by restricting foreign exchange to finance the import of just five basic commodities. Other foods were excluded from the mechanism, while sugar, which is used as an input for many non-staple commodities such as candies, was granted support in the LC mechanism. The restricted eligibility criteria for LC suport indirectly granted a limited number of commercial traders a special privilege to monopolize the lion’s share of foreign exchange funds available from the Saudi deposit. It also ran contrary to the original Saudi deposit agreement which allowed for the establishment of a competitive mechanism under which importers of all basic commodities, including foodstuffs as well as medicine, should be able to apply for foreign exchange financing from the deposit.[56]

Several factors contribute to the monopolization of foodstuffs in Yemen, including the fact that the food import market has been historically dominated by a small number of private corporations, as well as the constraints and difficulties recently linked to meeting the requirements of the CBY-Aden’s LC system. In 2014, four subsidiary companies of HSA Group – historically Yemen’s largest business conglomerate – dominated 52.5 percent of the local market in wheat flour.[57]

In 2018, HSA’s market share in Yemen for key commodities was estimated at more than 50 percent; the group’s share of the Saudi deposit mechanism could thus simply track with its dominant market share and reflect its decades-long history of supplying key commodities and staple goods to the Yemeni market.[58] The panel stated that HSA Group’s vast presence in the country via numerous businesses in different sectors, years of know-how, and ability to access foreign markets and suppliers grant it a comparative and competitive advantage versus other commercial traders, which allowed it to capture a large share of the deposit. In addition, the panel stated that another factor in helping HSA secure its share of the Saudi deposit was the fact that it had ex-employees in top positions at the CBY-Aden and in government. CBY-Aden Deputy Governor Shakeeb Hobishi was formerly employed by HSA Group; Hobishi arranged for his son-in-law, Shadi Mohammed Abdulqawi Saif, to be appointed the CBY-Aden director of international operations and development. To date, however, there is no evidence that HSA Group had Hobishi or others “placed” in their positions at the central bank or in government, as the panel asserted.

That said, in Sana’a Center interviews with various food importers between December 2018 and February 2019, several complained that the CBY-Aden was giving preferential treatment to certain importers by processing their applications much quicker than others.[59] According to a credible banking source interviewed by the Sana’a Center Economic Unit, the Yemen Industrial Investments Company Ltd, owned by prominent businessman Mohammed Fahem, threatened to sue the CBY-Aden administration through investor-state dispute settlement for the alleged unfair exclusion of the company’s request for foreign exchange financing of US$118 million, under LC batch 30, issued in September 2019.

Between the end of July 2018 and early April 2019, 10 corporations and business groups received $865.7 million in foreign funds, in total, from 2o batch payments from the Saudi deposit. HSA Group received 50 percent of these total funds.[60] It should be noted that HSA Group received import financing for commodities that were also inputs for its factories in Yemen – which require items such as sugar, oil and wheat flour to produce candy and other food items – whereas most other importers would sell all of their unwritten goods into the market as is.

Figure 7

Source: CBY-Aden, UN Panel of Experts[61]

Based on the provisions of Law No. 19 of 1999, “concentration is prohibited if it leads to restrained or weakened competition.”[62] According to the law, a monopoly is achieved when a company’s market share exceeds 30 percent of the total supply of a particular commodity in the market in which the company operates.

Lack of Oversight, Crippled Governance, Political Infighting and Allegations of Corruption

As an institution with theoretically national purview, the CBY-Aden – since being relocated to operate from the interim capital of the internationally recognized government – has failed to assert authority even over its branches located in government-controlled territories. Branches in Marib and Al-Mahra governorates, for instance, have continued to function semi-independently from the center in their collection of locally generated revenues and adoption of monetary policy-linked mandates (See ‘The Struggle to Rejoin a Divided Central Bank’ in ‘War’s Elusive End – The Yemen Annual Review 2019’).

Adding to the institutional disarray and undermining the central bank’s ability to maximize the utility of its foreign currency reserves, including the Saudi deposit, have been the deeply entrenched divisions among various institutional bodies and the personnel associated with administering and supervising CBY-Aden operations. Some of the most significant divisions hampering central bank functions include those: within the bank’s executive management and subordinate sectors; between the bank and its board of directors; between the Yemeni government’s Supreme Economic Committee and the bank’s executive management; and between these two bodies and the central government, which, following the bank’s relocation to Aden, failed to create non-partisan, institutionally harmonious administration to assist the implementation of monetary policy functions.

The CBY-Aden’s administrative splintering began immediately following its relocation to the southern port city, but intensified with the arrival of the Saudi deposit. Indeed, conflicts over exchange rate policy management were long evident in the divergent views and acrimonious exchanges between Mohammed Zammam, governor of the CBY-Aden from February 2018 to March 2019, and Hafedh Mayad, who headed the Yemeni government-affiliate Economic Committee during Zammam’s tenure. Mayad then replaced Zammam as CBY-Aden governor, while also remaining head of the Economic Committee, until September 2019. He was then replaced as central bank governor and made a consultant to the Yemeni president.

In January 2019, Mayad directly accused Zammam’s central bank administration of being involved in foreign exchange corruption. In a letter to the Aden-based Supreme Authority for Combating Corruption (SACC), Mayad claimed the CBY-Aden had diverted approximately YR9 billion (equivalent to roughly US$14.4 million, at the time) through purchasing almost 450 million Saudi riyals from the local market at an above-market price to fund LCs for basic commodities. Mayad asked the SACC to intervene and investigate, but his allegations were subsequently shown to be unfounded: the exchange rate differential resulted from the significant appreciation the rial experienced during November 2018 and the delay of up to 48 hours between the time at which the bank agreed to the price and the time at which the actual trade was conducted.

One month later, according to Zammam, the Yemeni government and the Economic Committee intervened in the central bank’s operations and disrupted the currency market. Zammam accused Mayad of backing the overvaluation of the Yemeni rial at a fixed preferential exchange rate of YR440/USD, significantly below the market rate, to finance a total of 24 batches of LCs, amounting to $1.25 billion, from the Saudi deposit. Drawing on the Panel of Experts’ data, during the administration of Mayad, from March 20 to September 18, 2019, some US$757 million, or 40 percent, of the total 38 batches ($1.89 billion) was disbursed from the Saudi deposit at the preferential exchange rate of YR440/US$1. (Notably, the Panel of Experts report mentions Zammam by name, but not Mayad.)

On January 14, 2020, Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed formed a Supreme Economic Council headed by himself and including the governor of the central bank and the ministers of finance, oil, and planning and international cooperation. The first decision taken by the Supreme Economic Council was to withdraw powers from the Economic Committee, headed by Mayad, particularly with regard to the LC mechanism and regulating imports.

Recent media reports have also asserted that massive corruption has taken place at the central bank through currency arbitrage. On January 12, 2021, Al-Wattan newspaper reported on a leaked memorandum, dated September 15, 2019, in which three members of the board of directors at the CBY-Aden – Jalal Fakirah, Shakib Hobeishi and Sharaf al-Foadei – notified President Hadi regarding multiple violations and corrupt practices that occurred during Mayad’s administration. The report accused Mayad of suspicious and speculative foreign currency transactions with a number of money exchangers and CAC Bank, whose Board of Directors Mayad had chaired before the outbreak of the current conflict. According to this memorandum, Mayad’s administration could be responsible for squandering more than US$975 million through unwarranted interventions in the exchange rate. The leaked memo pointed to unjustified exchange rate differentials that were granted to specific money outlets and CAC Bank; these institutions acted as intermediaries in CBY-Aden transactions amounting to YR3.5 billion over a period of only three and a half months, without getting the needed approval from the CBY-Aden board of directors.

Further accusations against Mayad in the memorandum included: wasting the Saudi deposit by granting commercial traders large financial credit facilities estimated at 70 percent of approved LCs without asking them to deposit cash at the CBY-Aden until the goods arrived at Yemeni ports; speculating in the exchange market outside the internationally recognized government’s areas of control; attending only one board of directors meeting, in clear violation of the CBY bylaws, while using his loyalists on the board to disrupt other meetings; and making administrative changes and creating entities, committees and boards outside the bank’s institutional structure and without the approval of the board of directors.

The Sana’a Center Economic Unit’s assessment is that the sharp administrative divisions within the CBY-Aden have resulted from the government’s failure to appoint competent, politically unaffiliated technocrats to manage monetary policy. Instead, the central bank and the operations of its various administrative components have become subject to the struggle between political parties and economic elites represented within the internationally recognized Yemeni government. While it is currently difficult to confirm the validity of any of the accusations, absent a rigorous and impartial investigation, new efforts have been launched to investigate the CBY-Aden’s activities since the Panel of Experts’ report was released. On January 31, 2021, Sultan al-Barkani, president of the Yemeni parliament, ordered a committee of financial experts and officials to investigate and audit the bank’s activities, including by interviewing bank staff, and subsequently present him with their findings. Also, on February 7, Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed announced that the Yemeni government hired Ernst & Young to audit the CBY-Aden operations. There has also been opposition to these efforts. On February 17, 2021, the current CBY-Aden governor, Ahmed Obaid al-Fadhli, through a memorandum addressed to the chairman of the Supreme National Anti-Corruption Commission (SNACC), refused to allow SNACC to conduct an investigation into the bank’s operations, stating that it does not fall within the commission’s jurisdiction, under the provisions of Central Bank Law No. 14 of 2000.

Since the transfer of the CBY’s administration from Sana’a to Aden, there has been a great deal of ambiguity and opacity regarding the bank’s operations. The CBY-Aden has lacked the necessary monitoring and accountability framework to ensure funds disbursed from the Saudi deposit met the desired goal of maintaining food price stability. The LC mechanism had no control and compliance features, with there being oversight over neither activities in Yemen nor the Saudi authorities approving each batch. There has been neither an external or internal audit of the CBY-Aden since its relocation to the interim capital in September 2016. For the past four years, the CBY-Aden has not even published its annual financial statements; this is in direct violation of International Standard No. 30 and also in violation of Article 57 of the CBY law, which clearly states: “Within three months of the end of the fiscal year, the bank shall present to both the House of Representatives and the Council of Ministers the following: a copy of its annual budget certified by the two references and a report on the economic situation in the country and on the bank’s affairs and operations during that year.”

What has made central bank operations further opaque, created more space for illicit dealings, contributed to currency divergence, and highlighted the dysfunction of the CBY-Aden’s monetary policy is its use of four different exchange rates in its internal operations – none of which are the actual rate at which currency is being bought and sold in the market. First is the internal evaluation exchange rate, which applies to budget accounting and transactions between the CBY-Aden and the Yemeni government – mostly the Ministry of Finance – and has been set between YR370 and YR400 per US$1 since mid 2017; second is customs valuation rate which is set at YR250/US$1; third is the preferential exchange rate used for imports of the five food commodities financed from the Saudi deposit, which is set according to the aforementioned market rate mechanism, and was set at YR440/US$1 throughout 2019; fourth is the preferential exchange rate approved since April 2019 under another LC mechanism for financing importers of oil derivatives and other basic commodities not covered by the Saudi deposit (other foodstuffs, medical supplies, building materials, fabrics, and clothes) at a preferential exchange that is rate lower than the parallel market rate, higher than the rate used for financing imports from the Saudi deposit, and was for the most part valued at YR506/US$1.

The differential between these rates, which allows the same cash holdings within the CBY-Aden to be evaluated at different rates, depending on usage, has allowed for “value” to be created essentially out of thin air. For instance, the Sana’a Center Economic Unit estimates that the differential between the evaluation exchange rate in the CBY internal accounting system and the preferential exchange rate given to finance food commodities has, between July 2018 and December 2020, led to the creation on YR111 billion on the central bank balance sheet, which is then counted as the Yemeni government’s share of the central bank’s net profit.

As mentioned, a rigorous and impartial investigation is needed to determine the scope and scale of any embezzlement of public funds from the Yemeni central bank that may have occurred. What is clear, however, is that in the light of deep divisions over the central bank’s management, and absent minimum standards for transparency and accountability in the operations of the CBY-Aden, there has been, and continues to be, a vast window of opportunity for corruption to arise.

Looking Ahead: Implications of the Panel of Experts Report

The CBY-Aden is currently in a monetary and foreign exchange crisis, after having depleted almost all of its foreign currency reserves. Over the course of 2020, the CBY decreased its financing of the country’s basic commodity imports, limiting its foreign currency interventions in the market. Consequently, the Yemeni rial depreciated to all-time lows: it was valued at less than YR900/$US1 as 2021 began.

Since the onset of the current conflict, and particularly from 2018 to 2020, Saudi Arabia has been the largest financial backer of the Yemeni government; more than US$2.5 billion in bilateral support – including the US$2 billion deposit – has been channeled from Riyadh through the CBY-Aden to help in economic stabilization. Even before the Panel of Experts report was published in January 2021, Saudi Arabia had been clearly reluctant to renew its large-scale financial support for the Yemeni government; the report’s accusations of corruption and money laundering against the CBY-Aden will only make the authorities in Riyadh less inclined to assist. To even begin to court renewed direct external support, there will likely need to be comprehensive leadership and governance reforms at the CBY-Aden, a mending of the factionalism between the parties in the anti-Houthi coalition, and an overhaul of the bank’s monetary policies.

Prior to the Panel of Experts report being published, the internationally recognized Yemeni government had, with help and technical support from the World Bank, made some progress toward persuading donors and international humanitarian organizations to channel their transfers of humanitarian aid funding into Yemen through the CBY-Aden. Such a re-routing of aid funds would allow the central bank to monitor foreign exchange flows and help it direct cash circulation back to the formal banking sector and out of the informal economy, strengthening the CBY-Aden’s ability to achieve exchange rate stability. The findings of the Panel of Experts report, however, will likely weaken donors’ confidence in the Yemeni government’s ability to mediate the payment of humanitarian aid funds over the Yemeni banking system, and could postpone their support for the new government.

Officials in the Yemeni banking sector have told the Sana’a Center Economic Unit that, while the impact of the report was not immediate – they had been able to navigate the global financial system and make international transactions as before – they are becoming subject to more intense compliance procedures related to anti-money laundering statutes from the global financial institutions they deal with. These new measures could potentially make doing banking business to and from Yemen more cumbersome and costly – and much riskier.

Yemen is currently experiencing among the worst humanitarian crises in recent decades – the UN estimated in February 2021 that 20.7 million Yemenis, some 66 percent of the population, will be in need of humanitarian assistance this year, with 12.1 million in acute need.[63] The country remains dependent on imports for 90 percent of its basic food intake. If the CBY-Aden is not able to secure new foreign exchange support to restart import financing, importers will turn to the market to purchase their foreign currency – and the Yemeni rial’s value could drop to YR1,000/US$1 before mid-year. The economic consequences of this would be further erosion of local purchasing power and increased market prices for basic commodities, which would have direct and immediate negative implications for the humanitarian situation, pushing the affordability of life’s basic necessities further beyond the reach of most Yemenis.

Recommendations

There is currently a crisis of confidence regarding the Yemeni government’s central bank. Yemenis, and the international stakeholders who would support the country, need to see dramatic and immediate action taken to begin restoring faith that this crucial institution can and will carry out the country’s monetary and fiscal policies in a principled, transparent and accountable fashion.

To this end, the internationally recognized Yemeni government should immediately:

- Dismiss the CBY-Aden’s entire senior leadership and board of directors and undertake a process to fill their positions with highly qualified, politically unaffiliated technocrats with a demonstrable record of upholding the public interest.

- Order comprehensive, independent audits of all central bank operations – expanding the mandate of the current Ernst & Young audit if necessary and appropriate for accomplishing this task. Upon completion, the full results of the audits should be made public.

- Appoint an independent investigative committee to examine all transactions related to the Saudi deposit and the central bank’s sales and purchases of foreign currencies.

- Launch criminal investigations and prosecutions against any individuals suspected of violating Yemeni laws, and the central bank law in particular, in any aspect of their work or dealings with the CBY-Aden. Specifically, each of the four individuals who have held the post of governor at the CBY-Aden since its relocation from Sana’a in 2016, all members of their respective administrations, and all members of the board of directors should be investigated for possible criminal wrongdoing.

- Begin exploring plausible policy options to foster competition and limit the oligopolistic and monopolistic tendencies of the Yemeni market.

As soon as possible under the new senior leadership and board of directors, the CBY-Aden should:

- Immediately publish all data detailing the share of the Saudi deposit each Yemeni importer received.

- Initiate comprehensive governance measures to reform the CBY-Aden’s institutional and organizational structures, develop its monetary policy frameworks and strengthen accountability and transparency mechanisms. This must include an overhaul of the central bank’s import financing system to include accountability and transparency mechanisms that meet international standards.

- Adopt a unified, free-floating managed exchange rate policy and scrap the current use of multiple exchange rates for internal accounting and intragovernmental financial transactions. The new exchange rate policy should take into consideration the bank’s currently weak foreign currency stocks and attempt to influence the supply and demand sides of the foreign exchange market indirectly through systematically planned and well-studied interventions.

- Begin the necessary procedures to publish its financial statements and disclosures linked to them since the central bank was relocated to Aden in 2016.

- Resume publishing of its monthly monetary and banking developments bulletin and annual report. The CBY-Aden should adopt clear transparency measures to publish, on a regular basis, all data and information relating to its exchange rate and monetary activities, decisions related to the financing of LCs and the importers benefiting from them, as well as financial sector market data and activities.

The HSA Group is the country’s largest conglomerate. With a longer history than that of the republic itself, HSA Group is a standard bearer for Yemen’s commercial and private sectors generally and thus the restoration of its reputation is in the national interest. Given this, HSA Group should:

- Release all data regarding its use of the LC mechanism, specifically detailing HSA’s pricing data for commodities, and products that used commodities imported via LCs, sold in Houthi-controlled areas and in Yemeni government-controlled areas, to allow for transparency regarding HSA’s potential benefit from the market exchange rate and the rate received under various LCs.

- Commission an independent audit of all HSA Group’s activities related to its companies’ use of the CBY-Aden’s import financing mechanism and from any other source of foreign exchange intersecting with it.

- Release and publicize the full findings of this audit once it is complete to demonstrate the group’s commitment to transparency and accountability.

The UN Panel of Experts on Yemen should immediately:

- Initiate a review of their 2020 annual report to correct errors and issue a public correction.

- Review the methodology by which the panel arrived at its erroneous figures and conclusions and make the necessary adjustments to avoid such errors in future reports.

- Seek out and retain Yemeni expertise to assist with compiling and assessing information and data for its reports. The Panel of Experts is entirely non-Yemeni and clearly lacks an informed, and sometimes even basic, awareness of the local context.