Introduction

The question of border demarcation has been one of the most contentious issues in the historical relationship between Yemen and Saudi Arabia. Border disputes have been at the heart of many of the tensions between the two countries over the past century. They fought over the border in 1934, resulting in the Treaty of Taif, a non-permanent agreement that reflected the will of Saudi Arabia. But the border was to remain a source of conflict into the 1990s, which saw a number of military skirmishes.

When an international agreement eventually ending the dispute was signed in 2000, a series of joint Saudi-Yemeni committees were established to examine security and development issues related to the border, such as watchtowers, joint patrols and rules for construction work in the area. However, the beginning of the Sa’ada wars in northern Yemen between the Sana’a government and the Houthi movement in 2004 made the border work too difficult to continue. At the same time, the border continued to be a source of disquiet. For Saudi Arabia it was a source of arms, drugs and qat smuggling, while Saudi Al-Qaeda figures were able to cross into and find refuge in remote regions of Yemen. In 2009, Saudi Arabia became directly involved in Sana’a-Houthi military confrontations after Houthi incursions into Saudi territory.[1]

Following the ouster of President Ali Abdullah Saleh in 2012, Saudi Arabia revived plans to erect a fence along the entire 1,460-kilometer frontier from the Red Sea coast in the west to Oman in the east but made limited progress.[2] Later, after the Houthi seizure of Sana’a in September 2014, Riyadh and its allies launched a full-scale war to reinstate President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi’s government. Seven years of war has shattered social and economic bonds since many communities exist on both sides of the border.[3] It has become more clear than ever that securing the frontier is the most critical element in attaining a permanent peace: there cannot be stability between the two countries if the border issue is not permanently resolved.

This paper argues that the dormant border committees formed two decades ago should resume their activities as soon as possible. This should be done with the support of the United States and Oman, the international partners who cooperated with the committees before their work ground to a halt around 2004. The paper makes use of the minutes of meetings from 1995 to 2008, as well as the experience of one of the two authors of this report, Muhsin Ramadan, who served on many of the bodies working on the issue before and after the 2000 border agreement. It offers a number of recommendations, the most important of which is to reform the joint Saudi-Yemeni committees, including the key military and security committees. These committees should form the basis for action as soon as possible to stabilize the border region, allowing residents to return and Yemen and Saudi Arabia to resolve their difficult relationship – a prerequisite for sustainable peace.

Background: Decades of Tension over Disputed Border

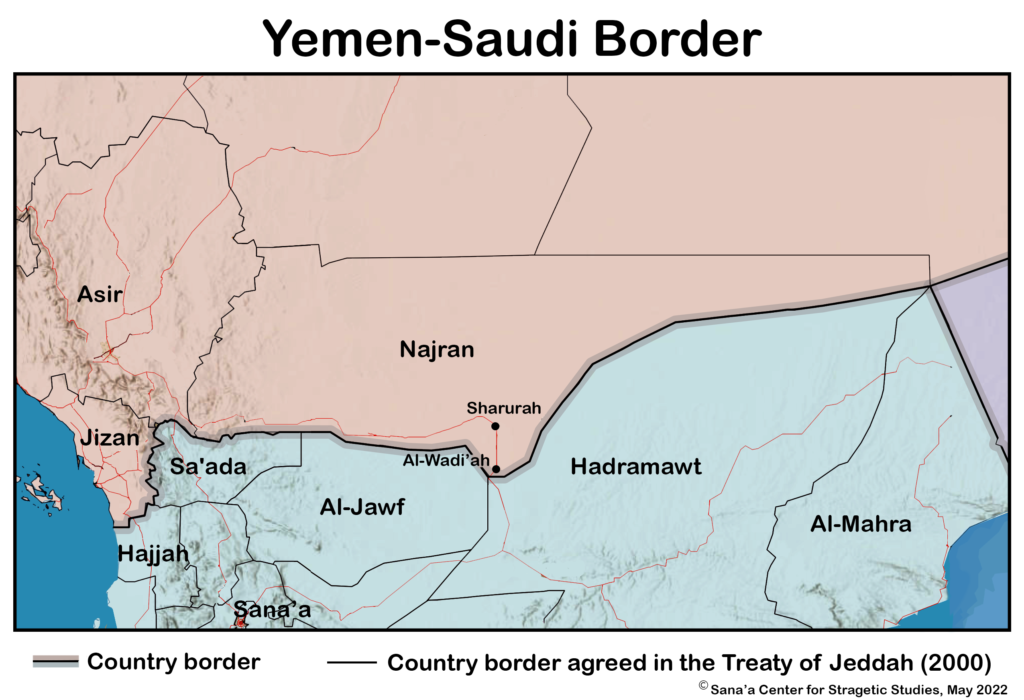

The border dispute between Yemen and Saudi Arabia is one of the longest such disputes in the world, lasting seven decades from war in 1934 to the Treaty of Jeddah in 2000. Following the Ottoman defeat in the First World War and its withdrawal from Yemen, the Yemeni imamate based in northern Yemen and the nascent Saudi state both came to claim territory, including the areas of Najran, Jizan and Asir. In 1934, Saudi Arabia won control of most of those territories in a border war, following which the Treaty of Taif formalized the situation on the ground.[4] The terms of the agreement were set for 20 years, after which it would be automatically renewed for another two decades unless one of the two countries requested a change.

In Yemen, the treaty was viewed as an unjust solution imposed by force. The agreement notably remained limited to the border between Saudi Arabia and North Yemen, setting aside the longer border with South Yemen, which had been in place since the British occupation. Riyadh would take control of more Yemeni land from time to time, taking advantage of the political instability of its southern neighbor. Saudi Arabia waged a war against recently independent South Yemen in 1969,[5] which resulted in the Saudi annexation of Al-Wadi’ah and Sharurah areas of Hadramawt governorate.

Border clashes continued even after the unification of North and South Yemen in May 1990. The Saudi position at the time was that the border question should remain split into two separate files, one with the north and one with the south. New rounds of Saudi-Yemeni talks began 1992, but with no result.[6]During the war of May-July 1994, Riyadh supported the failed southern secession declared by Vice President Ali Salem al-Beidh, believing that having an independent authority in Aden would improve its negotiating position over the border. Saudi and Yemeni forces later clashed in January 1995 in the area of Orouq bin Hamoudah, on the eastern part of the border in Hadramawt governorate. At this point, Syrian mediation not only helped prevent the clashes from turning into a wider war but succeeded in convincing the two governments to restart a negotiation process,[7]using the Treaty of Taif as a basis for solving the border dispute.[8]

As a result, a Memorandum of Understanding signed in February 1995 led to the formation of the Supreme Saudi-Yemeni Committee to oversee the process of resolving the border issue.[9] This foundational body was able to get to work quickly, creating a joint military committee to resolve urgent issues and remove military positions on both sides of the border.[10] This allowed for continued negotiations that led to the signing of the final border agreement between the two countries in Jeddah in June 2000. The Supreme Saudi-Yemeni Committee continued functioning until border demarcation was completed on the ground and new maps were exchanged. At this point, a series of joint committees were formed to implement the security and economic aspects of the agreement.

The Joint Yemeni-Saudi Military Committee (1995-2008)

A military body was formed by the Supreme Saudi-Yemen Committee during a meeting in Riyadh on December 17, 1995. Its main function was to remove military establishments on both sides of the border, based on the memorandum of understanding signed earlier that year. The military committee held 13 meetings in the lead up to the signing of the Treaty of Jeddah in 2000[11] and consisted of three levels.[12]

The top-level military committee brought together the chiefs of staff of the armed forces of the two countries. It was able to hold 19 meetings during the period 2000 to 2008. At that point the ongoing Sa’ada wars in northern Yemen and deteriorating relations between Riyadh and President Saleh caused the body to cease functioning.[13]A second level consisted of the command of the adjacent military regions of the two countries; it received reports from the inspection committees (the third level) and submitted issues to the first level. The inspection committees, established in July 2000, directly managed the situation on the ground. They supervised the removal of military sites within 5 kilometers of the border on both sides, with the exception of the security patrols, which were not permitted to carry weaponry heavier than 12.7 mm ammunition automatic rifles.[14] If the inspection committee in one country received a report concerning buildings that violated the agreements, it would inform its counterpart committee in the other country and carry out an inspection. This modus operandi built trust between the two sides and helped achieve a new level of border stability – a key reason why reactivating the military committee should be a priority.

Joint Border Committees

The 2000 Treaty of Jeddah[15] demarcated the border, providing clarity for the two countries to put an end to the long dispute. The agreement included military, economic and security arrangements to tackle issues such as smuggling, development projects and observation towers, via the work of the joint inspection committees in the early 2000s. However, despite initial positive results in implementing the border agreement,[16] a host of issues remained unresolved. These included: a draft agreement to organize border authorities;[17] a project to build a Yemeni border force;[18] regulation of grazing on the border areas; and a project to establish patrol routes and observation towers on both sides of the border.[19]

The joint committees began meeting in May 2001, a year after the border agreement was signed. Like the military committee, they also consisted of three levels.[20] The top-level body, the Committee for Regulating Border Authorities, was headed by the two ministers of the interior who were meant to hold meetings on an annual basis, or as needed. This body was responsible for managing the core issues as well as “resolving disputes, issues and incidents in the border areas”.[21] Technically still in operation, its mandate automatically renews every five years if neither party raises objections.[22] At the second level of each committee, the Saudis were represented by the director general of the Border Guard and the Yemenis were represented by the deputy minister of interior for the security sector. The third level of each committee included the commanders of the border guards in each area, which held regular meetings every six months.

According to the draft agreement, the border authorities were meant to operate at different levels to prevent illegal border crossings, shootings and other violent incidents, maintain clear border markings that remain in place, protect water resources, and address fishing issues and sea pollution.[23]They were charged with combating smuggling, regulating grazing and exchanging information on other issues such as natural disasters and epidemics.[24]

During their few years of work, the committees discussed and resolved a range of issues, some of which saw implementation. However, most projects were only carried out independently on the Saudi side of the border due to joint committee disputes over financing joint projects. For example, the committees were unable to move ahead on plans to create patrol routes along the length of the border whose costs would be covered by Saudi Arabia after 350 border vehicles provided to Yemen by the United States were used elsewhere. For similar reasons, there was no progress on plans to establish a Yemeni border force of some 15,000 personnel, build observation towers along the border and erect barbed wire to deter movement between the two sides in areas difficult for security patrols to access.

Yemen assigned border guard functions to tribal leaders in the border areas, giving the tribal leaders significant power and influence at the expense of formal entities, including the prerogative to recruit and manage personnel.[25] Saudi Arabia and Yemen also agreed on paper to exchange information over all travelers entering each country through any border point (the documents did not specify the nationality of travelers). Each country was meant to detain and extradite wanted figures.[26]A mechanism for resolving disputes was put in place through a system of memos referred to lower committees for resolution, or if necessary, the Supreme Saudi-Yemeni Committee.[27]

A preliminary agreement was also reached to regulate grazing on both sides of the border. This was based on both the Saudi-Yemeni border agreement as well as the arrangement in place on the Yemen-Oman border since 1992, by which pastoralists have identification cards allowing them to cross into joint grazing areas. In these areas, 20 km from the border on either side, pastoralists would be permitted to carry firearms as long as an inventory of their ammunition was conducted upon their entry and exit from the grazing areas by members of the border guard. There were also proposals under discussion regarding joint markets for agricultural and animal products produced near the borders and establishing free markets in selected areas. The idea was that free zones would promote commercial activity and create work opportunities for border residents, reducing reliance on smuggling.[28] But in some areas of the border the presence of people and buildings emerged as a dispute: After a property survey was conducted by both countries Riyadh suggested the creation of buffer zones, with compensation for property owners, but Yemen objected.[29]

Conclusion

Envisioning a resumption of the work of the joint committees need not wait until the war ends. This should take place independently of political developments with the aim to produce proposals that can be implemented easily once the conflict is over, or amended with minimal effort. Reestablishing the committees is the most efficient avenue for stabilizing both the border and the relationship between the two countries. This would require cooperation between the internationally recognized government and Houthi authorities, which is currently impractical and could only be realized in the event of a final political settlement.

The border could become an area of opportunity for further cooperation between Yemen and Saudi Arabia, or it could become a greater security threat. Attention to residents’ interests will be key to removing the risks associated with the many remaining border issues. Specifically, an uninhabited buffer zone, as Saudi Arabia has proposed,[30] would prevent cooperation and communication between communities on either side of the border and cause further displacement of the population while leaving unused a vast area of land. Continuation of the current situation risks exacerbating the spread of terrorism, drugs and arms, which both sides fear, creating new tension in Saudi-Yemeni relations. Development, on the other hand, would turn a security liability into an opportunity for the two countries.

Recommendations

To the Yemeni and Saudi governments:

1 – On the Military Committee:

- Review the legislative situation and procedural regulations in place with a view to putting the agreements and understandings back into operation.

- Assess the situation on both sides of the border, removing any military constructions that violate the border agreement and its annexes.

- Coordinate with the security committees over border guards.

- Organize a joint moral guidance campaign to mitigate the impact of the ongoing conflict on border personnel and boost cooperation.

- Modernize inspection mechanisms to report on violations of the agreement relating to military personnel on both sides.

2 – On Security Arrangements:

- Activate the Committee for Regulating Border Authorities, headed by the two ministers of interior, and its subcommittees. This should begin with preparatory meetings to review the legislative background, and agreements from previous stages should be reviewed and developed.

- Use modern technology to gather data, document agreements, ensure joint operations are smooth, quick and transparent, establish joint information units between the two sides to address terrorism, smuggling and other activities, and establish a hierarchy of authorities at each security level.

- Examine the previous agreements on patrol routes and observation towers to develop them into long-term arrangements.

- Activate the previous agreement on establishing a professional Yemeni border guard, specifying its size, criteria for personnel selection, funding and training. Reestablish coordination with the United States and Oman.

- Establish rules for grazing areas on each side of the border, based on the 2000 treaty and how Yemen and Oman have managed this issue. Use the same approach to the maritime border – which is governed by the 2000 treaty – to prevent smuggling and delineate fishing areas.

- Begin training staff to manage the land crossings between the two countries, paying attention to potential disparities in the salaries of Saudi and Yemeni employees to help reduce the chances of corruption.

- Rehabilitate staff of the specialized agencies through awareness courses on the laws, the importance of professional conduct, and the items of the border agreement relating to each entity (customs, quality control, health, etc.).

3 – On Economic Development:

- Review the legislation governing trade and economic cooperation in the border agreements, making use of local and international experts to revive the committees responsible for organizing border authorities.

- Plan to set up free zones, identify the most suitable locations and set regulations that allow the residents of these areas to benefit, and build warehouses to store merchandise including foodstuffs.

- Study the establishment of joint markets on both sides of the border to enable residents to trade crops and livestock with each other on specific days of the week, under the supervision of a joint committee.

- Specify the agricultural, animal and industrial goods that can be granted special status by either country for import or export from traders in the other country, while ensuring this status is regularly updated.

- Put in place a mechanism to manage water resources within the areas specified for joint pasture and draft an agreement on fishing rights.

4 – On Property Rights:

- Update the survey of private property on both sides of the border through the private property committee.

- Create a joint mechanism to enable Yemenis to litigate in Saudi courts over property now under Saudi control on the northern border and Saudis to litigate over private property inside Yemeni territory.

To the United States and Oman:

- – Work with Yemen and Saudi Arabia to arm and train Yemeni border guards, seeking guarantees that aid is used only for specified uses.

- – The United States should provide technical cooperation to each country to develop monitoring mechanisms on both sides of the border. Oman should deploy its expertise in border issues to help train border personnel.

- – During the first stage of the military and security committees’ work, experts from the United States and Oman should be included as observers until trust is built up between the two sides. This would help Yemen and Saudi Arabia work in other areas without the need of a third party.

- “Saudi claims victory in war with Yemen’s Houthis,” Al Arabiya News, December 26, 2009, https://english.alarabiya.net/articles/2009/12/26/95367

- “Saudi Arabia builds giant Yemen border fence,” BBC News, April 9, 2013, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-22086231

- Ahmed Nagi, “Yemeni Border Markets: From Economic Incubator to Military Frontline,” Carnegie Middle East Center, June 14, 2021, https://carnegie-mec.org/2021/06/14/yemeni-border-markets-from-economic-incubator-to-military-frontline-pub-84752

- Muhammad Hasan al-Aidarous, Arab-Arab Borders in the Arabian Peninsula [AR] (Cairo: Dar al-Kitab al-Hadith, 2002, 1st ed.), p. 257.

- Ali Nasser Muhammad, “The Memory of a Nation: The People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen from 1967 to 1990 [AR],” (Baghdad: Dar al-Mada, 2020), p. 150.

- Hasan Abu Taleb, “The State of Yemeni Borders with Oman and Saudi Arabia [AR],” Al-Siyassa Al-Dawliya, January 1993 (111 ed.), p. 220.

- Ibid.

- “Memorandum of Understanding Between the Government of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Government of the Republic of Yemen [AR],” February 26, 1995, Article 5. Document obtained by the authors.

- It was headed by Sheikh Abdullah bin Hussein al-Ahmar on the Yemeni side and Prince Sultan bin Abdulaziz on the Saudi side.

- “Memorandum of Understanding Between the Government of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Government of the Republic of Yemen [AR],” February 26, 1995, Article 5.

- Information obtained from minutes of the committee meetings, copies of which were reviewed by the authors.

- The committees at the second and third levels were formed between January and June of 1996, according to the joint report on completion of the handover for implementation of the border agreement by the joint Yemeni-Saudi military committee on June 5, 1996.

- Information obtained from minutes of the committee meetings, copies of which were reviewed by the authors.

- Based on the text of the Yemeni-Saudi Border Agreement, 2000, Article 4.

- Full text of the International Boundary Treaty Between the Republic of Yemen and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, United Nations Peacemaker database, https://peacemaker.un.org/saudiarabiayemen-bordertreaty2000; See also, a US-government map based on the boundaries laid out in the agreement: “Guidance Bulletin, No. 21, Saudi Arabia/Yemen Boundary,” US Department of State, Office of the Geographer, February 5, 2001, https://hiu.state.gov/cartographic_guidance_bulletins/21-Saudi-Arabia-Yemen-2001.pdf

- Implementation was overseen by a committee formed according to the Treaty of Jeddah, signed June 12, 2000, https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/SA YE_000612_International Border Treaty between the Republic of Yemen and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.pdf

- Draft agreement to regulate border authorities between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Republic of Yemen, May 16, 2001.

- The draft was a result of the meeting of representatives of the security agencies of the United States, the Sultanate of Oman, Saudi Arabia and Yemen at a US military base in Germany in 2007.

- Minutes of the meetings of the joint Yemeni-Saudi field team, April 4-6, 2004, as well as the joint committee approving the working plan for the towers and patrol routes on March 8, 2004.

- Draft agreement to regulate border authorities between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Republic of Yemen, May 16, 2001, Article 3.

- Draft agreement to regulate border authorities between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Republic of Yemen, May 16, 2001, Article 6.

- The committee regulating border authorities based its work on a security agreement made in July 1996.

- Ibid., Articles 6 to 10.

- Ibid.

- Yemeni border personnel have traditionally been under the authority of tribal leaders in the border areas, through whom they receive their salaries; sometimes they are ghost soldiers on the payroll.

- Minutes of the seventh meeting of the ministers of interior of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Republic of Yemen on June 8-9, 2003, paragraph 1.

- Draft agreement to regulate border authorities between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Republic of Yemen, May 16, 2001, Article 9.

- Draft agreement to regulate border authorities between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Republic of Yemen, May 16, 2001, Article 6.

- Minutes of the sixth meeting of the joint Yemeni-Saudi committee to implement paragraph A of Article 2 of the Yemeni-Saudi border agreement, conducted on June 2, 2004 and resulting in the formation of the “Committee to Survey Private Property in the Border Areas”. The committee surveyed private property over the period of a year.

- Aziz El Yaakoubi, “Saudis seek buffer zone with Yemen in return for ceasefire – sources,” Reuters, November 17, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/yemen-security-saudi-usa-int-idUSKBN27X20B

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية