Ever since the internationally recognized government fled from Sana’a after the Houthi takeover in 2014, it has failed to develop a strategy to adapt to its new environment and the challenges it poses. Instead, it has continued to act as if nothing has happened, and only a few tweaks are required to keep going. This can be seen clearly in the decision to maintain large cabinets, along with hundreds of deputy ministers added to accommodate the relatives of powerful government figures. Whenever conditions deteriorated, the miracle cure would be a cabinet reshuffle drawing from the same pool of corrupt officials. Each new prime minister presented a government program that they knew, and everyone else knew, could not be implemented.

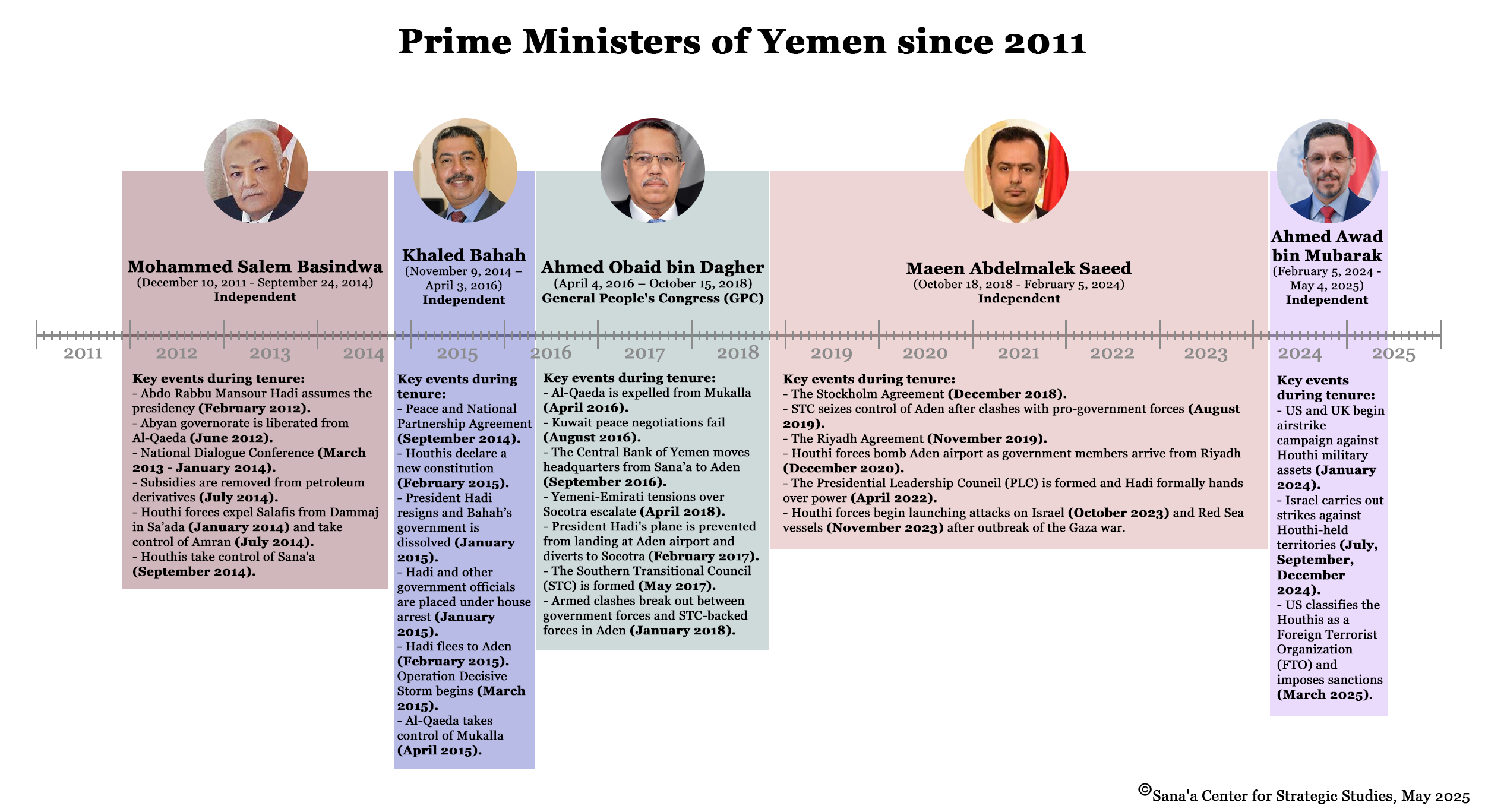

So when Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak replaced Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed in February 2024 as prime minister, the public did not expect a major improvement in their living conditions. They had seen cabinet reshuffles before, accompanied by grand promises and ambitious reform plans, but things kept getting worse. With the exception of improved security in Aden, the interim capital, nearly all aspects of life continued to deteriorate.

On the economic front, the performance of Bin Mubarak’s government was marked by three critical deficiencies: unprecedented electricity blackouts; the collapse of the Yemeni rial; and the inconsistent payment of public sector salaries. His tenure saw shrinking fiscal revenues, reduced financial support from Saudi Arabia, and political infighting, rendering the installation of any cohesive policy or effective governance impossible. Bin Mubarak had his own grandiose plan, the “Five Tracks of Reform.” The fact that he identified different tracks on separate occasions did not inspire confidence among the public.

A quick look at the lack of accomplishments of Bin Mubarak’s cabinet reveals a failure as dismal as those that came before it. His government formulated a two-year Economic Recovery Plan for 2025-2026, supplemented with a policy matrix outlining implementation responsibilities and measurable benchmarks. However, the plan lacked any realistic assessment of the deeply entrenched political and economic divisions within government-controlled areas. Its limited temporal scope suggests its extensive list of objectives is ludicrously unrealistic, especially given the absence of a mechanism for funding.

Bin Mubarak rose to public prominence in 2011, soon becoming part of President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi’s inner circle. He wore many hats during the National Dialogue Conference (2013-14) while concurrently serving as the Director of the President’s Office. He continued to build influence, particularly with regard to high-level appointments, after he became Yemen’s ambassador to the US in 2015, then added the post of Yemen’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations to his portfolio. Notably, upon becoming foreign minister in 2020, he sought to retain his US ambassadorship, a demand that drew widespread public criticism.

Bin Mubarak’s turbulent and brief term as prime minister was characterized by fights over power with the Presidential Leadership Council (PLC), among members of the PLC, and within the cabinet itself. The council members who represented political or armed factions of the government refused to abide by the prime minister’s instructions, as the PLC had not codified its bylaws. Ministers frequently demanded Bin Mubarak’s removal, escalating into a boycott of government meetings that paralyzed the cabinet for months. Only 16 regular cabinet meetings were held during Bin Mubarak’s entire tenure. The constitutional stipulation that all executive competencies are assigned to the cabinet, which has been ignored since the 1970s, is now completely forgotten.

Tensions finally came to a head in early May, as Bin Mubarak resigned and PLC head Rashad al-Alimi named Finance Minister Salem bin Briek to take his place. The appointment of Salem Bin Breik, a Hadrami, comes amidst an increasingly complex political and economic landscape, particularly within Hadramawt itself, where local tribal and political organizations are increasingly pushing for self-governance. His appointment could be a symbolic gesture to quash Hadrami discontent and promote an illusion of political inclusivity in the executive. Bin Breik also enjoys unified support from members of the PLC. During his tenure as finance minister, Bin Breik cultivated cordial relationships with various factions, including the Southern Transitional Council (STC). While this could smooth ties between the cabinet and the PLC, it could also undermine governmental effectiveness, should PLC members use Bin Breik’s acquiescence to consolidate control over decision-making, prioritizing their self-serving agendas over the interests of the suffering populace.

Prior to his recent appointment as prime minister, Bin Breik had over a decade of experience in public finance, holding key positions in the Finance Ministry and its Customs Authority. He worked as the director of customs in the ports of Hudaydah, Mukalla, and Aden, and at the Al-Tuwal border crossing, culminating in his appointment as head of the Customs Authority in 2014. This was a calculated maneuver by then-Finance Minister Mohammed Zemam, who installed Bin Breik as a pliable figurehead to continue his own stranglehold over the ministry’s most lucrative revenue stream, according to a source in the Customs Authority. However, Bin Breik continued his rise in the ministry and was appointed Deputy Finance Minister in 2018 before assuming the top job in 2019.

In contrast with some of his peers, Bin Breik’s tenure as finance minister was notable for the absence of overt personal corruption. However, under his leadership, the ministry failed to improve resource mobilization, managing to collect a mere 30 percent of legally owed revenue. This can be attributed to rampant corruption within tax and customs agencies, a feeble revenue collection scheme, and a lack of competency in the workforce.

Despite his relatively good relations with members of the PLC, Bin Breik has repeatedly clashed with the leadership of the central bank over the allocation of shrinking resources. According to a senior government official, Bin Breik reportedly requested the dismissal of Central Bank Governor Ahmed Ghaleb al-Maabqi, a widely respected technocrat, as a condition of accepting the premiership. Al-Maabqi had fought against the government’s policy of printing new currency to finance its widening fiscal deficit, which has since resulted in rampant inflation. Bin Breik will inherit other monetary and fiscal challenges as well, including the refusal of several government factions to deposit revenues into central bank accounts. This could be a litmus test for Bin Breik and his ability to redress the profound imbalances within the government fiscal system.

The current atmosphere of corruption, ineffectiveness, and graft exists not only because of the caliber of politicians now in government, but is an inevitable result of structural shortcomings. State institutions have long been weak, but there were basic instruments to fight corruption when the political will existed to do so, such as the Central Organization for Control and Audit, the Anticorruption Committee, the Public Funds Courts, and parliamentary oversight. Since the government moved to Aden, it has developed some state institutions, but not those involved in oversight. Perhaps unsurprisingly, government stakeholders have not volunteered to limit the discretionary power they enjoy and profit from.

There are other causes of government ineffectiveness and corruption. The internationally recognized government continues to operate, for the most part, in exile. Ministers spend most of their time abroad; some still have their main offices in Riyadh. The government’s reliance on Saudi funding and hospitality is a major factor complicating its effectiveness. Not only is this intrusive and corruptive, but it also undermines efforts to improve oversight, cooperation, and accountability. Political elites maintain their own links to foreign sponsors, allowing them to defy domestic rule.

Another layer of complication is the STC’s aspiration to restore an independent southern state. Senior STC officials have hinted privately that they are not keen on the success of the government, as material progress might limit popular support for secession. STC head Aidarous al-Zubaidi demonstrated this view when he stated during a 2021 interview that the fall of Marib (and the defeat of the government) would inevitably lead to negotiations between the North and the South, with the STC controlling most of the latter and Houthis controlling most of the former.

Changing the captain of a broken ship is not the answer to the Yemeni government’s intractable woes. Rather, the best solution is to formalize a clear legal delineation of the mandates of the cabinet vis-a-vis the PLC. Collective leadership representing a fragmented political elite, as it exists now, cannot effectively run the executive. That is why the North Yemen constitution of 1971 and the Unity Constitution of 1991 assigned executive power to a non-partisan cabinet. Such an arrangement would give the government a better chance of tackling the major challenges facing it on multiple fronts.

This commentary is part of a series of publications produced by the Sana’a Center and funded by the government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The series explores issues within economic, political, and environmental themes, aiming to inform discussion and policymaking related to Yemen that foster sustainable peace. Any views expressed within should not be construed as representing the Sana’a Center or the Dutch government.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية