Executive Summary

Since April 2022, the war in Yemen has mutated from a high-casualty conflict to a protracted stalemate with relatively stable frontlines. The contest is now over the economy, as the Houthi group (Ansar Allah) leverages negotiations and its military power to put fiscal pressure on the internationally recognized government. The current phase has been marked by the expansion of economic warfare, with the Houthi authorities shutting down trade from government-controlled areas, stoking discontent as public utilities break down and the currency tumbles.

- The Houthi attack on government revenue streams began last fall with a blockade of oil exports and has expanded into competition for customs revenues and a ban on cooking gas produced in government-held areas.

- The precipitous decline in oil, gas, and tax revenue has resulted in massive budget deficits and reduced the government’s capacity to cover essential expenditures, including the payment of public sector salaries and the provision of electricity.

- The expiration of a Saudi fuel grant has precipitated an electricity crisis in the south, with the government and private operators unable to run power plants. By September, residents in the interim capital of Aden received as few as four hours of power each day.

- The August 2023 announcement of a new US$1.2 billion grant from Saudi Arabia will provide a measure of relief, but the vast public sector cannot subsist on irregular handouts, and private investment is limited by conflict and political fragmentation.

- Without substantial and sustained financial assistance, the economic and humanitarian situation in Yemen will rapidly deteriorate.

- Hundreds of thousands of employees working in the government-controlled public sector and their dependents will lose their primary source of income if salaries go unpaid, and their purchasing power will fall with the devaluing rial as the central bank’s foreign currency reserves dry up.

This paper details the circumstances of the destruction of the public revenue streams of the internationally recognized government and identifies potential avenues for their restoration. It was informed by the research of the Sana’a Center Economic Unit and consultations and discussions at the 9th Development Champions Forum (DCF), held from May 24-26 in Amman, Jordan, as part of the Rethinking Yemen’s Economy Initiative. [1] Participants discussed and debated potential avenues for relief of the government’s fiscal crisis and suggested streams of exploitable revenue for further study of their viability.

- Raising or improving the collection of income, commercial, or even point-of-sale taxes in Yemen is currently beyond the government’s ability to enforce, due to its limited wartime capacity and geographic fragmentation.

- Calibrating the realities of the current political situation, a number of suggestions were proposed for the exploitation of public assets and utilities that the government may wish to consider.

- Crude oil might be sold on restructured futures contracts, or dealt to private regional exporters, through a transparent process. Customs and tax collection could be streamlined or decentralized.

- Also, the government should explore optimal models for creating effective partnerships with the private sector and encourage it to provide electricity distribution services, as well as studying the possibility of privatizing the electricity sector, even partially, or financing and rationalizing it through a pre-payment system to address the woeful collection of utility bills.

- Other assets, including the publicly owned telecommunications company, could be reformed, as could expenditures, including the security and public sectors.

- Deeper reforms are dependent on strong and effective state institutions, which have long been absent from Yemen and whose reconstitution likely awaits the conclusion of the war. Additional support for the machinery of state could have a multiplier effect in alleviating the longer-term crisis, but would take time to have an effect.

The measures outlined here will not rapidly reverse the government’s financial fortunes on their own, but could mitigate its current predicament and restore a measure of faith in its ability to govern. Ultimately, Yemen requires two developments: an economic truce to decouple its stalled military competition from the livelihoods and well-being of its civilian population, who are being pushed further into poverty and desperation; and sustained financial support from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, that it may engage in the long-term rationalization of revenues and expenditures and underwrite much-needed reforms.

Introduction

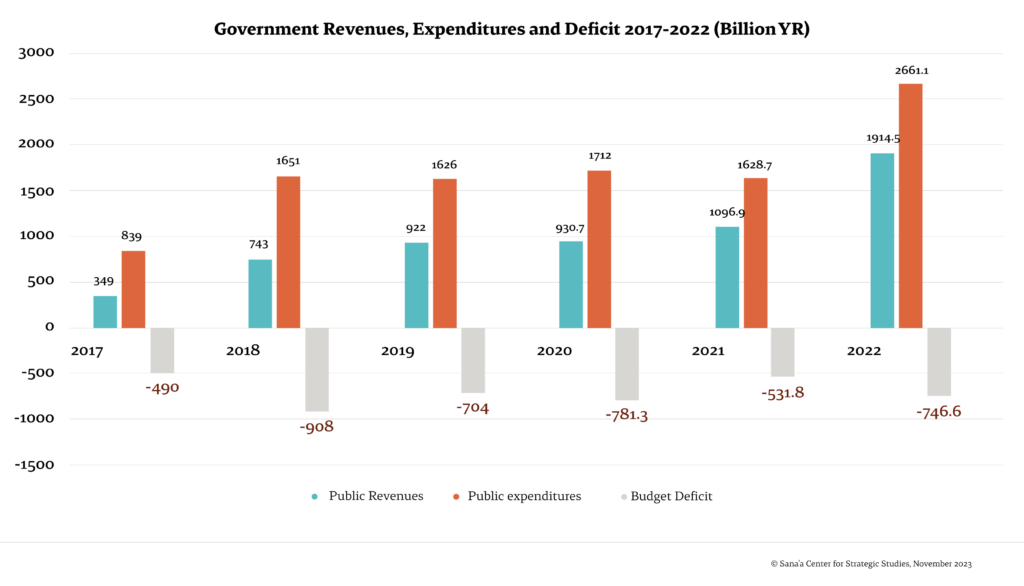

The internationally recognized Yemeni government was on the verge of financial collapse before the August 1, 2023 , announcement of a US$1.2 billion Saudi grant.[2] Public revenues have been decimated as the Houthis shut down streams of funding, and there are few options for their renewal. This has been compounded by divisions within the government, leading to dysfunction, depleted capacities , and allegations of corruption, which have hindered the collection of taxes and other local revenues and precluded the rehabilitation of its finances through higher taxation or improved collection.

With the enormous and continuing costs of the conflict, a failure to rehabilitate the government’s revenues will remove its ability to pay military forces and public sector salaries. Absent sustainable sources of funding, a protracted flirtation with bankruptcy would undermine it s already fragile claims of legitimacy. The effects of the fiscal crisis have been tangible and immediate: Unable to afford fuel, the government cannot keep the lights on, and rolling blackouts across southern Yemen during the hottest months of the year have stoked public anger and popular demonstrations.

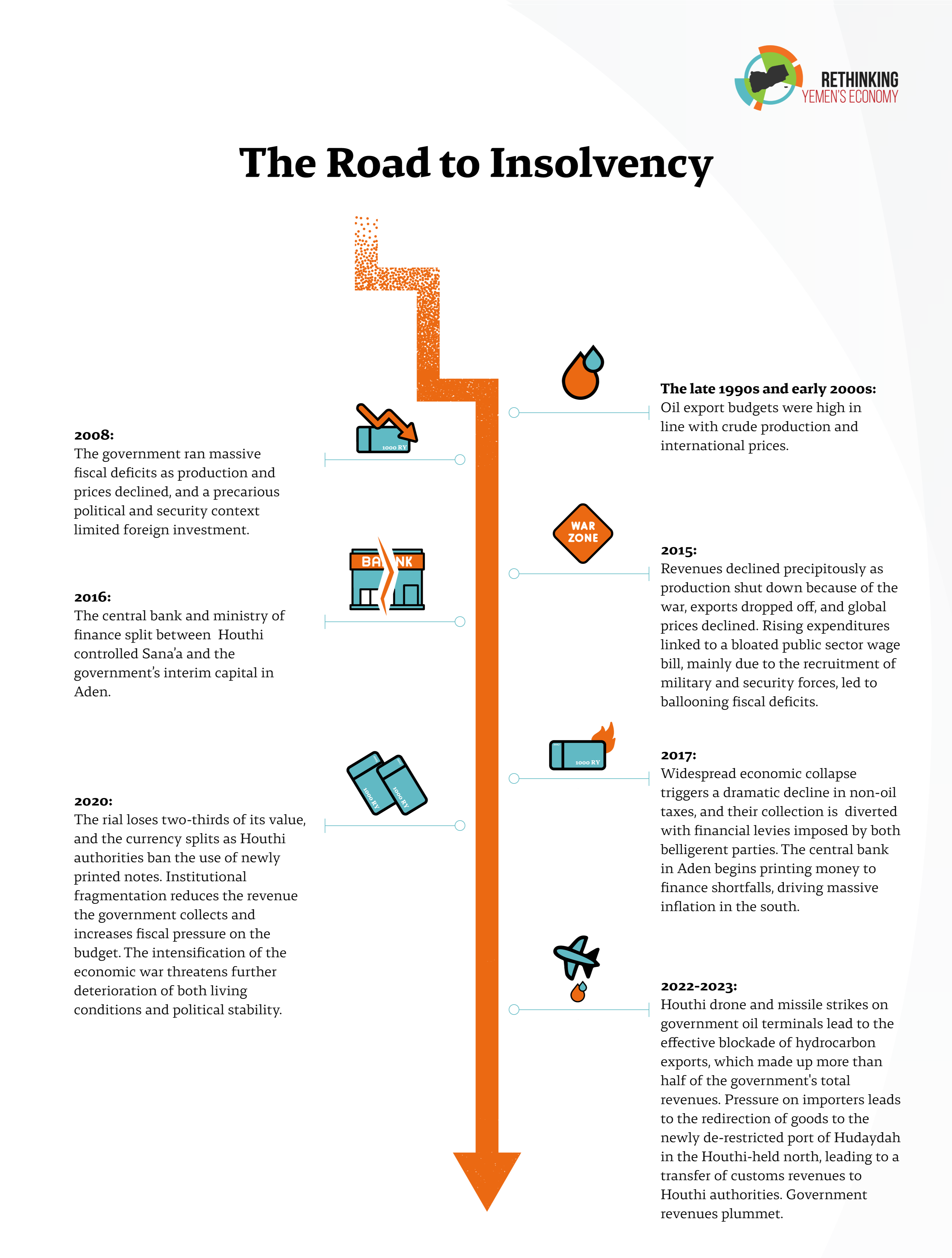

The underlying problems are not new : A vast government payroll, high fuel subsidies, and an over-reliance on hydrocarbon revenues have placed an enormous burden on state finance and survived repeated attempts at reform. Oil exports kept budgets afloat in the late 1990s and early 2000s when crude oil production and international prices were high, but from 2008, Yemen began to run huge fiscal deficits as both output and prices declined.[3] A precarious political and security context limited foreign investment and concentrated government debt in domestic instruments.

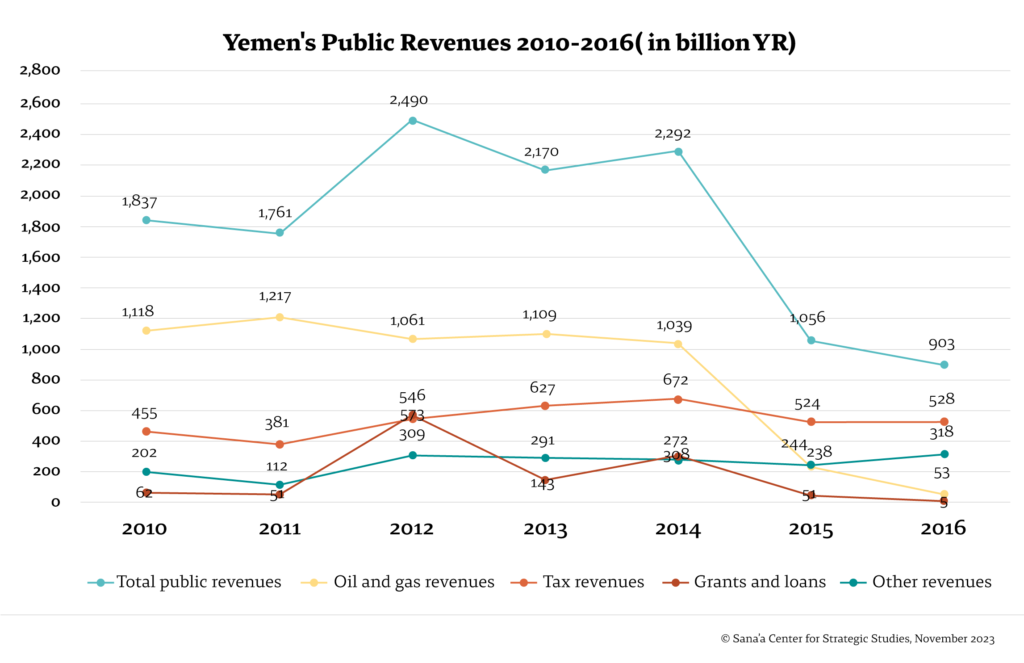

In 2009, the deficit rose 134 percent, to 502 billion Yemeni rials (YR) from YR215 billion, due to the sharp decline in oil prices. O il and gas exports as a share of public revenue fell, [4] but continued to dominate the budget revenue structure , accounting for 55 percent of total government revenues from 2010-2014.[5] By comparison, revenues from taxes and from grants and foreign aid accounted for 26 and 8 percent of total government revenues respectively.[6] Over this period, current expenditures represented more than 85 percent of total public expenditures, with only 13 percent allocated to finance capital investment projects.[7] P ublic sector salaries accounted for about one-third of government spending.[8] With the outbreak of conflict in 2015, revenue declined precipitously as oil production shut down, exports dropped off, and global prices fell.[9] P ublic expenditures went down with it, declining 36 percent between 2014 and 2016.[10] The widespread economic collapse also triggered a dramatic decline in non-oil taxes, and their collection has been diverted with financial levies imposed by the warring parties since 2017. A bloated public sector wage bill, mainly due to the recruitment of new military and security forces, led to ballooning fiscal deficits.[11] Foreign grants and loans were frozen, and banks stopped purchasing public debt.[12] By 2015, the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) was financing 84 percent of the budget deficit,[13] and total debt reached 94.4 percent of GDP.[14]

In 2017, the government-aligned Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden) began a massive expansion of its overdraft to the government by printing and issuing new money , driving massive inflation. By 2020, the rial had lost two-thirds of its value. The bifurcation of the central bank and ministry of finance in 2016 was followed by the split of the currency in 2020, as Houthi authorities prohibited the use of the newly printed notes.[15] The institutional fragmentation of tax and budgetary authorities reduced the amount of revenue the government could collect and increased fiscal pressure on the budget.

Yemen’s frontlines have remained largely unchanged since the brokering of a UN-sanctioned truce in April 2022. Its expiration that October has not heralded a return to full-scale fighting, but Houthi authorities have kept up pressure on the internationally recognized government by shifting their focus to the economic sphere. Less than three weeks after the truce expired, Houthi drones targeted two oil terminals on Yemen’s southern coast.[16] More attacks followed in subsequent weeks. The result has been the complete shutdown of hydrocarbon exports, erasing the government’s primary source of revenue and one of its only sources of hard currency.

But the drone strikes were only the first salvo in a campaign to isolate and bankrupt the government. The coalition had heavily restricted trade to the major port of Hudaydah earlier in the war, and the Houthis now looked to turn the tables. Leveraging ongoing negotiations with Saudi Arabia, Houthi authorities secured an agreement t0 lift restrictions imposed on commercial shipments entering Hudaydah’s ports. They then promptly weaponized this concession by blocking overland imports from Aden and forcing traders to redirect them through Houthi-controlled ports. On August 6, they announced additional tax hikes on all goods and imports brought overland from government-controlled areas.

The result is a transfer of desperately needed customs revenue from the government to Houthi authorities, losses the head of the CBY-Aden estimated could reach YR50 billion (approximately US$40.2 million) per month.[17] The move has been compounded by further restrictions on trade from government-held territory. Domestically supplied cooking gas, produced at the Safer facility in Marib, had been sold nationwide, even during intense fighting. Houthi authorities banned its import into the populous north in May 2023, shutting down another stream of government revenue.

The government faces substantial challenges in mitigating the crisis. Its revenues have been supplemented by conditional financial support from the Saudi and Emirati governments, which pledged US$2 billion in 2022. The injection of hard currency initially helped stabilize the value of the rial and financed the import of basic commodities, such as food, on which the country is nearly completely dependent. Further support came in the form of Saudi grants of diesel and mazut[18] to supply Yemen’s power stations.[19] But the money did not last long, and the fuel grant expired in April 2023.[20] The rial promptly dropped to levels not seen since Houthi forces were at the gates of Marib in late 2021,[21] and power stations began shutting down in Aden, as the government could no longer afford to supply them with fuel. Belated support arrived in August 2023, when the first tranche (amounting to US$267 million) of a new Saudi grant worth US$1.2 billion was released, but absent massive, sustained support, or the rapid restoration of revenue streams, the government will face repeated bouts of unrest and a crisis of legitimacy. Apart from external aid or a political settlement, opportunities are limited. The intensification of the economic war threatens further deterioration of both living conditions and political stability. Without sustained assistance, it threatens disaster.

Public Revenues

Oil and Gas

Oil is Yemen’s most lucrative export commodity, which has ensured the historical politicization and contestation of associated export revenues. The current conflict is no different. Yemen’s oil and gas fields remain primarily in government-held territory, as do production and export facilities. Export revenues were the primary source of government revenue before the conflict and, after shutting down at its outset in April 2015, resumed their place as its primary stream of funding.[22] Prior to the conflict, oil and gas rents accounted for 83.3 percent of total merchandise exports, 24.1 percent of the gross domestic product, nearly 50 percent of foreign exchange reserves, and 50-60 percent of the country’s public budget financing.[23]

The eruption of the conflict in early 2015 caused an almost complete halt of oil and gas exports, and associated revenues were down 95 percent in 2016 compared to 2014.[24] But in the summer of 2016 the government resumed limited crude oil exports from the Masila basin under state-owned operator PetroMasila, and production witnessed a gradual recovery with the return of foreign oil companies OMV and Calvalley in 2018 and 2019.[25] Prior to the Houthi attacks on oil export facilities, the government was exporting around 50 thousand barrels per day on average, 57 percent of which came from the Masila basin, with the rest exported from the Marib-Shabwa basin.[26]

Driven by higher global prices, the value of oil exports rose 53 percent from 2020-2021, to YR 398 billion, comprising 36 percent of total public revenue and 2 percent of GDP, according to the government-affiliated Central Bank of Yemen in Aden.[27] A massive Houthi offensive to seize the lucrative oil fields around Marib, which would have underwritten the future of the envisioned Houthi state, stalled in the winter of 2021 after the intercession of Emirati-backed forces, and government exports continued. According to the government-affiliated Central Bank of Yemen in Aden, oil revenues for the first half of 2022 increased 34 percent over the same period in 2021, from US$551.7 million to US$739.3 million.[28] Oil revenues recorded in the 2022 public budget amounted to YR1.107 trillion (approximately US$904 million), constituting approximately 57.9 percent of total public revenue.[29]

The brokering of a UN-sanctioned truce in April 2022, and its subsequent extensions, instilled hope for a broader economic recovery as frontline fighting died down. But the truce expired in October 2022 amid acrimonious negotiations between the government and Houthi delegations. Disagreements centered on the reopening of roads, particularly around the frontline city of Taiz, and ultimately foundered after an eleventh-hour demand by Houthi negotiators that the government use oil and gas revenues to pay public sector salaries – including those of Houthi military and security personnel – a provision they have continued to push for.

The Houthis have repeatedly condemned hydrocarbon exports as squandering a national resource, and threatened consequences for its continuation. Unable to take the oil fields by force, and failing to negotiate the capture of their revenue, they promptly endeavored to shut them down. On October 18 and 19, Houthi drones targeted the Al-Nushayma oil terminal in Shabwa, where the Tanzanian-flagged oil tanker Hana was docked.[30] On October 21, two Houthi drones crashed into the Al-Dhabba oil port in Al-Shihr district in Hadramawt as the Nissos Kea, a Greek tanker, was preparing to load oil.[31] While the government reported no casualties or damage, the Kea departed without taking on its intended cargo of 2 million barrels of oil. On October 25, local authorities closed the port of Mukalla after detecting Houthi drones. On November 21, the government reported another drone attack at Al-Dhabba.[32] Exports were halted as shipping companies and their insurers balked at the prospect of operating under fire. The government’s primary source of funds vanished : the World Bank now estimates a 40 percent decrease in total annual revenues for 2023.[33]

There are limited opportunities for the revival of hydrocarbon exports. Expanding local refining capacity to cover domestic fuel demand is not a feasible option, as it would require both enormous investment and a safer operating environment. Ongoing Saudi negotiations with the Houthis would seem the most likely avenue for securing a deal for safe transit. The Houthis have voiced interest in using hydrocarbon revenues for public sector salary payments, whose provision remains a pressing and potentially destabilizing issue in both zones of control. The current suspension of exports has shut down most production, but it is reasonable to expect that at some point in the future exports will be allowed to resume. The government could mobilize additional revenues by taking concrete actions to implement a decree it issued in January to raise the price of locally refined petrol by almost 180 percent, from YR175 to YR487.5 per liter. Continuing to sell fuel at highly subsidized prices has deprived the government of close to YR200 billion annually, as it is sold at less than 19 percent of the prevailing liberalized price in government-controlled local fuel markets.[34] But subsidies are often entrenched through corruption dynamics, and the ability of the impoverished population to absorb price hikes requires significant further study.

In addition, the opening of the ports of Hudaydah to commercial goods has enabled Houthi authorities to end their reliance on government-produced commodities. Despite the conflict, some industries remained nationally integrated. Cooking gas was domestically produced at the Safer facility in Marib, and had continued to be internally exported to Houthi-held areas even during the height of the fighting. Now able to import gas through Hudaydah, the Houthis banned the transport and sale of domestically produced gas in May 2023.[35]The current output is substantial: Roughly 165,000 cylinders are sold each day, at a price of YR2,100. Monthly revenue from cooking gas amounts to some YR10.4 billion. As of January, the government has proposed increasing the price of a cylinder to YR3,000, and the Presidential Leadership Council has issued a decree in support of the measure, which has gone unheeded by authorities in Marib. Enforcement of the price hike could generate up to YR5 billion a month in additional revenue.

Lastly, it is worth mentioning the shuttered Balhaf LNG facility, Yemen’s largest-ever investment project.. In 2014, LNG revenues recorded in the public budget a mounted to YR158.3 billion (equivalent to about US$740 million).[36] However, production at the facility has been halted since the outset of the conflict. But the significant increase in the price of liquified natural gas on international markets following the Russian invasion of Ukraine has inflated the opportunity cost of its dormancy. Its output would now net the government at least US$2 billion a year.[37] The resumption of liquified gas exports could likely only come as part of a wider political settlement or security agreement,[38] but might be readied for operation should the opportunity arise.

Customs and Taxes

In negotiations with the Saudi government, Houthi authorities secured the removal of coalition import restrictions on the ports of Hudaydah and the expedition of UN monitoring.[39] With commercial goods now allowed to enter the port, the Houthis moved to shut down the overland transport of commodities imported through the government-held port of Aden. In addition to offering lower import duties, the Houthis halted trucks heading north into their zone of control, and threatened traders that they would no longer be allowed to operate there if they continued to import goods through the south.[40] In August 2023, they put in place prohibitive customs fees on overland trade, again pushing merchants to reroute their goods. The result has been the indirect transfer to Houthi authorities of up to YR50 billion per month in customs duties.[41]

The move was well- timed by Houthi authorities – lifting the restrictions on the port of Hudaydah came amidst a controversial and ultimately abortive attempt by the government to raise its own revenues through higher customs duties. In January, the government introduced a package of economic reforms, including increasing the customs tariff on imported goods by 50 percent, from YR500 to YR750 per US$1 in areas under its control, in an attempt to account for the devaluation of the rial. The government Customs Authority reported that customs revenues had already increased by 99.65 percent to YR571 billion in 2021 compared to 2020,[42] following a July 2021 rise in the customs exchange rate from YR250 to YR500 rials per US$1. According to the government-affiliated Central Bank of Yemen in Aden, tax and customs revenues increased by 36 percent during the period 2021-2022, reaching YR790 billion, which constituted 41 percent of total public revenues. But once the monopoly on imports was removed, the proposed hike made government ports less appealing to traders. Data from the Assessment Capacities Project (ACAPS) Yemen Economic Tracking Initiative shows a significant decline in imports through the port of Aden [43] from 47.8 percent to 22.7 percent of Yemen’s overall imports.

Tax and customs revenues are an important source of national income : in 2022, they accounted for about 30 percent of the government’s revenues, compared to 58 percent for oil.[44] But due to poor tax compliance, even prior to the conflict, Yemen suffers from one of the lowest tax collection rates in the world. The average tax revenue collected for the period 2008-2013 amounted to only 6.68 percent of GDP, compared to near 15 percent in countries with similar economies, such as Egypt and Jordan.[45] Corruption and mismanagement led to the loss of some US$4.7 billion in uncollected taxes; there were only 3,080 registered taxpayers as of 2013, from a population of 25 million.[46]

Tax evasion occurs in many forms. Most businessmen either report lower profits than they actually mak e and then pay less in taxes, pay bribes to tax collectors in exchange for reducing their taxable income, or circumvent the process altogether. Tax evasion is mostly associated with small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Tax collected from SMEs doesn’t exceed 5 percent of total tax revenue , even though they constitute a large portion of economic activit y and represent 99.6 percent of businesses in Yemen.[47]

These problems have compounded long-standing inefficiencies in the collection of customs duties and other taxes, including various levels of corruption. The rampant corruption in public units operating under the organizational structure of the government-affiliated Tax Authority motivates taxpayers toward non-compliance and deprives the government of substantial income. There is also high fiscal leakage in the collection of custom tariffs. Only 30 to 40 percent of government-due customs taxes are collected, while the remaining portion is diverted by corruption, inefficient systems for monitoring collection , and a shortage of well-equipped staff at customs clearance centers.[48]

The circumstances of the conflict and the non-payment of public sector salaries have exacerbated these issues. Military and security personnel have set up their own checkpoints and imposed illegal tolls as a supplementary source of income.[49] The government’s limited capacity and administrative reach, along with the more pressing needs of the conflict, have curtailed momentum for rehabilitation.

Public Utilities

Electricity

Southern Yemen is in the midst of an electricity crisis, with the government no longer able to afford fuel for its power plants. The Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program for Yemen (SDRPY) provided a fuel grant in November 2022, which supplied over 1.2 million metric tons of diesel and mazut, valued at US$422 million, for power generation at more than 80 stations. The government is estimated to pay some US$100 million per month for additional fuel.[50]

The expiration of the grant in April and the government’s limited capacity to make up the difference led to ever-longer blackouts, particularly as demand spiked during the hot summer months. Residents of the interim capital Aden are currently receiving as few as four hours of electricity per day. Authorities in Aden briefly threatened to withhold revenues from the central government and reserve them for local use.[51] Protests and demonstrations have broken out in southern governorates as the shortages and heat intensify.

Newly announced Saudi funding may promise some respite, but Yemen’s electricity provision is notoriously poorly managed, reliant on massive subsidies, and suffers from the limited collection of utility payments.[52] The SDRPY reported that the payment of electricity bills accounted for only 7 percent of the total spent through the Saudi oil derivatives grant during the period May-July of 2021.[53] The average retail price of a kilowatt-hour is subsidized to a price of YR7 to households in government-held areas, some 3 percent of what it costs in Houthi-controlled territory, where the Public Electricity Corporation is currently pricing a kilowatt-hour at YR238. There has also been widespread looting of fuel derivatives from power stations.

Electricity subsidies likely underpin extreme inefficiencies and widespread corruption, but they are also one of largest de facto social support policies in government areas. Their provision is probably better conceptualized as an expense that could be mitigated rather than a revenue stream, and reform would be difficult due to entrenched local interests and limited funds to upgrade and maintain existing infrastructure, but the current system is no longer sustainable.

Telecommunications

Prior to the conflict, the telecommunications and information technology sector in Yemen was second to the hydrocarbon sector as a source of fiscal revenue and foreign currency.[54] Given that the telecommunication sector is centrally managed in Sana’a, the majority of its fiscal receipts (mostly fees and taxes levied from mobile carriers) have been controlled and mobilized by the Houthis. With the outbreak of the conflict, the sector has suffered from massive losses, amounting to an estimated US$4.1 billion, due to the destruction or damage of infrastructure assets, confiscation of equipment at Yemen’s ports, and conflict-related operational constraints that limit the full utilization of internet services.[55] In addition, institutional and policy divisions and financial demands by the authorities in Sana’a and Aden have paralyzed the sector and limited its capacity to operate freely at the national level.

Most telecoms institutions and government-owned enterprises have been duplicated and come under the control of the warring parties. T he Houthis have expanded the telecoms sector and technological capacities in areas under their control to respond to growing demand for mobile and internet services, and maximized tax receipts from the sector during the conflict. But the government’s fragmented political and economic administration has limited its ability to meet existing demand or respond to the growing market for services in areas under its control, which would provide it with additional income. In September 2018, the government opened a new portal for the provision of internet services called Aden Net, using 4G technology. B ut its coverage is limited to Aden and its expansion to other governorates has been relatively slow.[56] Due to poor market planning, limited investment, and monopolistic practices, this has resulted in high prices and a black market for Aden Net modems, which most people canno t afford.

The government could reactivate the international gateway to reroute international calls through companies operating within government areas, which would allow it to collect associated revenues. The government utility is also currently owed some US$300 million by the Saudi Telecommunication Company, and should call for its immediate disbursement. It has recently sold 70 percent of the public operator to an Emirati company despite objections in parliament, citing the need for additional investment in the sector, but the financial ramifications of the deal are as yet unclear.[57]

Public Spending

Government spending can be divided into several broad categories : public sector salaries, goods, services, maintenance and debt payments, loan interest , and capital expenditures. The public sector wage bill is the largest item in the budget, and swallows up a significant portion of public resources. The bloated public sector in Yemen is the cumulative result of several decades of financial and administrative corruption, and includes thousands of ghost workers – employees who do not show up or do not exist – and “double dippers,” who receive multiple salaries from different sources in the sector. This problem worsened during the war, after parties to the conflict added thousands of new recruits to their payrolls. T he Yemeni government integrated tens of thousands of fighters into its military and security services, which led to a widening of the budget deficit.[58] S pending on salaries increased approximately by 48 percent, from YR556 to YR821 billion, between 2017 and 2018, as a result of new employment and the government increasing the salaries of civil service employees by 30 percent in late 2018.[59]

In 2020, the Yemeni government spent YR878 billion on wages and salaries, which represents 51 percent of total public spending in the areas it controls. This figure is approximately equal to what was spent on wages and salaries for all public sector employees in the 2014 budget, before the outbreak of the conflict. In the latest government finance report for the year 2022, non-oil revenues (including tax and customs revenues) amounted to about YR806 billion, which would only cover approximately 94 percent of the salary bill or 30 percent of total public spending.

The government should take steps to rationalize its bloated payroll and the financing of a disorganized and fragmented security sector. Against strong opposition from labor unions, in August 2023 the government began moving to pay the salaries of civil servants and members of the military and security forces through private banks.[60] With new measures to verify the identities of payees , substantial savings might be realized if the plan goes ahead. Civil and military leaders should also be legally obligated to disclose their income and assets. Increased transparency might improve the efficiency of the system and illuminate where cuts could be made.

In addition, the government should take concrete steps to implement cuts in fiscal expenditures in unproductive areas which involve corruption or bloated budgetary allocations. This is vital for the government to avoid inflationary policies to cover the widening budget deficit, such as again printing new rial banknotes by overdraft from the central bank, deteriorating the value of the currency and destabilizing the economy as a whole.

Recommendations

The current economic crisis is an unprecedented challenge with unpredictable consequences. The rump Yemeni state is already beleaguered by infighting and uncertainty, and the humanitarian and economic situation remains precarious. The effects of bankruptcy on the government could include the complete breakdown of public service provision and the destruction of the currency, placing vital imports out of reach.

In this context, intermittent relief from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates is welcome but insufficient, prolonging dysfunction and inefficiency by preventing longer-term planning, and forcing the government to lurch, hat-in-hand, from one fiscal crisis to the next. The economic crisis touches every household in Yemen, and deepens instability in an already divided and precarious government. A necessary condition of any reform is the mobilization of sufficient political will for its enactment, and the current fiscal emergency might drive much-needed systemic change. The list of recommendations laid out below is not intended to be exhaustive and all avenues for the restoration of revenues must be considered, and with all possible haste.

Oil and Gas:

- c A resumption of exports would potentially lessen the fiscal pressure on the government budget deficit given that part of associated oil revenues c ould be allocated to cover the public sector wage bill in areas under its control, which accounted for over half of total spending in the period 2017-2021. It would also improve the government’s fiscal capacity to cover other vital spending needs and expand public service provision, including electricity. I t would also reduce government borrowing from the central bank and avoid the inflationary impacts of adopting expansionary monetary policies.

- To prepare for the eventual resumption of exports, the government should take steps to prevent the deterioration of equipment and infrastructure, encourage investment in the maintenance of existing oil and gas facilities, and upgrade capabilities where possible to facilitate future production. Additional exploration might also be encouraged. Current production and refining capacity could generate sales in the undersupplied domestic market or be utilized for electricity production. Such steps would require private or foreign investment, but have the potential to increase future revenues, provide jobs, and hasten the resumption of exports when a safer environment emerges.

- The government should also carefully investigate alternative avenues of sale. While it had previously produced and sold oil on the spot market, its dire financial situation necessitates the consideration of other arrangements. It should explore whether there is a viable avenue to raise revenue through modified futures contracts – selling the oil and gas in the ground for future shipment. While it would likely have to provide a discount, the proceeds might still be substantial. The government could work on temporary measures, such as selling oil to regional buyers willing to secure its export themselves. This would also need to be discounted, to account for the transferred assumption of risk, but might still provide desperately needed funds. Any futures contracts or deal to sell oil to regional buyers must be undertaken transparently, and the government must be sensitive to potential political opposition to this approach to resource management.

Customs, Taxes, and Oversight:

- The government should t ake concrete measures to improve the collection and administration of tax and tariff revenues. A comprehensive and robust tax compliance framework should be implemented to connect all aspects of the process, from modernized taxpayer registration and tax filing, to management of payment obligations. Further verification should be used to combat corruption and tax evasion.

- Much could be accomplished through increased oversight: The government should evaluate the leaders of revenue collection agencies against clear performance targets and replace ineffective or low-performing officials with competent, well-trained replacements. It must also endeavor to enforce the consistent application of customs and standardize systems across the governorates it controls. Qualified leaders should be appointed to revenue collection agencies, and tax and customs collection should be consolidated wherever possible, and resultant revenues registered and recorded.

- These efforts should be bolstered by enhanced monitoring at ports and border crossings to curtail smuggling and tax avoidance. Customs regulations should be enforced consistently at collection points. Where possible, digital and automated systems should be implemented to minimize human error and misapplication. The government could also better facilitate customs clearance procedures and explore incentives at government-controlled seaports to increase commercial shipments and the traffic of goods to these ports.

- Should government efforts to improve tax and customs collection fail, further study could determine which, if any, services might benefit from decentralized management, and the requisite authority might be quickly transferred by presidential decree.

- The government should also endeavor to strengthen transparency and accountability measures for expenditures. A major challenge to efficiently allocating public funds in Yemen is the scourge of corruption. The government should take steps to rationalize its bloated payroll and the financing of a disorganized and fragmented security sector. It should benefit from its move to pay the salaries of public sector employees through private banks, but steps to reform could include an audit of public services and reducing administrative corruption by instituting biometric registration of all public sector workers. In addition, the government should conduct an assessment to evaluate other spending items in its budget. It should prioritize and rationalize expenditures to ensure that the focus is only on critical necessities during this period of crisis.

Public Utilities (Electricity and Telecommunications):

- The government should explore models for creating effective partnerships between the public and private sectors for the provision of electricity distribution , as well as studying the possibility of privatizing the sector, even partially, or financing and rationalizing it through a prepayment system, which may address the problems collecting utility bills. Upgrades to the grid, installation of renewable energy sources, and electronic pre-payment systems would improve the efficiency and reliability of electricity provision..

- Any liberalization or privatization of public utilities would need to be handled with extreme care. The wartime sale of public utilities might provide an opportunity for even greater corruption and profiteering if not subject to appropriate regulation and oversight, and steps would need to be taken to limit consumers’ exposure to price shocks, which could drive further social unrest. But there are limited options for increasing provision and lowering expenditures. As with other items, the best and most likely source of relief is exogenous support. Substantial international financing may be available for renewable energy projects, of which the government might take advantage. It must also make every diplomatic effort to secure the renewal of the Saudi fuel grant and whatever assistance might be available for the longer-term reform of the sector, that it may one day stand on its own.

- The government should develop policy-grounded plans to address existing challenges facing the telecommunications sector and exploit viable opportunities to unlock its potential. It should allocate the needed investment to develop the necessary telecommunications and technological infrastructure to attract private sector investment.

- The initiative aims to contribute to peacebuilding, conflict prevention, economic stabilization, and sustainable development by building consensus in crucial policy areas. The program engages and promotes Yemeni voices in public discourses on development, economic issues, and post-conflict reconstruction in Yemen, and is implemented by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, the Center for Applied Research in Partnership with the Orient (CARPO), and DeepRoot Consulting. It is funded by the European Union and the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to Yemen. Figures have been sourced by the Sana’a Center Economic Unit from the government’s own statistics, except where otherwise indicated.

- “Saudi Arabia to grant Yemen $1.2 billion in economic aid,” Associated Press, August 1, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/yemen-economy-saudi-arabia-economic-aid-4329a38962c4b67da018eab44e7aef03. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Republic of Yemen Oil rents (% of GDP),” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PETR.RT.ZS?locations=YE. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Annual Report 2015 [AR],” Central Bank of Yemen, December 31, 2015, http://centralbank.gov.ye/App_ Upload/Ann_rep2015AR.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Whither Yemen’s Economy? ,” Ministry of Planning & International Cooperation, Yemen Socio-Economic Update – Issue 30, December, 2017, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-socio-economic-update-issue-30-december-2017-enar. Accessed October 25, 2023.

- “Annual Report 2015 [AR],” Central Bank of Yemen, December 31, 2015. http://centralbank.gov.ye/App_ Upload/Ann_rep2015AR.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- Casey Coombs and Majd Ibrahim, “Recovering Lost Ground in Shabwa’s Oil Sector,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, August 24, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/20682. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Whither Yemen’s Economy?, ” Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, Yemen Socio-Economic Update – Issue 30, December 31, 2017, https:// reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-socio-economic-update-issue-30-december-2017-enar. Accessed October 25, 2023.

- Sana’a Center Economic Unit, “Addressing the Crushing Weight of Yemen’s Public Debt,” Rethinking Yemen’s Economy, Policy Brief No. 12 Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, DeepRoot Consulting and CARPO, July 2022, https://devchampions.org/uploads/publications/files/Rethinking_Yemens_Economy_No12_En-2.pdf, p.23. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- Ibid, p. 22.

- “Annual Report 2015,” Central Bank of Yemen, December 31, 2015, http://centralbank.gov.ye/App_ Upload/Ann_rep2015AR.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- “Public Debt in Yemen ‘Debt Restructuring or Default’,” Ministry of Planning & International Cooperation, Yemen Socio-Economic Update – Issue 15, June 2016, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/YSEU15_ِEnglish_v6.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- Anthony Biswell, “The War for Monetary Control Enters a Dangerous New Phase,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, January 21, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/8674. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- Ahmed al-Haj, “Yemeni rebel drones target Greek ship in government-run port,” Associated Press, October 22, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/iran-houthis-middle-east-sanaa-yemen-04ce841d3268f200e393bf7d71e767e3. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Govt Receives New Financial Support – The Yemen Review, January and February 2023,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, March 9, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/jan-feb-2023/19708. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- A low quality heavy fuel oil.

- “Govt and Saudi Arabia Reach Agreement for New Fuel Grant – The Yemen Review, September 2022,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 13, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/september-2022/18809. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- Saudi Arabia Announces US$1.2 Billion in New Financial Support – The Yemen Review, June and July 2023,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, August 15, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/june-july-2023/20631. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Houthis Ban Locally Produced Cooking Gas – The Yemen Review, May 2023,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, June 22, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/may-2023/20390. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- Casey Coombs and Majd Ibrahim, “Recovering Lost Ground in Shabwa’s Oil Sector,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, August 24, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/20682. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- Yemen Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, “Yemen Socio-Economic Update,” Issue 14, May 4, 2016, available at https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-socio-economic-update-issue-14-may-2016-enar; Wilfried Engelke, “Yemen Policy Note 2: Economic, Fiscal and Social Challenges in the early phase of a Post Conflict Yemen,” World Bank Group, May 27, 2014, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/528701508409003246/pdf/120535-WP-P159636-PUBLIC-Yemen-Policy-Note-2-edited-final-clean.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- Sana’a Center Economic Unit, “Addressing the Crushing Weight of Yemen’s Public Debt,” Rethinking Yemen’s Economy,Policy Brief No. 12, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, DeepRoot Consulting and CARPO, July 2022, https://devchampions.org/uploads/publications/files/Rethinking_Yemens_Economy_No12_En-2.pdf, p. 21. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Yemen Monthly Economic Update- December 2019,” World Bank, January 28, 2020, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/yemen/publication/yemen-monthly-economic-update-december-2019. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Special meeting | With the Minister of Oil and Minerals, Saeed al-Shammasi. The full episode (September 10) [AR],” Al-Ghad Al-Mashreq YouTube Channel, September 10, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QcQtPn1ENZU. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Quarterly Bulletin Monetary and Financial Developments,” Central Bank of Yemen, Issue No. 9, December 2022, https://english.cby-ye.com/files/64115ae274b71.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Oil Port Attacks Threaten Government Finances – The Yemen Review, October 2022,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 14, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/october-2022/19013. Accessed September 26, 2023.

- “Annual Report 2022 [AR],” Central Bank of Yemen, https://cby-ye.com/files/64a1f54c878e1.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Houthis Attack Oil Ports – The Yemen Review, October 2022,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 14, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/october-2022/19004. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- Ahmed al-Haj, “Yemeni rebel drones target Greek ship in government-run port,” Associated Press, October 22, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/iran-houthis-middle-east-sanaa-yemen-04ce841d3268f200e393bf7d71e767e3. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- Ahmed al-Haj, “Yemen: Houthi drones attack ship at oil terminal,” Associated Press, November 22, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-business-yemen-sanaa-houthis-c115994692a5c2db28f14d74895e00c3. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Yemen Economic Monitor : Peace on the Horizon? ” World Bank, October 25, 2023, https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099719410252322791/idu06b11f8f302a66040bf0adce03971527d386c. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- The Marib refinery is currently refining 7,000-8,000 barrels per day on average; approximately 3,000 barrels are allocated to cover the operating needs of power stations and army units in Marib, while the remaining 4,000-5,000 are sold locally at a price of 3,500 per 20-liter cylinder. Given that one barrel is approximately 159 liters, the estimated oil revenues the government is able to currently collect from locally refined and sold oil are about YR50 billion annually. If the same quantity were sold at YR447.5, the price stipulated under the government decree, oil revenues would reach YR139 billion annually, while if this quantity is sold at the locally imported fuel market price of YR900 per liter, it could generate an estimated YR257 billion of annual revenue for the government.

- “Houthis Ban Locally Produced Cooking Gas – The Yemen Review, May 2023,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, June 22, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/may-2023/20390. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Annual Report 2015 [AR],” Central Bank of Yemen. http://centralbank.gov.ye/App_ Upload/Ann_rep2015AR.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- Sana’a Center Economic Unit estimate.

- “Yemen’s oil and gas sector faces precarious future as peace talks intensify,” S&P Global Commodity Insi ghts, June 28, 2023, https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/062823-feature-yemens-oil-and-gas-sector-faces-precarious-future-as-peace-talks-intensify. Accessed September 26, 2023.

- Khaled Abdullah and Adel Al-Khadher, “Yemen’s Hodeidah receives first ship carrying general cargo in years amid truce push,” Reuters, February 26, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/yemens-hodeidah-receives-first-ship-carrying-general-cargo-years-amid-truce-push-2023-02-26/. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Battle to Control Imports Intensifies – The Yemen Review, March 2023,” Sana’a Center For Strategic Studies, April 14, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/march-2023/20003. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “The Governor of the Yemeni central bank reveals disastrous secrets about Yemen’s economy [AR],” Aden Hura, February 26, 2023, https://www.aden-hura.com/news/29728. Accessed Aug 28, 2023.

- “Customs revenues during 2021, an increase of 99 percent [AR],” Yemeni Customs Authority, January 20, 2022, https://customs-ye.com/posts.php?id_n=22. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- ACAPS, “Imports,” YETI | Yemen Economic Tracking Initiative, https://yemen.yeti.acaps.org/imports/. A ccessed October 25, 2023.

- “Annual Report 2022 [AR],” Central Bank of Yemen, https://cby-ye.com/files/64a1f54c878e1.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- Mohammed Mahdi Abd Obaid, Idawati Ibrahim, and Noraza Mat Udin, “An Investigation of the Determinants of Tax Compliance Among Yemeni Manufacturing SMEs Using the Fisher Model,” International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, Vol. 23, Issue 04, 2020, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/328825853.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- Danya Greenfield “Yemen’s Economic Agenda: Beyond Short-Term Survival,” Atlantic Council Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East, December 2013, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Yemens_Economic_Agenda.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- Lufti Hassen Ali al-Ttaffi, “Déterminants of Tax Non-Compliance Behavior of Yemeni SMEs: A Moderating role of Islamic Religious Perspective,” Universiti Utara Malaysia, July 2017, https://etd.uum.edu.my/7605/1/s900007_01.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- Interview with a government official, January 2023.

- Casey Coombs and Salah Ali Salah, “The War on Yemen’s Roads,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, January 16, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/19304. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Governor of the Central Bank in an Exclusive Interview [AR],” Yemen TV YouTube, June 11, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-klpWNroBZA. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “STC governor of Aden moves to block revenues to the central bank [AR],” Al-Masdar, June 12, 2023, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/275832. Accessed August 28, 2023. “STC governor of Aden moves to block revenues to the central bank [AR],” Al-Masdar, June 12, 2023, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/275832. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- Akram M. Almohamadi, “Priorities for the Recovery of the Electricity Sector in Yemen,” Rethinking Yemen’s Economy, Policy Brief No.24, DeepRoot Consulting, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies and CARPO, November 11, 2021, https://www.deeproot.consulting/single-post/priorities-for-the-recovery-and-reform-of-the-electricity-sector-in-yemen. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “The First Quarterly Report of the 2021 Oil Derivatives Grant (May to July),” Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program for Yemen, https://saudioilgrant.org/themes/bootstrap/img/report/ec838ce6a514793b9eddfbaf23e2f52b.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2023.

- “Yemen Monthly Economic Update, January 2020 ,” World Bank , February 21, 2023, https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/901061582293682832-0280022020/original/YemenEconomicUpdateJanuaryEN.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2023; p. 6: “the [telecom sector] was second to the oil and gas sector in terms of bringing in foreign currency and as a source of fiscal revenues,”

- Mansoor al-Bashiri, “Impacts of the War on the Telecommunications Sector in Yemen,” Rethinking Yemen’s Economy,Policy Brief No. 21, DeepRoot Consulting, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies and CARPO, January 11, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/12721. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- Ibid.

- “Government Approves Controversial Telecoms Deal – The Yemen Review, August 2023,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, September 14, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/august-2023/20835. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- “Inflated Beyond Fiscal Capacity: The Need to Reform the Public Sector Wage Bill,” Rethinking Yemen’s Economy, Policy brief No. 16, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, DeepRoot Consulting and CARPO, September 23, 2019, https://devchampions.org/publications/policy-brief/Inflated_Beyond_Fiscal_Capacity/. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- I bid.

- “Government Approves Controversial Telecoms Deal – The Yemen Review, August 2023,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, September 14, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/august-2023/20835. Accessed October 26, 2023.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية