Executive Summary

For decades, Yemen’s higher education system has been characterized by a persistent mismatch between graduates’ skills and the changing requirements of the market. The last labor force survey carried out in 2014 showed that less than one-third of Yemen’s labor force had secondary or tertiary education, and a qualification mismatch was found among some 83 percent of the employed population. Yemen’s struggle to produce a skilled workforce can be attributed to many factors, including inflexible curriculums, outdated teaching methods, failure to adapt to technological advancements, and a lack of strategic vision for admissions and curriculum development. Undoubtedly, the historical absence of a unified and coordinated vision for higher education has been exacerbated by a decade-long war and its detrimental impact on the country’s education system.

Against this backdrop, a presidential decree in 2022 established Al-Mahra governorate’s first university, a significant step forward for the eastern governorate, motivating young people to pursue higher education locally instead of traveling to other governorates in Yemen. Despite worthy efforts, two years after its inception, the university faces setbacks reflecting the systemic flaws encountered by many universities in Yemen. A comprehensive review of the institution’s progress reveals familiar stumble blocks, including outdated curricula and academic disciplines, stagnant teaching methods, staff shortages, insufficient resources, inadequate facilities, and limited opportunities for applied learning. Above all, the university is predominantly supply-driven, with weak linkages to the labor market, including within the governorate.

As a relatively new institution, Mahrah University has a unique opportunity to learn from past misalignment with the job market and leverage the experience of other universities, along with the countless studies and initiatives over the years that have addressed the ailments of Yemen’s higher education system. Fine-tuning its direction can help produce a skilled workforce in a resource-rich region. With approximately 500 kilometers of coastline and abundant agricultural, fisheries, and livestock, the governorate is rich in natural resources. Given its geographic location, bordering Oman and Saudi Arabia, it is also well-positioned to contribute to both the local and regional Gulf labor market by supplying competent Yemeni graduates. Al-Mahra also boasts stunning natural beauty, including the Al-Hawf Nature Reserve, which attracts local and regional tourism to a governorate that has largely escaped the impact of Yemen’s war.

In light of this context and following discussions held with local stakeholders, staff, and students from Mahrah University, this study presents solutions and directions to address the setbacks faced by the university. It suggests conducting regular, collaborative studies between the university and local employers to assess evolving market demands. Based on the findings, new disciplines and dynamic curricula could be considered, equipping graduates with the skills and knowledge required for success in today’s workforce. This could include disciples dedicated to marine sciences, agriculture, hospitality, or tourism. Additionally, innovative approaches to address faculty shortages can be implemented, optimizing resource allocation and improving the overall quality of education. The study also addresses the university’s financial and resource constraints and advocates for strategic partnerships with the private sector, civil society, donors, and local and central government entities. It also encourages mutually beneficial local relationships that provide opportunities for internships and employment for graduates to address the job market’s evolving needs. While this policy brief’s proposed recommendations primarily concern Mahrah University, the insight gained could be applied to universities across Yemen.

Recommendations

To Mahrah University

- Identify the specific labor market needs in Yemen. To ensure that programs remain relevant, the university should conduct regular, comprehensive labor market trends analysis in partnership with key public, private, and civil society stakeholders. The results of these studies should be made publicly available to students to help inform their academic and career choices.

- Refrain from introducing new academic programs until a comprehensive analysis of labor markets is conducted. By establishing a robust student database and basing decisions on the study’s findings, the university can focus its efforts on improving the quality of existing programs. If specific programs are misaligned with the job market’s immediate demands, the university should consider simplifying or reducing its course offerings.

- After completing a labor market analysis, update university programs based on the findings and collaborate closely with public, private, and civil society stakeholders to ensure graduates are taught practical skills and receive qualifications that will make them competitive in the workforce. Students will be required to demonstrate proficiency in specific competencies as a prerequisite for graduation.

- Forge strategic partnerships with the private sector to diversify funding sources. These partnerships should be aligned with the university’s academic programs and involve the development of compelling proposals for potential donors.

- Provide practical internship opportunities for students in collaboration with public and private sector organizations within the governorate. By joining forces, this initiative will create valuable internship placements that empower young people to actively participate in local development. Such collaboration, based on corporate social responsibility, will improve students’ skills and experiences while encouraging community development.

To the Internationally Recognized Government

- Provide the necessary resources to ensure Mahrah University has a regular academic staff with competitive salaries. Additionally, address the deficiencies in the university’s infrastructure, including equipment and buildings, to bring it on par with other higher education institutions in Yemen.

Introduction

Higher education institutions, along with the caliber of their graduates and areas of focus, are often key indicators of the trajectory of a country. As the global economy becomes increasingly knowledge-based, the specializations offered by these institutions are often viewed as a precursor to a country’s future, particularly its economic direction. In recent decades, Yemeni universities have undergone many transformations, including the introduction of new, technologically oriented programs, such as computer science, programming, and mechatronics, which are now widely available across Yemen’s bigger universities (Sana’a, Aden, Taiz, and Hadramawt).[1] Despite these shifts, Yemen’s higher education system has generally failed to cater to the evolving needs of the workforce, having long grappled with a misalignment between higher education outcomes and labor market demands.

These education deficits primarily stem from the failure of the relevant educational bodies to proactively anticipate market changes. Traditional teaching methods are rigid and slow to adapt to changing circumstances, as evidenced by numerous studies addressing the relationship between higher education and Yemen’s job market referenced in this paper. As a relatively new institution established in 2022, Mahrah University has a unique opportunity to overcome such misalignment. Its inaugural academic year (2023/2024) has exposed setbacks mirroring challenges faced by many universities across Yemen. Within this context, this paper examines the connection between Mahrah University and the local labor market. It proposes directions forward and recommendations that can better match graduates’ skills with employers’ needs. The study’s proposed paths forward can also serve as a foundation for future research and potentially be applied to other universities nationwide.

1.1 Methodology

This study integrates both desk research and fieldwork. A literature review of existing studies on the relationship between higher education outcomes and the labor market was carried out, and a thorough analysis of various internal documents from Mahrah University was conducted. This included information on the university’s academic programs and curriculum, governance, administration, budget policies, and statistics related to students and faculty. Additionally, the review examined the protocols for establishing new departments and programs, which include essential data on feasibility studies, labor market opportunities, the availability of qualified staff, student demand, and the experiences of similar departments at other institutions. Between July and August 2024, in-depth interviews were conducted with academics from Mahrah University and business leaders from the public and private sectors. Among them were also two members of the Al-Mahra Strategic Thinking Group (STG), who were instrumental in advocating for the university’s founding.[2] Furthermore, one focus-group discussion was carried out with students from Mahrah University in July 2024, which provided valuable insights into their perceptions of the curriculum and career aspirations. The interviews and focus group delved into various topics, including curriculum design, specializations offered, labor market demands, and strategies to enhance the alignment between graduates’ skills and employer needs.

Bridging the Gap Between Graduates and Market Demands

Traditionally, pursuing higher education in Yemen was viewed as a social aspiration rather than a means to acquire job-specific skills. Tertiary education[3] only began in the 1970s, with the establishment of the College of Education in Sana’a, which laid the foundation for the University of Sana’a. Concurrently, Aden’s College of Education became the precursor of the University of Aden. These colleges formed the backbone of Yemen’s higher education system to meet the growing demand for school teachers. The unification of North and South Yemen in 1990 led to an expansion of education institutions across the country, with 18 state universities now open in Yemen, some of which were established during the war.[4] Most of Yemen’s 22 governorates now have universities.[5]

Despite such rapid expansion, Yemen’s higher education system has remained largely unresponsive to global market transformations. Enrollment policies and specializations offered have not been adequately adjusted to meet the evolving demands of the labor market. The latest labor force survey was conducted by the International Labour Organization in 2014. The results indicated that less than one-third of the labor force had secondary or tertiary education, and qualification mismatch affected about 83 percent of the employed population.[6] In 2016, it was estimated that only 25 percent of new job seekers in Yemen are graduates of higher or vocational institutions, highlighting the severity of this predicament.[7] Among the most commonly cited challenges facing tertiary education in Yemen are a low caliber of graduates, a mismatch between graduates’ skills and job requirements, a lack of coordination between universities and the market, and outdated curricula that fail to contribute to national development.[8] On top of this, the absence of effective government intervention and a lack of engagement from the Higher Council of Universities and the Higher Education Planning Council have done little to change the status quo.

The effects of a decade-long war have also taken a toll on higher education. Funding for universities has declined. In areas under the internationally recognized government, while the amounts allocated for higher education have remained the same in nominal terms since 2014, their real value has significantly diminished due to the exchange rate fluctuation.[9] In areas under Houthi control, university budget funding has almost completely stopped, except for sporadic and minimal operating expenses. Most public sector workers, including university staff, receive around half their salary and only three or four times a year. A university professor’s salary today, for instance, has declined from about US$1,000 a month at the beginning of the war to about US$140.[10] Enrollment rates in universities have also declined, especially in the social sciences.[11] Recruitment for the frontlines has also drawn in Yemen’s youth, primarily young men, by offering regular salaries in times of extreme economic hardship, resulting in a decrease in university enrollment. In the northern part of the country, new policies introduced by the de-facto authorities promoting increased gender segregation, including in universities, are threatening to create additional barriers for female students seeking access to higher education opportunities.[12] In recent years, policy changes have also included the introduction of Houthi ideological content in university curricula, the mobilization of students for paramilitary courses, and the awarding of higher grades to students who participate in events organized by the group, along with an overall intrusion into students’ personal freedoms. These factors are contributing to a decline in university enrollment among both male and female students.

In addition, many universities have introduced parallel education programs and private fee-based courses to supplement their funding. These programs are designed for students with lower secondary school grades and require tuition payments ranging from US$300 to US$6,000,[13] depending on the specialization. Universities are simultaneously struggling to provide specialized cadres due to the brain drain resulting from the war, with many professors having emigrated to work abroad on top of the suspension of new personnel recruitment over the last decade.

Although the war has undoubtedly worsened the state of higher education in Yemen, the reality is that systemic challenges predate the conflict. The country’s National Strategy for Higher Education (2006-2010),[14] recognized the need to better equip Yemeni students with the required skills to enter the workforce by focusing on high-skilled employment and technical and vocational skills. The strategy’s implementation, however, fell short, and the status quo of higher education remains unchanged to this day despite numerous attempts over the past decades to bridge the gap.[15]

The shortcomings of Yemen’s higher education system leave many students feeling disillusioned. A study conducted by the Yemen Center for Social Studies and Labor Research in 2009 revealed that only 59 percent of university students expected to find employment upon graduation, while 40 percent did not, citing a lack of alignment between labor market demands and higher education policies.[16] As recently as February of this year, the University of Aden hosted a conference to seek ways to improve the caliber of its graduates and help them meet the evolving needs of the job market. The attendees recommended a range of measures, including curriculum reform, labor market research, and the creation of an advising center to better prepare students for their prospective careers.[17] Previous initiatives and studies all point to similar challenges and have produced similar recommendations. Ultimately, the misalignment between higher education outcomes and labor market demands continues to stand at the core of Yemen’s ailing higher education system.[18]

2.1. Mahrah University: New Institution, Familiar Challenges

The establishment of Mahrah University[19] was the culmination of a sustained advocacy campaign launched in 2018, which included extensive social media outreach and high-level meetings and workshops supported by Al-Mahra’s Strategic Thinking Group in partnership with the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. These efforts led to the opening of Mahrah University in 2022, following the issuance of Presidential Decree No. 23. The university was built upon existing academic programs in Al-Mahra, including the Education College, the Open Education Branch, and the College of Applied Sciences and Humanities in Al-Ghaydah, which were previously affiliated with Hadramawt University. The newly formed university restructured its academic framework to encompass five colleges: Education, Arts and Humanities Sciences; Administrative Sciences; Applied and Health Sciences; and Open Education.

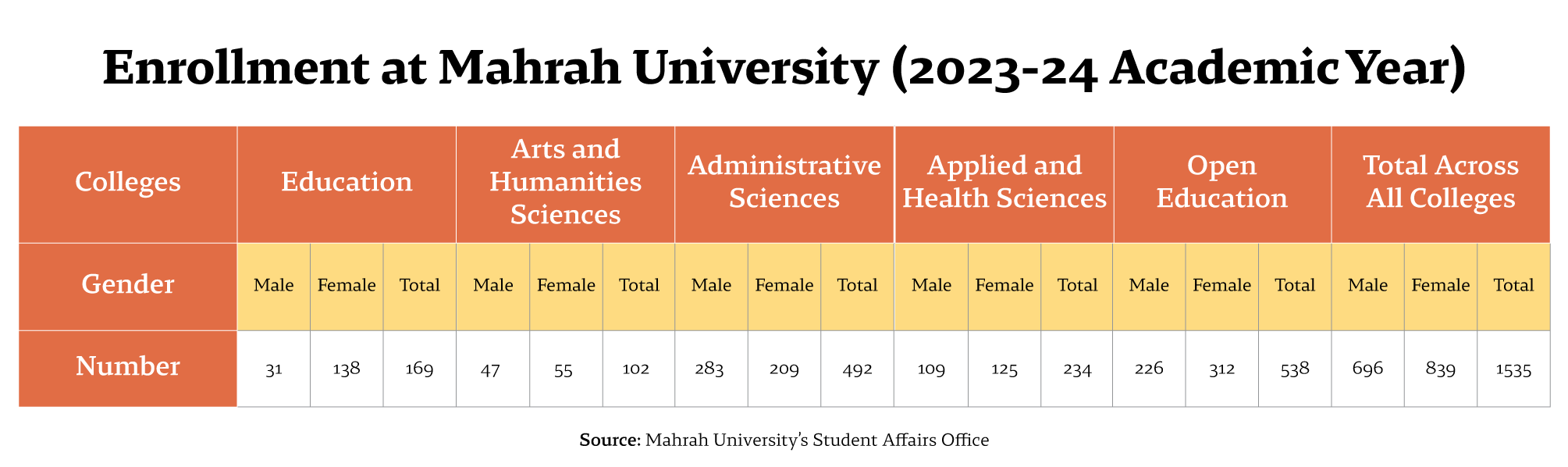

The first official academic year was 2023-24, with a total enrolment of 1,535 students. The inaugural academic year has faced several setbacks. The closure of its social science department due to low enrollment[20] underscores the consequences of misalignment between educational programs and labor market needs. This trend mirrors that of other Yemeni public universities, which have similarly struggled to anticipate labor market demands and have been forced to shut down departments and programs due to low enrollment.

The financial sustainability of Mahrah University is also uncertain. It heavily relies on funding from the Al-Mahra local authority (70 percent). A modest contribution comes from the central government (15 percent), even though financing public universities is the responsibility of the central government. The remaining funds are generated from distance learning fees.[21] Establishing a university without sufficient operational and research budget is misguided, especially given the government’s financial constraints.[22] A comprehensive review of Mahrah University’s records revealed familiar challenges. These include outdated curricula and academic disciplines, stagnant teaching methods, staff shortages, insufficient resources, inadequate facilities, and limited opportunities for applied learning. The university is also predominantly supply-driven, with weak linkages to the labor market, including in the governorate. The following section details the primary difficulties facing Mahrah University and proposes solutions and future directions based on consultations and discussions held with Al-Mahra’s academic staff and students and the researchers’ experience in Yemen’s education sector.

The financial sustainability of Mahrah University is also uncertain. It heavily relies on funding from the Al-Mahra local authority (70 percent). A modest contribution comes from the central government (15 percent), even though financing public universities is the responsibility of the central government. The remaining funds are generated from distance learning fees.[21] Establishing a university without sufficient operational and research budget is misguided, especially given the government’s financial constraints.[22] A comprehensive review of Mahrah University’s records revealed familiar challenges. These include outdated curricula and academic disciplines, stagnant teaching methods, staff shortages, insufficient resources, inadequate facilities, and limited opportunities for applied learning. The university is also predominantly supply-driven, with weak linkages to the labor market, including in the governorate. The following section details the primary difficulties facing Mahrah University and proposes solutions and future directions based on consultations and discussions held with Al-Mahra’s academic staff and students and the researchers’ experience in Yemen’s education sector.

Systemic Obstacles Facing Higher Education: Mahrah University as a Case Study

3.1. Outdated and Conventional Academic Disciplines

Students enrolled at Mahrah University viewed the establishment of a university as a significant step, motivating young people in the governorate to pursue higher education. This particularly appealed to those who had previously been deterred by the long distances to other universities in Yemen and who preferred not to study abroad. With approximately 500 kilometers of coastline and abundant agricultural, fisheries, and livestock, Al-Mahrah is rich in natural resources. Given its geographic location, bordering Oman and Saudi Arabia, it is also well-positioned to contribute to both the local and regional labor market by supplying competent Yemeni graduates. The region also boasts stunning natural beauty, including the Al-Hawf Nature Reserve, which attracts local and regional tourism to a governorate that has largely escaped the war.[23] Notably, no colleges or departments are currently dedicated to marine sciences, agriculture, hospitality, or tourism. Upon enrollment, many students found that their desired programs were unavailable. Among five students interviewed, only one could study their preferred field of dentistry following its introduction last year. Those aspiring to study engineering had to settle for information technology.[24] The university’s rollout phase has not aligned with the local economy, environment, and labor market needs in the governorate. Instead, it has largely retained the specializations and departments inherited from the University of Hadramawt, with only a few exceptions, such as renaming a few colleges and adding new programs like physics, dentistry, and marketing.

By better analyzing the geographic scope of their target labor market, Yemeni universities can tailor their educational programs to meet employers’ specific needs and expectations. This requires a two-level approach: (1) improving the performance of existing programs while eliminating those that are no longer relevant. Such a process would need at least four years to phase out these departments; and (2) strategically develop new programs in collaboration with public and private sector employers who would provide initial financial support. This should be accompanied by agreements for training and absorbing graduates, focusing on promising and currently underserved sectors such as fisheries, environment, and tourism. To effectively implement this policy, a robust legal framework must be established that empowers the university administration to take decisive action. The Ministry of Higher Education and the Supreme Council for Higher Education are the leading authorities responsible for higher education policies, but the 2006-2010 higher education strategy still needs to be updated. In its absence, close collaboration with local authorities and relevant government agencies is essential.

To address the university’s significant financial deficits, a comprehensive plan that outlines the goals, activities, and budget for each proposed initiative is critical. These plans should be presented to local and central authorities through joint committees involving university representatives and labor market stakeholders. A small yet influential group of stakeholders can serve as powerful advocates aiding the university in lobbying policymakers.

3.2. Archaic Teaching Methods and Curricula

Except for the College of Applied Sciences, a significant portion of the curriculum offered at Mahrah University remains rooted in the pre-existing frameworks of colleges formerly associated with the University of Hadramawt.[25] Upon its inception, Mahrah University established a curriculum mapping center guided by a program developed by a specialized academic committee.[26] Other academic committees were also tasked with drafting and disseminating course materials to colleges and staff as instructional plans.[27] The prevailing teaching method, however, relies heavily on rote memorization, with many tutors rigidly adhering to their lecture notes to ensure students pass exams. This overemphasis on memorization as a measure of learning hinders the development of critical thinking, creativity, and the ability to adapt to evolving technological landscapes. Teaching methods need to be improved. For instance, focus group discussions held with Mahrah University students revealed that accounting students are still using manual accounting rather than contemporary accounting software that has become the industry standard.[28]

The curriculum must be a dynamic component, continuously evolving and aligned with the needs of stakeholders in the industry. As a first step, efforts should focus on two key areas: 1) to remain relevant and practical, the curriculum must be regularly updated and reviewed every four years, and 2) to remain flexible enough to accommodate ongoing changes. By aligning the curriculum with the changing demands of the job market and clearly outlining the practical skills students need to master, graduates can be better prepared for a successful career. To facilitate this, the university must invest in modern equipment and laboratories and adopt innovative teaching methods that leverage technology.[29] Furthermore, faculties must have the latest pedagogical tools and techniques to deliver engaging and practical education. Over time, curricula will develop through strategic partnerships between the university and various stakeholders, including government, industry, and civil society. This collaborative approach can also encourage public-private partnerships that fund initiatives with the help of international donors.

3.3 Shortage of Staff

Mahrah University is experiencing a quantitative and qualitative shortage of academic staff, arising from the inability to offer competitive salaries, relocation allowances, and housing benefits to attract faculty outside the region. Most of the university’s academic staff are contract-based employees rather than permanent faculty. Many of the instructors are ill-equipped to engage students in meaningful learning experiences, often resorting to a rigid adherence to textbooks and course material.[30] Despite student complaints about ineffective teaching, the university administration has been unable to take appropriate action due to a lack of qualified replacements.[31] The salaries are too low to attract prospective candidates. Some, coming from war-torn areas, are willing to overlook the inadequate compensation due to their limited options.[32] If a candidate agrees to join the institution despite the meager salary, their financial constraints will inevitably affect their ability to perform effectively. The compensation often fails to meet their basic needs, leading some faculty members, especially those relocating from other regions, to leave their positions.

The university can implement a multi-faceted strategy to address the quantitative shortage, beginning with short-term measures. For example, the course schedule for affected students can be condensed, and opportunities for remote learning could be explored.[33] Furthermore, coordination and cooperation with neighboring universities, such as the University of Hadramawt, can be explored to share faculty resources and thus cover the shortage at Mahrah University as part of broader inter-university collaboration. The university can consider recruiting volunteer instructors from the Yemeni diaspora to access a broader range of expertise. These individuals may be willing to support their country during these challenging times by contributing their time and knowledge pro bono. Addressing the qualitative gap, on the other hand, requires a concerted effort to train and develop existing faculty and cultivate new talent. One potential solution is establishing a graduate program to prepare high-achieving students for academic careers. Crucially, these needs must be explicitly outlined in a comprehensive development plan, specifying the required qualifications and quantity of faculty. This policy requires a proactive assessment of the nature, type, and extent of the faculty shortage by the administration of each college and at the university level.

3.4 Resource Scarcity, Inadequate Facilities, and Aging Infrastructure

A computer laboratory, furnished with 25 workstations (a portion of which are non-operational) and sustained by two solar batteries, caters to a student population of over 70 in Mahrah University’s computer science department. Due to capacity constraints, students are compelled to access the laboratory in groups. However, the intermittent power supply from the solar batteries frequently results in the depletion of power reserves during later sessions, thereby hindering practical application opportunities.[34] This scenario exemplifies the severe issue of inadequate resources.[35] Laboratories, teaching equipment, classrooms, facilities, and the limited number of available computers must be increased. Computer science students, in particular, often require more personal devices for home-based practice when laboratory access is limited. Furthermore, students are expected to supply some of their own equipment.[36]

The university has also relied on repurposed buildings of colleges affiliated with the University of Hadramawt. The university’s administration is still housed in rented premises. It faces a budget deficit and needs help to afford even contractual salaries. So far, the Al-Mahra local authority has borne the university’s financial burden. It has provided significant funding for contract employee salaries, building equipment, incentives, and housing for staff from outside the region. Given its limited financial resources, however, it has been unable to fully support the university’s needs, despite contributions from businesses and entities like oil companies, which have provided equipment such as solar energy and security systems.[37]

To secure adequate funding and resources, the university must demonstrate its capacity to produce exceptional graduates who can substantially contribute to society. By showcasing its achievements, the university can lobby for increased funding from the central government, local authorities, and other stakeholders belonging to the private sector or international donors. Whether lobbying for an independent budget or demonstrating its value to secure more significant support, the university must articulate its needs and potential for growth.

Internationally or regionally funded initiatives in Yemen offer a promising avenue for securing interim, project-based financing. Moreover, the governorate’s private sector and public revenues, mainly customs fees collected at the Yemen-Oman border, present viable options. A practical proposal could include earmarking a portion of customs duties on vehicles entering through a designated port to fund the establishment of an environmental studies department at the university. Funds would be deposited into a dedicated account for a specified duration. Similarly, fish canning factories could allocate specific resources to fund a marine biology department in collaboration with the Chamber of Commerce, Industry, and Local Authorities. The university should integrate such initiatives into a comprehensive plan, outlined as detailed, practical, and executable partnership projects governed by transparent and fair policies.

3.5 Neglect of Applied Learning

Almost every college has specializations that require practical application, whether in the public sector, such as education, or the private and public sector, such as accounting, computer science, dentistry, and information technology. Although limited internships are available at institutions like the CAC Bank, a Yemeni bank with branches across all governorates, including Al-Mahra,[38] these typically involve theoretical exposure to banking operations rather than hands-on experience. Such opportunities are often facilitated through individual initiatives rather than organized university programs. Accounting students, for instance, face challenges in securing internships at exchange houses and the few banks in the governorate that utilize modern accounting software, as these businesses are hesitant to risk their systems by providing hands-on experience to students unfamiliar with such software.[39]

The College of Applied Sciences mandates practical applications as a core component of its curricula. Nonetheless, the adequacy of equipment and facilities often falls short, forcing students to rely on self-directed learning and online resources. Collaborative projects with government entities like electricity companies provide some hands-on experience. Despite the significant emphasis placed on practical skills, as evidenced by the allocation of up to 50 percent of course credit hours to practical assessments, the overall success rate of students remains at approximately 70 percent.[40] This indicates that while students can generally meet the minimum requirements, the quality and quantity of practical experiences within and outside the college are suboptimal.

To improve off-campus internship opportunities, the university administration should facilitate collaborations with the private sector that are aligned with students’ respective majors.[41] By forging strategic partnerships with private sector entities such as oil companies, telecommunications firms, banks, and broadcasting stations, as well as hospitals and medical centers for dental students, the university can provide students with valuable practical experience that aligns with contemporary technological advancements.[42] This initiative should entail relevant entities acting as training partners to actively participate in their corporate social responsibility.[43] Simulation-based training can be initiated within the university, providing students with hands-on experience with industry-standard accounting software as an interim measure. This approach can address concerns held by commercial companies regarding student access to sensitive financial data and potential misuse of their systems due to lack of expertise.

Conclusion

Al-Mahra governorate, with a population of approximately 175,600,[44] possesses a unique labor market characterized by its relatively small size and significant growth potential. The influx of displaced individuals has expanded economic opportunities and created a demand for skilled workers in various sectors. While the labor market is still developing, there is a particular need for technical and administrative professionals and medical practitioners. [45]

Mahrah University’s strategic focus, however, remains vague two years after its inception. It is unclear whether the university’s primary goal is to cater to the local job market, the national Yemeni market, or the broader Gulf market. With only 30-40 percent of the student body originating from within the governorate and 60-70 percent coming from outside, primarily due to the displacement caused by the war,[46] it is evident that the university’s programs and enrollment numbers should be tailored beyond the local job market, especially considering the expanding opportunities for remote work.

The mismatch between the specializations offered by Mahrah University and those demanded in the current job market works to the detriment of its students. Fields such as civil engineering, electricity, medical sciences, accounting, programming, and information technology are either absent or lack the necessary practical components to equip graduates with the skills required by industry.[47] Moreover, sectors like economics, finance, and banking have specific skill requirements that are not currently being met.[48] Given the governorate’s unique characteristics, there is a pressing need for programs in agriculture, fisheries, veterinary medicine, environmental science, tourism, languages,[49] marine sciences, and fisheries.[50] The History and Geography departments, closed due to low enrollment, should also be reopened. This will help meet the region’s demand for teachers while also providing additional incentives to attract students.[51]

To align graduates with the job market, universities must adopt a strategic approach. This involves clearly defining the target market, conducting a comprehensive analysis of its needs and future trends, and developing policies informed by this analysis. Successful implementation requires collaboration with public and private stakeholders to ensure that all aspects of the academic program, from curriculum development to career placement, are aligned with market demands.

Labor market analyses should be an ongoing endeavor conducted in partnership with representatives from the private sector, universities, and relevant local and national entities. The International Labour Organization supported the last labor force survey for Yemen in 2014.[52] However, universities must introduce a more standardized national framework to facilitate the exchange of data and information, with key indicators published on a dedicated platform or integrated into university websites. By creating a labor market research unit within each university, findings from regular studies can directly inform the development and updating of university policies at all levels. This includes creating and eliminating academic programs based on market demand and revising curricula and training programs.

To effectively support students in their careers, universities should establish and maintain a comprehensive database detailing market trends, employment opportunities, and the skills employers seek. This database should be accessible to prospective and current students, giving them the information they need to make informed decisions about their academic and career paths. Moreover, universities should implement a robust alumni tracking system to gather data on graduates’ post-graduation outcomes. By analyzing this data, institutions can identify areas where graduates may need additional support and tailor their programs accordingly. Inviting industry experts to speak to students can provide valuable insights into the skills and knowledge required for success in the workplace.

Finally, a comprehensive legislative framework is needed to grant university administrations the authority to make these decisions in coordination with local authorities, the Ministry of Higher Education, and the Supreme Council of Universities. Civil society must also actively advocate for and oversee these initiatives to encourage trust among stakeholders. By integrating development, labor market, and educational enhancement components into their projects and activities, civil society organizations can contribute significantly to these efforts. Ultimately, the success of these endeavors hinges on the university’s ability to build trust, maintain transparency, foster innovation, and effectively execute agreed-upon policies.

Key Recommendations

To Mahrah University

- Identify the specific labor market needs in Yemen. To ensure that programs remain relevant, the university should conduct regular, comprehensive labour market trends analysis in partnership with key public, private, and civil society stakeholders. The results of these studies should be made publicly available to students to help inform their academic and career choices.

- Refrain from introducing new academic programs until a comprehensive analysis of labor markets is conducted. By establishing a robust student database and basing decisions on the study’s findings, the university can focus its efforts on improving the quality of existing programs. If specific programs are misaligned with the job market’s immediate demands, the university should consider simplifying or reducing its course offerings.

- After completing a labor market analysis, update university programs based on the findings and collaborate closely with public, private, and civil society stakeholders to ensure graduates are taught practical skills and receive qualifications that will make them competitive in the workforce. Students will be required to demonstrate proficiency in specific competencies as a prerequisite for graduation.

- Forge strategic partnerships with the private sector to diversify funding sources. These partnerships should be aligned with the university’s academic programs and involve the development of compelling proposals for potential donors.

- Provide practical internship opportunities for students in collaboration with public and private sector organizations within the governorate. By joining forces, this initiative will create valuable internship placements that empower young people to actively participate in local development. Such collaboration, based on corporate social responsibility, will improve students’ skills and experiences while encouraging community development.

To the Government of Yemen

- Provide the necessary resources to ensure Mahrah University has a regular academic staff with competitive salaries. Additionally, address the deficiencies in the university’s infrastructure, including equipment and buildings, to bring it on par with other higher education institutions in Yemen.

- Universities in Yemen are also witnessing a decline in popular humanities majors, such as psychology, history, and geography.

- The STG consists of a diverse team of local politicians, community leaders and young activists. It was formed in four Yemeni governorates (Marib, Hadramawt, Shabwa and Al-Mahra), as part of the “Exploring Alternative Methodologies for Peace” project implemented by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies in partnership with Saferworld and funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO). Al-Mahra’s strategic thinking group actively advocated for the establishment of Al-Mahrah University. It organized multiple meetings with local authorities and relevant governmental, academic, and administrative entities in the governorate, and was also behind an online advocacy campaign under the hashtag #CompleteTheAlMahraUniversityDecree. These efforts led to the issuance of Presidential Decree No. 23 of 2022, which established Al-Mahrah University. This paper forms part of the group’s proposals to shed light on the reality of higher education in Al-Mahra governorate.

- Higher education programs in Yemen include i) two-year programs leading to an intermediate diploma, a technical diploma, a technician certificate, and a teacher’s certificate (preschool and primary education teacher); ii) three-year programs offered by Community colleges and leading to an associate degree; iii) bachelor’s degree programs that normally last four years (five years in the case of engineering; six years in the case of medicine) and at the postgraduate level, there are one-year programs leading to a postgraduate diploma (higher, specialist, graduate, or preparatory diploma). Master’s programs generally last two years to complete, while doctorate programs take at least three to four years. Yemen’s Technical Education and Vocational Training sector also offers students two three-year programs in vocational sectors. See Michele Bruni, Andrea Salvini and Lara Uhlenhaut, “Demographic and Labour Market Trends in Yemen,” International Labour Organization, 2014, https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@arabstates/@ro-beirut/documents/publication/wcms_358144.pdf

- Adel Al-Sharjabi, “Yemen: The Conditions of Public Education in Times of War,” Yemen and Gulf Center for Studies, October 8, 2023, https://ygcs.center/en/studies/article51.html

- The last unified annual census for Yemen pre-war was for the academic year 2013/2014. According to the annual statistics book, issued in 2015, the number of public universities was 10, with 227,174 students, 34.5 percent of whom were female, and the number of students in private universities, 27 at the time, was 83,179, 27.7 percent of whom were female.

- “Yemen Labour Force Survey 2013-2014,” International Labour Organization, 2015, https://www.ilo.org/publications/yemen-labour-force-survey-2013-2014

- Abdullah Al-Tuqi and Abdullah Al-Adhi, “Trends in the Yemeni Labor Market,” Al-Andalus Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, Issue 10, Volume 13, April 2016, p. 96.

- Radfan Abdul-Habib Abdullah Qasim, “Impact of University Education Outcomes on the Labor Market in the Republic of Yemen for the Period (1998 – 2012),” University of Aden, Journal for Humanity and Social Sciences, June 2023, p. 381.

- In 2014, US$1 was equivalent to 215 Yemeni riyals, but by late 2024, the exchange rate had soared to over 2,000 riyals per US$1.

- Fahmi Khaled, “A War of Attrition: Higher Education in Yemen,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, March 26, 2024, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/22091#:~:text=Over the past eight years,been properly taught fundamental skills

- In 2014, the number of students in the Arabic Language Department at Sana’a University was 300 male and female students. In 2023, the number declined to 26 male and female students in the department. Moreover, student enrollment in the philosophy and history departments has drastically dropped, although these were highly popular ones among students. Each department had just one student in the year 2023. Fahmi Khaled, “A War of Attrition: Higher Education in Yemen,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, March 26, 2024, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/22091#:~:text=Over the past eight years,been properly taught fundamental skills.

- Ismail Al-Aghbari, “Gender Segregation at Sanaa University: A Worrying Trend for Yemen,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 26, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/2023/09/gender-segregation-at-sanaa-university-a-worrying-trend-for-yemen?lang=en

- Adel al-Sharjabi, “Yemen: The State of Public Education in Wartime,” Yemen and Gulf Center for Studies, October 8, 2023, https://ygcs.center/ar/studies/article43.html

- The National Strategy Document for Higher Education in the Republic of Yemen and the Future Action Plan 2006-2010, p. 12.

- In 2008, a conference entitled “Higher Education Outcomes and the Labor Market” issued recommendations to integrate practical training components into all academic programs, regularly update curricula every five years, and establish early career guidance programs for students. “Higher Education Conference under the slogan Higher Education Outputs and the Labor Market,” SABA, March 13, 2008, https://yemennic.net/archives/2145. In March 2021, the University of Science and Technology, the largest and most important private university in Yemen, convened a discussion on aligning university graduates with labor market demands.

- 41 percent of Yemeni university graduates do not expect to obtain job opportunities,” Al Masdar Online, June 9 2010, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/52545

- “Recommendations issued by the consultative conference to improve the quality of Aden University’s outputs in line with labor market requirements,” Aden University, February 26, 2024, https://www.ADEN-univ.net/oldnews/22181

- Numan Ahmed Ali Abdullah Fairouz, “Extent of the Adaptation of Yemeni University Outputs to the Needs of the Labor Market: Ibb University as a Model,’ University Research Journal for Humanities, Issue 32, March 2017, p. 241.

- Editor’s note: The Sana’a Center has made a deliberate choice to keep the spelling of Al-Mahra governorate consistent with our style guide and past work. Mahrah University is spelt in line with the university’s branding in English.

- An internal report provided by the Students Affairs Office indicates that programs such as Islamic Studies, Arabic Language, Geography, and Psychology were closed due to the lack of new students applying to these departments.

- Based on a memorandum obtained by the researcher from the office of the Secretary-General of Mahrah University.

- Arguably, the decision to establish a university needed a more thorough study to ensure they had the resources to operate a higher education institution efficiently.

- Despite the decade-long war, Al-Mahra has remained relatively unaffected by direct military conflict and is considered as a popular destination for Yemenis and Gulf nationals.

- Focus group discussion with male and female students from Mahrah University, July 9, 2024.

- Interview with Dr. Naji Balhaf, Vice Dean of the College of Administrative Sciences, July 29, 2024.

- Ibid.

- Interview with an academic at the College of Education, Mahrah University, July 11, 2024.

- Focus group discussion with male and female students from Mahrah University, July 9, 2024.

- Despite clear funding challenges such initiatives can be cost-effective if financed through collaborative efforts with invested partners. The curriculum development process will be integrated into a broader strategic plan presented to partners.

- Focus group discussion with male and female students from Mahrah University, July 9, 2024.

- Ibid.

- Interview with the Vice Dean of the College of Applied Sciences at Mahrah University, July 16, 2024.

- If a course typically requires 18 hours over a three-month semester, a temporary instructor can be contracted to teach the course for three hours daily for one week, thereby reducing costs.

- Focus group discussion with male and female students from Mahrah University, July 9, 2024.

- Interview with an academic at the College of Education, Mahrah University, July 11, 2024.

- Focus group discussion with male and female students from Mahrah University, July 9, 2024.

- Interview with the Vice Dean of the College of Applied Sciences at Mahrah University, July 16, 2024.

- Interview with Dr. Abdul Sami Al-Shami, Director of Mahrah Credit Bank, on July 23, 2024.

- Ibid.

- Interview with the Vice Dean of the College of Applied Sciences at Mahrah University, July 16, 2024.

- This initiative could be overseen by a university-established monitoring and coordination committee and incorporated into the practical training curriculum for marketing students. The committee should then be expanded to include representatives from local government, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and civil society. These incentives should be formalized within the university’s comprehensive plan for a more sustainable approach, outlining specific partners and resources to accommodate future growth. Furthermore, each college should have a dedicated training department and a specialized training officer to oversee in-study training.

- Interview with the Vice Dean of the College of Applied Sciences at Mahrah University, July 16, 2024.

- To incentivize participation, tangible and intangible rewards can be offered to responsive organizations, such as naming a training facility or graduating class in their honor.

- Yemen Conflict Observer, Regional Profile Al-Mahra, ACLED, January 31, 2024, https://acleddata.com/yemen-conflict-observatory/region-profiles/Al-Mahra/#:~:text=Although the second largest governorate,a population of about 175,600.

- Interview with the Deputy Dean of the College of Applied Sciences at Mahrah University, July 16, 2024.

- Approximate estimates given by participants in the focus group discussions, and confirmed by Dr. Naji Balhaf, Vice Dean of the College of Administrative Sciences.

- Focus group discussion with male and female students from Mahrah University, July 9, 2024.

- Interview with Dr. Abdul Sami Al-Shami, Director of Mahrah Credit Bank, July 23, 2024.

- Interview with the Director of a Trading and Contracting Company in Mahrah, August 7, 2024.

- Interview with Dr. Naji Balhaf, Vice Dean of the College of Administrative Sciences, July 29, 2024.

- Interview with female leader and academic at the College of Education, Mahrah University, July 11, 2024.

- Yemen Labour Force Survey 2013-2014, International Labour Organization, 2015, https://www.ilo.org/publications/yemen-labour-force-survey-2013-2014

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية