On a Sunday night more than three years ago, Rawan, 15, was squeezed onto a motorcycle with her sister and two brothers as their father, Abdulbari Yahyah Farea, sped them away from fighting near their home by Hudaydah airport. The motorcycle struck a landmine, with the explosion killing Rawan’s father and two brothers, 3 and 8, instantly. Rawan was slightly injured and tried to drag her severely wounded sister, Hanan, 10, to relative safety. Rawan spent the next 12 hours on the phone with UN aid workers, who provided first aid guidance until her phone battery died. Hanan was still losing blood. UN officials eventually got an ambulance to the girls, following extensive calls to Houthi authorities in Sana’a and the Saudi-led coalition in Riyadh.

Hanan died in hospital; Rawan now lives with her grandparents. Her uncle, who relayed the events of June 2018, said the family is doing everything it can to help Rawan move on and live her life. “It has been a very traumatic experience for her,” he said. “Losing your father, all your brothers and sister all at once and in that way is something that no one can just put up with or leave behind.”

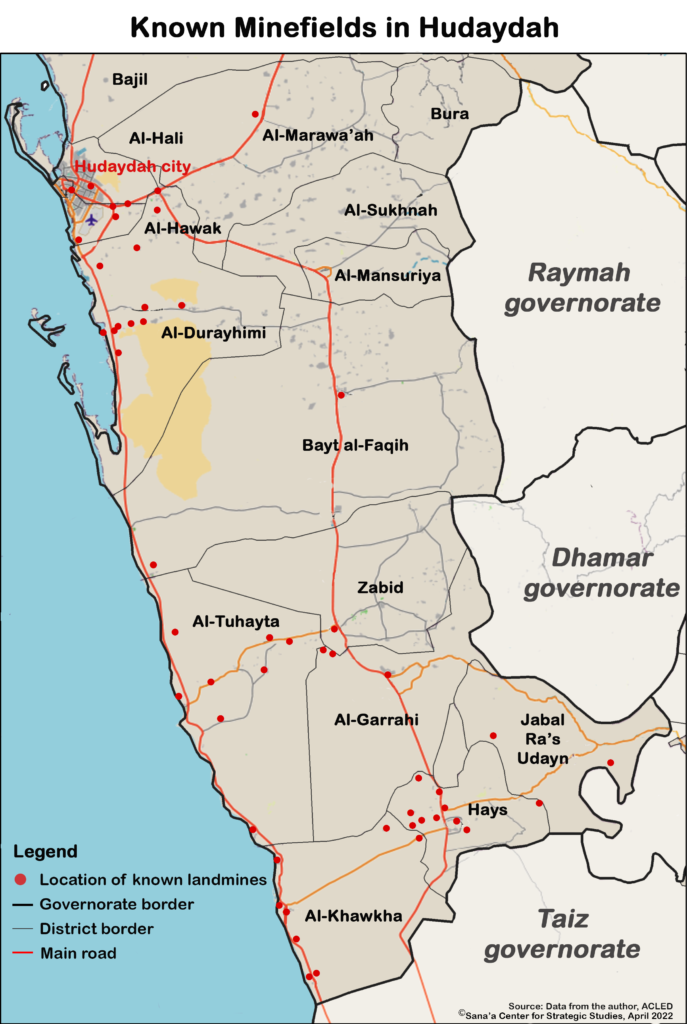

Frontlines finally shifted away from Yemen’s Red Sea city of Hudaydah late last year, but residents of the city’s sprawling eastern and southern outskirts remain surrounded by the thousands of landmines planted since mid-2017, which, according to ACLED data, have killed at least 832 people since then. During most of that time, only one road out of the city of roughly 700,000 was open, but when government-allied forces pulled back in November 2021, Houthi forces fanned out and reopened roads in areas that had been largely abandoned when the war closed in. More tragic explosions followed.

Among those reported thus far this year, a landmine killed brothers Abdo and Ali Deedo in January, when they went to inspect the Yemen Oil Company’s gas storage facility 10 kilometers east of Hudaydah city, which was shut down during fighting in 2018. On arriving, one brother stepped on a mine; both were killed and a third worker was critically injured. In March, five relatives died when the pickup truck they were riding in struck a landmine in the same area, and, four days later on March 20, a young couple and their 4-year-old daughter were injured by a mine in the Kadah area of the southern district of Al-Khawkhah. On April 11, Mohammed Aqlan, a member of the Hudaydah Traffic Police, returned from years of displacement to check his house on the city’s northern outskirts; he stepped on a mine, losing one leg and severely fracturing the other.

Digging In and Planting Mines

Houthi forces were entrenching their defensive positions on the southern outskirts of Hudaydah in June 2018 as forces backed by the Saudi-led coalition were advancing on the city to retake it. Thousands of families were packing up and leaving Hudaydah city to seek safety elsewhere. Streets were blocked as trenches and roadside barriers went up; businesses shut down and most recreational activities came to a halt. The Joint Forces, a cluster of government armed forces and local resistance fighters backed by the UAE and Saudi Arabia, aimed to retake the key port city – then Yemen’s busiest gateway for commercial imports and humanitarian aid.

By the time the Joint Forces reached the outskirts of Hudaydah city, fighting had already consumed not only Al-Tuhayta area, about 120 kilometers south of Hudaydah city, but also southern Hudaydah districts including Al-Durayhimi, Al-Khawkhah and Hays. On December 13, 2018, the warring parties signed the UN-brokered Stockholm Agreement, which included a cease-fire agreement in Hudaydah city and its three seaports as well as plans to demilitarize the city through redeployment of the warring parties. The redeployment, however, never fully materialized. And in southern Hudaydah, continued fighting forced many families to flee, sometimes multiple times, as frontlines shifted. Today, large swathes of land remain littered with combatants’ mines and unexploded abandoned shells. Demining teams are active in southern Hudaydah, slowly locating, disarming and collecting devices buried in former frontline areas.

While total numbers are not known, either for Hudaydah governorate or nationally, more than 334,000 explosive devices have been cleared throughout Yemen since mid-2018, according to Project Masam, a Saudi-funded de-mining project. Since then, Masam, working with the Yemen Executive Mine Action Center (YEMAC), have reported clearing 4,960 anti-personnel mines, 123,355 anti-tank mines, 7,345 Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) and 198,400 pieces of Unexploded Ordnance (UXO).

Landmines as a Neighborhood Menace

Several residents of Hudaydah city, including in the heavily mined eastern and southern outskirts where so many industrial plants, family-owned plantations and animal farms shut down or moved during the fighting, spoke of watching the Houthis lay mines in and near their neighborhoods in recent years. “There are no warning signs,” said a 37-year-old resident of Al-Rabasa neighborhood, on the eastern edge of the city, adding that residents were only told to avoid certain areas.

On the south side of Hudaydah city, Houthi forces mined roadside barriers. “You see those big (40-foot/12-meter shipping) containers? They were filled up with sand and mines,” said one resident who asked not to be named, fearing reprisals. “We were simply told not to come near any of them.” Only recently have several of the containers been removed along the city’s eastern and southern edges.

Even the northern city perimeter, where the only entry and exit point for the city was located, remained infested with mines in anticipation of Joint Forces activity. Barbed wire was put up on roadside barriers there; landmines have exploded behind it.

Outside the port city, Houthi forces laid landmines in southern Hudaydah, particularly in territory they controlled near frontlines just outside Al-Durayhimi district and in several parts of Al-Tuhayta, Al-Khawkhah and Hays. Local residents confirmed seeing some mining activity by government-allied Joint Forces, mostly in areas between Al-Tuhayta and Al-Khawkhah. However, the sheer numbers of mines laid by Houthi forces in the governorate raises compelling questions about their origins. According to a September 2018 Conflict Armament Research (CAR) report, the Houthis have domestically improvised and produced the “vast majority” of landmines in southern Hudaydah. They reportedly seized anti-tank mines and modified them to explode with only about 10 kilograms of pressure instead of 100 kilograms. Such sensitivity means a young child’s weight could detonate them.

More People on the Move in Mined Areas

From January 2021 to early April 2022, landmines planted by Houthi forces along with unexploded explosive ordnance had killed or wounded 363 civilians in a number of governorates, according to Yemeni Landmine Records, which compiles information on victims of landmines and UXO in the country. Most of these incidents, in which the observatory said 176 people were killed and 187 were wounded, many of them children, occurred in the southern coastal districts of Hudaydah. A cluster of September-October 2021 incidents included:

- In mid-September, a minivan carrying 15 people exploded, including 11 children – mostly members of one extended family from Al-Khawkhah district. Everyone aboard was injured, many of them seriously.

- In early October, a pregnant woman stepped on a Houthi-laid mine on the eastern outskirts of Hudaydah city, near the Red Sea Mills. The 35-year-old lost her baby and both of her legs.

- Later in October, a member of a mine-clearing team was seriously injured while removing landmines in the same area. He lost a leg.

- One week later in Al-Durayhimi, a motorcycle carrying two children, ages 12 and 17, and a 60-year-old man, struck a mine, killing all three. A relative of the 12-year-old victim, Hamood Jaber Ayyash, said residents’ options are limited to death by landmines or displacement, adding that “living as a displaced person near mined-infested areas is a death sentence in itself.”

The Joint Forces’ unexpected pullout from around Hudaydah city on November 12 left the Houthis to sweep into these areas. It also prompted a new wave of displaced people, while allowing local residents to move more freely throughout much of Hudaydah governorate. Houthi forces opened all roads leading to Hudaydah city, including those in the heavily mined areas of its eastern and southern perimeter. Although demining efforts are underway, thousands of mines remain hidden beneath the soil.

Al-Durayhimi district, 23 kilometers south of Hudaydah and the epicenter of battles in the governorate, remained largely closed off, with only a handful of families briefly allowed to check on their houses. Some people from Al-Durayhimi, who relocated to neighboring areas, said landmines still litter the district.

“I was allowed to see my house after I spoke with a number of Houthi field supervisors,” one person said. “When I opened one of the rooms, I saw it was stacked full with landmines. I just closed it and left the place.”

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية