Since the outbreak of the war, Yemenis have sought to escape the scourges of violence, economic collapse, and political instability. Some have made arduous journeys to Djibouti, Somalia, and Somaliland[1] on small fishing boats to reach safety,[2] and now reside in their respective capitals.[3] Others have sought refuge in Ethiopia, where they are mostly found in remote areas on the outskirts of Addis Ababa.[4] A number have been able to reach Jordan and Egypt, most of whom now live around Al-Jubeiha in northern Amman,[5] or in the Faisal, Ard al-Lewa, and Al-Duqqi areas of Cairo.[6] Many refugees, particularly those who fled to Egypt and Jordan early in the conflict, believed it would only be a matter of weeks or months before the war came to an end and they could return home. But as the conflict has dragged on, their living conditions have deteriorated, forcing large numbers to register with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to obtain assistance and establish their legal status.[7]

Surviving as refugees is a recent phenomenon for Yemenis, emerging after the 2011 political crisis and the outbreak of war in 2015. The ongoing conflict and deteriorating economic and security conditions have led to an escalation of forced migration and displacement, as residents flee persecution, armed conflict, and human rights violations. According to the UN, more than 19 million people will face hunger in Yemen this year, and nearly 160,000 Yemenis are already on the edge of famine.[8] Since the start of the war in March 2015, 4 million Yemenis have been displaced, and although some 1.3 million have returned to their homes, most are still at risk.[9]

This report highlights the situation of Yemeni refugees registered with the UNHCR in Egypt, Jordan, Somalia, Somaliland, and Ethiopia, examining and analyzing the way the organization deals with refugees in these countries and the challenges they face. It focuses on the role played by the UNHCR and partner organizations in providing protection to Yemeni refugees and dealing with them under established international legal frameworks. Current deficiencies make clear the need for a reassessment of how the international community deals with Yemeni refugees.

While Yemenis receive refugee cards from the UNHCR, activists, and refugees claim that access to the services guaranteed under humanitarian law and the Refugee Convention is unequal, and allege that their resettlement rate remains low compared to refugees from other countries. According to activists and applicants, European states and the US, many of whom are signatories of the 1951 Refugee Convention, have refused to receive Yemeni refugees or allocate a quota for resettlement. Many of those interviewed believe the reasons to be political, though such allegations are difficult to prove.

The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic reduced the UNHCR’s capacity in host countries,[10] leading to a halt in the issuance of asylum cards and slowing the renewal process,[11] creating new challenges, including difficulties obtaining residency permits. These bureaucratic hurdles precipitate more serious issues, such as an increase in detentions due to the expiration of residence permits.

This report concludes with a number of recommendations to make the suffering of Yemenis in host countries more visible to the international community, which may in turn help them to obtain better access to relief.

This is a qualitative study; research relied on interviews via Zoom and various messaging applications with a number of community activists, who are themselves registered as asylum seekers but have not yet been granted refugee status.[12] In the absence of sufficient support, they have created their own initiatives to serve and support refugees. Some interviews were complemented with an online questionnaire and were conducted with four Yemeni community activists in Egypt, three in Ethiopia, two in Somalia, and three in Jordan. The study also relied on an online survey designed to gather first-hand accounts of the UNHCR’s treatment of refugees and the difficulties they face, including its responsiveness to their requests and the provision of protection. The survey reached asylum seekers through community activists also seeking asylum. Eighty-seven respondents were approached and 78 agreed to participate: 69 men, 7 women, and 2 who chose not to identify their gender. Lastly, focus group discussions were held over Zoom with ten Yemeni women asylum seekers in Egypt, and six women and five men in Jordan.

UNHCR offices in Geneva, Egypt, Jordan, and Ethiopia were contacted via email and asked to respond to written questions. Only the Egypt and Ethiopia offices responded to the questions; the Geneva office referred the author to the offices in Egypt and Jordan, and the office in Jordan did not respond. The paper uses data and information published by the UNHCR along with figures from media reports on Yemeni refugees. The study selected Egypt, Jordan, Somalia, Somaliland, and Ethiopia because of the large number of Yemeni refugees residing in these jurisdictions. Coding and analysis of the data focused on three main themes: the process and procedures the UNHCR uses to deal with Yemeni refugees; the challenges facing refugees themselves; and possible reasons for the alleged discrimination they face. The names of refugees, asylum-seekers, and civil society activists have been withheld to protect their safety and privacy.

UNHCR registration procedures vary according to the country in which an asylum application is made. The UN agency has put in place two processes of refugee status recognition which can be collective (prima facie process) or individual. In the case of the individual process, the applicant must deliver a story of personal persecution in his/her country of origin to obtain the right of being a refugee. In Somalia, when an application is submitted to UNHCR, the applicant is required to have proof of identity, such as a passport, ID, or birth certificate. An asylum seeker’s card is granted the same day, and registration is simple for Yemenis – they may even receive some assistance. But it is difficult to obtain refugee status determination (RSD) or resettlement.[13] According to the UNHCR Office in Somalia, the number of Yemeni refugees in the country is about 7,500.[14] In Somaliland alone, there are about 3,000 Yemeni refugees.[15] The UNHCR covers refugees in Somalia and Somaliland, and there is an affiliated Refugee Authority in Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland, which submits information to the UNHCR office in Somalia’s Mogadishu, though its asylum cards bear the emblem of Somaliland.[16] While government agencies do not deal with Somaliland as an independent entity, activists counting refugees record it in their data.[17]

For Yemeni asylum seekers in Ethiopia, applicants must submit an application to the Administration for Refugee and Returnee Affairs, which assesses arriving asylum-seekers, reviews the applications, and submits them to UNHCR. The applicant is interviewed by the ARRA within two days of processing, and by UNHCR within two weeks. The agency then determines whether to grant refugee status.[18] If the asylum application is accepted, the UNHCR will issue an asylum card.[19] According to a UNHCR official in Ethiopia, as of November 2021 there were 2,489 Yemeni refugees in Ethiopia.[20] Community activists put the number higher, between 3,200-4,000.[21]

The largest population of Yemeni refugees is in Jordan. Official estimates put the total at about 13,800,[22] while activists believe the figure is between 14,750 and 15,000.[23] On their arrival, asylum seekers must go to the UNHCR office to register for refugee status and obtain documentation of their application.[24] But according to a Yemeni activist in Jordan, UNHCR registration has been effectively closed to all nationalities except Syrians since the end of 2018.[25], [26]

In Egypt, Yemenis are allowed to register with the UNHCR and submit their asylum applications, according to Saint Andrew Refugee Services.[27] UNHCR documents are then issued, protecting applicants from refoulement and allowing them to receive services. However, in registration interviews, they undergo a process known as an enhanced registration interview, where the UNHCR assesses the conditions or persecution that forced them to flee Yemen, so it can determine whether they have resettlement needs. At a later stage, UNHCR contacts applicants and invites them for two interviews, one for refugee status determination and the other for resettlement needs.[28]

UNHCR spokeswoman Radwa Sharaf puts the number of Yemenis registered with the agency in Egypt at 9,579.[29] Asylum seekers are able to register on the basis of their nationality with a Yemeni passport or ID. Applicants are given a month to return for an initial interview, on the basis of which a yellow “asylum seeker” card is issued.[30] The resettlement process remains very slow – less than one percent of all refugees worldwide are resettled annually, according to Sharaf.[31]

International law includes provisions aimed at the protection of refugees. Article 73 of the Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 stipulates, “Persons… who were considered as stateless persons or refugees… shall be protected persons… in all circumstances and without any adverse distinction.”[32], [33] The 1951 Refugee Convention obliges signatory state parties to protect asylum seekers and deal with them fairly, without discrimination.[34] Some observers see the right to protection and resettlement as self-evident human rights.[35] But refugees are routinely politicized, shaping the policies that govern their treatment with enormous consequences for those seeking refuge.[36]

There are no accurate statistics available, but activists believe very few Yemeni refugees have received resettlement and that there is exceptional disregard for Yemenis, even in cases that require urgent intervention.[37], [38] Though their treatment varies by country, displaced Yemenis contacted by community activists generally described the international humanitarian response, and the work of the UNHCR, as insufficient.

According to two Yemeni activists and asylum seekers in Somalia, no Yemeni refugee has been resettled since 2015.[39] One activist in Somalia alleged that the processing of Yemeni refugees has been stalled for years, and even though there are cases that meet the conditions for resettlement, no action has been taken. The problems refugees face while they wait in the country are numerous.

One refugee in Somaliland stated, “The aid we get is very limited, and there is no response. Many of us cannot return to Yemen because of death threats, some have already had their families killed and their homes blown up. The treatment of Yemenis in Somaliland is very bad in terms of work and living conditions. I’ve been constantly thinking about committing suicide to get [out of this] hell of neglect and marginalization.”[40]

Some blame the UNHCR for their predicament. “We and our rights are completely ignored by the UNHCR, and we are treated with disregard [in terms of] services, not even [receiving] basic rights, such as education, health, protection,” said one refugee.[41] Refugees in Somalia also suffer from persecution and racial profiling by police and gangs. One complained, “there is no security and we are being looted and robbed at gunpoint.”[42]

There is also a language barrier. Refugees say they find it difficult to communicate with the UNHCR and to obtain instructions for filling out their forms because they are only in English and Somali.[43] “As Yemeni activists and [asylum seekers], we have difficulty working because of the language difference, which is a major obstacle to many,” said one activist in Somalia. “I received a death threat because of my work and was asked to stay at home. I informed UNHCR and informed the police, but received no reaction.”[44] Another activist and asylum seeker in Somalia added, “The work is very difficult, apart from the racism that we are subjected to and the cronyism by Somalis and the municipality.”[45]

An activist in Somaliland stated that the office in Hargeisa places Somali refugees who were in Yemen and now allegedly have Yemeni passports onto the lists of Yemeni refugees. Somalis are then allegedly given priority in obtaining services and resettlement, while other Yemeni refugees only receive an asylum card and are not included in the resettlement program. Yemeni refugees receive few to no services, other than the residency provided by the UNHCR card.[46] One activist asylum seeker said he has been treated with neglect and received death threats, and that he held a sit-in and hunger strike in front of the UNHCR office.[47]

“There is no work and no support from UNHCR, we are like the homeless in this country,” said one Yemeni refugee in Somalia.[48] Some small labor projects are available, but they reportedly have little impact on refugee support. Two hundred beneficiaries out of 1,000 are selected and given US$400 to carry out a project. But rent runs as high as $100, so the wages are barely enough to get by. Capacity building and empowerment projects have allegedly been beset with problems, such as broken sewing machines.[49] Yemeni refugees are unlikely to find a job unless they already have a network of acquaintances, which is rarely the case.

Yemeni refugees in Somalia do receive some medical services and educational grants.[50] A small number receive up to US$60 in financial aid, while some families can receive up to US$100.[51]

The experience of Yemeni refugees in Ethiopia is similar to that of Somalia. Some refugees receive financial assistance from UNHCR, though it is not sufficient to cover basic necessities. Aid for families ranges from US$40 to US$100, depending on their size.[52] “We get a monthly salary, but it’s not enough for a half month,” said one refugee.[53]

A former activist and asylum seeker in Ethiopia says that during a four-year period, only four or five Yemeni cases have been resettled, a figure they claim is negligible compared to other nationalities.[54] A number of Yemeni refugees in Ethiopia have been arrested and detained and their passports withheld – this is especially common for those who entered through Somalia. Refugees whose residential permits have expired have had to pay fines; this often happens as a result of their lack of understanding of the rules and regulations, and the Yemeni embassy has been of little help in this regard. Language and cultural differences also pose a major challenge for Yemeni refugees in Ethiopia and have affected their social integration, according to an activist.[55] One refugee complained: “We in Ethiopia suffer a lot, because Ethiopia is not an Arab country, and it is difficult to adapt because of the language difference. It is easy for children, [who] can easily learn the language, and those who have relatives in Ethiopia […] but we are suffering here.”[56]

In August 2016, a number of Yemeni refugees held a protest in front of the local UNHCR office to draw attention to their deteriorating situation, denouncing what they called neglect, marginalization, and denial of their rights, and demanding that the agency justify its decisions on refugee statuses and applications for resettlement.[57]

Yemenis have migrated to East African countries since ancient times, a trend that intensified from the end of the 19th century. Yemenis with mixed heritage, referred to in the Yemeni dialect as Muwalladin, sometimes have family ties in these countries.[58] One 31-year-old respondent settled in Somaliland in 2012, where he was reunited with family members. Facing poor resettlement opportunities in Hargeisa, he moved to Jordan to register with UNHCR and wait for resettlement. The exile of Yemenis is thus sometimes highly fragmented and non-linear and evolves as host countries change their policies.

In Jordan, where living costs are high, services for some Yemeni asylum-seekers include winter assistance and food vouchers worth US$30 per month. Very few are registered refugees and receive monthly assistance of about US$180, which barely covers rent, water, electricity, and basic necessities.[59] Some find jobs, but with very low salaries, as they have no work permits. They often face exploitation at workplaces, do not receive their full salaries, and sometimes face sexual harassment. One activist and asylum seeker in Jordan states, “It is difficult to work in Jordan, [except] to volunteer in an organization or other foundations where we work for a very small fee.”[60] If they apply for work permits, they are required to waive their asylum cards, which leaves them vulnerable to deportation and not eligible for resettlement.[61]

One refugee in Jordan believes that their lack of access to resettlement may be the result of a political act by the Yemeni government and coalition countries to cover up the tragic situation of Yemeni refugees, but it is difficult to substantiate such allegations. He speculated that they do not want Yemen recognized as a war zone, but rather as a series of more locally confined conflicts, which would affect eligibility for resettlement.[62] An activist in Jordan suggested that “the reason why Yemeni refugees are treated as asylum seekers with no priority compared to other nationalities, in terms of resettlement in a third country, is that countries do not see the condition in Yemen as a humanitarian disaster but as a crisis.”[63]

In Jordan, Yemeni refugees also face the threat of refoulement. According to an Amnesty International report, there are government directives to UNHCR not to recognize any refugees other than Syrians, depriving Yemenis of their human rights and putting them at risk of deportation.[64] According to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, “No contracting State shall expel or return a refugee in any manner whatsoever.”[65] But Amnesty International has reported that “authorities took most of the deportation decisions after Yemenis applied for work permits, trying to rectify their immigration status in the country.”[66] Such policies affect huge numbers of people – the organization reports that “as of March 16, Jordan has hosted 13,843 Yemeni refugees and asylum seekers.”[67]

A UNHCR spokesman told Jordanian news outlet Amman Al-Ghad that a number of Yemeni refugees were deported for violating labor and residency laws, and that UNHCR was in contact with the Jordanian government to find solutions.[68] In the meantime, applicants continue to live in limbo. A mother of four seeking asylum said, “I applied to UNHCR three years ago and I am still waiting for a response to accept or reject my application. I am afraid to go out of the house because I don’t have a residency permit.”[69]

An activist and asylum seeker in Egypt says that the registration and resettlement process there has stalled. “The reasons are unclear, because Yemenis do not have access to RSD or protection and resettlement for deserving cases, rather they are promised [these], and years pass by without any change. We always hear staff telling us that Yemenis are not eligible for resettlement and that Western countries refuse to receive them, without giving any further explanation.”[70]

The decision to resettle refugees and migrants is not made by the UNHCR; it is up to individual countries to accept applications.[71] An activist in Egypt claimed: “During the last meeting with the UNHCR and the RSD department staff, we were told that Yemenis in Egypt are unlikely to get RSD, like refugees of other nationalities. They did not stipulate any reason to explain why Yemeni refugees in Egypt are denied resettlement. Clearly, Yemeni refugees are discriminated against.”[72] But the lack of resettlement opportunities holds for all nationalities – fewer than one in a hundred are resettled.

One man said his 22-year-old brother had arrived in Cairo in 2018 and registered with the UNHCR that same year. He suffered from health problems due to a car accident. His brother said that adequate assistance was not forthcoming:

“We used to stand for hours in front of UNHCR and Caritas Internationalis and we used to go back home without getting any assistance. After several attempts, we went to Saint Andrew’s Refugee Services, one of the organizations based in Egypt that provides assistance to refugees and immigrants, which asked us for several tests and reports. We were interviewed several times with a foreign lawyer, and we were referred to a doctor through the organization, who confirmed that my brother’s condition is deteriorating and that his treatment does not exist in Egypt, and [that he] must be resettled for treatment in a specialized center. After four years of neglect, his health problem worsened as a result of the use of many medications, and he began suffering from hepatitis and an enzyme disorder, apart from the deterioration of his mental state.”[73]

His brother said that he ultimately decided to withdraw the application and return to Yemen, “to die… in his mother’s lap.” When he submitted a letter to UNHCR on why he wished his file to be closed, he said he was surprised by the UNHCR’s quick response and the acceptance of the closure of the file within two days. His brother claims that the UNHCR discriminated against him because of his nationality. “Because we hold Yemeni nationality, our file has not been looked at – if my brother was Syrian, Sudanese, or any other nationality, we would have been resettled and provided facilities.”[74]

Another refugee in Egypt decried what he saw as a lack of protection by the UNHCR. “We have rights like others, and we are not satisfied with the manner in which we are dealt with and discriminated against. One of our simplest rights is to get protection, but unfortunately, we are not protected. If we communicate with them, our complaints are ignored. I have had many problems, and I contacted UNHCR and Save the Children and unfortunately, no one provided us with any help.”[75] Another Yemeni refugee in Egypt claimed that someone attempted to kidnap her granddaughter; she said she provided UNHCR with proof of this, but that the agency did not take any action.[76] Another refugee in Egypt cited what they perceived as unfair treatment based on their nationality: “One Eritrean refugee’s son was beaten at school and [they] informed UNHCR, which referred the boy to psychological support and [they] were resettled to the Netherlands. Our suffering, on the other hand, is repeatedly ignored and they look at us as non-human. I am a mother of three who do not go to school and stay at home. [Rent] is expensive and our situation is poor.”[77]

In Egypt, Yemeni refugees receive medical services and scholarships and are allowed to attend public schools. A number of families in Egypt receive food aid according to the number of family members,[78] in addition to winter assistance.[79] But the deterioration in economic and living conditions has led to a rise in the rate of domestic violence, according to activists. Women who are not breadwinners have an even more difficult time, as UNHCR support allegedly does not include many of them, although many have applied for RSD.[80] “Unfortunately, they treat us with contempt and inhumanity,” said one refugee.[81]

The UNHCR reduced its staff by half due to the implementation of Covid-19 restrictions, which prevented refugees from registering or renewing their cards or residence permits. This, in turn, led to residence-related arrests and detentions.[82] On November 22, 2021, a number of Yemeni refugees held a protest in front of the UNHCR office in Cairo, decrying their deteriorating situation and demanding explanations for the agency’s perceived indifference.[83]

The number of questionnaires received was 112. Thirty-four questionnaires were eliminated for not being adequately completed, duplications, or not granting consent. Responses reflected a high dissatisfaction with the treatment and services of the UNHCR, which is more or less uniform across host countries included in this research: Ethiopia, Somalia, Somaliland, Egypt, and Jordan.

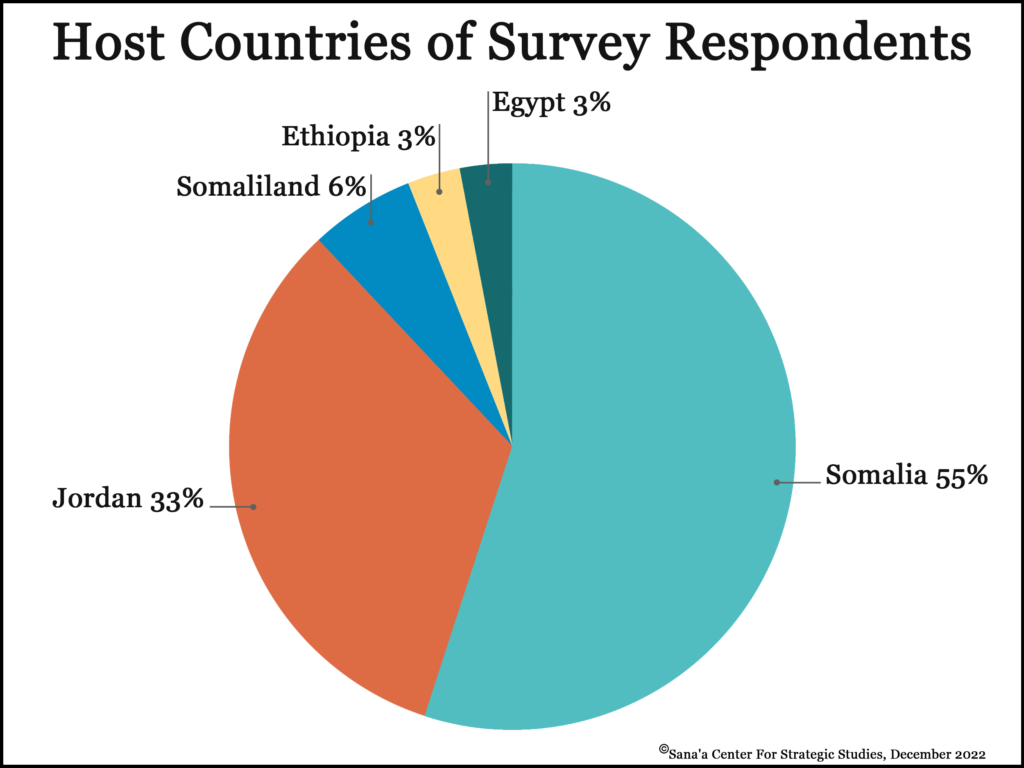

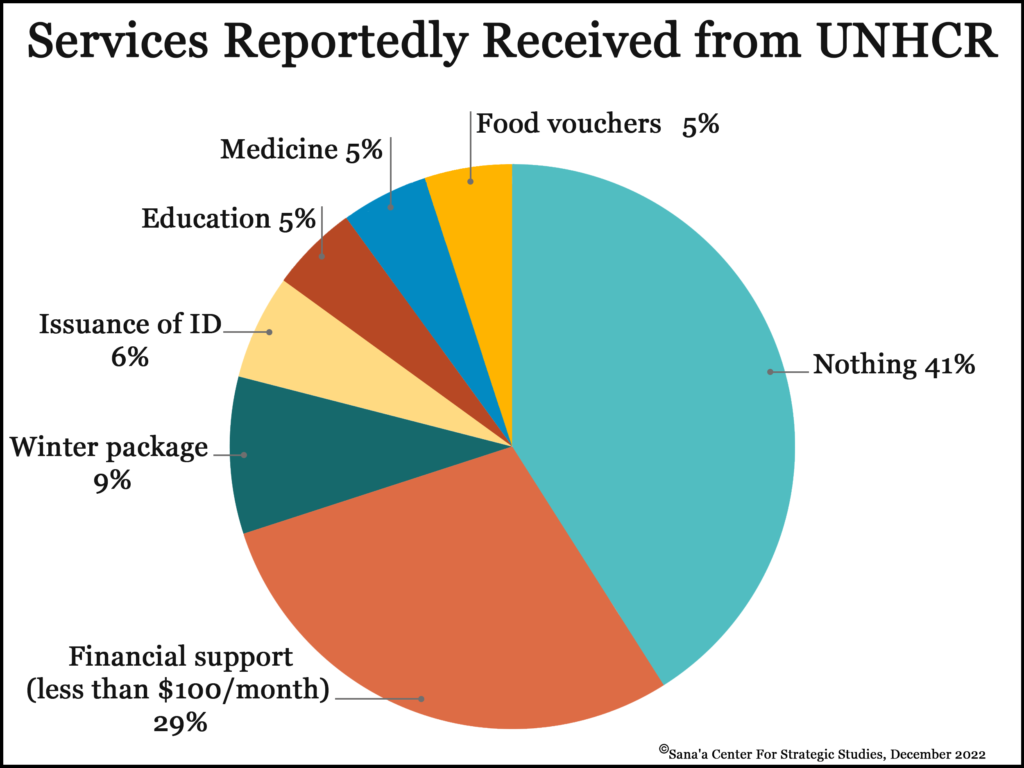

Figure 1.

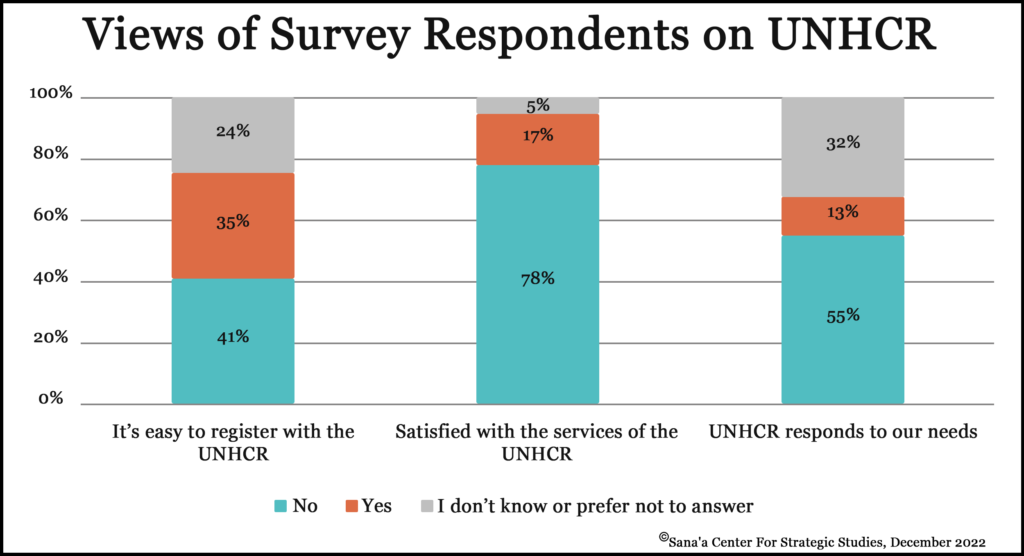

Responses to the question about how difficult it is to register with the UNHCR varied significantly between Jordan and other host countries. In Jordan, 68 percent said that it is difficult to register, while across other host countries only 28 percent said it is difficult to do so. This corresponds with reports that the registration of Yemeni asylum seekers in Jordan has stopped. Eighty-seven percent of Yemeni asylum seekers said they do not receive any support from other informal sources, such as Yemeni or Arab charity organizations or relatives, and half said they were not familiar with the services that the UNHCR offers.

Figure 2.

Data from the survey was analyzed with qualitative data analysis software using inductive coding. The main themes that emerged were:

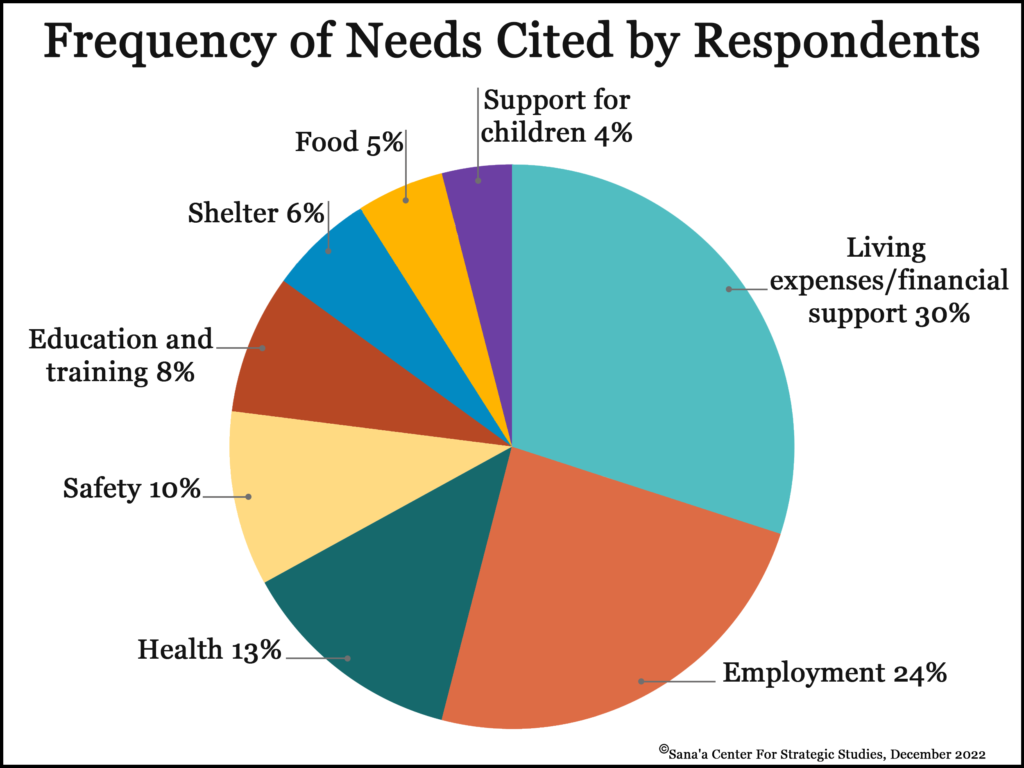

1) Limited access to basic services, including employment or a source of income, shelter, health, safety, food, education, and support for children.

2) Instability, including uncertainty around status and its determination, and the possibility for resettlement, residence permits, and family unification. A constant fear of deportation was also a salient theme.

3) Poor treatment by UNHCR and the host country, including allegations of discrimination and racism, neglect and inaction, corruption and cronyism, and financial extortion.

4) Difficulty in adapting to the new environment, including language barriers, tense relations with the host community, a sense of alienation, and limited understanding of their rights as asylum seekers.

Figure 3.

Respondents in non-Arabic-speaking host countries mentioned that not speaking English or the language of the host country is a barrier for Yemeni asylum seekers in terms of their ability to properly fill out forms, communicate with UNHCR staff, and find employment.

Difficulty finding employment or not being granted a work permit was another main theme. Respondents complained of not being able to obtain work permits or not finding employment opportunities in the host countries.

There were also reports of unsafe environments, with a few respondents referring to violent attacks, armed extortion attempts, having their money or property stolen, or getting beaten up by the police.

Respondents who commented on the services of the UNHCR complained of the unavailability of UNHCR employees. Some also mentioned that Covid-19 made it even more difficult to reach or communicate with UNHCR staff.

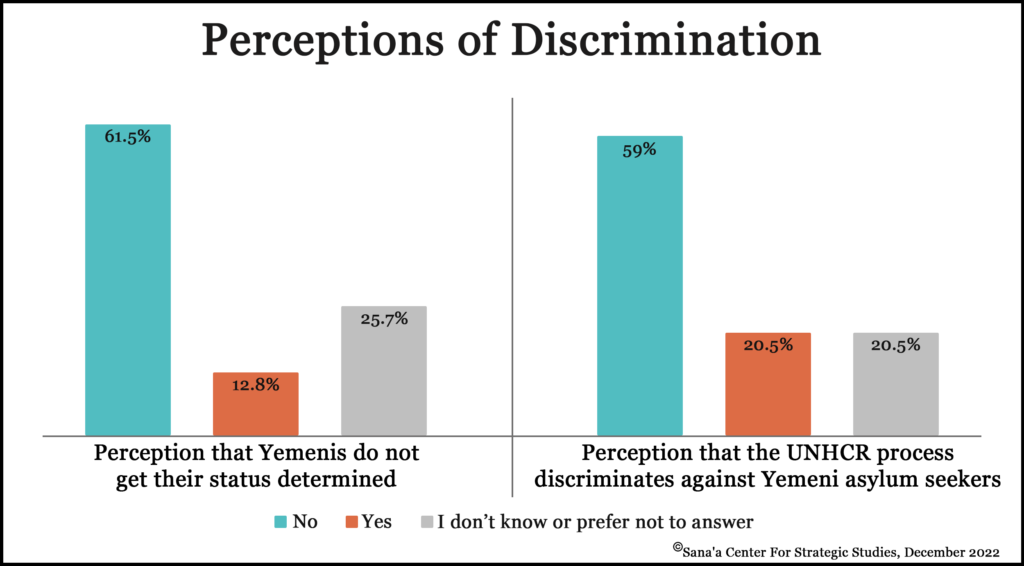

Respondents expressed a high sense of discrimination against them as Yemeni asylum seekers, often comparing themselves with other nationalities, suggesting that it is harder for Yemenis to be recognized as refugees compared to Oromo or Syrian refugees. A few alluded to a notion that states don’t want to recognize Yemenis as refugees because it would acknowledge that Yemen is a warzone, and thus tacitly blame the Arab Coalition for their plight. This was also expressed in interviews with community activists seeking asylum. Although it is difficult to substantiate such claims, they seem to represent a fairly common perception.

Figure 4.

Asked about the services they have received from the UNHCR, 41 percent said they have received nothing, while 29 percent said they received some financial support – with amounts ranging between US$60 to US$70 per month. Some mentioned that they received winter support and, to a lesser extent, other services, such as ID cards, food vouchers, medicine, and education or vocational training.

Figure 5.

Researchers have posited a number of reasons for the alleged differences in how Yemeni refugees are treated. Ahmed Al-Badawi, head of the Egyptian Foundation for Refugee Rights, claimed that the number of Yemeni refugees who have been resettled is negligible. He said resettlement requests by Yemeni refugees are not accepted by foreign countries, due to considerations related to the international community’s profiling of the war as a local conflict. According to Al-Badawi, they have stated that 80 percent of Yemen’s territory is effectively composed of safe zones, where Yemenis can move and settle, contrary to the situation during the civil war in Syria. Al-Badawi suggested that another reason for refusing to resettle Yemenis may include Yemen’s association with terrorism. Al-Badawi also said that incoming funding gives priority to certain nationalities, so Yemenis may get some training but are denied participation in other projects, as the funding is earmarked for other nationalities.[84]

Bogumila Hall, an assistant professor at the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw who conducts research on Yemen, stressed that racism and the association of Yemenis with terrorism are some of the reasons that they are not included in refugee quotas.[85] In a report on Yemenis in Lebanon, a UN source said, “Unfortunately, Yemenis are not listed by the main countries [that accept refugees for resettlement]. Those countries control the scene of resettlement, and politics play a big role in that. Yemen is considered a problem [for] the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. [You] see, Syria exerted a lot of pressure on Europe by the flows of refugees from Turkey, but Yemen is not a nearby problem to such countries. They [will] always work on the problems that internally affect them.”[86]

According to one activist, another reason Yemeni refugees are not given priority is that they are considered the responsibility of the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, which provides the country with support.[87] The lack of recognition of Yemenis as refugees may thus in part be explained by geopolitical interests and deference to regional powers. For their part, Yemeni refugees are generally unaware of why there is so little resettlement when there appear to be cases that meet the criteria.

For their part, UNHCR offices have provided various reasons for the current situation and dissatisfaction among refugees. The UNHCR spokeswoman at the Ethiopia office stated that it was not true that Yemenis were not eligible for resettlement, and that everyone who qualified was eligible, depending on whether there was a sufficient quota by countries offering resettlement and whether those countries accepted certain individuals or not. She also stressed that pursuant to the provisions of the relevant international and national conventions, Yemenis have the right to apply for asylum and be recognized as refugees. She stated that all Yemeni citizens who arrived in Ethiopia as of January 1, 2015, have been granted prima facie recognition as refugees.[88]

Radwa Sharaf, a UNHCR spokeswoman in Egypt, discussed the situation there: “Cases with protection needs are prioritized, and resettlement is one of three sustainable solutions for refugees. UNHCR takes into account the standards of the receiving country. While UNHCR recommends resettlement, it is the countries receiving resettled refugees that make the final decision to accept or reject. In general, only one percent of refugees of all nationalities worldwide are resettled. In addition, the issue of resettlement is governed by a set of complex criteria that must be met to accept the application of a refugee and asylum seeker, which vary from one country to another. The application goes through several stages, including personal interviews to ensure credibility. The role of UNHCR is only to make a ‘recommendation’ or ‘submission’ of cases, but the final decision is made by the competent authorities in the country of resettlement which will receive the refugee.”[89] A UNHCR spokeswoman in Ethiopia confirmed that refugee and resettlement criteria and conditions apply to all nationalities.[90]

Despite assurances from the UNHCR that Yemenis are not treated differently from other refugees and asylum applicants, activists and asylum seekers in all of the host countries studied in this paper allege that their cases have stalled, and that Yemeni refugees have not been provided with sufficient legal and social protection or access to resettlement, including those with health needs and women at risk. They contend that the number of those who have been resettled to date is negligible, and that they face discrimination in the process.

A number of Yemeni refugees prefer to get their residential permits on their passports, despite the high cost, as if they get them on their UNHCR cards, they will not be allowed to travel. Yemeni refugees suffer from deteriorating economic conditions, rising rental prices, a lack of access to employment, and increasing poverty. It is difficult to find jobs, though some are able to work in restaurants, cafes, and shops owned by Yemenis. The scarcity of health care and the lack of educational services are driving many children and young people into an unknown future.

The spread of the Covid-19 pandemic has been a global humanitarian and financial crisis, which has resulted in a deterioration in refugees’ situations. UNHCR’s policies changed due to the implementation of Covid-19 protocols. It became difficult for refugees and asylum seekers to communicate with UNHCR and other organizations due to precautionary measures. Communication and booking appointments took place only by phone, email, or Zoom. Newcomers faced difficulties getting an appointment at which to apply for registration.[91] The outbreak of the pandemic led to the exacerbation of the refugees’ ordeal, as an absence of support led to increased suffering. It also worsened unemployment, as many businesses where refugees worked closed – most had been daily workers in restaurants and shops. Developing countries continue to bear the brunt of refugee crises, as they receive large numbers of refugees into environments where it is difficult to find jobs or high-quality health care. Significant changes are necessary to alleviate the conditions faced by Yemenis and other refugee groups in host countries, and to ensure equitable access to the legal rights afforded them under international law.