On March 26, 2015, Saudi Arabia launched Operation Decisive Storm, which was intended to be a brief air campaign – the Saudis told the US it would take “about six weeks”[1] – to expel the Houthis from Sana’a and reinstate Yemen’s internationally recognized president, Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi. Riyadh’s impulsive rush to war would have disastrous consequences for Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and the broader region, unleashing a cascade of actions and reactions that, like the conflict itself, continues to this day. Al-Qaeda’s control over Mukalla one week after the Saudi air campaign began represented the first substantial repercussion.

Fighters from Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) took control of Mukalla, Yemen’s fifth-largest city and a key port on the southern coast of Hadramawt governorate, on April 2, 2015. For the next 387 days, AQAP would rule over a city of 500,000, amassing millions of dollars in revenue and recruiting hundreds of fighters to its black banner. This was AQAP’s second attempt at holding and administering territory in Yemen. Its first try, in March 2011, during the upheaval of the Arab Spring, had ended in failure when AQAP was forced to withdraw from areas under its control — Ja’ar in the governorate of Abyan and Azzan in Shabwa governorate — leaving behind an exhausted and disillusioned citizenry. But Nasir al-Wuhayshi, AQAP’s commander at the time, a former personal aide to Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan who had studied his decisions and emulated his strategic thinking, believed he had learned a number of lessons from Al-Qaeda’s first failed attempt to rule, and he was ready to try again.

Based on dozens of interviews with witnesses, journalists, human rights activists, government employees and tribal sheikhs in Mukalla and the surrounding area, this is the story of AQAP’s 387 days in power. It starts, as do most stories of Al-Qaeda in Yemen, with a prison break.

They Came Like Ghosts in the Night

The gunfire started after midnight. At first no one thought much of the noise. Interruptions were common in Mukalla that spring. The power was constantly going off, cutting lights and fans, one more nuisance for the city’s half-million residents heading into summer. But within minutes, it became clear that this wasn’t typical celebratory gunfire or a brief firefight. This was something different. This was sustained shooting, gunfire and heavier weapons.

Around 12:50 a.m., a local journalist for Al-Saeeda TV gave up on sleep and, guessing at the rough location of the disturbance, called a source. The shooting sounded like it was coming from the western edge of the city, so she dialed Awad Hatem, the deputy governor, who lived in Fuwwah, on Mukalla’s western outskirts.

I don’t hear anything, the deputy governor said. Next, the journalist tried the commander of the presidential palace guards. He at least could hear the gunfire, but, worryingly, had no idea what it was. Let me call you back, he said. A few minutes later, he did. His message: Al-Qaeda was inside the city.[2]

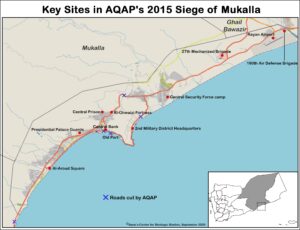

An hour earlier, Al-Qaeda fighters in Toyota Hiluxes and Land Cruisers had gathered at Al-Aroud Square in western Mukalla. Some of the men were masked, some were not, but all were armed. A few residents, more curious than cautious, asked the men what they were up to.

A raid on the central prison in the city was the answer. They’d be quick, the armed men said. In-and-out.[3]

What came next was something different: a well-executed and carefully coordinated sealing of a city. The Al-Qaeda fighters – estimates range from 100 to 400 – split into at least five different groups. Three of these blocked the major roads into the heart of Mukalla — near the local branch of the Central Bank of Yemen, the city’s old port and just northeast of the 2nd Military District’s headquarters. Another group sealed off the coastal road southwest of Al-Aroud Square. The fifth group blocked a key entry from the north, along the road to Al-Ghwaizi Fortress.

Al-Qaeda’s two main bodies of fighters descended on the group’s primary targets: the central prison and the central bank.

Near the central bank in downtown Mukalla, a thunderous explosion woke Saeed al-Batati’s two children.[4] Al-Batati, a stringer for The New York Times, could hear the gunfire coming closer until it seemed to be coming from directly outside his window, as Al-Qaeda fighters exchanged fire with the bank’s guards a few a hundred meters away. An armored vehicle outside the bank exploded after an Al-Qaeda fighter fired a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) at it.

Guards at the bank made a number of distress calls, begging for reinforcements from security forces east of the city as well as those stationed near the port. Neither group would ever reach the bank. Al-Qaeda’s blockade of the roads held and, after an initial clash that resulted in the death of two officers, the Central Security Forces didn’t try again.[5] The guards at the bank didn’t know it yet, but they were on their own.

Hunkered down inside his apartment, Al-Batati’s phone flashed with WhatsApp messages. Local journalists were sending each other photographs of armed gunmen driving through the city in pickups. One message read: “Al-Qaeda freed prisoners from the central prison.”[6]

Freeing Batarfi

Al-Batati’s colleague was correct. Al-Qaeda fighters had streamed toward the prison. There were a number of Al-Qaeda fighters inside, but the most prominent figure was a heavyset 36-year-old who’d let his beard grow out during his nearly four years in prison, named Khaled Batarfi.

Born in Saudi Arabia to a Hadrami family, Batarfi traveled to Afghanistan in 1999, spending eight months at Al-Qaeda’s Farouq Camp near Kandahar.[7] Batarfi returned to Afghanistan a second time shortly before the September 11, 2001, Al-Qaeda attacks on New York and Washington. During the fighting that followed the American invasion of Afghanistan, he eventually made his way over the border to Pakistan and then to Iran, where he was arrested and later deported to Yemen.

The Yemeni government kept him in prison for two years, releasing him in 2004. Batarfi married and had two sons, but by 2008, he had rejoined Yemen’s budding Al-Qaeda affiliate. Batarfi quickly moved up the ranks and in 2010 was named AQAP’s emir in Abyan. However, a few months later, in March 2011, just as AQAP was preparing for its first attempt at administering territory, Batarfi was arrested at a checkpoint outside of Taiz as he attempted to visit his family.[8] He spent more than two years in the Political Security Organization prison in Sana’a before being transferred to Mukalla in late 2013. By April 2015, Batarfi had spent 19 months in Mukalla’s central prison. But now that was about to end, with Al-Qaeda fighters standing outside the prison gates ready to set him free.

The battle for Mukalla’s prison didn’t last long. A well-aimed RPG struck the main guard tower, overlooking the central gate, and that was it. Al-Qaeda gave the guards a choice: They could surrender the prison and leave, or they could fight to the end. The guards handed over the keys, discarded their uniforms, and didn’t look back.[9] Locals later noted that neither the prison director nor the commander of the guards was at the prison when the overnight attack began.

Most reporting on Al-Qaeda’s takeover of Mukalla suggests that 300 prisoners were freed that night, but this is a guess based on the prison’s official capacity of 300 people. Mukalla’s prison, however, was frequently overcrowded. Indeed, a year earlier in 2014, a study conducted by the United States Institute of Peace showed that the prison population of Mukalla’s central prison was actually 483.[10]

One of Batarfi’s first stops after being released was a presidential palace, freshly seized atop a mountain that overlooks the Fuwwah district in the west of the city where he posed for pictures. In one photograph, Batarfi is reclining on an ornate sofa, pink pillow under his elbow, a phone in one hand, rifle in the other. Another photograph shows him treading on the Yemeni flag.[11]

Securing the City

Al-Qaeda fighters moved on the presidential palace and the Central Security Force’s camp after raiding the prison and attacking the bank. At the palace, Al-Qaeda used a booby-trapped car as a battering ram, storming the gates after it exploded and exchanging gunfire with guards inside the palace; the battle ended and the palace was turned over to the attackers after an agreement was reached with the guard commander, Khaled al-Kazimi.[12]

At the Central Security Forces’ camp in Bowaish district east of the city, Al-Qaeda issued an ultimatum to the soldiers inside. They could surrender their weapons and leave, they could fight and die, or they could stay in Mukalla and work with Al-Qaeda to secure and control the city for a monthly salary of 99,000 Yemeni rials (about US$360 at that time), triple the salary of an enlisted soldier.[13] Some chose to leave, others remained behind to work with Al-Qaeda. Armed gunmen affiliated with Al-Qaeda quickly secured the base and took control of its weapons depot, including American-made Humvees.[14] AQAP also seized the radio station and, later, the 27th Mechanized Infantry Brigade base in Al-Riyan, just east of Mukalla.

By sunrise, the extent of Al-Qaeda’s control was clear: The central prison was empty and government soldiers had either disappeared or been incorporated into Al-Qaeda’s ranks. Al-Batati, the New York Times stringer, ventured out of his house briefly on Thursday, for a quick trip to the mosque, but found the streets empty and eerily quiet.[15]

The next day, however, al-Batati listened to residents at Friday prayers describe the militants as “surprisingly friendly and open — different from the AQAP men who had grabbed control in the southern province of Abyan in 2011, and harshly imposed Islamic law.”[16]

Al-Qaeda appeared determined to apply lessons from its previous attempt to hold and administer territory in Yemen. Three years earlier, in 2012, Nasir al-Wuhayshi, the head of AQAP, had written a pair of letters to Abdelmalek Drukdal, his counterpart in North Africa, reflecting on AQAP’s failed first attempt to govern. Make sure the people have electricity and running water, Al-Wuhayshi instructed Drukdal. “Try to win them over through the conveniences of life. It will make them sympathize with us and make them feel that their fate is tied to ours.”[17]

In Mukalla, Al-Wuhayshi took his own advice one step further. Hadrami members of AQAP kept their faces uncovered and directly interacted with residents, while members from outside the governorate remained masked and tried to stay in the background.

At the mosque, Al-Batati overheard one of the armed men tell a resident: “We did not come to plunder or allow others to do so. We need a couple of days to restore order.”[18]

Three years earlier, Al-Wuhayshi had written Drukdal: “Try to avoid enforcing Islamic punishments as much as possible, unless you are forced to do so.”[19]

In Mukalla, Al-Batati saw how Al-Qaeda implemented its new way of administering territory. They didn’t stop people, including women, from walking in the street. They didn’t prevent people from watching football matches or listening to music, and they didn’t fly their famous black flags.[20] “Maybe it was a new form of Al-Qaeda,” he speculated in a post for The New York Times. “Maybe it wasn’t Al-Qaeda at all.”[21]

But Al-Qaeda it was, and on that Friday in early April 2015, the terrorist group controlled Mukalla, the capital of Hadramawt.

Uncomfortable Questions

Perhaps the most persistent and confounding question regarding Al-Qaeda’s takeover of Mukalla is: Why was it so easy? How did a few hundred men in pickups capture a city of 500,000, and the headquarters of the 2nd Military District, effectively seizing control within hours and consolidating it within a few days? Was it a conspiracy, incompetence or something else?

Part of the answer is that Mukalla had a hardened outer shell of military camps and bases, but once inside the city, Al-Qaeda had free range of movement and was quickly able to exert control. If the security cameras inside the city were turned on in the pre-dawn hours of April 2, no one responded to the images they were relaying. Mukalla, like some other cities in Hadramawt, had formed local committees throughout the city to help authorities maintain security and provide services, but had never distributed weapons.

At the same time, the military’s presence had also been reduced in Hadramawt. Yemen’s military in late 2014 and early 2015 was a fractured and fragmented mess in the midst of a series of reforms that never quite took hold. Before that, much of the military’s leadership was from northern governorates and loyal to either former President Ali Abdullah Saleh or General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, a former ally of Saleh who broke with him in March 2011.

In April 2015, there were five military camps in and around Mukalla:

- a Central Security Forces camp commanded by Major General Abd al-Wahhab Sayf al-Waili;

- the 27th Mechanized Brigade, based in Al-Riyan, and commanded by Tawfiq al-Harbi, an Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar loyalist;

- Presidential Palace Guards, who were stationed at the palace, and commanded by Khaled al-Kazimi from Abyan;

- the 190th Air Defense Brigade, based at Al-Riyan and commanded by Husayn Imran, another Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar loyalist; and

- the 2nd Military District headquarters in Khalf, led by Mohsen Nasser.

According to a retired military official, Nasser, the 2nd Military District commander, never issued an order to respond to the Al-Qaeda attack.[22] A coordinated military response could have proven effective, as government military forces easily outnumbered and outgunned the AQAP militants. Instead, Al-Qaeda took a piecemeal approach to conquest, surrounding one base at a time, negotiating with each base’s commander individually, and then moving on to the next target. Each negotiation was different – for instance, Al-Qaeda allowed the soldiers of the 190th Air Brigade to leave with their wages, personal weapons, and 120 bullets each – but all had the same result: surrender.[23]

Local tribes, the only other groups with sufficient men and arms to prevent Al-Qaeda from seizing Mukalla, also failed to take decisive action. Most tribes understood that their territory stopped at the city’s edge and, as a result, they were unwilling to enter Mukalla to confront Al-Qaeda. One tribe, the Nouh, unsuccessfully attempted to break Al-Qaeda’s siege of the 27th Mechanized Brigade east of the city.

Managing the City: By God, We Rule

In 2011, when AQAP took over parts of Abyan and Shabwa, it introduced itself as Ansar al-Shariah. It was a calculated choice. Nasir al-Wuhayshi, the head of AQAP, knew that Al-Qaeda’s brand was unpopular, bloodied by the carnage in Iraq and elsewhere, and he wanted a fresh start in Yemen. As Adil al-Abab, an AQAP cleric, explained in an interview: “The name Ansar al-Shariah is what we use to introduce ourselves in areas where we work to tell people about our work and goals.”[24]

In 2011, Al-Qaeda wanted to play up two things: its adherence to God’s law and its ability to provide services such as electricity and sewage lines. But its interpretation and implementation of shariah, particularly mandatory punishments known as hudud, quickly overshadowed everything else it was trying to do, a fact Al-Wuhayshi lamented in his letters to Drukdal a year later.

A year after taking power in Abyan and Shabwa, AQAP was forced to retreat. Looking back on the experience, Al-Wuhayshi realized that AQAP had dangerously miscalculated on a number of issues, including the group’s new name. AQAP had played up the group’s religious credentials. But it hadn’t worked. After all, as Al-Wuhayshi wrote Drukdal in 2012: “You can’t beat people for drinking alcohol when they don’t even know the basics of how to pray.”[25]

Three years later, in Mukalla, Al-Wuhayshi tried a different approach. This time Al-Qaeda fighters introduced themselves as “Sons of Hadramawt.”[26] Instead of playing up their religious credentials, Al-Qaeda played up its local connections. They wanted to show the people of Mukalla that they were their sons and brothers, their uncles and cousins. Which is why Al-Wuhayshi, who was from Abyan, instructed fighters from Hadramawt to keep their faces uncovered while those from other areas or countries kept their faces masked, at least initially. As Abd al-Hakim bin Mahfood told the journalist Al-Batati a few months later, the fighters were “from famous Hadrami families.”[27]

Al-Wuhayshi also instructed his men not to raise Al-Qaeda’s famous black flag,[28] or even announce that they had captured Mukalla. Their story was that they didn’t “control Mukalla in their capacity as members of Al-Qaeda,” but rather as “Sons of Hadramawt.”[29] It was a semantic fig leaf, but one Al-Wuhayshi thought might allow AQAP to succeed in Mukalla where they had failed in Abyan. Part of AQAP’s insistence on being known as the Sons of Hadramawt may also have been, as the International Crisis Group suggested, an effort to avoid being targeted by US drone or air strikes.[30]

AQAP, or the Sons of Hadramawt as they were calling themselves, also announced that they weren’t in Mukalla to rule but rather to protect the city from a potential Houthi offensive.[31] Weeks earlier, Houthi forces, aided by Yemeni troops loyal to former President Saleh, had pushed into Aden. In the early Spring of 2015, just as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates were beginning the direct regional military intervention, some in Hadramawt worried that the Houthis would push east along the coast from Aden toward Mukalla in a bid to control the entire country. This, AQAP announced from the mosque loudspeakers on April 3, is why they had entered the city.[32] It would be the Sons of Hadramawt, not the Yemeni government’s military or security services, who would defend Mukalla from a Houthi offensive.

Hadramawt National Council

A few days after solidifying its control over Mukalla, Al-Qaeda met with local leaders to discuss their plans for moving forward.[33] Batarfi, who emerged as AQAP’s figurehead in Mukalla after being freed from prison, chaired the meeting.[34] Batarfi stressed what Al-Qaeda had announced from mosque loudspeakers on the previous Friday: The group had no desire to rule Mukalla, it only wanted to protect the city from the Houthis.[35]

Batarfi informed local leaders that Al-Qaeda was willing to allow them and local religious leaders to choose a council from among the people of Hadramawt to manage local government institutions.[36] On April 13, that is exactly what happened. Local leaders, under the direction of Omar al-Jaidi bin Shakl, a tribal figure affiliated with Islah, and Abd al-Hakim Mahfouz, the head of the Al-Hikma Al-Yamania Association for Charity, a religious charitable society, formed a council to govern and administer most of the city’s services, including government institutions, water services, electricity and fuel.[37] (Interestingly, the Hadi-appointed governor of Hadramawt, Adel Bahumaid, remained in Mukalla during the initial days of Al-Qaeda’s takeover and was later allowed to depart the city for Riyadh.[38]) Batarfi and Al-Qaeda, however, maintained the authority to form military councils and oversee the defense of the city.[39] The Council of Sunni Scholars, a local group of religious figures in Hadramawt, witnessed and affirmed the agreement.[40]

The agreement allowed AQAP to do two things. First, it could avoid the blame for any missteps in local governance by passing the buck to the supposedly independent council. This meant that AQAP could sidestep some of the administrative issues that had hobbled its efforts in Abyan in 2011. The flip side of that was that anytime Al-Qaeda wanted to take credit for a public service, such as repairing a sewer line or expanding the electrical grid, it could directly claim credit both locally and throughout the country via social media channels. At the same time, the existence of the council served as intermediary between AQAP and outside actors, such as Hadi’s government-in-exile, Saudi Arabia and, perhaps most importantly, oil companies. Each of these could use the cover of the Hadramawt National Council to claim it was not dealing with Al-Qaeda. Indeed, in late April 2015, a delegation from the HNC, led by Bin Shakl, traveled to Riyadh to meet with President Hadi.[41]

But on the ground in Mukalla, there was little doubt as to who was in charge. As one resident told the International Crisis Group in April 2015: “The council (HNC) is widely viewed as a front to legitimize AQAP’s hold on power.” Still, the resident went on, “locals see it as an acceptable way to deal with the outside world.”[42]

Al-Wuhayshi’s Death and AQAP’s Change in Course

One country that did not see it that way was the United States. On April 22, less than three weeks after Al-Qaeda entered Mukalla, the US carried out a drone strike in Mukalla that killed Muhannad Ghallab, AQAP’s spokesman.[43] Some weeks later, on June 12, another US drone strike killed Al-Wuhayshi, the architect of the group’s velvet-gloved approach to ruling Mukalla.[44]

Al-Wuhayshi was succeeded by Qassim al-Raymi, a prominent commander within the organization. Like Al-Wuhayshi, Al-Raymi had spent years in Afghanistan prior to September 11 and was part of the February 2006 Al-Qaeda prison break, which allowed the organization to reconstitute itself in Yemen. But unlike Al-Wuhayshi, Al-Raymi was not a particularly subtle or innovative thinker. In Afghanistan, Al-Wuhayshi had been hand-picked and groomed by Bin Laden; Al-Raymi had been an instructor in an Al-Qaeda training camp. Indeed, Al-Raymi’s first position within AQAP as a military commander perfectly suited his skills as a brave but brash and frequently hotheaded fighter.

Within a week of Al-Wuhayshi’s death, AQAP had killed two Saudi members of the organization on allegations that they were working as spies for the US and Saudi Arabia.[45] The bodies of both men were strapped to crude crosses and hung off the bridge in downtown Mukalla.

As the drone strikes mounted – AQAP lost Nasr al-Ansi, Ibrahim al-Rubaysh, and Mamoun Hatem, among others[46] – so, too, did Al-Qaeda’s heavy-handed response. Initially, in keeping with Al-Wuhayshi’s lessons-learned approach, AQAP had charted a careful and conciliatory course, even putting out a statement in April denying rumors that it was “planning to ban musical parties or men from wearing shorts.”[47] In Al-Wuhayshi’s last public appearance before he was killed in a drone strike, he said that in a time of war it is permissible to limit the practice of hudud.[48] But that attitude did not survive his death. AQAP fighters were being killed, and the group cracked down.

AQAP established the Hisbah, or the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice.[49] Its enforcers roamed the streets in cars they had stolen during their entry into Mukalla, intimidating people, looting and making sure that unmarried men and women were not mixing.[50] Women’s faces on advertisements were blacked out, and prayer advice appeared on bridges.[51] By late 2015, the hudud punishments that Al-Wuhayshi had once warned against implementing were being routinely enforced. A woman was stoned to death for adultery, other women were killed as accused witches, men were publicly flogged, and journalists, radio presenters, and opposition figures were detained or killed.[52]

Hearts and Minds; Money and Electricity

AQAP’s attempt to win over Mukalla’s citizens with competence and cash followed a similar trajectory: an initial period of success followed by deep disillusionment. AQAP-affiliated jurists quickly worked through an extensive backlog of cases in Mukalla’s court systems. For citizens who were used to a corrupt and slow moving system, plagued by nepotism and secret deals, this was a welcome change.[53]

As in Abyan in 2011, AQAP also prioritized service provision. Within days of taking over, AQAP asked employees at the electrical company to return to work and to provide a written list of what they needed to improve production and service. Al-Wuhayshi tapped Abu Anas al-Sanani, a recent graduate of the engineering department at Aden University, to oversee electricity output. Al-Sanani adjusted the pricing system, eliminating tariffs that had often caused spikes in pricing and infuriated locals. AQAP used the Hadramawt National Council to pump an estimated US$2.79 million into the electrical infrastructure in Mukalla for salaries, new transformers and replacement networks.[54] The militants also threatened managers at the utility if they did not meet performance benchmarks, which dramatically reduced corruption and staff absenteeism.[55] According to Mahfouz, secretary general of the HNC, who spoke to Al-Jazeera in September 2015, AQAP had done such a good job expanding the electrical network in Mukalla that the city was prepared to receive “150,000 displaced people from Aden and other provinces,” who were fleeing the fighting between the Houthis and the Saudi-led coalition.[56]

Much like the Houthis in Sana’a, AQAP didn’t try to uproot the entire system, but rather placed one of their men in each ministry and company to work with and oversee the director.[57] It was an awkward working arrangement but, at least initially, it produced results.

AQAP repaired some roads and patched up the sewage system, which the group then highlighted and took credit for in professionally produced videos that were distributed locally and uploaded online. Members delivered medical supplies and equipment to hospitals in the name of Ansar al-Shariah, while interviewing hospital administrators who publicly thanked Al-Qaeda for providing what the government could not.[58] The group abolished taxes and, with some of the money it had gained from looting the central bank, promised to repay back taxes that locals had already paid. Elisabeth Kendall, a scholar at Oxford University, told Reuters that this was Al-Qaeda’s “Robin Hood strategy.”[59]

AQAP also funded its public-facing administrative council, the Hadramawt National Council. According to the HNC’s Bin Mahfood, Al-Qaeda initially distributed $3.7 million,[60] much of which apparently came from the looting of Mukalla’s central bank branch. A Reuters investigation quoted two unidentified Yemeni security officials as saying AQAP had stolen an estimated $100 million from the bank.[61] But as with any numbers connected to Al-Qaeda, fidelity is nearly impossible to ascertain.

During its time ruling Mukalla, AQAP had three main streams of revenue: the initial cash from the central bank, money from extorting oil and phone companies and customs fees on goods and oil flowing through the port at Mukalla.[62] By far the largest of these three streams was the revenue associated with the port, with an official in Yemen’s transport ministry estimating to Reuters in 2016 AQAP’s revenue at about $2 million a day.[63] This would put AQAP’s earnings just from the port at about $774 million; add in the estimated $100 million from the central bank, and a few million in extortion fees and the total is nearing an astronomical and improbable $900 million. According to one Yemeni official, who spoke to Reuters in 2016, even $100 million would be enough to fund the organization for “at least another ten years.”[64]

This raises two related questions: How much money did AQAP actually make during the 387 days it ruled Mukalla and what has it done with that money?

AQAP made a lot of money in Mukalla, and it spent a lot of money in Mukalla. Salaries for new fighters were about $200 per month, compared to the $140-150 a month for a regular Yemeni soldier.[65] Skilled technicians did even better, and some journalists were promised $900 a month for working on websites that serve the organization.[66] But even if the estimates of AQAP’s cash intake are wrong by a factor of 10, the organization should still have some money left from its time in Mukalla. The AQAP of 2020, however, does not look like an organization that is flush with cash. The group seems at its weakest point since it was formed in 2009, riven by backbiting and petty jealousies that have started to slip into the public sphere.[67]

Part of the answer to the mystery of the money might be that Al-Qaeda lost significant funds in its withdrawal from Mukalla. A US airstrike in 2015, in one notable example, is believed to have incinerated $41 million in cash.[68] But perhaps more can be explained by simple corruption.

When AQAP moved into Mukalla in April 2015, it quickly changed the policy on shipping fees into the port of Mukalla, which is Yemen’s third-largest port. AQAP lowered the fees to entice wary companies and, when fighting in Aden made it too dangerous for ships to enter, it presented Mukalla as an attractive and cheap alternative.[69] As its rule continued, AQAP officials started taking bribes from local merchants in exchange for import privileges. Much of this money appeared to go into individual fighters’ pockets instead of into the group’s coffers. For example, the family of Ghalib al-Qu’aiti, who was known as Abu Hajar, an AQAP spokesman who worked at the port until he was killed there in a US drone strike, appeared to vastly increase their personal wealth during 2015-16, including the purchase of real estate in Hadramawt.[70]

As the evidence of corruption grew, and as the hudud punishments increased, the residents of Mukalla had enough. On October 12, more than a hundred of them publicly protested AQAP’s corruption and continued rule.[71] Marching through Mukalla’s streets, the crowd chanted: “No Al-Qaeda after today. Get out.”[72]

AQAP would remain in Mukalla for six more months, but the writing was on the wall.

And Then They Were Gone

On April 22, 2016, as Saudi and Emirati-backed fighters massed on the eastern edge of Mukalla, AQAP released a statement asking local residents not to join the coalition forces.[73] Drawing on what it claimed was its record of good governance, AQAP asked the people it had ruled for the past year to continue to stand with the group in its hour of need. As Kendall, the Oxford scholar, said, “the statement read more like a plea than a threat.”[74]

Publicly, AQAP claimed it was ready to fight to defend the city that had been the source of so much cash over the past year. But behind the scenes something else was happening. According to The Associated Press, a tribal sheikh was shuttling between AQAP leaders in Mukalla and Emirati officials in Aden in an effort to seal a deal that would spare Mukalla by allowing Al-Qaeda fighters to exit the city unharmed.[75]

Both sides had leverage, and both had something the other wanted. AQAP controlled the city and, if forced to fight, it could essentially hold Mukalla hostage, necessitating massive bombing operations that would likely destroy a city the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia wanted to preserve. But it didn’t want to fight for Mukalla, not really. It preferred a negotiated withdrawal, something similar to what happened in 2012 when AQAP pulled out of the cities it held in Abyan.

For its part, the UAE would prefer a deal as well. But just in case that wasn’t feasible, it had slowly been preparing fighters from among tribes in Hadramawt to be ready for combat action. In late 2015, the UAE established a training camp in Rumah, about 600 kilometers east of Mukalla. The camp was named Al-Khalediya camp after its tribal host, Sheikh Khaled al-Manhali. Within months, the UAE had recruited, trained, and equipped 3,000 men, which would form the initial nucleus of what would become the Hadrami Elite Forces.[76] In early 2016, a number of tribal sheikhs and militia leaders met in the area of Sharoura on the Saudi border to devise a military plan for expelling AQAP from Mukalla,[77] but the UAE, like AQAP itself, preferred a negotiated withdrawal.

Eventually that is exactly what happened. AQAP fighters were guaranteed a safe route out of the city, and allowed to keep all the weapons and money they had obtained from their time in Mukalla.[78] One tribal leader, who wasn’t privy to information about the deal, later told The Associated Press: “Coalition fighter jets and US drones were idle. I was wondering why they didn’t strike them.”[79]

Two days later, on April 24, the Hadrami Elite Forces moved into Mukalla. Saudi media initially claimed that 800 Al-Qaeda fighters were killed in the fighting.[80] But that was a lie. As The New York Times reported, “hardly a shot was fired.”[81] A local journalist told The Associated Press the same thing: “We woke up one day and Al-Qaeda had vanished without a fight.”[82] AQAP drove west out of the city along the same roads that its fighters had used to enter Mukalla a year earlier.[83] As it had done in Abyan in 2012, AQAP tried to claim the moral high ground,[84] explaining in a statement: “We are only withdrawing to prevent the enemy from taking the battle to your homes, markets, roads, and mosques.”[85] After 387 days, Al-Qaeda’s time in control of Mukalla was at an end.

This paper was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies with the Oxford Research Group, as part of the Reshaping the Process: Yemen program.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Oxford Research Group (ORG) is an independent organization that has been influential for nearly four decades in pioneering new, more strategic approaches to security and peacebuilding. Founded in 1982, ORG continues to pursue cutting-edge research and advocacy in the United Kingdom and abroad while managing innovative peacebuilding projects in several Middle Eastern countries.

Endnotes

- “U.S. Policy and the War in Yemen,” Brookings Institution, recorded remarks, October 25, 2018. https://www.brookings.edu/events/u-s-policy-and-the-war-in-yemen/

- Interview with a correspondent in Mukalla present during AQAP’s seizure of the city, August 2019.

- Several interviews with residents in the area of Fuwwah and with journalists who were present there at the time of these developments, July 2019.

- Saeed al-Batati, “When Al-Qaeda Stormed My City: Reporter’s Notebook,” The New York Times, April 10, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/times-insider/2015/04/10/when-al-qaeda-stormed-my-city-reporters-notebook/

- Interviews with citizens who witnessed Al-Qaeda’s entry to Mukalla, July 2019; Ibid.

- Al-Batati, “When Al-Qaeda Stormed My City.”

- Gregory D. Johnsen, “Khalid Batarfi and the Future of AQAP,” Lawfare, March 22, 2020, https://www.lawfareblog.com/khalid-batarfi-and-future-aqap

- “Khaled Batarfi, Al-Qaeda commander, arrested [AR],” 26th of September, March 17, 2011. https://www.26sep.net/nprint.php?lng=arabic&sid=72181

- Interview with a resident of Ad-Dees, where the Central Prison in Mukalla is located, who watched the guards withdraw, July 2019.

- “Fiona Mangin with Erica Gaston,” Prisons in Yemen, United States Institute of Peace, March 2015, 51, Table A1, https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/PW106-Prisons-in-Yemen.pdf

- See, for example, “A picture of Khaled Batarfi, one of the leaders of Al-Qaida, being circulated treading on the Yemeni flag at the presidential palace in Mukalla [AR],” CNN Arabic, April 4, 2015, https://arabic.cnn.com/middleeast/2015/04/04/aqap-leader-inside-presidential-palace-southern-yemen

- “Al-Qaeda frees 300 prisoners after attacking Mukalla prison [AR],” Al-Jazeera, April 2, 2015,

- A soldier’s salary was around 33,000 Yemeni rials, about US$120 according to the exchange rate at the time. By tripling it, Al-Qaeda attracted poor soldiers.

- Saeed al-Batati and Kareem Fahim, “Affiliate of Al-Qaeda Seize Major Yemeni City, Driving out the Military,” The New York Times, April 3, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/04/world/middleeast/al-qaeda-al-mukalla-yemen.html

- Al-Batati, “When Al-Qaeda Stormed My City.”

- Al-Batati, “When Al-Qaeda Stormed My City.”

- Rukmini Callimachi, “Yemen Terror Boss Left Blueprint for Waging Jihad,” The Associated Press, August 13, 2013, https://www.pulitzer.org/files/2014/international-reporting/callimachi/08callimachi2014.pdf

- Al-Batati, “When Al-Qaeda Stormed My City.”

- Callimachi, “Yemen Terror Boss Left Blueprint for Waging Jihad.”

- Al-Batati, “When Al-Qaeda Stormed My City.”

- Al-Batati, “When Al-Qaeda Stormed My City.”

- Interview with a retired military figure in Hadramawt, July 2019.

- Interview with a Hadrami tribal figure who lived in the city during these developments, July 2019.

- Quoted in Aaron Zelin, “Know Your Ansar al-Sharia,” Foreign Policy, September 21, 2012. https://foreignpolicy.com/2012/09/21/know-your-ansar-al-sharia/

- Callimachi, “Yemen Terror Boss Left Blueprint for Waging Jihad.”

- Saeed al-Batati, “The Truth Behind Al-Qaeda’s Takeover of Mukalla: An Interview with Abd al-Hakim Bin Mahfood,” Al-Jazeera, September 16, 2015, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/09/yemen-truth-al-qaeda-takeover-mukalla-150914101527567.html

- Al-Batati, “The Truth Behind Al-Qaeda’s Takeover of Mukalla.”

- “Yemen’s Al-Qaeda: Expanding the Base,” International Crisis Group, February 2, 2017, p.11, https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/174-yemen-s-al-qaeda-expanding-the-base.pdf

- Al-Batati, “The Truth Behind Al-Qaeda’s Takeover of Mukalla.”

- “Yemen’s Al-Qaeda: Expanding the Base,” p. 11.

- Interview with a civil activist from Mukalla, 2019.

- Sanad Ba Yaachout, “Al-Qaeda leader Batarfi: We have taken great steps in the process of handing over the city of Mukalla to the National Council, and there is no dispute with Belaidi [AR],” Hadarm, September 4, 2015, http://www.hadarem.com/index.php?ac=3&no=17096

- Joana Cook, “Their Fate is Tied to Ours: Assessing AQAP Governance and Security Implications in Yemen,” International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, 2019, https://icsr.info/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/ICSR-Report-Their-Fate-is-Tied-to-Ours-Assessing-AQAP-Governance-and-Implications-for-Security-in-Yemen.pdf

- Ba Yaachout, “Al-Qaeda leader Batarfi: We have taken great steps…” http://hadarem.com/m/index.php?ac=3&no=17096

- Ibid.

- Al-Batati, “The Truth Behind Al-Qaeda’s Takeover of Mukalla.”

- Al-Batati, “The Truth Behind Al-Qaeda’s Takeover of Mukalla.”

- Ibid.

- Asmaa al-Gabri, “The Hadrami National Council strongly supports the military operations of the coalition forces [AR],” Asharq Al-Awsat, May 29, 2015, https://aawsat.com/home/article/371421/

- Al-Gabri, “The Hadrami National Council strongly supports the military operations of the coalition forces.”See also, Al-Batati, “The Truth Behind Al-Qaeda’s Takeover of Mukalla.”

- Al-Batati, “The Truth Behind Al-Qaeda’s Takeover of Mukalla.” See also, Cook, “Their Fate is tied to Ours,” p. 20.

- “Yemen’s Al-Qaeda: Expanding the Base,” International Crisis Group, p. 11.

- Aiysha Amr, “How Al-Qaeda Rules in Yemen,” Foreign Affairs, October 28, 2015. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/yemen/2015-10-28/how-al-qaeda-rules-yemen

- Dana Bash, “Top Al-Qaeda leader reported killed in Yemen,” CNN, June 16, 2015. https://edition.cnn.com/2015/06/15/middleeast/yemen-aqap-leader-killed/index.html

- Mohammed Mukhashaf, “Al-Qaeda kills two Saudis accused of spying for America: residents,” Reuters, June 17, 2015. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-qaeda/al-qaeda-kills-two-saudis-accused-of-spying-for-america-residents-idUSKBN0OX11Q20150617?feedType=RSS&feedName=worldNews

- Amr, “How Al-Qaeda Rules in Yemen.”

- Amr, “How Al-Qaeda Rules in Yemen.”

- Amr, “How Al-Qaeda Rules in Yemen.”

- Hisbah is a religious term that grants every Muslim the right to object to a behavior practiced by an individual or a community because he or she believes it opposes the teachings of Islam.

- Interview with the detainee’s sister who narrated her story and how segregating between the sexes was one of the organization’s vital goals, especially after seizing the city, September 2019.

- Amr, “How Al-Qaeda Rules in Yemen.”

- Bel Trew, “Mukalla: Life after Al-Qaedaal-Qaeda,” The Independent, August 17, 2018. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/mukalla-yemen-al-qaeda-civil-war-before-after-jihadi-terror-group-a8495636.html; Amr, “How Al-Qaedaal-Qaeda Rules in Yemen;” and Cook, “Their Fate is tied to Ours,.” p. 21.

- Interview with a rights activist in Mukalla with ties to lawyers who dealt with these courts, August 2019.

- Al-Batati, “The Truth Behind Al-Qaeda’s Takeover of Mukalla.”

- Interview in Mukalla with a local journalist, September 2018

- Ibid.

- Interview with a source at the electricity company in Mukalla, July 2019.

- Yara Bayoumy, Noah Browning and Mohammed Ghobari, “How Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen has made Al-Qaeda stronger — and richer,” Reuters, April 8, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/yemen-aqap/

- Ibid.

- Al-Batati, “The Truth Behind Al-Qaeda’s Takeover of Mukalla.”

- Bayoumy, Browning, and Ghobari, “How Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen has made Al-Qaeda stronger and richer.”

- Bayoumy, Browning, and Ghobari, “How Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen has made Al-Qaedaal-Qaeda stronger and richer.”

- Bayoumy, Browning, and Ghobari, “How Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen has made Al-Qaeda stronger and richer.” See also, Hussam Radman, Al-Qaeda’s Strategic Retreat in Yemen, Sana’a Center, April 29, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7306

- Bayoumy, Browning, and Ghobari, “How Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen has made Al-Qaeda stronger and richer.”

- “Yemen’s Al-Qaeda: Expanding the Base,” International Crisis Group, p. 17.

- Interview with a journalist from Ash Shihr city, which was under Al-Qaeda control, who said he refused an offer for such work despite the financial temptation. Interview date is being withheld at the source’s request for security reasons.

- Nahad al-Jariri, “Al-Qaeda in Yemen asks al-Zawahiri to Intervene in Internal Dispute [AR],” Akhbar Alaan, April 26, 2020, https://www.akhbaralaan.net/news/arab-world/2020/04/26/

- “Yemen’s Al-Qaeda: Expanding the Base,” International Crisis Group, p. 17.

- Interview with lawyer from Mukalla, July 2019. Information verified by more than one source who followed up on the policies of the organization in Mukalla.

- Interview with a Mukalla resident close to the family of Al-Quaiti, July 2019.

- Trew, “Mukalla: Life after Al-Qaeda;” Cook “Their Fate is Tied to Ours.”

- Amr, “How Al-Qaeda Rules in Yemen.”

- Elisabeth Kendall, “How can Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula be defeated?” The Washington Post, May 3, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/05/03/how-can-al-qaeda-in-the-arabian-peninsula-be-defeated/

- Ibid.

- Maggie Michael, Trish Wilson, and Lee Keath, “Yemen: US Allies Spin Deals with al-Qaida in War on Rebels,” The Associated Press, August 6, 2018, https://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/yemen-us-allies-spin-deals-al-qaida-war-rebels

- Interview with Sheikh Khalid al-Kuthairi, a prominent tribal figure from Hadramawt, July 2019.

- Ibid.

- Michael, Wilson, Keath, “Yemen: US Allies Spin Deals with al-Qaida in War on Rebels.”

- Ibid.

- “Saudi Coalition Claims it killed 800 Al-Qaeda fighters in Yemen,” Agence France-Presse, April 25, 2016, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/04/25/saudi-coalition-claims-it-killed-800-al-qaeda-fighters-in-yemen/ See also, “Coalition says it seized control over major port, 800 Al-Qaeda members killed in Yemen, BBC Arabic, April 25, 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20160810091415/http://www.bbc.com/arabic/middleeast/2016/04/160425_yemen_mukalla_qaeda

- Saeed al-Batati, Karim Fahim, Eric Schmitt, “Yemeni Troops, backed by United Arab Emirates, retake city from Al-Qaeda,” The New York Times, April 24, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/25/world/middleeast/yemeni-troops-backed-by-united-arab-emirates-take-city-from-al-qaeda.html?_r=0&auth=login-email&login=email&ref=middleeast

- Michael, Wilson, Keath, “Yemen: US Allies Spin Deals with al-Qaida in War on Rebels.”

- Interview with a journalist from Shabwa who monitored AQAP convoys’ withdrawal from Mukalla and entry into Shabwa, July 2019; Interview with a prominent tribal figure from Hadramawt, July 2019.

- Kendall, “How can Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula be defeated?”

- Al-Ahmar announces purging Mukalla of Al-Qaeda, and Al-Qaeda confirms, Al-Khaleej Online, April 30, 2016, https://alkhaleejonline.net/سياسة/الأحمر-يعلن-تطهير-المكلا-اليمنية-من-القاعدة-والأخيرة-تؤكد

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية