Executive Summary

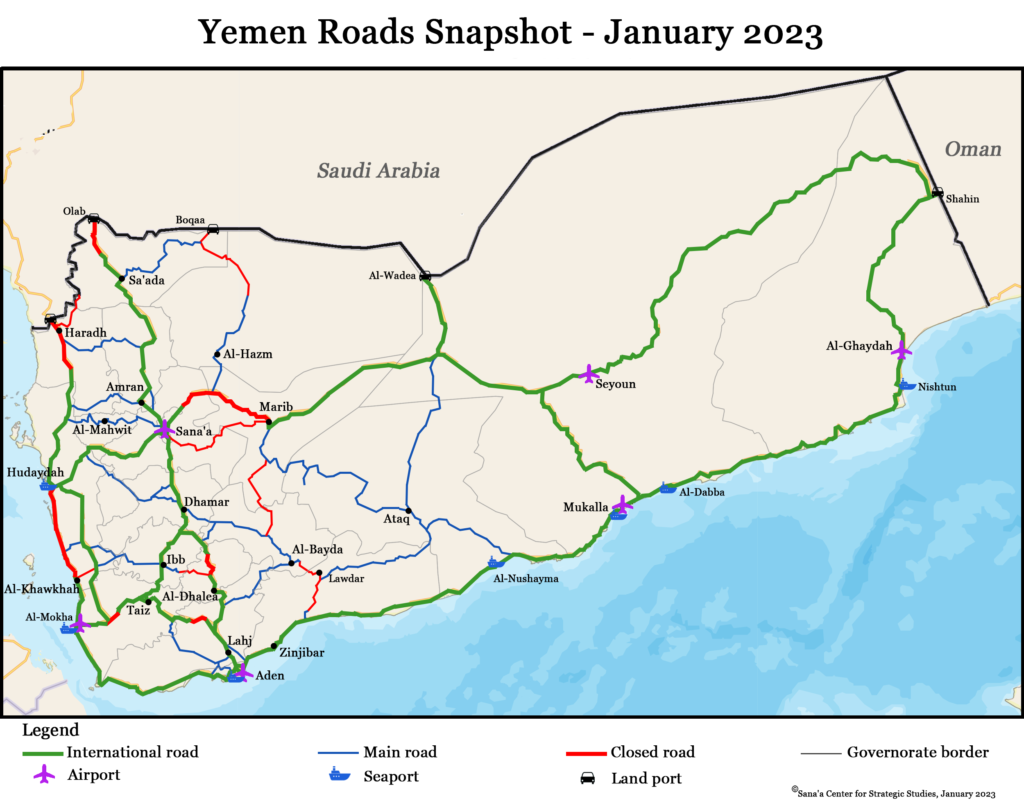

Yemen’s limited network of paved highways in the densely-populated western third of the country has been battered and weaponized during eight years of war. At least 100 bridges and approximately one-third of Yemen’s paved roads (between 5,000-6,000 kilometers) have been destroyed in military operations, according to estimates from Houthi authorities in Sana’a and the internationally recognized government in Aden. The warring parties have closed main highways due to their proximity to the frontlines, damages sustained during clashes, or to deprive opponents of access to strategic areas. Roads that have not been closed for military reasons have not been maintained since the start of the war, leaving many of them unfit for travel. As a result, motorists are forced to take alternative roads that are often unpaved, remote, and unsuitable for a high volume of traffic or heavy vehicles.

Accidents or emergencies occurring on these remote secondary roads are compounded by limited mobile phone and internet coverage, a lack of roadside services, and the absence of emergency rescue services. The delays associated with traveling on remote, dilapidated roads have driven up the costs of transporting commodities and other essential goods. At the same time, fuel shortages, rising petrol prices, and different tax, licensing, and customs policies enforced by competing authorities have made travel prohibitively expensive for a growing number of Yemenis.

Arbitrary searches, detention, illegal levies, and other forms of extortion at security and military checkpoints manned by an array of armed groups are common features of wartime road travel in Yemen. While the UN-brokered truce agreed in April 2022 sought to address Yemen’s road situation with a focus on the blockaded city of Taiz, it ended up being the only unimplemented element of the six-month truce.

The vast majority of the Yemenis surveyed for this policy brief said they no longer travel long distances unless it is absolutely necessary. The top reasons cited for travel in response to a general questionnaire were work obligations, family visits, seeking medical treatment at hospitals inside Yemen, and reaching airports for medical treatment abroad. The majority of respondents said security is their highest priority when planning a road trip. They reported taking a variety of precautions, such as deleting sensitive information from their phones and lying to soldiers at checkpoints about their destination, where they are from, political and regional affiliations, and profession.

Journalists, activists, or those with certain political or regional affiliations are at heightened risk for harassment, interrogation, and detention at checkpoints. Yemeni women in Houthi-controlled areas face tightening travel restrictions due to mahram (guardianship) requirements. When issued in March 2022, the mahram policy required complex and costly procedures to obtain consent from a male relative, which also had to be certified by a number of Houthi officials, before a woman could travel. Since then, the rules have become stricter; the physical presence of a mahram is now often required during a woman’s travels even if she has obtained the necessary documents to travel alone. Women who are deemed not to have met these requirements may be detained at a checkpoint until a mahram comes to pick her up. If she is a political activist, an employee of a non-governmental organization (NGO), or is affiliated with a political party opposed to the Houthis, she may be detained for multiple days, forced to pay a bribe, and sign documents pledging to follow the rule in the future. It has become increasingly clear that the mahram requirements are aimed at reducing the participation of women in civil society.

Recommendations

For international stakeholders:

- Condition the provision of humanitarian aid in Houthi-controlled areas on the group’s lifting of mahram requirements. Female aid workers are among the women targeted by the restrictions, hampering humanitarian operations. In February 2020, humanitarian aid officials and donors working on Yemen convened an emergency summit in Brussels to discuss Houthi aid obstruction. Based on that meeting, donors set up a technical monitoring group (TMG) to monitor Houthi progress toward seven conditions for aid access improvements. The TMG has succeeded in removing a Houthi-imposed 2 percent tax on aid activities and easing other restrictive regulations. The TMG should incorporate the lifting of mahram requirements into the aid access pre-conditions. The international community should also criticize the Houthis’ mahram restrictions publicly in order to spread awareness of these policies among international audiences and build public pressure against them. These efforts could also be linked to broader campaigns led by local and international NGOs to highlight predatory practices at notorious checkpoints.

- Support international and local NGOs – such as Geneva Call, CIVIC, and the National Committee for Investigating Alleged Human Rights Violations – that offer training and capacity-building programs for armed groups in Yemen designed to help them develop professional standards at checkpoints, including on issues such as when and how to conduct searches of civilians. Many of the armed forces at checkpoints are not trained on how to deal with civilians in a lawful manner on these issues and are unfamiliar with accountability mechanisms governing their behavior.

- Recognize the efforts of commercial truck driver unions and other transportation activists who organize protests and raise awareness to combat extortion and violations at checkpoints run by Houthi, Southern Transitional Council (STC), and government forces, and other armed groups. Inviting these individuals to speak at human rights events would contribute to understanding the nuances of these issues and how to address them.

- Incorporate road maintenance, repair, and development projects into cash-for-work programs funded by the World Bank, the UN, and other stakeholders in order to fill the gap left by Yemeni authorities in this area.

For the Saudi-led coalition:

- Demonstrate a commitment to Yemeni laws and the welfare of civilian motorists by discouraging proxy armed groups from instrumentalizing roads through the creation of roadblocks, extortion, arbitrary detention, and other predatory tactics. (For an example, see: ‘Route Check: Between Aden and Sana’a’).

- Prioritize road maintenance, repair, and development projects in programs funded by the Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program for Yemen and the Abu Dhabi Development Fund.

For national stakeholders:

- Streamline inspections and taxation policies at checkpoints in each governorate to ease financial burdens on the private sector and protect motorists. Although isolated efforts have been taken to address this problem, compliance is lagging. Because the cost of transportation is one of the main components of the market price of various commodities and other products, removing these types of financial barriers to the movement of goods and people can help significantly ease economic pressures on ordinary citizens.

For local authorities:

- Emulate successful efforts that have taken place on the ground to curb predatory practices at checkpoints. Such examples include:

- In October 2022, commercial truck drivers in Abyan launched a 25-day strike to protest illegal levies imposed by Security Belt forces at numerous checkpoints that amounted to about 1 million Yemeni rials (YR) per trip. The strike attracted the attention of politicians including a senior STC official and other local power brokers who were eager to resolve the issue due to the widespread economic impacts of delayed cargo deliveries. An agreement was reached to charge commercial cargo YR200,000 at one designated checkpoint in line with regulations in other governorates nominally controlled by the government.

- When criminal groups or rogue military and security forces are responsible for extorting or otherwise abusing travelers at checkpoints, coordinated security campaigns have been successful in cracking down on predatory behavior. In November, pro-government and STC-affiliated officials and security and military forces in Lahj established a joint operations room to coordinate security checkpoints in the governorate and target criminal gangs that were blocking traffic and robbing motorists.

Introduction

Road travel in wartime Yemen is rife with challenges that have made it difficult for civilians to go to work, access basic services, and obtain indispensable humanitarian aid. Likewise, wartime travel restrictions, war-damaged infrastructure, and an inability to maintain and repair roads, whether damaged by war or natural causes, have impacted commerce and aid work, making it more difficult for goods and humanitarian relief to reach their intended destinations. Drastic increases in the cost of public transportation, due to rising petrol prices exacerbated by reduced purchasing power, have further restricted mobility in general and access to markets specifically.[1] Those who brave Yemen’s roads must pass through an array of security and military checkpoints controlled by armed groups that impose illegal levies and demands. For women in particular, the Houthis have devised bureaucratic restrictions as a means of further controlling who can travel and how.

Territorial divisions among the conflicting parties have closed off several main highways within and between governorates to civilian use. Travelers must take secondary roads, which are in many cases unpaved mountain paths that were not built for a high volume of traffic or heavy vehicles.

The six-month, UN-brokered truce that ended on October 2, 2022, focused attention on Yemen’s dire road situation, in particular in Taiz governorate. However, the reopening of roads around the blockaded city of Taiz was the only unimplemented element of the truce. In mid-August, the fragility of road transportation in non-frontline areas was highlighted when fighting among anti-Houthi forces over control of Ataq, the capital of Shabwa governorate, temporarily closed the international highway to Hadramawt, where one of Yemen’s few functioning airports and the only open land port with Saudi Arabia are located.[2] This highway has since reopened but is dotted with new military and security checkpoints.

Wartime road transportation obstacles deeply impact Yemenis’ daily lives. This policy brief examines the types of threats Yemenis face on the road, the precautionary measures they take to avoid these threats, and the motives behind their travels. In many cases, the threats that constrict personal travel, whether for travelers in private vehicles or using public transportation, are also impacting commercial transport and humanitarian relief work. The places and ways in which these impacts are experienced are noted. The primary focus is on routes near the frontlines separating Houthi- and government-controlled areas, in particular roads linking Aden and Taiz, Sana’a and Marib, and Sana’a and Aden, respectively. Secondary or alternative roads that Yemenis have come to rely on are compared with the pre-war network of now inaccessible main roads.

Methodology

Interviews with 44 Yemenis (seven conducted in person in Egypt and Jordan and 37 by telephone in Yemen) were carried out between March 2021 and November 2022. Eight interviewees were drivers of buses, taxis, or commercial cargo trucks; two worked in administrative positions in private transport companies; another owned a cargo transport company. Two interviewees were Yemeni government officials, one in the Ministry of Public Works and Highways and another in the Ministry of Transport.[3] Another interviewee was a Yemeni women’s rights activist The rest were travelers. In addition to these interviews, 94 Yemenis representing 18 out of 22 governorates responded to a general questionnaire[4] distributed between August and September 2021 via WhatsApp groups frequented by Yemeni professionals in various fields; 59 percent of the respondents were men and 41 percent were women. Nearly 90 percent of the respondents were living in Yemen and reported traveling regularly by road. As a convenience sample, it should not be considered representative of Yemen’s national population. An additional questionnaire, developed exclusively for women, targeted an additional 24 women, aged 26-55, from various professional backgrounds to share their unique experiences and the difficulties that they face on the roads as women.[5] The policy brief also relied on a review of literature and news reports on road travel in Yemen during the war.

Impact of War on Yemen’s Road Infrastructure

Yemen spans about 555,000 square kilometers. More than 70 percent of its population lives in rural areas, far from basic services such as health and education facilities, and only a quarter of rural households live within 2 kilometers of paved roads.[6] Yemen’s total road network is estimated to be 58,200 kilometers long, with 40,870 kilometers, or 70 percent of it, unpaved.[7] Roads are paved in many city centers, but the vast majority of Yemen’s 17,000-kilometer-plus paved roads connect major cities and governorates. Military operations necessitate the movement of heavy vehicles and machinery, which have damaged roads nationwide that were not built to withstand such loads, exacerbating the poor condition of Yemen’s already limited road network.[8]

Roads and bridges have also been destroyed by military air strikes, landmines, and improvised explosive devices (IEDs). In June 2019, the government’s Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (MOPIC) estimated that more than 6,000 kilometers of urban and inter-governorate paved roads and more than 100 bridges had been destroyed during the conflict.[9] Subsequent estimates by Sana’a-based officials blamed Saudi-led airstrikes for damaging nearly 5,000 kilometers of paved roads and destroying or damaging 101 bridges.[10]

Roads that have not been damaged by military operations or confrontations have fallen into a state of disrepair, with road construction and maintenance projects largely suspended due to political, security, and economic constraints since the beginning of the war.[11] Heavy rain and flooding in Shabwa and Abyan governorates in 2021, for instance, damaged large parts of the road connecting Aden and Hadramawt.[12]

These problems, combined with the war’s toll on Yemen’s seaports and airports, not only have interfered with personal travel but also have caused the country’s ranking to fall in the Logistics Performance Index, a World Bank-produced measure of the quality and efficiency of trade and transport infrastructure. Yemen dropped from 63 out of 155 countries evaluated in 2012 to 140 out of 160 in 2018, the most recent year available.[13]

Adapting to Wartime Travel

Limiting Road Trips to Urgent Needs

Many sections of the main highways in the western third of Yemen, where frontlines are concentrated, have been closed, forcing travelers to take alternative, often-unpaved and dangerous routes. The road closures are mainly located near the frontlines separating the Houthi-controlled northern highlands and areas nominally controlled by the government and other anti-Houthi armed groups. In many ways, these two zones of control have come to resemble different countries, with diverging economic and political agendas that complicate both personal and commercial travel.

The vast majority of travelers queried said they no longer venture long distances in Yemen unless it is absolutely necessary. The major reasons cited by Yemenis in the general questionnaire as reasons to travel between governorates in conflict areas were work obligations (54 percent), family visits (42 percent), and seeking medical treatment at hospitals elsewhere in Yemen (21 percent). Because quality hospitals and medical centers are concentrated in the urban areas of a handful of governorates such as Sana’a, Aden, and Taiz, residents of other governorates must make arduous road journeys for treatment. Thirteen percent of respondents specified traveling to airports or other international exit points to travel abroad for medical treatment. Only 11 percent reported traveling for local tourism.[14] All of the reasons cited, except tourism, were characterized as urgent and essential.

More than 60 percent of respondents to the general questionnaire said security is their highest priority when planning a road trip. Security takes precedence over cost, comfort, driver experience and knowledge of the roads, and privacy. Nearly 80 percent of these respondents said they prefer to travel during the day because they feel a greater sense of security during daylight hours. Fifteen percent perceived the night as a safer time to travel. One individual in the latter category reasoned that overnight checkpoint personnel are less vigilant, meaning shorter wait times and less chance of being interrogated or detained.[15]

Passing through checkpoints can be expensive, as demands for bribes are commonplace, and doing so carries personal risks, which vary depending on one’s profession, sex, and political, religious, and regional affiliations. Nearly 40 percent of respondents to the general questionnaire said that they, one of their relatives, or people in the same vehicle with them were prevented from traveling past checkpoints for such reasons.

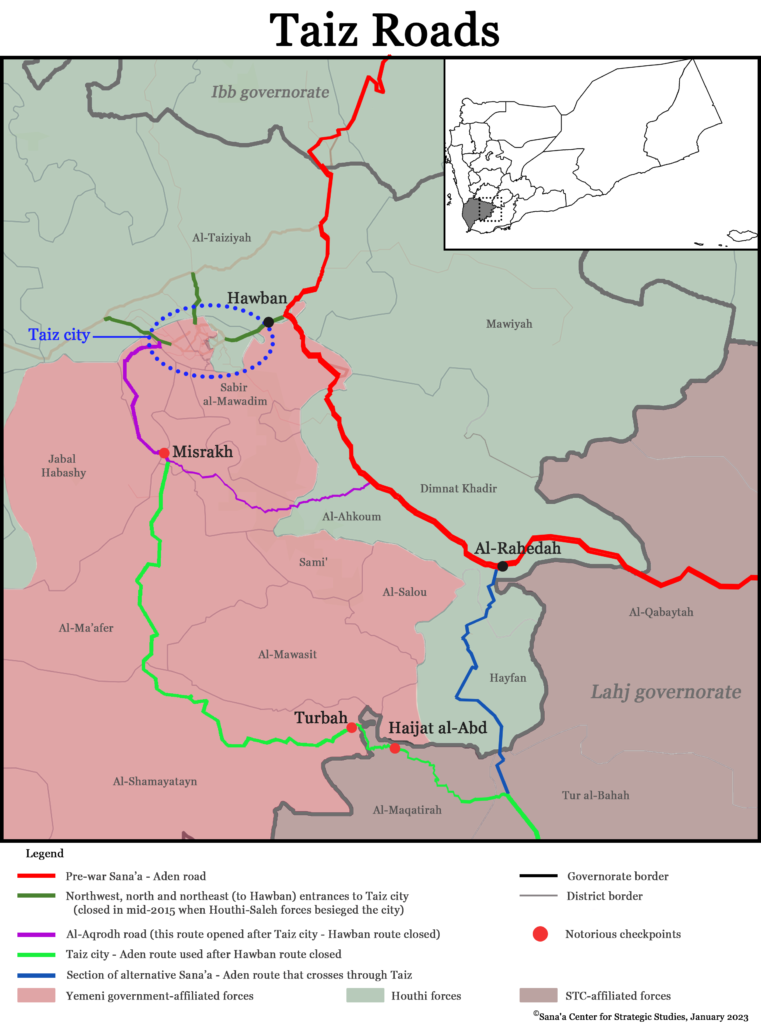

In many cases, traveling even entirely within a governorate has become exceptionally difficult and time-consuming. Taiz is a clear example. Houthi forces have effectively besieged its capital of the same name since mid-2015, blocking access to all three of the main roads into and out of the city on its northwest, northern and eastern outskirts. The rugged Talooq mountain range south of the city is dangerous by car. A trip that once took less than 15 minutes on a paved road from the government-controlled city center to the Houthi-controlled Hawban industrial area now takes five to six hours on a narrow mountain road through the Al-Aqrodh area that necessitates a circuitous 60-kilometer detour through the lower valleys of the Talooq mountains.

Following several failed attempts to secure Houthi buy-in for the reopening of roads in Taiz, the UN special envoy, Hans Grundberg, proposed a compromise in July that would reopen four roads in stages: two in Al-Dhalea, one in Sa’ada, and the Sofitel road in Taiz (which leads to the Hawban area).[16] That proposal failed to gain traction with Houthi negotiators before the truce ended.

The road from the southern border of Taiz to Taiz city has an estimated 38 official military and security checkpoints manned by forces affiliated with the pro-Islah Taiz Military Axis. Rogue military and security forces and criminal gangs have also established makeshift checkpoints to extract “fees” or simply to rob motorists.

Security Checkpoints: Satellite Offices of the War Economy

Amid the collapse of the state and reorganization of existing centers of power during the war, an array of armed groups with conflicting ideologies and agendas have emerged. All major armed groups operate roadside checkpoints in areas they control as a means to monitor who is coming and going and/or to monetize the flow of traffic in various ways. These checkpoints often lack standardized procedures and professional standards for the security and military personnel manning them, which leaves travelers vulnerable to arbitrary inspection, interrogation, and detention.

Extortion is a common practice at checkpoints, whereby motorists are forced to pay a fee (bribe) or provide something else of value to facilitate their passage. These sums are paid either by the passengers or by the driver of the vehicle if it is a taxi. A number of newer taxi companies that have emerged during the war, such as Sana’a-based Arhab for Rental Cars, charge exorbitant fares in part because they have developed financial relationships with the security checkpoints and their commanders.[17] In exchange for information about the taxi passengers and a fee, the authorities at the checkpoints allow them to pass through more quickly, unless passengers are flagged for reasons such as political activism, belonging to an opposition political party, or, in the case of women, not meeting Houthi mahram (guardianship) requirements (see below: ‘ Mandatory Guardians: An Additional Burden for Women’). Commercial cargo trucks are the most lucrative targets for extortion; drivers are forced to choose between paying bribes or potentially costly shipping delays. The journeys of people traveling by bus tend to take the longest because each passenger’s luggage and identification is checked by forces at key checkpoints.[18]

Threat of Arrest, Extortion for Journalists and Activists Who Travel

Another common practice at checkpoints is the search of mobile phones, tablets, and laptops, which adds to traveler wait times. Often, the search of electronic devices results in the discovery of content that can be leveraged for extortion. One respondent told the Sana’a Center that he noticed during his travels from Sana’a to Taiz that soldiers at Houthi checkpoints often ask travelers about their profession, their employer, and where their offices are located. The phones of journalists are thoroughly searched, he said, for content that will support “any accusation, whether a photo or participation in communication sites (like Facebook or WhatsApp).” In an attempt to avoid these encounters, the traveler, who is a reporter, changed the profession listed on his passport from “journalist” to “employee.”

Another traveler said that Houthi forces confiscated his electronic devices at a checkpoint in the Hawban area of Taiz on allegations that his work for a civil society organization helped opposition forces identify Houthi military sites. The traveler said he was released after being searched and interrogated, but his devices were not returned. Several respondents reported mistreatment at checkpoints, including being detained after searches of their phones revealed their participation in political and human rights activism on social media. One traveler told the Sana’a Center that after his devices were seized at an STC checkpoint in Aden, anonymous individuals contacted him threatening to publicize compromising content found on the devices if he did not send them money.[19]

Fifty-nine percent of respondents reported that their biggest fears during road travel were detention or interrogation, compared to 42 percent who cited the outbreak of clashes between combatants and 40 percent who expressed concern about accidents due to poor road conditions. Many of these fears are well-founded. Nearly 60 percent of the respondents said they had experienced thorough inspections at checkpoints, while about 30 percent reported having their electronic devices searched. About 45 percent of respondents said they had been caught in torrential rainstorms and about a quarter of them had been involved in road accidents. Nearly a third of the respondents said they had experienced shooting and clashes during road travel.

Role of Regional Discrimination in Mistreatment of Travelers

Outside of Houthi-controlled areas in some southern governorates, regional discrimination against northerners has become the norm and is used as justification to mistreat travelers at checkpoints. Discrimination against Yemenis from northern governorates started in the early months of the war in mid-2015 after forces loyal to the Houthis and their then-ally former President Ali Abdullah Saleh were driven out of the interim capital, Aden, by forces including southerners trained and equipped by the UAE. In particular, the Emirati-backed Security Belt forces were formed to protect Aden’s surroundings from any new attacks. These paramilitary forces subsequently came under the command of the UAE-backed STC, which was formed in May 2017 and became the dominant political group in Aden after expelling the internationally recognized government from the city in August 2019. The STC and its allied forces went on to consolidate power in key cities in surrounding governorates, including Ataq in August 2022.

Security Belt forces manning what is known as the Iron Factory (Masn’a al-Hadeed) checkpoint outside Aden are notorious for turning away northerners trying to enter the interim capital.[20] Respondents to the general questionnaire from the northern governorate of Taiz also spoke of mistreatment at the Ribat and Al-Alam checkpoints outside Aden, which are manned by Security Belt forces, because of their regional identity.

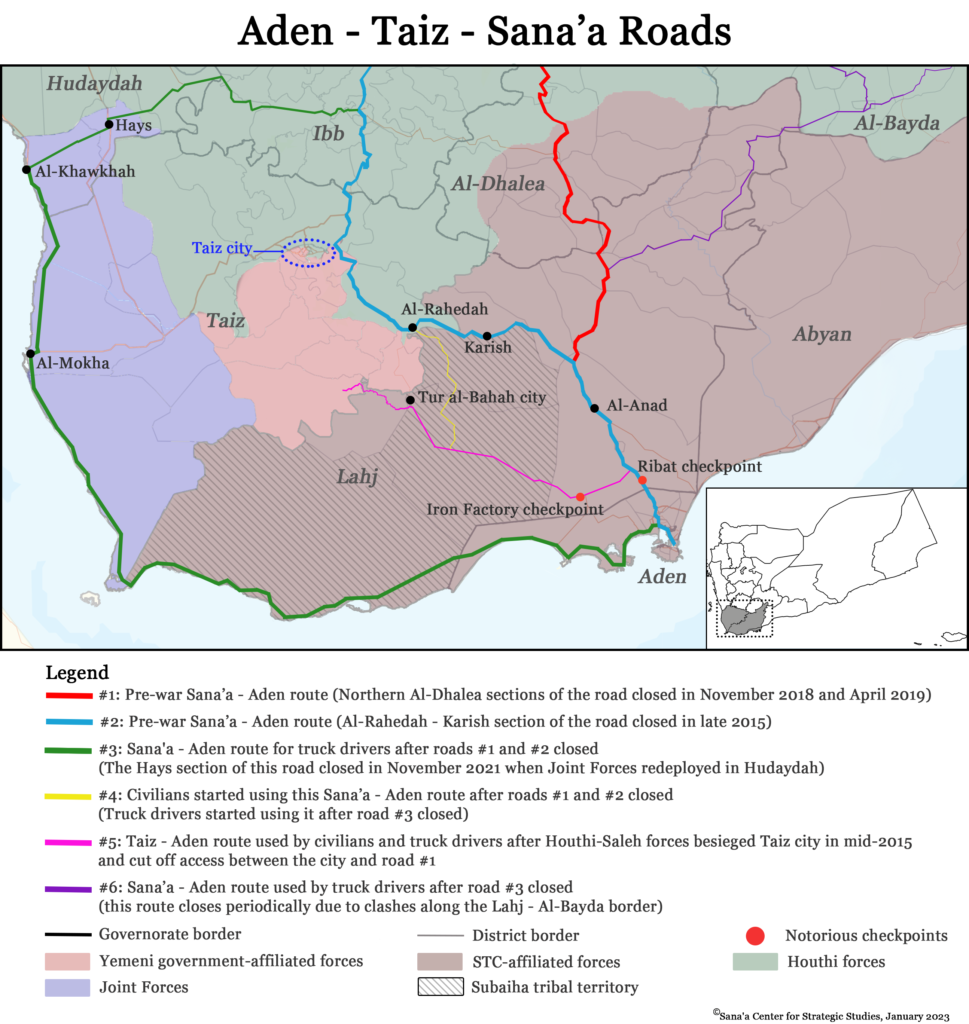

Before the war, the main route from Aden to Taiz ran northward through the Al-Anad area of Lahj governorate’s Al-Tuban district. In August 2015, a large section of the route (between Karish and Al-Rahedah) was closed after fighting broke out along the Karish front in northern Lahj’s Al-Qabaytah district and Saudi-led coalition airstrikes destroyed several bridges there. Since then, the area has been heavily mined by Houthi forces and motorists have been forced to take alternative dirt roads to the west through open desert and rugged mountains. From Aden, the alternative route heads northwest through Tur al-Bahah district. Motorists heading to Taiz city will continue driving northwest and pass through Al-Maqatirah district in northern Lahj before reaching Al-Turbah city in southern Taiz. Those traveling to Houthi-controlled parts of Taiz or other Houthi-held governorates such as Ibb, Dhamar, or Sana’a will follow a dirt road northward in Tur al-Bahah over a dangerous mountain pass in Lahj’s Al-Qabaytah district to the city of Al-Rahedah in southern Taiz. Traffic accidents have increased on this route since truck drivers began using it to travel to and from Houthi-controlled areas after the November 2021 redeployment of Saudi coalition-backed Joint Forces[21] on the Red Sea Coast led to the closure of a main highway in southern Hudaydah’s Hays district.

The routes from Aden to southern Taiz via Lahj have a number of military and security checkpoints manned by forces affiliated with the Houthis, Islah, Giants Brigades, and the STC. In addition to these official checkpoints, makeshift checkpoints set up by rogue military and security forces as well as criminal gangs and armed tribesmen extract additional levies from or rob motorists.

… And Taiz to Aden

Traveling in the opposite direction, from Taiz to Aden, poses a different set of risks for some travelers. STC-affiliated security forces manning the Ribat, Al-Alam, and Iron Factory checkpoints on the outskirts of the interim capital routinely single out northerners for extortion, detention, or other forms of mistreatment.[22] These practices decreased to an extent immediately following the April 2022 formation of the Presidential Leadership Council,[23] whose creation sought to ameliorate divisions among anti-Houthi groups but have since reemerged.

The trip from Taiz city to Aden used to take about 2.5 hours, but extensive damage to bridges and other parts of the Karish-Al-Rahedah section of the road led to its closure in August 2015.[24] Now it takes at least eight hours to drive from one city to the other using an alternative route that is mostly unpaved. One of the most dangerous sections of the route is through Haijat al-Abd, a steep series of switchbacks where trucks frequently get stuck and flip over. Another unpaved stretch of the road, called Al-Saylah Al-Maqatirah, is only wide enough for one vehicle at a time.[25]

Mandatory Guardians: An Additional Burden for Women

Traveling during the war in Yemen is difficult for all segments of society, but women face unique and growing challenges. In addition to the general risks, inconveniences, and uncertainties facing motorists nationwide, Yemeni women in Houthi-controlled territory are subjected to travel restrictions within and between governorates.

While many Yemeni families long have required men to accompany female relatives who are traveling, the Houthis began a process of formally imposing such a guardianship requirement on all women and girls as they solidified their authority in and around Sana’a. Liza Badawi, coordinator for the Yemen-based Women’s Solidarity Network,[28] noted other ideological and practical considerations that inform the mahram policy. In ideological terms, the Houthis hold a patriarchal worldview in which women in general, even Hashemite women who are part of the ruling class in the Houthi system, have fewer rights than men. Practically, by restricting the participation of women in civil society, the Houthis are able to monitor the movements of women engaged in activities that may be perceived as a threat to the group.[29]

Mahram requirements noticeably tightened in the days after the December 2017 Houthi killing of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, when women political activists took to the streets to demand the return of Saleh’s body. Badawi said that the incident raised the alarm for Houthi authorities that women have an influential voice in society and pose a potential threat to the group’s rule. An early move to enshrine the practice in law occurred in Houthi-controlled Hajjah city in September 2021, when local authorities issued a circular stating that it is “not allowed for a woman to use transportation means without a mahram.” The fine for violating the law was set at 200,000 rials, then about US$330, and a cow.[30]

Women who traveled without a mahram have faced frequent harassment at checkpoints in Houthi-run areas. In March 2022, Houthi authorities imposed further mahram requirements have been more strictly enforced.[31] The circular states that before any woman travels alone, she must obtain written consent from a mahram, which must then be certified by the aqil, a male neighborhood representative, and other government officials. Sometimes, these consent forms are not accepted and the physical presence of the mahram is required during a woman’s travels.[32] She must also be able to prove the relationship to her mahram at Houthi checkpoints. If soldiers manning the checkpoints conclude that a woman traveling without a mahram does not have the required approvals, she may be detained until a mahram comes to pick her up. If she is a political activist, an employee of a local or international NGO, or is affiliated with a party that opposes the Houthi authority, she may be detained for multiple days. When a mahram is permitted to escort her home, they may have to pay a bribe and sign a pledge that it will not happen again.

In practice, the requirements for obtaining such approvals and the punishments imposed on women who do not follow these rules vary. One woman relayed her experience with the mahram process to the Sana’a Center:

“A legal secretary in a woman’s neighborhood drafts the document, takes the signature, fingerprints, and identity card of the mahram, and then stamps it. The woman then writes a statement agreeing to the mahram requirements, which must be signed by two witnesses. The document is then signed by the legal secretary and then a court official. After that, the Ministry of Justice must approve the document and, if the woman is traveling outside the country, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs must approve it.”[33]

The neighborhood aqil, who liaises with Houthi authorities, was included in the approval process because he is intimately aware of the residents in his area and knows their connections. Transportation companies have also been integrated into the approval process. Women are required to fill out mahram forms with car rental agencies or taxi services,[34] which are shared with the security and military checkpoints along her travel route. This information allows Houthi authorities to conduct background checks on women before they arrive at checkpoints. In this way, female activists and employees of NGOs, whose work requires frequent travel, have been the main targets of the policy. Restricting women’s movement has imposed other economic hardships as well.

One woman told the Sana’a Center that the costs of obtaining all of the necessary signatures during the approval process amount to YR15,000.[35] This represents a significant economic burden on women, whether they are traveling for work, to receive medical treatment, or simply to visit relatives. Another woman employed by an international NGO said she was refused permission at a checkpoint to travel with documents alone, necessitating her husband to travel from Aden to Sana’a, where she was at the time, to accompany her to Aden’s airport. His round trip totaled 32 hours of road travel solely to allow his wife to reach the airport.[36]

By normalizing the Houthis’ mahram requirement, women elsewhere are further exposed to potentially violent incitement if they travel alone. While most of the respondents said that they were asked about a mahram in northern (Houthi-controlled) areas, some also experienced harassment at checkpoints manned by Salafi and other conservative religious forces in southern governorates. Several of the respondents to the women-only questionnaire who had traveled without a mahram said they suffered insults at security checkpoints from soldiers affiliated with various armed factions. Fifty-four percent of respondents said they experienced some kind of harassment while traveling due to their sex, and seven out of 12 who elaborated on this harassment cited their travel without a mahram as a reason for this. The lack of policewomen at most security checkpoints makes matters worse. Women reported feeling violated when male police officers searched their purses and suitcases.

One Yemeni woman who works for an NGO described the mahram policy as part of a plan to gradually isolate women and “take us back to the time of the Imamate.”

“The Houthi authorities are afraid that the women (like me) will influence their women, or even their men,” she said. “We will soon disappear from the social arena.”[37]

To deal with these issues, women reported taking a number of precautions, including wearing the niqab, a veil that leaves only the eyes exposed, as well as traveling only with a mahram, traveling within a group, removing sensitive content from mobile phones, deleting WhatsApp or other messaging apps, and contacting relatives and others who have traveled a particular route to ask about the type of difficulties they might face.

Discomfort to Danger: Service Deficiencies on Alternate Routes

Accidents, Breakdowns, and Emergency Services

There are very few hospitals and clinics outside of major cities, making emergencies like traffic accidents far more dangerous than they would be otherwise. Road accidents in Yemen frequently go unreported, but pre-war figures from 2013 put the number of accidents nationwide at nearly 9,000, resulting in 2,494 deaths and 12,622 injuries.[38] During 2018 and 2019, when individuals were less likely to file accident reports and authorities’ capacity to document them was diminished, recorded accidents reached 11,405, resulting in 2,653 deaths and 16,403 injuries.[39] The closure of paved highways designed for high traffic volumes and heavy vehicles has forced cargo trucks, passenger buses, and other motorists to use secondary roads that are often unpaved, unmaintained, and not engineered to handle these loads, which has contributed to traffic accidents.[40] When accidents or emergencies do occur, it can be particularly difficult to summon help when a lack of mobile and internet phone coverage is combined with remote, rough roads and virtually no emergency rescue services. One respondent to the questionnaire for women told the Sana’a Center that her pregnant niece had a miscarriage while traveling from Sana’a to Aden, believed to be related to poor road conditions. Even before the war, there were few ambulances available to help motorists involved in serious traffic accidents or other health emergencies on the road, but access to paved, more direct roads made travel safer.

There are few car repair shops outside major cities, so when vehicles break down, travelers may wait hours for help to arrive. The respondent to the questionnaire for women whose niece had a miscarriage said that when the bus she was traveling on got stuck on the Al-Saylah Al-Maqatirah dirt road in southern Taiz, there was no way to contact anyone for help. The 10-kilometer stretch of road, which is potholed, rocky, and wide enough for only one vehicle to pass at a time, becomes a river during rainstorms. A respondent to the general questionnaire who was with his wife and children on the Ibb-Sana’a road reported waiting three hours late at night for help after a small problem with his car. Catching a ride to pick up what he needed to fix the car would have required leaving his family alone on the remote road, so he waited for a friend to arrive from farther away with the part. Tow trucks, if affordable, are frequently unavailable outside cities.

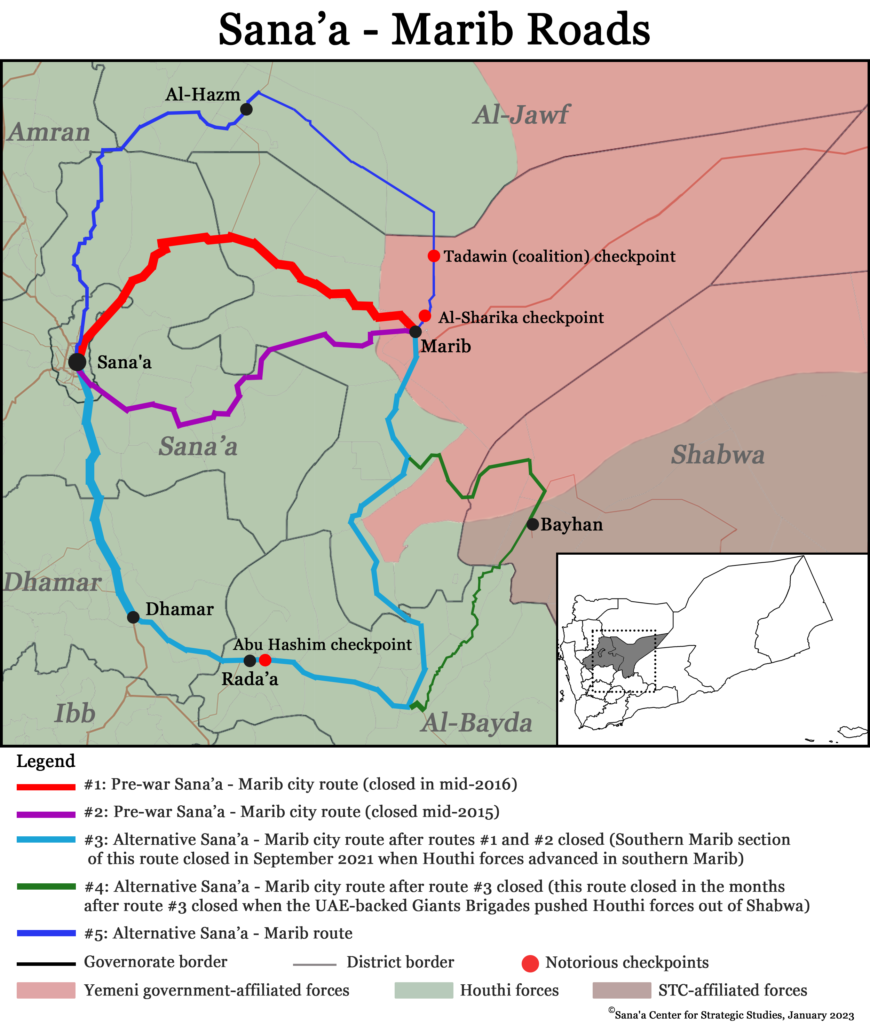

Before the war, there were two main roads between Sana’a and Marib city that were paved and lined with petrol stations, markets, and restaurants, and took less than three hours to travel. When sections of them were closed in mid-2015 and mid-2016, as frontline fighting intensified in western and northwestern Marib, travelers were forced to take long detours either northward through Al-Jawf governorate or southward through Dhamar and Al-Bayda governorates. The southern route, which then ran through Marib’s Mahliya, Rahabah, and Al-Jubah districts, was open until early September 2021 when Houthi forces advanced into southern Marib and toward neighboring Shabwa governorate. Full of potholes and speed bumps, and lacking gas stations, car repair shops, and mobile network coverage, this route took upwards of 14 hours to travel.

During battles that followed, in which UAE-backed Giants Brigades expelled Houthi forces from northwestern Shabwa and parts of southern Marib, the Houthis closed the Al-Manaqil section of this route between northeastern Al-Bayda and southern Marib. Al-Manaqil was considered one of the most important main roads for residents and merchants traveling from Houthi-controlled governorates to eastern Hadramawt governorate, where Yemen’s only functioning border crossing with Saudi Arabia (Al-Wadea) and one of the country’s few functioning airports (in Seyoun) are located. Travelers now incur higher costs and longer travel times along one of two alternative routes. The first, open since September 2021, heads northeast to Shabwa’s Bayhan district then northward through remote desert to the Safer oil facilities east of Marib city. This route takes about 20 hours to travel and is closed during intermittent clashes on the Bayhan front. The second route passes through remote desert in Al-Jawf and northern Marib and lacks any services.

Checkpoints between Sana’a and Marib are manned by forces affiliated with the Houthis as well as pro-government and tribal forces.

Traveling Longer with Limited Rest Areas, Public Facilities on Secondary Routes

All travelers in Yemen face a significant shortage of other basic services, such as clean or merely functioning public toilets, open petrol stations, grocery stores, and restaurants, though availability and quality vary by route. Many of the older petrol stations have closed because of recurrent fuel shortages and the increase in black market fuel sales. Still, 89 percent of respondents to the general questionnaire, men and women, described the cleanliness of public restrooms as poor. Thirty-five percent described the availability and distribution of basic services and facilities on the road as poor, 57 percent said that they were acceptable, and less than 8 percent of the sample said they were good. In terms of how well the available basic services and facilities fulfilled their needs, 34 percent of all respondents described their quality as low, 58 percent as acceptable and average, and 3 percent as good.

However, female travelers, who require bathrooms, rest areas, and restaurants with private spaces for families and women, were inordinately impacted. Of the 24 women who completed the questionnaire specifically designed for women, 90 percent of the respondents described the available services and facilities as poor. Two-thirds of the respondents stated that they did not feel safe using these facilities and services. Ninety-one percent of them said that women’s travel between governorates has become more difficult due to the war.

The High Cost of War on the Road Transport Sector

Yemen’s road transport sector has been particularly hard hit by the war’s division of the state into opposing central authorities in Sana’a and Aden that compete over key public institutions. For state employees, the nonpayment of salaries and meager budgets to fund road maintenance and development projects have contributed to an exodus of workers. Private companies, meanwhile, must contend with high diesel and petrol prices exacerbated by recurrent fuel shortages and adhere to different tax, licensing, and customs policies enforced by the dueling central authorities and local authorities — in addition to paying bribes or arbitrary fees at checkpoints manned by armed groups.[41]

Delays stemming from long detours on secondary roads between Aden, Sana’a, Hudaydah, Marib, Al-Bayda, and Dhamar represent another factor driving up transportation costs. Some trips from the country’s main seaports to Sana’a that took a day or two before the war now take more than five days. For example, before the war in 2013, it cost about YR350,000 for a merchant to hire a truck and a driver to transport a 40-foot container of goods from Aden to Sana’a. That price included the cost of fuel and all of the fees charged at official customs points and weigh stations. Today, the merchant will pay about YR3-4 million for the same journey because fuel costs are higher, the available routes between Aden and Sana’a are longer, and the drivers are forced to pay a number of additional official and unofficial fees at checkpoints manned by an array of armed groups along the way.[42]

The closure of many air, sea, and land ports has further burdened the road transport sector. Of Yemen’s 19 airports,[43] only two of them (in the interim capital Aden and in Seyoun, Hadramawt) are fully operational for civilian flights. As part of the UN-brokered truce launched in April 2022, Sana’a airport was reopened for a limited number of weekly flights to and from Amman and Cairo although the latter route was not sustained after two initial flights on June 1.[44] Despite the truce lapsing in early October, Sana’a airport has remained open to civilians, albeit in a limited capacity and with similar travel restrictions that motorists face.

Most of the country’s 17 seaports are also completely or partially closed. The main ports that remain open are the port of Aden, the port of Mukalla in Hadramawt, Nishtun port in Al-Mahra, and the ports of Hudaydah, the latter of which are subject to UN inspections as part of a UN Security Council arms embargo established in April 2015.[45] These travel restrictions have hindered commercial transportation operations and contributed to price hikes of fuel and food commodities.

Of Yemen’s six international land ports,[46] only Al-Wadea border crossing with Saudi Arabia and Shahin and Sarfit border crossings with Oman are currently open.

Conclusion

The challenges and risks related to road transportation during the war – in particular near the frontlines in the western third of the country – are taking a serious toll on Yemeni lives. Yemenis face an array of dangers on the limited network of roads that remain open including combat operations and landmines and IEDs. Accidents on the remote and often unpaved alternative roads that detour road closures are particularly prone to flooding and landslides and can be fatal for ill or injured people seeking urgent medical attention. Competing armed groups have established hundreds of roadside checkpoints to monitor and monetize the flow of traffic. Journalists, activists, members of opposition political parties, and travelers from certain regions are often singled out at checkpoints and are at greater risk of illegal searches, interrogation, and detention.

Women face unique and tightening travel restrictions. The Houthi-imposed mahram (guardianship) policy subjects female travelers to costly and complex bureaucratic procedures to obtain permission to pass through Houthi-manned security checkpoints without a male escort. In late October, women reported that despite obtaining all of the necessary authorizations to travel alone, Houthi authorities required them to travel with a mahram by their side.

Economic and humanitarian conditions are closely tied to the road situation, so improvements in the latter can significantly reduce suffering in the former. However, easing road restrictions can also have major military and political repercussions, which creates pushback from the warring parties. Because of its central importance to so many stakeholders, lifting road restrictions is a potentially valuable lever in negotiations that needs to be further explored.

Many of the complexities, challenges, and risks related to wartime road travel outlined in this policy brief have received inadequate attention from local and external stakeholders in Yemen. This can be inferred from the scarcity of research on the subject. Much of the available literature is outdated and tends to be superficial in its scope and content. Although the recently expired truce contained efforts to alleviate the suffering associated with road closures in several governorates, it was the first attempt by international actors to prioritize the issue in more than eight years of war. And it was also the only element of the truce that was not implemented. Focusing attention and resources on the issues surrounding wartime road travel and how to dismantle and resolve its complexities would represent a positive step that could alleviate long-lasting, intertwined, and accumulating suffering.

This policy brief was produced as part of the Yemen International Forum 2022, organized by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies in cooperation with the Folke Bernadotte Academy, and with funding support from the Government of the Kingdom of Sweden.

- “Inter-agency joint cash study: market functionality and community perception of cash based assistance,” REACH, December 2017, p. 35, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/reach_yem_report_joint_cash_study_dec2017.pdf

- In mid-August 2022, amid clashes between Islah-affiliated military forces and UAE-backed Shabwani Defense Forces and Giants Brigades over control of Ataq, the government’s Ministry of Transportation sent a memo to mass transport companies to suspend trips indefinitely along the Shabwa-Hadramawt road. The closure was precipitated by a suspected UAE drone strike on a passenger bus. See “Shabwa..a mass transport bus driver killed and his escort injured in Emirati plane bombardment,” Al-Mahra Post, August 16, 2022, https://almahrahpost.com/news/32801#.Y1rsJezMIbk

- Yemen’s road network and transport infrastructure sectors have traditionally been managed by these two ministries. “Internal and External Obstacles to the Transfer of Goods in Yemen: Causes and Consequences,” Yemen Economic Forum of the Studies and Economic Media Center, 2022, pg. 6, unpublished paper.

- Ten of the 94 respondents did not identify their home governorates. The four governorates not represented were Sa’ada, Raymah, Al-Jawf, and Amran.

- The respondents were from eight governorates: Aminat Al-Asimah, Sana’a, Ibb, Aden, Abyan, Hadramawt, Shabwa and Al-Bayda.

- “Yemen Transport Sector: Input to the Yemen Policy Note no. 4. on Inclusive Services Delivery,” World Bank Group, April 2017, p. 3, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/pt/636961508411397037/pdf/120532-WP-P159636-PUBLIC-Yemen-Transport-Input-Note-4-10-17WE.pdf

- Nabil Al-Tairi, “The road transport sector in Yemen: Critical Issues and Priority Policies,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies/DeepRoot Consulting/CARPO, Rethinking Yemen’s Economy White Paper, March 2022, pp. 9-11, https://devchampions.org/uploads/publications/files/Rethinking_Yemens_Economy_No11_En-1.pdf

- Law No. 23 of 1994 regulates the maximum weight and overall dimensions of goods-transporting vehicles in Yemen. However, the regulations have largely been ignored during the war, in part due to a shortage of functioning weigh stations throughout the country and because many of the roads that can handle heavy loads are closed. Ibid, pp. 8-9.

- “Reconstruction and Economic Recovery Priorities Plan: Urgent Priorities (AR),” Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, June 2019, p. 54, http://www.yemenembassy.ca/doc/ARABIC Yemen DNA Phase 3-final (Informal Arabic Translation)-2.pdf

- Telephone interview with an engineer from the Roads Maintenance Fund in Sana’a, June 4, 2021. For Ministry of Public Works and Highways, see, “$3.3 billion dollars of damages to roads inflicted by the aggression in six years,” 26 September Net, March 28, 2021, https://www.26sep.net/index.php/local/12557-3-3-6

- Interview with an official from the Ministry of Public Works and Highways, Aden, January 4, 2022.

- Telephone interview with a traveler, October 27, 2021.

- “Country Score Card: Yemen, Rep. 2012,” World Bank website, https://lpi.worldbank.org/international/scorecard/column/254/C/YEM/2012#chartarea; “Country Score Card: Yemen, Rep. 2018,” World Bank website, https://lpi.worldbank.org/international/scorecard/column/254/C/YEM/2018#chartarea

- Interviewees and survey respondents indicated a preference for tourist destinations within the areas of control of each conflict party in which they lived. For example, most of the people living in Houthi-controlled areas who shared their travel preferences said they travel to Hudaydah, Ibb, Raymah and Al-Mahwit governorates.

- Interview with a Yemeni traveler, August 18, 2022.

- “Yemen: Houthis Should Urgently Open Taizz Roads,” Human Rights Watch, August 29, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/08/29/yemen-houthis-should-urgently-open-taizz-roads

- Interview with a Yemeni traveler, August 18, 2022. For an image of the form that now must be filled out by women travelers renting a car from Arhab, see: “The first comment on the decision to move women with a Mahram between provinces,” Crater Sky, April 18, 2022, https://cratersky.net/posts/101592

- Aisha Al-Warraq, “Yemen’s Travel Saga: Unexpected Airport Traffic and Perilous Roads,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 10, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/8186

- Interview with a Yemeni traveler, May 25, 2021.

- “Scenes from citizens’ trips to Aden… Kinds of dishonor and humiliation (report),” Al-Mawqea Post, January 5, 2018, https://almawqeapost.net/reports/26543

- The Joint Forces consist of the National Resistance forces, the Giants Brigades, and the Tihama Resistance forces.

- These forces argue that the extra security measures are necessary precautions to prevent Houthi militants from establishing sleeper cells in Aden, but the actions are also part of a wider trend of discrimination against northerners in general by hardline secessionists.

- Interview with a Yemeni traveler, August 18, 2022.

- Abdulrab al-Fattahi, “‘Karish Line’ Seven years of stopping life,” Hayrout, April 29, 2022, https://hayrout.com/117119/

- During heavy rains, Al-Saylah Al-Maqatirah becomes an impassable flood zone. See Osama al-Qutibi, “Catastrophic torrential rains in Taiz, closing the city’s only outlet,” Belqees TV, August 29, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4lKvjv9mzXE

- Whenever these forces had problems with then President Hadi, they closed the roads leading through Al-Dhalea and Radfan districts, in particular, and increased harassment of northerners traveling to southern governorates. These incidents were framed as southerners demanding statehood, but in reality were driven by government-STC tensions.

- Aisha Al-Warraq, “Yemen’s Travel Saga: Unexpected Airport Traffic and Perilous Roads (AR),” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 10, 2019. https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/8186

- The Women’s Solidarity Network, a group that advocates for women’s rights and lobbies the international community to take a stance against violations facing Yemeni women, is engaged in advocacy related to the Houthis’ mahram policy.

- Interview with women’s rights activist Liza Badawi, August 13, 2022.

- “Ansar Allah (Houthi) Group Practices Gravely Undermine Women’s Rights,” Mwatana for Human Rights, March 8, 2022, https://mwatana.org/en/undermine-women/

- Reports of harassment at checkpoints and more strict enforcement of mahram requirements were echoed several times in the women’s questionnaire. See also “Ansar Allah (Houthi) Group Practices Gravely Undermine Women’s Rights,” Mwatana for Human Rights, March 8, 2022, https://mwatana.org/en/undermine-women/

- Interviews with two women seeking mahram approvals, October 11, 2022.

- Interview with a woman seeking mahram approval, October 11, 2022.

- For an image of a private company’s form that now must be filled out by women travelers renting a car, see: “The first comment on the decision to move women with a Mahram between provinces,” Crater Sky, April 18, 2022, https://cratersky.net/posts/101592

- Interview with a woman seeking mahram approval, October 11, 2022.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Central Statistics Organization, “Statistical Yearbook 2013, Chapter 12: Transport and Travel, Table 6: Vehicle Accidents Recorded by Type of Accident, Injuries and Deaths and Human Damage in the Governorates of the Republic: 2011-2013.” http://www.cso-yemen.com/publiction/yearbook2013/Transport_Travel.xls

- Central Statistics Organization, “Statistical Yearbook 2019, Chapter 12: Transportation and Travel, Table 6: Reported Vehicle Traffic Accidents in the Governorates by Accident Type, Number, Human Casualties and Deaths: 2011-2013.” (unpublished data).

- See, for example: “8 dead in Al-Baydha traffic accident,” Almasdar Online English, November 6, 2019, https://al-masdaronline.net/local/59

- Wafeeq Saleh, “A multi-armed economy: How Houthis reap massive public revenues without providing services,” Almasdar Online English, March 9, 2022, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/921; Nabil Al-Tairi, “The road transport sector in Yemen: Critical Issues and Priority Policies,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies/DeepRoot Consulting/CARPO, Rethinking Yemen’s Economy White Paper, March 2022, p. 20, https://devchampions.org/uploads/publications/files/Rethinking_Yemens_Economy_No11_En-1.pdf

- “Internal and External Obstacles to the Transfer of Goods in Yemen: Causes and Consequences,” Yemen Economic Forum of the Studies and Economic Media Center, 2022, pg. 13, unpublished paper.

- A list of airports in Yemen, 3rabica Website (the Free Arabic Encyclopedia), https://3rabica.org/قائمة_مطارات_اليمن

- “1st Cairo-bound flight leaves Sana’a,” Saba News Agency, June 1, 2022, https://www.saba.ye/en/news3189139.htm; “145 passengers arrive at Sana’a Airport from Cairo,” Saba News Agency, June 1, 2022, https://www.saba.ye/en/news3189229.htm

- “About UNVIM,” United Nations Verification and Inspections Mechanism for Yemen, Accessed August 25, 2022, https://www.vimye.org/about

- Along the Saudi border there are four land ports: Al-Wadea in Hadramawt governorate, Haradh in Hajjah governorate, and Boqaa and Olab in Sa’ada governorate; Along the Omani border there are two land ports: Shahin and Sarfit in Al-Mahra governorate.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية