Executive Summary

Yemen faces grave ecological risks and agricultural challenges that imperil its long-term stability if left inadequately addressed. The multi-disciplinary analytical framework of political ecology – which examines the intersection of environmental, economic, and socio-political factors, and how power dynamics impact control and access to resources – can be employed to better inform context-specific solutions in recovery assistance. An understanding of Yemen’s development history, agricultural modernization, and localized political ecologies is essential for aid and development interventions to be more effective, relevant, and equitable, and to avoid harm.

Through a desk review of literature, key informant interviews, an expert discussion, and a survey on local perceptions of agriculture projects in 14 governorates, this study sheds light on Yemen’s pressing challenges and opportunities to support local communities facing environmental- and climate-related crises. It found that while international aid systems have attempted to better incorporate environmental issues and the global impact of climate change into strategies, frameworks, and tools, these top-down efforts are often not meaningfully localized. Some key agencies now require and support implementing partners to mitigate environmental and social risks – a positive step that, with increased time and resources, could lead to more robust, informed, and successful interventions. Nonetheless, local perceptions of aid and development projects reveal shortcomings in needs assessments, the incorporation of stakeholder voices and local knowledge, assessments of potential tensions, and overall project success. These are gaps that relevant aid actors must address.

Recommendations in Brief

For donors and policymakers

- Require and adequately fund comprehensive socio-environmental studies and risk assessments and allow time for iterative and adaptive projects based on community input.

- Facilitate and fund coordination and complementarity between analytical agencies to enhance operational organizations.

- Pressure national authorities to allow access for more data collection activities.

For aid agencies and practitioners

- Study Yemen’s localized political ecologies, with a commitment to local knowledge and perceptions, and equitable partnership and leadership.

- Facilitate cross-learning with local civil society and encourage culturally sensitive education on socio-environmental safeguarding.

For conflict negotiators and observers

- Incorporate socio-environmental concerns into peacebuilding efforts, and advocate for environmental justice and investment in agricultural production and socio-environmental solutions.

- Avoid framings of future ‘climate conflicts’ as inevitable.

For international and local agriculture experts and actors

- Promote an ecologically sensitive, socio-economically attuned agricultural sector.

- Continuously evaluate the socio-environmental consequences of increased investments in local food production and avoid socio-economic stratification, conflict, and ecological degradation.

- Implement locally driven social change campaigns on environmental safeguarding in agricultural production.

- Study the history of legal and community-based regulations for water and land resource management.

- Weigh the positive and potential negative effects of incorporating new technology, avoiding negative externalities similar to those that developed from the mechanization of Yemen’s agricultural system.

Introduction

Peace, development, and humanitarian practitioners in Yemen are increasingly cognizant of climate change’s acute impact on displacement[1] and conflict.[2]Described as a “threat multiplier,”[3]climate and conflict researchers have underscored the magnitude of environmental challenges facing current aid efforts and future recovery endeavors in Yemen,[4] with runaway ecological breakdown identified as the country’s “biggest risk.”[5] Still, many actors aiming to support recovery efforts in Yemen overwhelmingly overlook the degraded environment as a fundamental threat to the country’s future survival, and a new framework that centers the environment as an existential risk to Yemen’s economic recovery and development is urgently required.

Research on environmental and ecological issues and challenges in Yemen is a growing but nascent field. Although terminology such as “environmental safeguarding,” “climate change mitigation and management,” “climate-sensitive programming,” and “creating resilience to climate shocks” are often repeated in development and humanitarian strategies and plans, this has not necessarily led to more nuanced programming aimed at tackling environmental challenges. There remains a substantive need for more analysis and project design on the interaction of environmental degradation, climate destabilization, and political-economic issues in Yemen.

Political ecology offers such a framework and should be central to Yemen’s recovery and development planning. An underrepresented analytical approach, political ecology builds on the tenets of political economy to examine the intersection of environmental, economic, and socio-political factors that affect ecological changes. This paper argues that analyzing Yemen’s development history through a political ecology lens reveals dynamics that must be understood to plan effective recovery assistance. Otherwise, early recovery programming could funnel aid funds for inequitable, ineffective, irrelevant, unsustainable, and — in severe cases — harmful interventions that create or perpetuate the socio-ecological issues that have long characterized Yemen’s relationship with international assistance.

With a focus specifically on agriculture, given its centrality to livelihoods, food security, and the local economy, this paper seeks to contribute to ongoing discussions on improving international interventions in Yemen. It examines and evaluates recent, current, and planned projects developed by international agencies in terms of their consideration of political-ecological factors, and offers recommendations for donors and policymakers, aid agencies and practitioners, conflict negotiators and observers, and agriculture experts and actors.

Methodology

Research for this paper consisted of a desk review of literature and the collection of primary data, which included an online survey, semi-structured key informant interviews and a focus group discussion. The survey targeted 142 respondents across 14 governorates. including farmers, landowners, public servants, researchers, and civil society members (Appendix 1-a) from different agricultural areas (Appendix 1-b). The key informants and focus group participants included international and Yemeni practitioners working in the fields of environmental protection, agriculture, humanitarian aid, and development. Primary research investigated the question: how can a political ecology analytical framework guide aid actors as they design, implement, and adapt contextually attuned, ecologically appropriate, and equitably sustainable recovery programming for the development of Yemen’s agriculture and food systems?

Survey respondents did not include those most vulnerable to environmental impacts, particularly people in rural areas who are in need of support from international interventions. Instead, the inclusion of professionals who work directly with these groups, especially Yemeni experts, aims to represent those at the intersection of political ecology and aid, particularly those working in agricultural development and rural recovery.

Political Ecology Studies and Yemen

Climate researchers increasingly call for analysis of environmental and agrarian change across West Asia,[6] and Yemen presents a case where political ecology can guide aid agencies as they design, plan, and adapt assistance. Formed from intersecting scholarly disciplines in the 1970s, the field of political ecology “combines concerns of ecology and a broadly defined political economy.”[7] Its roots span environmentalism, conservation, and sustainable development. It prioritizes the importance of understanding “access and control over resources,”[8] especially power struggles for “control over the environment,”[9] including but not limited to formal political structures. By evaluating the intertwined political forces (official, informal, traditional, local, global, etc.) at work in environmental change and natural resource distribution, political ecology tracks the ways prosperity and poverty are reinforced for advantaged and marginalized people, respectively. Usually focused on rural areas and populations, political ecology critically frames development issues as processes tied to power, influence, and access — as in political economy — but with a specific focus on human use of natural resources. At its most pragmatic, political ecology is used by researchers to “advocate fundamental changes in the management of nature and the rights of people, directly or indirectly working with state and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to challenge current conditions.”[10]

While a political economy analysis has been used in recent studies of Yemen’s food systems and agriculture challenges,[11] academic understandings of Yemen’s political ecology remain sparse. The limited research that has been published is centered on water resource management. Lichtenthäler’s Political Ecology and the Role of Water in Yemen[12] examines water resource management in the Sa’ada basin using political ecology, framing environmental problems as fundamentally a confluence of the “political and economic context within which they are created,”[13] and not simply the result of a race to consume scarce resources. It critically examines severe groundwater depletion in the basin, caused by intensified irrigation practices, as an outcome of the specific socio-political dynamics between powerful tribal leaders and the central government. Lichtenthäler found that in the absence of formal government regulation, traditional water resource management systems attempted to coordinate the sustainable use of groundwater resources. However, these “indigenous solutions” were not equitable. Landowners who could afford well-drilling and irrigation equipment were also provided subsidies and other advantages through their government ties, allowing them to cultivate water-intensive cash crops, expanding their wealth and dropping the natural level of the water table. Meanwhile, poor farmers suffered from crop failure as wells dried up, causing them to lose further income opportunities. Such imbalances in rural communities, bolstered by tribal elites’ increasing political power and thus, economic wealth, deteriorated the overall “adaptive capacity” of agricultural societies in the Sa’ada basin to mitigate water depletion.[14]

Another study by Moore focuses on how the struggle for control of water resources across Yemen has led to the current water crisis.[15] Arguments over water, primarily for use in irrigation, devastated social and environmental conditions for future development. Framing Yemen’s national water crisis in terms of its political ecology enables Moore, like Lichtenthäler, to posit that government policies promoting groundwater extraction for cash crop cultivation, plus strong patronage systems between the government and rural elites, enabled elites to capture and control water resources, distorting previously sustainable water management practices. He observed that intensive irrigation was also a “key development strategy” proposed by internationally financed agriculture projects, neglecting traditional irrigation technology. This created a “political ecology of exploitation” and marginalization of poor rural households in the process of water extraction for agriculture. While projects intended to “equitably allocate irrigation water,”[16] arrangements between the government and influential landowners ensured massively disproportionate water access.

Political ecology studies of water management in Yemen make it clear that the conflict cannot be untangled from resource scarcity.[17] Thus, conflict resolution recommendations “should be based on an integrated analysis of the conflicts, not only looking at water-related issues but also at the historical, political, institutional, legal and societal context.”[18] This same variegated analysis should be applied to Yemen’s agricultural sector in current and future policy and program design. As concerns over food security, climate change, and a flailing economy come to a head in Yemen, agricultural interventions are seen by many as a panacea. This is a crucial time to apply political ecology insights to design context-specific, tension-reducing interventions. This must begin with an understanding of the history of Yemen’s agricultural development, through the lens of political ecology.

The History of Yemen’s Agricultural Development

As Yemen’s economy was reshaped by globalization in the 1970s, the management of its agricultural and natural resource systems was irrevocably damaged. Understanding Yemen’s agricultural history and mapping historic changes to the environment, including how international interventions have shaped — and continue to shape — the agricultural sector, is essential to contextualize present-day environmental crises, and guide further intervention strategies and project designs that ‘do no harm’ by avoiding the unintended consequences of ill-planned recovery efforts.

Each of Yemen’s diverse agro-ecological zones contains histories of “meticulous knowledge of microclimates [and] engineering feats”[19] among the farmers, pastoralists, and fishermen who steward the land and sea. Before the ‘modern’ agricultural era, Yemen’s rainfed and spate-or natural spring-irrigated terraced fields covered the highlands, producing sturdy and drought-resistant crops such as sorghum, the country’s primary grain, as well as vegetables, fruits, and coffee, some of the few products traded internationally.[20] Farmers and pastoralists were mostly smallholders,[21] with some sharecroppers and wage laborers, and they used water access systems that did not affect groundwater levels.

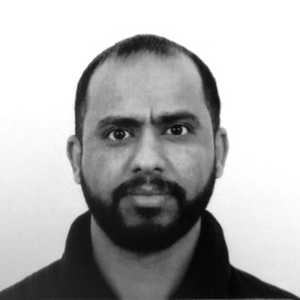

Yemen’s experience in agricultural development— like other countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)[22] — reveals a process that not only failed to sustainably and adequately feed its growing population, but set Yemen on a path to catastrophic food insecurity for the better part of the last decade. In the mid-1960s, 98 percent of Yemen’s staple grains were produced domestically.[23] During the following decades, Yemen’s increasingly remittance- and oil-dependent economy facilitated a fundamental transformation of its agricultural systems and agrarian life, starting a gradual and ultimately devastating devolution from a relatively self-sufficient food system to debilitating dependence on imported food.

One of the biggest impacts on agriculture and rural life in Yemen was the outflow of migrants from the Yemeni countryside to Gulf countries.[24] In 1980, remittances sent home by these workers constituted 40 percent of the gross national product of the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) and 44 percent of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY).[25] This disproportionally large remittance stream “significantly impacted all aspects of life in Yemen.”[26] As the remittance flow increased the incomes of many rural households, it directly funded the modernization of agriculture. Farmers could now afford new technology such as tractors and diesel-powered groundwater pumps. The discovery of oil in 1984 further changed the political economies of the YAR and the PDRY and accelerated modernization of the agriculture sector. At the same time, rainfed agriculture was declining, falling by a third by the 2000s.[27]

In the 1970s-80s, most YAR national agricultural policies were already directed by international firms and development agencies, who urged the government to subsidize fuel and equipment to drill deeper irrigation wells and produce cash crops.[28] Staple grains were replaced with cash crops and overall agricultural production declined.[29] As Yemen became more food import-dependent, it eroded the “economic relevance” of agrarian society producing food for consumption.[30]Subsidies for grain imports kept staple food prices low for Yemeni consumers, which neglected and disincentivized local grain producers,[31] and augmented the economic domination of powerful import sector conglomerates.[32]

This supply-side shift, along with demand-side emergence of more households with more disposable income, and expanded road networks that made transport easier, created the conditions for greater qat production. Qat chewing became a “potent symbol of being Yemeni,” distinct from other Gulf and Arab countries, which had banned the stimulant.[34] Authorities tend to avoid the issue of qat, but it continues to dominate the domestic Yemeni agricultural economy and ecology,[35] accounting for 40 percent of all agricultural water consumption.[36] Qat’s huge profit margins (around 80 percent) make it 10-20 times more profitable for producers than “most competing crops.”[37]

Unsustainable Practices

A succession of society-altering events in the 1990s reinforced Yemen’s socio-environmental instability. This began with the unification of the YAR and PDRY into the Republic of Yemen on May 22, 1990. In 1991, three-quarters of a million Yemenis returned from living and working abroad,[38] accelerating migration from rural to urban areas as skilled laborers pursued careers outside of agriculture.[39] Meanwhile, the integration of PDRY and YAR agricultural policies led to the further expansion of cash crop production. The government’s neglect of ancient irrigation and agricultural technologies, coupled with easy access to groundwater, were among the key factors that damaged traditional water harvesting and agricultural practices like mountain terraces. Urbanization and road construction also encouraged rural-urban migration and accelerated the shift in agricultural and irrigation practices.[40]

After the 1994 civil war, international aid for reconstruction was tied to the government’s adoption of neoliberal economic reforms, including sharp cuts to food and fuel subsidies.[41] Prescribed by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, these measures were considered successful in terms of the stated desired outcomes: the state budget deficit and spending both decreased, as did inflation. But this did not translate into improvements for the average Yemeni. The structural changes came at “heavy social and economic costs” including increased unemployment and poverty, and weakening local purchasing power to buy food that was increasingly imported.[42] Yemen’s Social Fund for Development (SFD) was established in 1997 in part to soften impacts at the household level.[43]

These reforms also did nothing to reduce unsustainable groundwater extraction. Agricultural activities continued to focus on cash crop production, aiming to stimulate the export of high-value fruits and vegetables; qat cultivation was further boosted. This extractive form of agriculture also bolstered wealthy rural elites, who had already benefited from concentrated land ownership.[44] It expanded and intensified drilling into aquifers that could not refill sufficiently, harming sustainable irrigation practices.[45] Development projects also reorganized traditional spate irrigation systems, which benefitted upstream users while cutting off access for downstream users.[46]

Overall, the modernization of the agricultural sector contributed to economic stratification in rural communities and a host of socio-environmental issues and factors that intersect with the economy – which is at the heart of a political ecology analysis of Yemen’s complicated and turbulent agrarian changes. Historically, international aid agencies have fallen short by inadequately researching the dynamics around interventions, in part because experts discount Yemen’s historical experience and local knowledge. Investments in agricultural programs by international agencies, “after decades of neglect,” tended to ignore how earlier policies contributed to the current problems.[47] There has also been a general failure to emphasize the link between food import dependence and the decline in agricultural production when studying the causes of food insecurity in Yemen.[48]Specifically, the macroeconomics of Yemen’s food import sector have been neglected in interventions; the sector is dominated by a small group of private conglomerates that are unlikely to prioritize increasing domestic production over profits, including those from imports by humanitarian organizations for mass food distributions.[49]

Environmental Fallout

The impacts of Yemen’s climate breakdown are being experienced by everyday Yemenis, and every indicator of climate destabilization has disastrous effects on agriculture. These are often read as ‘natural’ knock-on effects of global climate change; in fact, societal shifts, weak or absent governance, and inappropriate development planning over the last 50 years created the present environmental crisis. The ongoing conflict introduced new devastating factors that have worsened conditions, especially for the agriculture sector. These include lost agricultural land, livelihoods, and knowledge due to displacement;[50] agricultural areas strewn with mines and harmful war debris; and the targeted destruction of agricultural infrastructure.[51]

The effects of climate change have severely exacerbated these crises, and will continue to do so. Research has highlighted a host of problems due to climate variability in Yemen as a result of climate change that affects the agriculture sector.[52] This includes a widespread water crisis due to aquifer exhaustion and groundwater depletion; increasing rainfall variability, resulting in floods that destroy crops, livestock, and infrastructure, and wash away topsoil that would otherwise help retain groundwater; an expected increase in droughts, which will degrade agricultural land and increase desertification;[53] more frequent and severe extreme weather events, such as cyclones and storms,[54] that cause landslides and lead to insect infestations; and higher temperatures, with more variability.[55] As climate destabilization further disrupts Yemeni society and the economy, social tensions between resource users will likely rise. More people are also expected to migrate from rural to urban areas, and further afield, as worsening conditions force displacement.[56]

A political ecology view of Yemen’s agricultural and environmental history underlines the dynamics that created its current socio-environment. These are key for international aid actors to study, especially when planning agricultural interventions.

Internationally Led Strategies: On Paper and in Practice

With international aid systems turning more attention to environmental issues and the global impacts of climate change, a number of strategies, frameworks, and tools have been rolled out. However, these top-down efforts are often not meaningfully localized nor synchronized with national strategies, leaving internationally led climate strategies disconnected from their implementation.

The European Institute of Peace recently carried out the largest consultative survey coordinated in Yemen in recent years, querying 16,000 Yemenis across nine governorates about their “needs, perspectives and rights.”[57] The survey found that in eight of the nine governorates, people prioritize environmental issues as their most urgent or second-highest concern (ending the conflict was usually first). Only in Hudaydah was the environment not one of the top two priorities; however, community dialogues in the governorate repeatedly highlighted the risk of environmental disaster posed by the Safer oil tanker.

Yemeni aid workers report that they have begun raising concerns about environmental issues more frequently within their organizations.[58] They list examples such as worsening floods that destroy livelihoods and dislodge unexploded ordnance; increased depletion of groundwater as more people turn to qat production (qat remains a reliable source of income in a floundering economy); and deforestation due to the ongoing economic crisis, as people without stable income sources can no longer afford cooking gas and are switching to wood-fired stoves.

Through a review of key strategy documents, complemented by key informant interviews with aid workers, a focus group discussion with Yemeni development and agriculture experts, and findings from a survey, this section provides an overview of recent development efforts and grounds them in reality, aiming to acknowledge the positive direction internationally led strategies are taking in Yemen and offer insights to strengthen their implementation in a more socio-ecologically equitable manner.

Environmental Considerations in Humanitarian and Development Interventions

Development initiatives in Yemen have been largely unchanged by the war, with most plans still resembling the livelihoods projects designed for pre-2015 Humanitarian Response Plans.[59] Many have had only minimal updates to factor in environmental concerns. However, key agencies have recently increased their environmental focus, as climate-oriented frameworks and strategies circulating on a global level have been adapted for Yemen.

The UN’s Common Country Analysis (CCA)[60] shapes most UN agency plans and strategies by mapping Yemen’s progress and obstacles on the path to achieving global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The CCA’s overview of Yemen’s main issues includes “environment and climate change.” However, rather than framing Yemen’s complex ecological challenges — called a ‘crisis within a crisis’ — as existential and foundational, these are presented as a laundry list of environmental issues, most of which are related to agriculture.[61] Another section focused on the catastrophic environment risk posed by the FSO Safer vessel. The CCA’s “resilience” section importantly mentions the government’s inability, alongside “traditional social institutions,” to regulate water rights and usage, particularly between wealthier farmers and smallholders, and especially for water-intensive crops. But in highlighting the need to increase local agricultural production to improve food security and reduce reliance on imports, the analysis overlooks factors associated with scaling up production, such as market competition from imported staple grains, the dominance of import conglomerates, or the shortage of alternative crops with a realistically “comparable” profit to qat.

The UN Yemen Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework for 2022-2024[62] is built upon the CCA, and prioritizes “food security and livelihoods” and “environmental stability” as desired outcomes within the frameworks’ theory of change, while climate change cuts across all components. While the needs analysis neglects the systemic root causes of food insecurity and increased water scarcity in Yemen, the framework does recommend developing policies and legislation for “sustainable climate-sensitive environmental management.” Its main intervention strategies include agricultural value chain diversification, development of a water information system, strengthening climate change mitigation through disaster risk reduction, and safeguarding the natural resources to reduce local conflicts, with a focus on women, youth, and vulnerable populations. Fieldworkers in Yemen should closely follow the results of the UN evaluation when it is completed in 2024, to monitor actual on-the-ground commitment to these environmental priorities.

Another noticeable step forward is the inclusion of climate and environmental concerns in the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ (OCHA) first ‘Strategic Objective’ in the latest Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP), which calls for efforts to “reduce the adverse effects of climate change and natural and human-made disasters.”[63] While the primary response strategy is limited to one-off provisions of in-kind food, basic emergency kits, or small cash transfers, the newly expanded humanitarian-development-peace nexus in the HRP builds a theoretical space for expanding the technical scope of climate and environmental responses.

In 2023, the World Food Programme (WFP) launched a mandatory Environmental and Social Risk (ESR) screening tool that all partners must use to inform and improve project design and guide implementation, including food basket distribution — its largest and most costly operation. Application of the tool, however, appears to require partners’ time to conduct the ESR as an “investment,”[64] since WFP resources are not provided to do so. An implementing partner also accuses WFP staff of focusing disproportionately on minor environmental issues, such as plastics used in disbursements, where very few alternatives exist.[65] WFP has also reportedly launched a small fund for sustainable livelihood projects, including for agriculture, designed with significant input from local partners, including sustainable water use practices, and project plans that strengthen value chains for specialty products such as beekeeping and coffee. But local partners are worried that WFP may — like other agencies — fail to adequately fund the structures required to carry out a technically sound project.[66]

The World Bank, another major multinational actor in Yemen, only nominally mentioned climate change and environmental impacts in its 2022-2023 Country Engagement Note.[67] However, its initiatives show practical commitment to environmental considerations. For example, the Yemen Food Security Response and Resilience Project (FSSRP) – a four-year US$127 million project funded by the World Bank and managed by the UN Development Programme (UNDP), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the WFP – includes several highly relevant activities, including rehabilitation and maintenance of terraces, rain harvesting installations, and “economically-environmentally friendly” practices such as climate-smart agriculture and the use of hydroponics. The key Yemeni partners for the FSRRP, the SFD and the Public Works Project, have long been considered effective development actors, and experts have praised their institutional memory, the impact of their projects, and their adoption of social and environmental studies. The Small and Micro Enterprise Promotion Service (SMEPS), an SFD subsidiary, reported receiving capacity-building support from the UN agencies they partner with, and positive reception from project ideas that were built based on close consultations with local communities.[68]

A rigorously environmentally centered document, the Environment and Social Management Framework (ESMF)[69] provides guidance for implementing partners on assessing negative project-related environmental and social impacts and measures to avoid them. It also builds on existing Yemeni governmental policies and strategies, a tactic mostly overlooked by other development actors, while carefully noting gender and conflict considerations throughout. The ESMF thoroughly screens components of the FSRRP, such as agricultural production, livestock and fishing, nutrition and food security, against seven of the World Bank’s Environmental and Social Standards (ESS). Upon project commencement, an Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) will be prepared for each subproject, including a set of proposed mitigation measures to address environmental and social risks and impacts initially identified by the overall project-level Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA). For high-risk subprojects, an ESIA is required in line with Yemen’s 1995 Environment Protection Law; a “simple” ESIA is also required for moderate-risk subprojects. World Bank implementing partners, managed by UNDP, confirmed in interviews they must complete an ESS checklist before each project, through consultations with community members, and prepare a mitigation plan for identified potential environmental risks, which is then agreed with community groups.[70] Overall, the ESMF is a commendable analytical effort notably missing in similar UN development projects. For instance, Enhancing Rural Resilience in Yemen (ERRY),[71] a joint program by the UNDP, FAO, WFP, and International Labour Organization, which supports “clean energy solutions, environmental protection, and climate adaptive capacity,”[72] lacks environmental risk analyses and management plans.[73]

However, World Bank partners cautioned that some analyses do not capture all relevant risks because of short, “emergency” deadlines.[74] Similarly, a study on disaster risk reduction in Yemen[75] found that the majority of projects centered around water-related disasters were “emergency solutions.” Likewise, the consultative process to prepare the ESMF was done at the “central level due to the ‘emergency nature of the project and unique requirements under emergency circumstances.’” When deeper analyses were done, such as the ESIA, these were still “very quick” because of the “emergency,”[76] which prevents implementers from fully understanding the range of converging factors relevant to the project, including the conflict, economic crisis, and socio-political dynamics. Often, such rigorous studies at the local level take at least three to six months, plus funding for external consultants to conduct them.[77] Interviews highlighted the importance of contracting experienced, knowledgeable third parties to carry out analysis prior to project implementation and monitoring during projects to avoid a conflict of interest.[78] But most implementing organizations don’t have sufficient funding to hire such experts, including World Bank and UNDP partners, who noted they are “still fighting” for funding to hire consultants, conduct relevant technical assessments, continue community engagement, and to comprehensively implement mitigation strategies or the ideas and knowledge they gained through environmental safeguarding training.[79] One aid worker remarked that environmentally conscious solutions are unlikely to be cost-efficient, but that “perhaps that calculation needs to change.”[80]

The progressive partnership practices between the World Bank, UNDP, and their local implementing partners are the exception, not the rule, according to interviewees.[81] The majority of donors do not require an environmental assessment,[82] including the Yemen Humanitarian Fund, which receives and disburses relief funds and manages HRP implementing partners. Civil society organizations, especially those working in environmental protection, also reportedly lack the financial support to be effective at scale. One interviewee noted that the perceived lack of technical capacity, and real lack of funding, means local organizations and local experts are overlooked by international actors when seeking implementing organizations to partner with, despite their deep knowledge of local environments.[83] Donors must understand that their projects should be based on comprehensive studies, and that their funding holds real power, as it can influence local authorities to permit such studies. As these new policies and practices take shape in Yemen, it is important to keep them grounded in reality by accurately assessing local capacities, monitoring local experiences, and overcoming time constraints and limited funding.

Local Perceptions of Agricultural Development Projects

Going forward, project planning should better account for Yemen’s diversity and wide range of distinct ecologies and traditions. Informants noted that international specialists have historically arrived with presumptions about Yemen’s food and agriculture systems, discounting Yemeni agricultural knowledge. More recently, international actors have imported practices from other countries unsuccessfully. In one agricultural specialist’s experience, a new type of sorghum — Yemen’s most popular grain — was introduced by a research program. But the crop could not be used for fodder or food, as indigenous sorghum could, reducing overall profitability.[84] A different organization provided support to farmers who used pesticides in their fields, which killed local honeybees, affecting honey production.[85] Another project, a contentious dam construction, was launched without consulting the farmers in the surrounding area, nor residents living downstream in the nearby valley, causing tension between neighboring communities, as upstream farmers vied for water access to use for qat production.[86]

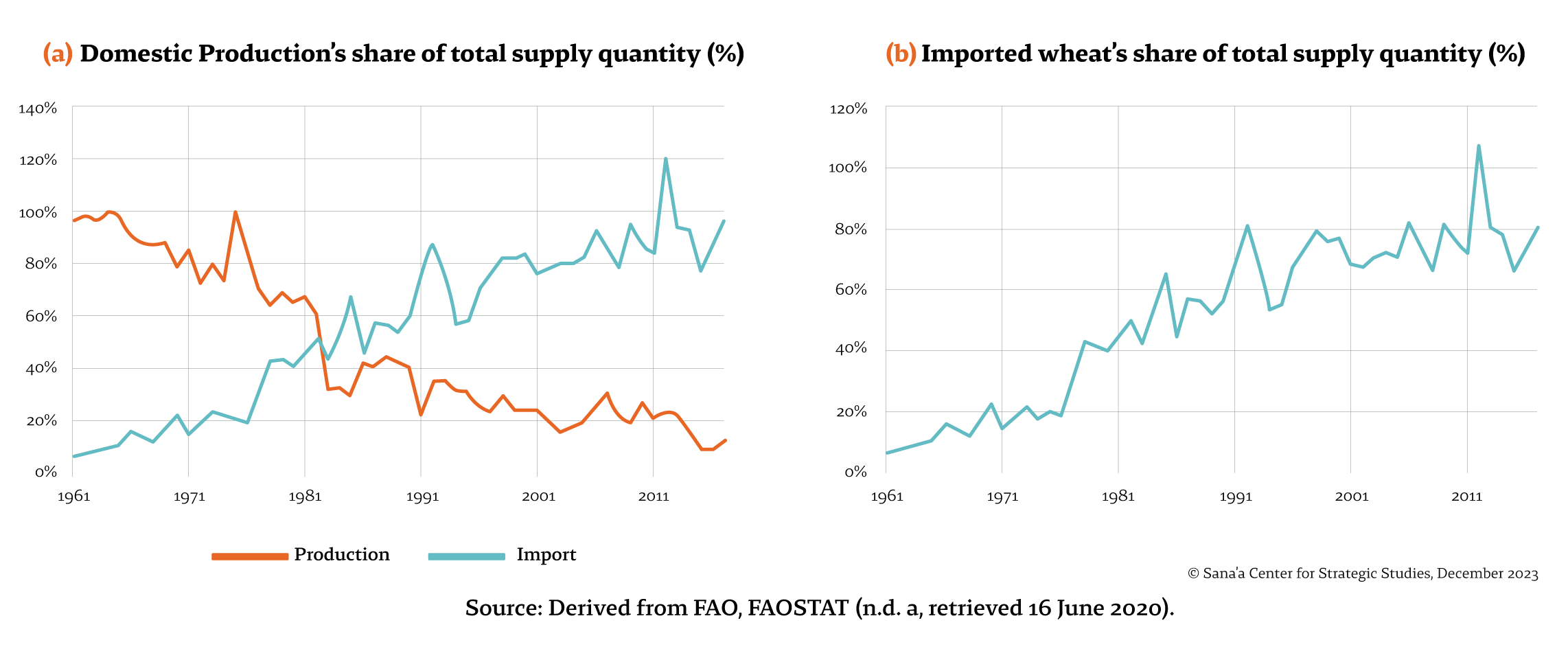

Survey results provide additional insights into the history of agricultural development projects undertaken in 14 governorates.[87] Data shows that the majority of the respondents, 105 of the 142 people surveyed, are not currently benefiting from any agricultural development initiatives. This may indicate a general lack of such interventions. Although a smaller number of agricultural projects were active at the time of the survey, 65.5 percent of all respondents could recall active or past agricultural projects, providing valuable insights into local perceptions of projects, including needs assessments and stakeholder identifications, tensions or conflicts regarding land or water resource control, incorporation of local knowledge and practices, and the overall success of these projects.

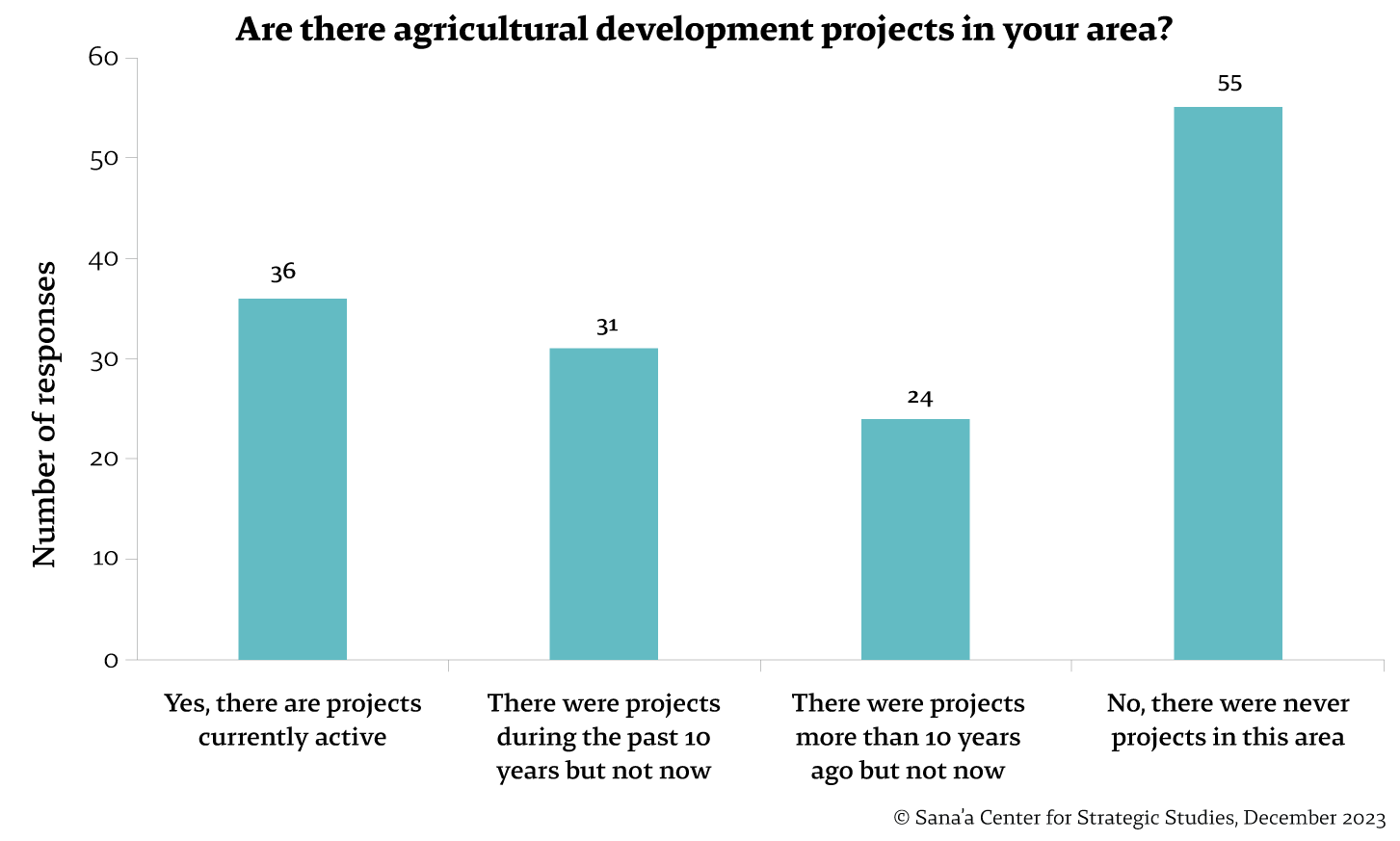

Respondents who reported active or past projects were asked about key factors related to project planning and implementation. Their responses reveal several repeated weaknesses in project design and implementation, which suggest a failure to properly understand local contexts and the potential impact of project outcomes. The majority of respondents (51 percent) felt that project staff either made insufficient assessments or did not assess local needs and main stakeholders, particularly regarding land and water resources (Figure 3a). Only 29.4 percent felt a thorough assessment was conducted, indicating that there is room for improvement before projects are truly responsive to community needs and preferences.

Similarly, when asked whether project staff identified any tensions or conflicts regarding land or water resource control and access, 52.9 percent responded that project staff did not conduct an assessment or inadequately assessed land and water access problems (Figure 3b). Only 22.4 percent thought project staff thoroughly assessed these factors, indicating a need to pay closer attention to the potential conflicts that may arise from interventions and carefully plan measures to mitigate them.

In terms of the incorporation of local knowledge and practices, 40 percent of respondents thought the projects incorporated some local knowledge or practices, while just 29.4 percent believed that the projects significantly incorporated local knowledge and practices, and a sizable minority (10.6 percent) believed no such integration occurred (Figure 3c). Meaningful incorporation of local knowledge and practices can help ensure projects are more contextually appropriate and sustainable in the long term. The failure to use existing local expertise is a missed opportunity.

While progress is being made, improvements are still needed to fully optimize projects’ intended benefit. When asked about perceptions of the overall success of projects, 72.9 percent of respondents believed they were somewhat successful, while only 18.8 percent believed they were very successful (Figure 3d). This suggests that project staff should engage more consistently and meaningfully with the local community, earnestly addressing potential conflicts to improve overall project success and fully incorporating local knowledge and practices.

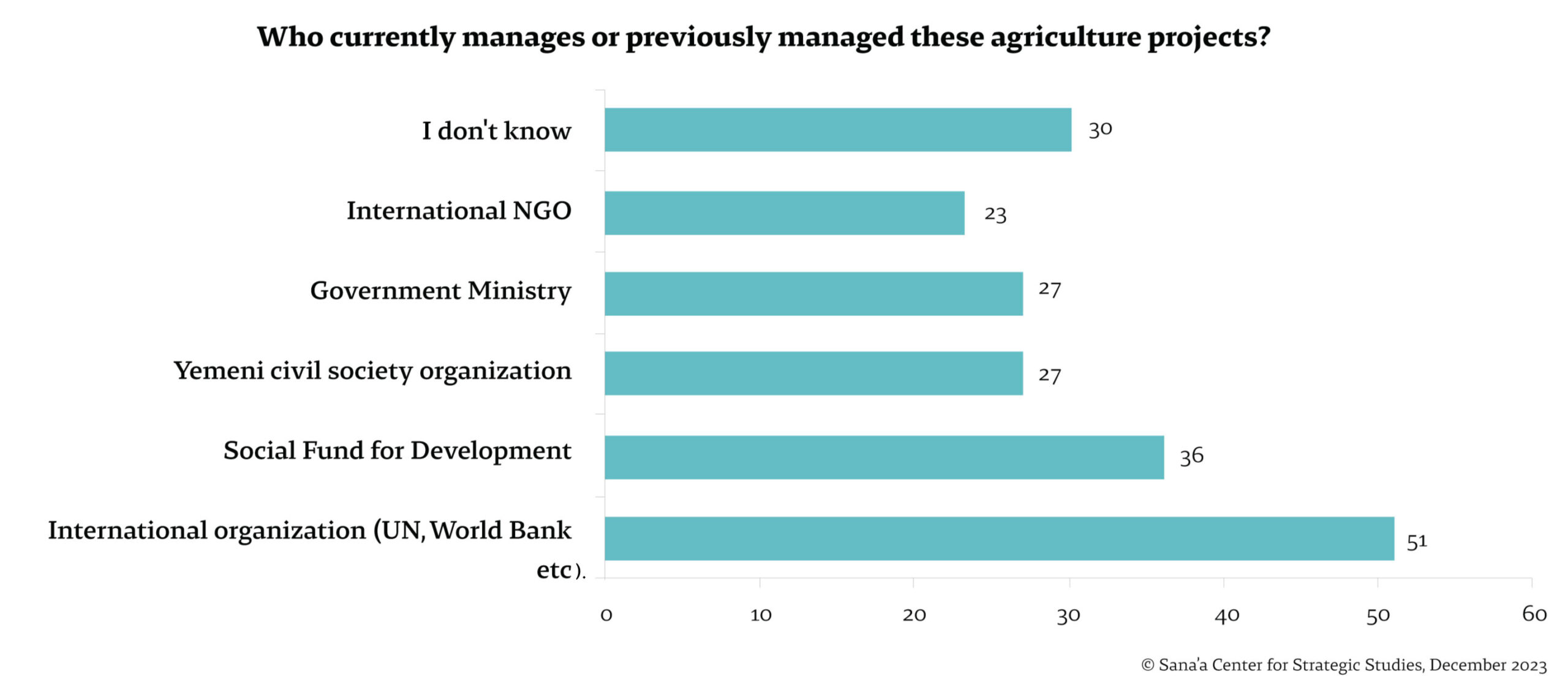

While this survey provides a glimpse of local impressions of agriculture projects, it is important to note that these results aggregated all interventions, in a broad continuum from international and local actions to government interventions (Figure 4). To assess the performance of a specific actor, more focused studies with beneficiaries and local community representatives would be required. More details about the results of this survey can be found in the appendixes, including a cross-index of different questions (Appendix 3).

Recommendations

Since Yemen’s first Humanitarian Response Plan, released over a decade ago,[90] urgent calls for emergency assistance in Yemen have overshadowed the quieter crises related to the economy and ecology. Now that analysis of the economy and aid has gained more traction, attention must simultaneously be given to rigorous ecological analysis, looking toward environmental equity and sustainability as pillars of sustainable development. As progress toward SDGs is pursued, international actors would benefit from the critical analysis offered by political ecology, which examines the inherently political and power-based dynamics in which development has impacted Yemen’s resources, society, and economy. Political ecology offers an analytical framework for international actors investing in Yemen’s recovery to intervene meaningfully and minimize potential harm by adequately scrutinizing the often-complex local context in which policy and practice operate and impact the socio-environment.

This paper calls for recovery efforts to be environmentally conscious, ecologically restorative, and economically and socially equitable, particularly for agriculture and food system interventions. By thoroughly studying the hyper-local historical and present contexts, interventions can be delivered according to local designs. The following recommendations are based on this paper’s research findings and are in line with the small but growing wealth of specific environmental advice from researchers,[91] highlighting agricultural improvements.

For donors and policymakers, on funding and research:

- Donors should adequately fund comprehensive studies and allocate time for locally developed project design.

- Donors should require socio-environmental analysis and adequately fund risk assessments, safeguards, and monitoring.

- Policymakers should prioritize multi-year, bottom-up, iterative programs that allow projects to test solutions, learn, and adjust based on evaluations and community input, and reproduce scaled-up phases without legal repercussions of program performance failure. This practice is being adopted in development spheres and could be transformative in Yemen.

- Donors and policymakers should enhance, guide, and facilitate coordination between the multiple analytical agencies working on Yemen who have the capacity to carry out necessary studies and complementary core strengths, and adequately fund them to underpin and enhance operational organizations.

- Donors should pressure authorities to allow access for more data collection activities, particularly for socio-environmental research and assessments.

For aid agencies and practitioners, on research and programming:

- Aid agencies and practitioners should comprehensively study Yemen’s localized political ecologies, including historical experience, hyper-local agroecological profiles, micro-economic features, socio-political dynamics (including powerful and marginal stakeholders), resource control and regulations (both official and traditional), local knowledge, experience, and perceptions of equitability and sustainability.

- Aid agencies should demonstrate commitment to consistent and meaningful local leadership and equitable partnerships that enable food system accountability.[92]

- Humanitarian and development actors should facilitate regular cross-learning, with local actors and civil society members to better understand and address the implications of agricultural development, environmental crisis, and climate change.

- Aid agencies should encourage culturally sensitive education on awareness of socio-environmental safeguarding practices and enforcement mechanisms.

For conflict negotiators and observers, on peace pathways and a just transition:

- Conflict negotiators should integrate socio-environmental concerns into peacebuilding efforts in Yemen, alongside incorporation of economic issues to address the economic system collapse.[93], [94] Additional studies are needed to understand the potential for environmental and climate topics to advance conflict resolution.[95]

- Conflict negotiators and peacebuilding actors should carefully consider environmental injustice, prioritizing a just transition in aid.[96] They should invest in agricultural production and socio-environmental solutions, but avoid framing future ‘climate conflicts’ as inevitable.

For international and local agriculture experts and actors, on the food and agriculture system:

- Agriculture experts should promote an ecologically sensitive, socio-economically attuned agricultural sector with sustainable practices, specifically feasible in agro-ecological zones.

- Agriculture experts should carefully and continuously evaluate the socio-environmental consequences of increased investment in local food production, balancing export and subsistence sectors, and avoiding socio-economic stratification, conflict, and ecological degradation through contextually based regulation of natural resources.

- Agricultural organizations should implement locally designed and driven social change campaigns regarding environmental safeguarding, and incentives for economically viable qat production alternatives that are sensitive to the socio-cultural realities.

- Agriculture experts should study the history of legal and community-based regulations for water and land resource management to complement national regulatory frameworks and enforcement.

- Leaders in agriculture should test, adopt, and expand new technology, while weighing positive and potential negative effects and avoiding over-reliance on technology-reliant climate adaptations for agricultural production that risk perpetuating negative externalities such as those Yemen’s agricultural system experienced after mechanization.

This paper was produced as part of the Applying Economic Lenses and Local Perspectives to Improve Humanitarian Aid Delivery in Yemen project, funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

- OCHA, “Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan 2023,” January 25, 2023, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-humanitarian-response-plan-2023-january-2023-enar

- Niku Jafarnia, “Risking the Future: Climate Change, Environmental Destruction, and Conflict in Yemen,” Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC), October 4, 2022, https://civiliansinconflict.org/risking-the-future-climate-change-environmental-destruction-and-conflict-in-yemen/

- Sherri Goodman and Pauline Baudu, “Climate Change as a ‘Threat Multiplier’: History, Uses and Future of the Concept,” The Center for Climate and Security, January 3, 2023, https://climateandsecurity.org/2023/01/briefer-climate-change-as-a-threat-multiplier-history-uses-and-future-of-the-concept/#:~:text=The term was coined in,to contribute to security risks.

- Taylor Hanna, David K. Bohl, and Jonathan Moyer, “Assessing the Impact of War in Yemen: Pathways for Recovery,” UNDP, November 23, 2021, https://www.undp.org/yemen/publications/assessing-impact-war-yemen-pathways-recovery; Sarah Vuylsteke, “When Aid Goes Awry: How the International Humanitarian Response is Failing Yemen,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 27, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/reports/humanitarian-aid; “Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation of the Yemen Crisis (2022),” Inter Agency Standing Committee, July 14, 2023, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/inter-agency-humanitarian-evaluation-iahe-yemen-crisis

- Helen Lackner and Abdulrahman Al-Eryani, “Yemen’s Environmental Crisis Is the Biggest Risk for Its Future,“ The Century Foundation, December 14, 2020, https://tcf.org/content/report/yemens-environmental-crisis-biggest-risk-future/

- Roland Riachi, “Political Ecology of Food Regimes and Waterscapes in the Arab World,” Arab Reform Initiative, September 23, 2021, https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/environmental-politics-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa-proceedings-from-first-inaugural-conference/

- Piers Blaikie and Harold Brookfield, Land Degradation and Society, (London, Routledge, 1987). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315685366

- Michael Watts, “Intellectual Origins of Political Ecology,” A Companion to Economic Geography, (Blackwell Publishing, New Jersey, 2003), pp. 257-274. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9780470693445

- Raymond L. Bryant and Sinéad Bailey, Third World Political Ecology, (London: Routledge, 1997). https://www.routledge.com/Third-World-Political-Ecology-An-Introduction/Bailey-Bryant/p/book/9780415127448

- Paul Robbins, Political Ecology: A Critical Introduction, 3rd Edition, (Wiley-Blackwell: New Jersey, 2019) https://www.wiley.com/en-ae/Political+Ecology:+A+Critical+Introduction,+3rd+Edition-p-9781119167440

- Martha Mundy and Frederic Pelat, “The Political Economy of Agriculture and Agricultural Policy in Yemen,” in The Political Economy of Agriculture and Agricultural Policy in Yemen (Berlin: Gerlach Press, 2015), pp. 98 – 122 https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1df4hh0; Martha Mundy, Amin Al-Hakimi, Frédéric Pelat, “Neither security nor sovereignty: the political economy of food in Yemen,” in Food security in the Middle East (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 135–158 https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199361786.003.0006

- Gerhard Lichtenthäler, Political Ecology and the Role of Water in Yemen, (London: Routledge, 2003). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315246550

- Bryant and Bailey, Third World Political Ecology, p.28

- Gerhard Lichtenthäler, Political Ecology and the Role of Water in Yemen, (London: Routledge, 2003). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315246550

- Scott Moore, “Parchedness, Politics, and Power: The State Hydraulic in Yemen,” Journal of Political Ecology, pp. 38-47, 2011, https://journals.librarypublishing.arizona.edu/jpe/article/id/1838/

- Moore, “Parchedness, Politics, and Power,” p.43

- Gerhard Lichtenthäler, “Power, Politics and Patronage: Adaptation of Water Rights among Yemen’s Northern Highland Tribes,”, Études Rurales, pp. 155-156, 2000, https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesrurales.20

- Patrick Huntjens, Rens de Man, Adel Al-Weshali, Nadwa Al-Dawsari, Abdullah Al-Kinda, Mohamed Al-Suneidar, “The Political Economy of Water Management in Yemen: Conflict Analysis and Recommendations,” The Hague Institute for Global Justice, 2014, https://thehagueinstituteforglobaljustice.org/the-political-economy-of-water-management-in-yemen Patrick Huntjens, Rens de Man, Adel Al-Weshali, Nadwa Al-Dawsari, Abdullah Al-Kinda, Mohamed Al-Suneidar, “The Political Economy of Water Management in Yemen: Conflict Analysis and Recommendations,” The Hague Institute for Global Justice, 2014, https://thehagueinstituteforglobaljustice.org/the-political-economy-of-water-management-in-yemen

- Max Ajl, “Yemen’s Agricultural World: Crisis and Prospects,” Crisis and Conflict in Agriculture, 2018, https://www.cabi.org/environmentalimpact/ebook/20183269694

- Daniel Martin Varisco, “Agriculture in the Northern Highlands of Yemen: From Subsistence to Cash Cropping,” Journal of Arabian Studies, March 19, 2019, https://epub.oeaw.ac.at/?arp=0x0039b10b

- A small-scale farm, often operated by a family, often employs farming methods which are very different from industrial agriculture. Smallholders may own or lease the land they operate, and usually produce a mixture of subsistence and cash crops.

- Riachi, “Food Regimes and Waterscapes,” p. 8-9

- Zaid Ali Basha, “The Agrarian Question in Yemen: the National Imperative of Reclaiming and Revalorizing Indigenous Agroecological Food Production,” The Journal of Peasant Studies, January 27, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2021.2002849

- Najwa Adra, 1983. “The Impact of Male Outmigration on Women’s Roles in Agriculture in The Yemen Arab Republic” The Inter-country Experts Meeting on Women in Food Production, October 1983, revised January 2013, http://www.najwaadra.net/impact.pdf

- Nader Fergany, “The Impact of Emigration on National Development in the Arab region: the Case of the Yemen Arab Republic,” International Migration Review, 1982, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12265310/

- Adra, “Impact of Outmigration,” p. 27

- Helen Lackner, “Global Warming, the Environmental Crisis and Social Justice in Yemen,” Asian Affairs, November 19, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1080/03068374.2020.1835327

- Martha Mundy, “The future of food and challenges for agriculture in the 21st Century – The war on Yemen and its agricultural sector,” ICAS-Etxalde Colloquium, April 2017, http://elikadura21.eus/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/50-Mundy.pdf

- Edward Thomas “ Food security in Yemen: the role of the private sector in promoting domestic food production”, p. 8-28, February 2022. https://odi.cdn.ngo/media/documents/Food_security_in_Yemen_2_-_the_role_of_the_private_sector_in_promoting_domesti_oHhlb93.pdf”

- Adra, “Impact of Outmigration,” p. 58

- Christopher Ward, “The Political Economy of Irrigation Water Pricing in Yemen,” The Political Economy of Water Pricing Reforms, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp.381-394, https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20001809845

- Edward Thomas “ Food security in Yemen: the role of the private sector in promoting domestic food production”, p. 8-28, February 2022. https://odi.cdn.ngo/media/documents/Food_security_in_Yemen_2_-_the_role_of_the_private_sector_in_promoting_domesti_oHhlb93.pdf” .

- After Zaid Ali Basha, “The Agrarian Question in Yemen: the National Imperative of Reclaiming and Revalorizing Indigenous Agroecological Food Production,” The Journal of Peasant Studies, January 27, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2021.2002849

- Varisco, “Agriculture in the Northern Highlands of Yemen,” p. 187

- Laura Kasinof, “Qat in Wartime: Yemen’s Resilient National Habit,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, March 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/march-2023/20009

- Basha, “Agrarian Question,” p. 1398-1420

- Patrick Huntjens, Rens de Man, Adel Al-Weshali, Nadwa Al-Dawsari, Abdullah Al-Kinda, Mohamed Al-Suneidar, “The Political Economy of Water Management in Yemen: Conflict Analysis and Recommendations,” The Hague Institute for Global Justice, 2014, https://thehagueinstituteforglobaljustice.org/the-political-economy-of-water-management-in-yemen Patrick Huntjens, Rens de Man, Adel Al-Weshali, Nadwa Al-Dawsari, Abdullah Al-Kinda, Mohamed Al-Suneidar, “The Political Economy of Water Management in Yemen: Conflict Analysis and Recommendations,” The Hague Institute for Global Justice, 2014, https://thehagueinstituteforglobaljustice.org/the-political-economy-of-water-management-in-yemen

- During the 1991 Gulf Crisis, more than three-quarters of a million Yemenis were forced out of Saudi Arabia as retaliation for the Yemeni government’s stance on the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. A subsequent suspension of Western and Gulf aid, also in response to the Yemeni government’s position, significantly disrupted the economy.

- Nader Fergany, “Structural Adjustment versus Human Development in Yemen,” in Yemen into the Twenty-First Century: Continuity and Change, (Ithica Press, March 1, 2007), https://www.scribd.com/book/353208466/Yemen-into-the-Twenty-First-Century-Continuity-and-Change

- Musaed Aklan, Charlotte de Fraiture, Laszlo G. Hayde, Marwan Moharam, “Why Indigenous Water Systems are Declining and How to Revive Them: A Rough Set Analysis,” Journal of Arid Environments, July 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2022.104765

- Peter Salisbury, “Bickering While Yemen Burns: Poverty, War, and Political Indifference,” Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, June 27, 2017, https://agsiw.org/bickering-while-yemen-burns-poverty-war-and-political-indifference

- Nora Ann Colton, “Yemen: A Collapsed Economy,” Middle East Journal, 2010, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40783107?seq=1

- Sheila Carapico, “No Quick Fix: Foreign Aid and State Performance in Yemen. Center for Global Development,” Center for Global Development, https://scholarship.richmond.edu/polisci-faculty-publications/33/

- Lackner, “Environmental Crisis in Yemen,” pp. 859-874

- Lackner and Al Eryani, “Yemen Environment Risk for Future,” pp. 2-5

- Adel Al-Weshali, Omar Bamaga, Cecilia Borgia, Frank van Steenbergen, Nasser Al-Aulaqi, Abdullah Babaqi, “Diesel Subsidies and Yemen Politics: Post-2011 Crises and their Impact on Groundwater Use and Agriculture,” Water Alternatives, 2015, https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol8/v8issue2/288-a8-2-11/file

- Mundy, “Future of Food” pp. 2-18

- In 2010, WFP’s Comprehensive Food Security Survey determined that food insecurity resulted from links between poverty, population growth, and insufficient food supply – neglecting the dynamics around the “insufficient” staple grain supply. “Comprehensive Food Security Survey 2010,” World Food Programme, March 2010, https://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/ena/wfp219039.pdf

- Almost 15% of all food imports in 2020 went to food aid distributions. Thomas, “Food Security Yemen,” p. 8-28.

- Basha, “Agrarian Question,” pp. 1398-1420; Ajl “Arab Region’s Agrarian Question,” pp. 955-983;

- Martha Mundy, “The Strategies of the Coalition in the Yemen War: Aerial Bombardment and Food War,” World Peace Foundation, October 9, 2018, https://sites.tufts.edu/wpf/strategies-of-the-coalition-in-the-yemen-war/; Jeannie L Sowers, Erika Weinthal and Neda Zawahri, “Targeting Environmental Infrastructures, International Law, and Civilians in the New Middle Eastern Wars,” Security Dialogue, October 2017, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26294229

- Manfred Wiebelt, Clemens Breisinger, Olivier Ecker, Perrihan Al-Riffai, Richard Robertson, Rainer Thiele, “Climate Change and Floods in Yemen Impacts on Food Security and Options for Adaptation,” The International Food Policy Research Institute, December 2011, https://www.ifpri.org/publication/climate-change-and-floods-yemen-impacts-food-security-and-options-adaptation

- Lackner and El-Iryani, “Yemen Environment Risk for Future,” pp. 2-5

- Yasmeen Al-Eryani, “Yemen Environment Bulletin: How Weak Urban Planning, Climate Change and War are Magnifying Floods and Natural Disasters,” Sana’a Center For Strategic Studies, July 14, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/10346 Yasmeen Al-Eryani, “Yemen Environment Bulletin: How Weak Urban Planning, Climate Change and War are Magnifying Floods and Natural Disasters,” Sana’a Center For Strategic Studies, July 14, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/10346

- Hadil Mohamed, Moosa Elayah, Lau Schuplen, “Yemen between the Impact of the Climate Change and the Ongoing Saudi Yemen War: A Real Tragedy,” Centre For Governance and Peacebuilding Yemen, 2017, https://www.kpsrl.org/publication/yemen-between-the-impact-of-the-climate-change-and-the-ongoing-saudi-yemen-war-a-real-tragedy

- Lackner and El-Iryani, “Yemen Environment Risk for Future,” pp. 2-5.

- “Pathways for Reconciliation in Yemen,” European Institute of Peace, 2022, https://www.eip.org/pathwaysforreconciliation

- Interview with a senior humanitarian aid worker in Yemen, March 20, 2023.

- Maia Baldauf, “Reframing Famine: New Approaches and Food System Accountability in Yemen,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 16, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/15312.

- “United Nations Yemen Common Country Analysis November 2021,” United Nations Yemen, January 25 2022, https://yemen.un.org/en/169479-united-nations-yemen-common-country-analysis-november-2021

- The list includes: absolute water scarcity and escalating rural conflict, rapid population growth, qat production, heatwaves, precipitation variability (resulting in droughts, floods, and pest outbreaks), land degradation, and groundwater reserve depletion.

- “Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework 2022-2024,” United Nations Yemen, October 26, 2022, https://yemen.un.org/en/204734-united-nations-yemen-sustainable-development-cooperation-framework-2022-–-2024 “Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework 2022-2024,” United Nations Yemen, October 26, 2022, https://yemen.un.org/en/204734-united-nations-yemen-sustainable-development-cooperation-framework-2022-–-2024

- “Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan 2023,” OCHA, January 25, 2023, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-humanitarian-response-plan-2023-january-2023-enar

- “Internal FAQ on environmental and social safeguards and risk screening,” World Food Programme, November 24, 2020, https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000143342/download/

- Interview with a senior humanitarian aid worker in Yemen, March 20, 2023.

- Ibid.

- “Yemen Country Engagement Note (CEN) FY22-23,” World Bank Group, April 28, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/yemen/brief/yemen-country-engagement-note-cen-fy22-23

- Interview with a development project officer in Yemen, May 14, 2023.

- “Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Yemen Food Security Response and Resilience Project,” World Bank Group, February 2, 2023, https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099214002022325529/p17612908838da050aef8042e792dc95e1

- Interview with a development project officer in Yemen, May 14, 2023.

- Enhancing Rural Resilience in Yemen is the first project phase title; now in its third phase, the project is titled Supporting Resilient Livelihoods, Food Security, and Climate Adaptation in Yemen (ERRY III).

- “Supporting Resilient Livelihoods, Food Security, and Climate Adaptation in Yemen, Joint Programme (ERRY III) Project Summary,” UNDP, https://www.undp.org/yemen/projects/supporting-resilient-livelihoods-food-security-and-climate-adaptation-yemen-joint-programme-erry-iii

- The ERRY II final evaluation report noted that no environmental risk assessments were conducted. Assessments for ERRY III were not available on relevant UNDP webpages.

- Interview with a senior development official in Yemen, March 23, 2023.

- Rodrigo Mena and Dorothea Hilhorst, “The transition from development and disaster risk reduction to humanitarian relief: the case of Yemen during high-intensity conflict,” Disasters, November 25, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12521

- Interview with a senior development official in Yemen, March 23, 2023.

- Focus group discussion with Yemeni experts, April 5, 2023.

- Ibid.

- Interview with a development project officer in Yemen, May 14, 2023.

- Interview with a senior humanitarian aid worker in Yemen, March 20, 2023.

- Focus group discussion with Yemeni experts, April 5, 2023; interview with a development project officer in Yemen, May 14, 2023.

- Interview with a senior humanitarian aid worker in Yemen, March 20, 2023.

- Focus group discussion with Yemeni experts, April 5, 2023.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The survey included 142 respondents residing in Abyan, Aden, Al-Bayda, Al-Dhalea, Al-Mahra, Amanat al-Asimah (Sana’a City), Dhamar, Hadramawt, Hudaydah, Lahj, Marib, Sana’a, Shabwa, and Taiz. See Appendix 1 for more on respondents’ profiles.

- Respondents were given the option to select multiple answers

- Respondents were given the option to select multiple answers.

- OCHA (2012) Humanitarian Response Plan for Yemen 2013, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/humanitarian-response-plan-yemen-2013

- Analysis drawn from: Lackner and Al-Eryani, 2020; Thomas, 2022; Huntjens et al., 2014; Basha, 2022, Wiebelt et al., 2011; Arabian Brain Trust, “An innovative Yemeni approach: Towards democratizing the drivers of development,” March 15, 2022, https://arabiabraintrust.co.uk/how-to-be-ahead-of-stock-changes/

- Maia Baldauf, “Reframing Famine: New Approaches and Food System Accountability in Yemen,” The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 16, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/15312.

- Peter Salisbury, “Brokering a Ceasefire in Yemen’s Economic Conflict.” International Crisis Group, January 20, 2022, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/yemen/brokering-ceasefire-yemens-economic

- Hadil al-Mowafak, “Yemen’s Forgotten Environmental Crisis Can Further Complicate Peacebuilding Efforts,” Yemen Policy Center, December 2021, https://www.yemenpolicy.org/yemens-forgotten-environmental-crisis-can-further-complicate-peacebuilding-efforts/

- “Pathways for Reconciliation in Yemen,” European Institute of Peace, 2022, https://www.eip.org/pathwaysforreconciliation

- Khaled Sulaiman, “Local Communities and Climate Challenges,” Arab Reform Initiative, September 23, 2021, https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/environmental-politics-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa-proceedings-from-first-inaugural-conference/