The Sana’a Center Editorial

Absent Reform, Yemenis Bear Brunt of Government Tariff Hike

The internationally recognized Yemeni government’s recent decision to dramatically increase customs tariffs on non-essential goods appears to be spurring price surges for imports across the board. Given that the primary driver of the country’s dire food security crisis is price volatility, and that the government’s recent tariff hikes threaten to exacerbate this humanitarian crisis, the government should reverse its decision immediately.

Under normal circumstances, it would be a sensible policy option for the Yemeni government to try to raise revenues through gradually charging importers more to bring foreign products into the country, especially non-essential goods. Yemen, notably, has some of the lowest customs tariffs in the Arab world, even while the government is facing a massive budget deficit with few other options available to narrow the gap between income and expenses. These, however, are not normal times.

Frontlines divide the country, and even at main seaports and border crossings in areas the Yemeni government supposedly controls, it has little to no presence on the ground. This severely hampers its ability to enforce customs procedures at all. Indeed, the Sana’a Center Economic Unit estimates that the state treasury currently receives less than 40 percent of the customs revenues it is legally due. The government’s ability to regulate the commodity and currency markets to protect consumers is also minimal, while major private sector actors and regional authorities have little confidence in the government’s administrative competence or capacity to act in a principled manner.

It is in this context that the Yemeni government announced on July 25 – with neither an implementation plan nor coordination with the private sector – that it was doubling the customs exchange rate on non-essential items. This means that for every US dollar an importer owes in customs duties, the amount owed will be 500 Yemeni rials (YR) instead of the previous YR250.

Business groups and representatives from across the country swiftly condemned the move, warning that it would disrupt the movement of goods, cause general price spikes, and further undermine food security in a country that depends on imports for up to 90 percent of the food items it consumes. Many traders with goods already unloaded at Aden port initially refused to pay the new customs fee and left their products waiting in warehouses. The Houthi authorities in the north condemned the move as well and sought to entice importers to divert their shipments through ports in Hudaydah governorate under Houthi control, where the previous customs exchange rate continues to prevail. The already byzantine processes importers and shippers must navigate to bring commodities into Yemen was thrown into further chaos, with traders seeking to circumnavigate the new tariff through redirecting incoming goods to different ports of entry.

The Yemeni government had claimed that the increased tariff would have a limited impact, not more than 5 percent, on the market prices of non-essential goods. Such may have been the case if the government had the capacity to regulate the commodity market and restrain traders’ self-serving tendency to preemptively pass on to consumers anticipated increases in the cost of doing business. Instead, as of this writing, the Sana’a Center had received reports from Aden and Hadramawt governorates that many products, both basic goods and non-essential items, had jumped in price through August. More data is needed to gauge the full impact of the Yemeni government’s tariff hike, but preliminary evidence suggests that Yemeni consumers are bearing the brunt of the fallout as importers pad their profit margins.

The government’s need to increase revenues is clear – it is currently covering its budget deficit, largely public sector salaries, through printing new currency, which is a primary reason for the rial’s rapid depreciation in non-Houthi areas. This in turn undermines local purchasing power and deepens the humanitarian crisis. The government, however, implemented its new policy without being in a position to substantially gain from it, given its severely limited ability to enforce revenue collection. (It is important to note here that the Houthi authorities’ greater success at reining in their budget deficit has been accomplished by coercive and extensive taxation measures and collection, denying almost all public sector workers in areas they control a salary, and instead directing most of their revenues – including a 30 percent tariff on goods entering the north from government-held areas – to their war efforts).

Prior to the conflict, Yemen’s customs administration was one of the country’s most corrupt government agencies. During the ongoing conflict, the capacities of the customs administration – and the Yemeni government’s revenue mobilization capacity in general – substantially deteriorated and created a conducive environment for a significant revenue leakage. Administrative reforms are needed to fix these holes, and to shield consumers from importers’ price gouging, before any new fees are introduced. Without such reforms, smuggling and corruption related to imports will be further incentivized, consumers will continue to suffer price shocks, and the Yemeni government’s budget deficit will see little reprieve in return.

Contents

New Fronts in the Economic War

- CBY-Aden Orders Banks to Move Headquarters South

- Yemeni Banks and CBY-Sana’a Seek to Resist CBY-Aden Measures

- Yemeni Government Receives US$665 million Worth of IMF Support

- CBY-Sana’a Opposes CBY-Aden’s Control of IMF Support

- Political and Economic Developments Heighten Currency Instability in Non-Houthi Areas

- Official Fuel Prices Increase in Southern and Eastern Governorates

- Developments in Government-Controlled Territory

- Developments in Houthi-Controlled Territory

- International Developments

- Fighting Focused Around Marib, Shabwa and Al-Bayda

- Houthis Open New Front in Marib, Though Stalemate Continues

- Tribes Negotiate Exit of Houthi Forces From Villages in Al-Bayda

- Houthi Missiles Again Strike Al-Anad Base in Lahj, Killing Dozens

- Islah-Affiliated Forces Provoke Violent Civil Unrest in Taiz

- What Yemenis Can Learn From Afghanistan

- The STC’s Delicate Balancing of Contradictions

- Friends with Enemies: Hamas’ Attempts to Navigate Between Islah and the Houthis

August at a Glance

New Fronts in the Economic War

By the Sana’a Center Economic Unit

CBY-Aden Orders Banks to Move Headquarters South

The battle between the fragmented Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) branches over control of Yemeni banks’ operations and financial centers escalated dramatically in August, further threatening their ability to operate in Yemen. On August 5, CBY-Aden ordered Yemeni commercial and Islamic banks to, among other things, relocate their headquarters to fully operate from Aden. CBY-Aden’s August 5 statement reminded Yemeni banks to submit the financial data it had previously asked for within 15 days of July 6. The statement also threatened punitive measures against non-compliant banks. These include an implied threat to companies and commercial institutions carrying out financial or banking operations through non-compliant banks, such as opening letters of credit (LoCs) and making financial transfers. The statement warned that CBY-Aden could not be held responsible for any catastrophic consequences for involvement in financial transactions with non-compliant banks.

The statement went on to say that a list of those banks not in compliance with the instruction to move to Aden would be announced and made available to all local bodies, banks, external financial and banking institutions, and relevant international organizations.

Finally, CBY-Aden also said in its statement that for those Yemeni banks that did comply with its instructions, it would transfer foreign exchange reserves to those banks’ correspondent accounts, enabling them to finance imports.

The move comes as the latest salvo in the long economic war between rival branches of the fragmented CBY. CBY-Aden and CBY-Sana’a started to escalate competition for control over access to data held by Yemeni banks and money exchange firms toward the end of 2020. This, in turn, led to punitive measures against the banks, including the imposition of large fines and three banks being taken to court in Aden for non-compliance. Meanwhile, two banks were closed by the Houthi movement-run Security and Intelligence Bureau (SIB) in retaliation for sharing data with CBY-Aden.

The CBY-Aden’s August edict will pose a major challenge for the country’s banks. Seventeen out of 18 Yemeni banks have their headquarters in Sana’a, while nearly all Yemen’s commercial and Islamic banks have concentrated their business activities and built strong commercial ties in the northern part of the country, with these arrangements now difficult to compromise.

According to a senior banking official who spoke with the Sana’a Center Economic Unit on condition of anonymity, a possible solution now under consideration is to allow Yemeni banks to open a second headquarters in Aden in addition to maintaining their current headquarters in Sana’a. Yet, while such a solution might be superficially implemented, doubts remain high as to whether CBY-Sana’a will agree to this arrangement and allow CBY-Aden to access banking data through newly-envisioned headquarters, which would operate in parallel from Aden and implement monetary policies in areas controlled by the Houthi authorities.

Instead, CBY-Sana’a would likely continue to prevent Yemeni banks from sharing their data with CBY-Aden, while insisting on the Houthi movement’s strategic solution to the existing financial sector crisis: a de facto division of monetary authority and capacity between Houthi- and internationally recognized government-held areas.

Given CBY-Aden’s weak institutional capacity and the unstable political environment in which it operates, it needs to be cautious over how to proceed with its order to relocate banking sector headquarters to Aden. This instruction could threaten a wide variety of financial activities and have fundamentally destabilizing humanitarian and economic fallout. Without a solution to de-escalate the standoff between the two fragmented CBY branches, the financial sector in general and the banking system in particular will become highly fractured, with its capacity to provide financial services significantly impaired. The country is likely to experience further distortion of the monetary cycle, with a dual financial system arising at the banking level, increased black market economic activities and an accelerated devaluation of the rial.

Yemeni Banks and CBY-Sana’a Respond to CBY-Aden Measures

On August 9, CBY-Sana’a released a statement condemning CBY-Aden’s recent escalation, saying that it would harm the national banking sector and asking for banking and economic activities to be kept away from political competition.

CBY-Sana’a also said it had never objected to banks providing CBY-Aden with data and reports related to clients and the transactions of branches operating in areas outside of Houthi control. CBY-Sana’a did, however, say that transferring the CBY headquarters to Aden was a violation of the Yemeni constitution that politicized the bank and enabled it to be used for financing the war. Given these factors, CBY-Sana’a said, it would be justified in directing banks not to share client and operational data with CBY-Aden.

Then on August 12, the Yemen Banks Association (YBA), based in Houthi-controlled Sana’a, released a statement condemning CBY-Aden’s threatened punitive measures against Yemeni commercial and Islamic banks that refuse to share data or relocate their headquarters to Aden.

The statement said that CBY-Aden’s recent escalation went against the central bank’s legal role as a monetary authority responsible for providing a safe means for banks to operate in the country while protecting bank depositors’ money.

The YBA claimed that CBY-Aden’s recent move was in violation of Yemeni banks’ internal regulations and the country’s existing legal framework regulating the banking sector. YBA stated that Yemeni banks – just like other banks around the world – chose a location for their headquarters near to the country’s main commercial and industrial centers, with most of these located in Sana’a. This is where banks have lent the bulk of their financial resources, with banks headquartered there in order to help them follow up with developments and issues related to those investments.

The YBA also stated that in accordance with Central Bank Law No. 14 of 2000, one of the central bank’s main responsibilities is to preserve depositors’ money. Transferring Yemeni banks’ headquarters to Aden might, however, expose depositors’ assets to several risks. These include a potential decrease in value, due to the differential between the exchange rate of the Yemeni rial in Aden compared to that in Sana’a.

In addition, the YBA said that CBY-Sana’a was exercising actual supervision, ensuring that the banks continued to apply banking laws and regulations, including global procedures and standards for combating money laundering and terrorist financing. This statement could imply, too, that the YBA does not judge the CBY-Aden as sufficiently qualified to perform a banking supervision role.

The YBA then appealed to local and international actors to use their relationship with authorities supervising CBY-Aden to pressure them to respect the independence and impartiality of the Yemeni banking sector, and allow it to perform its functions away from political polarization. The YBA statement concluded that the Yemeni banks retained their legal right to respond to CBY-Aden’s moves, including the right to call for a partial or comprehensive strike in the Yemeni banking sector.

Notably, in approving each commercial and Islamic bank’s applications for the necessary licences to operate in the first place prior to the current conflict, the Yemeni central bank approved the banks’ internal regulations and structures, which included the location of each bank’s headquarters. A Sana’a Center Economic Unit review of the relevant legislation – Chapter 7 of the Central Bank’s Law No.14 of 2000 regarding the CBY’s relationship with banks and financial institutions, Law No.38 of 1998 regarding banks and Law No.21 of 1996 amended by Law No.16 of 2009 regarding Islamic banks – there are no legal provisions that give the CBY-Aden the authority to withdraw its previous approval. Given such, it would appear the CBY-Aden’s demand that Yemeni banks relocate their headquarters has no legal basis. This is in addition to the fact that the Yemeni government-affiliated central bank is attempting to mandate that the country’s banks move their headquarters to a location where the CBY-Aden itself has been unable to perform basic monetary functions.

Yemeni Government Receives US$665 million Worth of IMF Support

On August 23, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) allocated a total of US$665 million worth of foreign currency reserves to Yemen in the form of Special Drawing Rights (SDR), the IMF’s supplementary foreign exchange reserve assets. SDRs are valued relative to a basket of key international currencies – the Chinese yuan; the Euro, the Japanese yen, the British pound, and the US dollar– and while not a currency themselves, SDRs can be exchanged with IMF member countries for hard currency.

The reserves allocated to Yemen are part of the IMF’s largest ever single allocation of SDR, SDR456 billion (US$650 billion), approved on August 2 to address the global need for foreign currency reserves and help countries deal with the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The SDR allocated to Yemen is set to be channeled through the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the central bank in Aden (CBY-Aden). While the IMF allocates SDRs unconditionally, countries potentially willing to carry out the SDR conversion may present Yemen with conditions. Indeed, according to one Yemeni economist who spoke to the Sana’a Center, it is highly likely that the internationally recognized Yemeni government and CBY-Aden would need to provide countries that might consider exchanging the SDR with a detailed plan on how the physical foreign currency reserves would be used. CBY-Aden continues to suffer ongoing capacity issues and confidence concerns among both domestic and external actors. Therefore, long-requested structural reforms at the bank might need to be carried out for a conversion to take place. Many stakeholders and observers, including the Sana’a Center, have called for the CBY-Aden board of directors to be replaced, owing to concerns over how the board managed the now-exhausted US$2 billion Saudi deposit that was intended to finance the import of essential commodities. Concerns also include the central bank’s broader management of monetary policy.

The initial expectation is that CBY-Aden will seek to use the SDR allocated from the IMF to underwrite the import of essential commodities (e.g. food and medicine), in addition to covering some government expenditure. In turn, this would at least help the government and CBY-Aden mitigate some of the exchange rate volatility in non-Houthi controlled areas, if not help to actually improve the market exchange rate.

CBY-Sana’a Opposes CBY-Aden’s Control of IMF Support

On August 29, the central bank in Sana’a (CBY-Sana’a) released a statement expressing its opposition to the fact that the IMF will entrust CBY-Aden with the management of Yemen’s allotted SDR units.

CBY-Sana’a outlined previous correspondence with the IMF and other international actors on this issue, referencing an earlier letter addressed to the IMF on June 3. In this, CBY-Sana’a questioned the legality and legitimacy of CBY- Aden, and highlighted widespread accusations of corruption and mismanagement that hang over the latter, specifically in regard to the management of the above-mentioned Saudi deposit.

CBY-Sana’a also viewed the IMF’s position on the SDR allocation as a departure from previous assurances of neutrality, and listed three demands. These were: a freezing of the allocation of SDR units and the prohibition of CBY-Aden from using them; the choosing of a third-party to manage the SDR units that would be used to underwrite imports and pay public sector employee salaries for six consecutive months; and the covering of debt owed to Yemeni banks. The third demand relates to the money the banks have tied up in public debt instruments (e.g, treasury bills) that CBY-Sana’a has frozen and stopped paying interest on.

In its August 29 statement, CBY-Sana’a warned the IMF that it will not accept any responsibility for the fallout from the IMF’s current stance on the SDR allocation. This can be interpreted as a preemptive warning of further escalation from the Houthi movement and CBY-Sana’a amid ongoing economic competition with the internationally recognized government and CBY-Aden.

CBY-Sana’a concluded its statement by stating that if its demands were not met, it would cut off all forms of cooperation and communication with the IMF, in addition to signaling to the new UN special envoy, Hans Grundberg, that it will treat his handling of the IMF SDR allocation as an early litmus test of his professionalism and impartiality.

In a separate correspondence, the Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Houthi-run National Salvation Government (NSG), Hisham Sharaf Abdullah, addressed a letter on August 30 to IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva. Compared to the CBY-Sana’a statement, the letter was softer in tone, despite emphasizing the opposition of the NSG to the IMF’s decision to allocate SDR units to CBY-Aden. In the letter, Abdullah calls on the IMF to assume responsibility for the close monitoring of how the SDR units are spent, warning of potential misuse and corruption.

Political and Economic Developments Heighten Currency Instability in Non-Houthi Areas

During the month of August, the value of the Yemeni rial (YR) in areas outside of Houthi control temporarily improved, from YR1,060/US$1 on August 9 to YR950/US$1 on August 11. The improvement was short-lived, however, with the rial subsequently depreciating to YR1,042.50/US$1 on August 22. By the end of August, the exchange rate had picked up again slightly, to stand at YR1,028/US$1.

The temporary improvement in the value of the Yemeni rial in the first half of the month came alongside reports that the positions of governor, deputy governor, and board of directors for CBY-Aden were under review and subject to change. These changes are viewed by some as necessary, in order to unlock any potential additional financial support that might otherwise be provided to the internationally recognized Yemeni government and CBY-Aden from Saudi Arabia.

On August 16, President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi held a meeting in Riyadh with Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed, the governor and deputy governor of CBY-Aden, Ahmed al-Fadhli and Shakeeb Hobish, as well as members of the bank’s board of directors. Reports on the meeting read as though Hadi provided CBY-Aden with a vote of confidence, despite the accusations of mismanagement. The value of the Yemeni rial depreciated in the days that followed the Riyadh meeting.

As confidence in CBY-Aden remains low among domestic and international actors, the Southern Transitional Council (STC) is meanwhile trying to exert its authority over the management of the local currency and the local economy in Aden, and southern Yemen more broadly.

The STC has publicly held the internationally recognized Yemeni government responsible for the depreciation of the Yemeni rial in areas outside of Houthi control. In an attempt to assert itself, in mid-August, senior STC officials organized a meeting with Aden-based money exchangers. At this, the officials outlined plans to coordinate with the exchangers to reduce the exchange rate against the Saudi riyal (SAR) by YR5 per day to reach a target of YR240/SAR1. This particular proposal was followed by a circular produced on August 17, which aimed to fix the buying and selling of Saudi riyals at YR247 and YR249/SR1, respectively, for a one-week period.

Local sources in Aden that the Sana’a Center spoke with, however, dismissed the impact of the STC action on local currency and exchange dynamics. This dismissal came amid reports of currency speculation and a notable gap between the buying and selling rates of Saudi riyals, as applied by local money exchange companies. This spread was widely deemed to be excessive and an example of blatant profiteering. Irrespective of its impact thus far, the STC appears to be trying to fill a space left by CBY-Aden, as the bank continues to operate at reduced capacity, with decreased confidence in its monetary policy, and looming question marks over its future.

In addition to the pressure that the STC is applying, CBY-Aden also faced a new round of escalation in its ongoing battle with CBY-Sana’a over the regulation of money exchange companies.

In Early August, CBY-Aden issued a list of over a dozen money exchange companies that are prohibited from providing transfer and remittance services in areas outside of Houthi control. On August 10, CBY-Sana’a responded with its own separate list, which included 14 money exchange companies that are no longer authorized to operate in Houthi-controlled areas. Based on the names of the money exchange companies included on the two separate lists, it would appear that the dynamics of the political economy are now influencing the regulation of money exchange companies.

Official Fuel Prices Increase in Southern and Eastern Governorates

On August 17, the Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) branch in Aden announced that it was increasing the price of petrol from YR11,200/20 liters to YR12,000/20 liters.

The increase in the ‘official’ price of petrol sold at YPC-run stations in Aden and by agents of YPC occurred in response to the depreciation of the Yemeni rial. Similar price increases have also occurred in Mukalla, Shabwa, and Al-Dhalea governorates and are all linked to the weakening of the local currency.

The Political Arena

By Casey Coombs

Developments in Government-Controlled Territory

Riyadh Mediates Yemeni Government-UAE Standoff at Balhaf LNG Terminal

Tension rose in August around the Balhaf liquified natural gas (LNG) export terminal in Shabwa governorate. The $4.5 billion LNG plant, the country’s largest investment project, sits along the coast of the Arabian Sea and, prior to the current conflict, liquified natural gas piped from Marib. Operations were suspended as the war escalated and for nearly five years the plant has served as a base for Emirati soldiers and the local Shabwani Elite forces they armed and trained

On August 1, Shabwa’s local authority, led by Shabwa Governor Mohammed Saleh bin Adio, voted unanimously to push for the immediate reopening of the facility. During the meeting at which the vote took place, Bin Adio argued that exports from the LNG plant would help prevent the collapse of the Yemeni rial and said that French Total, the multinational oil firm operating the facility, was eager to resume operations.

On August 24, security forces aligned with the internationally recognized Yemeni government established a checkpoint on the coastal road about 10 kilometers west of the Balhaf facility and arrested six members of the Shabwani Elite forces who were returning to the base, according to a source with the Shabwani Elite who spoke with the Sana’a Center. Later the same day four fishermen sailing near Balhaf were arrested by the Shabwani Elite forces, according to a member of the Fishermen’s Association. On August 27, a second government checkpoint was established on the coastal road about 1 km east of the Balhaf facility.

On August 30, Saudi forces arrived in Shabwa to mediate the situation at Balhaf, meeting with Bin Adio. The governor has been a vocal critic of the United Arab Emirates’ presence in Shabwa and has demanded that Emirati forces vacate Balhaf so export operations can be restarted at the LNG facility. The Saudi mediation team reportedly proposed two to three months for Emirati forces to evacuate Balhaf, but Bin Adio insisted the UAE forces evacuate immediately. An agreement on their date of departure had yet to be reached as of this writing. However, following the meeting, government forces removed the two checkpoints near the LNG plant and released the Shabwani Elite forces they had arrested in the previous week.

Police Chief in Wadi Hadramawt Survives Assassination Attempt

On August 12, the head of the Al-Najdah, or road security, forces in Wadi Hadramawt, Obaid Bazhir, was shot in the chest by a gunman in the northern city of Shibam. Bazhir’s bodyguards killed the gunman and transferred the police chief to a nearby hospital where his condition was stabilized. The governor of Hadramawt, Faraj al-Bahsani, called Bazhir to check on his health after what the governor’s office described as clashes with “terrorist elements.” Wadi Hadramawt has witnessed numerous assassinations of military and security officials throughout the war.

STC Tightens Security in Aden After Bomb Targets Security Forces

On August 15, Southern Transitional Council (STC) authorities in Aden tightened security a day after a massive explosion targeted newly recruited security forces in the northern parts of the city, killing two soldiers. A local government source told Xinhua that the authorities had deployed security units in Aden “and intensified their intelligence operations to thwart imminent terrorist attacks against state institutions in the city.”

Saudi Arabia Lays Off Scores of Yemeni Professionals

Hundreds of Yemeni medical professionals and academics in the kingdom’s southern region bordering Yemen were notified in late July and early August that their work contracts would not be renewed. A Saudi analyst told Reuters the layoffs were driven by security considerations in areas near the border with Yemen, and to create job openings for Saudi citizens.

Saudi Arabia hosts more than 2 million Yemeni workers who send billions of dollars worth of remittances home to their families each year, providing a lifeline to millions of people in Yemen’s war-ravaged economy and a key source of foreign currency for the country.

On August 21, the deputy minister of expatriate affairs in the internationally recognized Yemeni government, Mohammed al-Adil, announced on Twitter the “return of Yemeni faculty members at universities in southern Saudi Arabia to their work.”

The International Union of Yemeni Diaspora Communities said Al-Adil’s announcement that some academics in some southern Saudi cities could return did not go far enough, and that the exception of a few academics was an unsatisfactory effort to pacify anger toward the kingdom’s arbitrary layoffs.

House Speaker Says Parliament Will Convene in Sayoun

Yemeni Parliament Speaker Sultan al-Barakani told Asharq Al-Awsat that preparations were underway to hold parliament sessions “within weeks” in the city of Sayoun in Hadramawt governorate. The Yemeni parliament has only convened once during the war, in April 2019 in Sayoun. The city, which remains under the control of the internationally recognized Yemeni government, was chosen then as the venue instead of Aden to avoid direct confrontation with the STC. In late July, during Al-Barakani’s visit to Sayoun, the UAE-backed secessionist group vowed to disrupt any attempt to hold parliamentary meetings.

Military Court Sentences Houthi Leaders, Iranian Ambassador to Death

On August 25, the internationally recognized Yemeni government’s military court issued death sentences to Houthi leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi and 172 other leaders of the group as well as Iran’s ambassador to Yemen, Hasan Irlu, a former Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps commander who resides in Sana’a. They were sentenced to death by firing squad for their roles in the military coup against the republic starting in September 2014, spying for Iran and committing various war crimes. The military court also designated the armed Houthi movement a terrorist organization and ordered the confiscation of its property and transfer of its weapons and equipment to the Ministry of Defense. In 2017, a Houthi-run criminal court sentenced President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi and six other top officials in the internationally recognized government to death for “high treason.”

Developments in Houthi-Controlled Territory

Houthis Detain Journalist

On August 17, two weeks after Yemeni journalist Younis Abdulsalam disappeared off the streets of Sana’a, a lawyer representing his family said the missing reporter was being held by Houthi intelligence services. Abdulmajid Sabra, a Sana’a-based lawyer who has represented dozens of Yemeni journalists abducted by Houthis during the war, said Abdulsalam had suffered from depression since being detained by Security Belt forces in Aden last year and that his condition would likely worsen in Houthi custody.

Court Hearing Held for Imprisoned Model

On August 22, a Houthi court in Sana’a held the seventh hearing for Yemeni actor and model Entissar al-Hammadi, who was arrested by Houthi authorities on February 20. Al-Hammadi was unable to attend the hearing “due to riots in the women’s section of Sana’a Central Prison,” Yemen Future news outlet reported. Houthi authorities have restricted media coverage of the case following public pressure to release the young woman, sources told Yemen Future.

Documents Outline Jail Sentence, Fines for Artists Performing at Weddings

In mid-August, a document signed by Houthi authorities in Zaydiyah district in Hudaydah governorate surfaced online authorizing fines of 500,000 Yemeni rials and 20 days in jail for allowing singers to perform at wedding ceremonies. The document also prohibited “abnormal” haircuts among young people. The prohibitions, which reflect similar bans in Mahwit, Sana’a and Amran governorates since June, were justified by Houthi authorities as attempts to preserve religious identity.

International Developments

Iran’s New President, Houthis Quickly Establishing Ties

On August 4, Houthi news outlet Al-Masirah TV announced that the new Iranian president, Ibrahim Raisi, received the group’s delegation headed by spokesperson Mohammed Abdelsalam, in his “first official meeting” with an external delegation. The Houthi delegation traveled to Tehran as representatives of the president of the Supreme Political Council, Mahdi al-Mashat, to participate in the swearing-in ceremony for the hard-line Iranian president.

Then on August 25, Houthi Minister of Foreign Affairs Hisham Sharaf Abdullah congratulated Hussein Amir Abdollahian for his confirmation as foreign minister in the cabinet of President Raisi. In a cable, Abdullah called for strengthened communication and cooperation between the two governments and invited his Iranian counterpart to visit Yemen.

New British Ambassador to Yemen Starts Work

On August 5, Britain’s new ambassador to Yemen, Richard Oppenheim, said on Twitter that he had presented his credentials to the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates Affairs, Dr. Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak. It was Oppenheim’s first tweet since January, when he announced his appointment to replace the outgoing ambassador, Michael Aron. Prior to his appointment as ambassador to Yemen, Oppenheim was deputy head of the UK’s mission in Riyadh for three years.

Doha Resumes Diplomatic Ties with Riyadh

On August 11, Qatar named an ambassador to Saudi Arabia, four years after the two countries severed political, trade and travel ties. The new Qatari ambassador to Riyadh, Bandar Mohammed al-Attiyah, previously served as Doha’s ambassador to Kuwait and had mediated in the Gulf conflict. The dispute, which started in mid-2017, pitted Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Bahrain against Qatar over accusations that Doha was supporting Islamist groups the other states deemed terrorists.

Riyadh named an ambassador to Doha in June. The UAE, which has played a leading role in the Saudi-led coalition’s military intervention in Yemen, has restored trade and travel links with Doha but has yet to resume diplomatic relations.

AQAP Congratulates Taliban Takeover of Afghanistan

On August 18, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula congratulated the Taliban on its “conquest” of Afghanistan. In a two-page statement, AQAP said the victory proved that jihad, rather than democracy and other peaceful means, was the way to achieve political goals.

Casey Coombs is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies and an independent journalist focused on Yemen. He tweets @Macoombs

State of the War

By Abubakr al-Shamahi

Fighting Focused Around Marib, Shabwa and Al-Bayda

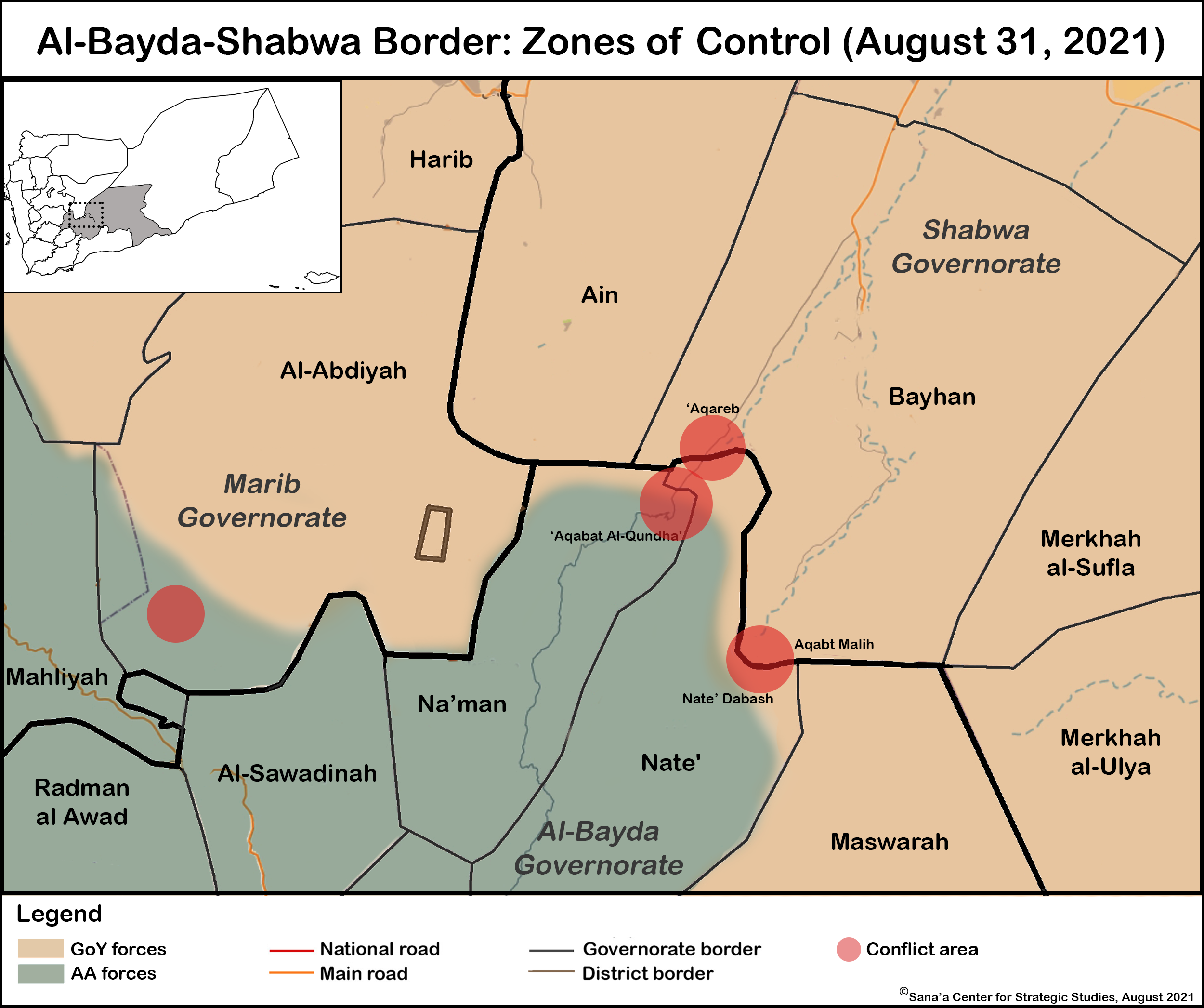

The contiguous governorates of Marib, Al-Bayda and Shabwa were the main arena for fighting between Yemeni government and Houthi forces in August, although few advances were made by either side. An uptick in fighting in Shabwa is a cause for concern for the Yemeni government, with the governorate one of the few stable strongholds still in its hands. The clashes were focused in much the same areas as in July when fighting spilled over from Al-Bayda – the rugged border regions between the two governorates, and in western Bayhan district in Shabwa.

Both sides have advantages, which appear to have canceled each other out for the moment. The territory the Houthis took in July in Al-Bayda’s mountainous Nate’ and Na’man districts have served as strategic vantage points for their forces, allowing the group to shell Yemeni government positions they overlook in Shabwa. However, Shabwah’s importance, and in particular the oil and gas fields in the governorate, mean that the Saudi-led coalition has moved to bolster government forces and push back the Houthis.

Any advance into Shabwa would provide a morale boosting victory for the Houthis, and would allow the group to threaten the governorate’s oil and gas fields, as well as provide an entry point into other southern governorates. Holding territory in Shabwa would also serve the Houthis well in any future ceasefire negotiations. Another goal of the Houthi attacks in Shabwa is to cut Yemeni government supply lines between Shabwa and Marib, where the Houthis are also on the offensive. Cutting supply lines in Shabwa would stop supplies from reaching government forces in and around Marib city, but also in the Al-Bayda districts of Al-Sawma’ah and Maswarah, which are supplied from Shabwa via the southern Marib district of Al-Abdiyah.

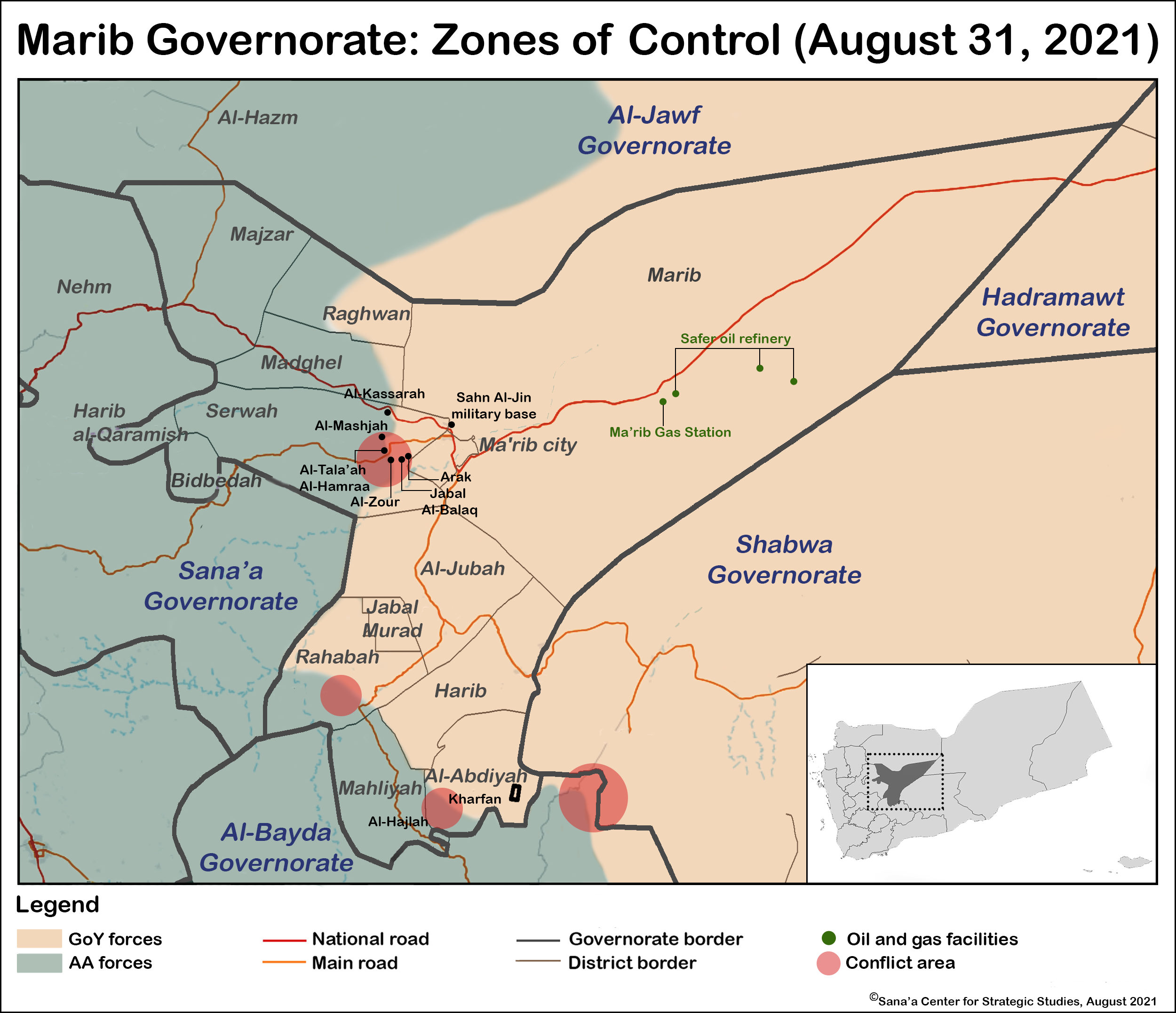

Houthis Open New Front in Marib, Though Stalemate Continues

Houthi forces also continued their attacks on government-allied tribal forces in Al-Abdiyah throughout August, while also pressing attacks along frontlines such as Al-Kassarah and Al-Mashjah, to the west of Marib city. Much as in previous months, no advances were secured there for either side, but the Houthis did open up a new front against government forces in mid-August in Arak, northern Wadi Dhanah, in Sirwah district, to the west of Marib city. Arak is heavily populated, and Houthi shelling of government forces there led to the displacement of civilians, according to locals and government security officials who spoke to the Sana’a Center.

Tribes Negotiate Exit of Houthi Forces From Villages in Al-Bayda

The intensity of the fighting in Al-Bayda governorate decreased relative to July, but continued in districts such as Al-Sawma’ah and Wald Rabee’ involving Houthi forces facing off against pro-government tribal forces. However, on August 5, the Dharibah tribe reached an agreement with the Houthis that stipulated the withdrawal of Houthis forces from the villages of Hilan, Zalqah and Raymah in Nate’ district, in return for a promise from the tribe that government forces would be prevented from being stationed in those areas, according to locals.

Houthi Missiles Again Strike Al-Anad Base in Lahj, Killing Dozens

Houthi long-range aerial attacks continued to pose a threat to government and Saudi-led coalition backed forces in other parts of Yemen far from the frontlines. On August 29, the Houthis succeeded in carrying out an attack on one of Yemen’s most important military bases, Al-Anad in Lahj, killing at least 40 soldiers, and injuring around 60. The use of ballistic missiles during the attack was confirmed by multiple sources, while soldiers at the base also reported hearing what sounded like a drone overhead the night before, indicating possible reconnaissance activity. Many of the soldiers killed were members of the 3rd Giants Brigade, composed mostly of Salafist and tribal fighters, predominantly from southern governorates, including the Al-Sobaiha tribes in Lahj.

The brigade, led by Abd Al-Rahman Al-Lahji, is seen as pro-government, and was forced to withdraw from the Red Sea Coast to Lahj after Al-Lahji’s refusal to report to pro-UAE figures such as Tareq Saleh. Al-Lahji’s rivals within the Saudi-led coalition backed Joint Forces had appointed a new commander for the 3rd Giants Brigade, who was on his way to Al-Anad before the attack took place.

The missiles were reportedly launched from the Al-Hawban area of eastern Taiz governorate, which is controlled by Houthi forces. In January 2019, a Houthi drone armed with explosives killed several military leaders taking part in a military parade at Al-Anad air base.

Islah-Affiliated Forces Provoke Violent Civil Unrest in Taiz

Government-held areas in Taiz continue to be rife with criminal activity and instability, often blamed on government forces. The 170th Air Defense Brigade, part of the pro-Islah Taiz Military Axis, has been at the center of several violent incidents in Taiz city throughout August. On August 10, seven people, including a child, died in clashes that began after a field commander in the brigade attempted to seize land in western Taiz city, according to local sources and media reports.

The field commander, Majed al-Araj, was killed in the fighting, which occurred after he opened fire on members of the Al-Hareq family, who owned the land at the center of the dispute. One of those killed was Issam al-Hareq, the deputy police chief in Bir Basha neighborhood. Al-Araj’s bodyguards proceeded to besiege the hospital where members of the Al-Hareq family were being treated, and stormed the Al-Hareq family home.

The announcement of an investigation into the events surrounding the clashes by Taiz security officials did little to quell the violence, and on August 18, clashes broke out once again, this time between government police officers protecting the Al-Hareq family home, and gunmen affiliated with Issa al-Ajooz, a pro-Islah member of the government’s General Security forces. One of Al-Ajooz’s gunmen was killed in the fighting, before Al-Ajooz fled, according to local media reports.

Meanwhile, on August 28, an armed group led by Abd Al-Wahed al-Qaisi, a soldier in the 170th Air Defense Brigade, kidnapped a judge, Ibrahim al-Majidi, in Taiz city, local sources told the Sana’a Center.

Abubakr al-Shamahi is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies

Commentaries

What Yemenis Can Learn From Afghanistan

Commentary by Maysaa Shuja al-Deen

In barely a week, the Taliban went from holding little territory in Afghanistan to controlling the state. The rapid collapse of the Afghan government captivated the world’s attention and resonated in particular with Yemenis, who witnessed a similar collapse in 2014 when the armed Houthi movement took control of Sana’a.

In Afghanistan, President Ashraf Ghani fled the country reportedly with suitcases full of cash, a claim he has denied. In Yemen, President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi was placed under house arrest and resigned the presidency under pressure before escaping Sana’a and calling on Yemen’s neighbors to intervene militarily.

As in Afghanistan, where Taliban militants broke into the homes of wealthy Afghan officials, so too do Yemenis remember Houthi fighters doing the same in 2014, breaking into the homes of prominent adversaries such as Hameed al-Ahmar and Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar. Both the Houthis and the Taliban claim that the governments they overthrew were corrupt. And both have a point.

Both Ghani’s Afghan government and Hadi’s Yemeni one were backed by outside powers – the US in the case of Afghanistan, and Saudi Arabia in the case of Yemen. Perhaps it shouldn’t be a surprise that both presidents are in exile, and that the militaries of both suffer from common phenomena like ghost soldiers and double-dippers.

The scenes from Afghanistan in the past month have raised a number of questions for Yemenis about the state of the war and the future of their country.

Broadly speaking, Yemenis fell into three camps as they watched the events in Afghanistan unfold. The Houthis – along with some leftist figures – see the Taliban victory as one of resistance triumphing over American occupation. This is in line with the Iranian “resistance” narrative, which tends to paint everything that is happening in the world as a struggle between the “west” and local resistance.

By contrast, many in the anti-Houthi coalition saw the Taliban takeover as the first step toward dragging Afghanistan back into a vicious civil war and the dark days of the Taliban’s draconian rule in the 1990s.

Others among the anti-Houthi side, however, take a kinder view of the Taliban, claiming that they’ve changed their ways in the 20 years since 9/11 and the US invasion. Many of those who hold such a position are supporters of the regional Muslim Brotherhood movement, whose main affiliate in Yemen is the Islah party, though this is not the official stance of the party itself. Like the Houthis, many Brotherhood supporters see the Taliban victory as an Afghan victory over the US. But unlike the Houthis, who tend to dissasociate themselves from the Taliban, the Muslim Brotherhood defends the group. This contradictory stance of the Brotherhood – both regionally and in Yemen – is particularly surprising. They reject the Houthi narrative about being a national movement confronting external aggression, and accuse the group of turning its back on the 2013-2014 National Dialogue Conference and seizing power by force, while commending the Taliban for this.

Each of these camps took a certain view of what was happening in Afghanistan, and each has taken a lessons-learned approach to the Taliban takeover.

The anti-Houthi coalition viewed the government collapse in Afghanistan as the direct result of an ill-considered US withdrawal and years of corruption in Ghani’s government. The result: a hardline religious militia took control of the country. The question many in this camp are now asking is: what would happen in Yemen if Saudi Arabia suddenly withdrew? Would the Houthis, like the Taliban, seize the rest of the country in a matter of weeks?

One could argue that the Taliban’s reconquering of Afghanistan owes more to the US intervening in the first place than the US withdrawing. For the past twenty years, the Taliban has largely cloaked its actions not as ideological or sectarian, but rather as patriotic resistance to foreign occupation. The same could be said for the Houthis, which have used the Saudi-led war in Yemen to their advantage, shouting down internal challenges to their rule by focusing on an outside power that is continually dropping bombs.

The lesson the pro-Houthi camp took from Afghanistan is that in the event of a complete Houthi victory over Yemen, thousands would flee the country, much as they did in Afghanistan. Like the Taliban, the Houthis represent a particular sect and ideology that attempts to impose its views on the rest of society. Could the Houthis survive such a “brain drain” in Yemen? Can the Taliban in Afghanistan?

What all these different groups in Yemen seem to realize after watching the recent news from Afghanistan is: what happened there could happen here. Foreign intervention cannot continue forever, particularly when it is hampered by weak and corrupt allies distanced from the community they claim to represent.

In the event of a Saudi military withdrawal, the Houthis could expand across Yemen, including in the south, even if some southerners are deluded into thinking there is an international red line when it comes to the south. If the coalition withdraws from Yemen, it will not return quickly.

Like in Afghanistan, in the absence of robust foreign air support for pro-government forces, the Houthi movement could quickly secure victory. But like the Taliban, the Houthis would then have to impose governance across an entire country. The jury is still out on Afghanistan, but it is doubtful whether the Houthis could succeed in carrying out such a political project in Yemen.

The Houthis control the Zaidi tribal areas in the north, where the group has a popular base of support. They also control some Shafi‘i areas such as Ibb and Hudaydah, both of which have a history of being amenable to central government control. The situation, however, is different in the Sunni tribal areas around Marib and Shabwa, or in complex urban areas such as Taiz and Aden, as well as in southern regions such as Al-Dhalea and Lahj, where communities are armed and outraged by any attempt by northerners to impose hegemony.

Any Houthi military expansion in these areas will only lead to more fighting. Young men will join armed groups, some of which may be religiously extremist or terrorist groups. Yemen will see the sort of regional rebellions comparable to Houthis’ battles against the Saleh regime between 2004 and 2010. Only this time, the Houthis won’t be the insurgents.

In many ways, Afghanistan is a warning to Yemenis on all sides of the current conflict. The anti-Houthi side will fret about their future should the Saudis withdraw. The pro-Houthi side will see a template for a quick and easy takeover of an entire country. But both should be aware that as bad as Yemen is at the moment, it can always get worse – for all the parties, for the people, for everyone.

Maysaa Shuja al-Deen is a non-resident fellow at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies where her research focuses on religious sectarianism, political transformation and Yemen’s geopolitical role in the region.

The STC’s Delicate Balancing of Contradictions

Commentary by Hussam Radman

Nearly two years ago, in November 2019, the Southern Transitional Council (STC) signed the Riyadh Agreement, the Saudi-brokered deal that laid out a power sharing arrangement between the group and the internationally recognized government led by President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi. Since then, the STC has attempted to be all things to all people, trying to balance four inherently contradictory roles: an official political entity that shares power with the internationally recognized government; an armed revolutionary movement seeking an independent southern state; a popular opposition leading street protests; and the de facto governing authority across parts of the south.

At different times in the past two years, the STC has attempted to fulfill one or more of these various roles. After signing the Riyadh Agreement, the STC was recognized as a political entity by Hadi’s government and Saudi Arabia. But that didn’t translate into greater political cohesion within the anti-Houthi alliance. Both Hadi’s government and the STC dragged their feet on implementing the agreement, bickering over roles and sequencing.

Frustrated and looking to create facts on the ground, the STC announced that it would impose self-rule on all southern governorates in early 2020. While it wasn’t able to take over every southern governorate, the STC did manage to take control of Aden, Lahj, Al-Dhalea and Socotra, along with parts of Abyan, where STC forces and troops loyal to Hadi engaged in fierce fighting. After a few months of consultations, the STC backtracked on its policy of escalation and agreed to re-engage with the Hadi government on implementing the Riyadh Agreement.

Months later, in November 2020, the STC officially joined Hadi’s government, accepting five of the 22 cabinet seats along with the governorship of Aden. But within months the STC was calling for protests outside the Ma’ashiq Palace, the seat of the government in the interim capital Aden, against that same government. Protestors stormed the residence of Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek, leading the cabinet to flee Aden.

In May 2021, STC leader Aiderous al-Zubaidi then called on the government to return to Aden in a television address. However, in the same speech, Al-Zubaidi portrayed the government’s influence in Sayoun, Shabwa and Al-Mahra as an “occupation”, calling on STC supporters to continue their protests against the local authorities there. Then, in June, Al-Zubaidi unilaterally announced a restructuring of his military and security forces, integrating them into the ministries of defence and the interior forces. He also established new forces in the name of combating terrorism.

This is what the past two years have been within the STC: escalation followed by conciliatory steps as the group attempts to gauge exactly what the international community will tolerate as well as how much support it has on the ground.

Part of the issue is that none of the options really gives the STC what it wants. Joining Hadi’s government as part of the Riyadh Agreement eased the pressure from Saudi Arabia, but within the government the STC has little power. Decision-making remains monopolized by President Hadi and his allies within Islah. As a result, the STC has reverted to pressuring Hadi from the position of an opposition. But, much like its role within government, the STC is strong enough to compel some changes but too weak to achieve its political goals.

Saudi mediation successfully defused tension in Shabwa and Abyan, but didn’t change the dynamics in the south. Both sides – the STC and Hadi – think they can win the long game, and so each has embarked upon a war of attrition with the other. All of this, of course, comes at the expense of revitalizing state institutions, fighting the Houthis, and mitigating the ongoing economic collapse. The STC and Hadi are too busy scheming against one another to present a unified front.

The STC’s multiple and contradictory roles have also undermined its ability to portray itself as a successful alternative ruling power and threatened to erode its base of support, particularly in Aden. The STC recently realized these risks and rushed to resolve them through more independent action, particularly in the economy and the judiciary.

Over the past two months, Al-Zubaidi has held extensive meetings with the Economic Committee of the STC and the Southern Exchangers Association in an attempt to curb currency speculation. In a similar context, the STC provided political cover for a syndicate group from the judicial authority called the ‘Southern Judges Club’, and in February 2021 directed its security units to respond to the Club’s calls to suspend the work of courts in the interim capital in protest against President Hadi’s decision to appoint a pro-Islah Attorney General. However, this escalation completely paralyzed public life in STC-controlled areas, and the Southern Judges Club was forced to end its strike in mid-August. In August, the STC supported the Southern Judges Club in establishing the Supreme Commission for the Administration of Judicial Affairs, a legal body with the mandate to oversee the judiciary in Aden. This is likely to further complicate the relationship between the official state agencies and the STC’s parallel institutions.

The STC is also attempting to strengthen local authorities in Aden, which report to Aden governor Ahmed Lamlas, an STC official, to fill the vacuum resulting from the government’s absence. A similar effort is being carried out on the military front, with the STC attempting to create independent channels of self-financing to deal with the fact that wages have been cut off by Saudi Arabia and the Yemeni government for almost a year.

The STC, however, has to be careful not to go too far. It doesn’t want to unduly anger Saudi Arabia, which continues to exert considerable influence over the group, and it doesn’t want to alienate the international community and the United Nations to the point that it can’t eventually be recognized as the representative of the South in any political negotiations.The STC wants to be seen as part of the solution to the Yemen problem. This means that it has to play nice with Hadi, remaining in his government and giving him some token support, but without conceding its main goal represented in establishing an independent south. So the STC will continue to do what it has been doing: take one step in this direction and then another in a seemingly contradictory direction. All with the goal of not alienating too much either its international audience or its domestic one.

The standard for the STC’s success in its current policy is linked to two major points: its ability to stand as a major actor in the formula of the Yemeni conflict – which was relatively achieved in the South despite the increasing military and political threats around it – and its ability to transform into a model of governance that attracts popular support in areas it controls, especially in the interim capital Aden. The STC faces real difficulties in that regard, as it is no longer possible to isolate its successes from the successes, or failures, of the Yemeni government, or to distance itself from the repercussions of the economic collapse the Yemeni state is witnessing.

Hussam Radman is a journalist and Sana’a Center research fellow who focuses on southern Yemeni politics and militant Islamist groups. He tweets at @hu_rdman.

Friends with Enemies: Hamas’ Attempts to Navigate Between Islah and the Houthis

Commentary by Tawfeek al-Ganad

At the end of May as Israeli military attacks on the Gaza Strip intensified, Mohammed al-Hazmi, an Islah official, sparred with Hussein al-Imad, a Houthi official, on Twitter. Al-Hazmi criticized the Houthis’ public donation of cash to Palestine, claiming the group were thieves who had stolen money and property from him and others in Sana’a. Al-Imad shot back that Jerusalem’s money had been returned to Jerusalem, implying that the money Al-Hazmi himself had previously raised for Palestine through his mosque had actually gone into his own pocket.

The dueling accusations between a Houthi official and an Islah official illustrated how Yemeni parties often use the plight of Palestinians for their own domestic purposes. Political groups of all stripes in Yemen seek to gain popularity by asserting their support for the Palestinian cause, which is near universally popular in Yemen. Historically, it is the one thing, more than any domestic issue, that Yemenis of all political persuasions could agree on.

Following the Palestinian Liberation Organization’s expulsion from Lebanon in 1982, then President Ali Abdullah Saleh allowed the creation of military camps for the group south of Sana’a. The various other Yemeni actors continued to compete to be seen as champions of the Palestinians in order to gain popular support. For instance, the Houthis have long made the destruction of Israel part of their official motto. The one notable exception is the Southern Transitional Council (STC), whose officials made remarks that appear to be in favor of the UAE’s recent normalization of ties with Israel.

However, like many outside actors, Hamas has had difficulty navigating its relations in Yemen during the current conflict, with the Palestinian group’s actions at various times being interpreted as picking sides, which has put its universal appeal in Yemen in jeopardy. Hamas was initially seen as supporting the internationally recognized Yemeni government, drawing Houthi ire, before more recently appearing to grow closer to the group, which has drawn rebuke from Islah, among others.

Since the 1970s, Palestinian teachers from the regional Muslim Brotherhood movement were brought to Yemen to teach in institutes that acted as a parallel education system run by the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1970s and Islah in the 1990s. There were Palestinian military experts and trainers who worked with the armies in both the North and South Yemen, and wealthy Palestinian businessmen operated companies in both in Sana’a and Aden. By the time Yemen unified in 1990, a Palestinian embassy had opened in Sana’a with separate offices for both Hamas and Fatah.

Hamas’ relationship with Sana’a was similar to that of any other sovereign state, communicating directly with the Yemeni government. Hamas also had the support of Islah and its leader, the influential Sheikh Abdullah al-Ahmar, who at the time was Yemen’s speaker of the parliament as well as the head sheikh of the Hashid tribal confederation. Al-Ahmar, like many prominent Yemenis, also headed an association to support the Palestinian cause.

After the outbreak of the Second Intifada in 2000 and the rise of Mahmoud Abbas, a Palestinian political figure Yemenis generally regarded as bland, Fatah’s popularity decreased dramatically in Yemen. When Israel imposed a blockade on Gaza in 2010, officials from Islah were among the hundreds of people aboard the six ships of the “Freedom Flotilla” that attempted to break the blockade. Among the most prominent Islah figures to participate was Mohammed al-Hazmi, a member of parliament for Islah at the time.

Over the years Hamas maintained a robust network with the thousands of Palestinians who lived in Yemen, distributing food baskets during Ramadan to Palestinian families and providing animals to sacrifice on Eid al-Adha. It also provided medical and livelihood support.

However, many Palestinians began leaving Yemen following the country’s 2011 uprising. At the beginning of the current Yemeni conflict Hamas attempted to support Palestinians in the country through distributing small cash payments to families. It was not long, though, before Hamas, like many other foreign actors, was caught between sides in Yemen’s war. Its relationship with Islah led to the Houthis closing Hamas’ office in Sana’a in 2014. Hamas’ representative in Sana’a left a few months later, in March 2015, when the Saudi-led coalition launched Operation Decisive Storm in Yemen.

Beyond Yemen, Hamas’ support for the Arab Spring uprisings, and its ties to Iran, helped erode its support among regional powers over the past decade. In 2018, Saudi Arabia went so far as to arrest some Hamas members living in the kingdom. Of its previous Arab backers, only Qatar continued to actively support Hamas.

In recent years, however, Hamas has softened its rhetoric against the Assad regime in Syria, an Iranian ally, and increased coordination and cooperation with Hezbollah, another Iranian ally. Iran has encouraged this sort of direct relationship between its various allies in the region. This common cause with Tehran was apparent when the US assassinated General Qasem Soleimani, the commander of the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, in January 2020. Hamas raised his photo throughout the Gaza Strip in commemoration, while supporters of the Houthis in Yemen and Hezbollah in Lebanon did likewise.

During the most recent confrontations between Hamas and Israel, the Houthis collected donations for Hamas and organized marches. Mohammed al-Houthi famously donated his dagger (an expensive Yemeni jambiya) to the Palestinian resistance. Hamas’ representative in Yemen, Mouath Abu Shemala, responded by publicly honoring Mohammad al-Houthi with a plaque to commemorate the Houthis’ support for Hamas. Islah and others within Yemen’s anti-Houthi coalition immediately cried foul, complaining that Hamas could not support both Islah and the group’s arch-rival. Hamas responded in a statement that Abu Shemala’s action was a “personal decision that did not express the views of the group and its leadership in any way.”

Most recently, the Houthi movement has used this apparent repproachment with Hamas to also embarrass Riyadh, attempting to make it look like Saudi Arabia opposes the Palestinian cause: in August 2021, Houthi leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi stated that the group was ready to release Saudi and Yemeni prisoners in exchange for Riyadh releasing detainees from Hamas.

Hamas’ detente with the Houthis does not necessarily mean that it is abandoning its relations with Islah and the Muslim Brotherhood. Outside of Houthi controlled territory, Hamas continues to reach out to and interact with Islah and other Yemeni supporters, however its popularity has been marred due to its resumption of ties with the Houthis. Islah, for instance, has condemned the alignment. Looking ahead, Hamas faces a tricky path in Yemen staying friends with sides who are enemies.

Tawfeek Al-Ganad is the Arabic Editor for the Sana’a Center.

This commentary is part of a series of publications by the Sana’a Center examining the roles of state and non-state foreign actors in Yemen.

In Focus

Protest of the Walls

By ThiYazan Al-Alawi

I have been drawing on Sana’a’s walls for years. In 2012, when I was a high school student, I launched my first art campaign: “Caricature of the street.” I used to save up my allowance to draw in the streets as a way of expressing my opinion and echoing what the youth of the Arab Spring revolutions were doing. My murals highlighted a range of issues from politics and the crimes of Al-Qaeda to famine and censorship, which directly impact me as an individual in the community and as an artist.

Over time, my fingertips got accustomed to the brush until it became like a sixth finger. I was addicted to the smell of paint. I’d stand for hours drawing, wrapped up in the dream of freedom of speech and change. Each color meant a lot to me. Every line, dot, and shape made me more aware of the importance of art and how to reflect reality in a street mural.

The National Dialogue Conference

Beginning in 2014, people started to stop and ask me what I was drawing; I’d respond with the enthusiasm of the novice, saying I was expressing myself by drawing a caricature about the National Dialogue Conference, the post-revolution transition process that began the previous year. My drawing was a dream to resolve Yemen’s long-standing problems. Some thought the mural represented a pessimistic view, but I observed the situation and predicted the failure of dialogue. The way the international community was dealing with Yemen was thoughtless and rash, and ignored the conflict that was happening outside the conference’s halls.

A Dose of Art and Life

After the Houthis entered Sana’a in September 2014, I launched a new art and social campaign called “Art and life” aimed at strengthening community peace. I drew the faces of 21 of Yemen’s most prominent singers, as a tribute to these artists and the cultural heritage they have imparted. First, I drew the faces on paper then in black on the walls. Several friends and passersby gathered around and helped paint, using the colors of art and life. Our laughs echoed in the street while we documented a significant art phase in Yemen’s modern history. It was a carnival of colors, celebrating these figures whose songs we still listen to until this day. The voices of these singers are an integral part of societal memory and cultural heritage for Yemenis, whether in the fields, rural areas or city streets. I considered it my duty as an artist to document something we are proud of, something that should be protected and spread everywhere.

Peaceful Revolution on the Walls

Later, in December 2014, I drew a mural on Al-Qeyada Street documenting the slogans and civil demands of Yemeni youth. These slogans have a value that will continue to exist despite the changes in the political situation in the country. The tents and squares of the revolution may be empty, but these murals serve as documentation of the peaceful protests that changed Yemen. I used to say: “If the voice of the youth goes silent in the street, the walls will continue to speak.” I still believe this. The campaign, “Caricature of the street,” bore witness to the situation from 2012 until September 2014, a phase that was characterized by the participation of the youth in many fields, and by freedom of opinion and expression.

A New “Divided” Yemen

Ever since the Houthis seized the capital Sana’a in September 2014, I felt a sense of responsibility. The Houthis were not the only thing that raised my fears during this period. I went out to the street two weeks before the launch of Operation Decisive Storm in March 2015 to paint murals about foreign interventions on Al-Sabaeen Street. I drew two cold figures moving chess pieces on a board in the shape of Yemen’s map, divided into squares. I did not know then I was predicting a new foreign intervention that would tear my country apart.

Color on Dried Out Newspaper

For a while I stopped drawing. I did not know how to resume my art activity. During the first months of Operation Decisive Storm, Sana’a became a ghost town. Streets were deserted and people were scared. The silence was what frightened me the most. There wasn’t room for art or life when there was war. The issues I drew about seemed marginal compared to things like famine, displacement and constant death. Daily life changed in every way. The city was no longer tolerant of newspapers or views that opposed the Houthi movement.

And just like war chooses its victims, it also chooses its merchants. I wondered how I, as a painter, could maintain the brightness of my colors and not sink in despair or hatred. How could I continue to draw based on my slogan that art is part of my daily life? How could I depict the humanitarian suffering that struck us?

Sometimes, I wondered how I could draw when people were starving and asked myself if my art would make any difference. I did not know the answer but I knew that I had to draw. I had to document what I was seeing. I thought of how to proceed with my art. Since all newspapers were banned in Sana’a, I decided to reproduce the newspaper and turn it into a protest poster. I looked for newspapers at kiosks and shops and eventually I found some that I could reuse as canvases for my art.

When I first started drawing, my aim was to go to the street to express my opinion and enjoy drawing. Today when I go to the street I hide my paints and I’m afraid of being stopped. But Yemen is full of events, crimes and stories which the world must not forget. Art is a duty. I must document what I am living. Every second I live is a second I feel I must draw for the future. One day the war will end. The walls may go back to how they were and the world will forget what we lived through. My hope is that these murals and other works of art remain to narrate what the war put us through amid the world’s silence.

Thi Yazan Al-Alawi is a participant with the Sana’a Center’s Yemen Peace Forum. He is a Yemeni artist who has launched several campaigns and art projects on Yemeni streets since 2012.

Book Review

Disappeared: On Yemen, Yemenis, and Being Taken

A review of: The Tightening Dark: An American Hostage in Yemen by Sam Farran (and Benjamin Buchholz)

&

Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found in Guantanamo by Mansoor Adayfi

By: Brian O’Neill

A Yemeni in Afghanistan plunges into the black hole of Guantanamo. An American in Yemen vanishes into a prison suddenly run by Houthi militants. Two stories; two disappearances. Both are, in their own way, stories about stories, or the lack thereof. That’s the remarkable thing about having disappeared: the sudden lack of a narrative.

That’s one of the reasons disappearing is so frightening. Suddenly, your story is over. It’s being told by others. And so, for the vanished, for the captured, for the imprisoned, the need to impose narrative on life is important.

That need for narrative, to tell the story of being vanished, is told by two missing people in two very different circumstances in two very different ways. Sam Farran, an ex-Marine and private security consultant, was held in Sana’a by the ascendent armed Houthi movement for seven months. Mansoor Adayfi, a Yemeni caught up in Afghanistan, was in Guantanamo for 14 years.

These are extremely different stories. One is of someone crushed by a distant power, ground underneath a global “war on terror”, held without legal recourse by the most powerful country in the world. The other is a story about someone who was used to wielding that power and who was suddenly rendered helpless. Both are filled with terror, but hit very different notes.

Those notes are defined by a sense of power. Those who have it can tell their own story exactly as they want to, and make sure everyone else is a side character. Those who have no power have to strive to understand what is going on with them, even if their world is made small and dark and violent. In that way, it is no different than the Western media focusing on the politics of war in Yemen or Afghanistan while ignoring the human wreckage.

These, then, are stories about war and its consequences. They are about who gets swept up in the wreckage of war and who gets to do the sweeping. They are also about who is considered important, and who is not. Ultimately, they are about how power gets to shape its own narrative, even for those who were at one time, even relatively briefly, powerless.

Mansoor Adayfi and the Terrors of Guantanamo

“Torture”, Adayfi write, early in the book, “corrodes your memory and your sense of time.” If anyone should know, it is him. Captured in Afghanistan early in the US invasion, in 2001, Adayfi was part of the vast unwilling exodus of prisoners being disappeared from the country (darkly mirroring the recent exodus at the end of the war’s American chapter).

Adayfi’s story is that he was a student on a visa, and was sold by a warlord to the Americans. This rings plausible, of course, as the CIA was hoovering up anyone labeled as Al-Qaeda by, well, anyone. The American narrative, based on his release hearing, contradicts this, saying he was a fighter affiliated with Al-Qaeda, but had reformed (or become compliant) enough to be released to a third-party country.

Adayfi’s story is that he was a student on a visa, and was sold by a warlord to the Americans. This rings plausible, of course, as the CIA was hoovering up anyone labeled as Al-Qaeda by, well, anyone. The American narrative, based on his release hearing, contradicts this, saying he was a fighter affiliated with Al-Qaeda, but had reformed (or become compliant) enough to be released to a third-party country.

What happened in between those years – and the gap between those stories – is what drives his brutal, painful, grimly repetitive, and sometimes stirring and funny recollections. The heart of it is that, in his telling, he’s accused of being a much older Egyptian general who worked directly with Al-Qaeda. The Americans believed that narrative, or at the very least were incentivized to prove it, and so did everything they could to get him to admit it.

This isn’t about stress tests. It’s not a good cop/bad cop thing. The prisoners in Guantanamo were treated as absolutely less than human, as vicious monsters. Beaten every day, interrogated, left in solitary for months, and subject to cruelties both petty and monstrous.

There is, in any book about prison and captivity, the repetition. That’s sort of the point. There are phrases that repeat throughout the book (“they rushed my cell and began beating me”, “they searched my genitals in the worst possible way”) that are almost like mantras. That’s part of breaking people, and it was done so that they could confirm a story.

The tortures were sometimes more sadistically imaginative. One thing that struck me was how Adafyi told of weekly sing-alongs between prisoners, a small glimpse of humanity. To stop this, the torturers ordered dozens or more industrial vacuum cleaners to drown them out. They also put the vacuums just outside of the tiny cells in the solitary confinement building, so that the mechanized roar filled your head, day after nightless, sleepless day.

Guantanamo was about making people disappear. It was deliberately meant to vanish human beings. The site was selected because it was outside the jurisdictions of US courts. 90 miles from the mainland, it was an absolutely black hole. It was meant to make sure that no screams were heard, no faces were seen and no stories were told.

One of the key villains of the book is Geoffrey Miller, a general who also oversaw Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Miller, (who has been charged with war crimes in European courts), was seen as deliberately cruel. At no point, in Adayfi’s narrative, did he see the prisoners as human, but rather as animals who needed to be beaten and broken. It was under his watch that the most excessive cruelty ran rampant.

However, Miller oddly provided some of the book’s best moments, as the prisoners tried to make his life hell, taunting him and hurling waste at him. They played pranks on him and tried to embarrass him. They came up with nicknames for him – Adayfi refers to him as “the big chicken Miller” over and over – and tried to show that they weren’t afraid. In this way, they reclaimed a bit of their narrative from someone who tried to take all of it away.

This is taking something back. It’s reclaiming Adayfi’s humanity and turning the tables on someone who saw him as flesh to be rendered in exchange for information. Bit by bit, fight by fight (and Adayfi did fight, constantly, which made him be seen as the “worst of the worst”), more rights were gained and they were treated more decently. Eventually, through political changes, through legal activism and action, and through sheer force of will, Adafyi was able to make his story heard.

This was a common theme, and it is the heart of Adafyi’s life. Though his post-prison life has been difficult (more on that below), he has worked to tell his stories and others. Whether it was convincing guards that one prisoner was a storm-summoning demon, or finally escaping the vacuum torture by pretending to be in love with it, he reclaimed his story. And he did so because, as he told it, “Americans were ready to believe anything but the truth.”

An American Contractor in Yemen

Talking about life is no problem for Sam Farran, a gregarious storyteller with a tale to tell. The tale, eventually, is being taken hostage by the Houthis after they swept into Sana’a in 2014. To get there, we have a long story about his path – the book is far more a memoir of an unusual life than a hostage story. It’s told by someone who is used to being heard.

Farran was born in southern Lebanon, and describes an idyllic pre-civil war childhood. His family moves, eventually ending up running a successful restaurant in Benghazi, Libya, before the young Farran begins being noticed by Palestinian Liberation Organization exiles, and the family sweeps up to Michigan, to a town with a large Arab population.

Farran was born in southern Lebanon, and describes an idyllic pre-civil war childhood. His family moves, eventually ending up running a successful restaurant in Benghazi, Libya, before the young Farran begins being noticed by Palestinian Liberation Organization exiles, and the family sweeps up to Michigan, to a town with a large Arab population.

Farran becomes Americanized, to an extent. He joins the Marines when he is old enough. He has some struggle with “anti-Muslim rhetoric” and people giving him a hard time, but he gives it back. In a telling moment, he’s accused of cheating on an Arabic-language test (even though he’s livid he missed two questions) and is so offended he leaves a translator program.

It’s a fairly shaggy story, albeit an enjoyable one that begins to become more clear and compelling as it moves closer to the ‘War on Terror’. The 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center gives him a chance to use his language skills, and the 2000 attack on the USS Cole brings him closer to (though not yet in) Yemen. Finally, after 9/11, which is mentioned more or less in passing, his life kicks into high gear.