The Sana’a Center Editorial

Public Executions in Sana’a Herald Houthi Reign of Terror

Yemenis have become well acquainted with death and the many faces of injustice during these past seven years of war, but the Houthi movement’s September 18 public execution of eight men and a teenager staked claim to a new level of horror. With it, the Houthis sent a clear and unambiguous message to ordinary Yemenis of their intent to cement their rule through terrorizing society into submission.

The nine victims, all from the western Tihama region, were neither politicians nor activists or journalists, but ordinary people plucked from their ordinary lives to serve as a message to all Yemenis. They were convicted in a secretive sham “trial” of providing the coordinates for an Emirati drone strike that killed Saleh al-Sammad, then-president of the Houthis’ Supreme Political Council, in Hudaydah in April 2018. Three years after their detention, based solely on confessions secured through torture and their presence at a rally attended by Al-Sammad, they were slaughtered in one of Yemen’s most famous and revered public spaces, Al-Tahrir Square.

The Houthi organizers sought a festive atmosphere for their spectacle of death, with children present, music blaring for the crowds and cameras capturing the scene as the executioners pumped bullets into the bodies of the eight men. The teenager among the nine condemned, Abdulaziz Ali al-Aswad, had been arrested at just 13-years-old and so tortured during his three years in Houthi custody that he had been partially paralyzed and had to be carried by his killers to his terrifying end. The Houthis had intended to execute a tenth man at the event, Ali Abdo Kazaba, but he reportedly did not live long enough at the hands of his interrogators to attend.

Houthi rule already had set the country back decades, with the group crushing Yemen’s vibrant media, throttling civil society and silencing the many voices and parties that had made the capital city’s political scene relatively active and free-speaking. Even after seven years of this though, the horrific scenes the Houthis proudly celebrated this month had been unthinkable. Yemenis were stunned.

The Yemeni judiciary has rarely been just. The criminal courts have long been known for legal violations and selective enforcement. Since the Houthi takeover of Sana’a in 2014 they have also shown an increasing zeal for capital punishment. This month’s officially sanctioned brutality, however, set a new precedent, clearly positioning the courts as a weapon of state terror the Houthis will wield upon the population. It also entails worrying political and diplomatic implications. The Houthis clearly have become unabashedly confident in practicing power their way, which runs in direct contradiction to the concepts of social and political partnership they have often spoken about and which are considered essential for any possible political settlement to the war.

The reactions of the United Nations, the United States, the European Union, and other international stakeholders in the ongoing conflict were paltry in the shadow of this atrocity, issuing statements with words that are empty and forgettable without action to back them. Such will only embolden the Houthis. Dozens of other Yemenis currently in Houthi custody are facing death sentences, while anxiety runs wild among those who might be the next targets for Houthi ‘justice’.

Besides Al-Aswad, on September 18 the Houthis unjustly executed Moaz Abdul Rahman Abdullah Abbas, Ibrahim Mohammed Abdullah Aqel, Abdul-Malik Ahmed Hamid, Mohammed Khaled Haig, Mohammed Mohammed Ali Al-Mashkhari, Mohammed Yahya Muhammad Noah, Ali Ali Ibrahim Al-Quzi, and Mohammed Ibrahim Al-Quzi. The names of these ordinary people, who along with Kazaba were largely overlooked while in Houthi custody, should be known and remembered because their deaths made it undeniably clear just what sort of post-conflict society the Houthis envision if the world accepts and recognizes their “governance”.

Contents

-

Houthis Forces Press Onslaught in Marib

- Analysis: Tribes Bear the Brunt of Houthi Advances – By Ali al-Sakani

- Commentary: The Houthis’ Fatal Military Success – By Abdulghani Al-Iryani

-

Southern Streets Erupts in Protest

- Analysis: STC, Yemeni Government Face Public Outrage – By Hashem Khaled

- Commentary: The South’s Hot Summer – By Hussam Radman

-

Education to Indoctrination Under the Houthis

- Commentary: How the Houthis Seized and Remade the Education System – By Salam al-Harbi

- Analysis: Curriculum Changes to Mold the Jihadis of Tomorrow – By Manal Ghanem

-

Al-Qaeda in Yemen

- Analysis: Where is AQAP Now? – By Elisabeth Kendall

September at a Glance

The Political Arena

By Casey Coombs

Developments in Government-Controlled Territory

Houthis Bomb Mokha Port

On September 11, at least two Houthi missiles and four bomb-laden drones struck the port in the Red Sea city of Mokha in Taiz governorate. The attack, which took place on the day the port was scheduled to open to food imports, destroyed port infrastructure and ignited warehouses storing humanitarian supplies, according to a statement by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the internationally recognized government. Local authorities had recently completed rehabilitation of the port in anticipation of the resumption of commercial and aid imports. The attack also brought attention to a new airstrip under construction near the port.

Mokha is under the control of Brigadier General Tareq Saleh, commander of the UAE-backed National Resistance Forces. In mid-June, following the discovery of satellite images showing a newly built airbase on Yemen’s Mayun island near the Bab al-Mandab Strait, Saleh claimed that his Emirati-backed troops were stationed there.

On September 19, generators for a 12 megawatt power station arrived at Mokha port. The generators were then transferred from the port to the Mokha power station site and are expected to be used to help provide electricity to Mokha city.

Tribes, UAE-Backed Forces in Standoff in Shabwa

On September 6, Emirati warplanes flew at low altitude over Shabwa governorate’s capital, Ataq, where Mihdhar tribesmen had blocked a convoy of UAE-trained Shabwani Elite forces from reaching Al-Alam military base in Jardan district, northeast of Ataq. The convoy was traveling from another UAE-supported military base located in the Balhaf liquified natural gas (LNG) export facility on Shabwa’s southern coast. The Mihdhar tribe from Markah al-Sufla district erected the roadblock to demand accountability for the Shabwani Elite’s killing of some of its members, including a minor, during clashes in 2019.

In early August, Shabwa’s local authority, led by Shabwa Governor Mohammed Saleh bin Adio, voted to reopen the LNG export terminal, which Emirati and Shabwani Elite forces have used as a military base for nearly five years. Later in the month, government forces loyal to Bin Adio set up two checkpoints around the LNG facility and arrested several Shabwani Elite soldiers. Saudi mediators negotiated an end to the standoff, but the parties have yet to agree on when Emirati forces would vacate the Balhaf facility, the largest investment project in Yemen’s history.

Yemeni-American Student, MSF Nurse, Murdered at Lahj Checkpoints

On September 8, Yemeni-American expatriate Abdelmalek al-Sanabani, 30, was detained by Southern Transitional Council (STC) forces in Lahj governorate while taking a taxi from Aden airport to his family’s home in Dhamar governorate. The soldiers, who belong to the 9th Thunderbolt Brigade in Tur al-Bahah district, accused al-Sanabani of having ties to the Houthis, stole the large amount of cash he was carrying and killed him. The incident prompted widespread public outrage in Yemen.

In the same district in Lahj, on October 4, Atef Seif Mohammed al-Harazi, a 35-year-old nurse working with Doctors Without Borders, was also killed at a checkpoint. The incident occurred on the road to the technical institute in Tur al-Bahah that has frequently been blocked by bandits, who are known to the local authorities, according to a memo obtained from the office of the district’s director-general. Atef, who worked at a general hospital in Dhi Sufal district in Ibb governorate, was returning from a trip to Aden with a friend when he was killed.

STC Chief Declares State of Emergency as Protests Sweep Aden, Southern Cities

On September 13, demonstrators took to the streets of Aden to protest a lack of services and deteriorating conditions in the interim capital. STC forces fired on protesters after they attempted to storm STC headquarters. Three protesters were killed and several injured during several days of confrontations. On September 15, as street protests were spreading in other cities across the south, STC President Aiderous al-Zubaidi declared a state of emergency in southern governorates and called on the security forces to strike anyone seeking to destabilize security and stability with an iron fist. STC officials justified the emergency declaration as a response to Houthi advances into the south, which they claimed were part of a conspiracy with the Islah party. (For details on the protests that swept southern Yemen in September, see ‘STC, Yemeni Government Face Public Outrage’ and ‘The South’s Hot Summer’.)

Government Forces in Marib Arrest Prominent Human Rights Activist

On September 13, military forces in Marib governorate arrested human rights activist Amatullah al-Hammadi, an employee of the Danish Refugee Council in Marib governorate. Al-Hammadi, who is being held at the Political Security prison in Marib, was arrested “without regard to the legal procedures stipulated in the Code of Criminal Procedure,” according to a statement by the Marib-based Abductees’ Mothers Association.

PM Maeen Abdelmalek Returns to Aden

On September 28, Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed returned to the interim capital after a months-long absence. The prime minister’s decision to return to Aden has caused a rift between him and President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, according to three senior government officials who spoke with the Sana’a Center. Hadi reportedly opposed the prime minister returning to the interim capital without receiving any concessions from the STC.

Saeed’s newly formed cabinet initially arrived in Aden in late December in what appeared to be a breakthrough in the implementation of the power-sharing Riyadh Agreement aimed at settling differences between the internationally recognized government and the STC. Less than three months later, Cabinet members affiliated with the internationally recognized government left the interim capital after STC-aligned protesters stormed the presidential palace, the seat of the government in the city. A key sticking point in the implementation of the Riyadh Agreement has been the sequencing of its political and security provisions. The government has demanded that the STC bring its forces under the control of the Interior and Defense ministries before returning to Aden and carrying out political and economic reforms, with the latter including activation of the Supreme Economic Council and the Central Authority for Oversight and Accountability as well as streamlining tax collection. The STC has insisted reforms precede security measures.

Government and Houthi Forces Swap Prisoners in Taiz

More than 200 prisoners were released as part of a deal between Houthi forces and the pro-Islah Taiz Military Axis in Taiz governorate. Houthi-run Saba news agency said the group released 136 “mercenaries” in exchange for 70 Houthi fighters. The media center of the Taiz Military Axis said that most of 136 prisoners whose release it secured were “civilians who were kidnapped by the Houthi militia from the streets and checkpoints.”

UN-sponsored negotiations seeking an all-for-all exchange of prisoners between the Houthis and the internationally recognized government have struggled to gain traction since the initiative was included as part of the December 2018 Stockholm Agreement.

Developments in Houthi-Controlled Territory

Houthis Detain More Musicians

On September 7, Houthi authorities detained popular Yemeni folk singer Yousef al-Badji in front of his home in Sana’a, according to a post on his Facebook page. Al-Badji claimed he was arrested for appearing on the “Guests of Art” TV program on Yemen Shabab satellite channel. A week earlier, Houthi gunmen detained another Yemeni folk singer, Asel Abubaker, at a wedding hall, reportedly for violating a ban on wedding singing. In recent months, authorities throughout Houthi-held areas have banned musicians and singing at weddings, which they claim conflict with conservative religious practices.

Houthi Publicly Execute Eight Men and a Teenager

On September 17, a Houthi-run court upheld the conviction of nine people alleged to have participated in the assassination of the former president of the Houthi Supreme Political Council, Saleh Ali al-Sammad, who was killed in a UAE-drone strike in 2018. The nine individuals were publicly executed the next day in Al-Tahrir square in Sana’a. One of them, a 17-year-old, was paralyzed from torture in Houthi detention. All of the men testified that they were coerced during torture to make false confessions. A tenth man tried in the same case died from torture on August 7, 2019, according to a statement by the Abductees’ Mothers Association. (See ‘The Sana’a Center Editorial: Public Executions Herald Houthi Reign of Terror‘)

Local Houthi Authorities Restrict Women’s Rights

A memo circulating on social media on September 23 outlined new restrictions on women in the village of Ghadran in the Bani Hushaysh district of Sana’a. The memo, signed by Houthi supervisors (mushrafeen) and senior tribal loyalists, banned women from several activities, including working with relief organizations and using smartphones and cosmetics, calling these activities an “ideological invasion” by the Saudi-led coalition. Men who allow their wife, daughter or any female they are the guardian of a smartphone will be subject to fines of 200,000 Yemeni rials and a cow, according to the memo.

International Developments

New UN Special Envoy for Yemen Addresses Security Council

On September 10, Hans Grundberg made his first address to the UN Security Council as the UN Secretary-General’s special envoy for Yemen. Grundberg said the country was “stuck in an indefinite state of war.” Noting that the warring parties had not discussed a comprehensive settlement since 2016, Grundberg said there were “no quick wins” in the civil war. In formulating a strategy to carry out his mandate, Grundberg said he plans to review what has and has not worked and “listen to as many Yemeni men and women as possible,” adding that his initial consultations with Yemenis and key regional and international parties “will soon start.”

Quad Meets Over Yemen’s Economic Situation

On September 15, the ambassadors to Yemen from Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the UK, and the US chargé d’affaires met in Riyadh to discuss the rapidly deteriorating economic conditions in the country. The four countries, known as “the Quad,” stressed the need for Cabinet officials in the internationally recognized government to return to Aden as quickly as possible to oversee future international support for economic recovery. (See ‘Economic Developments‘)

US Leftists Advance Bill to End Aid to Saudi War Effort in Yemen

On September 23, legislation aimed at “terminating US military logistical support, and the transfer of spare parts to Saudi warplanes” in Yemen passed the House of Representatives in a 218 to 206 vote. Introduced by Democratic Representative Ro Khanna and Independent Senator Bernie Sanders, the amendment will be included in the National Defense Authorization Act for 2022 if it passes the Senate.

Iranian General Names Houthis Member of Iran’s Regional Deterrence Network

On September 25, Iranian General Gholamali Rashid said in a speech commemorating the Iran-Iraq war that Houthi forces represent one of six armies beyond Iranian borders that would fight for Tehran. Rashid said that Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force commander, General Qasem Soleimani told the Iranian joint military command: “I have assembled for you six armies outside of Iran’s territory, and I have created a corridor 1,500 kilometers long and 1,000 kilometers wide, all the way to the shores of the Mediterranean Sea.” Speaking three months before he was killed in a US drone strike on January 3, 2020, Soleimani listed the forces as Hezbullah in Lebanon, Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) in Palestine, an army in Syria, the Popular Mobilization Forces in Iraq and Ansar Allah, or the Houthis, in Yemen, according to Rashid.

Top US National Security Official Meets Saudi Crown Prince On Yemen War

On September 28, US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan and other senior officials met with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to discuss efforts to end the conflict in Yemen. According to a Saudi Press Agency statement, Bin Salman said the kingdom was committed to the peace plan it proposed in March aimed at ending the conflict. The Saudi plan entailed a comprehensive cease-fire under UN supervision, allowing oil tankers to enter Hudaydah port, opening Sana’a airport to flights to and from selected destinations and kickstarting political talks between Yemen’s warring parties to end the war based on the 2011 GCC deal, the outcomes of the 2013 National Dialogue and UN Security Council resolutions. The Houthis rejected the offer in March, saying it didn’t go far enough.

At the United Nations

UN General Assembly Convenes in New York

From September 21-27, the United Nations General Assembly convened for its annual debate at UN headquarters in New York, holding a series of high-level meetings and side events to discuss global policy-making challenges. Yemen’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ahmad bin Mubarak, delivered a speech in place of President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, pledging cooperation with the incoming UN Special Envoy to Yemen, Hans Grundberg, requesting additional coronavirus vaccines and condemning human rights violations committed by the armed Houthi movement. Bin Mubarak also called on the international community to take specific measures to help Yemen’s spiraling economy: Exert more pressure on the Houthis to use taxes collected to pay for public services, help stem the devaluation of the Yemeni riyal, channel aid to development projects and support the Central Bank of Yemen’s branch in Aden.

Representatives of regional powers and backers of the warring parties outlined Yemen priorities in their speeches to the general assembly. Saudi Arabia and the UAE blamed the Houthis for obstructing peace while praising Riyadh’s peace initiative in March, the conditions of which the Houthis rejected. Iran echoed the Houthi position by recommending an unconditional end to fighting and the opening of Houthi-controlled aid channels like Hudaydah port. Oman emphasized working with Yemen, US, UN and Saudi partners toward peace.

Donors Conference at UN General Assembly Raises New Funds

On September 22, the European Union, Sweden and Switzerland organized a high-level donor event on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly debate, to raise funds for Yemen’s humanitarian aid operations. Going into the event, less than half of the $3.85 billion requested for Yemen’s Humanitarian Response Plan in 2021 had been received, leading the UN to plan for food aid cuts in October. The event secured about $600 million in additional aid pledges. The largest donors included the US ($291 million), the EU ($140 million), Saudi Arabia ($90 million) and Germany ($58 million). As of October 7, total funding for Yemen’s 2021 humanitarian response plan stood at $2.72 billion paid.

Group of Eminent Experts Delivers Final Yemen Report

On September 28, the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen published its latest report. As in previous years, the experts said there were reasonable grounds to believe that the warring parties had committed war crimes. The document included an updated annex mapping the main warring parties. On October 7, the UN Human Rights Council voted not to extend the mandate of the eminent experts group for the coming year. On October 8, the group of experts released a statement criticizing the vote.

Casey Coombs is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies and an independent journalist focused on Yemen. He tweets @Macoombs

State of the War

By Abubakr al-Shamahi

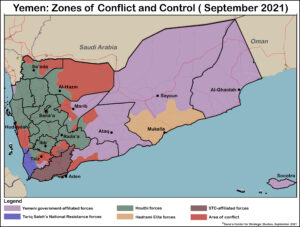

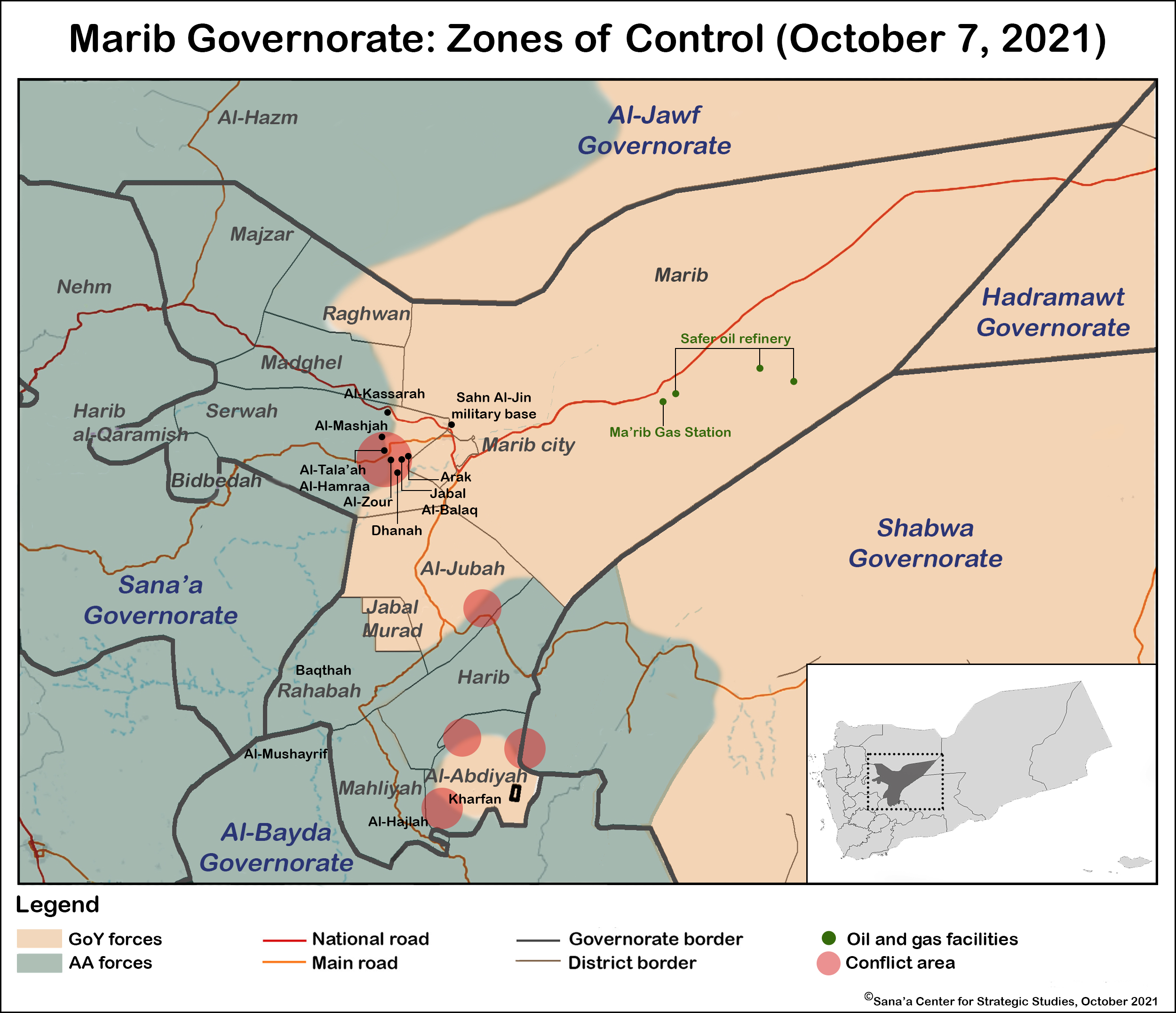

Houthis Capture Al-Bayda; Government Forces Retreat in Marib and Shabwa

The Houthis achieved notable successes against Yemeni government forces in September, taking full control of central Yemen’s Al-Bayda governorate as well as advancing farther into western Shabwa and southern Marib. There are currently few signs that the Yemeni government forces will be able to reverse the Houthi gains. Nor is the government likely to be able to stop the group from taking additional territory, as the Houthis encircled government forces and allied tribal fighters in places including Al-Abdiyah district in Marib.

September began with an advance by the Houthis from Al-Bayda into southern Marib’s Rahabah district on September 1, which government forces had captured from the Houthis in July. By September 8, the Houthis had retaken full control of the district, with government forces retreating to Jabal Murad. Sources on the ground told the Sana’a Center that a key reason for the quick defeat of pro-government forces in Rahabah was divisions between Murad tribal leaders, with Murad tribesmen making up the bulk of the pro-government forces in the area. A perception exists among these forces of inadequate support from the Yemeni government as the battle for Marib becomes a war of attrition and local tribal manpower dwindles (see ‘Tribes Bear the Brunt of Houthi Advances‘ and ‘The Houthis’ Fatal Military Success‘).

Following the takeover of Rahabah, the Houthis turned their attention east to Marib’s Harib district. The Houthis achieved this thanks to advances made in Shabwa’s western Bayhan district, which borders both Al-Bayda to the west and Marib to the north. By mid-September, the Houthis had advanced in several areas in western Bayhan, such as Nate’ Dabash, Dabah, Al-Kar’a, and Aqabat Amquah, according to local sources. The capture of the latter area left Houthi forces controlling the road linking Merkhah al-Ulya district in Shabwa and Maswarah district in Al-Bayda. The Houthis also opened up a new frontline in Khawrah, along the Al-Bayda-Shabwa border, and advanced into Merkhah al-Sufla district.

The Houthi advances in Shabwa, which had been securely in the hands of Yemeni government forces, opened up a new pathway for the Houthis into southern Marib. Harib district, which includes Harib city, the second largest urban center in Marib governorate, fell to the Houthis on September 22, after the group attacked from Shabwa’s Al-Ain district. The Yemeni government’s chief official in Harib district, Naser al-Quhati al-Muradi, was killed in fighting with the Houthis the day before.

The capture of Harib cut the only remaining supply line to Al-Abdiyah district, also in southern Marib. Beginning on September 22, Houthi forces besieged the district from all sides, preventing any food or goods from entering. Pro-government tribal forces in Al-Abdiyah have held out against the Houthis since 2015, but the situation in the district was becoming more difficult. On September 25, tribal mediators negotiated a deal in which Houthi forces would allow civilians from Al-Abdiyah to purchase food and goods from the neighboring Houthi-held Mahliyah district, according to local sources.

The Houthi advances in southern Marib and western Shabwa were in large part a consequence of a Houthi counter-offensive in Al-Bayda governorate that began in mid-July to push back gains government forces had made earlier that month. Some of the areas captured by the Houthis in Al-Bayda bordered Marib and Shabwa, and allowed the group to open up new fronts and push deeper into Yemeni government-held territory. Houthi advances into Al-Bayda continued unabated in September, and after renewed attacks on Al-Sawma’ah and Maswarah districts in the second half of the month, the group announced that they had full control of the governorate on September 23, a significant blow to the Yemeni government.

Government forces are now more concerned with safeguarding the territory they have than reversing the most recent Houthi gains. Marib’s oil and gas infrastructure is a tempting target for the Houthis following the fall of Harib, although the Saudi-led coalition may be able to defend the largest facilities with airstrikes because they lie in the open desert and lack cover. Marib city remains under threat from Houthi forces, with fighting on frontlines to its west continuing without much movement for either side. Houthi missiles also have continued to strike Marib city and its surroundings; a September 25 attack targeted the home of Marib governor Sultan Al-Aradah in Marib al-Wadi district, killing four civilians. In Abyan, now that the Houthis have consolidated their control over the neighboring Al-Bayda governorate, government and STC forces may be forced to put their rivalry aside if they want to keep the Houthis out. In Shabwa, government forces will likely focus on stopping the Houthi advance in Bayhan, and keeping hold of the Jannat oil field, which is at risk of Houthi capture.

Coalition Airstrikes Resume in Taiz

The Saudi-led coalition launched its first airstrikes in the vicinity of Taiz city since 2018 on September 8, targeting Houthi positions in Al-Janad area and at Taiz airport, in eastern Al-Taiziyah district. The airstrikes, which came after the Houthis reportedly launched missiles from the area at Al-Anad base in Lahj on August 29, killed a number of Houthi fighters, including Abu Kenan, a commander at the airport and 16th Street area, according to Yemeni government military sources who spoke to the Sana’a Center.

A separate Houthi aerial assault targeted the Joint Forces, which are backed by the Saudi-led coalition, in Al-Mokha on September 11, the night the city’s port had been scheduled to reopen. The attack destroyed a fuel storage tank at the port. Yemeni government officials blamed the Houthis for the attack.

Houthi Missile Attack Kills 12 in Hajjah

A Houthi missile attack killed at least 12 people at an event marking the anniversary of the 1962 North Yemen revolution held by pro-government forces in Midi, western Hajjah. Among the deceased were Brigadier General Ali Mater, a commander in the government’s 5th Military Region, Colonel Abdullah Tarmoum, the head of the government’s Hajjah police operations, and Colonel Ali Abu Qahm, the director of security for the government in Midi district.

Abubakr al-Shamahi is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies.

Economic Developments

By the Sana’a Center Economic Unit

Collapsing Currency, Living Conditions Spur Widespread Protests in South Yemen

During September, the level of protests, general strikes and other civil unrest notably increased in areas controlled by the internationally recognized Yemeni government. Citizens as well as public and privately owned entities across southern, central and eastern Yemen called for immediate government intervention to halt the rapid decline in economic and living conditions.

The historic depreciation of the Yemeni rial (YR) and subsequent further reduction of purchasing power in areas that are nominally under government control are among the main sources of discontent. On September 26, the value of the rial fell to YR1,200 per US$1.

The depreciation can be partly attributed to recent Houthi battlefield advances; as the Yemeni government loses ground, people in south Yemen and Marib are increasingly fearful that CBY-Aden-printed banknotes they hold will become worthless and are rushing to exchange them for hard currency.

Persistent electricity outages represent another key factor motivating the outcry in Mukalla, Aden and elsewhere. Frustration over an unreliable and often sparse supply of electricity cyclically rises during the hotter, more humid summer months, when local residents are forced to deal with challenging weather conditions without air conditioning. This year, however, the level of anger appears more intense, widespread and lasting than in previous years, as the array of socio-economic challenges that people face worsens. Meanwhile, the local currency crisis has plunged to new depths. Clashes between demonstrators and local security forces led to the death of protesters in Aden and Mukalla.

In addition to Aden and Hadramawt governorates, protests were staged in Abyan, Lahj, Shabwa and Taiz. Public and private sector entities took direct action in parallel, which could reduce economic and commercial output in government-run areas. These included:

- A body that represents merchants in Taiz declared a general strike on September 18. They warned of further escalation if solutions to the current economic crisis were not found.

- In Hadramawt, employees from the state-run energy company PetroMasila issued a letter on September 16 warning that they would take escalatory measures if PetroMasila did not respond to their demands for an improvement in their current living conditions. The employees called on the local authorities in Hadramawt, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor and the local trade union federation to intervene on their behalf.

- The local trade union in Al-Mahra governorate announced the start of a partial strike, which began September 21, and indicated that it would continue until the union’s demand was met for a 100 percent increase in employee salaries to offset the impact of the local currency depreciation.

- On September 26, the Association of National Petrol Station Owners issued a statement announcing the suspension of work at all privately owned fuel stations in Aden, Lahj, Abyan and Al-Dhalea, commencing on September 28, 2021.

YR Depreciation Creates Unprecedented Money Transfer Challenges

The unparalleled depreciation of the Yemeni rial (YR) outside Houthi-controlled areas had negative implications for people looking to transfer money within Yemen. On September 25, it was reported that the cost of transferring Yemeni rials from Aden to Sana’a exceeded the value of the money being sent. For example, the fee to send YR100,000 from Aden to Sana’a would be about YR102,000.

This significant cost is due to the widening divergence between the value of the rial in Houthi- and government-administered areas. While the currency depreciated to YR1,200 per US$1 on September 26, the rial in Houthi-run areas was trading at YR602 per US$1.

In response to this historic depreciation and the huge increase in the cost of transferring money to Houthi areas, the money exchange associations in Aden and Hadramawt announced a suspension of money transfer networks and activities until further notice.

Bank of England Unfreezes 82 Million Pounds

On September 27, the Central Bank in Aden announced that the Bank of England had decided to grant the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden) access to £82 million that had been frozen since 2016 as a result of the relocation of the central bank headquarters from Sana’a to Aden that fragmented the bank. The Central Bank in Sana’a issued a strongly worded statement in response to this development, denouncing the move and the legitimacy of the Central Bank in Aden.

Government Officials Discuss SDR Unit Options with World Bank

On September 2, Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed chaired a meeting with World Bank officials in which they examined the different options that could be explored concerning the use of the financial support the IMF allocated to Yemen in August. This support was in the form of Special Drawing Rights (SDR), the IMF’s supplementary central bank reserve asset, with the fund allocating Yemen SDR466.8 million, worth roughly US$665 million.

Features

Houthis Forces Press Onslaught in Marib

Tribes Bear the Brunt of Houthi Advances

By Ali al-Sakani

Over the past few weeks, Houthi forces have made the most significant advances in Marib governorate’s southern fronts in nearly a year.

On September 21, Houthi fighters took control of the Shabwa governorate districts of Ain and Bayhan as well as some parts of Usaylaan. A day later, the Houthis seized the center of Harib district, in neighboring Marib governorate. The director-general of Harib, Nasser al-Quhati al-Muradi, was killed on the first day of fighting, and the city, roughly 75 kilometers south of Marib city, fell without much fighting as government troops retreated 10 kilometers from the city center into the Mala’a mountains. Government forces were busy on other frontlines and did not appear to expect Harib city to fall. Establishing control over these areas allowed the Houthis to cut off the main highway between Shabwa and Marib.

Houthis Seek to Divide the Tribes

Harib city is the governorate’s second-largest city, and many students regularly travel to Marib city, the governorate capital, to attend Saba University. Female students may no longer be able to do so because of the fighting or because Houthi authorities won’t permit university buses carrying female students to pass.

In neighboring Al-Abdiyah district, home of the Bani Abd tribe, Houthi forces have not yet established control despite attacks throughout the year. Houthi forces’ battlefield momentum could push them toward Al-Jubah district, which is known as the southern gate to Marib city. Unlike Harib, where a variety of tribes and Hashemite families live, Al-Jubah is home to Marib governorate’s influential Murad tribe.

Since September 25, the Houthis have opened new fronts and intensified attacks along Al-Jubah’s southern and western borders with the aim of seizing three strategic sites: Am Raish camp near the Mala’a front, which overlooks the main highway between al-Jubah and Harib; nearby Al-Khashinah camp in Al-Jubah, about 2 kilometers from its border with Harib; and the western Alfa front in Rahaba district, about 2 kilometers from its border with Al-Jubah. On October 10, Houthi forces captured Al-Khashinah camp.

The Houthis are trying to break the Murad tribe for a number of reasons. Murad is the biggest Shafei Sunni tribe in Marib governorate and in the Madhaj tribal confederation; it also has a long history of resisting Zaidi inroads into the area. Ali Nasser al-Qardae’i, one of the most prominent sheikhs in Murad history, assassinated Imam Yahya Hamid al-Deen, ruler of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom, in 1948. Decades later, in 2014, former Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh pressed Ali al-Qibli Nimran, one of the most prominent Murad tribal and General People’s Congress party leaders in Marib, to join the Houthis or at least remain neutral so they could advance toward Marib city and seize the nearby oil fields in territory belonging to the Abdiah tribe to exact revenge against “our enemies,” a tribal source told the Sana’a Center.

Despite existing tribal disputes between Murad and Abidah, Nimran, who died in August 2021, rejected the offer and left the capital, Sana’a, to rejoin his tribe in Marib. He and his son, Abdulwahid al-Qabli Nimran, who now heads the GPC in Marib, allied with other anti-Houthi tribal forces and established wartime tribal camps known as matarh.

The Houthis are well-known for seeking to create and exploit divides among Marib tribes to take control of the governorate. However, at least so far, the more they have increased attacks in Marib, the more the tribes have united against them. Since the beginning of the Houthis’ large-scale offensive on Marib in January 2020, each tribe in the governorate has been mainly responsible for protecting its territory against them.

Houthi Strategy: Find the Weak Link in the Chain

For much of the past year, the Houthis have focused on advancing along three key fronts: Serwah, about 15 kilometers west of Marib city; Al-Kassarah and Raghwan, northwest of the capital; and Al-Alam fronts to the north along Marib’s border with Al-Jawf governorate. Although these frontlines are closer to the capital than any others in the governorate, they have failed to achieve a major military breakthrough due to the concentration of government and tribal defensive positions and heavy airstrikes.

With no prospects of a major breakthrough along these fronts, the Houthis adjusted their strategy in an attempt to gain territory along the more thinly defended southern frontlines in neighboring Al-Bayda governorate.

In July, Houthi forces managed to push the pro-government fighters out of Nat’e and Na’man districts in northeastern Al-Bayda along the borders of Marib and Shabwa, and then seized full control of Al-Bayda by reversing government gains in the governorate’s southeast district of Al-Sawma’ah. The Nat’e and Na’man frontlines were critical in protecting Shabwa and Marib from Houthi advances from the south and west. The breakthroughs allowed the group to open new fronts in Shabwa and pressure Marib from the south in September. These developments reflected a common Houthi tactic: When government forces manage to reinforce their defenses and repel attacks on one front, Houthis forces open a new front or attack elsewhere.

Despite ongoing heavy casualties, the Houthis have continued to push massive waves of fighters to the frontlines. If this fails to produce major breakthroughs, the Houthis risk losing the credibility and confidence among their supporters that helps recruit more fighters.

Tribes Try to Regroup

After the fall of Harib city, the influential Abidah tribes gathered in the presence of Governor Sultan al-Aradah, who is also a senior sheikh in the tribe, and decided to form new combat battalions to support government forces and defend the governorate. Meanwhile, the Al-Jeda’an tribes, located in northwestern Marib, mobilized fighters in matarh in their territory.

With mounting Houthi pressure on Murad fighters as well as on government forces in Al-Jubah and Harib, Abidah – their main rival – and Al-Jeda’an tribes sent tens of pickups carrying hundreds of fighters to support the Murad and army forces on the Ma’ala front between Al-Jubah and Harib. According to military and tribal sources, more than 500 Houthis and 100 anti-Houthi forces died in the fighting.

For tribes and government forces in Marib, the battle against the Houthis has become a fight to the death, with Houthi forces seeking to decapitate the anti-Houthi alliance’s leadership. A week ago, they targeted Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Sagheer bin Aziz with a ballistic missile in Al-Rawda neighborhood. In the early hours of September 26, Marib’s governor, Al-Aradah, survived a missile attack when two suspected Houthi missiles struck his house.

The unity of Marib’s tribes and its political, military and tribal leadership, along with the support of Saudi-led coalition airstrikes, have been crucial factors in resisting Houthi incursions and preventing the fall of the governorate. When government forces suffer a setback, the tribes send backup.

Ill Winds Blow for Anti-Houthi Forces

Although airstrikes by the Saudi-led coalition have played a vital role in slowing down Houthi advances by targeting heavy armored vehicles and reinforcements, government-aligned forces face a number of challenges. The coalition started gradually reducing logistical support for the national army last year and suspended some aid in March, a military official told the Sana’a Center.

Government forces have been forced to either go without adequate weapons or obtain them from the black market. A soldier fighting along the southern fronts in Marib told the Sana’a Center that when his unit was recently attacked by Houthi fighters in three armored vehicles, they only had AK47s to defend themselves. Compounding the situation, soldiers have not been paid their salaries for months, leading some to abandon the frontlines and cross into Saudi Arabia looking for work.

A shortage of competent military leaders in the army has become a crisis. In mid-September, Bin Aziz, the army’s chief of staff, sent his resignation to President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi but it was rejected, an informed source told the Sana’a Center. Most of the current commanders lack strategic planning skills as reflected in their focus on defensive operations in fronts surrounding Marib city. When troops are needed at other fronts, mobilization and deployment efforts have been far too slow.

Still, it does not appear that government forces and tribal fighters are prepared to surrender. Rather, most of them have taken the stance of General Mofareh Behaibah, a prominent Murad tribal leader and commander of the Bayhan axis, 26th Brigade and head of the Al-Jubah front. Behaibah, who has lost four sons fighting the Houthis during the past four years, said in a video that he would prefer to die than live in humiliation under Houthi rule. “We will defend ourselves (against the Houthis) until the last drop of blood.”

Ali al-Sakani is a Yemeni freelance journalist and researcher.

The Houthis’ Fatal Military Success

Commentary by Abdulghani Al-Iryani

Seven years into the Yemen war, nearly everyone has come to accept what was obvious from the start: foreign military interventions carry within them the seeds of their own failure. The arrogance of the intervening powers humiliates and demoralizes their local partners and clients. The intervening powers are often most comfortable dealing with the most compliant and easily manipulated of their local partners, thereby creating a selection process in which the least patriotic and the most corrupt often become the partners of choice. The arrogance of the intervening powers and the corruption of their local clients are frequently the two most powerful weapons in the arsenal of the parties resisting the intervention. This is the basic formula that has determined the outcomes of many foreign military interventions during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Most, observers and activists alike, now acknowledge that the Houthis are winning, but the question is what are they winning?

The Houthis’ most obvious victory is the division and discord of their opponents. Their military posture, bearing down on Marib and extending their reach into southern Yemen, is cause for celebration in Sana’a, Tehran, and capitals of the “Resistance”. Each military success for the Houthis strengthens their most radical and ideological faction at the expense of the moderates, both within the Houthi movement itself as well as in their larger coalition, which includes the reconstituted Sana’a-based elites of the former regime of the late Ali Abdullah Saleh, alongside tribal leaders from all over Yemen. The radical wing is ideologically committed to the Zaidi concept of Wilayah, restricting the right to rule for the descendants of Hasan and Hussein, grandsons of the Prophet Mohammed. Houthis continue to detain hundreds of members of the party Saleh had founded and led, the General People’s Congress, freeze the party’s assets and ban its activities, even internal party meetings. This harsh treatment of their key ally demonstrates that Houthis do not appreciate the fact that the northern Zaidi-tribal coalition led by Saleh was the instrument that turned their movement from a minor radical military militia into the closest approximation of a Yemeni state. That they can’t accept this indicates that they will not accept any meaningful power-sharing agreement with other actors in Yemen.

On a recent trip to Sana’a, I asked multiple Houthi interlocutors: “What will the role of the Sayyid (Abdelmalek al-Houthi) be in the post-war Yemeni state?” No one could give me an answer. As per Houthi dogma, Abdelmalek is considered Al-Wali Al-Alam, the premier holder of Wilayah who enjoys absolute power and authority over the nation. His power cannot be shared. At the moment, while the radical wing of the Houthis, intoxicated by a series of victories that were handed to them by the incompetent leadership of the other side, is planning to complete their control over the rest of Yemen, the desperate resistance in Marib is considering its options.

The tribes in Marib have a choice, the offer made to them by Houthis nearly a year ago: denounce the Saudi-led coalition, kick out Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and Islamic State militants in the governorate, and share oil and gas revenues from Marib with the Houthis. In exchange, the governor, Sultan al-Aradah, who hails from the prominent Abidah tribe, and the local leadership of Marib can keep their positions, and enjoy, at least for the time being, a degree of local autonomy. There is some attraction to the deal. The tribes in Marib have suffered significant losses in this bloody war of attrition. Some worry that the Houthis can simply stomach more casualties than the tribes. After all, the Houthis draw on a pool of recruits from a population of over 20 million. The tribes have a pool of less than a quarter of a million, and some are edging closer to accepting the Houthis’ deal.

The Islah party, which controls Marib for the anti-Houthi coalition, is in a tougher position. The Houthis found common cause with the Southern Transitional Council and its backer, the UAE, in annihilating Islah, often considered the Yemeni affiliate of the regional Muslim Brotherhood movement, while Saudi Arabia, the traditional backer of Islah, has turned hostile to Islamists. That leaves the leadership of Islah with few options.

While a few voices in the Marib leadership of Islah have responded favorably to a proposal to merge with the GPC to broaden its front and survive this exceptionally difficult time, the strategy of most in Islah’s leadership seems to be a tragic mixture of paralysis and defiance, all while discreet discussions between a faction of Islah and the Houthis are pointing toward a direct deal.

So, as Saudi Arabia waves the white flag and seeks a deal with the Houthis that satisfies its security concerns and, according to Saudi insiders, lets the Yemenis keep fighting, Islah is moving toward accepting the Houthis’ deal for Marib. This deal would likely lead to a more comprehensive agreement that would reproduce the pre-1962 theocracy, where the Sunni Islah becomes the junior partner of the Zaidi Houthis. Should that happen, it would produce a theocracy that offers no place for non-sectarian groups or southern Yemen. The Yemeni state would not survive that.

Nor will any deal between the Houthis and their opponents last. Excluded constituents will rise, and the Houthis will eventually find themselves fighting a number of different groups on multiple fronts, including the northern Zaidi demographic that has so far taken up arms to repel external “aggression.”

Whether Saudi Arabia and Houthis make a deal to end the war or Islah beats the Saudis to a deal with the Houthis first, any agreement that emerges will have little chance of survival in the long term. It will close one chapter of the Yemeni war only to open a new more violent one. All sides, the Houthis, Islah and the Saudis, should reconsider such paths of action and work together to achieve the minimum terms that will restore stability, and eventually an inclusive peace deal.

Political settlements that lead to a stable state are based on creating a balance among competing actors so that they check each other and make any resort to violence unprofitable. The broader the base of the political agreement, the more stable it becomes. In Yemen, the checks and balances of stable democracies don’t operate due to the lack of a tradition of rule of law and the absence of strong civil society. Non-inclusive elite deals may produce brief breaks in violence, but they can’t produce the long-term stability that Yemen needs for its survival.

Stability in Yemen can be achieved only through balancing the center with the periphery, ie, the governorates, through deep administrative, fiscal and security sector decentralization, using models tried and tested in federal systems around the world.

Houthi military successes are making them less likely to compromise on the principle of Wilayah and the absolute authority of the Sayyid, and therefore unable to share power in a way that creates these checks and balances. That could lead to the destruction of the Yemeni state. That is, in essence, what the Houthis are winning.

Abdulghani Al-Iryani is a senior researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies where he focuses on the peace process, conflict analysis and transformations of the Yemeni state.

This commentary was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies as part of the Leveraging Innovative Technology for Ceasefire Monitoring, Civilian Protection and Accountability in Yemen project. It is funded by the German Federal Government, the Government of Canada and the European Union.

The views expressed within this commentary are the personal views of the author(s) only. The contents can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the positions of partner(s), the German Federal Government, the Government of Canada or the European Union.

Southern Streets Erupts in Protest

STC, Yemeni Government Face Public Outrage

By Hashem Khaled

Thousands of people flooded streets of cities across southern Yemen in mid-September, protesting dire living conditions, the collapse of public services and an unprecedented drop in the value of the Yemeni rial (YR). Various levels of protests, strikes and general civil unrest were seen in the governorates of Taiz, Al-Dhalea, Lahj, Aden, Abyan, Shabwa, Hadramawt, and Al-Mahra.

The protests coincided with deepening tensions within the anti-Houthi coalition. Infighting between the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) and the Saudi-backed internationally recognized government of President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi has paralyzed the alliance and turned the south into a battleground even as the Houthis continue to advance on the governorates of Marib, Al-Bayda and Shabwa.

Aden Violence

The most violent protests occurred over three days, September 14-16, in the STC-controlled interim capital of Aden, where three protesters were killed and many others were injured.

Witnesses said STC forces used tear gas and opened fire with live ammunition to disperse crowds after angry protesters attempted to storm the STC headquarters in Crater district. Protesters also blocked major roads and threw stones at security forces in Crater and Khor Maksar district.

On September 15, in a bid to put down the protests, STC President Aiderous al-Zubaidi declared a state of emergency across all southern governorates during a televised speech in which he wore military fatigues.

STC spokesman Ali Abdullah al-Kathiri told Alghad Almushreq satellite TV network the state of emergency was a step to confront Houthi intentions to invade the south as the group seized territory in Shabwa. He also accused, once again, the Islah party within the Hadi government of working with the Houthis. “Any moves in southern regions are planned and coordinated by the Houthis and Islah,” Kathiri said. “The emergency decision came at a crucial moment to face such danger.”

However, some politicians and observers consider the STC announcement a tactic to try and clear the streets of protesters. “The state of emergency announcement by the STC leader aimed just to get out of the predicament it was facing as a result of the angry protests in Aden,” Yemeni journalist, Adel al-Hasani, who was released in March after six months of detention by STC forces, told the Sana’a Center.

Activists and media outlets loyal to Hadi and Islah cheered on the eruption of protests in Aden and other areas under control of the STC, accusing the UAE of replacing the legitimate state with what they call “mercenaries” that have undermined the rule of law in Aden.

“In January 2018 and August 2019, the STC declared war on the legitimate government and forced it out of Aden under the pretense of protecting peaceful demonstrators whom the legitimate government tried to suppress. Today, the STC suppresses those it claimed to protect yesterday,” former Prime Minister of South Yemen and first post-unification Prime Minister Haidar Abubakr al-Attas said on Twitter.

Mukalla Protests

Meanwhile, in Mukalla city, the capital of Hadramawt governorate, hundreds of protesters burned tires in the streets to protest electricity outages. They also demanded the stabilization of the Yemeni rial and called for the removal of Governor Faraj al-Bahsani. Al-Bahsani announced a partial curfew in all areas of the governorate in an attempt to quell the protests.

About 70 kilometers east of Mukalla in the coastal city of Al-Shihr, a 17-year-old protester was reportedly shot dead by security forces attempting to disperse protesters. Protesters in Al-Shihr chanted slogans calling for the withdrawal of the Saudi-led coalition and the downfall of the Hadi government, and tore down photos and billboards of Hadi and coalition leaders throughout the city.

“People are tired, they can’t afford fish, meat, or chicken. No salaries, no electricity and no services,” Salem Ahmed Bawazeer, a 36-year-old fisherman from Mukalla, told the Sana’a Center.

“We are tired of this situation as a result of the absent, corrupt Hadi government,” he said. “I call on the STC to come to Hadramawt and impose autonomy.”

Bahsani, whose authority is effectively limited to coastal Hadrawmat, is UAE-backed, but not aligned with the STC or their separatist aims.

Demonstrations in Wadi Hadramawt, Taiz and Shabwa

In Sayoun and Tarim, desert cities in the northern Wadi Hadramawt region, which is largely under the control of the Yemeni army’s First Military Zone, hundreds of protesters flooded the streets and blocked roads, criticizing the Saudi-backed Hadi government for the collapse of the economy. Local authorities announced a week-long curfew in an attempt to keep people in their homes, which involved closing schools and businesses.

“An egg costs YR150,” three times what it used to cost, said Mohammed Abdulkareem, a 33-year-old school teacher and father of two in Sayoun. “What is all this craziness? We are starving, poverty is killing our children, there are no services and no authority. What pushed us to the streets is hunger and no one has the right to stop us.”

Hadramawt is considered the wealthiest Yemeni region in terms of oil and gas resources. Although the local government is supposed to receive 20 percent of all locally-produced oil and gas revenue, people in Hadramawt wonder where that money goes in light of the absence of government services.

Protests also took place in Taiz on September 18 and 19, where demonstrators denounced the dire living conditions as well as the heavy handed tactics taken against the Aden protesters. In concert with these demonstrations, merchants in Taiz announced a partial strike to protest the collapsing currency. Further protests on September 27 saw one person killed and others injured when security forces opened fire to disperse the crowds.

Demonstrations also occurred in Shabwa governorate on September 15. The STC had called on its supporters to protest the arrest campaign and oppressive measures its membership had faced at the hands of the local authorities, or what the STC called the “Brotherhood Militia”. The local authorities said they would defend “security and tranquility” in Shabwa and likened the STC’s aims to that of the Houthis. In the end, while there were some arrests and intimidation of protesters, events in Shabwa appeared to have been relatively more peaceful than elsewhere.

Currency Collapse

Since early 2021, the value of the Yemeni rial has plummeted in areas under control of the internationally recognized government, reaching a record YR1,200 per $US1 in recent weeks. Before the war, the exchange rate was YR215 per US$1. (For economic details of the events, see ‘Collapsing Currency, Living Conditions Spur Widespread Protests in South Yemen‘).

Such a decline has had serious repercussions on living conditions and made basic foods prohibitively expensive for people in a country where two-thirds of the population don’t know where their next meal is coming from.

“The Aden branch of the Central Bank of Yemen continues to print new banknotes and keeps injecting them into the market without taking into account negative effects and rising inflation,” Ali Ahmed al-Twaiti, a Yemeni economic analyst, told the Sana’a Center.

“This is a problem for the government. The absence of authority is a big dilemma. When you look at the [decreased] volume of imports, you feel fear and anxiety, you believe that we are living without a state,” he said.

Others also blamed the Yemeni government’s foreign backers.

“The Arab coalition is directly responsible for the collapse of the currency, the deterioration of services and the suspension of [public sector] salaries. It must fulfil its legal obligations and return the situation to its pre-2015 state,” wrote Fathi Ben Lazerq, Yemeni journalist and Editor-in-Chief of Aden Al-Ghad news outlet.

“No one is to blame except the coalition. All others are just tools. The Saudi-led coalition is the only one responsible for all of the destruction and damage suffered by the Yemeni people, and it has to fix it,” said Lazerq.

Hashem Khaled is a Yemeni freelance journalist.

The South’s Hot Summer

Commentary by Hussam Radman

Over the past six years, citizens in South Yemen have become accustomed to the scorching temperatures during the summer that are accompanied by deteriorating services. The situation, however, dramatically worsened in September as protests demanding better services escalated at the same time as the Houthis made incursions into the south.

Southern governorates were supposed to witness a breakthrough during September after the governors of Aden, Al-Mahra and Hadramawt traveled to Riyadh, where they held intensive meetings with Yemeni Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed and Saudi ambassador to Yemen Mohammed al-Jaber. The purpose of these talks was to set clear mechanisms for the flow of local revenues into the government’s accounts, which will help cover some of the cost of a Saudi oil derivatives grant, a US$422 million deal announced in April to subsidize fuel for power plants in Yemen.

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia intensified its diplomatic efforts to revive the Riyadh Agreement, attempting to convince the Southern Transitional Council (STC) and President Hadi to reach an agreement for the Yemeni government’s return to the interim capital, Aden. According to Yemeni government officials, Saudi Arabia promised that the cabinet would return to Aden on September 15. As usual, however, that promise failed to materialize.

Increasing Protests

By the end of August, living conditions and the quality of services in Aden had deteriorated. Military personnel had not received wages for nearly a year. Power cuts reached 18 hours per day. The economic situation continued its freefall driven, in part, by a currency collapse. Fed up and frustrated, protesters took to the streets in mid-September in Aden, Shabwa and Mukalla, rallying against Hadi’s government, the STC and the Saudi-led coalition.

The STC quickly attempted to channel these protests for their own political purposes, calling on supporters to gather in Shabwa governorate to protest the policies of the Islah-affiliated local authority. In order to appear even-handed, the STC also allowed a margin of freedom for the calls to protest in Aden and initially directed its security forces to protect protesters and not to use violence against them.

In Shabwa, the STC-sponsored protests were met with force. Shabwa’s security committee, led by governor Mohammed bin Adio, instructed security forces to thwart the STC’s event and launched a wave of arrests targeting STC activists.

At the same time, protests in Mukalla were being put down by Hadramawt’s governor, Faraj al-Bahsani. While both the STC and local politicians loyal to Hadi’s government expressed support for the protesters, neither publically objected to the use of force against them, which resulted in the death of one and the injury of others.

In Aden, the protests also turned destructive as people blocked main roads and attacked public property. Unknown gunmen threw a hand grenade at a security patrol in Crater district; others exchanged gunfire with Security Belt forces in Al-Mansoura district. STC rivals, such as Islah, worked to exploit the wave of protests in order to weaken the STC and drag it into a violent confrontation with its popular incubator.

The Houthis Enter the Scene: Circumstantial Calm and Greater Complications

On September 15, STC president Aiderous al-Zubaidi declared a state of emergency in southern governorates and directed military forces to increase combat readiness to confront the Houthis’ expansion toward the governorates of Abyan and Shabwa. He also instructed security forces in Aden “to strike forces of terror and sabotage with an iron fist” and control the chaotic situation in Aden.

Many activists in Aden viewed Al-Zubaidi’s announcement as a preliminary step toward a wide campaign of oppression against the protests while officials in the STC said it was a necessary step in reaction to Houthi advances in Bayhan and Ain districts of northern Shabwa. The Houthis also launched intermittent attacks on northern Abyan from the border with Al-Bayda governorate.

The Houthi threat changed the behavior of the local political actors. The STC and President Hadi began exchanging positive messages about the importance of mutual cooperation against the Houthi advances.[1] The protests decreased and there appeared to be a consensus among all southern parties on the importance of suppressing demonstrations.

The popular protests and military confrontations combined to add momentum and urgency to calls for the government’s return to Aden, while at the same time frustrating Saudi mediation efforts. The growing Houthi military threat in Shabwa also distracted the attention of all local and regional actors away from calls for institutional and economic reform in Aden.

The Houthis halted their advance in northern Shabwa even though they have the capability to expand operations into other districts, including Merkhah al-Ulya and Merkhah al-Sufla along the Shabwa-Al-Bayda border, and potentially even threaten the governorate capital Ataq. Instead, the Houthis directed their war efforts toward Marib. If they seize control of Marib, capturing the government strongholds of Ataq, along with Sayoun in Hadramawt, will only be a matter of time.

If and when the frontline fighting with the Houthis reverts to a stalemate, the southern arena will go back to the same old dynamics: increased polarization between the STC on the one hand and President Hadi and Islah on the other; continuous economic collapse that nurtures waves of popular anger; and increasing violence and chaos due to the political exploitation of protests while security forces take evermore oppressive action against demonstrations under the excuse of the Houthi threat.

Saudi Arabia has tried to alter these dynamics by arranging with the United Arab Emirates for the return of Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek to Aden at the end of September. But his return did not coincide with any economic rescue plan. More importantly, the agreement was reached without President Hadi’s approval.

A new dynamic has entered the conflict in the south: the Houthi movement’s foothold in Shabwa and popular demonstrations against ruling authorities. This new dynamic threatens the two pre-existing major actors: the STC and the Hadi government, both of which exploit popular discontent to attack one another.

The only way to end this current cycle is through a coherent civil network to lead the protest movement toward a reform program and the development of a decisive international approach, led by the international quartet (Saudi Arabia, the UAE, US and UK) and the UN envoy to help implement the Riyadh Agreement and save the economic situation.

Hussam Radman is a journalist and Sana’a Center research fellow who focuses on southern Yemeni politics and militant Islamist groups. He tweets at @hu_rdman.

Education to Indoctrination Under the Houthis

How the Houthis Seized and Remade the Education System

Commentary By Salam Al-Harbi*

Like nearly every aspect of Yemeni society, the state of education in the country has suffered severely during the war. Schools systems have been weaponized as warring parties look to shape future generations, inculcating sectarian identities and political ideologies into impressionable minds. In Yemen today, schools aren’t oases of learning, but rather battlefields where a parallel war is being fought far from the frontlines.

Indeed, like Yemen’s competing central banks and much of its bureaucracy, there are two ministries of education. One based in Sana’a under the control of the Houthis, and another in Aden as part of the internationally recognized government. Each ministry is focused on shaping the identities of students in ways that will continue to exacerbate tensions in Yemen. No longer is there a single curriculum, a shared vision of the state or even a unifying national identity. Instead, there is division, mistrust and hatred that is being passed down from one generation to another.

In Houthi-controlled territory, students, teachers and administrative employees have been subjected to an intensive identity change. Some of this has been aided by Yemen’s poor economic situation and currency crisis, which saw the Central Bank of Yemen essentially run out of money and halt salary payments to most civil servants in 2016, including teachers. In the years since, while teachers working in areas nominally controlled by the Yemeni government regained some income stability, those in Houthi-controlled areas have been largely without their state salary. Without salaries, many teachers were forced to look for alternative employment, and some ended up joining armed groups in an attempt to provide for their families.

Students faced similar difficulties, as many families could no longer afford to send them to school and the teacher shortage meant that many schools were no longer fully staffed. A report from Mwatana for Human Rights, released earlier this year, estimated that 81 percent of all students in Yemen missed significant portions of the school year due to the fighting and more than 53 percent missed at least a whole year of school.

As they have done in most state institutions, the Houthis replaced much of the leadership within the Ministry of Education. In 2016, Yahya al-Houthi, the half-brother of movement leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi, was appointed Minister of Education. His deputy and undersecretary are both prominent Houthis who hail from the group’s heartland in Sa’ada governorate, while education directors in Houthi-controlled governorates and districts are almost exclusively Hashemites who belong to the Houthi movement. While the Houthis have seized almost full control of the education sector by appointing their members throughout the state apparatus, these appointees effectively operate within a parallel hierarchy to both the central Houthi chain of command and the state bureaucracy. Yahya al-Houthis’ deputy, Qassem al-Hamran, for instance, is at the helm of shaping education policy in northern areas, even while the former is technically both Minister of Education and the brother of the ultimate leader of the armed Houthi movement, Abdelmalik al-Houthi. Al-Hamran is also the acting head of the Houthi movement’s executive office, which has departments that work parallel to the Ministry of Education and other governmental institutions.

The Houthis systematically removed members of the Islah party from positions within the ministry in 2015 and later, following the death of former president Ali Abullah Saleh in 2017, did the same to most members of Saleh’s General People’s Congress (GPC) party. In order to ensure the loyalty of all remaining teachers and ministry staff, the Houthis have required each individual to participate in so-called “cultural courses”, which are designed to propagate Houthi ideology.

The Houthis have also made changes to school curriculum as well as to school holidays, instituting 16 different political and religious celebrations,[2] including Ashura, a Shia holiday never previously commemorated in Yemen, even under the Zaidi imams.

School directors in each district meet every Wednesday to listen to a lecture either by Abdelmalek or his late brother Hussein, the movement’s founder, in dedicated halls. Attendance is taken, according to one director who spoke to the Sana’a Center on the condition of anonymity; attendees are aware that they are being evaluated. According to an official who administers tests in Sana’a, the Houthis also give high grades to high school students who fight on the frontline regardless of whether or not they attend classes.

The Houthis also impose strict supervision on private education, which has become increasingly popular as the quality of public education has deteriorated. Foreign private schools in Sana’a, such as the American school, have been closed since 2015, and the Houthis have stopped issuing licenses to new schools. The parliament in Sana’a is currently discussing a new law that would only allow countries that have cultural exchange agreements with the Houthi authorities to open private schools in Houthi controlled territory. Currently, only Iran and Syria have cultural exchange programs and recognize the Houthis as a government. This law parliament is currently debating states that the Houthis can cancel the license of any school that spreads “principles and ideas which contradict Islamic Sharia and the values and morals of the Yemeni people.”

Hussein Hazeb, a tribal sheikh and member of the GPC, is the minister of higher education in the Houthi government. But his deputy and undersecretaries, who set the ministry’s policies, are all Houthi members. Among the changes the Houthis have made are imposing mandatory courses on the Arab-Israeli conflict and national culture for all university students. Many of these are taught by Houthi members, who are not faculty members and do not have the degrees required to teach.

Since seizing Sana’a in September 2014, the Houthis have appointed three loyalists as directors at the University of Sana’a. The directors soon imposed strict policies that prohibited male and female students from mingling on campus. University security guards were under order to suspend any male student who spoke to a female classmate. At the same time, salaries of university professors, much like other employees on the public payroll, were suspended and, in 2018, the Houthis laid off over 100 professors. Masters theses and doctoral dissertations must now go through a special committee appointed by the movement to edit the content based on the movement’s vision. Houthi security forces have raided schools and universities in Sana’a and elsewhere that did not adhere to the new regulations.

The Houthis have imposed similar restraints on private universities. For instance, the director of the University of Science and Technology in Sana’a was arrested in early 2020 and replaced by a Houthi loyalist. The internationally-recognized government responded by electing not to recognize the university’s degrees.

The Houthis have changed the names of university halls to commemorate the movement’s symbols. They prohibit mixed graduation ceremonies and banned photos of male and female graduates together. A percentage of each faculty is now allocated to the children of Houthi members who were killed fighting in the war. Those students are exempted from all fees.

The Houthi approach to education aims to mold the social and national identity of children to the group’s sectarian ideology and political ends, at the expense of actual knowledge and skills acquisition. This represents a long-term threat to peaceful social co-existence in Yemen, with the potential to give rise to new generations of students who view diversity, difference, critical thinking and indeed knowledge and science as things to be feared and attacked. This sort of ‘education’ threatens the country’s stability by planting the seeds for future conflicts. It also robs Yemen of the skill sets its people need to rebuild and develop the country. The war presently tearing the country apart, creating such suffering for Yemenis and sending children to the frontlines, is already horrific; Houthi efforts to condemn Yemen’s children to such a future and much worse is truly abhorrent, and must be resisted however possible.

*Salam Al-Harbi is a pseudonym for a resident of Sana’a whose true identity is being withheld for security reasons.

Curriculum Changes to Mold the Jihadis of Tomorrow

By Manal Ghanem*

Since its takeover of Sana’a in 2014, the armed Houthi movement has cemented its hold over northern Yemen. An important part of this has been its extensive focus on education, systematically targeting the youth with Houthi ideology. This has meant moving from a civic education to one with a more religious point of view – a move similar to that made after the Iranian Revolution in 1979, when Ayatollah Khomeini’s followers changed school curriculums in Iran as a way of shaping the next generation.

In Yemen, courage is easily linked to martyrdom. Stories of brave men defending their country have been the backbone of folktales in the culture for centuries. The concept can be easily manipulated to depict bravery as an effort to defend the homeland against an enemy. Today, after seven years of conflict, a revised integration of this concept is seeping into the minds of children. The stories are no longer of heroes in farfetched scenarios; they are now real examples of their fathers, brothers and cousins. The Houthi movement is molding future generations of fighters.

Where it all Began

Since coming to power, the Houthi authorities have implemented a sectarian agenda to ensure the loyalty of children in the future and persuade adults to fight on the frontlines today.[3] In education, after more than seven years of rule, the changes that have been made to the school curricula and in the education system more broadly are easy to see. Examples include what might appear to be small changes in how a Quranic verse is interpreted, but these changes completely alter one’s understanding of the text. For instance, verses that glorify jihad have been highlighted, while other verses have been reinterpreted to align with the group’s identity. Hashemites are portrayed as superior, while whole chapters that once illustrated the diverse and rich history of Yemen have been replaced with chapters that focus on Zaidi, Shia and Houthi leaders. Stories about historical Arab heroes – such as Omar ibn Abdul Aziz, Omar al-Mukhtar, and Youssef al-Azma, for example – have been replaced by those about Saleh al-Sammad, the former Houthi president, who was killed in April 2018.[4]

Changes started in Sa’dah, where the group integrated their literature through distributing writings by the group’s founder, Hussein Badr al-Deen al-Houthi.[5] The teachings of Al-Houthi became the main curriculum in the governorate in 2010. The group’s educational approach stems from their conviction that the current educational system corrupts the youth.[6] As a means to fight back, the Believing Youth Movement came together in the early 1990s, establishing religious centers to teach Islamic sciences according to Zaidi views, with the Houthi movement subsequently arising from within these efforts.[7] Since 2010, Al-Sarkhah, the official Houthi slogan, has been enforced in all schools in the governorate, replacing the national anthem in many cases.[8]

In 2016, two years after the Houthis took control of Sana’a, the group appointed Yahya Badr al-Deen al-Houthi, the brother of current Houthi movement leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi, as the Minister of Education. The move sparked fears in Sana’a and other governorates under the group’s control about the possibility of changing or modifying educational curricula.

Initially the changes were slight, but for the 2021/2022 school year, the Ministry of Education in Sana’a issued a modified curriculum in Islamic studies, the Holy Quran and social studies for primary school. These introduced new lessons and modified or deleted original lessons covering civic rights, the role of women and the history of influential figures that shaped the history of Yemen.

The Houthis have also instituted changes at technical, vocational and community colleges, all under the broad pretext of “protecting the faith”. As part of this process, the Houthis have monitored what professors teach in the classroom as well as the political views of those professors and teachers.[9]

The Process of Change

For the Houthi movement’s ideas and beliefs to be instilled among school students – and changes in the curricula to be realized smoothly – the group has been prepared to change and remove school principals from their jobs, replacing them with Houthi loyalists. According to Yahya al-Yinai, a spokesperson for the Yemen Teachers Syndicate – a group loyal to the internationally-recognized government – these tactics have now left the Houthis in control of 90 percent of the schools in the northern highlands.[10]

To fund the printing and distribution of the new curricula, the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Sana’a has imposed fees on students at public schools as ‘community contributions’ (elementary students pay 500 Yemeni rials (YR) and secondary school students pay between YR1000-YR1500 monthly). It has also raised the fee for the renewal of private school licenses. It has also forced private schools to purchase the new curricula and donate copies to nearby public schools. The MOE’s Education Office in Sana’a also conducts random inspections of schools to ensure that the new curriculum is being used.[11] Schools found using the old curriculum face fines of up to YR400,000.[12]