Algharbi Al-aala village perched on the edge of a cliff in western Mahweet governorate, pictured June 25, 2019 // Photo Credit: Asem Alposi

The Sana’a Center Editorial

War by Remote Control

The Yemen conflict is quickly becoming a model for how a non-state actor can effectively employ unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones, as a force equalizer in 21st-century wars.

Particularly in 2019, Houthi forces’ deployment of explosive-laden drones on long-range kamikaze missions has allowed them to continually extract costs from their adversaries far beyond the frontlines. In January, a Houthi spokesperson declared this the “Year of the Drones” just after Houthi forces flew a UAV into a military parade at Al-Anad air base in Lahj governorate killing, among others, the Yemeni government’s military intelligence chief and the army’s deputy chief of staff. Houthi UAV attacks this year have also regularly targeted civilian airports and military bases in southern Saudi Arabia, with Saudi authorities confirming almost 50 injured and one killed in attacks on Abha airport alone in June. This is even with Saudi and Emirati air defenses taking out many drones before they reach their target.

Guerilla tactics against a superior military force have long emphasized political impact over military effectiveness. The Houthi use of drones is a modern twist on asymmetric warfare, with the advantages of being able to reach deep into a rival’s territory and hit a specific target without incurring casualties and at relatively low cost. While various insurgent groups have sought to utilize drones similarly, the Houthis appear to be the first to have mass deployed them on the cheap as precision-guided weapons.

Yemen is no stranger to drones; the United States carried out its first extra-judicial killing of a suspected Al-Qaeda member in the country using a drone-fired missile in 2002. In almost two decades since, American drones have increasingly prowled above Yemen to strike suspected terrorists below. The times when these drones also bombed civilians in their homes, at weddings and at funerals have almost mythologized them in many communities as death brought from the sky. Both the Houthis, in their attacks on Saudi civilians, and the Saudis, in their airstrikes on civilian targets in Yemen, are following the American legacy of impunity in this regard.

US drones, however, are no longer beyond reach. In early June a Houthi-fired missile took down an American MQ-9 Reaper drone over Hudaydah governorate. In an unrelated incident later in the month, the Houthis’ regional patron, Iran, shot down a US surveillance drone over the Strait of Hormuz. Amid already heightened US-Iran tensions, the incident almost sparked open conflict between the countries. Had it been a conventional manned aircraft and had a US serviceman been killed or captured, Washington would likely have responded aggressively. However, that the UAV was a piece of machinery – albeit worth US$130 million – allowed President Donald Trump to talk tough but back down from actually carrying out strikes on Iran.

The United States pioneered UAVs and through the 2000s had a near monopoly on weaponized drone technology. In wanting to maintain operational flexibility in places like Yemen, however, it failed to push for international norms regarding drones in conflict zones before their use had already become widespread. This valuing of short-term gain over long-term strategic interest appears to be coming back to haunt the United States and its allies in the region. Now, armies around the world are deploying drone technology, including Iran; the Houthis’ own UAVs mimic Iranian models, according to the UN’s panel of experts on Yemen.

The Yemen conflict, with its expanding use of drones and attempted measures to counter them, should be seen as a harbinger of the decreasing leverage of conventional military superiority in wars by remote control.

Contents

Developments in Yemen

- Yemen’s Drone Wars

- Military and Security Developments

- Political Developments

- Economic Developments

- Humanitarian Developments

International Developments

- Western Countries’ Arms Sales to Riyadh Face Increasing Scrutiny

- At the United Nations

- In the United States

Children from Yemen’s Muhamasheen community in the city of Rada’a, Al-Bayda governorate, pictured June 8, 2019 // Photo Credit: Marwan al-Juraidy

Children from Yemen’s Muhamasheen community in the city of Rada’a, Al-Bayda governorate, pictured June 8, 2019 // Photo Credit: Marwan al-Juraidy

Developments in Yemen

Yemen’s Drone Wars

Downed Drone Escalates US and Iran Tensions, Yemen “Key” Battleground

June saw rising tension between Tehran and Washington, as the sides came close to an open conflict over a downed American drone. US President Donald Trump said he called off strikes on Iran on June 20, minutes before they were due to be launched. The strikes were threatened in retaliation to the June 20 downing of a US surveillance drone over the Strait of Hormuz by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard.[1] Tehran said the US$130 million drone had violated Iranian airspace, while Washington said it was an “unprovoked attack.”[2] Trump tweeted on June 21 that he had called off the strikes after learning that they could kill 150 people.[3]

Prior to the downing of the drone, the US had blamed Iran for attacks on two oil tankers in the Gulf of Oman, near the Strait of Hormuz, on June 13; Iran denied the accusations.[4] CENTCOM said an Iranian surface-to-air missile attempted to shoot down a US drone that had been deployed to the area for surveillance on the same day.[5] On June 18, Washington announced that 1,000 additional US forces would be sent to the region.[6]

Adding to the tension in the Gulf in June, an increase in Houthi attacks on targets in Saudi Arabia heightened hostility between Riyadh and Tehran (see ‘Houthi Forces Strikes Saudi Airports’). The United States, Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom contend that the Houthi attacks rely on Iranian weapons and technology.[7]

On June 28 US special envoy on Iran, Brian Hook, said the fight against the Houthis in Yemen was a key front in the crisis with Iran.[8] “If we do not prevent Iranians from laying down deep roots in Yemen, they will be in a position to threaten to close the Strait of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandab,” Hook said, adding that the US was “pushing back on Iran’s long game in Yemen.”

The United States imposed new sanctions against Iranian leaders on June 24, while Tehran reiterated that it would not comply with its commitments under the nuclear deal in the absence of relief from US sanctions promised in the 2015 agreement.[9] On July 1, Iran exceeded the nuclear deal’s 300kg limit on stockpiled low-enriched uranium, breaching the agreement for the first time, after failed efforts by European leaders to prevent any violation of the deal by Tehran.[10] President Trump pulled out of the deal in May 2018.

Houthis Claim Drone Attacks on Saudi Airports

A Houthi attack on a Saudi airport on June 23 killed one civilian and injured 21 more, Saudi state media reported.[11] Coalition spokesperson Colonel Turki al-Maliki did not specify the weapon used in the attack on Abha airport in southern Saudi Arabia – around 110 kilometers from the Saudi-Yemeni border. The Houthis said they had targeted Abha and Jizan airports with Qasef-2K drones that day.[12] An attack on Abha airport on June 12 injured 26 civilians, according to Saudi state media.[13]

The Houthis claimed successful attacks on Abha and Jizan airports and Khalid Air Base throughout June, though most of those acknowledged by the coalition were said to have been intercepted. The coalition said a Houthi projectile landed near a desalination plant in Al-Suqaiq on Jizan’s coast on June 19, causing no damage.[14] The Houthis said they had launched a cruise missile at the plant that had hit its target.[15]

There has been a marked increase in Houthi-directed attacks within Saudi Arabia in recent months. In May, the Houthis announced a new campaign against 300 military targets in Saudi Arabia and the UAE in response to what they called the coalition’s spurning of peace efforts.[16] The Houthis also claimed successful strikes within Yemen. On June 3, Houthi media said a combat drone hit a military parade at the Ras Abas military camp in Aden, though the Saudi-led coalition said it intercepted the aircraft west of the interim capital.[17] On the same day, Houthi forces said they had launched a missile at Al-Hadabeh camp in Az-Zahir district, southern al-Bayda governorate.

Meanwhile, Houthi spokesperson Yahya Sarea said Houthi forces downed a US drone in Hudaydah governorate on June 6, which was followed by reporting on the incident in pro-Houthi media outlets in the days following.[18] United States Central Command (CENTCOM) later confirmed Houthi forces had shot down an American MQ-9 Reaper drone.[19] CENTCOM said a Houthi surface-to-air missile was used to hit the drone, which it called an “observation aircraft,” and that the capabilities shown in the operation indicated Iranian assistance.

US Officials: Drone Attack on Saudi Pipeline in May Originated from Iraq

On June 28, the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) reported that a drone attack on a Saudi pipeline in May was launched from Iraq, not Yemen, citing unnamed US officials who had investigated the incident.[20] [21] Houthi forces said at the time that they had conducted the May 14 operation, which hit Saudi Arabia’s East-West Pipeline, resulting in a temporary closure but minimal material damage.

Saudi Arabia blamed the armed Houthi movement for the attack, saying it was ordered and facilitated by Iran. The WSJ report cited the US officials as saying the drone attack was “more sophisticated” than previous Houthi-claimed attacks in Saudi Arabia, deploying different types of drones and explosives, and that Iran-backed Iraqi militias were likely involved. The distance of the attack from the Saudi-Yemen border, coupled with known Houthi drone capabilities, had already put the movement’s culpability for the May attack in question.

The WSJ, citing expert opinion, said while air defenses in Saudi have already established countermeasures to defend against drone attacks from Yemen in the south, there are no such defenses prepared for drone attacks originating from over the Iraqi border in the north. Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi denied the pipeline attack originated from Iraq.

Military and Security Developments

UAE Withdrawing Military Assets and Personnel from Yemen

In June, Sana’a Center sources among the anti-Houthi forces in the Red Sea city of Mokha reported that the UAE was undertaking a large-scale removal of its military assets and personnel. These included armoured vehicles, tanks, radar installations, helicopters and everything “important or heavy,” according to one source. This has left frontline anti-Houthi ground forces along the west coast without air support from UAE attack helicopters for the first time since they began advancing up the coast in early 2017. Local news outlets also reported on June 22 the departure of soldiers and military hardware via the oil port in Aden’s Al-Buraiqa district.[22]

As of the beginning of July, the Washington Institute, citing UAE sources, reported that Emirati forces were 100 percent withdrawn from Marib governorate, 80 percent from Hudaydah governorate, had begun to draw down in Aden, and had reduced staff at a forward operating base in Eritrea by 75 percent.[23] The December 2018 Stockholm Agreement, reached between the Yemeni government and the armed Houthi movement, had redirected the coalition’s military efforts in Hudaydah onto the negotiations track, according to the institute, creating a window for the UAE – fatigued by the war and wishing to avoid a quagmire – to exit Yemen. Emirati officials, speaking to Reuters, appeared to concur with this assessment, saying that it was a “natural progression” for the ceasefire in Hudaydah – part of the Stockholm Agreement – to bring about a negotiated end to the war.[24] The same Emirati official, however, said the “troop movements” did not constitute a withdrawal from Yemen. Several western diplomatic sources characterized the UAE’s military drawdown as a redeployment of forces home in the face of rising regional tensions with Iran.

The UAE has established a heavy military presence in Yemen’s southern governorates and on the Red Sea coast since it entered the conflict as part of the Saudi-led coalition. It spearheaded a counterterrorism campaign in the first years of the current conflict, at a time when Al-Qaeda in the Arabia Peninsula (AQAP) held swathes of territory in the south — including the port city of Mukalla in Hadramawt governorate. Despite the current military drawdown, the UAE is expected to maintain its counterterrorism forces in Yemen.[25] The UAE has also provided financial and military backing for pro-separatist armed groups and spearheaded the offensive up Yemen’s western coast to Hudaydah.

Fighting Between Anti-Houthi Forces in Various Southern Governorates

Tensions between coalition-backed groups and other anti-Houthi actors escalated in southern Yemen in June, resulting in armed violence in some cases.

Fighting broke out in Shabwa governorate between a Yemeni army unit and UAE-backed forces. According to Sana’a Center sources in southern Yemen, as well as local news outlets, on June 19 clashes occurred in the city of Ataq between the government’s 21st Brigade and the UAE-backed Shabwa Elite Forces. Tensions were heightened by the Shabwa Elite Forces’ arrival days earlier and their establishment of military checkpoints in an area dominated by the Yemeni army’s Third Military Region units. A de-escalation committee was formed to resolve the conflict, but an agreement had not materialized as of this writing. The hostilities in Ataq were foreshadowed by clashes near an oil well in Shabwa’s Al-Marwahah area on June 16 between UAE-backed southern separatist fighters and the 21st Yemeni Army Brigade.[26]

There have been previous instances of armed clashes between the Shabwa Elite and the Yemeni army, often sparked by unofficial checkpoints. As with other southern governorates, UAE-backed southern separatist forces dominate along the coast in Shabwa, with the Third Military Region controlling inland areas. Separatist groups portray the Third Military Region forces as a northern military presence in their would-be independent southern state. Competition between these groups is partly driven by economic interests given the lucrative oil production and distribution in the area. Ataq City is also located on a strategic crossroads linking two main east-west roads.

Tensions flared again in Socotra governorate between UAE-backed groups and those who oppose Emirati presence on the island, which lies off Yemen’s southeastern coast. Local media reported that an unidentified UAE-backed pro-Southern Transitional Council group blocked a convoy transporting the Minister of Fisheries Fahd Kafayen and the Governor of Socotra Ramzi Mahrous on June 18.[27] A statement issued by local authorities the following day said armed forces describing themselves as belonging to the UAE-backed Security Belt attacked Socotra port and clashed with the local Coast Guard.[28] According to local media, Socotra’s local security forces had prevented the offloading of a UAE-leased vessel containing military hardware and vehicles.[29] There were both anti-UAE and pro-STC protests in the days following, though no further reported violent incidents.[30]

Confrontations in Socotra have largely been avoided since the UAE deployed troops and weapons to the island in May 2018, which prompted criticism from the Yemeni government and an international backlash. In response, the UAE withdrew soon after. Abu Dhabi has deepened its footprint in Socotra in recent years, despite the island being largely isolated from the Houthi-Yemeni government conflict. Emirati-funded development and infrastructure projects (some going back decades) have support among the population, but there are concerns over long-term intentions given Socotra’s potential as an addition to the UAE’s growing portfolio of maritime facilities around the Yemeni coastline and Horn of Africa.[31] The UAE denies allegations it intends to establish de facto control of the island, saying it recognizes Yemeni sovereignty and is there for humanitarian purposes.

There are similar fears in Yemen’s Al-Mahra, centered on Saudi Arabia’s objectives in the eastern governorate. In June, local news outlets reported the coalition had dispatched an Apache helicopter after tribesmen blocked a pro-Saudi military convoy. Al-Masdar reported that the convoy was traveling from the coalition’s Khalidiya camp in Hadramawt governorate on June 3 when tribesmen intercepted them in Al-Mahra’s Shahin district.[32] Tribal sources said the helicopter fired at the area around the incident, without causing any casualties. Protests and sit-ins against the coalition military presence have become commonplace in Al-Mahra, where Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Oman seek leverage by backing prominent tribesmen with weapons, funds and the granting of citizenship. (For further details, see the Sana’a Center’s recent paper: Yemen’s Al-Mahra: From Isolation to the Eye of a Geopolitical Storm.)

Saudi Special Forces Capture Local Daesh Leader

On June 3, 2019 Saudi Special Forces, backed by US Special Operations, raided a house in Al-Ghaydah, the capital of Al-Mahra, Yemen’s eastern-most governorate.[33] The raid, which reportedly lasted only 10 minutes, netted the head of the so-called Islamic State group, or Daesh, in Yemen, Abu Osama al-Muhajir, as well as a number of other suspects, including the group’s financial chief.[34] According to a Saudi statement, there were also three women and three children in the home at the time of the raid.[35] There were no casualties, according to the Saudis.

Al-Muhajir, whose real name is Muhammad Qanan al-Sayari and is also known as Abu Sulayman al-Adani, has been under US sanctions since October 2017.[36] He has been the head of Daesh in Yemen since March 2017.

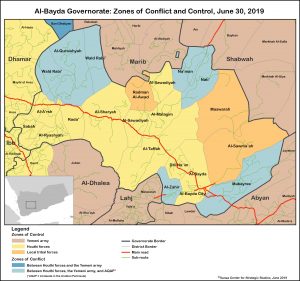

Perhaps the most surprising thing about al-Muhajir’s arrest is where it took place. In Yemen, Daesh has been most active in Al-Bayda and remote areas of Hadramawt governorate, where for the past year it has been involved in a tit-for-tat guerilla war with AQAP militants. Al-Muhajir was arrested nowhere near those frontlines. Instead, he was over 600 miles away, near Yemen’s border with Oman. Saudi Arabia only announced Al-Muhajir’s capture on June 25, which may have been a result of wanting to get as much actionable intelligence as possible before Daesh realized Al-Muhajir had been compromised.

Al-Muhajir’s capture comes at a difficult time for Daesh. Although the group continued to carry out sniper attacks and raids against AQAP throughout June, it is clearly losing the intra-jihadi fight. Daesh’s numbers are down, its brand is tarnished, and AQAP is showing signs of moving on to different targets.

On June 4, AQAP released a short statement to the “Muslims living in Shabwa,” warning them it was about to start attacking the Shabwa Elite Forces, a UAE proxy force.[37] “Do not congregate near them, ride in their vehicles or gather around their camps,” the statement said. Since then, AQAP has carried out a number of attacks against the group. Experts who track AQAP’s attack claims have pointed out that this is the first time AQAP has targeted the Shabwa Elite Forces in three months.[38]

On June 25, a suspected US drone strike in al-Bayda governorate killed five members of AQAP, including Al-Khadhr al-Tayyabi, an AQAP commander in Tayyab district.[39] The United States has not publicly claimed the strike.

Political Developments

Yemen’s Foreign Minister Steps Down After a Year in the Role

Khaled al-Yamani, foreign minister for the internationally recognized Yemeni government, resigned June 10 after holding the position for just over a year, Al Arabiya reported.[40]

A government official, who spoke to the Sana’a Center on condition of anonymity, said Al-Yamani had grown frustrated at the presidential office’s interference in his ministry. According to the official Al-Yamani felt that the president’s office was relegating him to a largely symbolic figure by controlling decisions within his ministry, such as directly appointing foreign ministry officials, while in other cases refusing to allow ambassadorial vacancies to be filled. Financial and administrative decisions at the foreign ministry have also been controlled by a Hadi-appointed deputy minister, who reports directly to the president rather than the foreign minister. The official said Al-Yamani also felt he was being made a scapegoat for the tensions between the UN special envoy and President Hadi.

Hadi accepted Al-Yamani’s resignation on June 17 — an unusually protracted lag. The president has not yet named a replacement, who will be the fourth foreign minister in as many years.

President Hadi Travels to the US for Medical Reasons

President Hadi left for the US on June 16 for routine medical tests.[41] Hadi is known to have a heart condition and receives regular check-ups and treatment at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. Concerns were raised over the president’s health in August 2018 when he collapsed in Cairo just before he was due to give a speech. During the latter half of 2018, Hadi visited the Cleveland Clinic with greater frequency for tests and unspecified medical treatment, local news outlets reported at the time.

Economic Developments

Economic Committee Bans Oil Imports from Oman, UAE and Iraq Ports

On June 21, the Yemeni government’s Economic Committee issued a circular stating that, effective immediately, the committee will not approve any fuel shipments arriving from Al-Hamriya Port in Sharjah, UAE, or any port in Iraq or Oman.[42] The Economic Committee also stipulated that importers must provide a certificate of origin from an official and impartial entity, accompanied by an official permit application form.[43] The Economic Committee characterized these conditions as an extension of Decree 75, issued in October 2018.[44]

The Economic Committee said the new conditions were part of its ongoing efforts to prevent “illegal fuel trade” and curb “fraudulent specifications” on fuel import applications. The blanket ban on Omani and Iraqi ports is a notable attempt to reduce the import of Iranian fuel. A key objective of Decree 75 was to prevent Houthi-linked importers from importing cheap Iranian fuel which could be sold on the local market for a huge mark up. It also sought to cut off Iranian fuel financing whereby direct financial assistance was reportedly being provided to the importer (and by extension to Houthi affiliates) through money exchange companies.[45]

Sana’a Center interviews with various officials working in the fuel import industry – including importers and brokers – as well as available vessel tracking information, suggest that Iranian fuel has continued to be imported in Yemen since Decree 75 was enacted, via Oman and to a lesser extent Iraq, albeit at a reduced rate. Various assessments since the introduction of Decree 75 – by the Economic Committee, the Aden central bank, and others – have indicated that the amount of Iranian fuel being imported via the United Arab Emirates has decreased.

Yemeni Government Attempts to Establish Monopoly Over Fuel Imports

On June 25 2019, the Economic Committee announced that the Yemeni government’s cabinet had unanimously approved the decision to designate the Aden Refinery Company (ARC) as the sole authority in Yemen permitted to import fuel.[46] Yemeni government officials, speaking to the Sana’a Center, said all ARC fuel shipments will initially be sent to Aden port. ARC will then allow the Yemen Petroleum Company (YPC) and private sector fuel traders to purchase fuel from the ARC in Yemeni rials; in turn, they will be able to distribute and sell fuel on the domestic market. The cabinet did not specify if the Yemeni government planned to arrange for fuel deliveries to other ports around Yemen, such as Hudaydah and Mukalla. The alternative would be the more costly and problematic option of overland transportation, which would be profitable for those fuel traders with sizeable fleets of fuel transportation trucks.

The new arrangement has the potential to significantly benefit billionaire businessman Ahmed Saleh al-Essi, given his known influence over the ARC and with senior Yemeni government officials, including President Hadi and his sons.[47] Al-Essi’s marine transport company would also be a prime candidate for contracts to transport fuel from Aden to other ports in Yemen.

Sana’a Center sources said the Yemeni government may look to set a unified price for domestic fuel sales, although it does not have any control over fuel prices in Houthi-controlled areas, where roughly two-thirds of the country’s population resides. Given the larger customer base in areas they control, Houthi authorities have used taxes and other fees on fuel sales to garner revenue. As of this writing, Houthi authorities have not responded to the Yemeni government’s new terms for importing fuel, but it is likely they will attempt countermeasures.

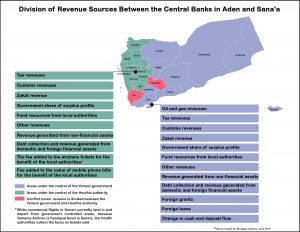

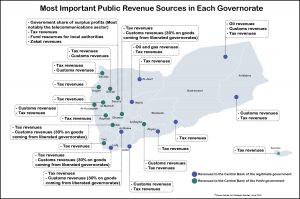

Central Bank’s Marib Branch Connected to Aden HQ

On June 15, the central bank branch in Marib governorate was connected to the central bank in Aden, the Economic Committee announced.[48] The central bank branch in Marib had been operating independently since August 2015, when the governor disconnected the local branch from the then-headquarters of the central bank in Sana’a. President Hadi ordered the relocation of the Central Bank of Yemen headquarters from Sana’a to Aden in September 2016.[49] The Marib branch was not reconnected, however, and thus local revenues, including those generated from oil and gas sales, were not transferred to the central authorities but remained in Marib.[50]

Several Sana’a Center sources have said there is an account at the Marib central bank branch – funded mainly from deposits made by the state-run SAFER Exploration & Production Operation Company’s oil and gas operations – controlled directly by the Yemeni president and his vice president. Notably, there were special arrangements made such that this is the only account at the Marib central bank that will not fall under the purview, or scrutiny, of the Aden central bank despite the new connection.

The connection of the central bank branch in Marib followed an agreement-in-principle reached May 31 between Central Bank Governor Hafedh Mayad and Governor of Marib Sultan al-Aradah during a meeting in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, which was also attended by the manager of the Central Bank branch of Marib, Jamal Qaid al-Kamal.[51]

Prior to implementation on June 15, Mayad appeared to grow frustrated with the pace of developments following the agreement reached in Jeddah. In a June 7 statement, Mayad expressed his dissatisfaction that not all locally generated revenues in Marib and Al-Mahra governorates were being transferred to the central bank in Aden.[52] Although the central bank branch in Al-Mahra has reconnected to Aden and is transferring some locally generated revenues, it is not transferring customs revenues from Nishtun port or from the Shahin and Sarfait land border crossings with Oman.

Yemeni Money Exchange Companies Launch 24-Hour Strike as Frustration Deepens

The Yemeni Exchangers Association announced a strike by its members in Sana’a on June 19.[53] The strike was suspended after 24 hours at the request of UN agencies and humanitarian organizations. The Yemeni Exchangers Association and the Yemen Banks Association (YBA) announced in a joint statement on June 20 that the strike would be suspended until June 30.[54] Both organizations said they would give the central banks in Aden and Sana’a time to reconsider their respective policies regarding the regulation of Yemeni money exchange companies.[55]

Money exchangers have said they are frustrated with the contradictory regulations imposed by Aden and Sana’a, in particular competing requirements to get an operating license from both central banks. The official window for submitting applications for license renewal closed, in both Sana’a and Aden, at the end of March 2019.

According to officials working in the banking sector who spoke with the Sana’a Center, the driving force behind the recent strike was the central bank in Aden’s requirement that money exchange companies submit detailed financial reports – a demand that has met strong resistance from authorities in Sana’a.[56] The central bank in Aden is asking money exchange companies to provide a breakdown of their financial transactions, including who their clients are and details of all inbound and outbound money transfers. Meanwhile, the Houthis are threatening to close down any Sana’a-based money exchange company found to have sent financial reports to Aden.

Sources at the central bank in Aden told the Sana’a Center that the new policies aim to curb currency speculation, money laundering and terrorism financing. The central bank in Aden warned two money exchange companies – Swaid & Sons Exchange Company and Al-Akowa Exchange Company – via an official letter on June 17 that they would be blacklisted from regional and international financial networks due to allegations of money laundering. Houthi authorities are likely to respond. Overall, the escalating economic warfare between the warring parties is narrowing the space for financial institutions and businesses to operate in the country.

If members of the Yemeni Exchangers Association decided to close their branches for a longer period, this could destabilize the Yemeni rial. Yemeni money exchangers are key conduits for currency transfers and a mass closure would likely reduce the flow of remittances entering Yemen. This would hinder an essential lifeline for many people struggling to deal with the country’s economic collapse and humanitarian crisis. Money exchange companies are also vital for domestic transfers. Before the conflict escalated in March 2015, less than 10 percent of Yemenis had a bank account and thus money exchange companies are the primary means of transferring money domestically.

Economic Developments in Brief

- June 17: The manager of the central bank branch in Al-Mahra, Juman Awad Juman, met with local banks and fuel importers to discuss measures to enhance the circulation of cash in the governorate. Juman also implored fuel importers to deposit revenues from domestic fuel sales in Yemeni bank branches in Al-Mahra.[57]

- June 23: The Houthis appointed Mohammed Yahya Mohammed Ghober as General Executive Manager of the National Bank of Yemen. The National Bank of Yemen (NBY) is the only bank in Yemen that is headquartered in Aden. The decision to appoint Ghober and enhance the authority of the Sana’a-based NBY can be interpreted as an indirect riposte from the Houthis to previous Yemeni government moves made regarding the banking sector, such as the establishment of a parallel administration for CAC Bank in Aden, headed by Hamid al-Hamdani.

Humanitarian Developments

World Food Programme Partially Suspends Aid Deliveries in Sana’a

The World Food Programme (WFP) announced on June 20 that it was partially suspending assistance to the capital Sana’a over the diversion of food aid in Houthi-controlled areas.[58] The move came after negotiations broke down with Houthi authorities on introducing controls that would ensure aid reached vulnerable Yemenis. An investigation by The Associated Press released in December 2018 revealed that aid deliveries were being stolen on a massive scale and sold on the open market in Houthi-controlled areas, and that Houthi authorities were engaging in fraud by manipulating the lists of beneficiaries and falsifying records.[59]

WFP Executive Director David Beasley had issued a final warning during a June 17 briefing to the UN Security Council.[60] Beasley said that despite improvements in early 2019, WFP had continued to receive reports about food aid theft. One-third of respondents to a survey in Sa’ada governorate, the ancestral heartland of the Houthi movement, had not received food aid in April, he said. Beasley acknowledged reports of food diversion were not unique to Houthi-controlled areas, but said the Yemeni government had demonstrated willingness to cooperate in solving aid delivery challenges in areas under its control.

The WFP and Houthi authorities disagree on using biometric data registration to identify beneficiaries and monitor distribution.[61] The biometric system – which employs iris scanning, fingerprint and facial recognition to ensure aid deliveries reach intended recipients – is currently used in areas controlled by the internationally recognized government. However, Houthi authorities have rejected it, saying it runs “counter to national security.”[62]

Beasley told the Security Council that signed agreements with authorities in Sana’a were never implemented.[63] In May, the WFP had threatened to begin the phased suspension of operations in Houthi-controlled areas if no agreement could be reached.[64]

In a June 21 interview with Reuters, Beasley called on what he described as “good Houthis” to reach an accommodation with the UN agency while accusing “hardliners” within the movement of only caring about profiteering and destabilization.[65] He said he and his teams had been in contact with Houthi leaders, including Abdulmalik al-Houthi, to discuss solutions. With agreement on a control mechanism for deliveries, the WFP head said operations in the capital could resume “within hours.”

The move to suspend aid delivery in Sana’a City initially will affect 850,000 people, the WFP said. Nutrition programs targeting malnourished children, pregnant women and nursing mothers in the capital will continue to operate. Beasley has warned the WFP would consider suspending food aid in other areas of Yemen as well.[66] Overall, Beasley described the humanitarian situation in the country as “catastrophic” and said 20 million people did not have enough to eat.[67] In May, the WFP delivered monthly rations, cash, or vouchers to 10.2 million people in the country.[68]

MSF CRASH: Aid Delivery Lacks Transparency, Severity of Yemen’s Humanitarian Crisis Overblown

Aid operations in Yemen lack transparency and UN agencies have relinquished management of aid distribution to local political authorities, according to new research by members of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).[69] The report also said that the characterization of the humanitarian crisis in Yemen as “the worst in the world” was probably inaccurate.

Conclusions of the research were shared on June 20 by MSF’s Centre de Réflexion sur l’Action et les Savoirs Humanitaires (MSF CRASH), essentially an internal think tank that conducts research on MSF actions and aid practices in the field. The report noted that in Houthi-held areas, the WFP has given responsibility for aid operations to the ministries of Health and Education, despite their lack of independence from the belligerents. While partnerships with governing administrations are not unique to Yemen, the report highlighted the lack of UN control over implementation in Yemen and the massive quantities of aid involved in the country. It also noted that UN agencies operating in Yemen published scarce details or data about their work, or about how funding was allocated or used. Regarding food aid, publicly available data is limited to the number of people receiving food nationally, with no accounting of how this number is calculated, MSF CRASH said.

The report said UN organizations were promoting descriptions of the situation in Yemen that were disconnected from the reality on the ground. The frequently used characterization of Yemen’s humanitarian crisis as the “worst in the world” was likely incorrect, the report said, adding that it was impossible to accurately assess the humanitarian situation in Yemen. Aid workers interviewed by MSF staff pointed to problems with the diagnostic tools used to classify food insecurity, difficulties in accessing parts of the country and pressure by belligerents to inflate figures. MSF teams on the ground had encountered pockets of malnutrition, but these did not indicate a pre-famine or famine situation. The report also said many organizations were surprised at the discrepancy between very high reported levels of food insecurity and low mortality and malnutrition indicators.

Despite these issues, MSF CRASH said figures from UN OCHA’s financial tracking system showed Yemen has received more than US$11.2 billion in aid since 2015.[70] The Saudi government said in April that coalition countries had contributed more than $US18 billion in support of the Yemeni people over the last four years.[71]

UN Humanitarian Chief Urges Donors to Fulfill Pledges

In a June 17 briefing to the UN Security Council, UN humanitarian chief Mark Lowcock urged donors to fulfil their pledges to Yemen, noting that only 27 percent of the $4.2 billion needed for the 2019 humanitarian response had been received.[72]

Lowcock said access constraints had prevented or delayed aid deliveries to more than 1.5 million people in April and May, while dozens of pockets of famine-like conditions have been confirmed across Yemen.

For the second straight month, Lowcock sounded the alarm about the potential dangers related to the SAFER oil tanker moored off the Red Sea Coast (for more information, see An Environmental Apocalypse Looming on the Red Sea).[73] If the tanker were to rupture or explode, an estimated 1.1 million barrels of oil could pollute the Red Sea. He noted that Houthi-affiliated authorities granted permission in June for an assessment team to visit the SAFER tanker. A senior official at SAFER told the Sana’a Center that as of the end of June, the assessment had not been conducted.

- June 4: Houthi forces arrested dozens of people in Ibb and Dhamar governorates who celebrated Eid al-Fitr on June 4, Al Masdar reported.[74] Riyadh announced that the holiday marking the end of Ramadan would begin June 4, while Houthi authorities declared June 5 the first day of Eid. Those arrested were released after signing pledges not to support Saudi Arabia. This is likely the first time in 1,400 years that people living within Yemen’s current geographic boundaries have celebrated Eid on different days.

- June 25: More than 80,000 people in Yemen have been affected by flash floods and torrential rain, among them displaced people in makeshift shelters, the International Organization of Migration reported.[75] The worst-affected governorates were Aden, Abyan, Hajjah, Ibb and Taiz governorates, the IOM said.

- June 29: Airstrikes by the Saudi-led military coalition killed at least seven members of one family, including a woman and four children, in Taiz governorate, Yemeni officials told The Associated Press.[76]

The lush mountains of the Al-Udayin area of Ibb governorate, pictured June 17, 2019 // Photo Credit: Asem Alposi

International Developments

Western Countries’ Arms Sales to Riyadh Face Increasing Scrutiny

Congressional, court and media scrutiny of arms sales and military support to Saudi Arabia put some western governments on the defensive in June, though promises were made and steps are being taken to keep the weapons flowing.

Concerns about arms sales to the kingdom and its coalition allies fighting in Yemen increased after the October 2018 killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. Criticism grew louder in the US Congress and restrictions were imposed in some European countries, but June reports provided some details about recent deals as well as ongoing commercial and military cooperation. Newly released results of a UN inquiry on the Khashoggi killing, which described a gruesome premeditated murder and coverup, could fuel fresh scrutiny. The inquiry found “credible evidence” that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman should be investigated in Khashoggi’s killing and urged the international community to sanction individuals allegedly involved, including the crown prince [see ‘UN Expert: Mohammad bin Salman Should be Investigated in Khashoggi Killing’].[77]

United States: Congress Targets ‘Emergency’ Arms Sales

US lawmakers took steps in June to block the Trump administration’s plan to bypass Congress and push through US$8 billion in emergency arms sales including bombs, ammunition and aircraft maintenance support to Saudi Arabia, citing the prospect of war with Iran for its urgency.[78] Rare bipartisanship allowed measures blocking the sales to pass the Senate, but despite certain US House agreement, President Donald Trump already has promised to veto the measures.

Trump made clear in a June 23 interview with NBC News that he prioritizes US jobs and economic development over humanitarian concerns in Yemen and Khashoggi’s killing. Saudi Arabia buys “massive amounts” of military equipment, which translates into American jobs, Trump said, adding: “That means something to me.”[79]

United Kingdom: Court Orders Reassessment of Weapons Exports

A British court ordered the government to reconsider its arms export licenses to Saudi Arabia because it had not assessed whether the Saudi-led military coalition had violated international humanitarian law in Yemen. The decision does not stop sales, but the government – which plans to appeal – said it would not grant new arms export licenses to Saudi Arabia while it considers the judgment.

Just ahead of the UK Appeals Court ruling, The Guardian detailed in its own investigation just how lucrative and deep the commercial defense relationship is with Saudi Arabia, with thousands of jobs and tens of billions of pounds a year at stake.[80] The report concluded that without the flow of UK military equipment, half of the Saudi Royal Air Force fleet would be grounded within weeks.[81] A former official from the UK Ministry of Defense told the Guardian that Riyadh’s participation in the conflict was dependent on BAE Systems, which provides services — and 6,300 personnel — to Saudi Arabia under contract to the British government.

The investigation also highlighted that UK government officials were aware of the Saudi air force’s questionable targeting practices. A former senior British official told The Guardian that Yemeni government officials would receive WhatsApp messages claiming there were Houthis at a location shared via Google Maps pins. “On that basis, an awful lot of the targeting was conducted without any verification whatsoever,” the former official said.

Switzerland: Bern Bans Aircraft Maker from Saudi Arabia, UAE

On June 26, Switzerland banned Pilatus Aircraft Ltd from operating in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.[82] Pilatus provides technical support, replacement parts management and repairs to its PC-21 aircraft in the Middle East. The Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) found that these services amounted to logistical support, and that providing them to the armed forces of Saudi Arabia and the UAE breached the Federal Act on Private Security Services Provided Abroad as they were incompatible with Swiss foreign policy objectives. The FDFA ordered Pilatus to discontinue these services to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and reported it to the Attorney General for failing to declare its activities.

France: Arms Sales to Riyadh Jump 50%

Paris acknowledged in June it had sold around 1 billion euros worth of arms to Saudi Arabia in 2018, a 50 percent rise on the previous year, saying its arms export procedures comply with international treaties.[83]

At the United Nations

UN Expert: Mohammad bin Salman Should be Investigated in Khashoggi Killing

The release of a UN inquiry on June 19 into the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi brought fresh scrutiny of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman and his potential role in the October 2018 killing.[84] The report, by UN Special Rapporteur Agnes Callamard, said Khashoggi was “the victim of a deliberate, premeditated execution, an extrajudicial killing for which the state of Saudi Arabia is responsible under international human rights law.” Callamard found “credible evidence” that the crown prince should be investigated in the killing, maintaining it required significant government coordination, resources and finances. Every expert consulted by the UN special rapporteur found it “inconceivable” that the crown prince could have been wholly unaware of the operation, according to the report.

The UN special rapporteur said investigations by Saudi Arabia and Turkish authorities in Istanbul, where the killing took place, had failed to meet international standards. The crime scene, she said, was “thoroughly, even forensically” cleaned by a Saudi team, which may amount to obstructing justice. Meanwhile, she said the ongoing trial of 11 alleged suspects in the killing in Saudi Arabia, “fails to meet procedural and substantive standards” and should be suspended.

The report concluded that the murder was an “international crime” over which states could claim universal jurisdiction. Among the recommendations, the report called on the UN to initiate a follow-up criminal investigation into the execution; the US to open an FBI investigation and to determine the responsibility of the Saudi crown prince; and the international community to impose sanctions on individuals allegedly involved in killing Khashoggi, including the crown prince.

Saudi Minister of Foreign Affairs Adel al-Jubeir dismissed the report’s findings as “baseless accusations.”[85]

UN: No Houthi Presence at Hudaydah Ports

No Houthi forces have been detected in Hudaydah’s three strategic ports since their declared unilateral withdrawal in May, the UN mission responsible for monitoring a cease-fire in the governorate said in June.

Coast Guard forces were maintaining security at the ports of Hudaydah, Salif and Ras Issa, General Michael Lollesgaard, head of the Redeployment Coordination Committee (RCC), reported in a statement released June 12.[86] The United Nations Mission in Support of the Hudaydah Agreement (UNMHA) has not witnessed any Houthi military presence at those ports since beginning regular patrols May 14, according to the statement.

The long-stalled pullout was part of the Stockholm Agreement, the UN-mediated deal signed by the internationally recognized Yemeni government and the armed Houthi movement in December 2018.[87] Houthi forces’ withdrawal took place May 11-14 under UN supervision[88] and drew a fiery response[89] from the Yemeni government, which argued it was not genuine and violated past resolutions. The Yemeni government also demanded[90] As the Sana’a Center has previously noted, according to international diplomatic sources who spoke with the Center, Houthi leader Abdelmalik al-Houthi had told the UN special envoy on several occasions since summer 2018 that the armed Houthi movement was willing to remove its troops from the ports and submit to UN supervision of port operations. However, Al-Houthi had insisted that Houthi-appointed personnel would remain in control of port operations.[91]

Lollesgaard said in his statement that the United Nations was unable to verify whether the Coast Guard was operating with the agreed-upon 450 personnel. He also noted that while military manifestations had been dismantled in Salif and Ras Issa ports, useable military positions remained in Hudaydah port; he called on Houthi authorities to remove all of these, specifically trenches.[92]

Lollesgaard urged the warring parties to finalize negotiations on outstanding issues so both phases of the Hudaydah withdrawal plan could be carried out concurrently. In a June 10 letter[93] to the UN Security Council, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said his special envoy for Yemen, Martin Griffiths, also was facilitating negotiations on the issue. The two-phase withdrawal envisions redeploying fighters 18 to 30 kilometers from Hudaydah, allowing for total demilitarization of the city and the return of civilian life.[94]

The UN special envoy briefed the Security Council on June 17 about Hudaydah and progress fulfilling the Stockholm Agreement. He noted that the number of civilian casualties in Hudaydah governorate had been reduced by 68 percent in the five months after the cease-fire came into effect, down from some 1,300 civilian casualties in the five months prior.[95] Griffiths called on the parties to agree on withdrawing from the city and stressed he prioritized elements of the deal related to port revenues. UN-mediated talks in May between Houthi and Yemeni government delegations in Amman had failed to reach an agreement on what to do with revenues from Hudaydah’s ports.[96] Houthi negotiators had sought an agreement on port revenues that would entail the Yemeni government paying civil servant salaries in Hudaydah and across Yemen; the government position was that an agreement on port revenues would entail them paying salaries in Hudaydah governorate, and then taking a gradual approach to paying salaries in remaining northern areas. At the UNSC in June, Griffiths said he hoped to build on the Amman meetings and hold discussions with both sides in the near future. The Sana’a Center spoke with both the Yemeni government and Houthi delegations to the Amman talks, and both reported that, as of the end of June, there had been no followup on the Amman talks.

The special envoy also expressed disappointment about the lack of progress on the prisoner and detainee exchange agreed to during the Stockholm talks. President Hadi specifically raised this issue in a letter he sent to the UN Secretary-General on May 22 rebuking Griffths’ conduct.[97] A diplomatic source told the Sana’a Center that Griffiths had informed the Security Council he would move on prisoner-exchange discussions if no further progress was made on Hudaydah. Such a meeting likely would be in the Jordanian capital of Amman, the source said, where two rounds of unsuccessful talks regarding a prisoner exchange were held in January and February 2019.[98]

Countries Affirm Support for UN Yemen Envoy

Security Council members tried to heal the rift between the Yemeni government and Griffiths following their disagreement over Houthi forces’ withdrawal from the Hudaydah ports (for more information, see The Yemen Review: May 2019).[99] On June 10, the Security Council publicly “underlined its full support” for the special envoy.[100] It also called on all parties to “engage constructively and continuously” with Griffiths, an implicit rebuke of President Hadi’s threat in May to cease cooperation.

Hadi had sent a letter May 22 to the UN Secretary-General in which he threatened to stop cooperating with Griffiths. Guterres, through a UN spokesperson, quickly expressed full confidence in his special envoy.[101] However, he also offered to open a dialogue on Hadi’s concerns, and Rosemary DiCarlo, under-secretary-general for political affairs and peacekeeping, was dispatched to Riyadh.

On June 10, the same day as the Security Council declaration, Saudi Foreign Minister Ibrahim al-Assaf affirmed the kingdom’s support for Griffiths [102] DiCarlo also met with Hadi while in Riyadh to discuss Griffiths’ work and how to move ahead with the Stockholm Agreement.

Signs of reconciliation could be seen at Griffiths’ June 17 briefing to the Security Council. Yemeni Ambassador Ali Fadhel al-Saadi told the council that the internationally recognized government was determined to “cooperate with the UN special envoy.”[103] According to a Sana’a Center diplomatic source, Griffiths later highlighted this during closed-door consultations, noting that this was the first such statement since Hadi had threatened to cease cooperation in May. This change in course, the source noted, came after UNSC members had been pressuring the Yemeni government to calm tensions and work constructively with Griffiths.[104] In a further effort to mend relations, Griffiths met June 22 with Yemeni Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar in Riyadh.[105]

In the United States

Acting Secretary of Defense Steps Down, Withdraws Nomination

On June 18, President Donald Trump announced that Patrick Shanahan had stepped down as acting secretary of defense and had withdrawn his nomination for the job.[106] Mark Esper, secretary of the army and a former executive at the defense firm Raytheon, replaced Shanahan and is expected to be nominated for the permanent position. This will likely further extend what is already the longest period that the Pentagon has gone without a confirmed chief, after Secretary of Defense James Mattis stepped down in December 2018. On the same day as Shanahan’s resignation, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo visited CENTCOM headquarters in Tampa, Florida, where he met with Commander Lt. Gen. Kenneth McKenzie to discuss escalating tensions with Iran.[107] This was an unusual move by a secretary of state, whose remit lies in the diplomatic sphere. Pompeo and National Security Advisor John Bolton, both considered hawks on Iran who see the armed Houthi movement as an Iranian proxy force, have been increasingly forceful in directing Washington’s Iran policy in recent months, both in regards to Yemen and the wider Middle East.

This report was prepared by (in alphabetical order): Ali Abdullah, Waleed Alhariri, Ryan Bailey, Hamza al-Hamadi, Hussam Radman, Gregory Johnsen, Spencer Osberg, Hannah Patchett, Ghaidaa al-Rashidy, Susan Sevareid, Sala al-Sakkaf and Holly Topham

The Yemen Review – formerly known as Yemen at the UN – is a monthly publication produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. Launched in June 2016, it aims to identify and assess current diplomatic, economic, political, military, security, humanitarian and human rights developments related to Yemen.

In producing The Yemen Review, Sana’a Center staff throughout Yemen and around the world gather information, conduct research, and hold private meetings with local, regional, and international stakeholders in order to analyze domestic and international developments regarding Yemen.

This monthly series is designed to provide readers with contextualized insight into the country’s most important ongoing issues.

Endnotes

- Nasser Karimi and Jon Gambrell, “Iran shoots down US surveillance drone, heightening tensions,” The Associated Press, June 20, 2019, https://www.apnews.com/e4316eb989d5499c9828350de8524963.

- Patrick Tucker, “How the Pentagon Nickel-and-Dimed Its Way Into Losing a Drone”, Defense One, June 20, 2019, https://www.defenseone.com/technology/2019/06/how-pentagon-nickel-and-dimed-its-way-losing-drone/157901/

- Donald J Trump Twitter Post, June 21, 2019. https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1142055388965212161.

- Martin Chulov and Julian Borger, “Iran-US dispute grows over attacks on oil tankers in Gulf of Oman,” The Guardian, June 15, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/15/iran-us-divisions-deepen-over-gulf-of-oman-oil-tankers-attack.

- “Statement from US Central Command on attacks against U.S. observation aircraft,” US Central Command, June 16, 2019, https://www.centcom.mil/media/statements/statements-view/article/1877252/statement-from-us-central-command-on-attacks-against-us-observation-aircraft/.

- Nicole Gaouette, “US sending 1,000 additional troops to Middle East amid Iran tensions,” CNN, June 18, 2019, https://edition.cnn.com/2019/06/17/politics/us-additional-troops-iran-tensions/index.html.

- “Yemen and the region: joint statement by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, the UK and the US,” UK Foreign & Commonwealth Office, June 23, 2019, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/statement-by-saudi-arabia-the-uae-the-uk-and-the-us-about-the-situation-in-yemen-and-the-region.

- Patrick Wintour, “Iran says progress made in nuclear talks is still not enough,” The Guardian, June 28, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/28/world-powers-iran-nuclear-deal-abandoned-us.

- “Treasury Targets Senior IRGC Commanders Behind Iran’s Destructive and Destabilizing Activities,” US Department of the Treasury, June 24, 2019, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm716; Patrick Wintour, “Iran’s ultimatum on breaching nuclear deal puts EU3 on the spot,” The Guardian, June 26, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/26/iran-ultimatum-on-breaching-nuclear-deal-puts-eu-3-on-the-spot.

- Patrick Wintour, “Iran breaks nuclear deal and puts pressure on EU over sanctions,” The Guardian, July 1, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jul/01/iran-breaks-nuclear-deal-and-puts-pressure-on-eu-over-sanctions; David E. Sanger, “European Talks With Iran End, Leaving Nuclear Issue Unsettled,” The New York Times, June 28, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/28/us/politics/europe-iran-nuclear-deal.html.

- “Command of the Joint Forces of the Alliance ‘Coalition to Support Legitimacy in Yemen’: Attack on Abha International Airport by Houthi Terrorist Militia Supported by Iran and Targeting Civilians,” Saudi Press Agency, June 24, 2019, https://www.spa.gov.sa/1937370.

- “The Yemeni Aviation is again attacking the Abha and Jizan airports,” الطيران اليمني المسير يهاجم مجددا مطاري أبها وجيزان السعوديين, Al-Masirah, June 23, 2019, https://www.almasirah.net/details.php?es_id=41504&cat_id=3.

- “Coalition Forces Command Alliance Support for Legitimacy in Yemen: A terrorist act targeting Abha International Airport,” Saudi Press Agency, June 24, 2019. https://www.spa.gov.sa/1933676.

- “Allied Forces Command Coalition Support for Legitimacy in Yemen: A Rejected Extrusion Killed by the Iranian-backed Houthi Terrorist Militant Near the Brother’s Desalination Plant,” Saudi Press Agency, June 20, 2019. https://www.spa.gov.sa/1936330.

- Yahya Sarea Facebook Post, June 19, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=622060211609586&id=100014168372521.

- “Yemen’s Houthi group says will target UAE, Saudi vital military facilities,” Reuters, May 19, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-houthi/yemens-houthi-group-says-will-target-uae-saudi-vital-military-facilities-idUSKCN1SP0PZ.

- “Yemen’s Houthis launch drone attack on Saudi-led coalition military parade in Aden, “ Reuters, June 3, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security/yemens-houthis-launch-drone-attack-on-saudi-led-coalition-military-parade-in-aden-idUSKCN1T30V7?feedType=RSS&feedName=worldNews&utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+Reuters%2FworldNews+%28Reuters+World+News%29.

- Yahya Sarea Facebook Post, June 6, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=613743839107890&id=100014168372521.

- “Statement from US Central Command on attacks against U.S. observation aircraft,” US Central Command, June 16, 2019, https://www.centcom.mil/media/statements/statements-view/article/1877252/statement-from-us-central-command-on-attacks-against-us-observation-aircraft/.

- “U.S.: Saudi Pipeline Attacks Originated From Iraq,” Isabel Coles and Dion Nissenbaum, Wall Street Journal, June 29, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-saudi-pipeline-attacks-originated-from-iraq-11561741133.

- “An Environmental Apocalypse Looming on the Red Sea — The Yemen Review, May 2019,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, June 6, 2019. https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7504#Houthis-Attack-Saudi-Pipeline.

- “In conjunction with the arrival of Sudanese troops .. Emirati troops leave Aden” بالتزامن مع وصول قوات سودانية.. قوات إماراتية تغادر عدن. Al Masdar Online, June 22, 2019. https://almasdaronline.com/articles/168817.

- Elana DeLozier, “UAE Drawdown May Isolate Saudi Arabia in Yemen”, July 2, 2019, The Washingron Institute, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/uae-drawdown-in-yemen-may-isolate-saudi-arabia

- Aziz El Yaakoubi and Lisa Barrington, “Exclusive: UAE scales down military presence in Yemen as Gulf tensions flare,” Reuters, June 28, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-exclusive/exclusive-uae-scales-down-military-presence-in-yemen-as-gulf-tensions-flare-idUSKCN1TT14B.

- Elana DeLozier, “UAE Drawdown May Isolate Saudi Arabia in Yemen”, July 2, 2019, The Washingron Institute, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/uae-drawdown-in-yemen-may-isolate-saudi-arabia

- “Shabwa: Three members of the government forces were injured in clashes with gunmen backed by the UAE,” شبوة.. إصابة ثلاثة من افراد القوات الحكومية بمواجهات مع مسلحين مدعومين من الامارات

- “Pro-UAE forces assault Socotra governor’s convoy and Minister of Fisheries,” Al Masdar Online, June 18, 2019. https://almasdaronline.com/article/pro-uae-forces-assault-socotra-governors-convoy-and-minister-of-fisheries.

- “Local authorities explain the latest military developments in Socotra,” Aden Al Ghad, June 19, 2019. https://adengd.net/news/391674/.

- Ibid.

- “Condemned the violence carried out by pro-UAE .. A stop in Socotra to support the legitimate authorities,” نددت باعمال عنف قام بها موالون للامارات.. وقفة في سقطرى لدعم السلطات الشرعية, Al Masdar Online, June 24, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/168911.

- Zach Vertin, “Red Sea Rivalries: The Gulf, the Horn, and the new geopolitics of the Red Sea”, Brookings Institute, June 26, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/research/red-sea-rivalries-the-gulf-the-horn-and-the-new-geopolitics-of-the-red-sea/

- “Al-Mahra.. Tribal people intercept Saudi military convoy in Shihen Directorate,” Al Masdar Online, June 3, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/168233/.

- Kareem Fahim and Missy Ryan, “Saudi Arabia announces capture of an ISIS leader in Yemen in US-backed raid,” The Washington Post, June 25, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/saudi-arabia-announces-capture-of-islamic-state-leader-in-yemen-in-us-backed-raid-backed/2019/06/25/79734ca2-976a-11e9-9a16-dc551ea5a43b_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.d2d1a3a98210

- “هذه تفاصيل إلقاء القبض على زعيم تنظيم داعش في اليمن” (“The details of the capture of a Daesh leader in Yemen,”) Independent Arabia, June 25, 2019, https://www.independentarabia.com/node/35801/الأخبار/العالم-العربي/هذه-تفاصيل-إلقاء-القبض-على-زعيم-تنظيم-داعش-في-اليمن.

- “Joint Forces Command of the Coalition to Restore Legitimacy in Yemen: Saudi Special Forces Capture Leader of Daesh (ISIS) Branch in Yemen,” Saudi Press Agency, June 25, 2019, https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewfullstory.php?lang=en&newsid=1938103#1938103.

- “Counter Terrorism Designations,” US Department of the Treasury, October 25, 2017, https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20171025.aspx; “Treasury and Terrorist Financing Targeting Center Partners Issues First Joint Sanctions Against Key Terrorists and Supporters,” US Department of the Treasury, October 25, 2017, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/sm0187.aspx.

- Aaron Y. Zelin, “New release from Al-Qa’idah in the Arabian Peninsula: ‘Statement’.” Jihadology, June 4, 2019, https://jihadology.net/2019/06/04/new-release-from-al-qaidah-in-the-arabian-peninsula-statement-2/.

- Elisabeth Kendall Twitter Post, June 8, 2019, https://twitter.com/Dr_E_Kendall/status/1137266320867844097.

- “ بينهم قيادي بارز.. مقتل خمسة من عناصر القاعدة بغارات يعتقد انها امريكية في البيضاء” (“Five Al-Qaeda members, including senior leader, killed by suspected US air strike in al-Bayda”), Al Masdar Online, June 25,2019, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/168912.

- “Yemeni FM Khaled Al-Yemany submits his resignation: Al Arabiya,” Al Arabiya, June 10. https://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/gulf/2019/06/10/Yemeni-FM-Khaled-Al-Yemany-resigns-Al-Arabiya.html.

- “Urgent: Hadi leaves for America,” Al-Mashad Al-Yemeni, June 16, 2019. https://www.almashhad-alyemeni.com/136373.

- Economic Committee Facebook Page, June 22 2019, https://bit.ly/2KAE5z9.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Beyond the Business as Usual Approach: Combating Corruption in Yemen”, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 10, 2018, sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/6614

- Economic Committee Facebook Page, June 26, 2019, https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=382832005679393&id=272799003349361.

- “Beyond the Business as Usual Approach: Combating Corruption in Yemen”, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 10, 2018, sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/6614

- Economic Committee Facebook Page, June 16, 2019, https://bit.ly/2LdyEWA.

- Mansour Rageh, Amal Nasser and Farea Al-Muslimi, “Yemen Without a Functioning Central Bank: The Loss of Basic Economic Stabilization and Accelerating Famine”, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, November 2, 2016, sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/55.

- “Yemen president names new central bank governor, moves HQ to Aden,” Reuters, September 18, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-cenbank/yemen-president-names-new-central-bank-governor-moves-hq-to-aden-idUSKCN11O0WB.

- “A crucial agreement in the city of Jeddah between Mayad and Al-Aradah on linking the bank in Marib with the Central Bank in Aden,” Aden al-Ghad, June 1, 2019, https://bit.ly/2IDC2Iy.

- Hafedh Mayad Facebook Page, June 7, 2019, https://bit.ly/2ZLjxrf. Accessed June 24, 2019.

- Official Yemeni Exchangers Association document seen by the Sana’a Center on June 19, a copy of which is available upon request.

- Official Yemeni Exchangers Association and Yemen Banks Association document seen by the Sana’a Center on June 20, a copy of which is available upon request.

- Ibid.

- Sana’a Center interview on July 19, 2019.

- “Meeting in Al Mahrah discusses the activation of the monetary cycle in the banking system,” Yemen News Agency (SABA), June 17, 2019, https://www.sabanew.net/viewstory/50696.

- “World Food Programme begins partial suspension of aid in Yemen,” World Food Programme, June 20, 2019, https://www1.wfp.org/news/world-food-programme-begins-partial-suspension-aid-yemen.

- Maggie Michael, “AP Investigation: Food aid stolen as Yemen starves,” The Associated Press, December 31, 2018, https://www.apnews.com/bcf4e7595b554029bcd372cb129c49ab.

- “United Nations Officials Urge Parties in Yemen to Fulfil Stockholm, Hodeidah Agreements, amid Security Council Calls for Opening of Aid Corridors,” United Nations Meetings Coverage and Press Releases, June 17, 2019, https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sc13845.doc.htm.

- Aziz El Yaakoubi and Lisa Barrington, “Yemen’s Houthis and WFP dispute aid control as millions starve,” Reuters, June 4, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-wfp/yemens-houthis-and-wfp-dispute-aid-control-as-millions-starve-idUSKCN1T51YO.

- “UN gives ultimatum to Yemen rebels over reports of aid theft,” The New Humanitarian, June 17, 2019, http://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2019/06/17/un-yemen-rebels-aid-theft-biometrics.

- “Yemeni children ‘dying right now’ due to food aid diversion Beasley warns,” UN News, June 17, 2019, https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/06/1040651,

- “World Food Programme to consider suspension of aid in Houthi-controlled areas of Yemen,” WFP, May 20, 2019, https://www1.wfp.org/news/world-food-programme-consider-suspension-aid-houthi-controlled-areas-yemen.

- Michael Holden “WFP hopeful Yemen’s ‘good’ Houthis will prevail to allow food aid suspension to end,” Reuters, June 21, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-wfp/wfp-hopeful-yemens-good-houthis-will-prevail-to-allow-food-aid-suspension-to-end-idUSKCN1TM1YR.

- “United Nations Officials Urge Parties in Yemen to Fulfil Stockholm, Hodeidah Agreements, Amid Security Council Calls for opening of Aid Corridors,” United Nations, June 17, 2019, https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sc13845.doc.htm.

- “Yemeni children ‘dying right now’ due to food aid diversion Beasley warns,” UN News, June 17, 2019, https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/06/1040651,

- “Emergency Dashboard – May 2019,” World Food Programme, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/WFP-0000105646.pdf

- MSF noted several of its members had contributed to its study and that its conclusions were based on reviews of aid organization documents and interviews with aid workers in Yemen. “Yemen: questions about an aid system,” MSF Crash, June 20, 2019, https://www.msf-crash.org/en/blog/war-and-humanitarianism/yemen-questions-about-aid-system.

- “Humanitarian aid contributions,” Financial Tracking Service, UN OCHA, https://fts.unocha.org.

- “KSA and UAE provide USD200 million in humanitarian assistance to Yemen,” Embassy of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia – Washington D.C., April 9, 2019, https://www.saudiembassy.net/news/ksa-and-uae-provide-usd-200-million-humanitarian-assistance-yemen.

- “Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock Briefing to the Security Council on the humanitarian situation in Yemen,” Relief Web, June 17, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/under-secretary-general-humanitarian-affairs-and-emergency-relief-coordinator-mark-19.

- “An Environmental Apocalypse Looming on the Red Sea — The Yemen Review,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, May 2019. https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7504.

- “ لاحتفائهم الثلاثاء بالعيد.. الحوثيون يخطفون عشرات المدنيين في ذمار وإب” (For their celebration Tuesday Eid .. Houthis kidnapped dozens of civilians in Dhamar and Ibb), Al Masdar, June 4, 2019, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/168259.

- “IOM helps nearly 30,000 people in Yemen rebuild shelters destroyed by floods,,” International Organization for Migration, June 25, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/iom-helps-nearly-30000-people-yemen-rebuild-shelters-destroyed-floods.

- Ahmed Al-Haj, “Yemeni officials say Saudi airstrikes kill 7,” June 29, 2019, The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/yemeni-officials-say-saudi-led-coalition-airstrikes-kill-7/2019/06/29/fdf161bc-9a53-11e9-9a16-dc551ea5a43b_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.99fcd1463277.

- “Annex to the Report of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions: Investigation into the unlawful death of Mr. Jamal Khashoggi,” United Nations Human Rights Council,

- Susannah George, “Senate votes to block Saudi arms sales as Trump vows veto,” The Associated Press, June 20, 2019, https://www.apnews.com/4169fdfbcd0a411b914b2e22fb21e932.

- “President Trump’s full, unedited interview with Meet the Press,” NBC News, June 23, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/meet-the-press/president-trump-s-full-unedited-interview-meet-press-n1020731.

- Arron Merat, “‘The Saudis couldn’t do it without us’: the UK’s true role in Yemen’s deadly war,” The Guardian, June 18, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/18/the-saudis-couldnt-do-it-without-us-the-uks-true-role-in-yemens-deadly-war.

- Arron Merat, “‘The Saudis couldn’t do it without us’: the UK’s true role in Yemen’s deadly war,” The Guardian, June 18, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/18/the-saudis-couldnt-do-it-without-us-the-uks-true-role-in-yemens-deadly-war.

- “FDFA bans Pilatus from supplying services in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates,” Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, June 26, 2019, https://www.admin.ch/gov/en/start/documentation/media-releases.msg-id-75587.html.

- John Irish, “French weapons sales to Saudi jumped 50 percent last year,” Reuters, June 4, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-defence-arms/french-weapons-sales-to-saudi-jumped-50-percent-last-year-idUSKCN1T51C0.

- “Annex to the Report of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions: Investigation into the unlawful death of Mr. Jamal Khashoggi,” United Nations Human Rights Council, June 19, 2019. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session41/Documents/A_HRC_41_CRP.1.docx

- Nick Hopkins and Stephanie Kirchgaessner, “‘Credible evidence’ Saudi crown prince liable for Khashoggi killing – UN report,” The Guardian, June 19, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/19/jamal-khashoggi-killing-saudi-crown-prince-mohammed-bin-salman-evidence-un-report.

- “Note to Correspondents: United Nations Mission to Support the Hudaydah Agreement – Statement by the Chair of the Redeployment Coordination Committee,” United Nations Secretary-General, June 12, 2019, https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/note-correspondents/2019-06-12/note-correspondents-united-nations-mission-support-the-hudaydah-agreement-statement-the-chair-of-the-redeployment-coordination-committee.

- “Full Text of the Stockholm Agreement,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, December 13, 2018, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/full-text-stockholm-agreement.

- “Note to Correspondents: Statement by the Chair of the Redeployment Coordination Committee,” United Nations Secretary-General, May 14, 2019. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/note-correspondents/2019-05-14/note-correspondents-statement-the-chair-of-the-redeployment-coordination-committee-scroll-down-for-arabic.

- “Letter dated 13 May 2019 from the Permanent Representative of Yemen to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council,” signed by Yemeni Ambassador Abdullah Ali Fadhel Al-Saadi, May 13, 2019. https://undocs.org/pdf?symbol=en/S/2019/386.

- Ibid.

- “An Environmental Apocalypse Looming on the Red Sea — The Yemen Review, May 2019”, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, June 6, 2019, sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7504#Hudaydah-and-the-Stockholm-Agreement

- “Note to Correspondents: United Nations Mission to Support the Hudaydah Agreement – Statement by the Chair of the Redeployment Coordination Committee,” United Nations Secretary-General, June 12, 2019, https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/note-correspondents/2019-06-12/note-correspondents-united-nations-mission-support-the-hudaydah-agreement-statement-the-chair-of-the-redeployment-coordination-committee.

- “Letter dated 10 June 2019 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations, June 12,2019, https://undocs.org/S/2019/485.

- Edith Lederer, “UN Envoy: Yemen parties agree on initial Hodeidah withdrawals,” The Associated Press, April 15, 2019, https://www.apnews.com/8f254a6838f54166bf7a5ab50f7904a8

- “Briefing of the UN Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen to the Open Session of the UN Security Council,” Office of the UN Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, June 17, 2019, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/briefing-un-special-envoy-secretary-general-yemen-open-session-un-security-council.

- Spencer Osberg and Hannah Patchett, “An Unending Fast: What the Failure of the Amman Meetings Means for Yemen”, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, May 20, 2019, sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/7433

- “An Environmental Apocalypse Looming on the Red Sea — The Yemen Review,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, May 2019. https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7504.

- “The Supervisory Committee on the Implementation of the Prisoner Exchange Agreement Continues its Work,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, February 8, 2019, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/supervisory-committee-implementation-prisoner-exchange-agreement-continues-its-work.

- “An Environmental Apocalypse Looming on the Red Sea — The Yemen Review,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, May 2019. https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/7504.

- “Security Council Press Statement on Yemen,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary General for Yemen, June 10, 2019, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/security-council-press-statement-yemen.

- “In Addition to the Presidential Extension Letter, Guterres Renews ‘Confidence’ in Griffith,” News Yemen, May 25, 2019, https://www.newsyemen.net/news41847.html.

- “Saudis Express Support for Embattled UN Yemen Envoy,” France 24, June 10, 2019, https://www.france24.com/en/20190610-saudis-express-support-embattled-un-yemen-envoy.

- “United Nations Officials Urge Parties in Yemen to Fulfil Stockholm, Hodeidah Agreements, amid Security Council Calls for Opening of Aid Corridors,” United Nations Meetings Coverage and Press Releases, June 17, 2019, https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sc13845.doc.htm.

- Diplomatic sources told the Sana’a Center in May that several P5 ambassadors to Yemen met with President Hadi in Riyadh to express their support for Griffiths in an effort to reduce tensions.

- “UN Special Envoy Meets with the Government of Yemen in Riyadh to Advance the Peace Process in Yemen,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, June 26, 2019, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/un-special-envoy-meets-government-yemen-riyadh-advance-peace-process-yemen.

- Donald J Trump Twitter Post, June 18, 2019. https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1141027593774346240.

- “Pompeo at Centcom: ‘Trump does not want war with Iran,” Rachel Franzin, The Hill, June 18, 2019. https://thehill.com/policy/defense/449109-pompeo-at-centcom-trump-does-not-want-war.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

Children from

Children from