The Sana’a Center Editorial

The Sana’a Center Editorial

The Drowning of Dissent

For the past few years, women have been abducted in northern Yemen, disappeared, tortured, raped, forced into false confessions of prostitution, and left traumatized and stigmatized, their punishment for publicly contradicting Houthi authorities. This has been an open secret in Sana’a that independent Yemeni journalists on the ground should have been investigating, corroborating and publishing to shine light into every shadowed corner that nurtures such atrocities.

It is impossible, however, for journalists in northern Yemen to do the sort of work that holds authorities to account when any dissenting voice that rises above a whisper is silenced, whether press, activist or ordinary citizen. Independent journalism hasn’t existed in Sana’a since the Houthis seized power in September 2014 and media organizations began shutting down, leaving only hand-picked sectarian propaganda outlets in their wake. Along with the closures, 10 journalists were abducted in 2015, jailed and tortured. Such a climate of fear breeds self-censorship among those left standing — play by the rules or lose your job, your freedom, your dignity, and perhaps even your life — and silences important stories like those of the abused women.

The climate was only poisoned more on April 11, when a deeply flawed “trial” concluded for the abducted journalists, whose charges included spying for the anti-Houthi military coalition. Four of them — Abdel-Khaleq Amran, Akram al-Walidi, Hareth Hamid and Tawfiq al-Mansouri — were sentenced to death, and six others convicted with them were ordered released on time served. By month’s end, only one, Salah al-Qaedi, was free. The journalists had been forcibly disappeared for six months, tortured, denied medical treatment and deprived of their right to due process. The Houthis lack any legal or constitutional legitimacy to run courts, meaning carrying out the sentences would amount to extrajudicial killings.

Houthi authorities are well aware of the threat independent journalism is to a regime that relies on corruption, intimidation, violence and abuse — though their animosity runs surprisingly deep. They have shown reckless disregard toward journalists again and again, including when they held Abdullah Kabil and Yousef Alaizry captive in 2015 in a building that had been repeatedly bombed only for them to be buried in its rubble on its next hit. Furthermore, since the war began, the Houthis have exchanged prisoners with Al-Qaeda, released hundreds of enemy forces’ fighters and, most recently, offered an exchange for five Saudi soldiers including a pilot shot down over Al-Jawf in February, but have rejected every call for the release of the journalists now on death row, rebuffing foreign and domestic mediation attempts. A soldier may kill you, but apparently it’s worse if a journalist reveals your true nature.

Laudable international calls to protect journalists are being made now around World Press Freedom Day — including some urging the Houthis to quash the verdicts and free Yemen’s jailed journalists. Yemeni journalists outside Houthi-run territory shouldn’t be forgotten either in media freedom calls, where journalists have been intimidated into silence or other professions and attacked and detained by various forces, though generally released more quickly than those who fall into Houthi authorities’ hands.

These days, in light of the broader threat of COVID-19 and the inability to socially distance in prisons, many regional countries including Saudi Arabia, Iran, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kuwait, Jordan and Turkey have freed prisoners as part of their efforts to curb the spread of the virus. For the most part, releases thus far haven’t included political prisoners held on the sort of security charges that would include journalists. In Yemen, the government and the Houthis also have released several hundred prisoners combined to ease crowding, but journalists and political opponents don’t appear to have been among them. With coronavirus spreading now in Yemen, authorities on both sides of the frontlines must go further and release political detainees, including all of the journalists held by the Houthis.

As long as journalists worldwide are vilified for doing their jobs and disagreeable news is dismissed as “fake news,” the Houthis and others in the region who take undermining independent journalism to its extreme will feel little pressure to change their ways. However, efforts to restart the political process in Yemen have picked up steam, and there is a risk Houthi human rights abuses toward any independent thinkers will be tacitly accepted for the greater goal of ending the war. That cannot be allowed to happen. Any such compromise of basic rights — allowing all unscrupulous sides to reach a consensus that these rights don’t matter — will, in the long term, only lead to more bloodshed and oppression.

Regional authoritarian regimes cannot be expected to show concern for such human rights abuses, so the United Nations and European countries will need to push the Houthis, and other parties, to free journalists and other political prisoners. If such behavior remains unchallenged and expediency trumps human rights in a cease-fire and political settlement, the world is once again saying that when it comes to persecuting journalists, activists and dissidents, brutality is acceptable toward your own people if it provides stability and protects the interests and borders of your wealthier neighbors.

Contents

Yemen Records First COVID-19 Cases, Deaths

War and Pandemic: A Viral Storm Blows In

Yemen Records First COVID-19 Cases, Deaths

Yemen announced its first official cases and confirmed deaths from COVID-19 in April, with the coronavirus cases emerging in Hadramawt, Aden and Taiz. The pandemic’s spread to Yemen heightened fears of how devastating the weeks ahead will be, given the country’s failing health system, people’s weakened immunity and warring parties’ inability to pause fighting and respond together to the threat. The UN said on April 28 there was “a very real probability” the coronavirus had been circulating undetected and unmitigated within Yemeni communities in the 17 days since the first case was confirmed in the country, based on transmission patterns in other countries.[1] This increased the likelihood a surge in cases would overwhelm the health system, the UN said.

The first official deaths from COVID-19 in Yemen were announced April 29, while the number of confirmed cases in the country had reached 10 by May 2.[2] The health minister for the Yemeni government, Nasser Baoum, told Yemen TV that two people had died from COVID-19 in Aden on April 29.[3] Seven cases have been confirmed in Aden, two in Taiz, and one in Hadramawt.[4] Two sources told Reuters that at least one case of COVID-19 had been confirmed in Sana’a, but the Houthi health ministry denied this.[5] Confirmed cases worldwide had exceeded 3.2 million with more than 225,000 deaths by April 30.[6]

Local Authorities Limit Movement, Close Mosques; Hospital Workers Protest

After a case of COVID-19 emerged in Taiz, the governor closed the governorate’s borders, except for essential supplies, and ordered mosques to close.[7] The coronavirus appeared to have spread to Taiz from Aden: The first patient in Taiz had arrived from Aden on April 27, and had been in contact with the second confirmed case in Taiz.[8] In response to the cases in Aden, the Southern Transitional Council (STC) announced a three-day curfew in the port city, beginning midnight on April 29, and ordered a ban on qat sales and a two-week closure of malls, restaurants and mosques.[9] The STC also said the borders of all southern governorates would be closed, although the transport of goods including relief supplies and food would be allowed.

Several hospitals closed after the announcement of new cases, local media reported.[10] The Cuban Hospital and Al-Wali Hospital announced they had closed on April 30 due to fears over the coronavirus. In several other hospitals, including the biggest in Aden, Al-Jumhuriya Hospital, medical staff walked out due to a lack of preparedness to handle the coronavirus, including insufficient Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Attorney-General Ali Al-Awash ordered an investigation into allegations hospitals were refusing to treat suspected COVID-19 cases in Aden.[11]

Brief Curfews After Yemen’s First Case Worried Hadramawt Health Workers

Yemen’s first confirmed COVID-19 patient, recorded on April 10, was a 60-year-old Yemeni man who worked at Al-Shihr port in Hadramawt governorate.[12] In response, local authorities closed the port for deep cleaning and ordered port workers to self-isolate for two weeks, while neighboring governorates Shabwa and Al-Mahra suspended travel to and from Hadramawt. Hadramawt’s governor announced a daily 22-hour curfew in Al-Shihr, Al-Dis Al-Sharqiya and Qusayar on April 10, with the rest of the governorate put under a nightly curfew.[13] Earlier in April, Hadramawt’s governor had imposed a 12-hour nightly curfew in the governorate’s major cities after appeals for people to stay home and avoid gatherings were ignored.[14]

However, life continued as normal in Al-Shihr on April 11, the day after the announcement of the curfew, with businesses and markets open and cars entering and leaving the town.[15] Hadramawt’s governor lifted the daily curfew on April 12.[16] Hospital workers at Al-Shihr hospital, where the COVID-19 patient was being treated, protested on April 12 to demand additional PPE, testing and training on dealing with COVID-19.[17] They also called for a 24-hour lockdown and an awareness-raising campaign on social distancing and the risks of COVID-19.

Earlier in April, healthcare workers in Mukalla, a port city in Hadramawt, held a protest to demand PPE after being forced to treat a patient with suspected COVID-19 without gloves or masks.[18] Tests later revealed the patient, who died, had dengue fever, which causes respiratory problems, muscle aches and fever similar to COVID-19. Floods in March and April have led to a resurgence of dengue fever, putting further strain on a collapsing health system bracing to confront the coronavirus. Al-Shihr Hospital was treating hundreds of patients suffering from dengue fever in early April.[19] Healthcare workers are increasingly concerned about treating patients presenting with dengue fever symptoms, the director of the National Malaria Control Program told Arab News.[20] Local authorities have not carried out insecticide spraying to curb the spread of dengue fever due to a lack of funds, Arab News reported.

Authorities in South and North Respond with Test Kits, Closures, Spraying

After the first COVID-19 case was confirmed in Hadramawt, some attempts were made to mitigate the spread elsewhere in Yemen. The Yemeni government allocated $9 million in additional funding for the health sector and said 3,000 test kits had been sent to Hadramawt to expand screening procedures.[21] Local authorities asked those who had been in contact with the patient to self-isolate due to a shortage of tests.[22] The World Health Organization (WHO) also sent ambulances, medical equipment, ventilators, medical supplies and disinfectants to Hadramawt.[23]

Yemen’s borders, airports and schools were closed in mid-March. Yemen’s internationally recognized government had instructed governors to implement strict measures to prevent the spread of the virus, leading to different approaches among governorates nominally under government control. Houthi and Yemeni government authorities had released hundreds of prisoners by early April to reduce the potential spread of an outbreak.[24] The Yemeni government said it had opened 27 quarantine centers in nine governorates.[25] By mid-April, the STC also announced a nightly curfew from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m.

The health minister in Houthi-held Sana’a, Taha al-Mutawakil, said on April 4 that Yemen’s health sector was critically under-resourced in terms of hospital beds, ventilators and tests.[26] Houthi authorities reduced staff levels in ministries and administrative departments in Sana’a to 20 percent, and dispatched security forces to border areas to prevent the smuggling of migrants.[27] A spokesperson for the interior ministry in Sana’a said a large number of smugglers had been arrested and thousands of migrants had been quarantined in Sa’ada, where 28 quarantine centers were established. More than 5,500 people had been quarantined in Sa’ada by April 11, according to Houthi authorities.[28] In Sana’a, field teams sprayed streets, markets, hospitals and government facilities to sterilize them.[29] Training was held for security forces in Taiz and Ibb on precautionary measures to deal with the coronavirus; to raise awareness on health guidelines and preventative measures in Hajjah; and to train hospital staff in Sana’a on the epidemiology of the coronavirus, infection prevention measures, and testing and reporting procedures.[30]

Prior to the announcement of new cases on April 29, measures were being eased across Yemen. Houthi authorities on April 18 lifted a ban on people entering Houthi-controlled territory from governorates under government control.[31] The nightly curfews in Hadramawt were lifted on April 23, and mosques were allowed to reopen.[32]

UN Anticipates 16 Million Will Catch COVID-19, 300,000 Require Hospitalization

Modellers anticipate COVID-19 could spread faster, more widely and with deadlier consequences in Yemen than in most other countries due to high levels of acute vulnerabilities, low levels of general immunity and a fragile health system, UN Humanitarian Coordinator Lise Grande said on April 27.[33] The UN is basing its response on the most likely scenario, Grande said, which envisions suppression will not be as effective as hoped and 16 million people will be infected, requiring 300,000 hospital beds and 200,000 ICU beds. The strategy in Yemen is based on suppression, detection and treatment of cases and public education, as well as trying to protect the health system so it can still treat people with other chronic diseases such as cholera, diphtheria, dengue fever and malaria, Grande said.

The WHO said 37 hospitals were being prepared across Yemen to treat COVID-19 patients and announced plans to triple the number of Rapid Response Teams, which have been deployed to every district in the country, from 333 to 999.[34] These teams are responsible for detecting, assessing and responding to suspected COVID-19 cases. The WHO said on April 23 it had distributed 520 ICU beds and 208 ventilators, while hundreds more had been purchased and were awaiting distribution; 6,700 tests had been distributed and an additional 32,400 tests were due to arrive in Yemen in the coming weeks. In addition, Emergency Operations Centers established during the cholera epidemic were being repurposed to treat COVID-19. The International Initiative on COVID-19 in Yemen, a private sector initiative, said April 22 that a shipment of 49,000 virus collection kits, 20,000 rapid test kits, five centrifuges and equipment that would enable 85,000 tests, and 24,000 COVID-19 nucleic acid test kits would reach Yemen toward the end of the month.[35]

The outlook remains bleak. Yemen has only three doctors and seven hospital beds per 10,000 people, according to the UNDP, and just half the country’s health facilities are fully operational, while two-thirds of Yemenis have no access to basic healthcare.[36] Frequent handwashing will be difficult as half the population lacks reliable access to safe water, and many communities — particularly the 3.6 million who are internally displaced — will struggle to practice social distancing. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) also warned COVID-19 could spread quickly in Yemen’s overcrowded cities and IDP camps, while rural areas had barely any health facilities and “little or no possibility” of testing or instituting public health measures like effective social distancing.[37] MSF noted the severe lack of testing capacity in Yemen, which it said may have been the reason Yemen was among the last countries to register a case of COVID-19.

In Photos: Life in the Time of Coronavirus

A local aid worker offers hand sanitizer to people collecting monthly food baskets in Hajr al-Sa’air district of Hadramawt on April 12, 2020 // Sana’a Center photo by Mohammed Haian

People gather at a food vendor’s cart in Al-Qatn, Hadramawt, on April 14, 2020 // Sana’a Center photo by Mohammed Haian

A youth wears a mask in the market at Al-Qatn, Hadramawt, on April 14, 2020. Days after Yemen’s first recorded case of COVID-19 in Hadramawt’s port of Al-Shihr, masks and gloves were a rare sight nationwide, with people wary of their cost and the stigma of wearing them // Sana’a Center photo by Mohammed Haian

Shoppers prepare for Ramadan at Souk al-Milh (the Salt Market) in Sana’a on April 22, 2020. Yemen’s first COVID-19 case was reported earlier in April, but masks and gloves remained a rare sight in several markets around Yemen // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

Shoppers prepare for Ramadan at Souk al-Milh (the Salt Market) in Sana’a on April 22, 2020. Yemen’s first COVID-19 case was reported earlier in April, but masks and gloves remained a rare sight in several markets around Yemen // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

Despite worries about the spread of coronavirus, shoppers preparing for Ramadan crowd the old market in Bab al-Yemen, Sana’a, on April 22, 2020 // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

In Focus: Yemenis Fear Starvation More Than COVID-19

By Rim Mugahed

As a patchwork of curfews, closures and quarantines were imposed across Yemen in April to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, many Yemenis feared starvation more than the virus itself. Even before the numbers of confirmed cases began to rise at the end of April, some Yemenis who spoke to the Sana’a Center were already reeling from the economic impact of containment measures in a country where, after five years of war, the path from job loss to destitution is short and steep.

In Sana’a, Houthi authorities ordered some businesses to close to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, including gyms, shisha cafes, wedding halls, salons and some shops. This left Iqbal, a widow who worked at a cosmetics shop, with no salary. Struggling to feed her children, Iqbal said she had sold her furniture to buy food. A bank employee in Sana’a, Liza, said she and her colleagues were told to stay home on annual leave, but that once leave allowances were used up, staff would be put on half-pay. Like others across Yemen, she said she feared being unable to buy food. Meanwhile Shaker, who works in the pharmaceutical industry, said trade had been sluggish since restrictions were imposed in Sana’a, but some sectors were profiting, including grocery stories. Some products thought to help combat the coronavirus have sold out, he said, noting Vitamin C supplements were out of stock. Many businesses in Sana’a did not abide by the new regulations: Some parks and shisha cafes closed, but others stayed open, as did some salons and gyms. While wedding halls were closed, some people held wedding parties at home.

In Hadramawt, where the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed on April 10, Mohammad al-Katheri said a nightly curfew had caused losses for daily wage workers like street vendors. Al-Katheri, who works as a peace trainer, said 80 percent of his work had been canceled due to COVID-19. Meanwhile, stocks of some basic goods had run out. Very few people were wearing face masks in Hadramawt, aside from NGO workers, a resident of the central Al-Qatn district of Hadramawt said. Those who did wear face masks were laughed at and called “coronavirus”, and people would not shake their hands or go near them, fearing they were ill, the resident said.

In Wadi Hadramawt, Zahra al-Abed, who works in women’s development, said she and her colleagues were trying to raise awareness of World Health Organization guidelines, and to provide assistance to daily wage laborers with help from businessmen and supporters. Hisham Bajaber, a lawyer in Hadramawt, said he had been forced to stop work on some cases, but continued to work in a government department, where no gloves or sanitizer were provided. The announcement of the first COVID-19 patient on April 10 led to panic buying, he said, and some sectors, like toy stores, were profiting from the COVID-19 measures. Many other shops were suffering, however. Zaki Jamal, who owns a stationery shop in Aden’s Dar Saad district, said the closure of schools had severely reduced his sales, for what he viewed as “unnecessary precautions.”

Maged, an army officer in Sheikh Othman district in Aden, said most people were unaware of the scale of the threat from COVID-19, and also said those who wore face masks or practiced social distancing were mocked. Shops in Aden were withholding their stocks of face masks hoping to raise prices once the pandemic reached the city, he said, although many people in Sheikh Othman could afford face masks in any case. Government salaries are irregularly paid, and Maged works part-time as an accountant at a restaurant; he considered quitting this job after COVID-19 reached Yemen, but could not afford to. Ibtihal al-Ansari, who works at a bank in Aden, said she was constantly in contact with lots of people through her work, but could not afford to stop work.

Ahlam Taha was studying for a master’s degree in Sana’a, but after Houthi authorities closed universities and restricted movement between cities, she returned to her home city of Taiz, preferring to be with her family in the event of a full lockdown. She and her siblings bought face masks but were ostracized for doing so, and treated as if they were carrying the coronavirus. Taha said new restrictions made travel even more difficult than usual in Taiz city, which is split between government and Houthi control. Sa’eed Al-Sharaabi, a social worker and trainer, said those who left Houthi-controlled areas of Taiz could not return, while those who entered were being quarantined for 14 days. This has been disastrous for factory workers who live in government-held areas but work in Taiz’s industrial area, which is under Houthi control, he said. Taiz lacks healthcare and social care, as well as services like online shopping, which makes it difficult for people to stay at home. Several residents of Taiz complained of soaring prices.

Across Yemen, people said life had changed for the worse; some families have stopped children from going out, but those in small houses — especially those without electricity — were struggling to keep their children indoors, while most adults cannot afford to stay home and must work to survive. Many expressed hope Yemen would evade the coronavirus, but the months to come are likely to bring stricter measures should the virus spread. These will leave many Yemenis in an unwinnable bind: Few can afford the cost of containment, or the price of the coronavirus.

Rim Mugahed is a sociologist, novelist and non-resident researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. Her work on Yemen includes research into women’s issues, especially pertaining to police and prisons, and transitional justice.

Developments in Yemen

Saudi-Led Coalition Announces Cease-Fire as UN Pushes Peace Talks

A concerted push by the United Nations in April to halt the recent uptick in violence in Yemen and bring the warring parties back to the negotiating table saw the Saudi-led coalition unilaterally declare a temporary cease-fire. The armed Houthi movement, meanwhile, released its own plan to end the conflict, which included a laundry list of demands that Saudi Arabia must meet before it would agree to a halt in fighting. Despite reports the two sides had renewed indirect talks and the UN special envoy pushing a revised plan for the resumption of the political process, fighting on the ground and airstrikes continued through the month in several frontline areas.

Saudi-Led Coalition Declares, Extends Unilateral Cease-Fire

Saudi Arabia announced a unilateral cease-fire on April 8, saying the move was to support UN-led efforts to restart peace talks amid the looming threat from the novel coronavirus.[38] In March, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres had called for a global humanitarian cease-fire to confront the threat from COVID-19. In an interview with Al-Arabiya, coalition spokesperson Turki Al-Malki expressed hope that the Houthis would respond in kind and said Saudi Arabia backed a political solution to the conflict.[39] The cease-fire announcement was welcomed by the UN Secretary-General and the UN Security Council and endorsed by the internationally recognized Yemeni government.[40]

Houthi officials, including movement spokesperson Mohammed Abdel Salam and political council member Mohammed al-Bukhiti, characterized the announced cease-fire as a hoax and said the group would not agree to any temporary deal that does not involve the Saudi-led coalition lifting its “siege” on the country.[41] The Houthi movement, which has the military initiative on the ground, appears to be using its current strength and opponents’ weakness to press for broader concessions as part of any agreement to a halt in fighting. The Houthi unwillingness to enter into any temporary cease-fire also may stem from a desire to deny government and coalition forces time to reorganize their ranks and defenses.[42]

On April 15, Reuters reported that the Saudis and Houthis had resumed indirect talks on implementing a truce.[43] Oman also promised it would soon hold a meeting between the Saudis and the Houthis, a diplomatic source told the Sana’a Center. The unilateral cease-fire expired on April 23 without ever truly taking effect amid a Houthi rejection and violations from all sides, including continued Saudi airstrikes. Still, the Saudi-led coalition announced a month-long extension on April 24, citing a request from the UN envoy, concerns over the spread of COVID-19 in Yemen, and consideration for the holy month of Ramadan, which began on April 23.[44]

Saudi Arabia’s push to halt the recent fighting comes as it is politically exhausted and being drained financially from five years of war against the Houthis. The Saudi leadership also is aware of the Hadi government’s difficulty in managing areas and groups under its control, and it continues to lose territory to the Houthis despite years of coalition financial and military support. Taking advantage of the COVID-19 crisis to offer a unilateral cease-fire could help Riyadh present itself as a responsible peace broker as it tries to find a way out of the war.

The cease-fire extension is a logical step for Saudi Arabia that also eases international pressure on the Saudis related to Yemen and allows it to focus on containing the spread of COVID-19 within the kingdom and the financial consequences associated with it.

Houthis Release Peace Plan Demanding Coalition Withdrawal

On the same day as the Saudi-led coalition’s cease-fire announcement, the Houthi movement unveiled its own plan for ending the conflict in Yemen. Reflecting its commanding position vis-à-vis the coalition and the Yemeni government, the Houthi vision for peace reads more as a list of preconditions for the movement to agree to any cease-fire and includes only token concessions. The maximalist positions articulated by the Houthis[45] are reminiscent in tone to UNSC Resolution 2216 – passed by the Secretary Council in 2015 ordering the Houthis to unilaterally end fighting in Yemen and allow the Yemeni government to return to power in Sana’a. Both were, in essence, calls for surrender. The Houthis’ three-part plan leaves little room for negotiation and notes that the group would only adhere to a cease-fire once the document is agreed to and signed by the coalition.[46]

The first section calls for an immediate and comprehensive cease-fire. This would include: a halt in the movement of military forces and heavy and medium weapons and ammunition; a stop to all operations directed against the territory of Yemen and those from Yemen (a likely reference to Houthi cross-border missile and drone attacks into Saudi Arabia); and it calls on both sides to halt negative discourse in public statements and in the media. The plan also envisions UN supervision and implementation mechanisms, including a military coordination committee and joint operations center – composed of representatives from both sides and chaired by the UN – to monitor the cease-fire.

The second section explicitly demands an end to the coalition blockade of Houthi-held territory and articulates measures needed to alleviate the humanitarian situation in the country. The Houthi plan says the coalition must lift all restrictions on movement into and out of Yemen by sea, air and land, most notably reiterating the group’s long-standing demand for the reopening of Sana’a airport. It also outlines a host of payments that the Saudi-led coalition must make akin to reparations. This includes paying public sector salaries in accordance with 2014 payroll lists and opening a special account to pay salaries for a decade until Yemen’s economy recovers, and compensating citizens affected by the war; it specifies compensation for all those who lost a house, factory, market or business as well as all those who were directly or indirectly injured or killed during the war. The mention of 2014 payroll lists is notable and represents a potential concession, as past efforts to negotiate the payment of public sector salaries have been stymied by the Houthis’ demand that recipients should reflect the current payroll, which includes a significant influx and integration of Houthi loyalists and also more general changes of personnel brought about by sickness and retirement. Finally, the Houthis demanded that the coalition must restore all buildings damaged by the fighting, notably excluding any mention of whether this would also include buildings damaged and destroyed by Houthi attacks.

The third section shows how the Houthi movement is ready to engage with its Yemeni rivals toward a political settlement. The plan envisions an agreement with the Saudi-led coalition, not the Yemeni government, as the first step before moving toward discussions on the political future of the country with Yemeni counterparts. This third section is by far the shortest in the plan and gives little detail on how a successful and lasting compromise might be forged. However, it does single out the UN as the party to lead negotiations related to Yemen’s political structure post-conflict after an initial deal between the coalition and the Houthis is agreed, and says that any final agreement will be subject to a national referendum. There were no official responses to the Houthis’ proposal from the coalition or the Yemeni government.

Special Envoy Presents New Plan as Mediation Efforts Move Online

Following the Saudi cease-fire declaration and the Houthi release of its peace vision, UN Special Envoy for Yemen Martin Griffiths announced on April 10 that he had distributed a revised plan to halt the recent fighting.[47] Like the Houthi proposal, the envoy’s plan contains three parts: a nationwide cease-fire; economic and humanitarian initiatives; and the resumption of the political process. During a briefing to the UN Security Council on April 16, Griffiths said the proposed humanitarian and economic measures – including reopening Sana’a airport, paying civil servant salaries and ensuring open road and port access to facilitate the entry of essential goods into the country – would help Yemen in its fight against COVID-19.[48]

The special envoy told the UNSC that he had held discussions with the warring parties over the past two weeks and saw them moving toward a consensus, noting that he expected an agreement in the “immediate future.”[49] Privately, however, Griffiths singled out the Houthis as the main obstacle to a cease-fire deal, according to diplomatic sources at the UN who spoke with the Sana’a Center. Griffiths appeared more pessimistic in his closed briefing to the UNSC than in his public comments, telling UNSC member states they should “never underestimate the parties’ ability to walk away from a good deal tomorrow,” a diplomat who was present told the Sana’a Center. The special envoy also said he would seek to convene virtual video conferences between the two sides.

Commentary: Can Kuwaiti Mediation and Omani Facilitation Support Ending Yemen’s War?

By Kristian Coates Ulrichsen

On April 9, the unilateral announcement of a two-week cease-fire by the Saudi-led coalition raised hopes that a window of opportunity might open to bring an end to its troubled five-year military intervention in Yemen.[50] The fact that the Houthis were not consulted before the cease-fire was declared, and that the Saudis, Emiratis and Yemeni government of President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi lack consensus on the next steps means that attempts to broker a political settlement will be complicated and may yet falter.[51] Although fighting in parts of Yemen continued despite the cease-fire, the prospect of a pause in the conflict is an opportune moment to examine the roles of Kuwait and Oman in deescalation, dialogue, trust-building and diplomacy.[52]

Kuwait and Oman have carved subtly different niches for themselves in the maelstrom of Gulf politics, in contrast to the muscular approach to regional affairs taken by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Oman, during the long rule of Sultan Qaboos bin Said (1970-2020), focused on facilitating talks between adversaries by passing messages and creating the space and conditions for meetings to occur, with the hosting of US-Iran backchannel negotiations in 2012-13 a prominent example.[53] Kuwait has placed greater emphasis on mediation with Emir Sabah al-Ahmad, himself a former foreign minister of 40 years’ standing, often engaging in shuttle diplomacy, as occurred in the opening weeks of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) rift in 2017 that pitted Saudi Arabia and the UAE against Qatar.[54]

Both Kuwait and Oman have a track record of engaging in mediation and facilitation in Yemen. Kuwait acted as a mediator on several occasions during Sabah al-Ahmad’s tenure as foreign minister, including in 1972 after border clashes between (the then-separate) North and South Yemen and again in 1979, when it hosted a reconciliation summit that produced the Kuwait Agreement.[55] [56] Relations between Kuwait and Yemen were strained severely by the newly reunified Republic of Yemen’s failure to condemn Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, and took years to recover.[57] In 2016, however, Kuwait attempted to mediate in the Yemen War when it hosted months of talks between April and August, but failed to bridge the gaps between the parties.[58] Kuwait acted in close coordination with the United Nations and the UN special envoy for Yemen, and the Kuwaiti leadership also focused on Yemen during Kuwait’s two-year term on the UN Security Council in 2018 and 2019.[59]

For its part, Oman has engaged heavily in recent years in passing messages and facilitating backchannel talks between the various parties to the conflict, including domestic Yemeni actors and foreign officials from states closely involved in the broader dimensions of the war, including the United States and Iran.[60] [61] [62] Oman’s western governorate of Dhofar is linked to Yemen’s easternmost governorate of Al-Mahra through webs of cross-border tribal, trading, and socio-economic ties, and since 2015, Omani officials have viewed the growing Saudi and Emirati influence there with some alarm.[63] As the only GCC state that has not participated at any point in the Saudi-led military coalition, the Omanis are seen by many in Yemen as an impartial and trustworthy arbiter.[64] Oman’s ability to talk to all parties has involved meetings with senior Saudi and Houthi officials, along with the current UN special envoy, Martin Griffiths. Notably, Muscat played a key role brokering backchannel Saudi-Houthi talks after the attack on Saudi oil infrastructure in September 2019.[65] [66]

To be sure, the unprecedented impact of COVID-19 has come to dominate policymaking bandwidth as governments around the world have struggled to come to grips with the pandemic, while Oman, especially, has also been hit hard by plunging oil prices since March.[67] This double-hit has complicated Sultan Haitham bin Tariq’s first months in power since he succeeded his cousin Qaboos in January, although the new Sultan has pledged to follow his predecessor’s approach to regional affairs and support the peaceful resolution of disputes.[68] The advent of new leadership in Muscat has been seen by some as an opportunity to reset ties with Saudi Arabia and the UAE that had become strained. The Saudi desire to disengage militarily from Yemen also means that any talks facilitated and hosted by Oman may have more of a chance of expanding into formal and substantive negotiations, just as the US-Iran talks paved the way for the P5+1 process that led to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran in 2015.[69]

The challenge going forward for Kuwait, Oman or any other regional or international party is to identify practical ways to support deescalatory measures and bridge the gaps between the maximalist positions that have undermined previous talks.[70] For an eventual political process to be feasible, and not to suffer the fate of the Kuwaiti mediation in 2016, painstaking and incremental preparatory work will be required to explore which compromises are possible and around what issues, temper expectations so that all sides can build confidence in each other, and agree on parameters for peace negotiations to reduce the risk of subsequent grandstanding and point-scoring.

Kuwait and Oman are well-placed to perform much of the groundwork for an eventual negotiated settlement to end the war in Yemen. They are generally regarded by all sides as sufficiently credible, trustworthy and relatively untainted by too close an association with any one side in the conflict. Their perceived impartiality, coupled with the fact that Kuwaiti and Omani officials are rooted in the political culture of the region, means that Kuwait and Oman may better be able to push the warring parties to overcome years of accumulated distrust that has hampered the UN’s attempts to sustain and support the political track in Yemen.[71]

Kristian Coates Ulrichsen is the Fellow for the Middle East at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

Political Developments

STC Declares Self-Rule in the South

The Southern Transitional Council (STC) dramatically declared self-rule on April 26 in southern areas under its control.[72] The move followed months of fruitless negotiations with the Yemeni government to implement the Riyadh Agreement, the power-sharing deal signed by the two parties under Saudi sponsorship in November 2019. It also came in the immediate wake of heavy flooding that struck the city, causing several deaths and crippling public services (See: ‘Yemen Hit by Torrential Rain, Damaging Floods).

The Riyadh Agreement proposed to integrate the STC politically and militarily within the government by offering it cabinet seats and a position with the delegation for future peace talks, and putting STC military forces under the command of the ministries of defense and interior. However, plans never really progressed beyond negotiating the mechanisms for implementation, with each side accusing the other of stalling and a lack of buy-in. The STC retained security control in Aden and days before the self-rule declaration the Yemeni government accused the group of preventing the return of government officials to the interim capital.[73] The STC’s relationship had grown increasingly fraught not only with the Yemeni government, but also with Saudi Arabia, which assumed overall responsibility for the anti-Houthi coalition following the pullout of the United Arab Emirates – the primary patron of the STC – from Yemen in October 2019.

The STC’s declaration of self-rule was swiftly rejected by several southern governorates, including Al-Mahra, Socotra, Shabwa and Hadramawt. Forces in Shabwa affiliated with the Yemeni government went on alert, while Abyan remained at particular risk of renewed violence due to the presence of frontlines separating STC and pro-Hadi forces from the last round of fighting.[74]

On April 28, the Saudi cabinet called on the STC to halt any moves that ran contrary to the Riyadh Agreement.[75] The Yemeni government, meanwhile, labeled the STC’s announcement as a new coup and sought to undercut the perception that the group had broad support for its actions across the south, noting that many local authorities in the former South Yemen had sided with the government.[76] The UN special envoy, in response to developments in the south, called for expediting implementation of the Riyadh Agreement,[77] which was echoed by the UK Foreign Office.[78] Meanwhile, the US State Department said it was “concerned” about the self-rule declaration and called for engagement between the Yemeni government and the STC.[79]

On May 1, the STC released a follow-up statement saying the self-rule decision was not spontaneous but had been made in response to the “neglect, mismanagement and collective punishment” of the south by the government, citing in particular the halt in civil servant salaries and the deterioration of public services. Notably, the statement did not include any mention of a commitment or return to the Riyadh Agreement, which the STC accused the government of violating. Rather, the STC stressed the importance of including the southern issue in the UN-led peace process, which has generally limited its focus to the Houthi-Yemeni government confrontation.[80]

For a better understanding of the STC’s latest move, Sana’a Center analysts took a look at circumstances surrounding the announcement and how the war has empowered southern players.

Commentary: STC Self-Rule Declaration Airs Sour Relations with Riyadh

Pressure was piling up on the Southern Transitional Council: Its soldiers were not receiving wages, key officials were prohibited from returning to Aden, frontline areas were not receiving support, some of its military commanders’ loyalties were shifting, rival forces were encroaching on their territory, and now with mud and debris filling flood-damaged streets and homes in Aden, its own people were confronting it over public services. So it seems the STC tried to absorb all this by leaping into the unknown and dragging everyone with them.

(The full commentary from Sana’a Center Executive Director Maged al-Madhaji is available here.)[81]

Commentary: The South Rises Again

Five years of civil strife in southern Yemen has given rise to southern centers of power, some oriented toward secession and others seeking the semi-autonomy of a federal system. Their views and causes were contained, however, until the dynamics of the current war increased southern autonomy, ultimately encouraging some southern political elites to declare self-rule. Rooted in the failed rebellion of 1994, the south would generally be subjected to neglect and marginalization moving forward. While 2007 witnessed the birth of renewed southern political mobilization, substantial change in the southern arena began five years ago when Saudi Arabia and the UAE launched Operation Decisive Storm.

(The full commentary from Sana’a Center Research Fellow Hussam Radman can be read here.)[82]

Political Developments in Brief:

- April 2: A court in Aden began criminal proceedings in absentia against 32 Houthi members, including the movement’s leader, Abdelmalek al-Houthi, and the head of the Supreme Political Council, Mehdi al-Mashat, over charges of mounting a coup against the government and endangering the independence of Yemen.[83] The next court hearing is scheduled for July.

- April 9: The Sana’a-based leadership of the General People’s Congress (GPC), the ruling party under the regime of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, dismissed 31 party leaders living outside Houthi-controlled areas, including Speaker of Parliament Sultan al-Barakani, accusing them of harming national unity and improperly convening meetings.[84]

- April 19: Houthi authorities arrested former culture minister Khaled al-Rowaishan at his home in Sana’a.[85] He was released the following day.

Military and Security Developments

Cease-Fire Ignored as Hundreds Killed in April Fighting

Clashes between the armed Houthi movement and forces allied with the Yemeni government continued unabated in April despite the Saudi declaration of a unilateral cease-fire and international calls for a global cease-fire to address the shared threat from COVID-19. Fighting between the sides continued in Marib, Al-Jawf, Al-Bayda and Al-Dhalea governorates, although there was less frontline movement than in previous months. Earlier this year, Houthi forces made rapid-fire advances in Al-Jawf, capturing the governorate capital, Al-Hazm, and began to threaten Marib city. The Associated Press, citing Houthi and government officials, reported on April 22 that more than 500 people had been killed and hundreds more wounded in fighting in April.[86]

The fighting on the ground in April was accompanied by an uptick in air operations by the Saudi-led coalition. According to the Yemen Data Project, April 2-8 was the heaviest week of bombings in the country since July 2018.[87] Riyadh’s declaration of a unilateral cease-fire on April 8 saw the coalition reduce the tempo of air operations, but they still remained well-above the period from end of September 2019 to January 2020, when the coalition and the Houthi movement had agreed to a partial truce on air and missile strikes. A total of 270 airstrikes were recorded during the two-week cease-fire, with air raids in Marib’s Majzr and Al-Jawf’s Khab wa Al-Sha’af – two districts where Houthi and anti-Houthi forces have been engaged in fighting – accounting for 42 percent of all airstrikes.[88]

Marib remained the focus of fighting but there was little movement in frontlines as a three-pronged Houthi offensive was met with a government counterattack. In Majzr district, Houthi advances saw them take over the Tariq bin Ziyad military camp and Al-Jafrah hospital and begin to threaten Maas military camp, the headquarters for the 7th military district coordinating operations along the Nehm front in neighboring Sana’a governorate.[89] Pro-government forces counterattacked later in the month, retaking Al-Jafrah and pushing Houthi forces back to the Tariq bin Ziyad military camp.

Fighting in Marib also continued on the Serwah front, particularly around the Kawfal military base, which has been the site of battles since February. On April 5, the Houthis and the Yemeni government traded blame for an attack on an oil pipeline pumping station near Kawfal.[90] The pipeline, which is no longer operational, had pumped oil from the Safer-run fields in Marib to Ras Issa on the Red Sea in Hudaydah governorate.

On the third front in the north of the governorate, Yemeni government and tribal forces battled the Houthis near the border with neighboring Al-Jawf. Houthi military spokesperson Yahya Sarea claimed on April 19 that the group had repelled government attacks in Marib’s Majzr and Al-Jawf’s Khub wa Al Sha’af districts.[91] On April 24, Yemeni media reported that government forces had seized positions on the Salab Mountain, a highpoint in Nehm district, Sana’a governorate, and were approaching Al-Jawf junction, a strategic crossroad that had been captured by Houthi forces earlier in the year.[92]

The Houthis have also been engaging in outreach efforts with government-aligned tribes, which have borne a large share of the fighting in Marib. This strategy of negotiating an accomodation with local tribes has been used by the Houthis in the past to defuse opposition and facilitate offenses, for example in Al-Jawf and Al-Bayda governorate.

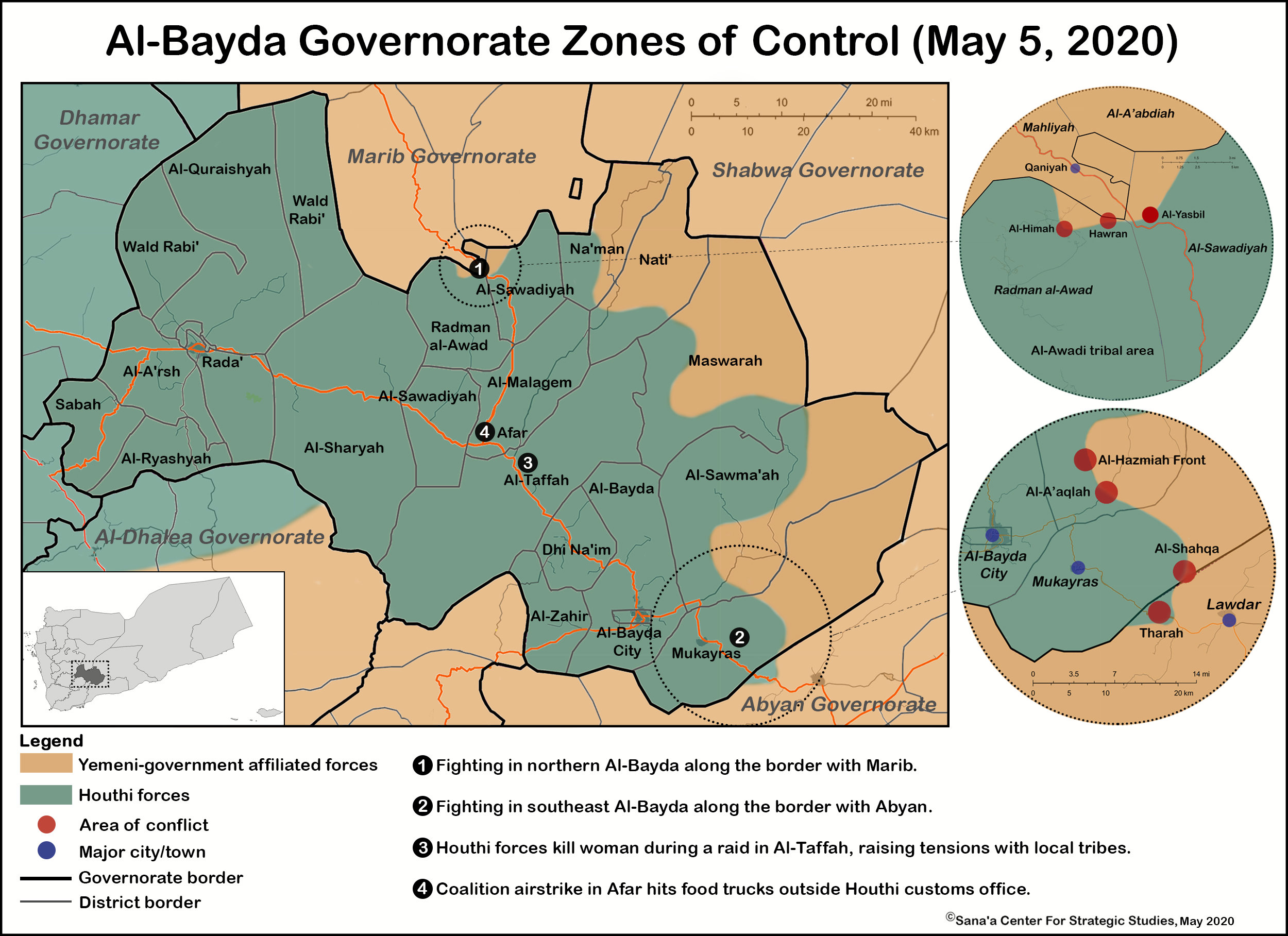

South of Marib, Al-Bayda governorate was a site of escalating violence between the warring parties. Pro-government troops, backed by local resistance groups and coalition airstrikes, launched an offensive on April 7 from southern Marib into the northern part of Al-Bayda.[93] Battles around the Qaniyah border region continued throughout the month and by the start of May pro-Hadi forces had breached Al-Himah and Al-Yasbil, local sources in Al-Bayda told the Sana’a Center. Further south, battles also took place in Mukayras district, which is technically in Al-Bayda but was historically part of neighboring Abyan.[94]

On April 27, the Houthi killing of a local woman in Al-Taffah ratcheted up tension with local tribes. Jihad al-Asbahi was killed when Houthi forces raided the home of her father-in-law, Hussein al-Asbahi. In response, Yasser al-Awadi, a local sheikh who had taken a neutral stand in recent years, called on Al-Bayda’s tribes to confront the Houthis and demand justice for the killing and later threatened the group with war.[95] Houthi media reported that a delegation composed of deputy foreign minister Hussein al-Ezzi, Houthi politburo member, Fadhl Abu Taleb, and Al-Bayda mushrif Abdullah Ali Edrees had visited Sheikh Al-Khadour Abdulrab Al-Asbahi to mediate the issue.[96] However, Sheikh Al-Khadour and Jihad’s father, Brigadier General Ahmed Mohammed al-Asbahi, rejected the Houthi customary arbitration.[97]

On May 2, the Houthi movement announced that a coalition airstrike in Al-Bayda’s Afar area had destroyed trucks carrying imported food and medicine outside a customs office. Local sources confirmed the incident to the Sana’a Center, saying that there was a Houthi military warehouse near the customs crossing and that the bombing had struck many food trucks, killing an unspecified number of people.

Truce Agreed After Pro-STC and Government Forces Clash in Socotra

An attempt by forces loyal to the STC to implement the group’s self-rule decree led to clashes on the island governorate of Socotra before a truce was agreed with local authorities aligned with the Yemeni government. Fighting centered in Haybat, a mountainous district 20 kilometers outside the governorate capital Hadebo, and included the use of tanks, artillery and heavy weapons.[98] The governor of Socotra, Ramzi Mahrous, who had previously declared the governorate’s loyalty to the Hadi government, later said that loyalist troops had prevented the advance of STC-aligned forces toward Hadebo. The May 1 agreement to halt fighting gave coalition and government forces responsibility for securing the governorate capital and local authority facilities while both STC and government-aligned forces agreed to remove checkpoints and military vehicles.[99]

While isolated from the broader conflict, Socotra has seen tension rise during the war over attempts by the UAE to cement its presence on the island strategically situated off the Horn of Africa. In 2018, a Yemeni government complaint to the UN Security Council in 2018 led Abu Dhabi to withdraw some of its troops. However, the UAE continued to back the establishment of proxy security forces in Socotra, similar to other Emirati-backed proxy forces in mainland Yemen. Socotra also has historical and familial ties to the UAE, whose offer of citizenship to a significant number of Socotris in 2018 and 2019 sparked some criticism by opponents of the UAE presence in Yemen.

Yemeni Government Says Hudaydah Cease-Fire ‘Unenforceable’

The cease-fire governing the port city of Hudaydah, established in the 2018 Stockholm Agreement, was becoming “unenforceable”, Yemeni government foreign affairs minister Mohammed al-Hadrami said on April 18.[100] The minister’s comments followed the death of a member of the government team charged with monitoring the cease-fire, Colonel Mohammed al-Sulihi, who was allegedly shot by a Houthi sniper in March.[101] Briefing the UN Security Council in April, special envoy Martin Griffiths said the cease-fire in Hudayah was being violated daily and the UN-led Redeployment Coordination Committee (RCC) had in effect “ceased to function” since the incident.[102] The RCC was established as part of the Stockholm Agreement to negotiate the mutual redeployment of forces in Hudaydah and had established five joint observation posts in the city in October 2019 to monitor the cease-fire.

Military and Security Developments in Brief:

- April 9: The Islamic State group claimed an IED attack against a Houthi vehicle in Juban district, Al-Dhalea governorate, that killed three Houthi fighters.[103] The operation marked the first IS-claimed activity in the southern governorate.

- April 16: Saudi Arabia announced the execution of a Yemeni man convicted of a terror attack against a Spanish dance troupe that was performing in the capital Riyadh.[104] A Saudi court said Emad Abdelqawi al-Mansouri stabbed three people at the event in November 2019 and was acting on the orders of an unnamed Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula leader in Yemen.

Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments

Aid Programs Close as Funding Runs Out

Aid programs were shutting down across Yemen in April as aid agencies faced a funding crisis of “gargantuan proportions,” UN Humanitarian Coordinator Lise Grande said on April 27.[105]

A program to feed moderately or severely malnourished children was closing in the final week of April due to lack of funds, Grande said, adding: “We have to face the fact that without the help that we provide them, they are going to die.” Forced closures to nutrition programs would affect 2.26 million Yemeni children suffering from malnutrition, UN humanitarian chief Mark Lowcock told the Security Council earlier in April.[106] Aid agencies were ending services provided in 142 camps and settlements for internally displaced people, while programs on mine action, protection and reproductive health were also ceasing at the end of the month.

As the coronavirus began to spread in Yemen, UNICEF was forced to stop providing services in 18 major hospitals and 2,500 primary health centers, while the World Health Organization (WHO) was cutting 80 percent of the services it provides in 189 hospitals and 200 primary health centers by the end of April, Grande said. The emergency distribution of hygiene items to confront COVID-19 was also ending, and the WHO had stopped paying incentives and allowances to health workers, many of whom have not received regular salaries for years. Earlier in April, the World Food Programme (WFP) halved the food rations it supplies to Houthi-controlled areas, a move Grande said would affect 8.5 million people.[107]

Briefing the UN Security Council on April 16, Lowcock warned that the UN-led humanitarian response in Yemen was significantly underfunded, with just US$800 million pledged compared to US$2.6 billion at this time in 2019.[108] He said 31 out of 41 major UN programs in Yemen could close within weeks if funds were not secured.

Loss of Donor Confidence Not Yet Restored

Grande said the funding shortfall was due to a loss of donor confidence, driven by onerous restrictions imposed on humanitarian workers, mostly in northern Yemen. These restrictions have hampered humanitarians’ ability to get to people in need to do assessments, monitor programs and deliver aid in a responsible way, Grande said. The UN has urged authorities in Yemen to help improve the operating environment and progress has been made in recent months, Grande said, noting that Houthi authorities had lifted a proposed tax on humanitarian assistance and were allowing aid workers to conduct assessments. But, she said, more had to be done to bridge the confidence gap. In the meantime, Grande appealed to donors to provide “lifeline funding” to allow programs to keep working as negotiations continued with Yemeni authorities.[109]

USAID partially halted funding to NGOs in Houthi-controlled areas on March 28 in response to Houthi interference in aid distribution. An aid worker in Sana’a said the suspension was expected to last until the end of June, when it would be reviewed depending on the outcome of ongoing negotiations with Houthi authorities.[110] Larger organizations with diversified income sources have so far been able to weather the suspension and remain in Houthi-controlled areas, the aid worker said, and USAID is continuing to pay program-related salaries, but some NGOs dismissed some of their support teams due to the reduction in work and financial capacity. Meanwhile several smaller organizations dependent on USAID funds moved their programs to government-controlled areas in order to retain full USAID grants.

In mid-April, international and Yemeni aid groups issued a joint call for USAID to reconsider the funding suspension to ensure Yemen had all possible resources to respond to COVID-19.[111] The aid suspension has already impacted critical programs: the UN has stopped providing energy to Al-Thora Hospital in Hudaydah, which serves more than 600,000 people, the statement said. “Cutting energy for a key hospital as temperatures and risk of COVID-19 rise is a true recipe for disaster,” said Aisha Jumaan, president of the Yemen Relief and Reconstruction Foundation.

Key Donor Pledging Event Delayed

A donor pledging event for Yemen had been scheduled in Riyadh in April, co-hosted by Saudi Arabia and the UN, but was postponed due to international travel restrictions.[112] No new date has been set, but a virtual pledging event may be held after the holy month of Ramadan, a UN official told the Sana’a Center.[113] In February 2019, the High-Level Pledging Event co-hosted by Sweden and Switzerland raised US$2.6 billion in donor pledges to support the humanitarian response in Yemen.[114]

On April 8, Saudi Deputy Defense Minister Khalid bin Salman announced the kingdom would support the UN Humanitarian Response Plan for Yemen with US$500 million and the COVID-19 response in the country with US$25 million.[115] As of April 30, the US$500 million had not been delivered, according to a UN official.[116]

Funding to Yemen from international COVID-19 response plans has been minimal so far. The UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) allocated US$164 million for COVID-19 response measures in 36 countries but Yemen was not among the recipients as of April 28.[117] The UN appealed for US$2.01 billion for its Global COVID-19 Humanitarian Response Plan, under which Yemen had been allocated US$39.4 million by the end of April.[118] On April 2, the World Bank approved a US$26.9 million IDA grant for Yemen as part of its global US$14 billion fast-track package to support developing countries and their COVID-19 responses.[119] The IMF on April 13 approved immediate debt relief for 25 countries including Yemen; it said grants to cover IMF debt obligations for six months aimed to free up resources to respond to the pandemic.[120]

The US is preparing a “substantial contribution” to help Yemen address the coronavirus, a US official told Reuters in April.[121] The tranche would not be channeled through the WHO because of a halt in US funding for the world body. A new directive from the Trump administration required aid agencies to obtain prior written approval from USAID to use US funding for COVID-19 to buy PPE or ventilators, The New Humanitarian reported April 29, apparently in response to US domestic shortages and competing demands for the medical supplies.[122]

COVID-19 Measures Impede Movement of Aid Workers

Airport and border closures and restrictions hindered the work and movement of humanitarian staff in Yemen in April. Houthi authorities stopped issuing visas for aid workers to travel to Yemen, as well as permits required to move around the country, an aid worker in Sana’a said.[123] Houthi authorities also were demanding that aid organizations focus their funds on fighting the coronavirus. The delivery of humanitarian supplies and commercial goods across frontlines was seeing increased delays, leading to increased transport costs, the aid worker said.

The closures of Sana’a and Aden airports in mid-March restricted the entry and exit of humanitarian workers, which was already difficult prior to COVID-19, although a UN flight traveled from Addis Ababa to Aden and back on April 30.[124] An INGO staff member said negotiations had taken place in April to allow aid workers, notably those who are older and more vulnerable to COVID-19, to leave the country and for new staff to enter to prepare for the pandemic, stressing there were insufficient doctors and specialist staff with the experience to respond to COVID-19.[125]

In Photos: ‘Once-in-a-Generation’ Flooding

Residents make their way through the mud and debris left behind by flooding in Crater, Aden, on April 22, 2020 // Sana’a Center photo by Rageh Abdulrab

Mud, damaged cars and debris litter the streets of Crater, Aden, on April 22, 2020, after floods swept through the city // Sana’a Center photo by Rageh Abdulrab

Men try to move a water tank that was dislodged by the floods that hit Marib on April 16, 2020 // Sana’a Center photo by Ali Owaida

Floodwaters fill the streets of As-Sailah, in the Old City of Sana’a, on April 15, 2020 // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

Men wade through floodwaters in Al-Qasemi area of the Old City of Sana’a on April 15, 2020 // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

Shoppers make their way through mud left behind by flooding at Shomailah market in Sana’a on April 14, 2020 // Sana’a Center photo by Asem Alposi

Yemen Hit by Torrential Rain, Damaging Floods

“Once-in-a generation floods” announced the start of the rainy season in 13 governorates, affecting close to 150,000 people across Yemen since mid-April.[126] In Aden, which was among the most affected governorates, flooding killed eight people, including five children.[127] Internally displaced families were hit particularly hard. Five women and two children died in Marib governorate, which has functioned as a comparatively safe haven for displaced people throughout the war. Fourteen camps were affected as of April 16, the deputy governor said.[128] In Marib’s biggest camp, As-Suwayda, which hosts more than 630 IDP families, three children died and a woman and her child went missing.[129] Marib governor Sultan Al-Aradah said affected families would be housed in hotels at the expense of local authorities until the camps are restored.[130] Abyan, Lahj, Sana’a, Ibb and Hajjah governorates were also struck by severe floods, which caused two deaths in Sana’a city.[131] The floods displaced at least 7,000 people and damaged roads, bridges and electricity and water networks.[132]

Houthis Sentence Four Journalists to Death

A Houthi-controlled specialized criminal court in Sana’a sentenced four Yemeni journalists to death in April and six others to time already served.[133]

The Houthis had abducted nine of the 10 journalists in June 2015 from a hotel in the capital, Sana’a, and the tenth journalist two months later, the journalists’ lawyer, Abdel-Majeed Sabra, told the Sana’a Center.[134] All had appeared on lists for prisoner exchange deals in 2017 and 2018, he said, however the Houthi-run prosecutors later referred their cases to court.

Abdel-Khaleq Amran, Akram al-Walidi, Hareth Hamid and Tawfiq al-Mansouri were sentenced to death on spying charges. The court convicted the six remaining journalists of supporting the Saudi-led coalition through “spreading false news and rumors” among other charges, ordering their release upon time served.[135] Salah al-Qaedi, one of the six, was released on April 23, the lawyer said;[136] the others had not been released by month’s end.

The journalists had been deprived of several human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the right to due process, Sabra said; they had been forcibly disappeared for six months, denied medical treatment and subjected to physical and pyschological torture. Sabra said the Houthi-run court did not inform him about court hearings, so they often were held without a defense attorney present. He said he was only allowed to attend the final hearing, during which the verdict was delivered, as an observer.

Numerous national and international rights groups have condemned Houthi authorities’ detention of the journalists and handling of their cases.[137]

Sabra said he would appeal the convictions.

Women Describe Torture, Rape by Houthi Forces in Secret Prisons

Houthi forces are escalating a crackdown on women who dissent or participate in public life, detaining them in a network of secret detention facilities where they are tortured and sometimes raped, an AP investigation has found.[138]

Rights groups say up to 350 women are currently detained in Sana’a, a figure the Yemeni Organization for Combating Human Trafficking said was likely an underestimate, while figures for other govenorates under Houthi control were more difficult to establish.

Women described to the AP being abducted from their homes and the street by gangs of Houthi officers and taken to a network of clandestine makeshift detention facilities. One woman was taken to a remote villa on the outskirts of Sana’a, where about 40 other women were being held. She said she was tortured by Houthi officers, who pulled out her toenails; she was also gang-raped by three masked Houthi officers while female guards held her down. Other women described being beaten, given electric shocks and psychologically tortured.

The detention sites include apartments seized from exiled politicians, hospitals, schools and villas. At least two villas on a main street in Sana’a, Taiz Street, were used along with a former school that held 120 women, including teenagers, teachers and human rights activists, former detainees told the AP. They told AP that Sultan Zabin, head of the Sana’a criminal investigation division, took young girls from the school to rape them. Zabin was identified in a UN Panel of Experts report earlier this year as leading a network that, under the guise of curbing prostitution, used sexual violence and other methods “in the repression of women who oppose the Houthis.”[139]

Women were forced to make fabricated confessions to prostitution and espionage charges on camera before their release.

Houthi forces started rounding-up women in 2017, when scores were detained while protesting to demand the return of the body of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was killed by the Houthis. Since then, the intimidation campaign has expanded to include any woman who speaks out against the Houthis, a former detainee told the AP. A teacher said 18 armed men broke into her home and beat everyone inside after she posted a video on Facebook about the non-payment of government salaries.

The Houthis’ human rights minister, Radia Abdullah, denied any secret women’s prisons existed. She said many women had been arrested for prostitution. The AP found that a parliamentary committee established in 2019 to investigate reports of illegal detention released dozens of men but was closed under pressure from the Houthi-run Interior Ministry before investigating the cases of women.

Humanitarian and Human Rights Developments in Brief:

- April 2: Police in Aden said they were investigating allegations that female IDPs from Hudaydah governorate were raped April 1 by armed men in security uniforms, according to the local newspaper Aden Al-Ghad.[140] An official of Aden’s Security Belt forces told the newspaper it also had formed a committee to investigate.

- April 5: Shelling hit the women’s section of the Central Prison of Al-Mudhaffar district, Taiz governorate, killing at least five women and one child as well as injuring at least 11 others, according to the United Nations.[141] The Yemeni government accused Houthi forces of the shelling, The Associated Press reported.[142] The human rights NGO Mwatana for Human Rights also accused Houthi forces of the attack, saying it killed six women and two girls.[143]

- April 30: Baha’is remained detained in Houthi-controlled prisons. In late March, president of the Houthi Supreme Political Council Mahdi al-Mashat had announced that Baha’i prisoners would be released and a Baha’i leader, who had previously been sentenced to death, would be pardoned.[144]

Economic Developments

Commentary: Yemen Urgently Needs a Unified Fiscal Policy Response to COVID-19

By Amal Nasser

In separately defined containment measures, authorities in Sana’a and Aden closed sea, land and air ports as a precaution prior to the April 10 official reporting of Yemen’s first confirmed case of COVID-19.[145] Since then, they have — separately — suspended school and university classes, set up quarantines and imposed social distancing measures. As the virus spreads, however, separate responses will fall far short in blunting the human and economic catastrophe widely expected in a country entering its sixth year of war with a failing health system and more than 80 percent of its 30 million people already relying on humanitarian assistance.[146]

The pandemic may require a lockdown, as has happened elsewhere, placing severe restrictions on people’s movement and posing a major disruption to their livelihoods. The internationally recognized government’s containment plan as submitted to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) includes that possibility, if needed.[147] However, this proposition has not been supported with a detailed plan on how the short-term economic impact of a lockdown can be mitigated. Anecdotal evidence has shown that even with partial curfews, economic activities in Yemen’s big cities have slowed down, and working people, especially small shop owners, daily laborers and street vendors, have been hit hardest so far. (See: ‘Yemenis Fear Starvation More Than COVID-19’.

It is essential to establish a joint fund to finance the policy responses to the pandemic. In order to show leadership and credibility toward their own people and the international community, both treasuries should be the first to finance such a fund and not wait for international grants that might take time to be disbursed. Public revenues from collected taxes and tariffs should be redirected toward financing the emergency fund. International and — most importantly — regional stakeholders have the moral obligation to support such a fund.

In the case of a lockdown, one must reckon with a sharp decrease in people’s disposable incomes. Along with the severe impact on livelihoods, food prices would significantly increase due to disruptions in market supply chains.[148] The Yemeni rial is projected to experience another wave of devaluation due to decreasing remittances.[149] Yemenis abroad, especially in neighboring Saudi Arabia, also face lockdowns that prevent them from working or sending cash back home across the border. These factors combined with a loss of government revenue from crude oil exports hit by falling global oil prices mean the Yemeni government’s fiscal deficit is projected to increase by 1.3 percent of GDP in 2020.[150] [151]

Given there is less room for implementing a monetary policy response at the moment, the focus should be on implementing short-term fiscal policies that will mitigate the impact of a lockdown. The emergency fund should provide cash assistance to people engaged in precarious labor and be used in part to increase medical facilities’ capacities.

The internationally recognized government has said it is planning to increase health sector spending to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 by 2 percent of GDP over the course of 2020, or about US$500 million.[152] In northern parts of Yemen under Houthi control, where 70 percent of the population lives, the de facto health authorities have warned they are far short of hospital beds, ventilators and test kits.[153]

Yemen’s working poor, who constitute a large share of the still-employed population after five years of war, should not be abandoned during the fight against COVID-19. A cash assistance program for the duration of a lockdown targeting those who lose their livelihoods would be a lifeline for informal and irregular workers, and small business owners. This can be built on the existing national cash assistance program of the government’s Social Welfare Fund, which was suspended early in the war but later funded by the World Bank and executed by UNICEF to provide cash assistance to families. Relaunching the program with funding from an emergency fund will be more efficient than designing a new direct cash transfer program.

In big cities such as Sana’a, Aden, Marib and Taiz — where roughly 6 million to 7 million people reside — it would be appropriate to implement a rent-freeze for the duration of the lockdown. Families allocating a larger share of their dwindling income to food purchases can be expected to come up short on rent money at the end of the month.

Undoubtedly, establishing such a fund will be challenging, but many countries in the region with a large share of informal and irregular workers, such as Egypt and Morocco, have established emergency funds or implemented such policies.[154] Jordan and Tunisia are implementing policies that go beyond providing direct cash transfers to the most vulnerable segments of the population and include tax exemptions for small businesses.[155]

A severe economic crisis will have immense humanitarian repercussions on the country’s working population, cutting what for many Yemenis is their final lifeline. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that the policy response is not politicized by the different warring parties and remains directed toward mitigating the devastating impact of COVID-19 on lives and livelihoods. The existential threat the novel coronavirus presents requires unprecedented courage, cooperation and pragmatism.

Amal Nasser is an economist with the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies who focuses on the political economy of Yemen.

Houthis Name New Central Bank Governor

On April 18 Houthi authorities announced the appointment of Hashem Ismail Ali as the new governor of the Sana’a-based Central Bank of Yemen (CBY).[156] Ali had been serving as an economic advisor to Mahdi al-Mashat, president of the Supreme Political Council, and was a Houthi-appointed board member of the Sana’a CBY. In 2018, he held the position of deputy finance minister. A longtime Houthi loyalist, in recent years Ali has been a key decision maker on economic and financial affairs for the Houthis, chairing the group’s economic committee and handling negotiations on the economic aspect of the Stockholm Agreement and the decrepit SAFER oil platform among other files.

This is the third Sana’a-based CBY governor appointed by the Houthis. Ali replaces Rasheed Abu Lahom, who returns to his former position as finance minister. At the time of his appointment in August 2019, senior banking officials told the Sana’a Center that Abu Lahom was considered a safe option for members of the Houthi leadership who had grown frustrated with the level of autonomy enjoyed by previous governor Mohammed al-Sayani. Following President Hadi’s decision to relocate the headquarters of the central bank to Aden in September 2016, then-deputy governor Al-Sayani began running operations at the Sana’a CBY. In October 2018, he was appointed governor by Houthi authorities, officially recognizing a role he had been playing for years.

Abu Lahom was dismissed as central bank governor in early March, more than a month before his successor’s appointment.

Major Drop in Remittances Forecast for Yemen

As COVID-19 measures shut down Saudi Arabia’s economy and oil prices collapsed, economists predicted in April that remittances to Yemen could drop by 70 percent in the coming months.[157] According to statistics from before the conflict, more than three-quarters of Yemenis working abroad were based in the kingdom.[158] A 2016 food security assessment by the UN found that 9 percent of Yemeni households depended on remittances as their main source of income.[159]

As a result of the conflict-driven suspension of hydrocarbon exports, previously the country’s largest source of foreign income, remittances became Yemen’s largest channel for foreign exchange entering the country. Totalling billions of dollars annually, remittances are the primary source of foreign currency in the local market and critical to facilitating imports of basic commodities. A 2019 paper by the Sana’a Center found that the survival of millions of Yemenis had become dependent on remittances sent home from relatives working Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere.[160]

Economic Developments in Brief:

- April 7: The vice governor of the central bank in Aden and the finance minister of the internationally-recognized government stated in a letter to the IMF the government’s intention to increase health sector spending by 2 percent of GDP throughout 2020 as part of the government’s COVID-19 containment plan.[161]

International Developments

Around the Region

Gulf States Battle COVID-19 and Falling Oil Prices

During April, Gulf states were confronted with the spread of COVID-19 and falling oil prices as global demand plummeted. Saudi Arabia continued to fight to defend its market share in an oil price war with Russia before the two countries agreed April 12 to the biggest production cuts in history.[162] The deal failed to immediately stem the fall in prices, with Brent Crude standing at US$20 per barrel at the time of writing.

How Gulf states will fare during this demand shock will depend much on their structural economic health and the degree of dependence on their oil sectors. The UAE’s relatively diversified economy puts it in a better position than most, though its non-oil sectors have been hit by COVID-19-related shutdowns with Dubai considered the most exposed of the Emirates due to its reliance on tourism and transportation.[163] Oman, which is already burdened with high levels of public debt and unemployment, will be particularly affected by the drop in prices.[164] The Sultanate relies on its oil and gas sector for 80 percent of its government revenue and has higher production costs per barrel compared to most of its neighbors.[165] Moreover, China buys the overwhelming majority of Oman’s oil, making its economic outlook heavily dependent on a rebound in Chinese demand.