On February 21, Saudi Arabia agreed to supply the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) in Aden with a US$1 billion deposit to prop up Yemen’s faltering economy and support the value of the rial in government-held areas. The aid will not be deposited directly with the CBY-Aden, but rather handled through the Arab Monetary Fund (AMF) as part of the AMF agreement announced in November. Access to the new money is expected to be granted soon given the progress the government has made to implement reforms demanded by Saudi Arabia, but the inflexible structure of the support could limit the central bank’s capacity to auction foreign currency to stabilize the rial and finance the import of basic commodities.

The timing of the Saudi deposit is fortunate. Public revenues have dropped substantially following the halting of oil exports after Houthi drone attacks on ports in Shabwa and Hadramawt last fall. More recently, the government has witnessed a loss of customs revenue as Houthi authorities have begun to pressure commercial importers to redirect goods from Aden to the port of Hudaydah. The shift could cost the government YR45-50 billion in monthly customs duties.

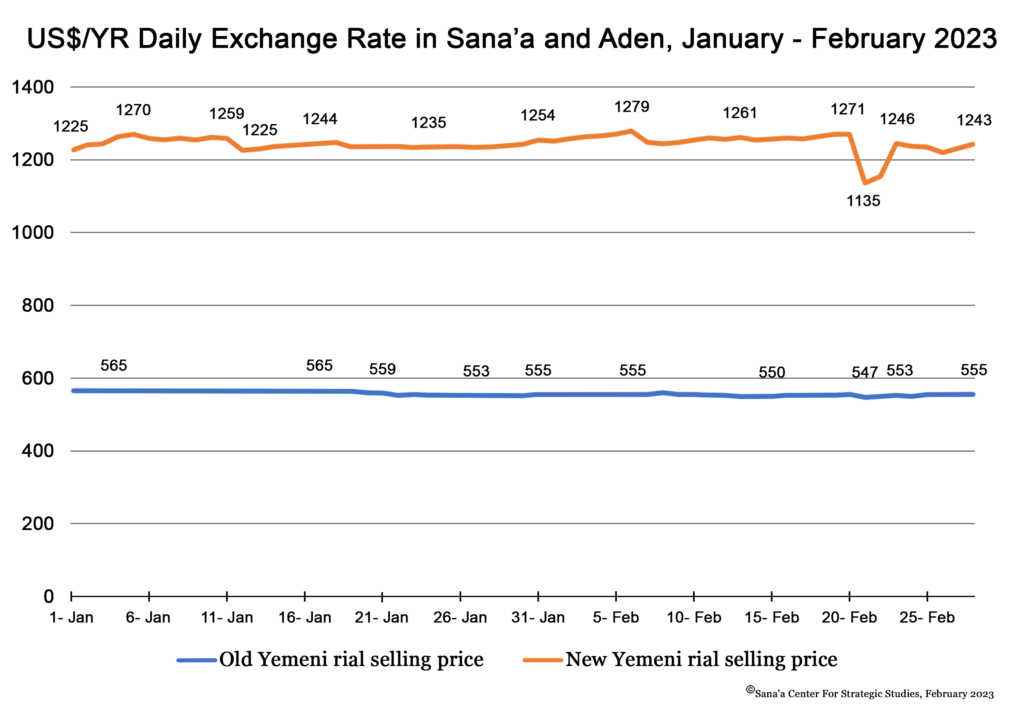

Currency

The Yemeni rial (YR) experienced slight fluctuations in both government- and Houthi-held areas in January and February. New rials in government-held areas depreciated by almost 4 percent, from YR1,225 per US$1 on January 1 to YR1,270 per US$1 as of February 19. They regained some value after the announcement of the new Saudi support, trading at YR1,243 by month’s end. Old rial banknotes circulating in Houthi-controlled areas fluctuated between YR540 and YR560 per US$1 during January, in reaction to news reports claiming progress in negotiations between Saudi Arabia and the Houthi movement. Old rials remained stable during February, trading at YR554 per US$1 on average.

The central bank in Aden held eight FX auctions over January and February, with US$280 million on offer. However, only US$104 million, 0r 40%, was purchased. The January 24 auction was the most undersubscribed of the year, and only 11 percent of the US$50 billion on offer was sold. The February 28 auction drew funds from the CBY-Aden’s account with the National Bank of Saudi Arabia. The central bank temporarily suspended the auctions in late February due to dwindling foreign currency reserves.

Limited participation coincided with an intensifying battle between the central bank branches in Aden and Sana’a over control of banking sector data. The former has attempted to regain unlimited access to Yemeni banks’ data records, while the latter has threatened increasingly restrictive measures to prevent compliance. In mid-January, the Houthi-run CBY-Sana’a issued a decree banning Yemeni banks and commercial traders headquartered in Sana’a from participating in the FX auctions or utilizing Letters of Credit under the CBY-Aden’s scheme, hampering demand for hard currency. Houthi authorities justified the move by saying that the auctions had resulted in the transfer of FX liquidity from areas under their control to government-controlled areas. Banks that have refused to share their data have been banned from participating in the currency auctions. Prior to the ban, Sana’a-based commercial traders purchased almost 60 percent of the FX offered via commercial banks.

CBYs Freeze Accounts of Money Exchangers

The rival central bank branches both issued circulars targeting money exchangers in an attempt to curb currency speculation. On January 26, the CBY-Aden froze the accounts of 17 money exchange shops that had been accused of currency speculation, and ordered other entities to cease doing business with them. Two days later, the Houthi-controlled CBY-Sana’a issued a circular targeting other money exchangers. By the end of January, dozens had had their accounts frozen and been cut off from conducting financial transactions. Bans have mainly targeted unlicensed money exchangers, persons, or companies that have conducted business with unlicensed firms, and individuals accused of speculating and manipulating the market over social media networks.

Unpaid Money Transfers

Transfers totaling billions of Yemeni rials (YR) and millions of Saudi riyals (SR) from money exchange outlets and hawala networks in Houthi-controlled areas have reportedly gone unpaid. At the end of January, a list containing 64,000 outstanding hawala transfers, amounting to more than YR2 billion and SR30 million, along with the names of beneficiaries, was leaked on social media. The leaked transfers were from the Al-Imtiaz network, one of the largest in Yemen, and are the result of beneficiaries having died or having not been notified of pending transfers.

On January 1, the CBY-Sana’a issued a memo demanding transfer networks commit to its Circular No. (6) of 2021. Similarly, the CBY-Aden called on money exchange outlets and money transfer networks to hand over detailed statements of all outstanding hawala transfers. The circular mandated that money transfer networks send text messages to beneficiaries every 30 days notifying them of uncollected transfers. It also provided a mechanism for senders to collect unclaimed transfers. However, most money transfer networks didn’t comply, instead accumulating rial liquidity and refusing to honor numerous hawala balances.

During February, several hawala networks announced their intention to honor billions of Yemeni rials in unpaid money transfers. On February 6, Al-Najm Financial Remittances Network, the biggest hawala network in the country, said that it had made it possible for beneficiaries to check on the status of unpaid transfers. Other hawala networks, including Al-Hazmi, Al-Imtiaz, Al-Bareq, Al-Akwaa Al-Amery, and Yemen Express, announced the launch of their remittance inquiry tool to enable beneficiaries to track and check outstanding transfers.

Outstanding transfers likely total in the tens of billions of Yemeni rials. A source in the money exchange market in Sana’a reported that there are at least another 80,000 transfers pending at the Al-Najm Network, amounting to billions of rials. The largest portion of outstanding transfers is owed to commercial traders and businessmen, who rely heavily on money exchange companies and hawala networks to facilitate business and carry out overseas trade. After outlets announced they would pay outstanding transfers, thousands of Yemeni citizens hurried to collect. While some have been able to claim their funds, many encountered difficulties. Some transfer networks sought to prevent payouts by intentionally letting their liquidity fall or putting in place arduous bureaucratic requirements.

The largest challenge is the lack of a unified money transfer network to settle payments. On February 3, the CBY-Aden announced the imminent launch of a network for financial transfers, involving 47 money exchange companies with total capital of YR5 billion. The network could bolster the CBY-Aden’s efforts to track transfers from banks, money exchangers, and hawalas, and mandate the deposit of funds at banks subject to CBY-Aden supervision and control.

Govt Custom and Fuel Increases Draw Wide Criticism

On January 10, the government’s Supreme Economic Committee issued three decrees, raising the custom exchange rate and the prices of locally produced fuel, electricity, and water. The first decree increased the customs tariff on imported goods by 50 percent, from 500 to 750 Yemeni rials (YR) per US$1, in all government-controlled areas. A second decree raised the price of locally refined petrol by almost 180 percent, from YR175 to YR487.5 per liter. The price for a 20-liter gas cylinder was raised by 43 percent, from YR2,100 to YR3,000.

The hikes came as the government suffers large fiscal deficits, compounded by the halt in oil exports. At the end of last year, the Presidential Leadership Council issued Resolution No. 30 of 2022, ordering the government and its Supreme Economic Council to adopt urgent measures to mitigate the current crisis, implement economic reforms, and develop state resources. A crisis cell was formed, headed by Prime Minister Maeen Abdelmalek Saeed. On January 16, the crisis cell attempted to assuage concern about the custom exchange rate increase, noting that the decision will not affect basic commodities such as wheat, rice, cooking oil, baby formula, and medicine, which are exempt from tariffs, and that the policy is primarily targeting luxury goods. However, given its limited capacity constraints, it is unlikely that the government will be able to contain the scope of price inflation.

The reform package was met with widespread criticism. Parties in and out of government denounced the measures and warned of their catastrophic effects. Speaker of Parliament Sultan al-Barakani criticized the proposed reforms, saying they failed to take into consideration people’s living conditions. The customs hike drew the most opposition. Several commercial traders and commodity importers ceased customs transactions and shipment clearances, opting instead to stockpile goods at Aden port and explore options for unloading the goods elsewhere. Other groups threatened non-compliance. On February 6, the Administrative Court in Aden suspended the government’s decision to raise the customs exchange rate.

Battle to Control Imports Intensifies

Following the government’s decision to raise the customs exchange rate, Houthi authorities offered economic enticements in a bid to steer imports to the Houthi-held port of Hudaydah, at the same time imposing punitive measures on merchants who import via Aden by preventing their cargoes from entering Houthi-controlled markets. In February, hundreds of commercial trucks carrying thousands of tons of various commodities were held at Houthi customs clearance centers at the entrances to Sana’a and Dhamar governorates.

Houthi authorities pressured commercial importers to provide written guarantees that they would no longer import goods through government-controlled ports and would direct them to the port of Hudaydah. On February 9, during a meeting with officials from the Houthi-run Ministry of Industry, merchants from the Sana’a-based Chamber of Commerce and Industry raised concerns that shipping companies would refuse to ship goods through Hudaydah or ask for high insurance fees. Houthi officials promised to provide an alternative shipping line. While some traders have folded to the Houthi pressure, others have been hesitant to do so. The Hayel Saeed Anaam Group, the largest business conglomerate in the country, has yet to commit, given the risk and cost associated with shipping to Hudaydah.

In reaction to Houthi pressure, Transport Minister Abdelsalem Humaid sought to reassure merchants following a joint meeting of the ministries of transport and trade and the Chamber of Industry in Aden on February 21. Humaid said that procedures for vessels entering Aden and other government-controlled ports had not changed. But he indicated that the government would soon pass new rules that limit foreign exchange support and insurance reductions to importers that brought in goods through its ports. On February 22, the government-run Gulf of Aden Ports Corporation issued a memorandum to the Hudaydah Shipping and Transports Company warning against the redirection of imported goods and threatening to blacklist shipping companies that acquiesce to Houthi demands.

On February 13, the head of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Aden, Abu Bakr Baabid, claimed that many commercial ships had changed course toward Hudaydah and warned of the negative consequences on the economy in government-controlled areas. Credible sources indicated have that restrictions previously imposed by the Saudi-led coalition have been recently eased, even though ships continue to be inspected by the United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen (UNVIM).

The move to increase import traffic comes in parallel with Houthi efforts to pressure the government and Saudi-led coalition to suspend UNVIM. The Houthi-affiliated Ministry of Industry reiterated its call for merchants to redirect imports to the port of Hudaydah and offered reduced customs duties of up to 50 percent. Merchants would pay custom tariffs only once if they redirected imports to the port of Hudaydah. Goods imported through Aden are currently subject to dual customs, first when they arrive, and again when they enter Houthi-controlled areas.

The rerouting of imports to Houthi-held ports would mobilize additional customs revenue for the Houthis while further harming government finances, which are already in a critical state. On February 23, the head of the government-run Central Bank of Yemen in Aden (CBY-Aden), Ahmed Ghaleb, indicated that the government could lose YR45- 50 billion in monthly customs duties should the Houthi gambit find success.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية