Marib governorate has emerged as a pivotal battleground between the armed Houthi movement on one hand, and the internationally recognized government and their respective allies on the other. The opposing forces are pressing with all of their might to achieve military victories in Marib, knowing that the outcome of the battle for the governorate holds the potential to decisively change the national balance of power.

In the early months of Yemen’s civil war, Marib emerged as a safe haven for internally displaced people (IDPs) fleeing Houthi-controlled areas. Marib’s small pre-war population of about 400,000 is estimated to have grown to between 1.5 million and 3 million people, with the bulk of the new arrivals settling in the capital, Marib city.[1] Amid this influx of IDPs, the internationally recognized government chose Marib as the headquarters for several departments in the Ministry of Defense, regional army commands formerly based in Houthi-held areas and training camps affiliated with these military units.[2] The Saudi-led coalition built army bases and installed Patriot missile defenses outside Marib city to protect oil infrastructure and support government forces, providing a security umbrella over the growing urban center, and thereby facilitating its growth.

After a four-year lull in fighting in Marib since late 2015, in January 2020, Houthi forces renewed their efforts to seize the governorate and have pursued this goal relentlessly. Since then, the frontlines in Marib have routinely been the bloodiest of the civil war.

The battle for Marib has attracted a growing number of military and security forces from outside the governorate. At the same time, political groups have sought to gain a foothold there. As part of broader strategies aimed at winning Marib, these outside actors have reshaped the local landscape in many ways, including through the installation or co-optation of tribal sheikhs who are more welcoming to their presence, and the appointment of loyalists in military, security and political institutions.

Identifying the most influential outside actors fighting for control of Marib and the strategies they are using to impose their will on the governorate is important to an understanding of how the socio-political landscape has changed during the war and what that means for the future.

While both Houthi and government forces have recruited Maribi locals to varying degrees, many of these individuals named to leadership positions do not wield as much power as their titles would indicate. Both warring parties have sought to highlight the presence of Marib locals on the frontlines and in decision-making roles to foster tribal and local legitimacy for their combat operations.[3]

After a brief overview of Marib’s pre-war indigenous population, this paper will identify the main military, security and political actors affiliated with the warring parties in Marib and describe how they are trying to reshape the governorate in their own image. The paper concludes by examining how Marib could change in the long term in the event of a decisive military victory by either of the warring parties.

Marib’s Indigenous Population

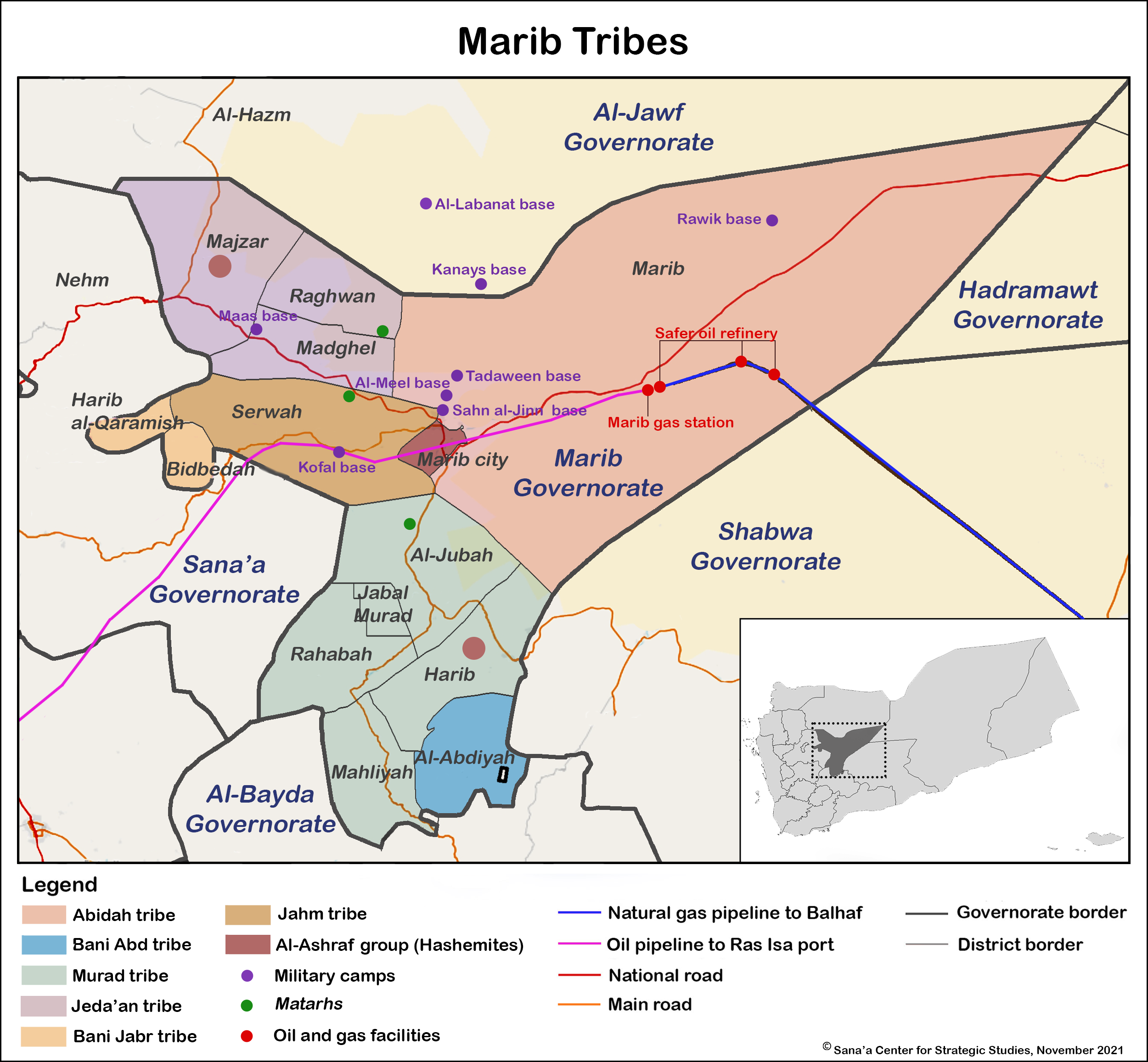

Generally speaking, Marib’s indigenous population is composed of five tribal groupings – the Abidah, Murad, Al-Jadaan, Bani Jabr and Bani Abd – whose rules and customs regulate society, politics and economic life in the absence of an effective state. The two largest and most powerful tribes are the Abidah and Murad.

Abidah tribal lands cover the eastern half of the governorate, where oil and gas fields and infrastructure are concentrated. Marib’s governor, Sultan al-Aradah, is from the Abidah tribe. Although the capacity of local governance has greatly expanded under Al-Aradah’s leadership and eased the burden on tribes to perform the functions of the state, tribal identity remains strong.

The Murad, which is the largest tribe in Marib in terms of numbers, has the second-largest geographical footprint, predominantly located in five districts in southwest Marib: Rahabah, Al-Jubah, Jabal Murad, Mahliyah and Harib. In recent decades, Murad tribesmen enjoyed a strong presence in government and military leadership positions, owing to the greater access to formal education in their tribal areas, which stemmed from the tribe’s affiliation with the ruling General People’s Congress (GPC) political party of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh.

Rather than invest in the development of a strong state presence in Marib, Saleh exercised influence in the governorate by co-opting influential tribal leaders to protect oil and gas pipelines and electric power lines, while rallying tribal fighters to weaken tribes that threatened the interests of the president. This tribal elite, which was for the most part affiliated with the GPC, benefited from the weakness of the state.[4]

In addition to Marib’s tribes, a network of families known as Al-Ashraf make up another important social group in the governorate. Concentrated in Marib city and in some parts of Harib and Majzar districts, the Al-Ashraf are Hashemites, or descendants of the Prophet Mohammed. Unlike the Zaidi Shia Hashemites prevalent in the Houthi-held highlands in northwest Yemen, the Al-Ashraf in Marib follow the Shafei branch of Sunni Islam. The vast majority of tribespeople in Marib are also Shafei Sunnis, while most of those in the neighboring highlands are Zaidi Shia. Historically, sectarian differences have not been a significant factor in conflicts between Marib’s inhabitants. Tribal disputes over land and access to resources have been a more common source of conflict.[5]

Government Military, Security and Political Forces in Marib

When Houthi forces seized the capital Sana’a in September 2014, Marib’s tribes formed a fighting force known as the ‘popular resistance’ in anticipation of Houthi incursions into the governorate. These resistance forces found a willing military partner in the internationally recognized government, which, after being driven out of Sana’a, quickly transformed Marib into its de facto capital in the north and military hub from which it could launch operations against the Houthis.

The Islah party, which has a great deal of influence in the internationally recognized government, also established Marib as a base after losing its presence in most northern governorates when the Houthis swept to power. The relative stability in Marib attracted a number of middle-ranking and lower-ranking Islah party leaders to the governorate.[6] As the war has dragged on, Marib has continued to be a destination for other Islah officials and supporters, such as those driven out of parts of southern governorates as the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) has consolidated control of Aden and surrounding areas.[7]

Although Islah had a presence in Marib before the war,[8] Saleh’s GPC party dominated the governorate’s political landscape. Support for the GPC, however, began to decrease across Marib after Saleh’s ouster in 2012 following Yemen’s 2011 Arab uprisings. This decline in support accelerated after Saleh allied with the Houthis to take over Sana’a in September 2014 and expand militarily across the country. In 2014, the Marib branch of the GPC, led by Murad tribal leaders Abdulwahid al-Qabli and his father, Ali Nimran al-Qabli, rejected a request from Saleh to remain neutral and not fight the Houthis.

The subsequent deaths of several prominent GPC leaders, including Saleh, who was killed by the Houthis in December 2017, have further eroded GPC support in Marib. Some of these former Saleh loyalists, such as Al-Qablis, established a GPC wing aligned with President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, while others shifted their support to the Islah party, which has used its powerful presence in the Hadi government and presence on the ground to capitalize on these shifting political winds. For example, Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, who is technically registered as a GPC member, but has long supported Islah, has been the top government official overseeing military operations in Marib since 2016. Saudi Arabia has also attempted to co-opt a number of senior GPC figures during the war.[9]

Marib’s Abidah tribe has, indeed, become a center of gravity of the Islah party during the war. Abidah areas historically voted for the GPC in parliamentary elections. A number of prominent Abidah tribesmen, including Governor Al-Aradah, who was formerly a member of the GPC Standing Committee and a Member of Parliament with the party, have gravitated toward Islah in recent years. This shift has been based more on pragmatism than ideology, as Islah has emerged as a dominant power in Marib with ample resources. These stem in large part from the party’s close relationship with the central government and Saudi Arabia.

While tribal identity remains stronger than party affiliation or other factors, the Islah party has been relatively successful in partnering with Marib locals. This alliance is primarily rooted in the common goal of preventing Houthi incursions into the governorate, but is strengthened by a shared adherence to Shafei Sunni Islam, which has a long history of opposition to inroads by the Zaidi Shia groups that ruled parts of northwest Yemen, on and off, over the last millennium.

However, Islah’s relations with Marib’s locals have been strained at times by the party’s appointment of unqualified loyalists to military, security and public administration positions. A frequent complaint from political leaders and social figures who are not affiliated with the Islah party is the presence of a large number of teachers affiliated with the group, who previously worked in public schools, Quran memorization schools or the education ministry, in civil and military institutions.[10]

Islah has directly supported Marib sheikhs who are perceived as loyalists at the expense of sheikhs aligned with other political parties, such as the GPC and the Yemeni Socialist and Nasserist parties.[11] Individuals from these parties also accuse Islah of installing loyalist military and security leaders from outside Marib over those from the local population.[12] Some GPC figures and sheikhs who were influential before the war, when Islah and the GPC were competing intensely in local and parliamentary elections, say they have since been marginalized.[13] Members of the Islah party have also gained a large presence in business and real estate activities in Marib city’s booming economy.[14] The party’s widespread influence within the governorate has led many Marib residents to engage with Islah on a pragmatic basis in order to advance their own interests.[15]

As the governor and one of the Abidah tribe’s most respected leaders, Al-Aradah has played a crucial role in managing relations between Marib’s indigenous population and power brokers like the Islah party, as the governorate grew into a major government stronghold during the war.[16] Al-Aradah was selected as the ultimate arbitrator of tribal disputes on September 18, 2014,[17] when Marib’s tribes agreed to postpone feuds in order to focus on protecting the governorate from Houthi advances. They agreed that Al-Aradah, in his capacity as an Abidah tribal sheikh and Marib governor, would mediate any future disputes. The agreement helped define the balance of power between the governorate’s tribes and the state, in this case mostly meaning the Islah party.[18]

Houthi Forces in Marib

The majority of Houthi commanders overseeing the Marib fighting hail from the group’s northern stronghold in Sa’ada governorate along the Saudi border. Most of these commanders fought during the six Sa’ada wars between 2004 and 2010 in which Houthi forces variously battled army forces loyal to Saleh, and military units loyal to General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar. Some of the most senior Houthi commanders in the Marib campaign are related to Houthi leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi. These include his brother, Abdelkhaleq al-Houthi (Abu Younes),[19] commander of the Central Military Region, which includes Marib. Yusuf al-Madani,[20] who leads Houthi forces in Hudaydah, Hajjah, Mahwit and Raymah governorates as commander of the Fifth Military Region, was recently assigned to the offensive in Marib. He is married to one of the daughters of the Houthi founder, Hussein Badreddine al-Houthi, another brother of Abdelmalek. The Houthis’ security supervisor in Marib also hails from Sa’ada. Only a handful of Houthi military and security leaders in Marib are from the governorate, such as Mubarak al-Mishn al-Zayadi, commander of the Third Military Region, which covers Marib and Shabwa governorates.[21] However, Al-Zayadi’s duties are limited to formal inspection visits, meaning that in practice, he does not exercise substantial influence.[22] The power is thus concentrated in the hands of Houthi leaders from outside the governorate, such as Abdelkhaleq al-Houthi and Yusuf al-Madani.

Most of the rank-and-file Houthi forces fighting in Marib come from Amran, Sana’a and Dhamar governorates.[23] The small numbers of Houthi forces from Marib are mainly from the Hashemite Al-Ashraf group or the Zaidi minority of the Bani Jabr tribe and its Jahm subtribe in Harib al-Qaramish district.[24] In addition, a few figures from the Murad tribe, such as the prominent sheikh Hussein Hazeb, along with a few other minor tribal leaders, sided with the Houthis for political and other reasons unrelated to religion.[25]

The Houthis have struggled to recruit Marib locals to their cause for a number of reasons. The vast majority of people in Marib follow the Shafei branch of Sunni Islam, including the Al-Ashraf group. The Houthis’ divisive sectarian rhetoric during the war has exacerbated distrust between Shafei and Zaidi communities. From a tribal perspective, Marib locals have cited the Houthis’ double-dealings with the tribes that facilitated their entry into areas in Amran, Hajjah, Sana’a and other Houthi-controlled governorates as evidence that the group does not respect tribal norms and cannot be trusted. Indeed, the Houthis regard tribes as inferior to the Hashemite sayyid class to which the Houthi family belongs. The Houthis, like the Zaidi Hashemite dynasties that ruled parts of Yemen on and off for a millennium, have strategically manipulated tribal norms in order to gain religious and political legitimacy, while also relying on the tribes to supply fighters.[26]

There are also deep historical rifts between populations in Marib and Sa’ada governorate, which is a traditional Zaidi stronghold and the Houthi movement’s homeland. Starting in the 1930s, Marib’s two dominant tribes, Abidah and Murad, fought back military incursions by the Zaidi imams of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen. In 1948, Sheikh Ali Nasser al-Qardae’i, one of the most prominent sheikhs of the Murad tribe, assassinated Imam Yahya Hamid el-Din, ruler of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom. It is widely believed in Marib that the Houthis seek to build a theocratic state modeled on the Zaidi imamates that were first based in Sa’ada, and later controlled larger areas of northern Yemen.[27]

Changing Tribal Dynamics

Like Saleh before them, Houthi and government forces have tried to coerce and co-opt local tribal leaders to control Marib. The warring parties have recruited a new class of sheikhs who are more welcoming of their presence and objectives. This has led to a rebalancing of tribal power in the governorate reminiscent of former President Saleh’s patronage politics.

Throughout the war, the Houthis have sought to empower loyalist sheikhs in areas where the group has geographical and cultural ties with local tribes.[28] The Houthi movement used this tactic in its six wars against the Saleh regime between 2004 and 2010, and has subsequently relied on it to consolidate power when it started expanding beyond Sa’ada governorate in 2011. Houthi inroads into other parts of Yemen greatly benefited from the group’s alliance with Saleh, whose tribal loyalists facilitated Houthi advances that culminated in the takeover of Sana’a in September 2014.

The Islah-dominated internationally recognized government has used similar tactics in Marib during the war. Some sheikhs affiliated with the GPC who benefitted from Saleh’s patronage system have been neglected, or their powers reduced, as resources have been diverted to new sheikhs.[29] Often, the newly-favored sheikhs work alongside the traditional sheikhs, but with financial and official support, their authority becomes dominant over time.

What’s Holding Marib Together? How Long Will it Last?

The outcomes of the battle for Marib will change many of the parameters of the current political equation, whether in the event of a forcible Houthi takeover of the governorate, or if government forces stem recent Houthi advances – or even if an accommodation is reached.

As the internationally recognized government’s last stronghold in northern Yemen and a source of abundant oil and gas reserves, Marib is a strategic and highly prized governorate in the war between the Houthis and the government.

Marib is also unique in that the diverse grouping of anti-Houthi forces there have not turned on each other, as witnessed in other major cities in non-Houthi controlled areas, such as Aden[30] and Taiz.[31] This is largely due to the fact they have set aside differences to focus on the urgent need to fight the common Houthi enemy. Another factor is Marib’s relative economic prosperity in recent years, which has helped diminish a key source of grievances in other governorates nominally controlled by the internationally recognized government. However, the growing power of the Islah party has strained these relations.

The outsize role of Al-Aradah in managing relations between local tribes and outside forces cannot be overstated; if something were to happen to the governor, the stability of Marib would be at great risk. Since the UAE removed its Patriot missile defense system from Marib in 2019, the Houthis have launched missile strikes numerous times against his homes – including his official residence in a government complex – most recently on September 26.[32] If the Houthi offensive is neutralized and the common enemy uniting Marib’s anti-Houthi alliance fades away, existing tribal feuds and tensions from new imbalances in power may emerge, if figures with the standing and respect of Al-Aradah are not in power to address them.

Rapid Houthi military advances in Marib’s southern Al-Abdiyah, Harib, Al-Jubah and Jabal Murad districts since late September have also now created a potential opening for them to attack Marib city from the south. A Houthi victory in Marib would usher in profound tribal, religious and cultural changes. As has occurred in other Houthi-controlled governorates, the group would appoint loyalists as supervisors (mushrifeen)[33] and to other key positions of power. New religious leaders, promoting an extreme version of Zaidi Shiism, would also be appointed. Indeed, after Houthi forces seized control of Harib district in Marib and Bayhan district in Shabwa in September 2021, the group immediately replaced the imams of mosques in these areas with extremist loyalists from Sana’a, Amran and Sa’ada governorates and started preaching in schools.[34] One of the major roles of the religious leaders is to conduct cultural lectures and summer camps aimed at indoctrinating children and other populations in Houthi-held areas.[35]

In the event of a Houthi takeover, Marib tribes, for their part, would likely resume sabotaging power lines leading to Sana’a, as they did at various times prior to the war as a means of leverage over the Saleh and Hadi governments. However, the tribes do not consider the Houthis to be a legitimate government and would likely not attack the pipelines simply as a tool for concessions, but more likely as part of an insurgency and a tactic to weaken Houthi power.

Even in the event of a Houthi takeover of Marib, the victory could therefore be pyrrhic. Local tribesmen share a deep cultural memory that considers Zaidi Hashemite groups like the Houthis to be outsiders seeking to dominate and subjugate them, rather than incorporate them into the ruling system.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

This publication was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies as part of the Leveraging Innovative Technology for Ceasefire Monitoring, Civilian Protection and Accountability in Yemen project. It is funded by the German Federal Government, the Government of Canada and the European Union.

Endnotes

- “Marib Urban Profile: a precarious model of peaceful co-existence under threat,” UN Habitat, March 2021, p. 21, https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2021/04/210408_marib_small.pdf

- The headquarters of the Third Military Region, which is responsible for operations in Marib and Shabwa governorates, is based in Marib. Temporary headquarters of the Seventh Military Region – which covers the Houthi-controlled governorates of Sana’a, Dhamar, Ibb and Al-Bayda – and the Sixth Military Region – which covers operations in Houthi-held Al-Jawf, Amran and Sa’ada governorates – are also located in Marib.

- Interview with a Murad tribal leader in Marib, November 2019.

- Casey Coombs and Ali Al-Sakani, “Marib: A Yemeni Government Stronghold Increasingly Vulnerable to Houthi Advances,” Sana’a Center For Strategic Studies, October 22, 2020,

- Interview with former Marib governor, Major General Ahmed Qarhash, November 2019.

- Ahmed Al-Tars Al-Arami, “Tribes and the state in Marib,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, May 4, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/13901

- Interview with an Aden-based Islah party official, August 2019. The official said that of the Islah leaders who fled Aden, some went to Marib, some to Turkey and some to Saudi Arabia, in response to the assassinations of Islah-affiliated preachers and imams in the interim capital and particularly after the STC took control of Aden in August 2019.

- Ibid. The Islah party’s relations with Maribi tribes date back to its formation in the 1990s, though its presence then was largely limited to Marib al-Wadi and parts of Harib, Al-Abdiyah and Al-Jubah districts; Islah remained in the shadow of former President Saleh’s more popular General People’s Congress (GPC) party.

- Interview with Marib-based researcher, October 2021.

- Interview with Marib-based researchers, August and October, 2021.

- Interviews with non-Islah political party leaders in Marib, November 2019.

- Ibid; interviews with two Murad tribesmen, one of them affiliated with the GPC, August 2020. Examples of senior military officials based in Marib who hail from outside the governorate include: Third Military Region commander Major General Mansour Thawabah from Al-Jawf governorate; Chief of Staff of the Third Military Region Brigadier General Abdulraqib Dibwan from Taiz governorate; former Marib Police Chief Abdelmalek al-Madani from Hajjah governorate; and former head of the Special Security Forces Abu Mohammed Shaalan from Hajjah.

- Casey Coombs and Ali Al-Sakani, “Marib: A Yemeni Government Stronghold Increasingly Vulnerable to Houthi Advances,” Sana’a Center For Strategic Studies, October 22, 2020,

- Interview with an Islah-affiliated businessman from Ibb governorate involved in real estate in Marib, January 2021.

- Interviews with seven Marib residents, June 2021.

- Al-Aradah’s brother, Khaled, who is close to Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, was sanctioned by the US Treasury Department in May 2017 for providing support to Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. Designation available here: https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/sm0091.aspx. Governor Al-Aradah has said the designation was politically motivated. See Ben Hubbard, “As Yemen Crumbles, One Town Is an Island of Relative Calm,” New York Times, November 7, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/09/world/middleeast/yemen-marib-war-ice-cream.html

- Naji al-Hunaishi, “Marib Commemorates the Third Anniversary of the Matareh Against Houthi Aggression [AR],” 26 September, September 20, 2017, http://www.26sepnews.net/2017/09/20/1-86/

- Ahmed Al-Tars Al-Arami, “Tribes and the state in Marib,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, May 4, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/13901

- The UN Security Council sanctioned Abu Younes in November 2014. Designation available here: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/2140/materials/summaries/individual/abd-al-khaliq-al-houthi; Recently, Abu Younes was replaced by Mohammad Abdulkarim al-Ghamari as Commander in Chief of the Houthi offensive in Marib, according to the US Treasury Department, which sanctioned Al-Ghamari in May 2021. Designation available here: https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USTREAS/bulletins/2da44c2/

- Al-Madani was sanctioned by the US Treasury Department alongside Al-Ghamari in May 2021. Designation available here: https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USTREAS/bulletins/2da44c2/

- Of the 24 Houthi military and security officials the Sana’a Center has identified in the Marib conflict, only five are from Marib.

- Interview with a Marib-based researcher, June 2021.

- Ibid.

- Bani Jabr and Jahm tribes are located in Serwah, Harib Al-Qaramish and Bidbedah districts, while the Al-Ashraf presence is concentrated in Marib city and in some parts of Harib and Majzar districts.

- Interview with a Marib-based researcher, October 3, 2021.

- Ahmed Al-Tars Al-Arami, “The Houthis: Between Politics, Tribe and Doctrine,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, September 2, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/ar/publications-all/analysis-ar/8003

- Interviews with Marib residents between November 2019 and October 2021.

- Interview with Marib-based researcher, June 2021.

- Interviews with non-GPC political party leaders in Marib, November 2019.

- Khaled Ameen, “Yemen’s Power-Sharing Cabinet: What’s at Stake?” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, April 5, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/13695

- Khaled Farouq, “Taiz: A Hotbed of Irregular Militias,” Sana’a Center For Strategic Studies, September 14, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/15055

- “Ballistic missile hit Yemen’s Marib governor house, Houthi rebels blamed,” Xinhua, July 5, 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-07/05/c_138199617.htm; “Yemeni gov’t says Houthis bombed Marib governor’s house,” Debriefer, September 28, 2021, https://debriefer.net/en/news-27140.html

- Recruited based on loyalty rather than qualifications, mushrifeen act as a parallel system of governance that supervises the various institutions and geographical areas under Houthi control. Mushrifeen are effectively immune from legal repercussions in the course of carrying out their work.

- Interview with Marib-based researcher, October 2021. “Watch the Houthi cry inside one of the Baihan mosques,” Facebook post, September 24, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/100038440412822/videos/3938941372875190/; “Armed elements of the Houthi militia stormed Bayhan High School,” Facebook post, September 28, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/100006564337241/videos/1613959895601735/; “Houthi militias stormed several schools in Bayhan district, forcing the students to shout and inciting them to hate and killing, and recruiting them into their ranks to fight against the sons of the south and the sons of Shabwa,” Facebook post, September 29, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/100016701246572/videos/444759257223804/

- See Salam al-Harbi, “How the Houthis Seized and Remade the Education System,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 13, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/15218#Houthi_remake_education_system; Manal Ghanam, “Curriculum Changes to Mold the Jihadis of Tomorrow,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, October 13, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/the-yemen-review/15218#Curriculum_changes

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية