When Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri was killed by a US drone strike in Afghanistan last July it had only limited impact for the group’s Middle East branches in North Africa, Yemen, and Somalia. This was in part a result of the internal cohesion created by organizational policies introduced since 2011 that gave regional branches significant autonomy. But it also spoke to Al-Zawahiri’s reduced importance as a leader in recent years as he took on more of a symbolic role as the successor to Osama bin Laden who had obtained the allegiance of Al-Qaeda’s central Shura council.

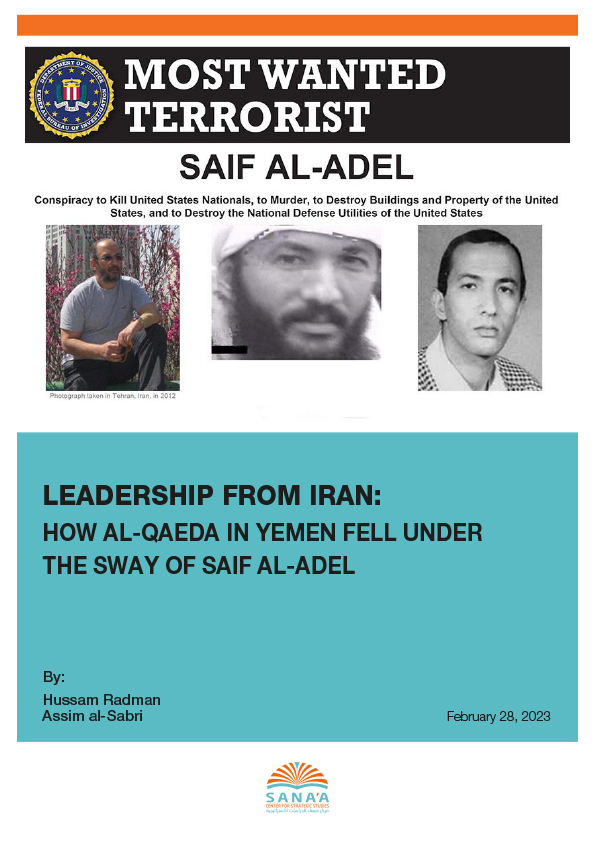

One of the key reasons why leadership on all the key fronts – security, organizational, and financial – shifted away from Al-Zawahiri was the strident claims on those spheres made by the group’s second-in-command, Mohammed Salah al-Din Zaidan, also known by the nom de guerre Saif al-Adel. From his home in Iran, Saif al-Adel has been particularly effective in taking over management of operations by the group’s branches in Syria, Yemen, and Somalia. Now the veteran Egyptian jihadist is betting on the Yemeni branch – commonly known as Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) – decisively tipping the internal balance of power in his favor so that he can officially assume leadership of the global Al-Qaeda movement, a position that remains vacant. A UN report issued this February assessed that Saif al-Adel is now de facto leader, a view supported by the US State Department – though Al-Qaeda has yet even to acknowledge the death of Al-Zawahiri.[1] Iranian officials reiterated denials that Saif al-Adel is in Iran.[2]

This paper will address three main issues. The first is the nature of the historical relationship between Al-Qaeda’s center in Afghanistan and its active branch in Yemen during the reign of Bin Laden and Al-Zawahiri. Secondly, it will examine the details surrounding the hidden role played by Saif al-Adel in Yemen, and how he has been able to build up influence, reaching a peak since Khalid Batarfi became leader in 2020. Finally, the paper will analyze the implications of Saif al-Adel’s increased influence, how it will impact Al-Qaeda in Yemen, and his chances of becoming the official agreed-upon successor to Al-Zawahiri.

The paper is based on analysis, information, documents, and data collected from three sources: Published research and journalism on Al-Qaeda; Al-Qaeda publications, including the Abbottabad documents; and information obtained from sources inside the group, including active and formerly active members inside and outside Yemen. It also relies on Yemeni sources whose close knowledge of AQAP activity means they were able to confirm many points and provide further information, including officials and tribal figures.

Part One: The Relationship Between the Central Leadership and the Yemeni Branch

Bin Laden and Al-Wuhayshi: A Father-Son Relationship (2006-2011)

In the mid-1990s, Osama bin Laden took the decision to return to Afghanistan to lead a jihad against the West. There, Bin Laden chose a Yemeni as his personal assistant, Nasser al-Wuhayshi, giving him the nom de guerre Abu Baseer. Al-Wuhayshi was Bin Laden’s loyal companion, continually present by his side until he was forced to flee to Iran after ensuring Bin Laden was safe in a fortified hiding place in the Tora Bora mountain range. Al-Wuhayshi slipped into Sunni areas of Iran until he was eventually captured by security services there.[3] In 2003, the Iranians handed him over to the Yemeni government, which held him in a prison run by the Political Security Organization, then the country’s top intelligence branch, in Sana’a. While incarcerated Al-Wuhayshi was able to organize his comrades and win their allegiance as emir (leader) in 2004. Two years later he would escape, allowing him to start building a jihadist movement in Yemen and lead it during its golden years.[4]

Following communications with the Al-Qaeda headquarters in Afghanistan, Al-Wuhayshi announced the formation of what he first called Al-Qaeda in the Southern Arabian Peninsula in 2007. Bin Laden formally supported Al-Wuhayshi’s move and in 2009 he also approved the plan to merge the Saudi and Yemeni branches of Al-Qaeda into a single organizational unit under Al-Wuhayshi’s leadership, adopting the name Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).[5] From the outset, the Yemeni branch enjoyed a special position in Bin Laden’s affections, as the letters found at his Abbottabad residence show. Following Al-Qaeda’s theory of jihad against the “distant enemy”, Bin Laden was keen to communicate to Al-Wuhayshi details of his strategic vision for concentrating on “the greater external enemy before the internal one” – meaning the United States and other Western powers before Muslim rulers – and to encourage AQAP to take a central role in those operations.[6]

Based on his own experience of Yemen, Bin Laden advised focusing on establishing a presence in the southern governorates, particularly Abyan and Shabwa as strategic locations with access to the sea and isolated rural areas. He also recommended investing in the popular unrest in southern Yemen against the regime of president Ali Abdullah Saleh and taking steps to counter the secessionist Southern Movement, which Bin Laden considered an extension of the leftist movements that had dominated the south since independence from Britain in 1967 and directed his supporters to fight during the 1994 civil war, providing them with funds. In northern Yemen, he stressed the importance of accommodating Yemeni tribes and drawing on them for support. Bin Laden initially wanted to avoid a direct military confrontation with the Sana’a government but later agreed on opening limited military fronts in Abyan and Marib in 2010-11 at Al-Wuhayshi’s insistence on condition that communications remained open to give both sides the option of a truce.[7]

In light of the increased mobilization of the Southern Movement in Yemen, in 2010 Bin Laden advised appointing a jihadist from southern Yemen to the group’s leadership. Al-Wuhayshi responded by nominating the charismatic Yemeni-American religious scholar Anwar al-Awlaqi and proposed that allegiance be given to Al-Awlaqi as the leader of AQAP. But Bin Laden resisted the idea, asking Al-Wuhayshi to remain in his position as the most deserving of the post of emir and requested more detailed information on why Al-Awlaqi should rise to a leadership position.[8] At a later date, Bin Laden told Al-Wuhayshi he should be more careful since Western media outlets were now describing Al-Awlaqi as AQAP’s leader, and passed on his suspicions that the US might be spying on Al-Awlaqi’s communications.[9]

Bin Laden was protective of AQAP for good reason – in a short time it had been able to establish an effective presence. In 2010, US intelligence classified AQAP as the most dangerous of all Al-Qaeda branches.[10] Months before US forces managed to kill Osama bin Laden in May 2011, the group’s leadership in Yemen started to use a more flexible and expansionist approach that aimed to take advantage of the security vacuum caused by the Arab Spring uprising. Al-Qaeda’s leadership during this period tried to ride the wave of popular protests against the Saleh regime and capitalize on the rise of Islamists to prominence across the region to achieve two objectives: to create political alliances with new government forces in Yemen – led by the Islamist Islah Party – to make the state less hostile to jihadist activity; and to use the collapse of state institutions to establish safe havens for Al-Qaeda in the southern and eastern governorates.[11]

Al-Zawahiri and Al-Wuhayshi: The Emir and His Deputy (2011-2015)

After Bin Laden’s death, the Yemen branch played a decisive role in the transfer of power to Al-Zawahiri. In July 2011, Al-Wuhayshi was the first jihadi leader to pledge allegiance, strengthening the bond between the two.[12] Al-Zawahiri gave the group’s leadership in Yemen his consent to extend its writ into towns in Abyan and rural areas in Shabwa, Al-Bayda, Marib, and Hadramawt via local operatives known organizationally as Ansar al-Sharia and to conduct broader military operations against Yemeni forces. When the Houthi movement seized control of Sana’a in 2014, Al-Zawahiri left the decision on whether to cooperate with the Saudi-led coalition against the Houthis to the Yemeni leadership, as well as the decision to establish an AQAP presence in major cities like Aden, Mukalla, and Taiz during security vacuum created early in the conflict.[13]

Al-Wuhayshi was able to rise quickly within the ranks of the general leadership of Al-Qaeda for two reasons. One was his close personal relationship with Al-Zawahiri went back to the days when both were constant companions of Bin Laden in Afghanistan. Secondly, he was able to fill a leadership vacuum following the killing of Osama bin Laden, since Al-Qaeda’s general coordinator Jamal al-Misrati (also known by the nom de guerre Atiyyat Allah al-Libi) had also been killed, and the general coordinator for regional branches Younis al-Mauritani was detained in 2011, while Saif al-Adel remained under house arrest in Iran.[14] So Al-Zawahiri appointed Al-Wuhayshi as the group’s First Deputy and began preparing him as his own successor.

To that end, Al-Zawahiri gave Al-Wuhayshi three regional tasks that exceeded his Arabian Peninsula remit, and Al-Wuhayshi succeeded in two while failing in the third. The first, in 2011, was to transform Yemen into a supply base providing fighters, funding, and arms to the jihadist movement in Syria as the country began its descent into civil war. The second, in 2012, was to manage and provide financial support for the Al-Qaeda branch in Somalia, whose formal name was the Youth Mujahidin Movement, aka Al-Shabaab.[15]

The third, and more difficult task, was given to Al-Wuhayshi in 2014. As Al-Qaeda’s First Deputy, he was asked to step in and mediate growing disputes among jihadist groups – particularly, the conflict between the Islamic State group, which operated in Syria and Iraq, and Al-Qaeda’s Nusra Front, which operated in Syria. When Al-Wuhayshi died the following year he had not been able to move forward on this issue.

His death in a US drone strike in June 2015 dealt a blow to Al-Qaeda after a long period of successful expansion globally, but it was particularly consequential for AQAP since it then came under the leadership of Qassim al-Raymi. The Yemeni branch became more focused on internal problems and its status began to fade as a vanguard of the group’s global struggle. More importantly, Al-Wuhayshi’s killing also contributed to strengthening relations between Al-Qaeda in Yemen and the jihadist leaders residing in Iran.

Part Two: The Influence of Saif al-Adel in Yemen

Saif al-Adel: Operating from Iran

Mohammed Salah al-Din Zaidan, a former Egyptian military officer and explosives expert, was one of the so-called Arab Afghans who had fought with the Mujahideen against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and an early aide to Bin Laden. Better known as Saif al-Adel, his leadership role grew in the mid-1990s, as he became head of Al-Qaeda’s Security Committee and a supervisor of the group’s external operations. He was a member of the inner circle that was briefed on the planned September 11 attacks on New York and Washington in 2001, though the US government believes he was among the senior figures who opposed the operation.[16]

Saif al-Adel traveled between Afghanistan and Iran during the late 1990s, enabling him to develop a relationship with security officers in Tehran. After the US invasion of Afghanistan, Saif al-Adel was responsible for receiving jihadist leaders in Iran and arranging their stay there. In 2002 this became a formal agreement with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) to provide safe haven for jihadist leaders in Iranian territory in return for coordinating efforts to target the United States, which invaded Iraq in March 2003.[17] The Iranian side quickly backed out after immense pressure from the US and Saudi Arabia, detaining a large number of senior jihadist figures, including Al-Wuhayshi, who was handed over to Yemen, and Saif al-Adel, who was kept under house arrest while receiving special treatment.

From there, Saif al-Adel was able to organize a number of external operations, including the May 2003 bombings in Riyadh,[18]although being trapped in Iran meant he had little opportunity to rise within the ranks of Al-Qaeda while younger figures from Yemen and North Africa became prominent, taking on leading roles. In 2008, Saif al-Adel began to provide some advice to Al-Qaeda’s leadership in Yemen, especially with regard to external operations. Al-Wuhayshi consulted him on operations launched by Al-Qaeda’s branch in Yemen such as the 2009 assassination attempt against Saudi Deputy Interior Minister Prince Mohammed bin Nayef, and the botched bombing of a US passenger plane later the same year when explosives hidden in the underwear of Nigerian jihadist Omar Farouq Abdulmuttalib failed to detonate.[19]

At the time, Al-Wuhayshi and Bin Laden had a shared assessment that Saif al-Adl was not a suitable candidate for a larger role in the general leadership of the group, despite his skill in organizing attacks. This was likely because Saif al-Adel was in Iran and seen as too close to IRGC chief Qassem Soleimani, as well as the fact that he had previously disobeyed bin Laden’s directives on several occasions.[20] Overall, Bin Laden was preparing the ground for a transfer of power to the second generation of jihadists and leaned toward promoting Al-Wuhayshi more than members of the old guard who had fought with him against the Soviet Union, foremost among them Saif al-Adel.[21]

Saif al-Adel Chooses to Stay in Iran Despite Deal to Release Him

Between 2010 and 2011, Iran allowed Bin Laden’s family, who were also stuck in Iran, to leave for Afghanistan under a negotiated agreement. Al-Qaeda would release Iranian diplomat Heshmat Allah Zadeh (who was kidnapped in northern Pakistan in the winter of 2008) in exchange for the release of Iran-held Al-Qaeda operatives, including Bin Laden’s favorite son Hamza and his mother Khairiyya Saber, in addition to two other sons, Osman and Mohammed, who were later released.[22] After the bitter sectarian violence in Iraq during the early years of the US occupation and growing signs of an uprising against its Syrian ally in 2011, Iran was hoping to neutralize the threat of Sunni jihadism and redirect it toward Western interests. However, the death of Bin Laden – who had supported that strategy – quickly led to renewed tension between Iran and Sunni jihadist groups. AQAP then began to look for new means to pressure Tehran into releasing the Al-Qaeda leaders still in its custody.

It was Al-Wuhayshi’s idea – with Al-Zawahiri’s approval – to kidnap the Iranian cultural attaché in Sana’a, Noor Ahmad Nikbakht, in 2013. The two sides negotiated for two years, leading to a prisoner exchange in March 2015. The deal called for Iran to release five senior Al-Qaeda figures, including Saif al-Adel, in exchange for AQAP releasing the Iranian diplomat.[23]But when the Al-Qaeda members arrived in the border region by Afghanistan, Saif al-Adel surprisingly announced that he preferred to stay in Iran and had secured Iranian support for ongoing operations against Western interests.[24] This included granting him freedom of movement so that he could arrange secret meetings with branch leaders, both in person and via secure communications equipment he was given, and providing protection against US drone strikes. Saif al-Adel’s only complaint was a lack of trust between Al-Qaeda jihadists and the Iranian regime, which was closely monitoring his activities, but his close personal relationship with Qassem Soleimani, the IRGC Quds Forces leader killed in a targeted US missile strike in Iraq in 2020, helped smooth over relations with his hosts.

In the first half of 2015, when AQAP had control of the Hadramawt coast in south Yemen, Yemeni figures were able to sail from Mukalla port for meetings with Saif al-Adel in Iran to discuss new operations.[25] A high-ranking figure in the Yemeni branch who participated in one of these trips said Saif al-Adel was trying to find ways of building a network of influence for himself in Yemen despite the resistance of Al-Wuhayshi and his loyal lieutenants.[26] Until Al-Wuhayshi’s death in June 2015, he limited himself to providing advice to the Yemeni leader on how to direct men and cash to Syria and other places.

Saif al-Adel Gets Iranian Funding, Sends Son to Yemen

There were just four months between the release of Saif al-Adel from jail in Iran and the US drone strike that killed Al-Wuhayshi in Mukalla. Abu Baseer’s death was the biggest blow to Al-Qaeda since the killing of Osama bin Laden, but it was a gift to Saif al-Adel.[27] Qassim al-Raymi took over leadership of Al-Qaeda in Yemen during a difficult period of internal crises and external threats but similar backgrounds began to draw Al-Raymi closer to Saif al-Adel. As military officers in the group, both responsible for coordinating external operations and security-related functions.

Al-Wuhayshi had largely embraced the strategic shift made by Al-Zawahiri in 2011 toward placing internal activities that expanded control on the ground on a par with the external activities that were seen as the group’s raison d’etre. But Al-Raymi still leaned more toward focusing on the external enemy, a primary reason he did not hesitate in withdrawing AQAP forces from Mukalla in 2016 or other areas that came under Saudi-led coalition or Houthi control during the conflict. Although Al-Raymi remained loyal to Al-Zawahiri, admiring his ideological vision and respecting his status as Bin Laden’s confidante and successor, he also liked Saif al-Adel’s focus on cleaning Al-Qaeda’s house from within to prevent infiltration, as well as his view that it was the West that should be confronted rather than Iran and its network of proxies in the Arab region.

The first direct communication between the two occurred early in 2016 when Al-Raymi directed Rasheed al-Sanaani, one of his most trusted lieutenants, to take large amounts of cash seized in Mukalla to a remote area on the Iranian coast. Al-Sanaani and four others in his posse met Saif al-Adel there in the presence of IRGC officers.[28]

Al-Sanaani, a lead planner of the attempted assassination of Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Nayef, handed Saif al-Adel the money and received instructions to give similar amounts to the Al-Qaeda branches in Somalia and Syria. Saif al-Adel also described himself during the meeting as the real leader of Al-Qaeda in Syria, and, most importantly, he also charged Al-Sanaani with taking his son back with him to Yemen. To date, the real name of Saif al-Adel’s son remains unknown, though he is known to go by Mohammed al-Hadrami and Ibn al-Madani, among other pseudonyms. But his role in Yemen steadily grew as he became one of the main links between the Al-Qaeda branch in Yemen and his father in Iran, particularly after Qassim al-Raymi and his military officer Ammar al-Sanaani (no relation to Rasheed) were killed in 2020 and 2022, respectively.[29]

Saif al-Adel won the support of the Yemeni branch and used it to increase his direct influence in Syria. When in 2018 Saif al-Adel engineered the creation of a new Al-Qaeda group in Syria called Hurras al-Din (the Guardians of Religion), he established a channel for transferring funds and fighters from Yemen to Syria via Ammar al-Sanaani in Yemen and Abu Bilal al-Sanaani (no relation to Rasheed and Ammar), a Hurras al-Din leader in Syria.[30] Coordination through this channel continued until 2020 when Abu Bilal al-Sanaani was killed in an airstrike in Syria, after which Saif al-Adel used the channel to link Ammar al-Sanaani with another jihadist leader in Hurras al-Din, Abu Hamza al-Yemeni. The two sides continued to communicate until US forces killed Ammar al-Sanaani in a drone strike in March 2022. According to the US military, Abu Hamza al-Yemeni met the same fate three months later.[31]

Saif al-Adel Directs Al-Raymi to Attack the US but Al-Zawahiri Unaware

During 2017 and 2018, Saif al-Adel worked to expand his influence in Yemen by involving himself in the group’s internal arrangements as much as possible. He advised Al-Raymi to give the task of purging spies inside the organization to veteran jihadist Ibrahim Abu Saleh, one of the group of Egyptians who formed the core of Al-Qaeda in Yemen in the late 1990s, along with Al-Zawahiri and Saif al-Adel. Abu Saleh is currently the group’s security officer.[32]

Militarily, Saif al-Adel was keen to ensure the rise of a leadership cadre loyal to him personally, including Ammar al-Sanaani, who became the group’s deputy military officer and later chief military officer. Saif al-Adel favored people who had a more violent approach to leadership positions within the group during the comprehensive restructuring process that Qassim al-Raymi had been conducting since 2017.[33]

In 2019, Saif al-Adel started to show further signs of independence from the Afghanistan leadership, exercising more direct control over Al-Raymi. In December of that year, a Saudi national named Mohammad al-Shahrani conducted a lone wolf attack against US military recruits at the Naval Air Station in Pensacola, Florida. Expecting the Islamic State to announce responsibility, members of the Yemeni branch were surprised to find Al-Raymi claiming the attack as an AQAP operation in a recorded video statement released just days after his death on January 29.[34]

The announcement not only angered the members of the group in Yemen; it was a shock too to the central leadership in Afghanistan, who objected to the lack of coordination over an operation inside US territory. It transpired that Saif al-Adel was the one who organized the operation, without consulting al-Zawahiri, while Al-Qaeda in Yemen had nothing to do with it – despite it being carried out in its name.[35]

The Rise of Batarfi and Saif al-Adel’s Plan for an Attack in Al-Mahra

Appointed as AQAP’s replacement emir for Al-Raymi, Khalid Batarfi had a different relationship with Saif al-Adel, one based far less on a sense of equal footing and similar worldview that governed the relationship between Al-Raymi and Saif al-Adel. Saif al-Adel had played an important role in installing the Saudi national Batarfi as Al-Raymi’s successor over Batarfi’s young rival, the Yemeni AQAP figure Saad al-Awlaqi. Batarfi was also surrounded by a tight network of jihadist leaders who were personally loyal to Saif al-Adel, most importantly Saif al-Adel’s son as well as Ibrahim Abu Saleh and Ammar al-Sanaani (killed in 2022).[36]

Batarfi was also viewed within AQAP itself as a weak leader, lacking the personal charisma and experience of Al-Wuhayshi and Al-Raymi, and this made him more inclined to accept Saif al-Adel’s direction – not least since the organization was reeling from losses in Shabwa, Al-Bayda, and Abyan. A leader in the group describes Batarfi as “a man well-versed in political and religious matters but extremely hesitant to make decisions.” Saif al-Adel supported Batarfi as the new leader precisely because of these weaknesses, hoping to separate the Yemeni leadership from the general leadership in Afghanistan as a precursor to establishing a new stage for jihadist action in Yemen based on prioritizing external operations against Western interests.[37]

Since 2020, Saif al-Adel has been able to convince Batarfi of his strategic approach, focused on confronting Western states and their allies in Yemen – the Saudi-led coalition, the Aden-based government, the United Arab Emirates and its allies – rather than confronting the Iranian-backed Houthi movement. Batarfi was enthusiastic about the idea, and viewed striking Western interests with a well-planned operation as the shortest path to AQAP reclaiming the pioneering role that had won it such credibility within the jihadist movement in the past. Such an operation would also increase Batarfi’s legitimacy as a leader and help him overcome the internal crises that he faced.

In May 2020, media reports said a British ship had been targeted off the coast of Hadramawt.[38] No one formally claimed responsibility for the incident, but a high-ranking figure in AQAP confirmed the group was behind the attack, which had the aim of luring more foreign forces into Al-Mahra and Hadramawt before launching a damaging war of attrition against them.

After the Hadramawt operation, AQAP began training secret cells in Al-Mahra to carry out an attack involving more than 15 suicide bombers. Based on the directives of Saif al-Adel, Batarfi tasked the most qualified field commanders in Yemen with leading the operation: Saleh al-Hadidi and Khaled al-Qusaimi.[39]

At the beginning of October 2020, Al-Hadidi and Al-Qusaimi were busy preparing the operation, which was planned to take place on the first anniversary of Al-Raymi’s death. But local security forces and the Saudi-led coalition launched a surprise security crackdown that included raids on three homes where the jihadists were staying. A number of Al-Qaeda militants were killed and others were captured during the ensuing clashes. In December 2020, the same scenario was repeated in Al-Shihr district on the Hadramawt coast when security forces managed to capture an AQAP cell monitoring international shipping lanes.[40]

This fiasco provoked internal anger over Batarfi’s leadership decisions and the increased interference of Saif al-Adel. When a number of senior figures who had been opposed to the operations contacted Al-Qaeda’s leadership in Afghanistan, they received confirmation that Batarfi had been acting alone without approval from the top.[41] Furthermore, according to a figure close to Al-Zawahiri, the leadership in Afghanistan “completely refused the idea of targeting Western interests in Yemen under existing conditions, since this would have significant negative consequences for the group in Yemen and Sunnis there in general, and would be in the interests of the Houthis.”[42]

Despite the rising internal criticism, Batarfi did not stop providing significant support to Saif al-Adel. In 2021, Batarfi ordered Yunus al-Hadrami, AQAP’s media officer, to travel with two other individuals to the Omani border and then on to Iran with 10 million Saudi riyals for Saif al-Adel. But security forces in Oman captured them and seized the cash.[43]

Part Three: The Repercussions of Saif al-Adel’s Influence

Saif al-Adel Fuels Divisions Within the Group

During Al-Raymi’s time in charge, Al-Qaeda in Yemen faced deep internal disputes. A large number of high-ranking members chose to withdraw from active membership[44] in objection to the group’s policies, while others continued to express dissent without relinquishing their roles. The differences revolved around two issues. The first was Al-Raymi’s use of violence – detaining, torturing, and executing those suspected of acting as moles – to resolve internal disputes and accusations of treason within the group that some felt were made without evidence; the second was the growing role of Saif al-Adel, the Al-Qaeda leader living in Iran while the group’s Yemeni branch was engaged in a war against Iran’s Houthi allies in Yemen.[45]

Al-Raymi’s policy had generally been to de-escalate tensions with internal critics and those who chose to withdraw from active membership by trying to convince them that cooperation with Saif al-Adel only concerned external operations and had nothing to do with their activities inside Yemen. In many cases, Al-Raymi would send Rasheed al-Sanaani and Ammar al-Sanaani to the doubters in an effort to explain the leadership’s view that Saif al-Adel should not be seen as an agent of the Iranians and works – even if under house arrest – to serve the jihadist cause. The two leaders also stressed that Al-Qaeda and Iran share common ground in their hostility towards the United States but that this should not affect Al-Qaeda’s position toward the Houthi movement.[46]

A few leaders who had withdrawn called for Al-Raymi to face internal investigation, but the vast majority of jihadist leaders in Yemen remained loyal to him, although they expressed objections to some of his decisions. This changed considerably with the rise of Batarfi, who lacked the jihadist credentials of Al-Raymi and the domineering ability to keep everyone in line. Second-tier jihadists now began to call for the removal of AQAP’s new emir.

The position of the top-tier leaders of Al-Qaeda in Yemen toward the interventions of Saif Al-Adel have varied, but it is remarkable that none of the jihadist leaders have ever questioned Saif Al-Adel’s competence or loyalty to Al-Qaeda – only opposition to him for strategic or tactical reasons. Some felt that his focus on external operations wasn’t suitable for the Yemeni branch at that time, while other AQAP leaders in Yemen refused to work closely with him on the basis of his presence in Iran. Khabib al-Sudani was one of the senior figures who objected the most to Saif al-Adel’s interference in determining internal AQAP policies, but he did not object in principle to a role in external operations, within limits.[47]

The young AQAP leader Saad al-Awlaqi is known to agree that the first generation of Mujahideen, including Saif al-Adel, have a right to continue to run Al-Qaeda and its various branches. He tried on numerous occasions to bring Batarfi closer to Al-Zawahiri and mend the rift between Al-Zawahiri and Saif al-Adel, though his initiatives failed to overcome the divisions. But despite his respect for Saif al-Adel, Al-Awlaqi believes the Yemeni branch should maintain the autonomy it gained during the time of Al-Wuhayshi as well as keep the group’s focus on fighting the Houthi movement. So while Saif al-Adel can be consulted on AQAP’s external operations and on setting its internal policies, neither he nor Batarfi should take decisions unilaterally, without having reverted to central command in Afghanistan or AQAP’s Shura council.[48]

Ibrahim Abu Saleh, the highest-ranking security officer in the group and a close associate of Batarfi, has avoided publicly engaging in the dispute over Saif al-Adel. He has argued that this is outside the scope of his competencies – which are limited to the internal security aspects – and that decisions on strategic affairs and external operations are the prerogative of Al-Qaeda’s emir in Yemen. But this neutrality works in Saif al-Adel’s favor, and privately Abu Saleh plays a key role influencing Batarfi’s decisions, all of which now align with Saif al-Adel’s directives.[49]

After Al-Zawahiri

Saif al-Adel succeeded in tightening his grip over Al-Qaeda in three stages:

- Increasing his personal influence over regional commanders in Yemen, Somalia, and Syria;

- Creating strong connections between men loyal to him within the leadership of the different branches; and

- Weakening the relationship between these regional branches and the central command in Afghanistan, then completely cutting those links.

Saif al-Adel was of the belief that as soon as Al-Zawahiri left the scene his path to leadership of Al-Qaeda – even if not immediate – would be smooth. While his residence in Iran has protected him from US assassination attempts, it has also placed significant obstacles before his aspiration to lead the group.

Saif al-Adel has repeatedly tried to convince the Iranians that he should move to Yemen. In 2020, he coordinated his operations with the Iranians in Al-Mahra and Hadramawt in an effort to demonstrate the benefit of having him there permanently to launch operations against shared adversaries. But IRGC officials categorically rejected the idea out of fear that Saif al-Adel would find a way to operate independently once he slips outside their control.[50]

Not only that – Saif al-Adel is known to have told a large number of leading AQAP figures that he intends to move the group’s central command to Yemen, with himself either moving to Yemen or leading from Iran as a shadow commander. He has also promised to send leaders from abroad to back Batarfi and help him manage the group.[51]

Until that is achieved, there are three possible scenarios at this stage for the future of Al-Qaeda after the demise of Al-Zawahiri:

- The appointment of a new emir to rival Saif al-Adel, while Saif al-Adel would remain the de facto leader regarding external operations and supervision of Al-Qaeda branches in Syria, Yemen, and Somalia. So far there have not been any nominees with sufficient influence to compete with Saif al-Adel. The sole other candidate is thought to be Al-Zawahiri’s son-in-law Abdelrahman al-Maghrebi, a member of the first generation of jihadists. Al-Maghrebi is currently the external communications officer, running the Al-Sahab Media unit; he is also known to be living in Iran.[52]

- The appointment of a new emir allied to Saif al-Adel who moves the central command out of Afghanistan, perhaps to Yemen. Here, Batarfi is a potential candidate. But due to the internal divisions he faces and the string of losses the local branch in Yemen has suffered in recent years, it seems unlikely Batarfi would be chosen, let alone be in a position to make Yemen a safe haven for Al-Qaeda. Abu Obaidah Ahmad Omar, the leader of Al-Shabaab in Somalia, is being cited internally as a strong candidate to take over. Currently, Al-Shabaab is the strongest branch of them all, controlling significant financial resources and large swaths of territory, and this enables it to establish safe havens for Al-Qaeda leaders. Abu Obaidah has a good relationship with both Saif al-Adel and the senior leadership in Yemen, including Batarfi, and his nomination has been welcomed by AQAP leaders.

- The formal appointment of Saif al-Adel as the new emir of Al-Qaeda. If he were chosen and given allegiance by the various branches while remaining in Iran, the implicit coordination between Tehran and Al-Qaeda would become public and unequivocal, amounting to a strategic alliance along the lines of Iran’s relationship with Sunni groups like Islamic Jihad and Hamas in Gaza. Saif al-Adel’s appointment as Al-Qaeda’s overall leader would likely entail his departure from Iran, either to Yemen, Somalia, or Afghanistan. Until this happens, however, Saif al-Adel will take advantage of the ongoing leadership vacuum to consolidate himself as the de facto leader of Al-Qaeda until conditions are conducive to declaring himself the official leader.

Saif al-Adel and the Future of Al-Qaeda in Yemen

In light of the current political and military situation in Yemen, and the shift of jihadist leadership from Afghanistan to Iran, we can expect two short- and medium-term developments in the behavior of AQAP.

- There will likely be an increased focus inside Yemen on attacking Western interests as well as Saudi-led coalition forces (present in southern and eastern Yemen) and their local allies in the anti-Houthi camp. Throughout 2022, Al-Qaeda’s media promoted a new official position that considers the Presidential Leadership Council (PLC), created under Saudi and UAE auspices in April 2022 to replace former president Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, as their main enemy. The group has also talked in its official statements about the importance of “liberating occupied south Yemen” from “infidel” foreign forces as well as local military and security forces such as those affiliated with the Southern Transitional Council (STC),[53] without addressing the issue of the Houthi movement’s control of most of northern Yemen.

- There will be worsening internal disputes among first-tier members regarding leadership style and the strategic direction that Al-Qaeda should adopt in Yemen. The number of second-tier leaders withdrawing from active membership will likely increase due to the weak leadership of Batarfi, the growing influence of Saif al-Adel, and the shrinking territory under AQAP’s control in Yemen. The situation will become more complicated in the absence of a veteran leader like Al-Zawahiri, whose prestige often enabled him to de-escalate such divisions in the past.

If AQAP goes down the path of attacks against Western, Saudi, and UAE interests in Yemen, it will significantly complicate the current balance of power and present a real threat to UN de-escalation efforts and the fragile stability that has held despite the lapse of the 2022 truce in October, especially in areas under the control of the internationally recognized government. Deepening internal conflicts, on the other hand, could tempt AQAP’s current leadership under Batarfi into an effort to stay relevant and maintain group cohesion through a major attack that would prove disruptive to the delicate political and security situation in the country.

In January, Batarfi met with a number of field commanders, including Abu al-Haija al-Hadidi, Abu Ali al-Disi, Abu Osama al-Diyani, and Abu Muhammad al-Lahji, asking them to prepare teams to carry out car bombings and suicide attacks in Shabwa, Abyan, Hadramawt, and Aden governorates. Batarfi formed a fighters’ mobilization committee headed by Al-Disi, who is in charge of AQAP’s religious and ideological affairs section. Batarfi also directed Al-Hadidi, who is the local emir of Al-Qaeda in Shabwa and Abyan governorates, to mobilize more fighters to carry out operations against the STC’s military and security forces. Although in his last media appearance Batarfi tried to address internal criticisms by lashing out against Iran and the Houthi movement, in recent meetings he has in fact directed AQAP’s field leaders not to carry out any attacks in Houthi-held areas at all.[54]

An increase in Al-Qaeda operations against the anti-Houthi camp could destroy the already weak opportunities for peace in the country. On one hand, it would shift the international focus away from the peace process to counterterrorism activities. Any Al-Qaeda operations that target foreign soldiers in Yemen or strike regional or Western interests outside Yemen’s borders will instantly make fighting AQAP the new and urgent international priority. On the other hand, strikes against the government’s military, political, and economic interests will only further disturb the balance of power and weaken its position vis-à-vis the Houthis. AQAP attacks could also reignite tension between the Islah party and the STC, two major players in the anti-Houthi camp.

The clear involvement of Al-Qaeda in the fighting against Houthi forces in 2015 and 2016 helped feed the international community’s fear of the jihadist group benefiting from the war, prompting the US and its allies to exercise significant pressure on Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and the government to avoid military escalation. Today, the common ground that has emerged between AQAP and the Houthi movement will require increased regional and international pressure on Tehran and its Houthi allies in Yemen to curb their increasing coordination with Al-Qaeda and prevent it from going any further. This, in turn, would require the international community to give up the short-sighted belief that the Houthi movement can be an ally in combating terrorism in Yemen.[55]

Ultimately, the rise of Saif al-Adel has not only shifted the direction of Al-Qaeda’s operations in Yemen; it has impacted the group’s ideological thinking and strategic approach too, bringing it more in alignment with Iranian interests in Yemen and the region. Recent reports suggest that it is not only Houthi forces that Iran is supplying now with weapons – its smuggling networks appear to be funneling arms to Al-Qaeda in Somalia via its Houthi allies in Yemen.[56]

In the long term, the Houthi authorities are likely to benefit from a rise in Sunni jihadist activity in Yemen since it provides a justification for their military expansion under the banner of countering terrorism. Meanwhile, they use Al-Qaeda’s presence in areas outside their control as a cover for unclaimed operations such as the assassination of opponents[57] and targeting of international interests, as has happened in the past, while claiming that these acts are the work of the jihadists. Suspected Houthi attacks on commercial shipping in Al-Mahra and Hadramawt began in December 2020,[58] and the attacks expanded in recent months to include overt targeting of oil terminals, causing significant damage to the government’s finances. Yet Iran and its allies in Yemen were emboldened to pursue this new strategy just months after Al-Qaeda had begun planning similar operations in the same governorates – an initiative that was the brainchild of Saif al-Adel in Iran.[59]

- “Iran-based Egyptian Saif al-Adel is new al Qaeda chief, says US,” AFP, February 16, 2023, https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20230216-us-says-iran-based-egyptian-saif-al-adel-is-new-al-qaeda-chief

- “Iran denies U.S. claims linking Tehran to Al Qaeda’s leader – foreign minister,” Reuters, February 16, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iran-denies-us-claims-linking-tehran-al-qaedas-leader-foreign-minister-2023-02-16/

- Abdel Bari Atwan, After Bin Laden: Al Qaeda, the Next Generation (New York: The New Press, 2012), 80-105.

- Bashir al-Bikr, “Leadership of al-Qaeda in Yemen adn Saudi Arabia: Al-Wuhayshi in Charge [AR],” Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, May 5, 2014, https://www.alaraby.co.uk/قيادات-“القاعدة”-في-اليمن-والسعودية-الوحيشي-رأس-التنظيم1-3

- Atwan, After Bin Laden, 80-105; Abdulilah Haydar, “The History of Al Qaeda in Yemen,” Mareb Press, September 14, 2009, https://marebpress.net/articles.php?id=5804

- Letter from Bin Laden to Al-Wuhayshi, apparently from 2009-2010, in The Abbottabad Documents [AR], issued by Al-Qaeda online publisher Nukhbat al-Fikr, January 2015, p. 108-116 (esp. 110), www.noor-book.com/كتاب-وثائق-ابوت-اباد-كامله-في-ملف-واحد-pdf. The book uses the original documents first published by the US Combating Terrorism Center at West Point military academy, which can be found at the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence web page titled “Bin Laden’s Bookshelf”: https://www.dni.gov/index.php/features/bin-laden-s-bookshelf?start=10a Letter from Bin Laden to Al-Wuhayshi, apparently from 2009-2010, in The Abbottabad Documents [AR], issued by Al-Qaeda online publisher Nukhbat al-Fikr, January 2015, p. 108-116 (esp. 110), www.noor-book.com/كتاب-وثائق-ابوت-اباد-كامله-في-ملف-واحد-pdf. The book uses the original documents first published by the US Combating Terrorism Center at West Point military academy, which can be found at the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence web page titled “Bin Laden’s Bookshelf”: https://www.dni.gov/index.php/features/bin-laden-s-bookshelf?start=10a

- Ibid., pp. 111, 163, 208-9.

- Ibid., p. 5.

- Ibid., p. 270. Bin Laden was proven correct about US intelligence agencies monitoring Anwar al-Awlaqi’s communications; see, “A Danish spy reveals secrets about Al-Qaeda in Yemen and the assassination of Anwar al-Awlaqi [AR],” Al-Masdar, January 14, 2013, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/84931

- Laura Smith-Spark, “What is al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula?” CNN, January 14, 2015, http://edition.cnn.com/2015/01/14/middleeast/yemen-al-qaeda-arabian-peninsula/

- “Yemen’s al-Qaeda: Expanding the Base, International Crisis Group,” International Crisis Group, Feb 2, 2017, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/yemen/174-yemen-s-al-qaeda-expanding-base

- Atwan, After Bin Laden, 80-105.

- Abdelrazzaq al-Jamal, “Al-Qaeda’s Decline in Yemen: An Abandonment of Ideology Amid a Crisis of Leadership,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, September 29, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/15138

- Kyle Orton, “Death and Consequences for Al-Qaeda’s Leadership,” European Eye on Radicalization, November 16, 2020, https://eeradicalization.com/death-and-consequences-for-al-qaedas-leadership/

- From a high-ranking Al-Qaeda source in Yemen, February 2022.

- “Saif al-Adel, the Egyptian Commandos Officer Likely to Take Over Al-Qaeda [AR],” BBC Arabic, August 4, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/arabic/middleeast-62427982. See also: 9/11 Commission Report (US National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, August 2004), p. 251, https://www.9-11commission.gov/report/911Report.pdf

- Kyle Orton, “Al-Qaeda’s Leadership: Deaths and Repercussions [AR],” European Eye on Radicalization, November 22, 2020, https://eeradicalization.com/ar/قيادة-القاعدة-الوفيات-والتداعيات/

- Orton, “Death and Consequences.”

- From a jihadist source in Al-Qaeda in Yemen, February 2022; confirmed by a leader close to the leadership in Afghanistan, March 2022.

- A private letter sent by Saif al-Adl to Khalid Sheikh Mohammed following the US invasion of Afghanistan reveals they were at one point issuing conflicting orders. See “Detention facilities or an operations room? – Did Saif al-Adel direct al-Qaeda from prison in Iran?” Alhurra, October 19, 2022, www.alhurra.com/arabic-and-international/2022/10/19/مرافق-احتجاز-أم-غرف-عمليات-أدار-سيف-العدل-القاعدة-سجون-إيران؟

- Ibid. See Hussam Radman, “Al-Zawahiri’s Death and the End of Bin Laden’s Legacy,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, August 12, 2022, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/july-2022/18402

- Hoda al-Saleh, “This is the story of Bin Laden’s daughter’s escape from Tehran [AR],” Al-Arabiya, November 20, 2017, www.alarabiya.net/iran/2017/11/20/هذه-قصة-هروب-ابنة-أسامة-بن-لادن-من-طهران-

- From a jihadist leader in Al-Qaeda’s Yemen branch, February 2022. See “The Curious Tale of Houthi-AQAP Prisoner Exchanges in Yemen,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, December 17, 2021, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/16002

- From a jihadist leader who was a part of the group that received the released leaders on the Iran-Afghanistan border and who was close to Al-Zawahiri, March 2022. For more details, see “Why did Saif al-Adel refuse to leave Iran? Hassan Abu Haniyeh reveals details,” Akhbar Alan Documentaries, August 13, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AOa1sZe5jKc&t=197s

- From a jihadist leader in Al-Qaeda’s Yemen branch, February 2022.

- Ibid.

- Some of the jihadist leaders who withdrew from active participation in the group and strongly objected to Saif al-Adel’s policies have accused him openly of being involved in Al-Wuhayshi’s killing, after Saif al-Adel was previously accused of having killed high-ranking members that he did not approve of.

- From a jihadist leader in Al-Qaeda’s Yemen branch, February 2022.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. Also confirmed by a Yemeni security source. For more information on the relationship between Saif al-Adel and Hurras al-Din in Syria, see Abdelghani Mazouz, “Guardians of Religion: Problems of Its Creation and Its Dismantlement [AR],” Egyptian Institute for Studies, September 10, 2022, www.eipss-eg.org/تنظيم-حراس-الدين-إشكاليات-النشأة-والتفكيك/#_ftnref26

- Amin al-Asi, “Hurras al-Din in the US line of fire [AR],” Al-Araby al-Jadid, June 29, 2022, .alaraby.co.uk/politics/”حراس-الدين”-في-دائرة-الاستهداف-الأميركي

- Muayyid Bajiss, “Al-Qaeda in Yemen Issues Biography of its most Prominent Current Leaders [AR],” Arabi21, December 9, 2015, https://arabi21.com/story/877603/قاعدة-اليمن-تنشر-السيرة-الذاتية-لأبرز-قادتها-الحاليين

- Information from a leader in AQAP, February 2022, and confirmed in July 2022 by a jihadist who withdrew from active membership in the group.

- Information from a leader in AQAP, February 2022. See Samy Magdy, “Al-Qaida in Yemen claims deadly Florida naval base shooting,” Associated Press, February 2, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-shootings-yemen-ap-top-news-pensacola-69a7bfc8d72823a1d055c73bbb349177

- Information from a jihadist leader close to Al-Zawahiri, March 2022; confirmed by another jihadi leader in Yemen in February 2022.

- From a jihadist leader who withdrew from active membership in AQAP, July 2022.

- Ibid.

- “British Ship Targeted Off the Coast of Hadramawt [AR],” Yemeni News, May 17, 2020, https://sa24.co/show13346662.html

- From a Yemeni leader in Al-Qaeda, February 2022; confirmed by Yemeni security sources.

- Ibid.

- From a jihadist leader who withdrew from AQAP, July 2022; confirmed by a current leader in Al-Qaeda’s Yemen branch.

- From a non-Yemeni jihadist leader who was close to Al-Zawahiri, March 2022. Houthi forces were advancing at the time in Marib and Shabwa.

- From a jihadist leader who withdrew from AQAP, July 2022; the information was confirmed by a non-Yemeni leader close to the central Al-Qaeda leadership in Afghanistan.

- This term is used to denote the middle ground between completely defecting from the group and taking a position of open opposition within the group. The member quits the functions they had been tasked with and returns home, without renouncing the organization or its aims. They may return to active membership if the issue in dispute is resolved. The first members to withdraw in this manner was the group loyal to Abu Omar al-Nahdi, the former emir of Mukalla, after which it became quite common.

- Information from a jihadist leader in AQAP who withdrew from active membership in 2021, July 2022.

- Ibid.

- This information was provided by a senior figure in AQAP, February 2022, and another senior figure who has withdrawn from active participation in AQAP, July 2022.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- From a prominent leader in AQAP’s Shura Council, August 2022.

- Ibid.

- “Abdulrahman al-Maghrebi: Brief Profile,” Rewards for Justice, rewardsforjustice.net/ar/rewards/عبد-الرحمن-المغربي-abd-al-rahman-al-maghrebi/

- Asem Taha al-Sabri, “Al-Qaeda Reorganizes Priorities in Yemen: Exclusive Details About Abu Ali al-Hadrami [AR],” Akharb al-Aan, August 28, 2022, https://www.akhbaralaan.net/news/arab-world/2022/08/28/تنظيم-القاعدة-يعيد-ترتيب-أولوياته-في-اليمن-وتفاصيل-حص رية-عن-القيادي-في-التنظيم-أبو-علي-الحضرمي

- Assim Taha al-Sabri,“A preemptive plan for the leader of Al-Qaeda in Yemen to strike liberated governorates with explosives [AR],” Akbar Alan, January 28, 2023, www.akhbaralaan.net/news/special-reports/2023/01/28/خطة-استباقية-لزعيم-القاعدة-في-اليمن-لضرب-المحافظات-المحررة-بالمفخخات

- The rise of the Houthi movement was an important factor in creating the conditions for the spread of extremism in that it contributed to sectarian polarization and the weakening of state institutions. With Al-Qaeda currently weakened in areas under government control, the Houthis appear to have allowed the jihadists some freedom of maneuver that gives Al-Qaeda the opportunity to target their common enemies.

- “Seizure of Weapons Shipment Smuggled from Yemen to Somalia [AR],” Aden al-Ghad, July 4, 2022, https://adengad.net/public/posts/625367; Jay Bahadur, “An Iranian Fingerprint? Tracing Type 56-1 Assault Rifles in Somalia,” Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, November 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/GITOC-An-Iranian-Fingerprint-Tracing-Type-56-1-assault-rifles-in-Somalia.pdf; Michael Segal, “The IRGC helps smuggle weapons to the Shabaab movement in Somalia [HE],” The Jerusalem Center for Public and State Affairs, July 6, 2022, www.jcpa.org.il/article/חיל-הים-של-משמרות-המהפכה-מסייעים-בהבר/

- For example, in 2021 anti-Houthi figure Musa Al-Mashdali was assassinated in northern Aden governorate days before the Houthis took control of his home governorate, Al-Bayda. In that same year, there was a failed assassination attempt against the governor of Aden, Hamid Lamlas. In 2022, southern military commander Thabet Jawas, the military leader thought to have been behind the killing of Houthi movement founder Hussein al-Houthi during the Sa’ada wars in the early 2000s, was assassinated. Based on its investigations, the government believes the Houthis were behind these incidents, despite the fact that rising Al-Qaeda activity at the time caused the media to assume that Al-Qaeda was responsible.

- “Return to Targeting Ships: The Most Prominent Attacks in the Red Sea, the Gulf, the Arab Ocean, and Gulf of Oman [AR],” Al Jazeera.net, December 14, 2020, www.aljazeera.net/politics/2020/12/14/عودة-استهداف-الناقلات-أبرز-الهجمات-في

- The first drone attack was in December 2020, when a British ship was targeted in A-Mahra, several months after a similar attack by Al-Qaeda in Hadramawt. This pattern of operations continued until it reached a peak in late 2022 when the Houthis openly adopted it as a bargaining chip in its economic warfare with the government. In other words, the Houthis are using Al-Qaeda today in two ways: as a cover for some security operations of its own and as a means of testing the reactions of its adversaries before adopting new forms of operation, which have now changed the nature of the conflict.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية