Executive Summary

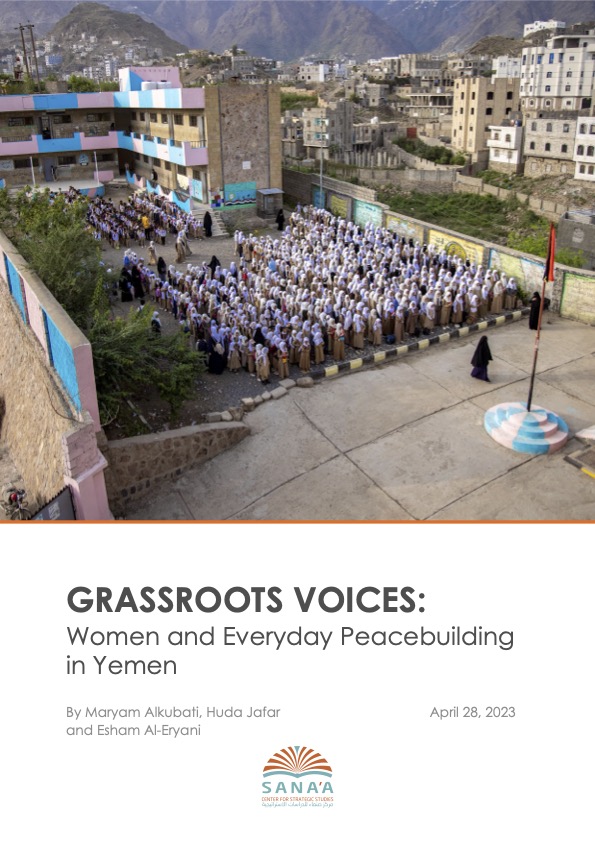

Over eight years of war in Yemen have had dire consequences on people’s day-to-day lives and shaped their definitions and perceptions of peace. Years of failed negotiations have allowed the warring factions to monopolize conversations on peace. Within these negotiations, women at both the local and national level have been largely excluded, despite them being at the forefront of mitigating the war’s impact on Yemenis. Utilizing a community-centered approach, this study seeks to give agency to Yemenis to define peace based on their own lived experiences, propose practices that promote women’s role in peacebuilding, and suggest ways to mitigate local practices that produce or reproduce gender inequalities and violent or non-peaceful practices. The study heavily draws on feminist literature that argues the ‘hidden’ everyday practices carried out by women — procreation, day-to-day routines, caregiving, satisfying basic human needs, negotiating inequalities, social relations, and resolving conflict—are integral to social cohesion, but inadequately researched nor recognized.

One hundred twenty-eight Yemeni women and men from different age groups, geographical areas, and socio-economic backgrounds took part in this research. Focus group discussions were held in the governorates of Sana’a, Ibb, Aden, and Hadramawt between January and March 2022. Across the governorates, interviews were also carried out with various decision-makers, community leaders, imams, and religious leaders. The study does not aim to give a representative overview of the experiences of all women in Yemen, given its diversity and the limitations of conducting fieldwork in the country. Instead, it utilizes a micro-level approach to amplify local voices and agency. Allowing Yemenis to use a familiar language, identify their needs and priorities while also utilizing peace practices from their daily lives, creates enabling environments for women to participate in peacebuilding, and enhances larger peace intervention mechanisms. Furthermore, defining peace and the Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda from the perspectives of local actors and grassroots women shifts the focus from a Western-centric approach toward a Yemeni-centric one. Below is a summary of the findings that emerged from the focus group discussions and interviews.

Yemenis’ definitions of peace are similar, with some regional differences. Across the four governorates, participants’ definitions of peace mainly centered around security and stability, freedom of mobility and speech, meeting basic needs, coexistence embedded in Islamic faith, and peace as dignity. Women and men had similar definitions of peace. However, among participants from Sana’a governorate, where restrictive measures on social conduct and mobility under the Houthi authorities have become more prevalent, peace as freedom of expression and movement was more prominently voiced than in other governorates. In Aden, more pronounced was the desire for “peaceful coexistence and the rejection of racism and sectarianism.”

Women’s role in peacebuilding is widely recognized, but many associate it with the private sphere. Regardless of their gender, background, or geographical location, participants consulted throughout the course of this research agreed that women play a critical role in peacebuilding. The majority, however, associated this role within the confines of the private sphere (the home), primarily as mothers (revered as society’s primary peacebuilders, responsible for raising peaceful generations, and maintaining social cohesion) or in realms deemed as extensions of the private sphere (i.e., schools, mosques, and female gatherings).

Female peace activists face social stigma from both women and men. The focus group discussions revealed that women publicly active in the field of peacebuilding in Yemen face social stigma, a perception held by both men and women, with some women stating that female peace activists did not necessarily represent them. Harassment of female peace activists in both Houthi-controlled territories and those under the internationally recognized government were widely reported, with defamation campaigns cited as the prime obstacle hindering women from engaging more publicly in peacebuilding.

Peacebuilding work is viewed by many as a ‘Western concept’. Terms like ‘peace’ or ‘peacebuilding’ and ‘gender equality’ are perceived as Western concepts among some segments of Yemeni society, which inevitably hinders the work of people and organizations, and women in particular, who were perceived by some as ‘naively’ accepting Western concepts dictated by local and international organizations. Many respondents were skeptical of international organizations that call for the promotion of peace. Officials and community leaders interviewed in Houthi-held Sana’a and Ibb completely rejected the role of international organizations in spreading peace on the ground. In Hadramawt and Aden, mosque preachers and religious figures were also distrusting of the international organizations, although they were open to supporting them if their work aligns with the principles of Islam and Islamic rulings.

Day-to-day survival mechanisms employed by Yemeni women are integral to social cohesion. In their daily lives, women were found to negotiate inequalities, mediate family and community conflict, navigate insecurity, and practice daily resistance and resilience. This was largely done within private spaces (homes, neighborhoods, mosques, schools) more so than public ones (political platforms) predominantly occupied by men. At the grassroots level, respondents cited many examples of women mediating conflict and noted a tradition of conflict resolution embedded in Yemeni culture, which views women as catalysts for peace when conflict arises.

Religious discourse that both empowers and incites. Many women cited restrictions on travel, notably the need for a male guardian (mahram), the need to maintain segregation, the impossibility of spending late hours at work, the innate skepticism of women working in the promotion of peace, the misleading religious discourse by some sheikhs, and the weak support provided by the family as just some of the restrictions imposed on women. Often, these are based on extremist and conservative interpretations of Islam. While misconstrued interpretations of Islam were said to oppress women, many women felt that when channeled in the right direction, religious discourse was empowering. Female Islamic preachers (daiya)[1] in Yemen, for instance, were viewed as important actors in empowering women through religious arguments, equipping them with strong foundations in Islamic law to be able to counter extremist narratives.

Full recommendations are offered at the end of this report and serve as a guide for both domestic and international stakeholders to promote a more inclusive and bottom-up approach to peacebuilding and encourage better integration of women’s daily peacebuilding practices in larger peace frameworks. Specifically targeting the international community, the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen (OSESGY) and local actors working in the field of peacebuilding and gender equality these include:

- Recognize human security as an integral component of peacebuilding efforts.

- Empower grassroots women in Yemen by recognizing their everyday practices in peacebuilding.

- Engage men as partners and advocates for female peacebuilders.

- Localize peacebuilding initiatives by building on Yemenis’ definitions of peace and approaches to peacebuilding.

- Enforce laws that protect peace activists in Yemen.

- Collaborate with local and national organizations to raise awareness on peace projects and peacebuilding work on the ground with the goal of building trust with local communities who are increasingly skeptical of peacebuilding work.

- Engage religious and community leaders in women’s empowerment for peace.

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية

اقرأ المحتوى باللغة العربية